Presented by

Wm. Max Miller,

M. A.

Click on Anubis to learn about our logo and banners.

Project Updates

Quickly Access Specific Mummies With Our Or XVII'th XVIII'th

Gallery II

See what's new at the T. R. M. P.

Mummy Locator

View mummies in the

following Galleries:

Dynasty

Dynasty

Including the mummy identified as Queen Hatshepsut.

Gallery III

Including the mummy identified as Queen Tiye.

Gallery

IV

Featuring the controversial KV 55

mummy. Now with a revised reconstruction of ancient events in this perplexing

tomb.

Gallery V

Featuring the mummies of Tutankhamen and his children.

Still in preparation.

XIX'th

Dynasty

Gallery I

Now including the

mummy identified as

Ramesses I.

XX'th

Dynasty

XXI'st

Dynasty

21'st Dynasty Coffins from DB320

Examine the coffins

of 21'st Dynasty Theban Rulers.

Unidentified Mummies

Gallery I

Including the mummy identified as Tutankhamen's mother.

About the Dockets

Inhapi's Tomb

Using this website for research papers

Acknowledgements

Links to Egyptology websites

Biographical Data about William Max Miller

Special Exhibits

The Treasures of Yuya and Tuyu

View

the funerary equipment of Queen Tiye's parents.

Tomb

Raiders of KV 46

How thorough were the robbers who plundered the tomb of

Yuya and Tuyu? How many times was the tomb robbed, and what were the thieves

after? This study of post interment activity in KV 46 provides some answers.

Special KV 55 Section

========

Follow the trail of the missing treasures from mysterious KV 55.

KV

55's Lost Objects: Where Are They Today?

The KV 55 Coffin Basin

and Gold Foil Sheets

KV 55

Gold Foil at the Metropolitan

Mystery of the Missing Mummy Bands

KV

35 Revisited

See rare photographic plates of a great

discovery from Daressy's Fouilles de la Vallee des Rois.

Unknown Man E

Was he really

buried alive?

The

Tomb of Maihirpre

Learn about Victor Loret's

important discovery of this nearly intact tomb in the Valley of the Kings.

Special Section:

Tomb Robbers!

Who were the real tomb raiders?

What beliefs motivated their actions? A new perspective on the ancient practice

of tomb robbing.

Special Section:

Spend a Night

with the Royal Mummies

Read Pierre Loti's eerie account of

his nocturnal visit to the Egyptian Museum's Hall of Mummies.

Special Section:

An

Audience With Amenophis II Journey

once more with Pierre Loti as he explores the shadowy chambers of KV 35 in the

early 1900's.

Most of the images on this website have been

scanned from books, all of which are given explicit credit and, wherever

possible, a link to a dealer where they may be purchased. Some images derive

from other websites. These websites are also acknowledged in writing and by

being given a link, either to the page or file where the images appear, or to

the main page of the source website. Images forwarded to me by individuals who

do not supply the original image source are credited to the sender. All written

material deriving from other sources is explicitly credited to its author.

Feel free to use material from the Theban Royal Mummy Project website.

No prior written permission is required. Just please follow the same guidelines

which I employ when using the works of other researchers, and give the Theban

Royal Mummy Project proper credit on your own papers, articles, or

web pages.

--Thank You

This website is constantly developing and contributions

of data from other researchers are welcomed.

Contact The Theban Royal Mummy Project at:

anubis4_2000@yahoo.com

Background Image: Wall scene from the tomb of Ramesses II (KV 7.) From Karl

Richard Lepsius, Denkmäler (Berlin: 1849-1859.)

XVIII'th Dynasty

Gallery II

Learn about the 18'th

Dynasty here.

Amenhotep I

(c. 1551-1524 B.C.)

18'th

Dynasty

Provenance: DB 320

Discovery Date: 1881

Current Location: National Museum of Egyptian Civilization in Fustat JE 26211;

CG61058

Click here for

biographical data

Details: The mummy of Amenhotep I was discovered in

good condition and has never been unwrapped. It was found with an intact cartonnage funerary mask and had been re-wrapped by 21'st Dynasty restorers in an orange shroud held in place with horizontal and vertical strips of bandaging. Numerous floral garlands had been placed over the shroud and descend almost to the feet of the mummy. Georg Schweinfurth, a professional botanist who examined the floral decorations not long after the mummy's discovery, identified the red, yellow and blue flowers of which the garlands were composed as Delphinium Orientale, Sesbania aegyptiaca, Acacia Nilotica and Carmanthus tinctorius. (Tomashevska, SFG, 13, n. 80.) Tomashevska (citing Partridge) reports that the fragrance of the ancient Delphinium Orientale was still detectable by the scientists who X-rayed the mummy in 1965. (SFG, ibid., n. 81.) A long-dead wasp, which had probably been attracted by this scent, was also

found in the coffin.

X-rays published in 1967 reveal a bead girdle and a

small amulet still within the mummy wrappings. They also show a

post-mortem fracture of the lower right arm, which Reeves thinks probably occurred during the 21'st Dynasty re-wrapping. Although

broken, the kings arms had been placed across his chest in what was to

become the standard position for king's mummies. In 2019, the mummy of Amenhotep I was given a thorough CT scan which revealed many interesting features including the presence of 30 funerary amulets concealed within the wrappings. The detailed report by Sahar Saleem and Zahi Hawass along with the results of this scan may be seen here: Digital Unwrapping of the Mummy of King Amenhotep I (1525–1504 BC) Using CT, (from Frontiers in Medicine, 28'th December, 2021.)

Amenhotep I was found in

a replacement coffin which Reeves thinks was part of the same group of

coffins that Tuthmosis II's replacement coffin came from. It had originally been made

for a mid-18'th Dynasty priest named Djehutymose and was subsequently

re-inscribed by the reburial party for Amenhotep I. The coffin also has

inscriptions supplying other reburial data (see Coffin Docket

translations below.) Reeves, noting the similarity between this replacement coffin and

that of Tuthmosis II, concludes that Tuthmosis II (see

below) may have been reburied a month before Amenhotep I's

restoration occurred. Robert Partridge notes that a beard originally appeared on the coffin's portrait mask and is visible in the photo (shown below left) taken by Emile Brugsch soon after DB320's clearance. Partridge calls attention to the fact that this beard is missing from the portrait mask in the photograph taken by Daressey in 1909. (See photo of coffin

from George Daressy's Cercueils des cachettes royales here.) He also reports that the beard did not appear on the coffin which was on display in the Cairo Museum when he was conducting research for his book (Faces of Pharaohs, 1994.) What happened to the beard remains uncertain. It may have been accidentally broken off while undergoing restoration work between 1881 and 1909 and was never reattached. To view an interactive digital model of the coffin of Amenhotep I, click here. Source Bibliography: ASAE 34 [1934],

47f.; CCR, 7f.; DRN, 212, 253; EM, 91; EMs,

37, ill. 38; FP, 64; MiAE, 79, 89, 91, 122, 157, 208, 315, 316, 318, 322,

323, ills. 88, 265, 266; MMM, 26, 35, 37, 75, 86, 87, ill. 76;

MR, 536f., pl. 4b; RM, 18, pl. XIII; XRA,

1A13-1B8; XRP, 101, 102, 128ff., 131, 132, ill. pp. 18,

32-33.)

Other Burial Data:

Other Burial Data:

Original Burial:

AN B? To read Sjef Willockx’s paper about other possible burial places for Amenhotep I, click here.

Official Inspections: Year 16 of Ramesses

IX'th

Restorations: Year 6 & Year 16 of Smendes

Reburials: (i.) in tomb of Inhapi (WN

A?) by Year 10 of Siamun; (ii.) In DB 320 no earlier than Year 11 of Shoshenq I

(Source Bibliography: DRN,

253.)

Coffin Dockets:

(ii.) "Yr 16 4 prt 11. The

high priest of Amon-Re king of the gods Masaharta

son of king (nsw Pinudjem commanded to renew the burial

(whm krs) of this god by the scribe of the treasury and

scribe of the temple Penamun son of Sutymose (?)" (Source

Bibliography: CCR, 8, pl. 7

[photo][27].)

Photo Credit: Color photos from gettyimages; b&w photo from MR (Cairo, 1889), pl. IV-B .

Source Abbreviation Key

Tuthmosis I

(?) (c. 1524-1518 B.C.?)

18'th Dynasty

Provenance: DB 320

Discovery Date: 1881

Current Location: National Museum of Egyptian Civilization in Fustat CG61065;

JE26217

Click here for biographical

data

Details: The mummy of "Tuthmosis I" had been  thoroughly plundered in antiquity, but his body remained basically

intact except for missing hands. Smith calls attention to the excellent

state of preservation of the mummy and notes the "firmness and durability

of the skin and tissues." The bandages had been soaked in resin, and,

from the condition of the ears, G. E. Smith concluded that they had been

plugged with balls of resin as in the case of Tuthmosis II and Tuthmosis III (see entries for both mummies below.)

Smith remarked that the mummy's genitalia had been treated in an unusual

manner, having been somehow flattened against the perineum and thereby

giving the erroneous impression that the man had been castrated. This may

have resulted from over-desiccation during the embalming process. Maspero

noted that the mummy's teeth were worn, and believed the man was over

fifty at the time of his death.

thoroughly plundered in antiquity, but his body remained basically

intact except for missing hands. Smith calls attention to the excellent

state of preservation of the mummy and notes the "firmness and durability

of the skin and tissues." The bandages had been soaked in resin, and,

from the condition of the ears, G. E. Smith concluded that they had been

plugged with balls of resin as in the case of Tuthmosis II and Tuthmosis III (see entries for both mummies below.)

Smith remarked that the mummy's genitalia had been treated in an unusual

manner, having been somehow flattened against the perineum and thereby

giving the erroneous impression that the man had been castrated. This may

have resulted from over-desiccation during the embalming process. Maspero

noted that the mummy's teeth were worn, and believed the man was over

fifty at the time of his death.

The mummy was found in coffins (CG 61025) originally made

for Tuthmosis I by Tuthmosis III (see Herbert Winlock, JEA 15,

[1929], 59, n. 3.) Winlock had observed that the the outer coffin

would "fit snugly" into the KV 38 sarcophagus (JEA 15,

ibid.) Reeves notes textual similarities between inscriptions on

the inner coffin and the KV 38 sarcophagus lid (DRN, 18, n.

51.) The coffins had been appropriated, redecorated, and

reinscribed by Pinudjem I for his own use (see photo of coffins from CCR [Cairo,

1909.]) Reeves, after considering the size of the appropriated

coffins, believes that Tuthmosis I also originally had a third,

inner

coffin which is now lost, and that this coffin might have been similar to

that in which Tutankhamen was found (DRN, 18, n.

50.)

Since there were no dockets on the

bandages or coffins, the identification of this mummy is still a matter of

dispute. Maspero believed it to be the body of Tuthmosis I because (to

him) the head bore a "striking resemblance" to those of Tuthmosis II and

Tuthmosis III. Smith gave further support to this identification by

concluding that the technique of embalming employed dates the mummy to a

period later than Amosis and earlier than Tuthmosis II. However,

prevailing opinion currently denies that the body is that of Tuthmosis I

because of the position of the arms, which are not crossed over the chest

as on all pharaoh's after Amenhotep I. One recent theory, as noted by Ikram and

Dodson, proposes that this mummy is actually that of Ahmose-Sipairi,

the alleged father of Tuthmosis I. (For more on identifying royal mummies,

read Edward F. Wente's article, Who Was Who Among the Royal Mummies. ; Dennis Forbes' Royal Mummies Musical Chairs ; and Dylan Bickerstaffe's

The Royal Mummies of Ancient Egypt.) (Source Bibliography: DRN, 17f., 203, 244; EM,

91; EMs, 37, ill. 38; EMbm, 53; JEA 15,

[1929], 59, n. 3.)

Other Burial Data:

Original

Burial: The original tomb of Tuthmosis I is still not known with

certainty. Since two tombs (KV 38 and KV 20) and two sarcophagi (one from each tomb) are

associated with this king, the circumstances surrounding his burial are

far from clear. Loret, who discovered KV 38 in 1899, believed that this

was the tomb of Tuthmosis I

referred to by the architect Ineni, who

described on the walls of his own tomb how he had secretly designed the

king's sepulcher, "no one seeing, no one hearing." (Learn about Ineni's

tomb at Ian Bolton's Egypt: Land of Eternity website.) KV 38

obviously had been connected to Tuthmosis I, as evidenced by the presence

of an empty sarcophagus (RS, 52ff.) and canopic chest

inscribed for this king. However, in 1903, Howard Carter excavated KV 20

and discovered another sarcophagus inscribed for Tuthmosis I along with a

sarcophagus belonging to Hatshepsut (ASAE 6 [1906], 119.) The

question arose concerning which of the two tombs associated with this king

was the the original place of his burial. After studying the architectural

design of KV 38, John Romer dated it to a time no earlier than the reign

of Tuthmosis III (JEA 60 [1974], 121f.) Proponents of

Romer's dating scheme therefore point to KV 20, known to be the tomb of

Hatshepsut, as the original tomb of Tuthmosis I. They argue that Queen

Hatshepsut wished to be buried with her father and had his tomb modified

to accommodate her own burial. Tuthmosis III, wishing to erase

Hatshepsut's memory, subsequently prepared KV 38 (complete with a

new sarcophagus) for Tuthmosis I, and had the king removed from the dead

queen's offensive presence and reburied in the the newer tomb (DRN,

18.) Proponents of Loret's initial appraisal of KV 38 as the

original resting place of Tuthmosis I contend that Hatshepsut had KV 20

prepared for herself and then removed her father's mummy from KV 38 into

this tomb. Tuthmosis III subsequently restored Tuthmosis I to his original

tomb, where a new sarcophagus awaited him (cf. Herbert Winlock in

JEA 15 [1929], 56ff.; and Hayes, RS, 6ff.)

Both theories account nicely for the existence of two sarcophagi for

Tuthmosis I, but the correctness of either is still very much an open

question. (Source Bibliography: ASAE 6 [1906],

119; DRN, 17f.; JEA 60 [1974], 119ff; see

especially George B. Johnson in KMT, [3:4], 64-81; RS, 6ff.,

52ff.)

Reburials: (i.) By Hatshepsut in KV 20? By

Tuthmosis III in KV 38? (ii.) in tomb of Inhapi (WN A?) during Year 7-8 of

Psusennes I;

and (iii.) in DB 320 after year 11 of Shoshenq I.

(Source Bibliography: DRN, 244.)

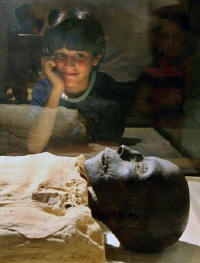

Photo Credits: Top photo from AFP/Getty Images; black & white photo from RM (Cairo, 1912,) pl. XX; color photo of young visitor to the Royal Mummy Room smiling at the mummy currently identified as Tuthmosis I by Amr Nabil/AP Photo. For high resolution images of Tuthmosis I see the University of Chicago's Electronic Open Stacks copy of Smith's The Royal Mummies (Cairo, 1912) Call #: DT57.C2 vol59. plates XX, XXI, XXII. A beautiful color closeup portrait of the mummy of Tuthmosis I (from AFP/Getty Images) may be seen here.

Tuthmosis

II (c. 1518-1504 B.C.)

18'th

Dynasty

Provenance: DB 320

Discovery Date: 1881

Current Location: National Museum of Egyptian Civilization in Fustat CG61066;

JE26212

Click here for biographical data

Details: The mummy of Tuthmosis II was

unwrapped by Gaston Maspero on July 1'st, 1886. It had been severely

damaged in antiquity and was restored by G. E. Smith on September 22,

1906. Smith chronicles the history of injuries that this mummy sustained

at the hands of thieves: the right leg was severed from the body; the

abdominal wall was broken away; ribs were badly broken; the right arm was

cut off just below the elbow; the left arm was broken off at the shoulder,

and the neck and face had been cut in several places with a sharp

instrument.

Tuthmosis II's fingernails and

toenails had been neatly trimmed. His ears and nostrils had been plugged

with linen soaked in resin, and remains of the embalming wound (which had

been mostly obliterated when the abdominal wall was hacked away) indicated

that it had been fusiform, large and gaping. Although Maspero reported the

presence of the king's genitals when he unwrapped the mummy in 1886, Smith

could find no definite remains of them when he examined the mummy twenty

years later. He comments that they may originally have been flattened out

and pressed against the perineum as in the case of the alleged mummy of

Tuthmosis I above.

Maspero believed that

Tuthmosis II died young, at around age 30. He based his conclusion on the

condition of the king's teeth, which were not badly worn. However, Smith

pointed out that the ruler's overbite (a well-known characteristic of the

Tuthmosids) could have effected dental wearing and therefore concluded

that Maspero's dentally based age estimate was doubtful. Smith noted that

Tuthmosis II was practically bald and that the skin of his face was

wrinkled, facts which made him conclude that the king was older than 30

when he died. No obvious cause of death was found during the examination

of the mummy, but Maspero, Smith, Ikram and Dodson all report that

the ruler's skin is covered with scab-like patches that may be symptomatic

of some as-yet unknown disease which may have claimed his life. Smith,

however, thought that the skin eruptions could have been caused post

mortem by reactions of the tissues with the embalming

materials.

Maspero believed that

Tuthmosis II died young, at around age 30. He based his conclusion on the

condition of the king's teeth, which were not badly worn. However, Smith

pointed out that the ruler's overbite (a well-known characteristic of the

Tuthmosids) could have effected dental wearing and therefore concluded

that Maspero's dentally based age estimate was doubtful. Smith noted that

Tuthmosis II was practically bald and that the skin of his face was

wrinkled, facts which made him conclude that the king was older than 30

when he died. No obvious cause of death was found during the examination

of the mummy, but Maspero, Smith, Ikram and Dodson all report that

the ruler's skin is covered with scab-like patches that may be symptomatic

of some as-yet unknown disease which may have claimed his life. Smith,

however, thought that the skin eruptions could have been caused post

mortem by reactions of the tissues with the embalming

materials.

The mummy was equipped with a floral

garland, and an outer shroud covered the remains of the original

wrappings. The shroud had a 21'st Dynasty inscription which dates the

reburial of Tuthmosis II to Year 6 3 prt 7 of Smendes/Pinudjem I

(see Linen Docket translation below.) Tuthmosis II was found in a

coffin originally belonging to an unidentified man, also of the 18'th

Dynasty. (See photo of coffin below from George Daressy's Curlicues des cachettes royales, pl. XIII.) (Source

Bibliography: CCR, 18; DRN, 203, 209; EM, 91;

EMs, 37, ill. 38; MiAE, 28, 88, 255, 258, 315, 318, 322,

323, ill. 355; MMM, 35, 37, 87, 88; MR, 545ff.; RM,

28ff.; XRA, 1C7-1D3; XRP, 101, 133, 136, 137, ill.

36.)

Other Burial Data:

Original Burial:

Unknown. KV 42? WN-A? or DB 358?

George B. Johnson, in a paper appearing in KMT ([10:

3] 20-33, 84-85) presents a careful consideration of the

theories that KV 42 is the tomb of Tuthmosis II. The tomb was first

attributed to this king by Arthur Weigall in 1910 (GAE,

224-225.) William C. Hayes, after his study of sarcophagi and

architectural tomb development in the Valley of the Kings, wrote in 1935

that KV 42 was probably a tomb of Tuthmosis II that had never been used

(RS, 2, pl. II; 34, 36f., 141.) Most recently (in

1990) Erik Hornung also attributed the tomb to Tuthmosis II. (HE,

204.)

KV 42, which is located in the

south-western end of the Valley of the Kings, may have been discovered by

the workmen of Victor Loret in 1898-1899 (see Johnson, KMT

[10: 3] 20). If so, Loret never reported the

tomb, and, in 1900, Boutros Andraos and Chinouda Macarios (after receiving

permission from Howard Carter to excavate in the Valley) claimed the

discovery of KV 42 for themselves (ASAE II [1901], 196-198.)

The tomb had a cartouche shaped burial chamber and royal proportions, and

architecturally seemed part of the series of tombs beginning with the tomb

of Tuthmosis

I (KV38) and ending with the tomb of Tuthmosis III (KV34.) Howard Carter inspected the tomb and discovered

canopic jars inscribed for Senetnay, the wife of Sennefer, who was a mayor

of Thebes during the reign of Amenhotep II. Based on their presence, Carter

tentatively suggested that KV 42 might be Sennefer's tomb (ASAE II

[1901], 196-198. cf. T. G. H. James, HCPT, 76.)

Twenty years after his first inspection, Carter discovered the foundation

deposits of Meryt-Re Hatshepsut near the entrance to KV 42, and cautiously

concluded that the tomb had been prepared for her. Still influenced by the

discovery of Senetnay's canopic jars in the tomb, Carter now proposed that

Sennefer had appropriated the tomb from Meryt-Re Hatshepsut (ToT,

[vol. I], 84.)

tentatively suggested that KV 42 might be Sennefer's tomb (ASAE II

[1901], 196-198. cf. T. G. H. James, HCPT, 76.)

Twenty years after his first inspection, Carter discovered the foundation

deposits of Meryt-Re Hatshepsut near the entrance to KV 42, and cautiously

concluded that the tomb had been prepared for her. Still influenced by the

discovery of Senetnay's canopic jars in the tomb, Carter now proposed that

Sennefer had appropriated the tomb from Meryt-Re Hatshepsut (ToT,

[vol. I], 84.)

Elizabeth Thomas also

rejected the idea that KV 42 was the tomb of Tuthmosis II. Persuaded by

the evidence of Meryt-Re Hatshepsut's foundation deposits and the

cartouche shaped burial chamber, she suggested that KV 42 was a royal tomb

dedicated by Meryt-Re Hatshepsut for the use of one of her sons or

grandsons (RNT, 70-80.) The theory that KV 42 was the tomb

of Meryt-Re Hatshepsut is the one currently accepted by most Egyptologists

including Romer (TVK, 253), Wilkinson & Reeves

(CVK, 103) and Roehrig (KMT [10: 3],

27 and n. 17.)

Based on his analysis of the

kheker frieze in the burial chamber, George B. Johnson presents

persuasive evidence that KV 42 post-dates the death of Tuthmosis II

by many years. This frieze is stylistically different from kheker

decorations in other 18'th Dynasty royal tombs, and is virtually

identical to the kheker frieze from the Dier el-Bahri chapel of

Tuthmosis III, to such an extant that Johnson believes they could have

been painted by the same artist (KMT [10: 3], 28f.,

31.) On still other stylistic grounds, Johnson dates the rectangular

quartzite sarcophagus found in the burial chamber of KV 42 to the reign of

Tuthmosis III, and confidently attributes the ownership of the tomb to

Meryt-Re Hatshepsut (KMT [10: 3], 84.) Sarcophagus

specialist Edwin C. Brock also finds no evidence indicating that KV 42

belonged to anyone other than Meryt-Re Hatshepsut (KMT [10:

3], 33 [sidebar.]) If KV 42 is not the

tomb of Tuthmosis II, then where was the original burial of this king?

According to Reeves the recent proposal of WN-An lacks solid evidence in

favor of the claim that this is the missing tomb of Tuthmosis II

(DRN, 18, 24, 253-54). Johnson mentions an

inscription on a statue of a certain Hapuseneb, now in the Louvre, which

records the intriguing fact that Tuthmosis II had commissioned this vizier

and high priest of Amen to "conduct the work upon his cliff tomb because

of the great excellence of my plans." (KMT [10: 3],

84.) The lost tomb of Tuthmosis II, described here as a "cliff tomb,"

may be similar in placement to the original tomb of his wife, Hatshepsut,

before she became king. A tomb associated with Tuthmosis II that matches this description is as yet undiscovered.

If KV 42 is not the

tomb of Tuthmosis II, then where was the original burial of this king?

According to Reeves the recent proposal of WN-An lacks solid evidence in

favor of the claim that this is the missing tomb of Tuthmosis II

(DRN, 18, 24, 253-54). Johnson mentions an

inscription on a statue of a certain Hapuseneb, now in the Louvre, which

records the intriguing fact that Tuthmosis II had commissioned this vizier

and high priest of Amen to "conduct the work upon his cliff tomb because

of the great excellence of my plans." (KMT [10: 3],

84.) The lost tomb of Tuthmosis II, described here as a "cliff tomb,"

may be similar in placement to the original tomb of his wife, Hatshepsut,

before she became king. A tomb associated with Tuthmosis II that matches this description is as yet undiscovered.

Restoration or Reburial in new

tomb (evidence is unclear): Year 6 of Smendes/Pinudjem I. At this time,

Tuthmosis II was given a new coffin and

re-wrapped.

Reburial: (i) Possibly in tomb of Inhapi (WN

A?) along with Amenhotep I, in Year 6 of Smendes/Pinudjem I.; and

(ii) in DB 320 after Year 11 of Shoshenq I..

(Source Bibliography: ARE, 161-162; ASAE II [1901]

196-198; CVK, 103; DRN, 18, 24, 253-54; GAE,

224-225); HCPT, 76; HE, 204; KMT ([10: 3] 20-33, 84-85; RNT, 70-80.)

Linen Docket:

"Yr 6 3 prt 7 Smendes/Pinudjem I, 'On this day the

high priest of Amon Re king of the gods Pinudjem son of the high priest of

Amun Piankh commanded the overseer of the great double

treasury Payneferher to repeat the burial (whm sm3)

(rebury?) king (nsw) Aaenre (sic.) l. p.

h.'"(Source Bibliography: DRN, 234, no. 13; GPI doc.

2; MR 545 f. [facs., transcr.]; RNT, 249

[4a]; TIP, 418 [9].)

Photo Credit: Color photos from Patrick Landmann/ACI; B&W photo of Tuthmosis II's mummy from RM (Cairo, 1912,) pl.

XXIII; photo of coffin from CCR, pl. XIII. For high resolution images of Tuthmosis II see

the University of Chicago's Electronic Open Stacks copy of Smith's

The Royal Mummies (Cairo, 1912) Call #: DT57.C2

vol59. plates XXIII, XXIV.

Hatshepsut? (c.1473-1458

B.C.)

See

more color images of

the KV 60 mummy. Details: KV 60, the tomb in which

the mummy above was found, was discovered by Howard Carter in 1903 near

the entrance to the tomb of 20'th Dynasty Prince Montuherkopeshef (KV 19.) Carter entered the tomb but never had it

cleared, probably because it did not contain the kind of treasures in

which Theodore Davis, who was funding Carter's work at the time, took

interest. After resealing the tomb, Carter more or less abandoned his

discovery, and only wrote a brief report about the tomb in which he noted

the presence of two mummies left in the burial chamber. Both mummies were

of females, and one was contained in a coffin trough (Cairo Museum Temp.

Reg. # 24/11/16/1) bearing the inscription: "sdt nfrw nsw in

m3ct hrw." Carter and Percy Newberry (who was also

present when the tomb was entered) thought the In named in the inscription

was one of the nurses of Tuthmosis IV. H. W. Helch and Elizabeth Thomas,

however, identified In as Sitre, who also bore the name In and was one of

the nurses of Hatshepsut. Other Burial Data: Tuthmosis III (c.

1504-1450 B.C.)

18'th Dynasty

Provenance:

KV 60

Original Discovery Date: 1903 by

Howard Carter

Rediscovery: June 27-July 4, 1989, by Donald P.

Ryan

Current Location: Left in a protective box

in KV 60 since its rediscovery by Donald P. Ryan in 1989, this mummy was moved

to the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities in Cairo in order to facilitate its examination.

It was relocated to the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization in Fustat on April 3, 2021.

Biographical data on Hatshepsut: click here

Three years

after Carter's discovery, Edward Ayrton entered KV 60 and removed the

mummy in the coffin for shipment to Cairo, but conducted no further work

in the tomb. Since neither Carter or Ayrton had drawn maps indicating the

exact location of the tomb, the whereabouts of KV 60 and its remaining

occupant became forgotten.

On June 27'th, 1989,

Egyptologist Donald P. Ryan rediscovered the lost KV 60 after a search

that only lasted 20-30 minutes! After systematically clearing the pit in

which a steep flight of steps led downward into the tomb, Ryan finally

entered KV 60 on July 4'th. The tomb had been thoroughly pillaged in

antiquity. Ryan and E. A. O. inspector Mohamed el Bialy had to step

cautiously over wooden coffin fragments, mummy wrappings, and pieces of

broken pottery which were scattered about the entrance corridor. They

reached the undecorated burial chamber (a room measuring approximately 5.5

by 6.5 meters and 2.0 meters in height) and saw the mummy of the unknown

woman left by Carter and Ayrton in the middle of the floor. (At right: Dr. Ryan's color photo of the mummy as found on the floor of KV60.)

On June 27'th, 1989,

Egyptologist Donald P. Ryan rediscovered the lost KV 60 after a search

that only lasted 20-30 minutes! After systematically clearing the pit in

which a steep flight of steps led downward into the tomb, Ryan finally

entered KV 60 on July 4'th. The tomb had been thoroughly pillaged in

antiquity. Ryan and E. A. O. inspector Mohamed el Bialy had to step

cautiously over wooden coffin fragments, mummy wrappings, and pieces of

broken pottery which were scattered about the entrance corridor. They

reached the undecorated burial chamber (a room measuring approximately 5.5

by 6.5 meters and 2.0 meters in height) and saw the mummy of the unknown

woman left by Carter and Ayrton in the middle of the floor. (At right: Dr. Ryan's color photo of the mummy as found on the floor of KV60.)

The mummy was that of an obese older woman

approximately 1.55 meters tall. Egyptologist/coroner Mark Papworth, who

examined the body, found the teeth to be well worn and noted that the

embalming wound was located in the pelvic floor rather than in the side,

this unusual position probably being necessitated by the woman's

corpulence (cf. the mummy of 21'st Dynasty High Priest Masaharta.) Ryan described the mummy as

being mostly unwrapped and excellently preserved. He noted that some

strands of reddish-blonde hair lay on the floor beneath the mummy's head.

Whether the color of the hair was natural or the result of reactions

with the embalming materials is currently unknown to me. Ryan described

the mummy's head as bald. It is possible that the hair fell out post

mortem, perhaps as the result of the bandages being roughly removed by

thieves. The hair could also conceivably be the remains of a wig worn by

the woman in life or later placed on her head by the

embalmers.

Although no inscriptions were found

which could help identify the woman, her burial in the Valley of the Kings

attested to the high social position she once held. She was found with the

remains of what had once been an expensive, high-status burial. Ryan

discovered a fragment of a coffin face-piece in a niche in the entry

corridor which was disfigured by adze-marks, indicating that it had once

been covered with thick gold foil that had been greedily hacked off by

thieves. In the burial chamber, across from the entrance, lay a pile of

the mummified food offerings associated with wealthy burials. Most

significantly, the mummy's arms are positioned in a "royal pose" similar

to that found on the mummy of Queen Tiye from KV 35: the left arm is crossed over the chest with the

left hand clenched, thumb extended, fingernails painted red and outlined

in black; the right arm is extended along the right side of the body with

the hand unclenched and the fingers extended.

Confidently dated to the 18'th Dynasty, found in the Valley of the Kings

with the remnants of an expensive burial, and accompanied by the mummy of

Hatshepsut's nurse Sitre, the KV 60 mummy with its regally positioned arms

caused researchers to wonder if it could be the mummy of Hatshepsut

herself, cached in KV 60 after necropolis officials discovered that her

original tomb, near-by KV 20, had been disturbed by thieves. Ryan noted that

the reverse side of the fragmentary coffin face-piece found in the wall

niche had a notch at the chin which could have been used to hold a false

beard. He made the highly relevant observation that only one18'th Dynasty

female, sufficiently important to merit a burial in the Royal Valley, wore

a false beard: the female king, Hatshepsut-Maatkare.

Confidently dated to the 18'th Dynasty, found in the Valley of the Kings

with the remnants of an expensive burial, and accompanied by the mummy of

Hatshepsut's nurse Sitre, the KV 60 mummy with its regally positioned arms

caused researchers to wonder if it could be the mummy of Hatshepsut

herself, cached in KV 60 after necropolis officials discovered that her

original tomb, near-by KV 20, had been disturbed by thieves. Ryan noted that

the reverse side of the fragmentary coffin face-piece found in the wall

niche had a notch at the chin which could have been used to hold a false

beard. He made the highly relevant observation that only one18'th Dynasty

female, sufficiently important to merit a burial in the Royal Valley, wore

a false beard: the female king, Hatshepsut-Maatkare.

In 2007, Dr. Zahi Hawass, at that time the Secretary

General of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, announced that

the KV 60 mummy had been identified as Hatshepsut. A molar

attributed to Hatshepsut had been found in a box inscribed for the famous

18'th dynasty female ruler in the DB 320 cache. (At left: box inscribed for Hatshepsut containing the remains of a human liver and a molar assumed to be the female Pharaoh's.) When Hawass examined the

KV60 mummy, he noticed that it was missing a molar. Subsequent dental

examinations revealed that the Hatshepsut molar from the DB 320 box fit

into the gap in the jaw of the KV 60 mummy. Based on this

dental match, Hawass confidently announced that the mummy of Hatshepsut

had finally been identified.

Other more cautious investigators await the confirmation of DNA testing

before unreservedly accepting this identification. For an interesting account of the various views concerning the identification of the KV60 mummy as Hatshepsut, click here for Caroline Seawright's paper The Process of Identification: Can Mummy KV60-A be Positively Identified as Hatshepsut?

(Source Bibliography: ASAE 4 [1903], 176f.; DEM,

67; DRN, 139, 157, 201, 244-245; Donald Ryan in

KMT [1:1], 34-39, 58-59, 63; RNT,

137.)

Original

Burial: KV 20?

Photo

Credit: Top photo: gettyimages; photo of KV60-A in situ: Donald P. Ryan; photo of DB320 Hatshepsut box: Egyptology.persian.

18'th Dynasty

Provenance: DB 320

Discovery Date: 1881

Current Location: National Museum of Egyptian Civilization in Fustat CG61068;

JE26213

Click here for biographical data

Details: The mummy of Tuthmosis III was unwrapped by

Emile Brugsch in July of 1881 and then subsequently rebandaged, only to be

unwrapped a second time in 1886. Maspero records in Les Momies Royales

that the mummy was covered with a greasy, whitish layer of material

containing putrid human fat. Originally thought to be natron by Dr.

Mathey, G. E. Smith identified this substance as an "efflorescence

of fatty acids."

The mummy had been badly

damaged in antiquity and "repaired" by members of the reburial party, who

reinforced it with four wooden oars (see photo of wrapped mummy from

MR1 [Cairo, 1881].) The head was broken off at

the neck; the arms and legs were detached; both arms were broken at the

elbows, and the feet were broken off. The right arm and forearm were tied

to a piece of wood by a mass of fine linen. The king's left hand is

clenched, indicating that he had once been holding an object (perhaps a

ceremonial scepter or flail) which robbers had

stolen.

The 11 cm. embalmer's incision on the left

side cuts a diagonal line from hip bone to pubes, and Smith records that

through its narrow aperture one can see the resin soaked linen used to

fill the body cavity after the internal organs had been removed. Resin

treated wads of linen had also been used to plug up the nostrils. Unable

to find any traces of the genitals, Smith believed that they had been

removed, probably during the embalming process. Tuthmosis III was

short, standing only 1.5 m (just over 5 ft.) in height, and, since no sign

of hair remained on the scalp, Smith concluded that he had been completely

bald. Smith especially notes the skull, which he describes as "very

remarkable for it's large capacity [and] pentagonoid form." As in the case

of the mummy of Tuthmosis II (cf. above), large portions of Tuthmosis

III'rd's skin were covered with what appears to be a rash of some sort,

perhaps caused by an illness or by the action of the embalming salts, oils

and resins on the skin after death.

Strings of

beads, made variously of carnelian, gold, lapis lazuli, and green felspar

were found on the shoulders lying upon the innermost bandages. (Reeves

states that the beads were found beneath the innermost bandages,

but Smith quite clearly says that they were not touching the mummy's skin

and found on top of the innermost layer of wrappings.) A bracelet on the

right arm was also revealed much later by X-rays. Tuthmosis III was found

in his original coffin (Cairo Museum CG 61014) which Reeves thinks

might have been the second innermost coffin of a nested set. All the

surfaces of this coffin have been adzed over and the eye inlays removed.

However, the inscriptions on the interior of the coffin remain intact. (See photo of coffin from CCR [Cairo, 1909] pl.

14.)

Strings of

beads, made variously of carnelian, gold, lapis lazuli, and green felspar

were found on the shoulders lying upon the innermost bandages. (Reeves

states that the beads were found beneath the innermost bandages,

but Smith quite clearly says that they were not touching the mummy's skin

and found on top of the innermost layer of wrappings.) A bracelet on the

right arm was also revealed much later by X-rays. Tuthmosis III was found

in his original coffin (Cairo Museum CG 61014) which Reeves thinks

might have been the second innermost coffin of a nested set. All the

surfaces of this coffin have been adzed over and the eye inlays removed.

However, the inscriptions on the interior of the coffin remain intact. (See photo of coffin from CCR [Cairo, 1909] pl.

14.)

As a matter of interest, a fragment of the shroud from Tuthomosis III’s mummy managed to find its way into the collection of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. The museum’s website states that the small shroud section had been loaned to them by an individual named Horace L. Mayer in 1931. Mayer finally donated the piece to the institution in 1960 and it was recorded as Accession Number 60.1472. The museum’s website further states that the shroud fragment had previously been part of the collection of Clemente Maraini, and indicates that Adolf Erman, the famous German Egyptologist, had in some fashion been involved with Maraini and the fragment. The provenance data provided on the web page mentions a letter written by Erman to Maraini in 1885, just four years after DB320’s official discovery. No information concerning the contents of this letter is given on the MFA webpage.

A brief 1931 report published by Dows Dunham entitled “A Fragment from The Mummy Wrappings of Tuthmosis III,” (JEA 17, 209-210) supplies information about Adolf Erman’s correspondence with Maraini. Dunham reports that Maraini acquired the shroud fragment “some time prior to 1885," when he sent a photograph of it to the Berlin Museum along with a request for further data. Erman (who never saw the actual fragment and only examined the photograph Maraini had sent) wrote back and informed Maraini that the fragment came from the recently discovered DB320 cache tomb and had been part of the shroud of the illustrious Tuthmosis III. He also “spoke of its value for the study of the religious texts because of its early and exact dating.” (JEA 17, ibid.) Dunham also states that the fragment had not gone directly from Maraini to Horace L. Mayer. According to Dunham, an individual named Vassalli Bey had acquired the shroud fragment from Maraini prior to its acquisition by Mayer, and states that Mayer obtained the fragment around 1928 from Vassalli Bey’s heirs. (JEA 17, ibid.) In the 1908 edition of the Guide to the Cairo Museum Gaston Maspero refers to a man named Vassalli Bey who had once been a conservator working in conjunction with Emile Brugsch at the Bulaq Museum (GCM, 103f.) This individual was better known as Luigi Vassalli, an Egyptologist and artist who made numerous casts of ancient monuments for the museum's exhibits. He may have been the Vassalli Bey who obtained the Tuthmosis III shroud fragment from Maraini. If so, the date of his acquisition of the fragment can be narrowed down to sometime between 1885 (when Maraini contacted Erman about the fragment still in his collection) and 1887, the year of Luigi Vassalli’s death.

The manner in which Clemente Maraini first acquired the shroud fragment is, at this time, a matter of pure speculation. John Romer reports that the mummy of Tuthmosis III had been plundered by the Abd el-Rassul's family and states that its shroud and wrappings had been badly shredded in their search for treasures. Romer goes on to say that the shroud’s “torn pieces are now in several museums” (TVK, 146.) The shroud fragment at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts may have been purchased by Clemente Maraini from a dealer in Luxor or Cairo who was helping the Abd el-Rassuls to fence the antiquities they had stolen from DB320.

The MFA shroud fragment is inscribed with portions of the Book of the Dead in neatly written cursive hieroglyphs, and cartouches bearing Tuthmosis III’s throne name (Menkheperra) are clearly visible in several lines of text. The fragment is listed as “Not On View” but may be seen at the Museum of Fine Arts website here .

(Source Bibliography: CCR, 19f.; DRN,

209, 214; 92; EM, 92; EMs, 37, ill. 39; GCM, 103f.; JEA 17, 209f.; MiAE, 84,

89, 91, 116-17, 122, 128, 160, 209, 210, 226, 255, 258, 269, 315, 318,

322, 323, ills. 79, 301, 358, 359, 386, 415; MMM, 37, 57, 87,

ill. 17, 36, 174; MR, 547f., pl. 6, a; RM, 32ff.; TVK, 146; XRA,

1D5-1E2; XRP, 133, 136ff., ill. 38.)

Other Burial Data:

Original Burial: KV34

Reburials: (i) dismantled at the same

time as the tomb of Hatshepsut (KV 20) and reburied in tomb of Inhapi (WN A?) during

reign of Pinudjem I; and (ii) in DB 320 after year 11 of Shoshenq I..

(Source Bibliography: DRN, 245.)

Photo Credit: RM (Cairo, 1912,) pl.

XXVIII. Color photo of Tuthmosis III as

he appears today in the Royal Mummy Room at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo is from

Al Ahram.

For high resolution image of Tuthmosis III see

the University of Chicago's Electronic Open Stacks copy of Smith's

The Royal Mummies (Cairo, 1912) Call #: DT57.C2

vol59. plate XXVIII.

.

Source Abbreviation Key

Amenhotep II (c.

1543-1419 B.C.)

18'th Dynasty

Provenance: KV35

Discovery Date: March 9, 1898, by Victor

Loret

Current Location: National Museum of Egyptian Civilization in Fustat CG 61069

Click here for biographical data

Details: Amenhotep II is one of only two New Kingdom pharaohs to

be found (as of this time) in their own tombs in the Valley of the Kings (the other pharaoh being Tutankhamen.) His mummy sustained damage in

antiquity: the head was broken off; the front abdominal wall was

missing; the spine was broken; and the right leg and thigh were separated

from the body and from each other. Amenhotep II had been rewrapped and

given a shroud (with Linen Docket--see translation below) by the

priests in charge of restoring his tomb after it had been plundered. When Loret found the mummy, it was still covered by the shroud, which was held in place by horizontal strips of bandaging and adorned with floral garlands. (See

below for a photo of the still-enshrouded mummy.) Loret had the mummy placed in a wooden crate for shipment to Cairo, but the Egyptian government suddenly ordered him to leave Amenhotep II in the tomb. This turned out to be unwise. In 1901, modern thieves rifled the mummy while it remained in the burial chamber of KV35 and ripped the shroud and bandages off the ancient ruler in their frantic search for valuables. The photo at left shows Amenhotep II after his mummified remains had been exposed by the thieves.

The king had been tall for his times and

stood at 1.8 m (6 ft)--much taller than either his father or son. His body

is that of a robust, strongly built individual. At the time of the ruler's

death, his hair was graying and he had developed a bald spot on the back

of his head. According to G. E. Smith, the arms of Amenhotep II were

crossed with the forearms parallel and lower down than on most other

kingly mummies. Although Smith reports in 1924 (in EM,

93,) that the hands of the mummy were not tightly clenched, his

1912 account (in RM, 37,) states that the fingers of

the right hand were tightly closed, with the thumb extended. The left hand

was also closed, but Smith states that the fingers were not as tightly

clenched as those of the right hand. (The photo at left confirms Smith's 1912 report.) Unlike the mummy of his father,

Amenhotep II retained his genitals, and he had been circumcised. His teeth

were well worn but in good condition. As in the case of the mummies of

Tuthmosis II and Tuthmosis III (cf. above), the body of Amenhotep II was

also covered with raised nodules, which Smith thought could have been

caused either from a disease or by the action of the embalming materials

with the skin. (See photo below, posted by Flickr member hhrahman77which provides a color close up of the facial profile of Amenhotep II's mummy that clearly shows these nodules. The same person posted another recent photo of Amenhotep II in the Royal Mummy Room on 6/1/08.)

Amenhotep II was found in a

replacement cartonnage coffin which had been inscribed for him. This was found in a large sarcophagus in the burial

chamber of the king's tomb (see photo from BM.) According to

Loret, the floral decorations placed on the mummy's shroud consisted of a small bouquet of mimosa flowers ("...une petit bouquet de

mimosa...") and a floral crown or headpiece ("...une bouquet de fleurs et

sur les pieds une couronne de feuillage...) (quoted in DRN,

195.) Howard Carter, writing later, described the mummy as

having on his breast "a few flowers and some foliage of the olive tree."

(quoted in HCBT, 61.) Impressions of jewelry

(including that of some kind of pectoral ornament) were found in the dried

resins which had been used in the embalming process. A large bow, which

had either been broken or cut in two, was found with the

mummy.

Many objects, most of which were in a damaged

condition, were found in the tomb (see Special Exhibit: Funerary

Objects from the Tomb of Amenhotep II on navigation bar at left).

With the king, in side rooms off the burial chamber, were also found the

mummies of other New Kingdom rulers and notables (see KV 35 link

above.) (Source Bibliography: BIE, [3 ser.] 9 [1898],

108; DRN, 192-199, 210, 215, 245; EM, 92; EMs, 37,

39, 45, ill. 40; HCBT, 61; MiAE, 38, 79, 84, 96, 132, 282,

285, 315, 316, 318, 324, ills. 330, 411, 413d, 415, 425; MMM,

38, 39, 40, 84, 87, 88; RM, 36ff.; XRA, 1E3-1F1; XRP,

112, 113, 115, 116, 135, 136, 137, 138ff., 142, 157, 159, 166, ill.

39.)

Other Burial Data:

Original Burial: KV 35

(see link above.)

Inspections/Restorations: Reeves cannot

provide a very precise account of all the post-interment activity in KV 35

because the archeological evidence is difficult to interpret. He

tentatively dates one inspection/restoration of KV 35 in Year 8 of

Ramesses VI, and another in Year 13 of an unspecified king. At this time,

the cache of royal mummies was placed in room Jb (see diagram.) Next (and probably not long afterward) the

three mummies found in room Jc were placed in the tomb, all perhaps

originally in room Jd (although only the Unidentified Boy can first

be placed here with any degree of certainty, as is indicated by the

discovery of his mummified toe in this chamber. See BIE [3 ser.]

9 [1898], 106.) This was followed by a period of more illicit

pillaging, in which thieves ransacked the mummies. Finally, restorers put

the contents of the tomb back in order, and moved the three unwrapped

mummies into room Jc before sealing the tomb. (Source

Bibliography: BIE [3 ser.] 9 [1898], 106; DRN, 192-199, 210, 215, 245.)

Linen Docket: According to Loret, this simply gave the prenomen of Amenhotep II: "('Le prenom d'Amenophis II'): Akheperure." (Source Bibliography: DRN, 232.)

Photo Credit: Top photo of unwrapped mummy and coffin lid by Howard Carter, in ASAE III

(1902); color photo of mummy by Flickr member hhrahman77; bottom photo of wrapped mummy in packing crate for aborted shipment to Cairo by Howard Carter

For more on KV 35 and its discovery, see Ian Bolton's Egypt: Land of Eternity website.

Tuthmosis IV

(c. 1419-1386 B.C.)

18'th Dynasty

Provenance:

KV35

Discovery Date: March 9, 1898, by Victor

Loret

Current Location: National Museum of Egyptian Civilization in Fustat CG61073;

JE34559

Biographical data: A son of Amenhotep II, Tuthmosis IV is remembered today primarily as the royal prince who fell asleep under the Sphinx at Giza. In a dream, the Sphinx promised Tuthmosis the double crown providing that he clear away the sand which had covered most of it. Tuthmosis undertook the clearing project, and the Sphinx kept its word: Tuthmosis became Pharaoh. He commemorated this event by placing a large stela between the paws of the Sphinx which is still in place today. Zahi Hawass, on a recent television documentary, gave a more cynical interpretation to this romantic tale when he stated that Tuthmosis IV (or, more probably, the supporters of the young king) may have fabricated the whole thing to cover up the fact that he had murdered his elder brother in order to obtain the throne for himself. The scant evidence which leads some scholars to suspect foul play was the discovery at Giza of three defaced stelae inscribed for a son (or sons) of Amenhotep II. Their defacement might have been intentional; a kind of damnatio memorae intended to erase the memory of rival claimants to the throne. Additionally, as Dennis Forbes points out, why would the Sphinx promise to reward the throne to Thuthmosis IV if he were already the Crown Prince? Apparently, the kingship had been originally destined for one or more of his older brothers who never lived--for whatever reason--to inherit it.(cf. Dennis Forbes, KMT [vol. 13: 2], 45.)

Details: The mummy, which is basically intact except

for disarticulated feet, was found in room Jb of KV 35 (at position

1--see tomb diagrams) along with eight other royal mummies.

Ikram and Dodson report that the king died young, and note that the wasted

condition of his body has led to speculation that he may have suffered

from some unknown illness which eventually took his life. They also note

that both ears were pierced, and describe his fingernails as being neatly

trimmed. His arms were crossed over his chest in the now-standard royal

fashion, and his hands were clenched. A crude embalming incision was made

in the mummy, and his body cavity was filled with resin-coated linen.

Tuthmosis IV had been rewrapped in his original bandages and had been

given a new shroud with a Reeves' Type A docket on the chest area. (See

Linen Docket translation below.)

Reeves states that Tuthmosis IV was found on a white painted plank

that had been placed in his coffin. This coffin (CG61035) was a

replacement coffin covered with a layer of plaster which concealed any

original decoration (see photo of coffin from Georges Daressy's, Cercueils

des cachettes royales [Cairo, 1909.]) It had been reinscribed for

Tuthmosis IV with hieroglyphs in a column down the front. Reeves states

that this coffin was similar to the one used for Ramesses V,

and proposes that the reburial of Tuthmosis IV was perhaps undertaken at

the same time as that of Ramesses V immediately after KV 43 was abandoned.

(Source Bibliography: BIE, [3 ser.] 9 [1898], 111 [1]; CCR,

217; DRN, 211, 215; EM, 94; EMs, 39, ill. 40;

KMT [vol. 13: 2], 45; MiAE, 62, 74, 84, 96-7, 210, 258, 315,

324, ills. 69-70, 360, pl. xxxvii; MMM, 39, 76, 87, 131, ills. 28,

157; RM, 42ff.; XRA, 1F2-10; XRP, 60, 112, 136,

138, 139, 140, ill. 38.)

Other Burial Data:

Original Burial: KV 43

Restorations (whm krs): Yr

8 3 3ht 1 of Horemheb

(based on inscriptional evidence in the form of a wall docket found in KV

43 [see Wall Docket translation] indicating an

official inspection of the burial, probably occasioned by signs of illicit

activity in or near the tomb.

Reburials: In KV 35 after year 13

of Smendes. (Source Bibliography: DRN,

245.)

Linen Docket: Probably dates to the time when Tuthmosis IV was moved into KV 35 (i.e. after year 13 of Smendes.) This docket simply recorded the prenomen of Tuthmosis IV: "Menkheperure ('en grands signes hieratiques a l'encre bleu')" (Source Bibliography: ASAE 4, [1903], 110 [transcr.], 232; BIE, [3 ser.] 9 [1898], 111 [1]; DRN, 232.)

Photo Credit: All three photos: Patrick Landmann/Science Photo Library.

For high resolution images of Tuthmosis IV see the

University of Chicago's Electronic Open Stacks copy of Smith's The

Royal Mummies (Cairo, 1912) Call #: DT57.C2 vol59.

plates XXIX, XXX.