Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields:

California: Western Los Angeles Area

© 2002, © 2016 by Paul Freeman. Revised 11/19/16.

This site covers airfields in all 50 states: Click here for the site's main menu.

____________________________________________________

Please consider a financial contribution to support the continued growth & operation of this site.

Baker Airport / Culver City Airport (revised 10/28/16) - Brown Ranch Airfield (revised 10/10/12) - Burdette Airport / Dycer Airport (revised 3/13/16)

Dycer Airport / Universal Airport / Gotch's Airport / Western Avenue Airport / Gardena Valley Airport (revised 10/28/16)

Gardena Airport (revised 6/3/11) - Goodyear Airship Factory (revised 2/6/16) - Hughes Airport (revised 10/28/16)

Los Angeles Motordrome (revised 11/19/16) - Rogers Airport (revised 10/3/16) - Santa Monica Island Airport (added 6/4/16)

____________________________________________________

Santa Monica Island Airport, Santa Monica, CA

33.942, -118.539 (West of Los Angeles, CA)

showing the hinged nose of a never-built U.S. SST at top-right.

This is an example of an airport which was planned but abandoned before ever being built.

During the 1960s, plans for the U.S. Supersonic Transport (SST) caused many city planners to wonder whether runway lengths of existing major airports would be sufficient for the new SSTs,

in addition to the whether surrounding communities would be able to tolerate the noise generated by the expected large-scale operation of SSTs.

In Los Angeles, these factors caused an effort to plan to build a completely new island off the Pacific coast of Los Angeles,

immediately off shore of the existing Los Angeles International Airport.

The caption of a 3/12/68 artist's conception by Donald Jaye read:

“Drawing of a combined Los Angeles International Airport.

Drawing shows a new Santa Monica Island with a subway connecting to the airports (bottom) & a causeway, bridges & subway at the top of drawing.

The island will have provisions for the SST, with two 15,000' runways.

The island will also have its own commercial area, hotels, art center, trade center & office building, apartments, parks & beaches, an aerospace university & a sports center.”

showing it to have two 15,000' parallel runways on the south side of the island,

with a subway connection extending to the east to the existing Los Angeles International Airport.

The U.S. SST program was canceled in 1971, presumably ending any effort on the never-built Santa Monica Island & its airport.

Thanks to Kevin Walsh for pointing out this facility.

____________________________________________________

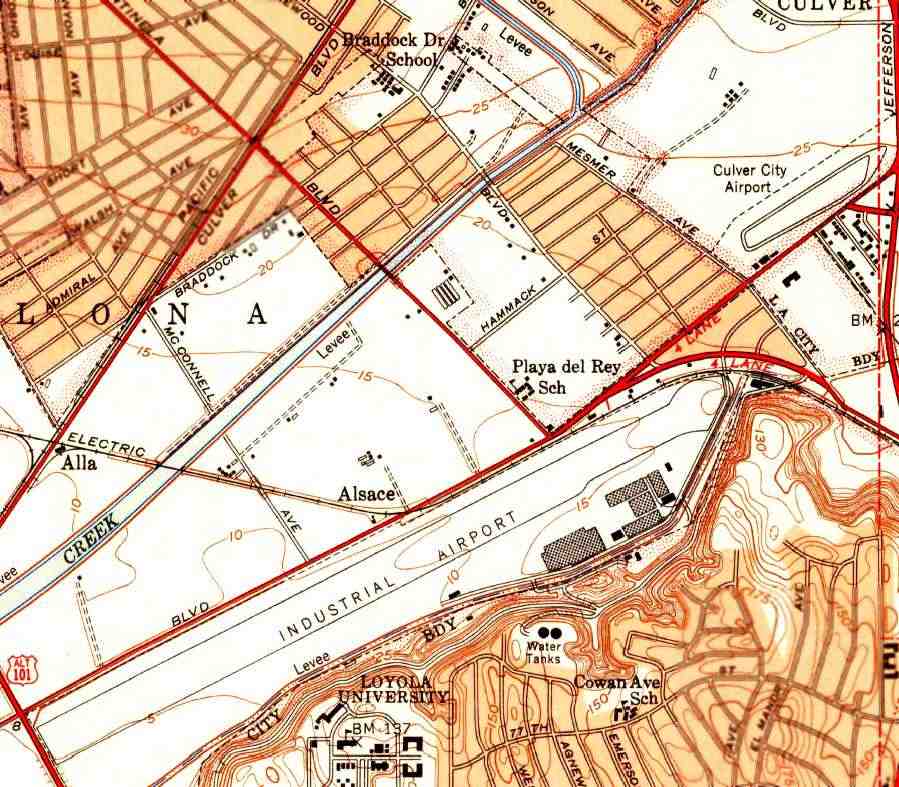

Los Angeles Motordrome, Playa Del Rey, CA

33.966, -118.444 (Northwest of Los Angeles, CA)

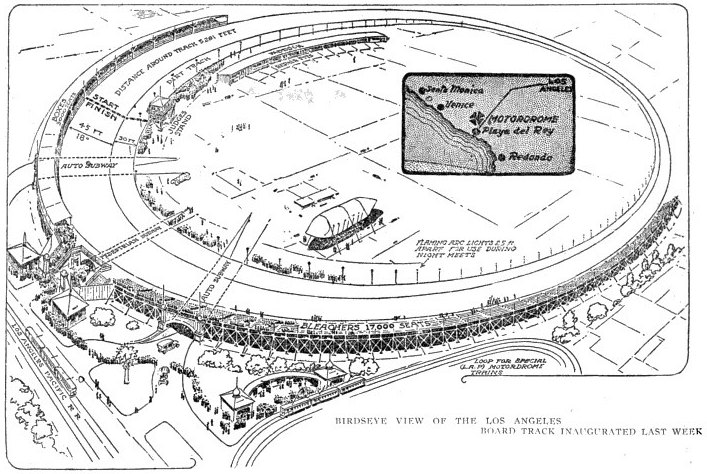

A 1910 artist's conception of the LA Motordrome.

The Los Angeles Motordrome was a circular 1-mile wood board automobile race track.

Construction began on 1/31/10.

Seating was provided for 40,000 spectators, including a covered grandstand built to hold 12,000.

The opening event at the Motordrome was a 9-day series of races & exhibitions beginning 4/8/10.

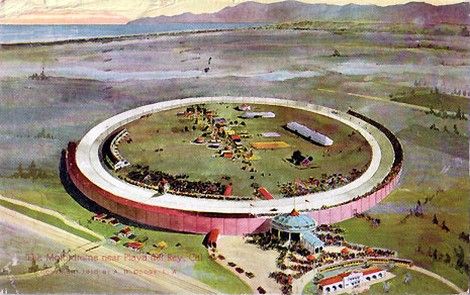

A circa 1910 postcard image of the LA Motordrome.

Plans to include aviation uses were made early on, with track founder Frederick Moskovics inviting the Aero Club of America

and aircraft manufacturers, including the Wright Brothers & Glenn Curtiss, to make use of the Motordrome's facility for experimentation & exhibition.

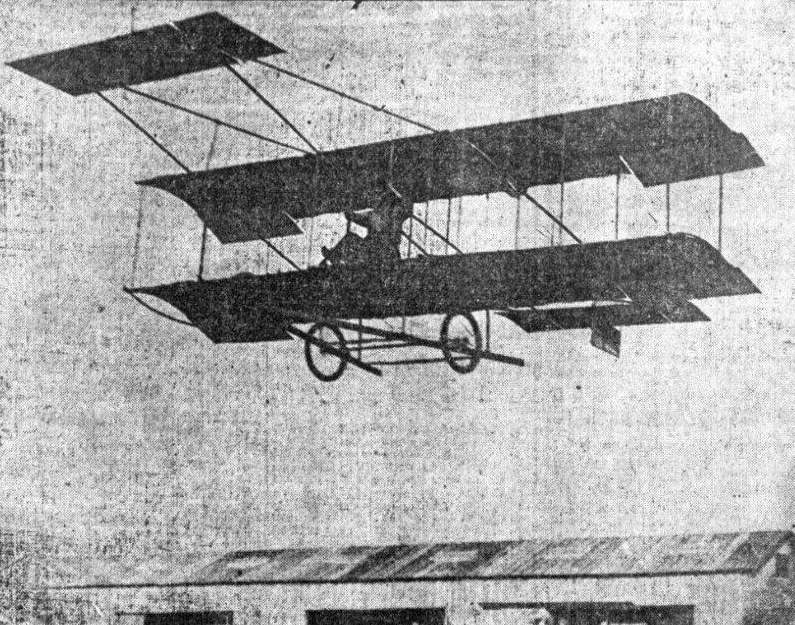

A 1910 photo of the hangar constructed by The Aero Club of California at the Motordrome, large enough to hold 16 aircraft.

A 1910 photo of a glider piloted by Jack Cannon being towed aloft by an automobile at the Motordrome.

An advertisement for the 10/22/10 “Senational Aviation Meet” at the LA Motordrome.

Later in 1910, aviation pioneer Glen Curtiss moved to California from NY & set up a shop & a flight school at the Motordrome,

and used the facility for seaplane experiments for a time before moving that work to San Diego.

On 8/11/13, a fire blamed on vagrants burned part of the Motordrome's race track.

Though the facility was not fully destroyed, the owners elected not to rebuild it,

in part because the trolley line which served the track had outlived its useful life.

The last depiction which has been located of the LA Motordrome was on the 1930 USGS topo map.

Curiously the 1930 topo still labeled the site of the Motordrome, but the building itself was no longer depicted,

evidently since it had burned down 17 years before.

In a 1937 aerial view looking east (courtesy of Kevin Walsh), the trace of the LA Motordrome was still recognizable as a light-colored circular feature to the right of the channel,

with oil derricks in the immediate background.

A 1952 aerial view showed a faint trace still remaining of the Motordrome's circular layout.

A 2016 aerial view showed a faint trace still remaining of the Motordrome's circular layout,

with the property remaining unredeveloped more than a century after the Motordrome burned down.

The site of the LA Motordrome is located at the intersection of Culver Boulevard & Jefferson Boulevard,

only a half-mile west of a much more famous airfield, that belonging to Howard Hughes.

Thanks to Greg Mosholder for pointing out this facility.

____________________________________________________

Brown Ranch Airfield, Calabasas, CA

34.104, -118.704 (Northwest of Los Angeles, CA)

An undated (circa 1940s/50s?) aerial view looking east at the Brown Ranch Airfield (courtesy of John Hazlet),

showing some very challenging terrain directly off the runway end.

In 1926, razor baron King Camp Gillette commissioned Wallace Neff to build him a "paradise on earth" in Southern California.

The result was a stunning 25 room mansion built in the Spanish Colonial Revival Style whose beauty supposedly brought Gillette to tears.

Gillette died in 1932, and his widow sold the property to prominent film director Clarence Brown in 1935.

Brown regularly hosted large parties for well-known Hollywood personalities here,

and made several changes to the property including the addition of a small airfield with a single northwest/southeast runway to the east of the main house.

According to a CA State map, the airfield was “installed by Brown circa 1938.”

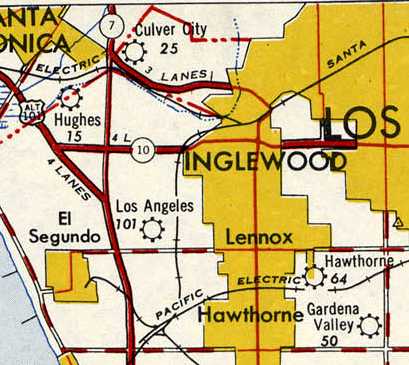

The Brown Ranch Airfield was not depicted on the 1939 or 1944 LA Sectional Aeronautical Charts,

nor on USGS topo maps from 1944 or 1947.

The earliest depictions which have been located of the Brown Ranch Airfield were several undated (circa 1940s/50s?) aerial views

looking along the runway at Brown Ranch (courtesy of John Hazlet).

An undated (circa 1940s/50s?) photo (courtesy of John Hazlet) originally captioned, “"Clarence Brown's Plane in Front of Hangar."

John Hazlet observed, “The adjacent terrain looks like it could be Gillette Ranch; it looks like a very early Beech 35 Bonanza with a composite propeller.”

The earliest dated depiction of the airstrip at Brown Ranch was on the 1950 USGS topo map,

which depicted a single 2,100' paved northwest/southeast runway, with circular turn-around pads at both ends, labeled “Aitstrip”,

adjacent to the east side of the Brown Ranch.

A 1952 aerial photo depicted the Brown Ranch Airfield as a single northwest/southeast runway (possibly paved)1950 USGS topo map,

which depicted a single 2,100' paved northwest/southeast runway, with circular turn-around pads at both ends,

adjacent to the east side of the Brown Ranch.

A single small building (possibly the hangar) was adjacent to the north side of the west end of the runway.

Brown sold the property to the Claretian Order of the Catholic Church in 1952, which used it as a seminary & noviate,

presumably putting to an end the use of the property's airfield after a brief 14-year run.

A CA State map depicted “Gillette Ranch Historic Conditions 1954” depicted the “Airstrip installed by Brown circa 1938.”

A 1959 aerial view still showed the recognizable trace of the runway, but it appeared deteriorated compared to the 1952 photo,

and the presumed hangar had been removed at some point between 1952-59.

The Brown Ranch Airfield continued to be depicted on the 1967 USGS topo map,

but was no longer depicted on the 1968 USGS topo map.

A 1977 aerial view showed no remaining trace of the runway,

with the area now an indistinguishable grass lawn, and a pair of tennis courts having been built over the center of the former runway.

The Claretians subsequently sold the ranch property to Elizabeth Clair Prophet's Church Universal & Triumphant in 1977,

which in turn sold to the Soka University of American in 1986.

In 2007, Soka sold the property to the National Park Service.

The 588-acre King Gillette Ranch opened to the public as a park on 6/30/07.

A 5/25/09 aerial view showed no trace remaining of the former Brown Ranch Airfield.

A 10/8/12 photo by John Hazlet of the site of the Brown Ranch Airfield.

John reported the photo is “looking approximately east from the west end of the location of the former airstrip.

No trace remains of the runway or the pad upon which the hangar sat.”

The site of Brown Ranch Airfield is located southeast of the intersection of Mulholland Highway & Las Virgenes Road.

Thanks to John Hazlet for pointing out this airfield.

____________________________________________________

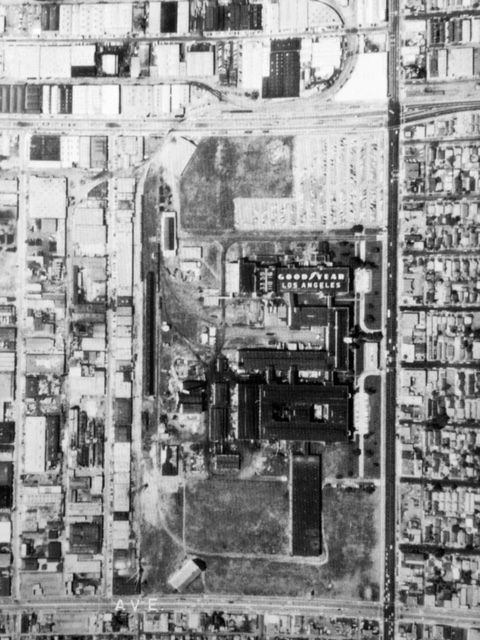

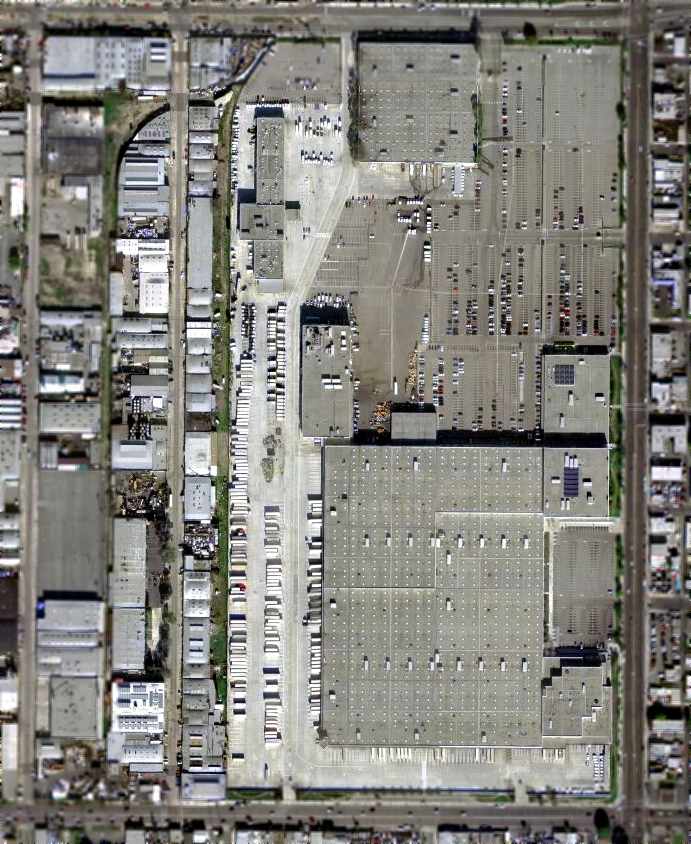

Goodyear Airship Factory, Huntington Park, CA

33.979, -118.259 (East of Los Angeles International Airport, CA)

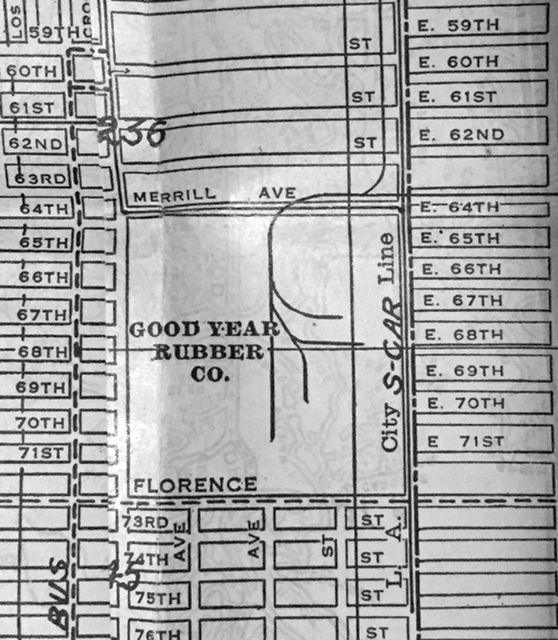

The “Good Year Rubber Co.”, as depicted on a 1930 street guide (courtesy of Kevin Walsh).

This facility within Los Angeles was a large manufacturing complex where the Goodyear company manufactured airships (blimps).

The date of establishment of the Goodyear facility has not been determined.

The earliest depiction which has been located of the Goodyear facility was on a 1930 street guide (courtesy of Kevin Walsh).

It depicted the “Good Year Rubber Co.” as a square block with several rail lines, but it did not depict any buildings.

The earliest topo map depiction which has been located of the Goodyear facility was on the 1937 USGS topo map.

It depicted several large factory buildings in the center of the property,

with open areas (airship fields) on the north & south sides, on the west side of which were several hangars.

A 1940 Shell street map (courtesy of Gary Alexander) labeled airport #14 on the map as “Goodyear Airship Base”.

According to Charles Irvin, “The main building faced Central Avenue,

and from what I can recall from my childhood, the only hangars I knew of

were the ones at the northwest / southwest corners of the plant (the angled buildings).

The southwest one had 'Goodyear' painted across the rooftop along with the winged shoe logo,

and was visible (the rooftop & logo) from the Harbor Freeway that runs west of the plant.

I can remember the one hangar, I can remember the administration building.

The main manufacturing building was massive, and pretty much all the buildings were concrete

except for the hangars, which I think were sheet metal - but again, huge.”

A 12/4/52 aerial photo flown by Fairchild Aerial Surveys (courtesy of Robert Pope),

showed the Goodyear Airship factory complex & what appeared to be at least 4 blimp hangars, on the north & south sides of the complex.

One large building had “Goodyear Los Angeles” painted on the roof.

The date of at which airship operations came to an end at the L.A. facility has not been determined.

It was subsequently reused by Goodyear for tire manufacturing.

A 1980 aerial view showed that the former Goodyear Airship plant was not much changed compared to as seen in 1952,

with the hangars still standing on the northwest & southwest corners of the property,

and “Goodyear Los Angeles” still painted on the roof of one large building.

According to Charles Irvin, “There was a LOT of 'bad blood' over this plant:

it had become a tire re-capping plant in later years,

and operations were moved out of state in an attempt to help clean up the air in L.A.

When it was time to demolish buildings, several groups tried to get at least one hangar listed as a historical building / national landmark,

and all attempts failed - Goodyear wanted nothing to do with the place anymore,

and refused to help (seems they were forced out of L.A. against their will, and were/are still very bitter over it).”

Amazingly a 1983 aerial view (courtesy of Kevin Walsh) showed that the former Goodyear Airship plant was not much changed compared to as seen in 1952,

with the hangars still standing on the northwest & southwest corners of the property,

and “Goodyear Los Angeles” still painted on the roof of one large building.

Ironically, the former Goodyear airship factory had some aviation reuse long after it was abandoned.

According to Charles Irvin, “If you look at the film 'Blue Thunder' [1983],

a good portion of the end of the film was shot at the old plant:

it's the chase scene with Schieder & McDowell & their respective helicopters,

and they shoot up the plant pretty good (you can tell in the film that it had been abandoned for quite some time).

But - they stayed away from the hangar (only the southwest hangar remained until the plant was demolished).”

The 1994 USGS aerial photo showed that the site of the former Goodyear airship factory had been covered by a large new building

(the Central Los Angeles Post Office) at some point between 1980-94,

and it did not appear as if any remnants of the Goodyear complex had survived.

As seen in the 2004 USGS aerial photo, the former Goodyear airship factory & hangars were replaced by the Post Office building, leaving no trace of them.

However, the row of smaller buildings along the west side of the property (visible in the 1952 photo) still remain intact.

Charles Irvin reported in 2007 that he went to Goodyear's Airship Operations in Carson

to look for photographs of the Goodyear Los Angeles airship factory,

“Only to find they had none at all, except for a close-up of a prototype blimp:

the photo was taken from the doorway of the south hangar,

looking towards the main administration / production building (it was a huge concrete building).

Goodyear's corporate offices also do not have any photographs of the plant,

nor was the late Hal Fishman of KTLA News (a record-holding pilot who had covered L.A. most of his life)

able to find anything in their archives about it - seems everybody wanted to forget that it ever existed.”

The site of the Goodyear factory was bounded by Florence Avenue on the south,

Central Avenue on the east, Gage Avenue on the north, and McKinley Avenue on the west.

____________________________________________________

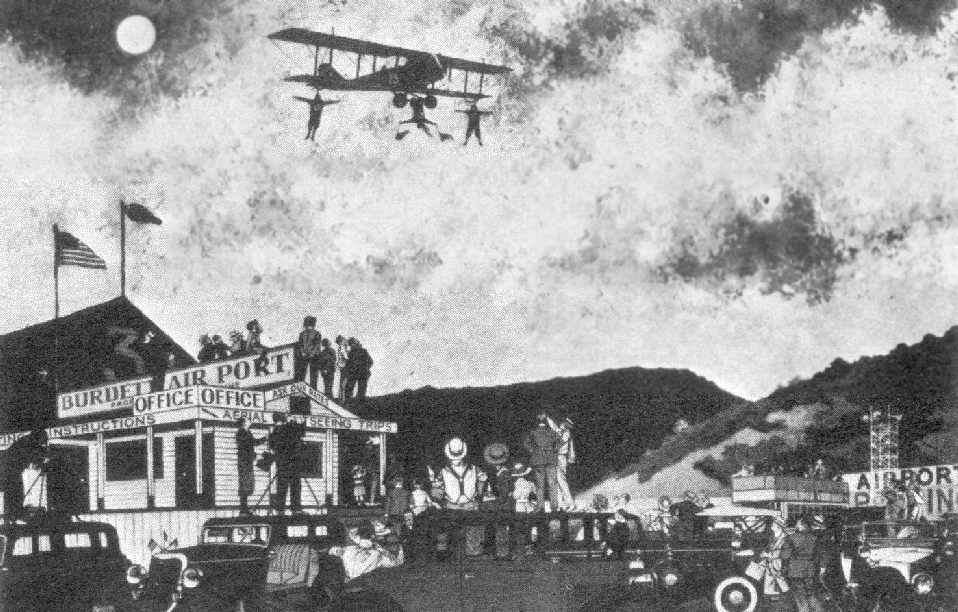

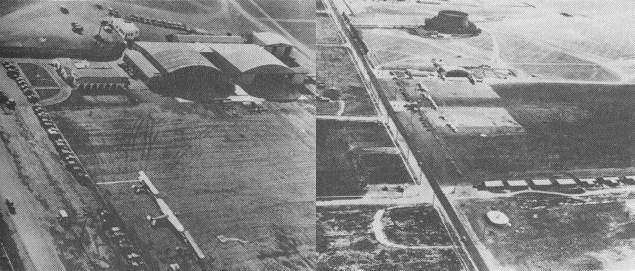

Burdette Airport / Dycer Airport, Inglewood, CA

33.95, -118.31 (Northeast of Hawthorne Airport, CA)

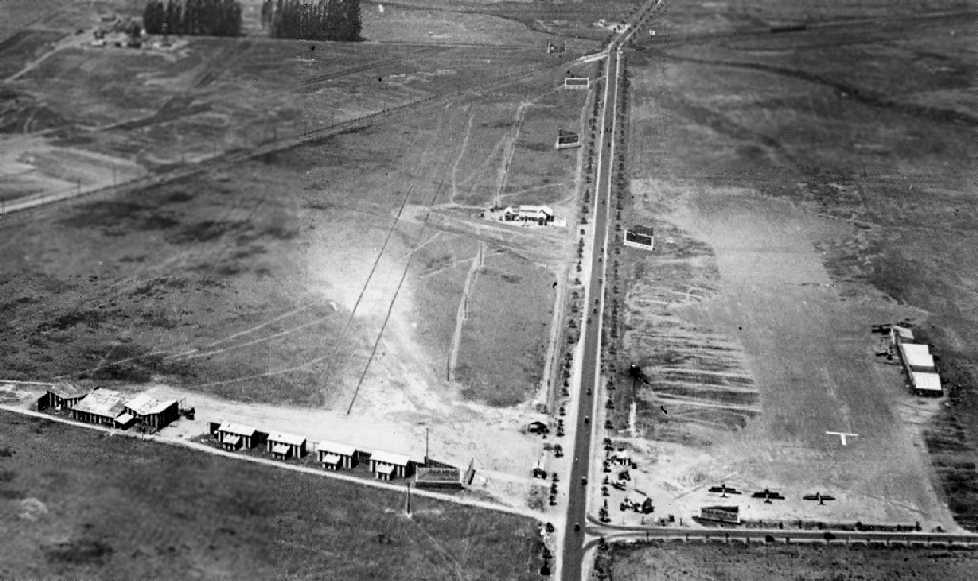

A 1925 aerial view of Burdette Field (courtesy of Mark Hess).

According to Dan MacPherson, the airfield at 94th & Western Avenue

was first inhabited by Burdette Fuller & was called Burdette Field.

Burdette Field was home to the famous stunt team "The 13 Black Cats".

According to Dan MacPherson, “Each member was given a name that had 13 letters: Fronty Nichols, Bon MacDougall, Spider Matlock, etc.”

The 13 Black Cats were a company of flamboyant Los Angeles-based stunt pilots

who defied both superstition & the odds on survival at Burdette Airport in the 1920s.

Lots of footage was taken of the black cats doing various stunts,

and the footage appeared in many movies.

The black cats were involved with motion pictures & received a lot of publicity.

The earliest depiction which has been located of Dycer Airport was a 1925 aerial view (courtesy of Mark Hess).

It depicted 3 biplanes next to a tent & a few small buildings.

According to K.O. Eckland, the Burdette School of Aviation was established in 1925

by Burdette Fuller & Jack Frye as a base for Burdette Airlines.

Fuller sold the field to Jack Frye, who founded Aero Corp, which became TWA.

Burdette Fuller taught Frye how to fly.

After Frye left, Charles Dycer bought the field.

A 1/29/28 photo Burdette Field (courtesy of Mark Hess)

showed a plane on the field in front of a row of hangars, with a large water tank in the background.

A 2/26/28 photo of a rare Brown Mercury C-2 tri-motor at Burdette Field (courtesy of Mark Hess).

A 1929 aerial view looking west at Dycer Airport (courtesy of Dan MacPherson).

It depicted the field as a square grass plot with 2 hangars & several aircraft at the southeast corner.

Hollywood Park was visible in the background.

An undated view of biplanes in front of the hangars of the Burdette Airlines School of Aviation (courtesy of Dan MacPherson).

An undated illustration of a performance of "The 13 Black Cats" at the Burdette Airport (courtesy of Dan MacPherson).

The hangars at Dycer Airport in 1929, courtesy of Dan MacPherson.

An undated aerial view of Dycer Airport, courtesy of Dan MacPherson.

According to Dan MacPherson,

in 1929 this airport was occupied by Aero Corporation & Standard Airlines.

It was the Los Angeles terminal of Standard Airlines, whose routes extended to El Paso, TX.

The Standard Oil Company's 1929 "Airplane Landing Fields of the Pacific West" (courtesy of Chris Kennedy)

described Dycer Field as being owned by C. H. Dycer.

It was said to have 2 natural adobe soil runways,

with the longest being an 1,800' east/west strip.

Three hangars (marked "Dycer") & other small buildings were at the southeast corner.

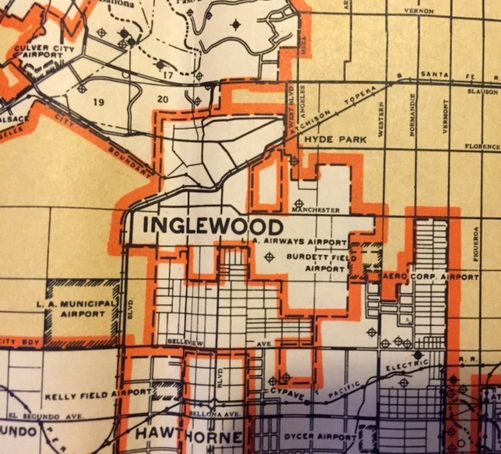

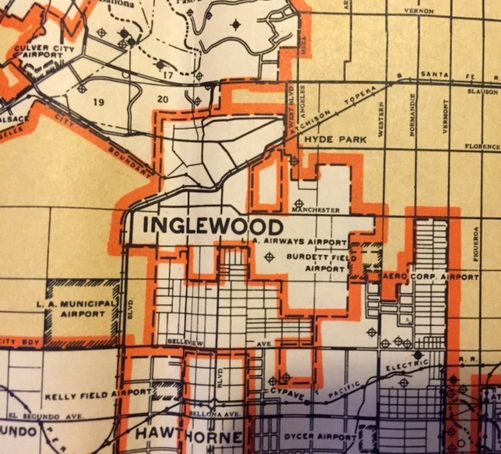

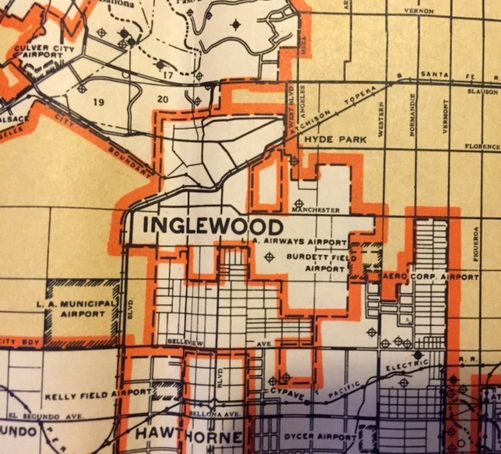

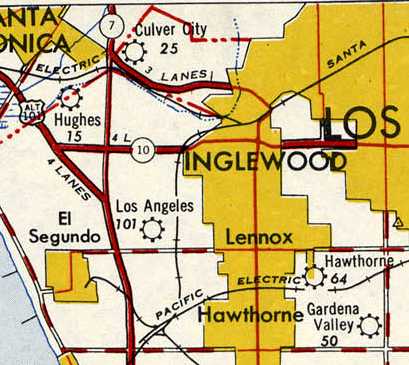

A 1930 LA County Rand McNally street map (courtesy of Kevin Walsh)

depicted “Burdett Field Airport” & “Aero Corp. Airport” as 2 different facilities.

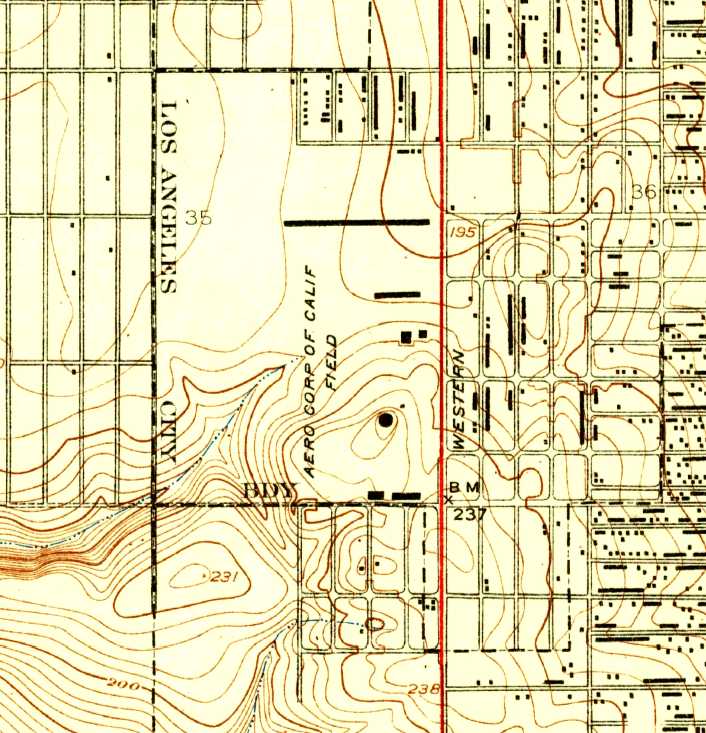

The 1930 USGS topo map (courtesy of Bob Allessi) depicted the “Aero Corp of Calif Field”

as a small hilly property with several buildings along the east side.

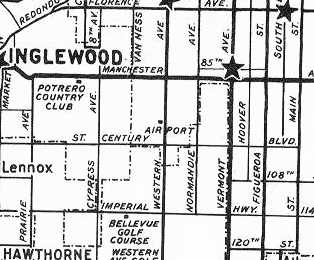

A 1931 street map (courtesy of Gary Alexander) labeled the Dycer Airfield simply as “Airport”.

After Aero Corporation & Standard Airlines moved, the site was taken over by Charles Dycer,

who moved his operations from the field at Western Avenue & 136th Street (later known as Gardena Valley Airport).

An aerial view looking southwest at Dycer Airport from the Airport Directory Company's 1933 Airports Directory (courtesy of Chris Kennedy).

The directory described Dycer Airport as having two 2,600' runways, "one oil, one natural".

The aerial photo in the directory depicted 3 large arch-roofed hangars on the south side of the field,

as well as a long row of 24 individual hangars along the north side of the field.

The manager was listed as the Dycer Brothers.

The operators were the Dycer Flying School (instruction),

Dycer Airport (passenger flights, charter trips, aircraft sales, parts, and supplies),

and California Aircraft Repair Company (all types of general repair work).

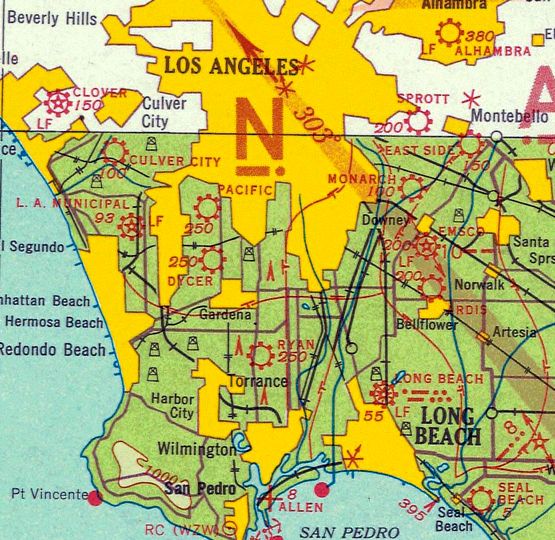

The only aeronautical chart depiction which has been located of Dycer Airport was on the 1934 San Diego Airway Chart (courtesy of Roger Connor).

The last photo which has been located of Dycer Airport was a 1935 view of a Ryan ST & M-1.

Ken Barber recalled, “I lived on 94th Place just just 4 short blocks from Dycer.

I recall when a Lincoln Page coming in for a landing had a smaller aircraft in its blind spot underneath

and sat right down on top of it in its decent & they crashed in the backyard of a house not to far from where I lived.”

Richard Reynolds recalled, “I lived on 95th Street just a couple of blocks from Dycer Airport. In 1936 I had my first airplane ride at Dycer.

It was a real thrill living nearby as all of the planes approaching the field flew over our house.

Prior to WWII many of the local high school boys would take flying lessons at Dycer.

My uncle did so & later became a B-24 pilot. Cars cost too much but it took just a couple of dollars for a [flying] lesson.”

The Airport Directory Company's 1937 Airports Directory (courtesy of Bob Rambo)

described Dycer Airport as having 2 sod runways, with the longest being a 2,600' northeast/southwest strip.

The aerial photo in the directory depicted a group of hangars on the east side of the field,

one of which was described as having "Dycer Airport" painted on the roof.

The Airport Directory Company's 1938 Airports Directory (courtesy of Jonathan Westerling)

described Dycer Airport as a rectangular sod area, measuring 1,469' north/south by 2,644' east/west.

A hangar was said to have "Dycer Airport" painted on the roof.

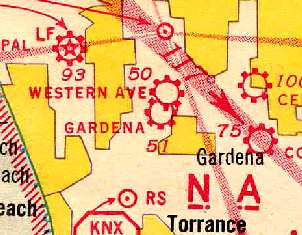

Burdette Airport, as depicted on a 1940 street map (courtesy of Kevin Walsh).

Dycer Airport was apparently closed at some point between 1938-41,

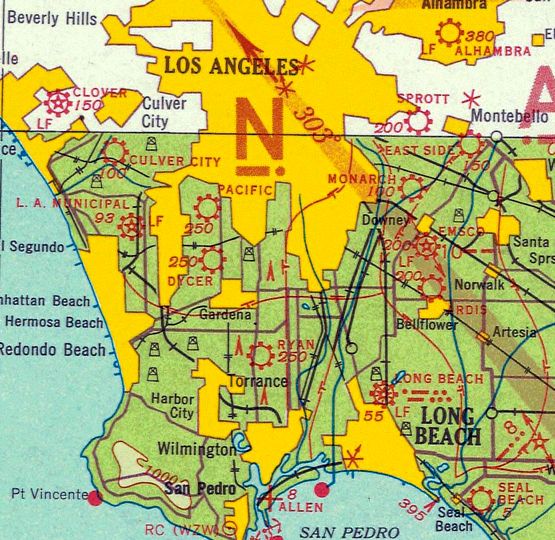

as it was not depicted on the 1941 LA Sectional Chart (courtesy of Chris Kennedy).

Richard Reynolds recalled, “Dycer Airport... must have closed about the time WWII began

because we used to hike through the area to an old gun range at the western end of the field & pick up shell casings.”

The 1948 USGS topo map showed the site of Dycer Airport covered by new streets,

and a 1952 aerial photo showed the site of Dycer Airport had been covered with dense housing.

A March 2004 USGS aerial photo showed the site of Dycer Airport to have been densely redeveloped.

Not a trace of the airfield appeared to remain, with one possible exception:

a building with a white arched roof is visible on the west side of Western Avenue, between 91st & 92nd Streets.

It appears to resemble a hangar - could this be a former Dycer Airport hangar,

possibly relocated a few blocks north & reused?

The site of Dycer Airport is bounded by Western Avenue on the east, Van Ness Avenue on the west,

93rd Street on the north, and 96th Street on the south.

See also: http://www.soc.org/opcam/08_sps96/mg08_aerial.html

____________________________________________________

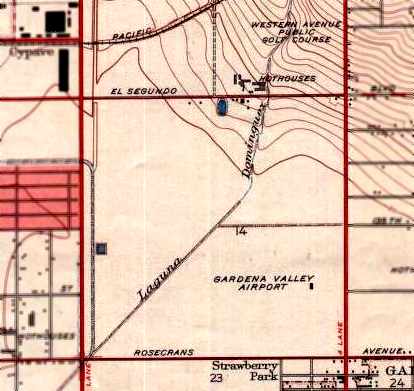

33.89, -118.32 (Southeast of Hawthorne Airport, CA)

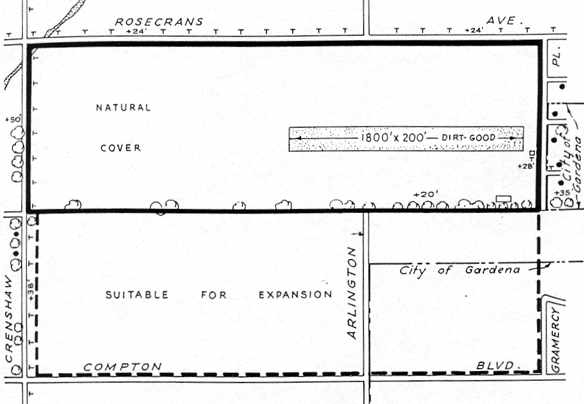

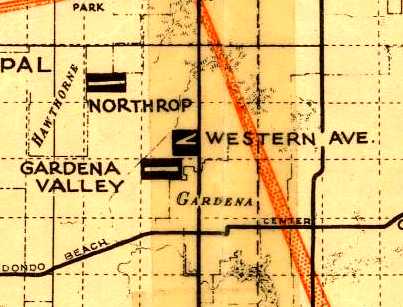

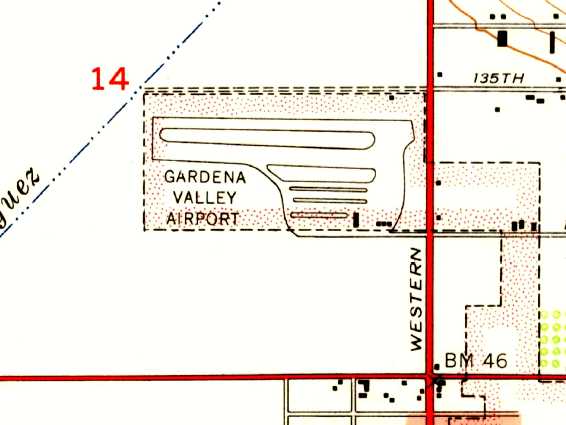

What was known at the time as "Gardena Valley Airport",

as depicted on a 1939 report on existing & proposed airports by LA County's Regional Planning Commission

(courtesy of Chris Killian, via Dan MacPherson).

Photo of the airport is not available.

The date of construction of Gardena Airport is unknown.

It was located only 2 miles south of the Hawthorne Airport.

Gardena Airport was a separate & distinct airfield from Gardena Valley Airport,

which was located one mile northeast.

The 1927 USGS topo map did not depict any airfield at this location.

The Standard Oil Company's 1929 "Airplane Landing Fields of the Pacific West" (courtesy of Chris Kennedy)

described a Gardena Commercial Airport as being located "1.5 miles south" of the town of Gardena,

which may have been this airport.

It was said to be operated by Airylite, Inc., and to have a 2,000' east/west graded runway.

A hangar was said to be marked "Airylite Gardena" & "Shell".

A 1939 report on existing & proposed airports

by LA County's Regional Planning Commission (courtesy of Chris Killian, via Dan MacPherson)

labeled the field as "Gardena Valley Airport".

The description of Gardena Valley Airport said:

"This recently established airport can be developed as a capacious Class 2 airport, principally for private & student flying.

It is used at present by the University of Southern California for student training under the C.A.A. program.

Drainage problems must be solved, and depend largely on major drainage improvements in the Gardena Valley.

A well developed airport at this site would help to solve the problem of private hangar space

that will result from the transformation of Los Angeles airport into a transport line terminal."

It was depicted as having a single 1,800' dirt east/west runway,

southwest of the intersection Rosecrans Avenue & Grammercy Place.

The field was described as having a hangar & an office.

The owner was listed as Elva Kistleman, the lessee as E.G. Kidwell,

and the operators as E.G. Kidwell, Eager, Hanson, and Untermeyer.

An additional plot of land, extending to the south to Compton Boulevard, was labeled as "suitable for expansion".

Gardena Valley Airport was depicted on the 1939 LA County Airports Map as having a single east/west runway.

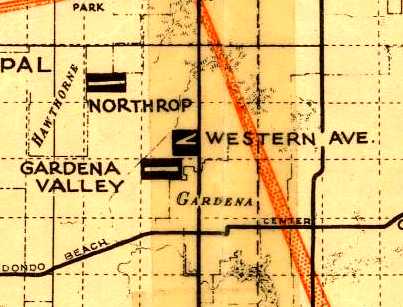

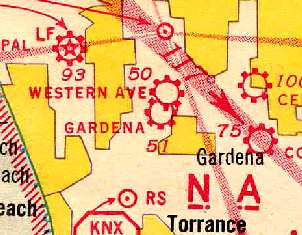

"Gardena Valley" Airport, as depicted on the 1940 San Diego Sectional Chart (courtesy of Chris Kennedy).

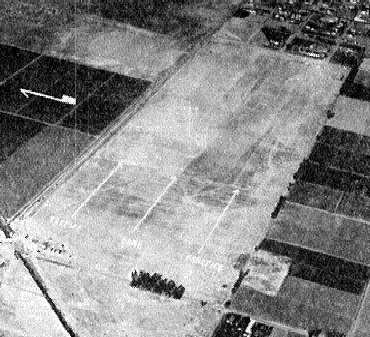

An undated aerial view looking northeast at Gardena Airport from the Airport Directory Company's 1941 Airports Directory (courtesy of Jonathan Westerling).

Note the 3 different runways annotated, for takeoff, landing, and practice.

"Gardena" Airport, as depicted on the 1941 LA Sectional Chart (courtesy of Chris Kennedy).

"Gardena" Airport was depicted as an auxiliary airfield on the 1944 LA Sectional Aeronautical Chart (courtesy of John Voss).

According to Dan MacPherson , the original Gardena Airport closed just after WW2.

It was no longer depicted at all on the 1948 San Diego Sectional Aeronautical Chart (according to Chris Kennedy)

nor on the 1952 USGS topo map.

By the time of a 1952 aerial photo, the site of Gardena Airport had been covered with dense housing.

A March 2004 USGS aerial photo showed the site of Gardena Airport is located in what has become a densely developed area,

and not a trace of the airfield appears to remain.

The site of Gardena Airport was bounded by Rosecrans Avenue on the north,

Compton Avenue (Marine Avenue) on the south,

Crenshaw Boulevard on the west, and Grammercy Place on the east.

____________________________________________________

Dycer Airport / Universal Airport / Gotch's Airport / Western Avenue Airport /

Gardena Valley Airport, Gardena, CA

33.904, -118.314 (Southeast of Hawthorne Airport, CA)

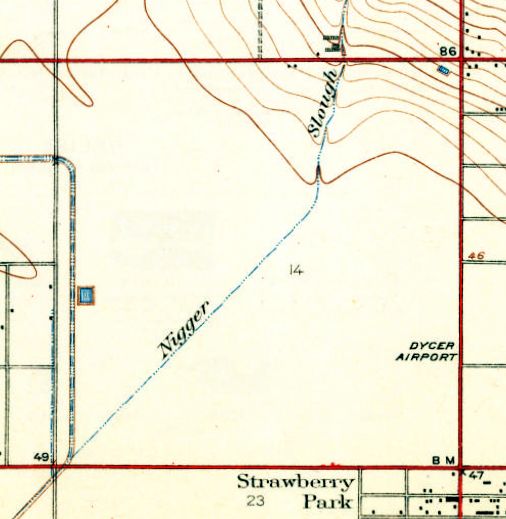

Dycer Airport, as depicted on the 1927 Commerce Department Airway Bulletin.

Gardena Valley Airport was a separate & distinct airfield from Gardena Airport,

which was located one mile southwest.

In the 1920s, this airport was first known as Dycer Airport.

The 1924 USGS topo map did not depict any airfield at this location.

In 1926, Charles Dycer developed the Dycer Sportplane,

which may have been a civil conversion of the Curtiss JN-4D.

The Dycer Airport company eventually moved to a new site further north at Western Avenue & 136th Street,

which became known as Dycer Airport.

The earliest depiction which has been located of Dycer Airport was on the 1927 Commerce Department Airway Bulletin.

It depicted Dycer Airport as having a rectangular area on the eastern half marked “Good landing field no obstructions”,

along with a larger rectangular area on the western half of the block labeled “Cultivated emergency landing”.

A shack, 2 small hangars, and a windsock were depicted on the east side.

The Standard Oil Company's 1929 "Airplane Landing Fields of the Pacific West" (courtesy of Chris Kennedy)

listed a "Universal Airport" as being located "1 mile southeast of Gardena",

which may have been this airport.

It was said to be operated by the Universal Institute of Aeronautics.

The airfield area was said to consist of a "Main field" (a 3,100' north/south by 2,500' east/west graded area)

along with an "Auxiliary field" (a 2,000' north/south graded area).

Four individual & 2 large steel hangars were said to be located along the north side of the main & auxiliary fields,

marked "U. I. A.".

The label "Dycer Airport" was depicted on the 1930 USGS topo map (courtesy of Francis Blake),

but no runways or anything else was depicted.

Dycer Airport, as depicted on a 1930 LA County Rand McNally street map (courtesy of Kevin Walsh).

A 1931 street map (courtesy of Gary Alexander) labeled the airfield at this location simply as “Airport”.

An undated photo (courtesy of Ken Nadvornick) of 2 Lincoln-Page LP-3 biplanes marked “Dycer Airport”.

Ken reported, “In the 1980s I was working as a commercial photographic darkroom printer in Cypress, CA.

A customer came by with a stack of old 5x7 glass plate negatives she had found in a deceased relative's attic. She asked if they could be printed.

The [picture above] is from one of the resulting contact prints I made for her.

It's a rather strikingly dynamic photograph, what with an operating aircraft engine

and a pilot holding his hands over his ears against the noise & prop wash.”

According to Dan MacPherson, this airport became known as Gotch's Airport, in 1936.

It was owned by Gus Gotch, a 1930's air racer.

It was on a flood plain & was under water during the rainy season.

It was next known as Western Avenue Airport (one of several with that name over the years).

That is how it was labeled on a 1939 report on existing & proposed airports

by LA County's Regional Planning Commission (courtesy of Chris Killian, via Dan MacPherson).

The description of Western Avenue Airport said:

"This Class 1 airport, only a short distance north of the Gardena Valley Airport,

is subject to serious drainage problems, standing under water for fairly long periods every winter.

It is believed that this district does not warrant maintenance of 2 airports in such close proximity.

There is little to chose between these two,

but the drainage is believed to be more satisfactory at the other site.

The choice of the Gardena Valley Airport for use in the C.A.A. student training program

resulted in the elimination of the Western Avenue Airport from the Master Plan."

Western Avenue Airport was depicted as having 3 dirt runways forming an "X"

(with the longest being a 1,600' east/west strip)

at the southwest corner of Western Avenue & 135th Street.

The field was described as having 2 hangars, and office, and a repair shop.

The owner was listed as Charles Dycer,

and the operator was listed as Karl Christianson.

A much larger plot of land, extending to the south to Rosecrans Avenue & to the west to the drainage ditch,

was labeled as "suitable for expansion".

A square portion of this land just to the southwest of the runways was labeled "Model Airplane Airport".

Western Avenue Airport was depicted on the 1939 LA County Airports Map as having 2 runways.

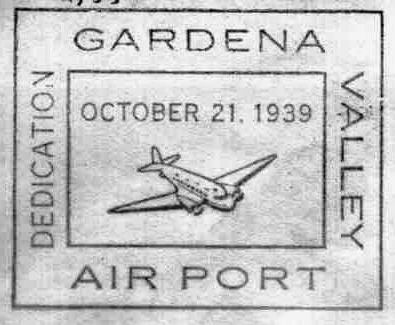

A postmark commemorated the 10/21/39 Dedication of Gardena Valley Airport.

"Western Ave" Airport, as depicted on the 1940 San Diego Sectional Chart (courtesy of Chris Kennedy).

A 12/24/40 view of a flooded Western Avenue Airport.

"Western Ave" Airport, as depicted on the 1941 LA Sectional Chart (courtesy of Chris Kennedy).

A circa 1945 photo of a Vega 35 at Gardena Valley Airport by Harry Gordon.

Harry recalled, “My first open cockpit flight was in this Vega 35, based at Gardena Valley Airport.

The airplane was a North American design.

The prototype was the NA-35, built as a potential primary trainer for the Army, but the Ryan ST was chosen instead (both planes used the Menasco engine).

NAA then sold the design & manufacturing rights to Vega, but only 5 Model 35s were built.

NAA reportedly used the NA-35 wing design for the Navion.

The plane bears the airport emblem 'Fly Gardena Valley Airport' which was also on the Cub I flew for my first solo.”

By 1946 it was known as Gardena Valley Airport, as depicted on the 1946 USGS topo map.

An undated photo of a pilot in front of an unidentified plane marked “Gardena Valley Airport, Pacific Pilots Plan” (courtesy of Jim Osborne).

A 1946-47 aerial view of Gardena Valley Airport, taken by Harry Gordon “at 800' from the downwind leg.

That is Western Avenue crossing diagonally from top to bottom in the photo.

My photos were taken, unfortunately, with a box camera,

which had a shutter speed of probably less than 1/50 second, not good in a vibrating airplane.

The big hangar was built early in 1946.

The photo plane was a war surplus Aeronca L-3, one of 2 or 3 rented for $6/hr by a Mr. Whitmore, whose flight office was his car.”

The 1948 USGS topo map labeled it as Gardena Valley Airport.

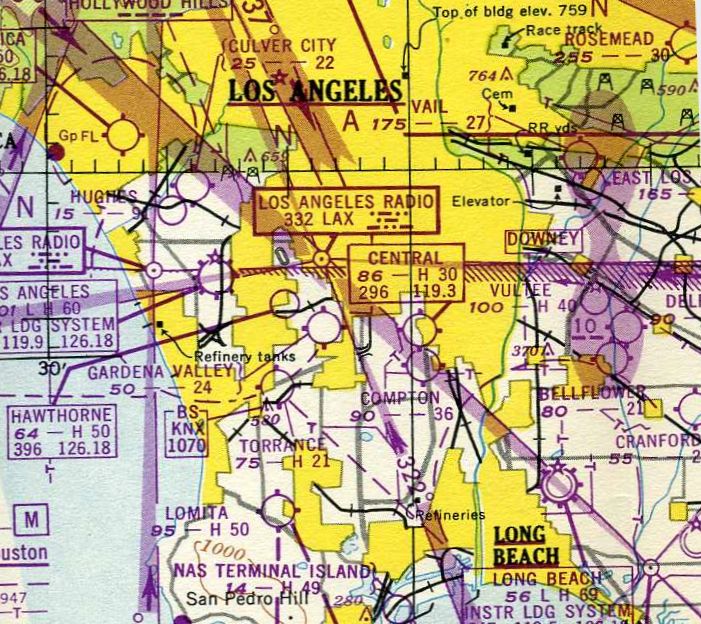

The last aeronautical chart depiction which is available of Gardena Valley Airport was on the February 1949 LA Sectional Chart,

which depicted Gardena Valley Airport as having a 2,400' unpaved runway.

An undated (late 1940s?) photo by Chas Jones of a Cessna T-50 Bamboo Bomber at Gardena Valley Western Avenue Airport (courtesy of Dan MacPherson).

Note the large hangar in the background. Dan MacPherson noted, “The hangar in the background shows up in the Don Downie article (Flying Magazine May 1947).”

An undated (late 1940s?) photo by Chas Jones of a Cessna T-50 Bamboo Bomber presumably at Gardena Valley Western Avenue Airport (courtesy of Dan MacPherson).

Dan MacPerson reported, “The pictures were given to me by Sylvia Weeks, who was married to the son of Floyd Wardlaw, who ran an aircraft parts business since WWII.

He was obviously looking at a Bamboo Bomber to buy. I assume by the cracked ground that both photos are at the same location, Western at 136th.

I have pictures of the neighboring model airplane field; it shows the same cracking on the ground.”

The last photo which is available showing Gardena Valley Airport was an undated aerial view looking north from the 1950 Air Photo Guide (courtesy of Kevin Walsh).

The guide described Gardena Valley Airport as having a 2,600' turf east/west runway, and listed the manager as A.L. Sharp.

Gardena Valley Airport was depicted as an active airfield on the 1950 LAX Chart (according to Bob Cannon).

The 1952 USGS topo map depicted Gardena Valley Airport as having a single east/west runway & parallel taxiway,

with a ramp & 2 small buildings on the southeast side.

A 1952 aerial photo showed Gardena Valley Airport having a single east/west runway, with more than 30 light aircraft on the south side.

Four individual T-hangars were located on the north side of the runway, and 2 larger hangars were located on the southeast.

Gardena Valley Airport was still depicted on a 1954 LA road map (courtesy of Dan MacPherson),

but that does not necessarily mean it was still an active airport at that time.

Gardena Valley Airport was evidently closed (for reasons unknown) at some point between 1952-54,

as it was no longer depicted at all on the September 1954 LA Sectional Chart (courtesy of Chris Kennedy),

nor depicted at all on a 1957 street map (courtesy of Chris Kennedy).

A 1963 aerial photo showed an oval racetrack had been built on the eastern portion of the Gardena Valley Airport property.

The larger hangar on the southeast side still remained intact,

but the 2nd hangar on the southeast side & the T-hangars on the north side had been removed at some point between 1952-63.

By the time of the 1965 USGS topo map, buildings & streets covered the site of Gardena Valley Airport.

A 1972 aerial photo showed the racetrack had been replaced by large buildings at some point between 1963-72,

but Gardena Valley Airport's largest hangar remained standing on the southeast side.

The last photo which has been located showing any remaining trace of Gardena Valley Airport was a 1980 aerial view,

which showed the hangar remained standing on the southeast side.

A 1994 aerial view showed Gardena Valley Airport's last hangar was removed at some point between 1980-94,

erasing the last trace of this little airport.

As seen in the March 2004 USGS aerial photo, the site of Gardena Valley Airprot was densely redeveloped,

and not a trace of the airfield appeared to remain.

The site of Gardena Valley Airport is bounded by 135th Street on the north, 139th Street on the south,

Van Ness Avenue on the west, and Western Avenue on the east.

____________________________________________________

Rogers Airport, Los Angeles, CA

34.06, -118.36 (Northeast of Los Angeles International Airport, CA)

A 1920 aerial view of Rogers Airport.

According to K.O. Eckland, Rogers Airport opened in 1918

at the northwest corner of Wilshire Boulevard & Crescent Avenue (now Fairfax Avenue).

It was an unpaved field measuring 3,681' x 1,500'.

The earliest depiction which has been located of Rogers Airport was a 1920 aerial view,

showing an unpaved field with a row of buildings along the edge.

Rogers Airport was not depicted on the 1921 USGS topo map.

A 1922 view looking west toward the general office & hangars of Rogers Airport, with 2 unidentified biplanes on the field.

A circa 1922 photo of a biplane at Rogers Airport, with the buildings of Rogers Aircraft Company in the background.

According to Marc Carlson (Special Collections of the McFarlin Library), “It's a Nieuport 28',

one of 2 listed as being owned by the Rogers Aircraft Inc. in the Aerospace Year Book for 1922.

You'll notice the insignia on the plane matches the one on the building.”

Also note the oil wells in the background.

A 1922 aerial view looking west at Rogers Airport (courtesy of Bob Beecher).

A circa 1922 aerial view looking northeast at Rogers Airport (courtesy of Kevin Walsh).

A circa 1920s aerial view of Rogers Airport showed a row of hangars & a large number of aircraft & visitors – some type of show?

A 1923 LA Chamber of Commerce table of LA-area airfields (courtesy of K.O. Eckland)

described Rogers as having an 1,800' east/west runway.

An undated painting by Ted Grohs (courtesy of Ken Morrison) of Omar Locklear during a headstand on the wing of a Jenny

above the De Mille & Chaplin Airports on Wilshire Boulevard & Crescent Avenue.

Rogers Airport (as well as a dense grouping of other vintage airfields),

as depicted on the 1929 "Rand McNally Standard Map of CA With Air Trails" (courtesy of Chris Kennedy).

The map Rogers Airport as being operated by Rogers Aircraft, Inc.,

and being 3,681' x 1,500' in size.

Industrialist Howard Hughes learned to fly from pioneer aviators, including Moye Stephens, at Rogers Airport in the early 1930s.

Rogers Airport was evidently closed (for reasons unknown) at some point between 1929-39,

as Bob Beecher reported, “There are several pictures of the intersection up to 1939

when the May Company department store was built & the airport was long gone, replaced by other buildings.

The airport building (the one on the angle) had turned into a cafe.”

Rogers Airport was no longer depicted on a 1931 street map (courtesy of Gary Alexander),

the 1932 USGS topo map, a 1940 LA street map (courtesy of Dan MacPherson),

or the 1941 LA Sectional Chart (courtesy of Chris Kennedy).

By the time of a 1948 aerial photo, the site of Rogers Airport had been covered with buildings.

According to Bob Beecher, the former Rogers Airport building “later was a Simon's Sandwiches drive-in through the 1950s.”

As seen in the March 2004 USGS aerial view,

the site of Rogers Airport is in what has become a very densely developed area,

and not a trace of the former airport remains.

____________________________________________________

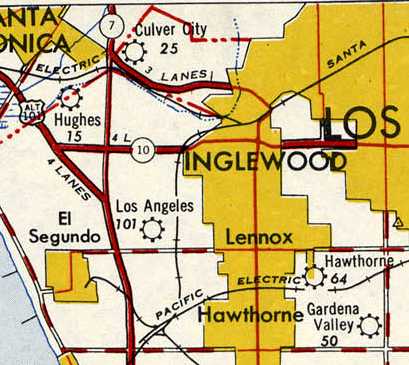

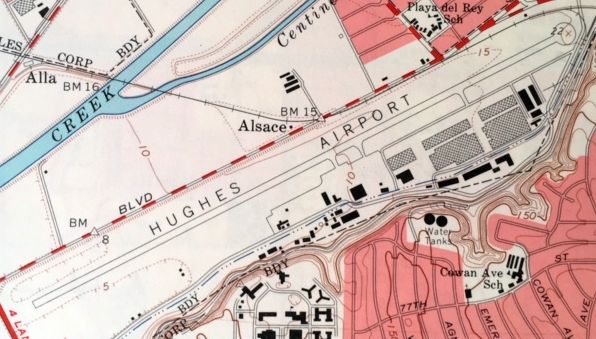

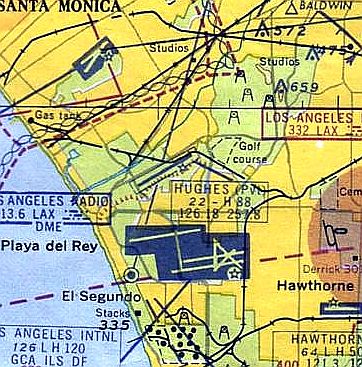

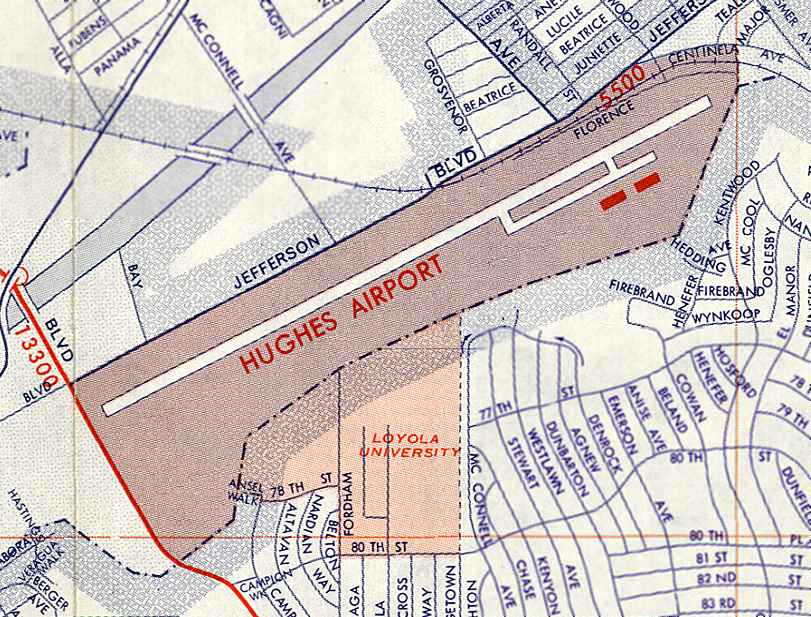

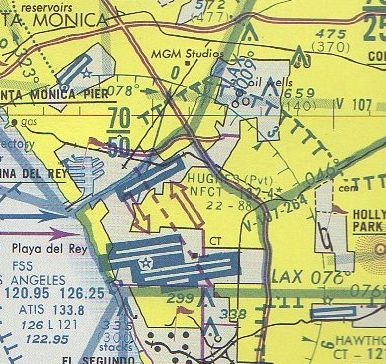

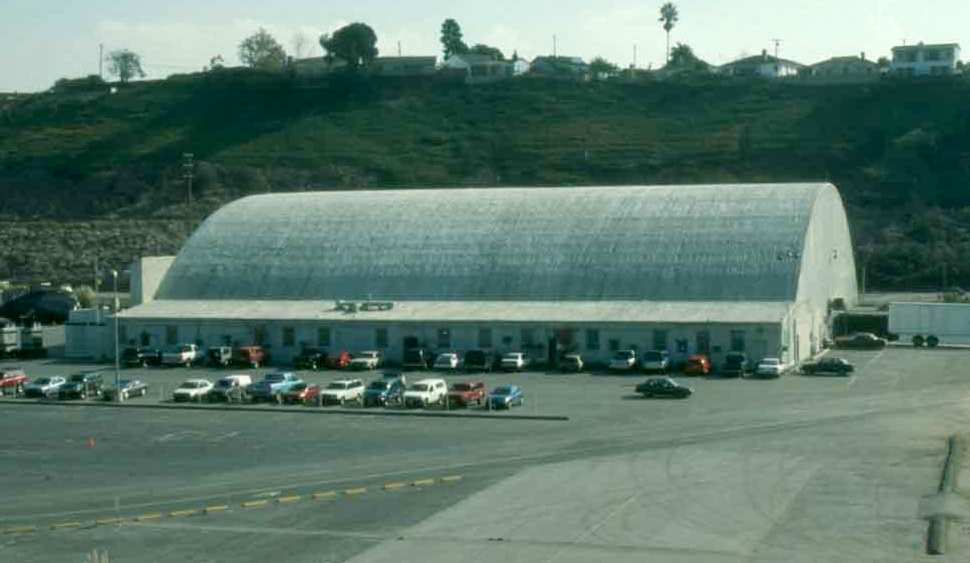

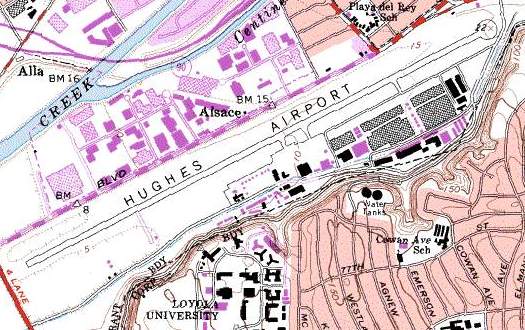

Hughes Airport, Culver City, CA

33.98, -118.414 (North of Los Angeles International Airport, CA)

Hughes Airport, as depicted on a 1940 LA street map (courtesy of Dan MacPherson)

Young industrialist Howard Hughes established a new aircraft division within his Hughes Tool Company in 1932.

The first facilities of the new aircraft division were in space rented from the Lockheed Company in Burbank.

By 1939 the Hughes Tool Company was engaged in a full-scale program to develop a high speed fighter bomber using Duramold plywood,

a plastic-bonded plywood molded under heat & high pressure.

This became the DX-2, later known simply as the D-2.

To build the D-2, the Burbank facility would be insufficient, and Hughes sought a much larger facility.

in 1940 Hughes purchased 380 acres (although other sources put the initial purchase as over 1,000 acres)

of the Ballona Wetlands just west of Culver City for $500,000.

Hughes recognized the area as one of the few large tracts of remaining undeveloped land in Los Angeles.

The high water table made it necessary to sink 50' pilings into the wetlands

to support Hughes’ buildings & reroute the course of the Centinela River,

which flowed through the site every spring & flooded it.

On his new land Hughes constructed a 60,000 square foot air conditioned, humidity-controlled aircraft plant with an adjacent grass runway.

All but one of the major industrial buildings of the Hughes complex were designed by architect Henry Gogerty,

who had previously designed the beautiful Grand Central Air Terminal building in nearby Glendale.

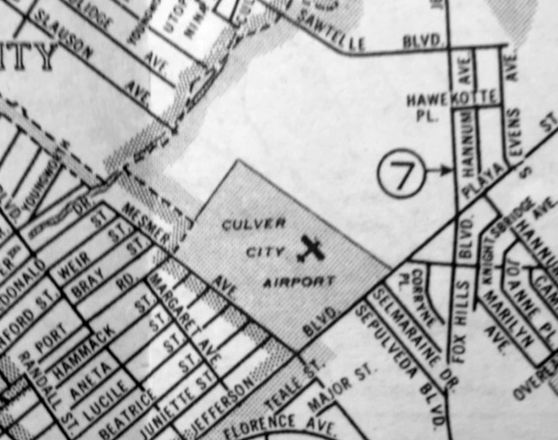

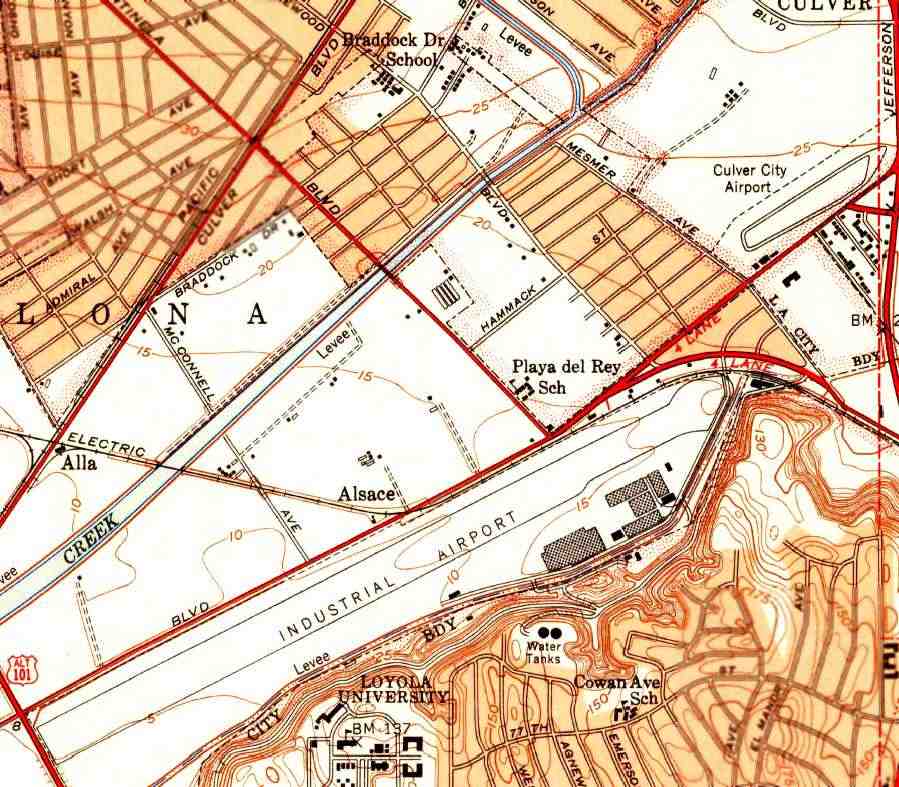

The earliest depiction of the Hughes Airport which has been located

was on a 1940 LA street map (courtesy of Dan MacPherson).

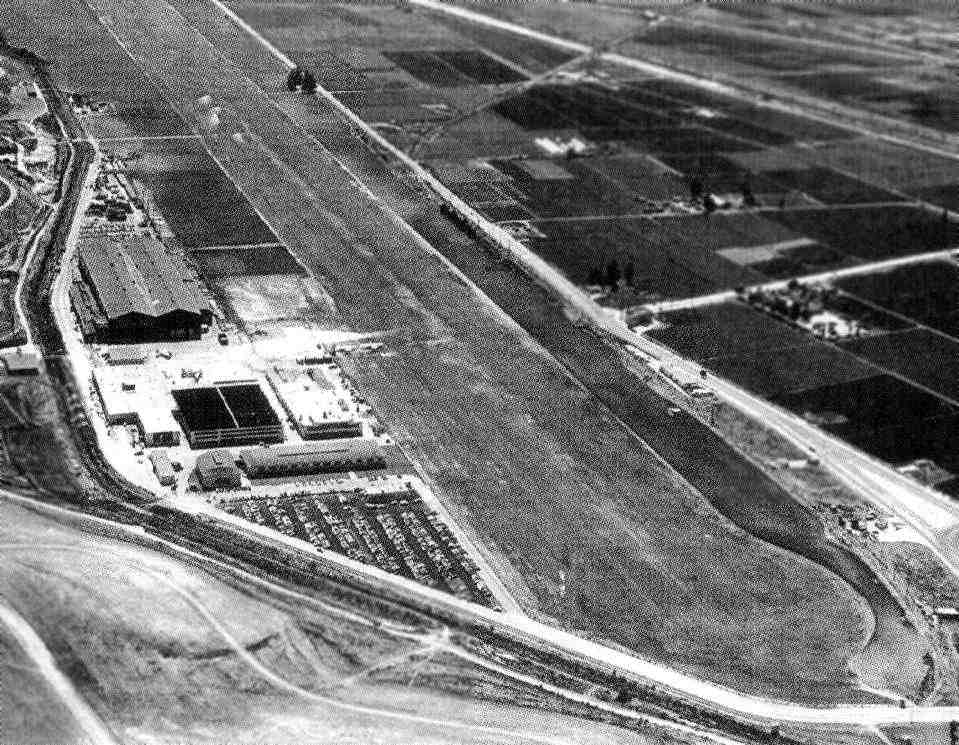

The earliest photo which has been located of the Hughes Culver City facility was a June 1941 aerial view looking west,

showing the Hughes plant under construction & the runway on the right side.

A 1941 photo of the Hughes Culver City plant under construction (UNLV Library Special Collections).

By the weekend of 7/4/41, all of the operations of Hughes Aircraft were relocated from Burbank to the new Culver City Plant.

The Hughes Culver City plant had an initial workforce of just 250 employees (later to grow into the thousands).

The D-2 was built in secret at the Hughes Culver City factory

with longtime Hughes associate, Glenn Odekirk, providing engineering inputs.

The fighter that emerged from the Hughes experimental shop looked like a scaled-up P-38 Lightning

and, on paper, sported similar performance potential.

The D-2 had a twin-boom configuration, powered by a pair of 2,000 hp Pratt & Whitney R-2800s.

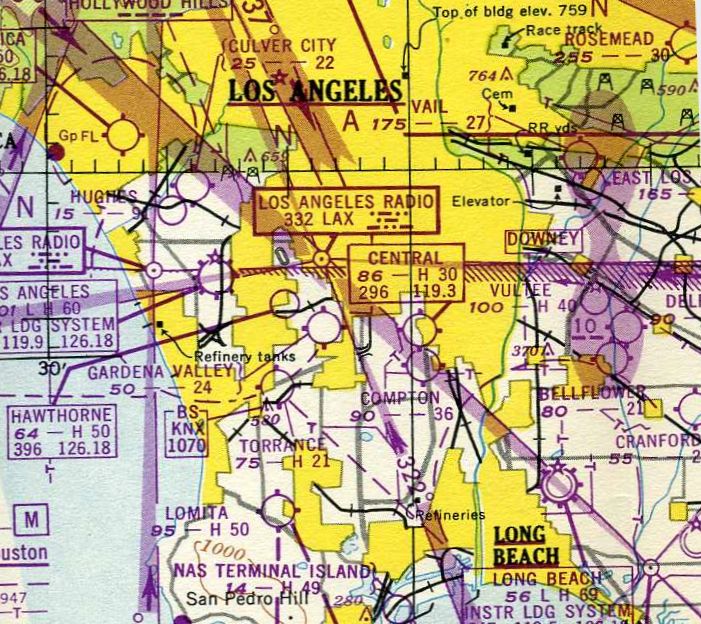

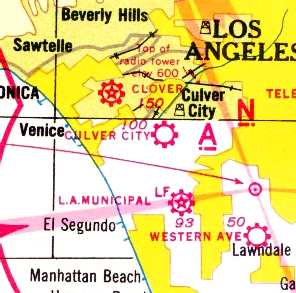

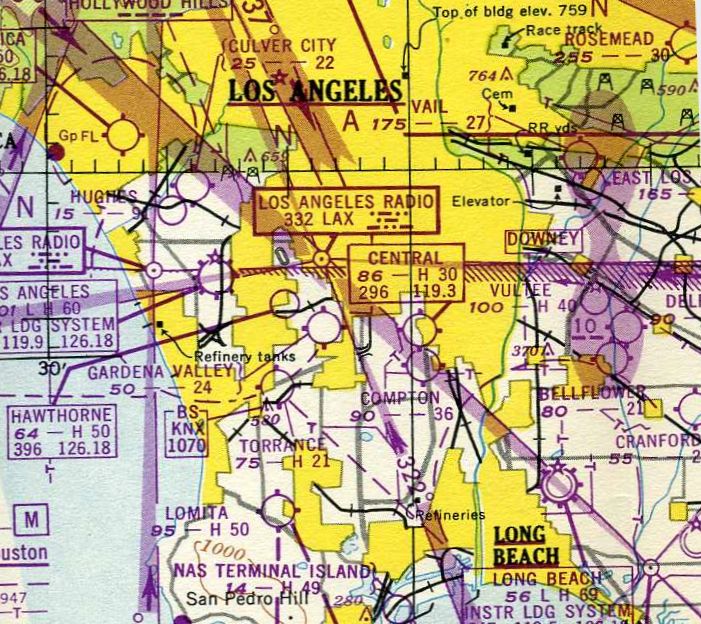

Hughes Airport, as depicted on the 1941 LA Sectional Chart (courtesy of Chris Kennedy).

The Hughes Airport was not depicted at all on the 1942 USGS topo map

(but that was most likely a case of censorship due to wartime security concerns).

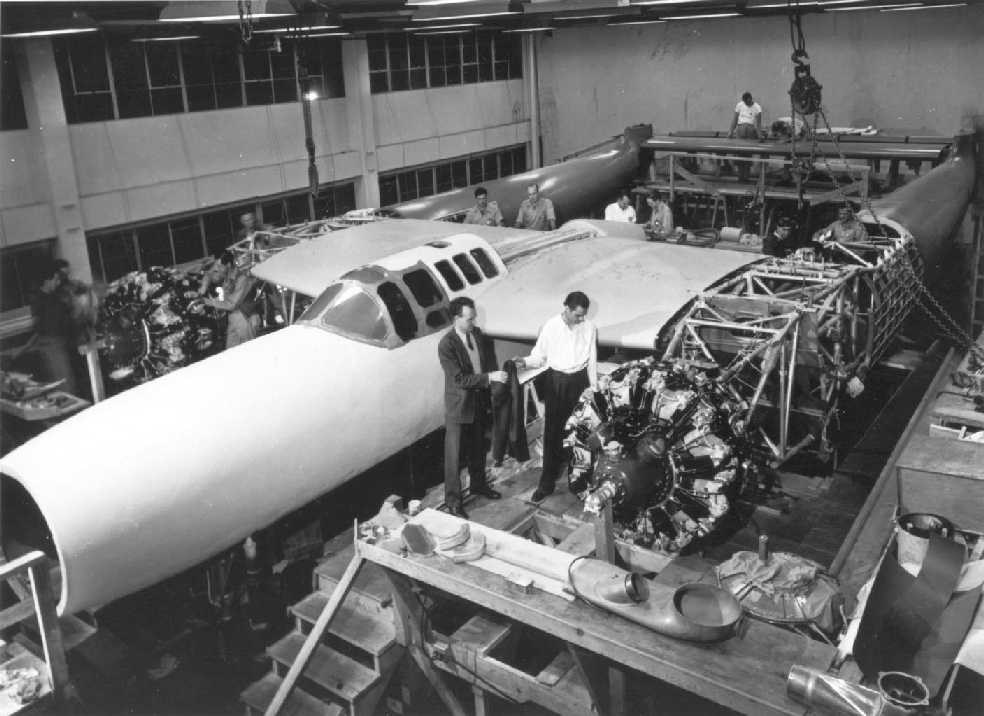

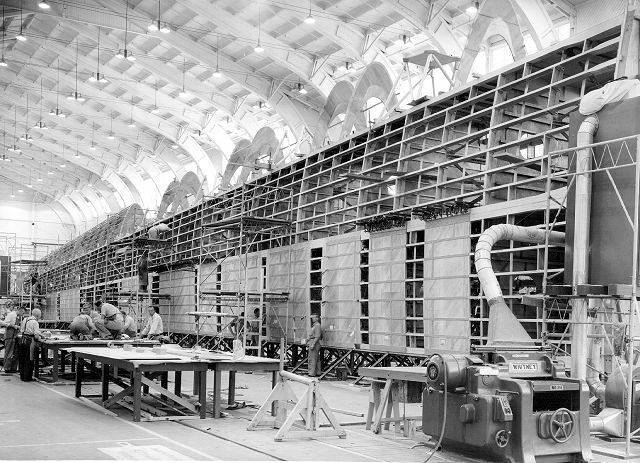

The earliest photo which has been located of the interior of the Hughes Culver City plant

was a circa 1942 photo of Howard Hughes inspecting the prototype of the Hughes D-2 in the Hughes Culver City factory.

When the D-2 prototype was ready for final assembly in May 1943,

it was was relocated to Hughes' secretive facility at Harper Dry Lake in the Mojave Desert,

from which it also conducted its flights.

In 1943, Hughes built the world’s longest private runway at Culver City.

Runway 5/23 was 9,600' long - nearly 2 miles in length.

It was not paved for its first few years,

because Hughes believed that paved runways imparted unnecessary stress on an aircraft's landing gear.

He reportedly had to add fill regularly to keep the ground solid.

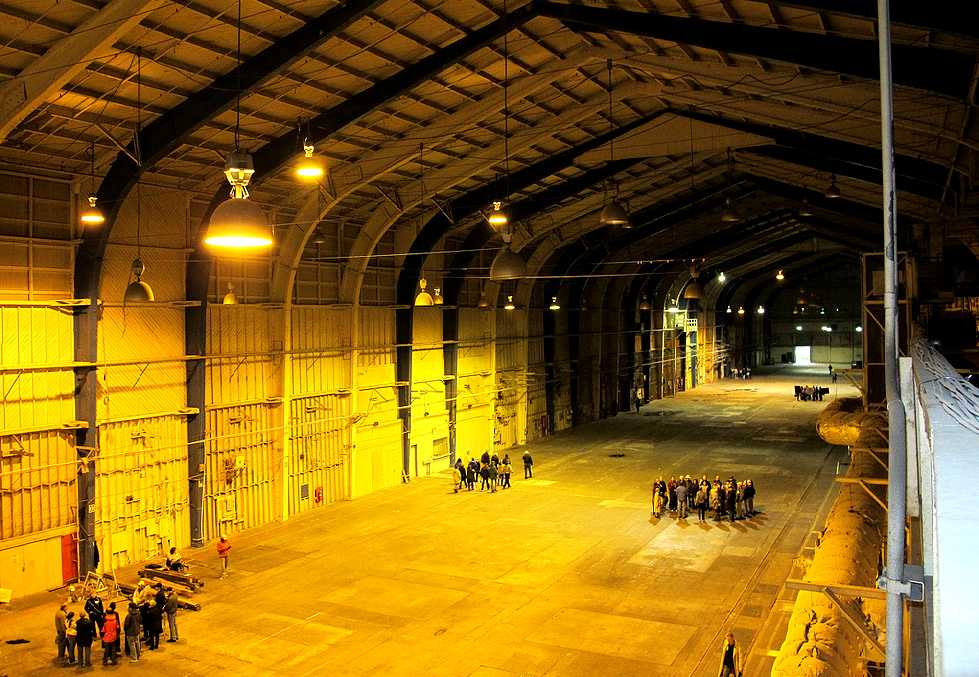

Building 15 (also known as the Hughes Cargo Building) was built in 1943.

It was the Hughes plant’s signature structure.

It was a giant double-gabled hangar, measuring 742' x 248', with Hughes’ name painted on the roof,

and was one of the world's largest wooden buildings.

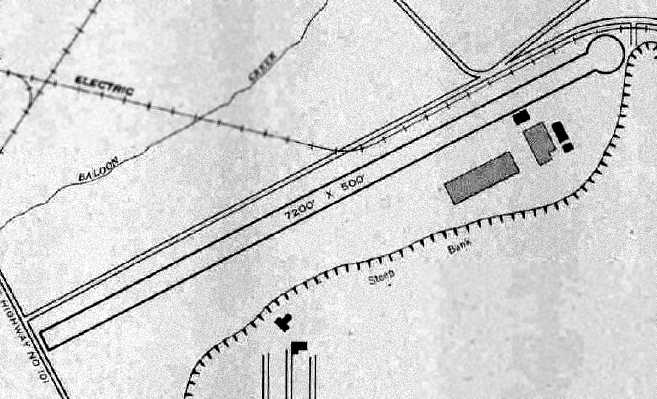

The 1945 AAF Airfield Directory (courtesy of Scott Murdock) described Hughes Airport

as a 380 acre field within which was a single 7,200' turf northeast/southwest runways.

The field was said to have a single 150' x 110' concrete & steel hangar,

and the massive Building 15 & three other buildings were depicted on the southeast side.

The airport was described as being privately owned & operated.

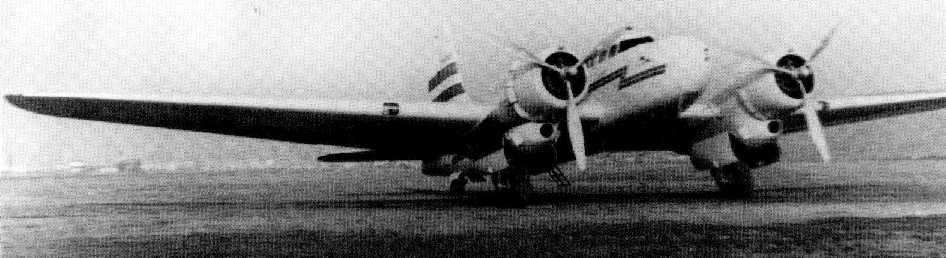

In 1945 the Hughes Tool Company purchased at least 5 surplus Douglas B-23 Dragon bombers,

and converted by the Aircraft Division into transports for the use of Hughes & his top executives.

They were favored by Hughes because of their speed & range: a cruise speed of 310 mph & a max range of 2,750 miles.

An undated (circa 1940s) photo showing a wing of the Hercules flying boat under construction within the Culver City assembly building.

A July 1945 photo of workers putting the finishing touches on the 320' wingspan for the seaplane Hercules within the Culver City assembly building (courtesy of Kevin Walsh).

One of the most famous projects to come out of the Hughes Culver City facility was the HK-1 Hercules flying boat

(better known as the "Spruce Goose").

As WW2 continued to rage, with the supply of strategic metals becoming constrained,

Hughes became convinced that wood would be a logical substitute to replace metal in the construction of aircraft.

He formed a joint venture with Henry Kaiser to develop a flying boat, which could serve as an "air bridge",

linking the US with overseas allies & bypassing the U-boats which threatened shipping traffic.

The aircraft which was developed, the HK-1 Hercules, was the largest airplane ever built

(and continues to have the largest wingspan of any aircraft to the present day).

Its entire airframe was made of laminated wood.

The HK-1 was built in the giant Building 15 (also known as the Hughes Cargo Building).

As large as the Cargo Building was, it wasn’t quite big enough to house the gigantic plane.

The hull & wings were built as separate units & sent off to Long Beach for assembly.

A circa 1940s photo of the flagship of the Hughes “Shady Tree Air Service”,

a surplus Douglas B-23 Dragon bomber (MSN 2746, serial # 39-60, registration NR44890),

most likely taken at Culver City.

This aircraft had been sold to Hughes Aircraft on 5/23/45 for $20,000,

and was eventually destroyed by fire on 10/20/51.

Hughes Airport, as depicted on the 1946 USGS topo map.

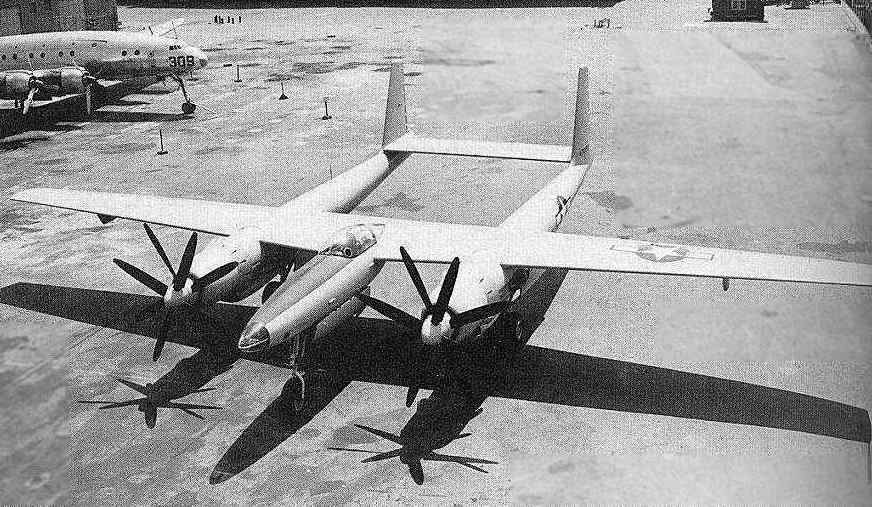

A circa 1946 photo of the 1st prototype of the Hughes XF-11A,

with a Lockheed Constellation in the background.

Shortly after the end of WW2,

Hughes developed the experimental XF-11 twin-engine reconnaissance plane.

It had several radical features, one of which, its contra-rotating propellers, would nearly kill Howard Hughes.

A circa 1940s photo of Howard Hughes in the cockpit of the Hughes XF-11A, the aircraft which would nearly kill him.

The 1st prototype of the Hughes XF-11 takes off from Culver City on 7/7/46 on its ill-fated maiden flight.

Shortly after Howard Hughes took off in the XF-11 prototype from the Culver City runway,

one of the propellers inadvertently went into reverse thrust, sending the craft out of control.

The XF-11 crashed into a house in Beverly Hills, severely injuring Howard Hughes.

The 2nd prototype of the Hughes XF-11 takes off from Culver City on 4/4/47.

It had been fitted with conventional 4-bladed propellers, addressing the 1st prototype's fatal flaw.

This is the earliest photo which shows much of the Hughes Airfield.

A 1947 photo of the rollout of the Hughes HK-1 Hercules flying boat fuselage from Culver City Building 15.

An undated photo of Howard Hughes at the controls of his HK-1 Hercules flying boat.

It was in Long Beach that the Hughes Hercules made its first & only flight in 1947 with Hughes himself at the controls.

Unfortunately, the Hercules project did not result in any production,

as WW2 ended before the aircraft was ready & the government did not see fit to order any examples.

The sole prototype of the HK-1 spent the next 38 years in storage

in a specially-constructed climate-controlled hangar in Long Beach.

A 1943-48 aerial view of the Hughes Airport (from the Alexandria Digital Library @ UC Santa Barbara, courtesy of Jonathan Westerling),

showing the field to have a single northeast/southwest unpaved runway, with a number of buildings along the southeast side of the field.

An undated (circa 1940s?) aerial view looking east along the massive unpaved Hughes runway.

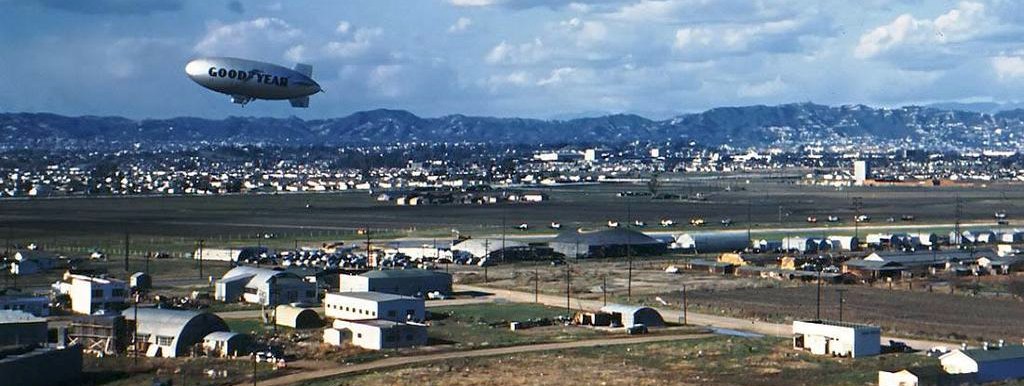

An undated (circa 1940s?) aerial view looking east at the Hughes facility (courtesy of Hughes employee Kurtis Clark),

showing a blimp moored at the ramp, along with a Lockheed Constellation & a dozen military aircraft.

A 1947 aerial view looking west along the massive unpaved Hughes runway, showing the massive Building 15 (where the Hercules had been built).

A total of 6 aircraft were visible on the ramp.

The runway of Hughes Airport was paved in 1948.

The February 1949 LA Sectional Chart continued to depict Hughes Airfield as having a 9,100' unpaved runway.

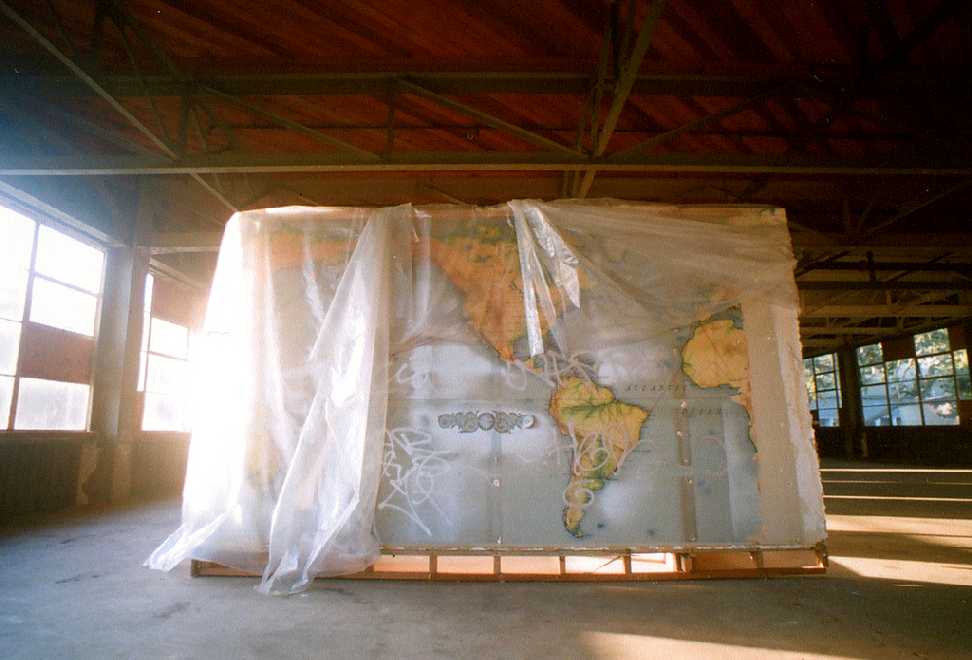

In 1950, frequent Hughes contractor Del Web was brought in to build the 2-story, 37,000-square-foot administration building,

which included Howard Hughes' hardwood clad office.

In an architectural nod to the noted eccentric's fear of hallways,

the offices within the administration building included a bizarre set of doorways

designed to cut through the adjoining suite of offices.

The offices also included a screening room & a wall-sized aeronautical chart depicting the entire world.

The 1950 USGS topo map depicted the single runway, curiously labeled as “Industrial Airport”.

An undated (circa 1950s?) aerial view looking southwest at the Hughes plant, with 4 aircraft parked on the ramp & another on the runway.

A 1952 aerial view looking west at the Hughes Airfield,

with a large number of aircraft on the field.

The Hughes Aircraft Company eventually grew to a total of over 15,000 employees by 1952.

An undated (circa 1950s?) photo looking east (courtesy of Hughes employee Kurtis Clark)

of 2 Lockheed F-94 Starfire fighters (equipped with the Hughes E-1 fire control system & APG-33 radar) on the Culver City ramp.

An undated (circa 1950s?) promotional photo (courtesy of Hughes employee Kurtis Clark)

of Clarence Shoop (head of Hughes Flight Test Division) posing with a Hughes Falcon missile mounted on an F-89 Scorpion, presumably at Culver City.

The Falcon was the world's first mass-produced guided air-to-air missile.

An undated (circa 1950s?) promotional photo (courtesy of Hughes employee Kurtis Clark)

taken on the Hughes Culver City ramp of the components of the Hughes MG-3 fire control system & radar

laid out in front of an F-102 Delta Dagger & a Convair C-131 specially adapted with a radome.

A 4/8/52 photo of the sole prototype of the Canadian Avro Jetliner, parked on the grass at Hughes Culver City.

According to Don Rogers, Avro's Chief Test Pilot for the Jetliner,

it was initially brought to Culver City for possibility of Hughes using it as a testbed for the MG-2 fire control system which Hughes was building for the Avro CF-100 fighter.

Once the jetliner was flown by Howard Hughes, he considered ordering it for airline service with TWA.

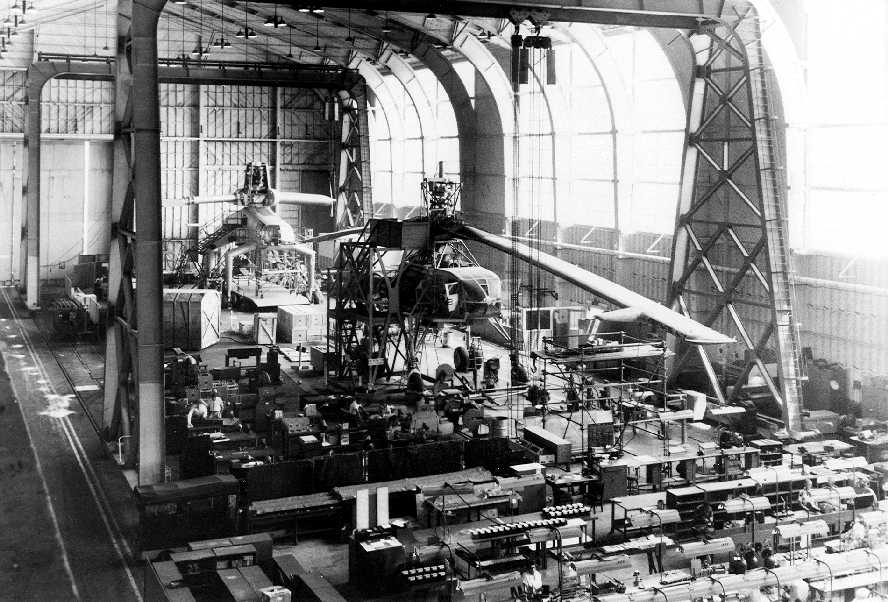

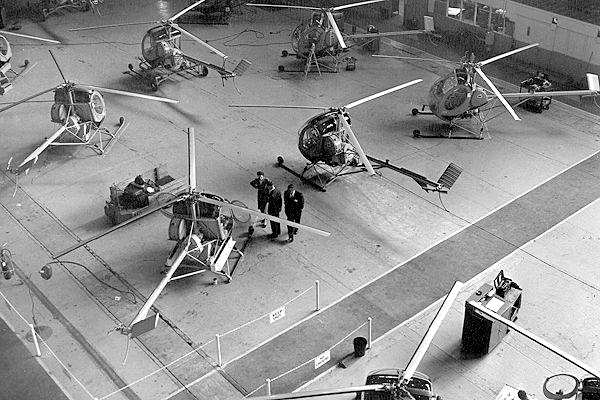

The Hughes company developed & tested a variety of advanced experimental helicopters in the 1950s & 1960s.

The first helicopter built by Hughes was the giant XH-17.

It was a limited flight test design in response to a military proposal

for a helicopter that could air-lift a tank or similar large & heavy loads.

The contract for the XH-17 was originally awarded to Kellett Aircraft in Pennsylvania

but was sold to Hughes in 1948.

As a flying test rig, the XH-17 utilized as many existing parts as possible,

including a cockpit from a Waco CG-15 glider,

landing gear from both a B-25 & C-54, and a bomb-bay fuel tank from a B-29.

A pair of General Electric J35 jet engines were modified

to route bleed air into the 130 foot 2-blade rotor,

where the air was mixed with fuel at the rotor tips in 4 burners.

With the giant rotor turning at only 88 rpm,

the engines & pressure-jets were expected to produce 3,480 hp.

Ground tests of the XH-17 began in December of 1949

and the first flight occurred in October of 1952.

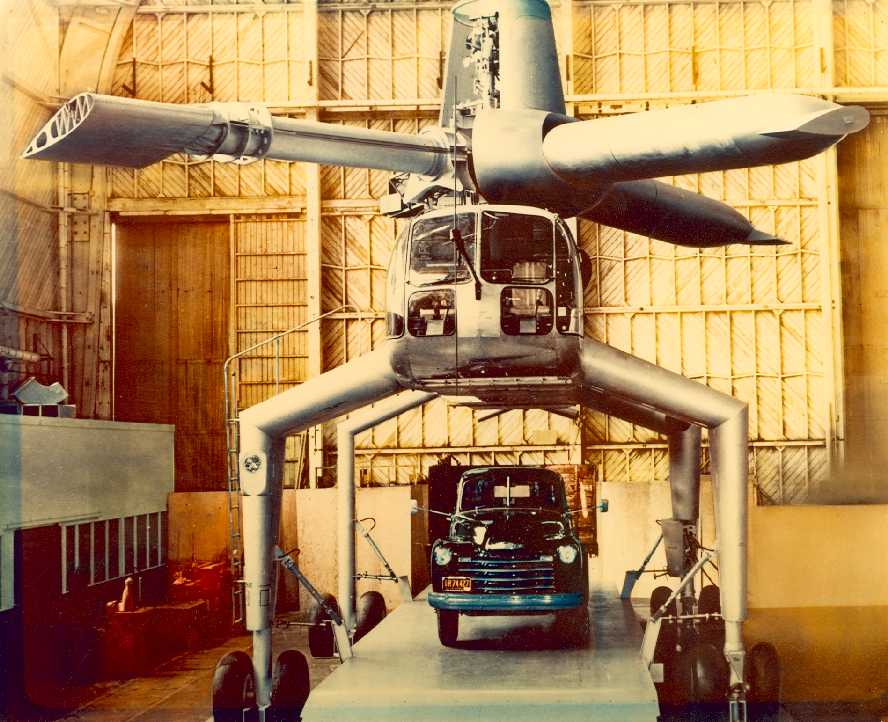

An undated photo (circa 1952-55) of the first helicopter produced by Hughes, the giant XH-17 Flying Crane,

flying above the Culver City runway.

According to John Aldaz, “The XH-17 was only insured for westbound (headwind) flights,

above the Hughes runway, then towed back east to the hangar.

Once, the frustrated test pilot turned it around & flew it back about 150 feet, because there was no wind that day.

He didn't lose his job, but came close.”

Testing of the XH-17 validated the basic design concept, the aircraft having lifted loads of over 10,000 pounds.

Ralph Zucker recalled, “My grandfather owned a few parcels of land around Ballona Creek.

One parcel of land was at the western end of Hughes Airport near Lincoln.

I remember a time when I was around 5 or 6, and going with my dad and grandfather to one of the lots.

The piece of land was adjacent to were Howard kept his XH-17.

My grandfather pointed to what looked like an old metal frame & old aircraft parts, and said that was Howard's helicopter.

I remember that it didn't look like a helicopter to me. I couldn't figure how some could fly such a thing.”

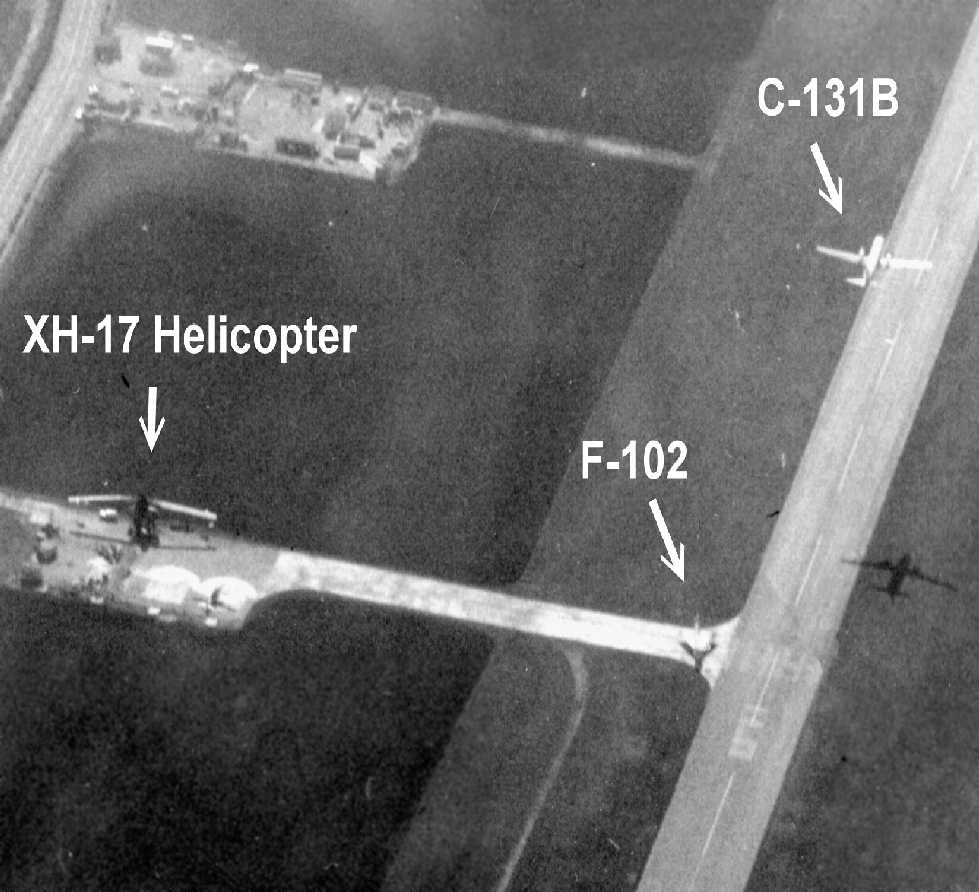

A 1953 aerial view of the Hughes Airport (from the Alexandria Digital Library @ UC Santa Barbara, courtesy of Jonathan Westerling),

showing the paved runway (somewhat shorter than the field's original unpaved runway),

along with a significantly expanded number of hangars & other buildings.

A closeup from the 1953 aerial view, showing an amazing number & variety of military & civilian aircraft parked on the ramp of Hughes Airport.

Note the giant “Hughes” lettering on the Hercules hangar.

A circa 1954-55 photo of the XH-17 prototype & the XH-28 mock-up (in the rear) inside the giant Hughes assembly hall (courtesy of John Aldaz).

The XH-17 tests were judged "somewhat less than successful", (for reasons unknown),

and XH-17 testing was canceled in late 1955.

A circa 1954-55 photo of the full-size mockup of the massive Hughes XH-28 helicopter,

pictured inside the former Spruce Goose assembly hangar at Hughes Culver City (courtesy of John Aldaz),

shown straddling a cargo platform carrying a truck.

One of the most unusual aircraft to be developed by Hughes at Culver City

was the massive XH-28 flying crane helicopter.

The XH-28 was intended to be an enlarged operational follow-on to the XH-17.

Development of the XH-28 was begun in January 1951

to meet an Army requirement for a flying crane capable of transporting

combat-loaded military vehicles weighting up to 20 tons.

Like the XH-17 which was then about to be flown,

the XH-28 was to use a pressure-jet system to drive the 4-bladed main rotor,

with 2 Allison XT40-A-8 turbines being geared to a compressor unit

and compressed air dueled to burners at the tip of each blade.

A circa 1954-55 photo of the full-size mockup of the massive Hughes XH-28 helicopter,

pictured inside the former Spruce Goose assembly hangar at Hughes Culver City (courtesy of John Aldaz),

shown straddling a cargo platform carrying a truck.

Weighing 105,000 pounds fully loaded,

the XH-28 was to have had enclosed accommodation for 2 pilots.

Its 4 tall undercarriage units, each with dual-wheels,

would have given it a spider look while providing adequate clearance for outsize loads.

These loads were to have been either slung beneath the fuselage

or carried on a flat-bed attached between the undercarriage legs

and fitted with a ramp for loading & unloading vehicles.

The XH-28 design was subjected to extensive wind-tunnel tests with various suspended loads,

and a full-scale wooden mock-up was completed inside Hughes' Building 15 (the former Spruce Goose assembly hall) by 1954-55.

In spite of the XH-28's promising capability,

the program was canceled due to cutbacks in the research & development budget made near the end of the Korean War,

and no actual XH-28 aircraft was built.

The September 1954 USAF LA Sectional Aeronautical Chart (courtesy of Chris Kennedy)

depicted Hughes Airport as a private airfield with a 6,800' paved runway & its own control tower.

The 1955 San Diego Sectional Aeronautical Chart (courtesy of John Voss)

depicted Hughes Airport as a private airfield.

It was described as consisting of a single 6,800' foot asphalt runway (9,115' available).

A pre-1959 aerial view looking west along Hughes' Runway 23

(with 1 aircraft on the turnaround pad at the bottom, and another aircraft midway along the runway).

Former Hughes employee Charles Stuart observed, “The hangar 45 (round dome roof) does not appear to be built yet.

Also there appears to be only one ramp to the runway at that location.

It appears that the runway does not go as close to Lincoln Blvd as it does in the next [picture].

The area on both sides of the runway from about midway to the Lincoln Boulevard was planted in lima beans every year for a number of years.

Rumors were that was so the property could qualify for 'agriculture purposes' for tax reasons.”

A March 1959 aerial view looking west at the Hughes runway by Charles Stuart.

Charles recalled, “The pictures were made from a Hughes Company Aero Commander, in support of a missile captive flight program being conducted on an Air Force C-131B aircraft.”

An annotated closeup of the March 1959 aerial view by Charles Stuart.

Charles observed, “The C-131 is just airborne from the runway & the shadow is visible.

Also in the picture is the XH-17 experimental helicopter, which had completed its flight activity.

It sat at that location for a long time - maybe a couple of years after 1959.

There is another aircraft parked beside the helicopter; I can't identify it.

There were a couple of other aircraft that were parked elsewhere & never used for several years (after 1959) that were privately owned by Howard; his execs; or ???

They included a B-25 converted to an executive aircraft - had a large window in the side with venetian blinds.

There was also an AT-6 painted in civilian colors. I heard that one or more belonged to Noah Dietrich, an early associate of Howard Hughes.

These aircraft eventually disappeared & I have no idea what happened to them.

Also in the pictures is a delta-winged aircraft that I am sure is an F-102.

It appears to have just landed & was waiting to taxi down the runway. The wingtips were painted orange.

There were several F-102s there at the time for radar & missile flight testing.”

A series of circa 1960-61 photos (courtesy of Charles Stuart) of a Northrop F-5A Freedom Fighter

conducting demonstration landings & takeoffs on an unpaved surface next to the paved Hughes runway.

Charles Stuart recalled, “Northrop had their own airfield not far away [Hawthorne],

but when they were developing the F-5 they were trying to sell it to countries with unimproved airstrips,

so they ran a lengthy program (demonstration / development) using the grass beside the pavement on the Hughes strip (north side of the paved runway).

They used the dirt strip until it was worn, rough & dusty.

Not sure when this was but probably 1960-61.

The story was (before my time) that Howard was real proud of the grass strip before it was paved

and would 'shut down' the strip if it rained so the sod would not be damaged.

So when this was happening, the grass was real neat when they started these tests

and as you can see, by the time they were finished it was pretty well worn -

my thought at the time was if Howard was still around he would not like that.”

Charles continued, “Hughes used a B-58 (tail # 665 'Snoopy') as a test bed for the weapon system / missile that eventually went into the YF-12.

They flew the B-58 into the Hughes airstrip once to do the modifications on it.

This B-58 had an unusually long nose to accommodate the large radar antenna, which meant on landing there was little or no forward visibility.

The Hughes strip was fairly narrow with a hill on one side, and urban area on the other.

They laid chalk lines in the grass parallel to the runway on each side for the B-58 arrival. Must have worked - all went well.”

An undated (circa 1960s?) aerial view looking west at the Hughes facility (courtesy of Hughes employee Kurtis Clark),

showing a variety of aircraft parked near Building 45, the arch-roof hangar.

An undated (circa 1960s?) aerial view looking east at the Hughes facility (courtesy of Hughes employee Kurtis Clark),

showing a variety of aircraft parked near Building 45, the arch-roof hangar.

A 1962 aerial view of the Hughes Airport (from the Alexandria Digital Library @ UC Santa Barbara, courtesy of Jonathan Westerling),

showing that the paved runway had been extended to the southwest at some point between 1955-62.

Hughes Airport was listed as an active private airfield in the 1962 AOPA Airport Directory,

with an 8,800' paved runway.

The 1964 USGS topo map (courtesy of Kevin Walsh) depicted Hughes Airport as having a single paved northeast/southwest runway.

A 1964 photo by Charles Stuart of Hughes Culver City of an “F-106B with Hangar 45 in the background, view to the west.

The aircraft had completed mods (which included missile launchers under wings) for use on the ARPAT program at White Sands

and was being readied for a maintenance flight.

ARPAT was a ballistic missile defense program, this part an early feasibility experiment to determine if an intercept of a reentry vehicle

can be accomplished without a nuke warhead, in the late stages of the reentry vehicle flight.

ARPA ran the program; a heavily modified Falcon was used [visible under the F-106's wing].

The missile was an XHM-81 (Hughes Missile), a designation they used for missiles that had not been designated by anyone else.

The missile was also called the Experimental ARPAT Interceptor (EAI).

It used a GAR-11/AIM-26 airframe but completely different sensor.

It needed lock-on-before-launch, thus the wing mount requirement for look-up.

The aircraft served as the 'first stage' of an intercept system. The program was successful but further development was terminated by the Ballistic Missile Defense Treaty.

The original aircraft used was a RB-57D, but part way through the program all those models were permanently grounded for wing structural problems.

The F-106 was about only other aircraft capable of the altitude requirements so this one was obtained.

They fired 2 EAI's at each target. I believe they all guided & were considered successful, although they did not carry warheads or proximity detectors, so they all didn't physically impact the targets.”

Pete Mayer recalled, “We used to ride bikes to the bluffs above the airport

and one time flying radio controlled gliders, one got out of control & accidentally landed on the runway by the number 23.

As you can imagine we got ourselves in trouble ‘cause the security police had to retrieve it for us.”

The Hughes XV-9A hot-cycle experimental helicopter,

built & flown at Culver City from 1964-1965.

Hughes was depicted as a private airfield

on the 1965 LA Local Area aeronautical chart (courtesy of John Voss).

The 1966 LA Local Aeronautical Chart depicted Hughes as a private airfield with an 8,800' paved runway & its own control tower.

A 9/13/66 USGS aerial view looking north at the Hughes Airport.

An undated photo of the Hughes Model 269 assembly line in Culver City.

The amazing engineering of the Hughes OH-6 was displayed in April 1966,

when a Hughes OH-6A set a world record (one of 23 world records the OH-6 would eventually set) for the longest nonstop, unrefueled flight by a helicopter.

Bob Ferry, a retired Air Force Lieutenant Colonel & Hughes test pilot, took off from the helipad at the Hughes Tool Company in Culver City

and landed at Ormond Beach, FL, 15 hours & 8 minutes - and 2,213 miles – later.

Ferry had been expected to land in Miami, where the national media were waiting.

But due to weather conditions, he ended up on a deserted beach hundreds of miles north.

The OH-6A had staggered into the air carrying 3 times its empty weight.

More than a ton of the aircraft’s weight was fuel, the rear seat & copilot’s seat having been replaced with auxiliary fuel tanks, requiring Ferry to sit inches from volatile jet fuel.

Helped along by a stiff tailwind, Ferry averaged nearly 150 mph,

at times pushing the Volkswagen-size helicopter to altitudes of more than 24,000 feet, where it shared the sky with airliners.

A CV-7 Buffalo serving as the chase plane carried an official representative of the National Aeronautic Association.

The relatively low speed, good range, and short takeoff and landing distances of the CV-7 made it a good choice to accompany a slow flying helicopter.

“I’m going to run you guys out of gas,” Ferry kidded the crew before takeoff.

And sure enough, the CV-7 was forced to land in Tallahassee to refuel.

The flight was sponsored by the Hughes Tool Company Aircraft Division,

which hoped to beat a record set in 1965 by a twin-engine Sikorsky SH-3A, an aircraft 10 times heavier than the OH-6A.

David Derryberry recalled, “I worked at Hughes Tool Company in Culver City where we were putting 3-5 OH-6As a day out the door for Vietnam.

I worked there in 1966-67 at the age of 18.

I already had my pilots license when I started there & I really enjoyed working there.

In fact as it turned out I was deferred from going into the military when I was called for the draft.

The man at the Selective Service Board said, 'Anyone can shoot a gun, we need you to make helicopters.'

I had no idea that working there would give me a deferment. I just wanted to work for Hughes & be around helicopters.

I got laid-off when the line was moved to Rose Canyon in San Diego. I had the option of moving to SD, but I turned down the offer.

I was 20 years old & it was a stupid decision.

We worked 10-12 hours a day 6 & sometimes 7 days a week to finish 3-5 OH-6As a day.

And that was before the line was moved to San Diego.”

David continued, “It was while I was at Culver City in 1967 that I submitted my drawings

to modify the OH-6A for what became to be known as the NOTAR or No Tail Rotor.

I resubmitted the drawings again while at Hughes Fullerton in 1971.

I have no idea if those drawings were ever used or if they started the engineers thinking, but the Hughes 500 NOTAR is exactly like the drawings I submitted.

I never got any credit for it & no one ever spoke to me about the design after I gave it to my supervisors.”

A 10/13/67 view of mass production of the Army's OH-6A Cayuse observation helicopter in the Hughes Tool Company's historic assembly hall.

A circa 1960s video of the Hughes Culver City OH-6 production facility (courtesy of Liam Aherne).

A 1967 street map depicted Hughes Airport as having a single runway, a taxiway, and 2 buildings.

Lynn Anderson recalled working at Hughes “from 1967 to 1972.

I joined Hughes while finishing up my schooling & worked in Buildings 6 & 12 at various times.

In my era there much of the air operations were the Navy F-111B.

We had 2 of the 4 flyable craft for testing with a Hughes missile system.

They were not very impressive to see since, with the wings extended their take-off speed was low.

They would lift off by the flight line about mid-runway.

It was a sad day at the plant when they announced over the PA system that one of them crashed over the Pacific with a pilot & engineer aboard.”

[That was serial # 151971, the 2nd F-111B prototype, which crashed on 9/11/68.]

Lynn continued, “Much more exciting was a lone [F-4] Phantom. We would know its sound.

The pilot would pull out from the flight line & give it a blast and coast to the east end of Runway 23 (most pilots would just idle).

There he would wait for clearance from LAX & then fire the afterburners making a lot of noise.

Some of us would go out on the balcony of Building 12 to watch.

He would use most of the runway to get up speed, then perhaps 50' above ground,

immediately pulling up the gear & roaring across Lincoln Boulevard.

By the time he got to the lagoon he had enough power to pull the nose up in a steep climb

until the plane would disappear at maybe 30,000' (climbing well over LAX traffic). Very dramatic.”

Lynn continued, “It is good to make a clear distinction of the 2 companies.

When I worked there, the site was shared by both Hughes Aircraft Company (owned by the Hughes Medical Institute of Florida, a non-profit)

and Hughes Tool Company (soon owned by Summa Corporation, Mr Hughes' personal holdings),

maker of helicopters & airborne guns (the Gatling gun type).

The Tool Company was the landlord.”

A Hughes OH-6A Cayuse, one of the thousands of OH-6s built at Culver City.

The Culver City production line for the Army's OH-6A in 1968.

At peak production, over 100 OH-6A's were built per month.

The Hughes Culver City facility eventually became the Hughes Helicopter Company,

where thousands of civil & military helicopters were built,

including the Hughes 300, 500, and OH-6 models.

An undated (circa 1960s-70s) photo of OH-6 under assembly in Culver City.

Ed Fuller recalled, “When I graduated from high school in 1968,

I took a job at Hughes Tool Company in Kearny Mesa, CA as a B-Structural Assembler.

There we built the airframes for the OH-6 Cayuse.

The airframes were then trucked up to Culver City for wiring & final assembly.

Of course, everyone knew WE did the hard part - all they did up there was add accessories. :)

There was also a side area in the plant where they built Model 269 components.”

A 1968 aerial photo from the UCSB Map & Imagery Laboratory

depicted Hughes Airport as having a single paved runway.

Donald Porter recalled, “I started at Hughes Tool Company – Aircraft Division in 1968 (at Building 307 in El Segundo) as a OH-6A technical representative,

then went to Vietnam for a year, and returned to Culver City working in the 500 Program Office tackling all kinds of little problems.”

Willy McLachlan reported that his father (George McLachlan) spent the last 20 years of his career as a pilot at Hughes Aircraft.

According to Willy, “My father reported to work there from 1968-79

as Assistant Manager of the Corporate Flight Operations Department,

both transporting Hughes executives & clients, Hughes engineering & research teams to job & test sites,

and testing various electronic & avionic systems for both fixed-wing & rotary-wing aircraft.”

A 1968 aerial photo looking east along the runway of Hughes Airport (from the LA Public Library).

Notice how undeveloped the surrounding area was, even in 1968.

Hal Ziegler recalled, “I was born in 1962 & lived in an area called Ladera Heights.

Ladera was directly below the final approach to the Hughes Airport.

As a child I became fascinated with aircraft because of all the interesting military aircraft that constantly 'buzzed' our home.

Eventually, I became so intrigued with the Hughes Airport that I would ride my bike there & jump their fence.

Then, I would explore as much as I could until I was discovered (between 1969-72).

A constant military aircraft that 'buzzed' our home during the entire Vietnam war - was an F-4 but it had a bright orange tail.

It made several landings & takeoffs daily for several years.

I could hear it on final & would run outside just to see it & try to get the pilot to wave at me

(it was that low & I could clearly see the pilot).”

By 1970, Hughes had delivered a total 1,434 helicopters to its biggest customer, the U.S. Army.

Aluminum panels were added to the exterior of the massive wooden Cargo Building in 1971.

Brian Ward recalled, “I lived most of my life in Marina del Rey, which is next door.

During the early 1970s, as a spotter/enthusiast I enjoyed seeing the eclectic menagerie of aircraft that would take off & land at the Hughes Airport.

There were no noise restrictions, and the fighter jets could be heard roaring out as far away as Santa Monica, the sound particularly echoing off the Loyola bluffs.

The airport was lighted for night operations, seeing the runway lights & end lights when driving by at night on Lincoln Boulevard,

although it was rare to see an actual night operation.

There was an embarrassing time that a Quantas airliner, bound for LAX lined up mistakenly for Hughes Runway 23

and its pilot finally realized his mistake at about 500', resulting in a go-around.

After that incident, controllers at LAX insisted that all arrivals first line up on the instrument approaches, before being cleared for visual approaches.

I am sure it had happened more than once, since Runway 24R at LAX was only a mile south of the Hughes final approach.”

Mike Davison recalled, “I moved to Westchester when I was a kid in 1971, so I remember when Hughes was in full operation.

I remember riding my bike on the Hughes property along the blufftop & getting chased off by the security guards.

I even remember just north of the railroad tracks & the Hughes property there was one old, white, wood-framed house on the curvy part of Centinela.

I have to assume Mr. Hughes tried to buy the guy out, so he must have been a tough bird to hold out there for so long. I was always wondered about that house.”

A 3/23/71 photo of the 7th & final F-111B prototype, serial # 152715, on the Hughes Culver City ramp.

Note the Hughes 500 helicopter on the right.

Mike Glenn recalled, “I was the maintenance Supervisor on that aircraft when that picture was taken.

I recognize Ed Hudson & Al Mills.”

A March 1971 photo of Charles Stuart in front of “F-111B tail # 715, in front of hangar 45 (view looking south towards Loyola Hill).

It was used for weapon system / Phoenix missile testing after the F-111B was scrapped in favor of the F-14.

Hughes originally had two early models of the F-111B, tail numbers 971 & 972, with 971 being lost.

Number 715 was a later model, and was to have been close to the production configuration.

The F-111s were a sight to see on take off from that relatively close-quarter strip.

They would lift off, then to put the gear up, there was a large 'barn door' that was slanted back with the gear down but had to open wide (near vertical) for the gear to retract.

Until this was completed there was a disconcerting loss of altitude, before the climb was resumed.

In the meantime those big engines were blowing all the dust off the runway (that gear door was actually used as a speed brake in flight).”

Also note the Hughes 500 helicopter just behind the F-111's nose.

A 2/1/72 USGS aerial view of the Hughes Airfield.

A closeup from the 2/1/72 USGS aerial view of the Hughes Airfield, showing just a single aircraft on the field, probably the Hughes corporate Convair 340 N314H.

A 1972 aerial view looking west at the Hughes Airfield, showed a huge number of employee cars, and at least one swept-wing aircraft to the right of the arch-roofed Hangar 45.

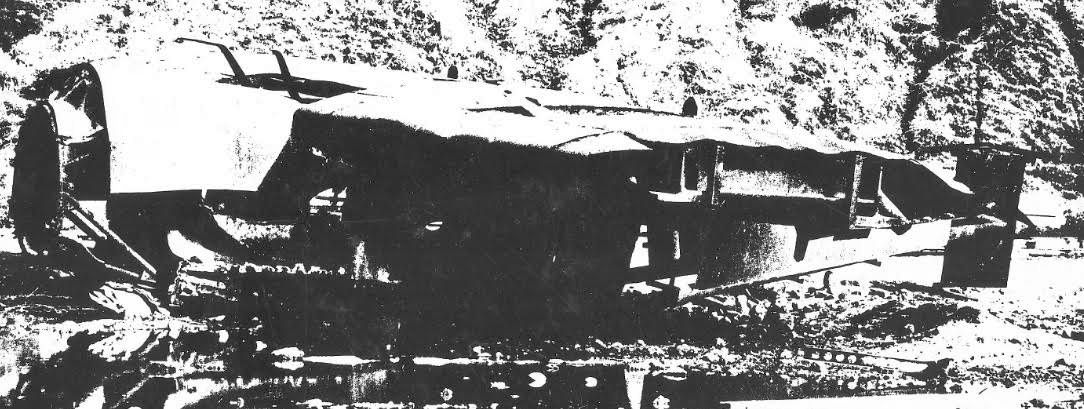

A circa 1973 photo by Ed Weller of what appears to have been the remains of the sole prototype of the enigmatic Hughes D-2, wasting away after 30 years at the Hughes Culver City facility.

Ed recalled, “Back around 1973 my brother & I rode our bicycles past the Hughes Aircraft facility & spotted the [above] framework on the opposite side of Jefferson (North side).

My bother believes the structure reveals it to be a nacelle of Howard Hughes’ D-2 aircraft and… perhaps one from the aircraft that Hughes crashed in?

The framework sat by itself on the edge of a field that didn’t have much else on it.

My brother clearly remembers that the picture was taken at the bottom of the hill & 100+ feet Northeast of the Loyola 'L'.

This explains why the photograph shows hillside in the background.

You can see that the structure was not the same as the H-2 but perhaps a different iteration or prototype of the H-2 that used a different motor.

We recall the wing was covered with metal & therefore maybe related to the XF-11?

My brother points out that there’s a high likelihood that it was from an H-2 type of aircraft since it has radial engine mounting

and the engine mounting is extended a few feet forward of the wing & therefore fairly unique to this one type of aircraft.”

A 1/23/73 photo (courtesy of Hughes pilot George McLachlan) of the Hughes corporate Convair 340 N314H at Culver City.

According to Willy McLachlan, his father (Hughes pilot George McLachlan)

reported that the Convair 340 was “Hughes Aircraft owned & operated.

That aircraft was tail number 324H, and my father regularly flew that plane as part of his duties there.

I often remember from my childhood him referring to 'Three Two Four Hotel'

in conversations about where he was flying, how many he was taking on the trip,

how long he would be gone, and if they were testing any electronics or avionics on the trip.

It often meant he was taking a large group of people, sometimes even Mr. Hughes himself.”

A set of 3 circa 1973-75 photos (courtesy of Hughes pilot George McLachlan) of the sole example of the famous Hughes H-1 Racer,

in which Howard Hughes had set the world speed record in 1935,