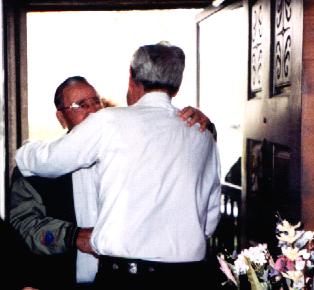

In the top

picture, you are seeing Ivy Stafford (age 80) and Miles Stephens (age 78) greeting one

another after 54 years. The last time they had seen one another was in a foxhole 500

yards from the enemy lines in Hurtgen Forest two weeks prior to the bloodiest land battle

in World War II ... the Battle of the Bulge. Ivy Stafford (my Father) is on the

right in the second picture and Miles Stephens is on the left. I didn't think we'd

ever get them to sit down as both were extremely excited to see one another. The

following is their story as told by reporter, Melody Overton, of the Victoria Advocate

newspaper.

Both men went to

war in 1944 and found themselves stationed in the heavily wooded plateau of Ardennes 12

miles from Luxembourg in the distance. Hitler had planned to launch an offensive

between Nov. 20-30. He was confident the Allies wouldn't be able to react in time to

stop the offensive.

Around December 1

at night, a 28-year old Stafford took his turn guarding the foxhole.

"I was

sitting on my ankle at the mouth of the hole and things were quite," he said.

"All of a sudden, an artillery shell hit a tree overhead. It split my helmet,

went through my jacket, busting the zipper out, went in my left thigh and through the

other side, finally hitting my M-1 carbine, tearing it up."

While Stafford

applied a tourniquet and sulphadiazine powder to his wound to stop the bleeding, Stephens,

26, suffered a shrapnel wound to his back.

Stafford waited

for 24 hours in the foxhole unable to fight and lost a large amount of blood. Found

by another GI, he was taken by jeep to a Belgium hospital, where he was operated on, then

onto Oxford, England to recover.

"You could've

fit a Coca-Cola bottle through the hole in my leg. The surgeons had stuffed a rag

through the hole to where you could see both ends sticking out of my leg. I don't

know why they did that before they sewed me up," Stafford said.

While Stafford was

taken away, Stephens remained, ready for combat despite his wound.

During a big push

toward the enemy lines, Stephens was hit by a sniper's bullet in the chest area.

Luckily, the bullet hit a can of potted meat in his right pocket, ricocheted, and went

into his right biceps.

"I came up

with a handful of blood. I didn't realize what had happened. I knew I was

alive and I decided to move on," Stephens said. He said his first wound hurt more

than the second. "The shrapnel was worse than the shot. That shrapnel burns and

lights you up," he said.

He too was sent to

England to recover. Both men received their medical discharges in 1945.

While Stafford and

Stephens recuperated, 30 German divisions roared across an 85-mile Allied front from

southern Belgium to the middle of Luxembourg on December 16, 1944. By Christmas, the

German offensive had opened a bulge 50 miles into the Allied lines, forcing the biggest

mass surrender of American soldiers since Bataan (note of interest: my father-in-law is a

survivor of the Bataan Death March), some 4000 men in a single day.

American troops

never gave up. On January 8, Hitler ordered his troops to withdraw from the tip of the

Bulge. By Jan. 16, the Third and First Army had joined at Houffalize. The Allies now

controlled the original front. On Jan. 23, Saint Vith was retaken. Finally, on Jan. 28,

the battle was over.

"Hitler got

mad that day," Stafford said. "He (Hitler) was a nut if there ever was

one," Stephens quickly replied.

Stafford said he

wished they would've gone across the Rhine away from the wooded area because every time a

shell fired, it splintered the trees into the foxholes. "That forest looked like a

bunch of toothpicks," he said.

The two men said

they didn't have time to talk much after digging foxholes, cutting trees to cover them and

trying to stay warm. They mentioned getting out alive to each other but most of the time

they prayed.

"One soldier

said to me, 'I don't know how to pray' and I said, 'You better learn'," Stephens

said. "I told myself I was coming back. I didn't let myself think of dying."

Stephens said he

didn't let the mayhem that occurred cloud his judgment. "You couldn't stop and feel

for the others dying around you. You had to think about yourself to survive."

He always knew the

Germans would lose. "I didn't have any use for them Germans. They interrupted my life

keeping me way from wife and kids. I wanted to get it over with."

The soldiers stole

rations and money from the deceased German troops but they never took rings off the

frozen, dead fingers of a soldier or pictures of Hitler in case of booby traps. They

didn't trust the Hitler youth, either.

Even though they

received free cigarettes and tea, they couldn't light a smoke or a fire to boil water

without being shot at. Hot meals consisted of orange marmalade, peanut butter and black

coffee. The cold and snow was the worst of all.

"In the

combat field, we just had blankets to keep warm in the holes. My feet were almost frozen

when I was shot," Stafford said. "If I wouldn't have gone to a hospital when I

did, I would've lost my feet."

In the years

following the war, Stafford became a farmer in Elsa, Texas before moving to Victoria,

Texas. He said on certain cold days, he would be flooded with memories. Stephens retired to

Lutcher, Louisiana after owning a paint business in California. Both men had one child

going into the war and after the war, each had a daughter they both named, ironically,

Linda.

Both of the men's

wounds left scars. Stafford's knee gives him trouble once in awhile and Stephens suffers

from back pain and nerve damage in his left arm.

Miles Stephens gently touches

the hand

of his long, lost friend from WWII,

Ivy Stafford. The two men looked over old

photos and caught up on the 54 years they were apart.

(For Reunion Photo Album)