The Holy TrinityAccording to the ScripturesBy Ibrahim Aboud

The Trinity is one of the central doctrines of mainstream Christianity. Although the concept is in essence presented in the New Testament, the figures of the Trinity seem to be alluded to in many passages of the Old Testament as well. The term itself does not come to being until the end of the second century, about the same period that the New Testament canon was being formed. Early Christians knew this concept, primarily from the words of Christ and His disciples, and applied it to their reading of the Law and the Prophets; this is what was meant by the term “scriptures” in the New Testament. According to the scriptures the Church came to its understanding of the triune God and its role in the history of salvation. This reading of the Ante-Christian scriptures became the fulfillment and completion of the work of God, which was hidden from the beginning. The Trinity in the New Testament: The Father, who is the head and source, is heard rather than seen face to face in the gospels. In the baptism of Jesus, the Trinity appears: the Father in the heavens speaks, the Son on earth is initiated by John the Baptist, and the Holy Spirit as a dove bears witness to the glorious event: “And Jesus, when He was baptized, went up straightway out of the water: and, lo, the heavens were opened unto Him, and He saw the Spirit of God descending like a dove, and lighting upon Him: And lo a voice from heaven, saying, This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased” (Matt. 3:16-17). In the eyes of the Church, the physical appearance of God in the world is the Son, and all authority over creation was given to Him: “The Father loveth the Son, and hath given all things into his hand” (John 3:35). The Father, being the head of the Trinity, reserves the knowledge of and power over time, in the apocalyptic sense: “But of that day and that hour knoweth no man, no, not the angels which are in heaven, neither the Son, but the Father” (Mark 13:32). In that regard, the Father has unique and absolute knowledge of the apocalypse, which He alone possesses. However, all matters that relate to creation and the human soul in the Judgment are given to the Son, for “all things were made by Him; and without him was not any thing made that was made” (John 1:3), and “the Father judgeth no man, but hath committed all judgment unto the Son” (5:22). The Son, as the Church understood it, was born of the Father before time, since time in itself is created, and shares the Father’s titles of the Old Covenant. As God of the Old Testament was seen as “God of gods, and Lord of lords, a great God, a mighty, and a terrible, which regardeth not persons, nor taketh reward” (Duet. 10:17), likewise the Son is regarded as “the blessed and only Potentate, the King of kings, and Lord of lords” (1Tim 6:15). The incarnation of the Son in the end of times is the revelation of God’s love to humanity, as understood by the believers of the Christian faith; the Son is not only the messenger or the elected of God, but God Himself in the human flesh, the full example of the sanctified human being, the saved and resurrected Adam, and the unity of heaven and earth after the divorce caused by the fall: “For unto us a child is born, unto us a son is given: and the government shall be upon his shoulder: and his name shall be called Wonderful, Counsellor, The mighty God, The everlasting Father, The Prince of Peace” (Isa. 9:6). In the opening of the gospel of John the Theologian, the disciple uses an expression that parallels the first verse in Genesis, and applies this to the Logos: “In the beginning was the Word” (John 1:1). Christ was not seen only as a redeemer and completer of God’s work, but as the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, who comes in the flesh to save his people: “Behold, a virgin shall be with child, and shall bring forth a son, and they shall call his name Emmanuel, which being interpreted is, God with us” (Isa. 7:14, Matt. 1:23). However, the role of the Word does not start with the incarnation, but is from the beginning. Christ in the Old Testament: There was clear conviction in the early church that the incarnation of the Word and the establishment of the universal salvation in the Church through the Holy Spirit were basic signs of the Messianic age, the age in which God fulfils the promises He made to deliver mankind from the bondage of death: “Christ hath redeemed us from the curse of the law, being made a curse for us: […] That the blessing of Abraham might come on the Gentiles through Jesus Christ; that we might receive the promise of the Spirit through faith” (Gal. 3:13-14). The work of the Trinity in this sense is not limited to the Christian Covenant, but rather begins from the promises of the Old Testament and surpasses it to achieve God’s work on earth through his physical unity with man and the universal salvation by the work of His Spirit. The acceptance of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit in baptism are basic requirements to enter the Church: “Go ye therefore, and teach all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost” (Matt. 28:9). The reading of the scriptures, Torah and Prophets, in the early church was accompanied by the understanding that these books spoke of Christ (John 5:39). Paul comments on the redeeming work of Christ on earth by saying: “For I delivered unto you first of all that which I also received, how that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures; And that He was buried, and that He rose again the third day according to the Scriptures" (1 Cor. 15:3-4). In this sense, Christ says to the disciples on the road to Emmaus: “O fools, and slow of heart to believe all that the prophets have spoken: Ought not Christ to have suffered these things, and to enter into his glory?” (Luke 24:25-26). John even says in his gospel that “No man hath seen God at any time; the only begotten Son, which is in the bosom of the Father, He hath declared him” (John 1:18), and that Isaiah, who had seen Yahweh in the Holy of holies, had actually seen Christ’s Glory: “These things said Esaias when he saw His glory and spake of Him” (12:41). Every physical revelation of Yahweh in the Law and the Prophets is seen as a revelation of the Word, being the image and glory of the Father. This is emphasized in Acts and the epistles later on: Stephan tells the Jewish congregation that Christ “is He that was in the church in the wilderness with the angel which spake to him in the mount Sinai, and with our fathers: who received the holy oracles to give unto us” (Acts 7:38). In this statement, the martyr makes it apparent that the Church was in God’s design from the beginning, the fullness which was achieved through the incarnation of the Son and the delivering of the Holy Spirit (Acts 2). It was thus essential to understand the role of Christ in the promise made to Abraham, and the salvation He achieved on the cross as the fulfillment of the work He had initiated with the Israelites, and a prototype for the greater salvation of the world; in (1 Cor. 10:1-2) we read:

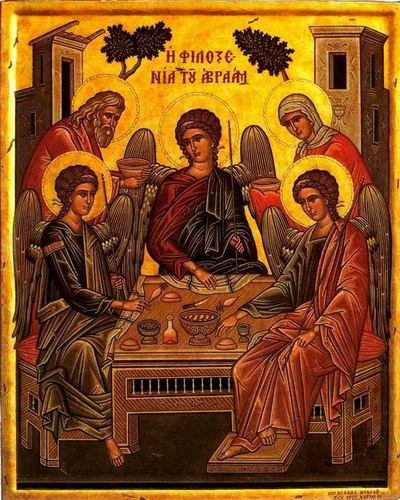

This theology is based in essence on the words of Christ Himself, who declares that He is before Abraham “Your father Abraham rejoiced to see my day: and he saw it, and was glad. […] Verily, verily, I say unto you, Before Abraham was, I am” (John 8:56,58). This verse, which suggests that Christ saw Abraham, is important because Abraham’s vision of God is a main event in the Old Testament. On hearing this proclamation the Jews hasten to stone Him because they understood that He was referring to the appearance of the Lord to Abraham. John says that the Jews sought the more to kill him, because He “said also that God was His Father, making Himself equal with God” (5:18). When Philip approached Jesus with a request to see the Father, “Jesus saith unto him: Have I been so long time with you, and yet hast thou not known me Philip? He that hath seen me hath seen the Father; and how sayest thou then, Show us the Father? Believest not thou that the Father is in me and I am in the Father” (14:9-10). The concept of Christ being “God with us” became central to understanding the Law and the Prophets to every Christian, and the basis for Christological thought for those who were called Christians from the earliest days of the Christian Church. To the apostles and early Christians of Jewish origin, the words of the prophets were fulfilled by the success of the mission of Christ, a success that had transformed the world and the lives of every nation it came into contact with. The Holy Spirit in the Old Testament: In the opening of Genesis the Spirit is the first person of the Trinity mentioned: “And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters” (Gen. 1:2). The Spirit of God is not the Father from what is suggested in many passages; for example, when the Lord speaks to Moses on the building of the tabernacle, He chooses Bezaleel the son of Uri and says of him: “And I have filled him with the Spirit of God, in wisdom, and in understanding, and in knowledge, and in all manner of workmanship” (Ex. 31:3). The Lord sends the Spirit of God to illumine those who do His work on earth; the Spirit of God is clearly not the speaker here. While the Word is the face of the Father and the representer of His presence and glory on earth, the Holy Spirit is the achiever of God’s will. He illumines and inspires the prophets; Ezekiel says: “And the Spirit entered into me when He spoke unto me. And set me upon my feet, that I heard Him that spake unto me. And He said unto me, son of man, I send thee to the children of Israel, to a rebellious nation that has rebelled against me” (Ezek. 2:2-3), and in 1 Samuel we read: “And when they came thither to the hill, behold, a company of prophets met [Samuel]; and the Spirit of God came upon him, and he prophesied among them” (1Sam. 10:10). In that sense did the apostles understand the role of the Spirit and concluded that “the prophecy came not in old time by the will of man: but holy men of God spake as they were moved by the Holy Ghost” (2 Pet. 1:21). In Acts, Paul confirms this belief by saying “Well spake the Holy Ghost by Esaias the prophet unto our fathers, Saying, Go unto this people, and say, Hearing ye shall hear, and shall not understand; and seeing ye shall see, and not perceive” (Acts 28:25-26). Through the Holy Spirit the incarnation of the Word is achieved; in the angel’s address to Joseph we hear: “fear not to take unto thee Mary thy wife: for that which is conceived in her is of the Holy Ghost” (Matt. 1:20), and to Mary the angel Gabriel declares the trinitarian roles in the incarnation of the Word by saying to her: “The Holy Ghost shall come upon thee, and the power of the Highest shall overshadow thee: therefore also that holy thing which shall be born of thee shall be called the Son of God” (Luke 1:35). Through this prophetic Spirit the mother of John the Baptist praises the conception of Jesus by blessing His mother: “Elisabeth was filled with the Holy Ghost: And she spake out with a loud voice, and said, Blessed art thou among women, and blessed is the fruit of thy womb” (Luke 1:42). The Holy Spirit’s role is thus central to the salvation of mankind, even before the resurrection of Christ and the formation of the New Testament church. The Holy Spirit is essential to understanding the Christian God, and His relationship to human salvation. He is God in the full sense, and any worship and reverence that is fit for the Creator applies to Him. The rejection or denial of the Holy Spirit is seen in the gospels as a catastrophic blow to salvation: “Wherefore I say unto you, All manner of sin and blasphemy shall be forgiven unto men: but the blasphemy against the Holy Ghost shall not be forgiven unto men. And whosoever speaketh a word against the Son of man, it shall be forgiven him: but whosoever speaketh against the Holy Ghost, it shall not be forgiven him, neither in this world, neither in the world to come” (Matt. 12:31-32). The importance of the Holy Spirit is that of great consequence, and denial of His presence and role does not produce error alone, but irreparable damnation. The Holy Spirit, as defined by Jesus in chapters 14, 15, and 16 of the Gospel of Saint John, resumes His work in the Church after the ascension of Christ. The source of the unseen Spirit is the Father, and His role is complementary to that of the Son: And I will pray the Father, and He shall give you another Comforter, that He may abide with you for ever; Even the Spirit of truth; whom the world cannot receive, because it seeth Him not, neither knoweth Him: but ye know Him; for He dwelleth with you, and shall be in you. […] But the Comforter, which is the Holy Ghost, whom the Father will send in my name, He shall teach you all things, and bring all things to your remembrance, […] But when the Comforter is come, whom I will send unto you from the Father, even the Spirit of truth, which proceedeth from the Father, He shall testify of me: And ye also shall bear witness. The procession of the Holy Spirit from the Father became a major issue between the churches of the East and the Church of Rome in the eleventh century, in what is known as the Filioque (and the Son) controversy. Eastern churches insisted on the definition given by John, while Rome found it necessary to insert “and the Son” into the creed. The statement: "and in the Holy Spirit, the Lord and Giver of Life, Who proceeds from the Father and the Son" became the direct cause for the schism (Popof 95-118). The basic understanding of the trinitarian relationship was that the Son is born from the Father, while the Holy Spirit proceeds from Him. The difference between the two acts, according to the fathers, remains unknown to us, and our understanding of this matter is limited to the clues we find in Christ’s promise (Damascus 142-143, bk. VIII). The apostles in the Church are the messengers of the New Covenant; they speak the words of the Father through the wisdom of the Holy Spirit: “But when they shall lead you, and deliver you up, take no thought beforehand what ye shall speak, neither do ye premeditate: but whatsoever shall be given you in that hour, that speak ye: for it is not ye that speak, but the Holy Ghost” (Mk 13:11). The Holy Spirit is not merely the action of God, but is rather a divine person that has a role and mission which completes the roles of the Father and the Son in the Church: “Now we have received, not the spirit of the world, but the spirit which is of God; that we might know the things that are freely given to us of God. Which things also we speak, not in the words which man's wisdom teacheth, but which the Holy Ghost teacheth; comparing spiritual things with spiritual” (1 Cor 2:12-13). The Holy Trinity in the Old Testament: In many areas of the Old Testament one can see trinitarian symbols and metaphors. The hailing of the Lord in Isaiah’s vision in the temple’s holy of holies is one important incident that reflects such an assumption: “And one [seraphim] cried unto another, and said, Holy, holy, holy, is the Lord of hosts: the whole earth is full of His glory” (Isa. 6:3). But the focus of this paper will be on one story in Genesis in which God appears in the body to Abraham, the father of the faith, to make him His great promise and cast judgment on the sins of Sodom and Gomorra. The most important reference to the Trinity in the Old Testament is when Abraham is visited by the three angels in the plains of Mamre. The manner in which Abraham receives and addresses the men is essential. The text remains closer to the original in the King James Version, which does not tamper with its irregularity when it comes to numbers. The story opens with “And the Lord appeared unto him in the plains of Mamre” (Gen. 18:1), and follows this by saying that Abraham “lift up his eyes and looked, and, lo, three men stood by him: and when he saw them, he ran to meet them from the tent door, and bowed himself toward the ground” (18:2), which is only fit for God, for it is sinful by the Law to revere men or angels in such a manner. The text does not refer to any of them as having a special divine nature; we are merely told that they are all men, but Abraham obviously understands who the visitor is. Abraham then calls the three as one saying: “Let a little water, I pray you, be fetched, and wash your feet, and rest yourselves under the tree, and I will fetch a morsel of bread, and comfort ye your hearts; after that ye shall pass on: for therefore are ye come to your servant. And they said, So do, as thou hast said” (18:5). It is common to address a singular in the plural to project reverence, but here the opposite occurs: the plural is addressed as singular. After preparing a tender and good calf, suitable for a divine sacrifice, Abraham gives the men the food “and they did eat” (18:8). This act reminds one of the incidents in which Christ ate with his disciples after his resurrection (John 21:9-13) and (Luke 24: 30-31), even though His body was able to enter while “the doors were shut” (John 20:19). Paul comments on this body by saying: “It is sown a natural body; it is raised a spiritual body” (1 Cor. 15:44). It is safe to assume that the angels/men/Lord did dine at Abraham’s in like manner. The men begin to speak to Abraham after the meal; at first they all speak at once: “And they said unto him, Where is Sarah thy wife? And he said, Behold, in the tent”(Gen. 18:9), then only one speaks to him: “And he said, I will certainly return unto thee according to the time of life; and, lo, Sarah thy wife shall have a son. And Sarah heard it in the tent door, which was behind him. (18:10). When Sarah laughs within herself at this proclamation, this speaker, who is then identified as the Lord, knows of this and answers: “And the Lord said unto Abraham, Wherefore did Sarah laugh, saying, Shall I of a surety bear a child, which am old? Is any thing too hard for the Lord? At the time appointed I will return unto thee, according to the time of life, and Sarah shall have a son. Then Sarah denied, saying, I laughed not; for she was afraid. And he said, Nay; but thou didst laugh.” (18:15). Now “the men rose up from thence, and looked toward Sodom: and Abraham went with them to bring them on the way” (18:16). In an aside the Lord says: “Shall I hide from Abraham that thing which I do; Seeing that Abraham shall surely become a great and mighty nation, and all the nations of the earth shall be blessed in him? For I know him, that he will command his children and his household after him, and they shall keep the way of the Lord, to do justice and judgment; that the Lord may bring upon Abraham that which he hath spoken of him” (18:19). The Lord then turns to the issue of Sodom and Gomorrah: “And the Lord said, Because the cry of Sodom and Gomorrah is great, and because their sin is very grievous; I will go down now, and see whether they have done altogether according to the cry of it, which is come unto me; and if not, I will know” (18:20-21). It is suggested then that it is the Lord that goes down to the city to judge its sins. The “men,” now only two of them, leave to the city without waiting to find out the result of the Lord’s conversation with Abraham, in which he haggles with the Lord so that He would have mercy on the city: “And the men turned their faces from thence, and went toward Sodom: but Abraham stood yet before the Lord. And Abraham drew near, and said, Wilt thou also destroy the righteous with the wicked?” (18 22-23). Abraham begins negotiating with the Lord over how many righteous inhabitants would suffice to save the city, and they went thus from fifty to ten persons. Then “the Lord went his way, as soon as he had left communing with Abraham: and Abraham returned unto his place” (18:33). In chapter 19, the two men, or angels as referred to at times, whom we had left earlier, arrive in Sodom: “And there came two angels to Sodom at even; and Lot sat in the gate of Sodom, and Lot seeing them rose up to meet them; and he bowed himself with his face toward the ground” (19:1). As in the incident with Abraham, if Lot were worshipping two men or angels, he would be in direct violation of the Law; the text does not suggest any such objection to his behavior. Lot then addresses them in the plural saying: “Behold now, my lords, turn in, I pray you, into your servant's house, and tarry all night, and wash your feet, and ye shall rise up early, and go on your ways. And they said, Nay; but we will abide in the street all night” (19:2). Lot then urges them to stay, “and they turned in unto him, and entered into his house; and he made them a feast, and did bake unleavened bread, and they did eat” (19:3). Here is an interesting reference to unleavened bread, which appears formally in the exodus from Egypt to symbolize the quick salvation from captivity: “Thou shalt eat no leavened bread with it; seven days shalt thou eat unleavened bread therewith, even the bread of affliction; for thou camest forth out of the land of Egypt in haste” (Duet. 16:3). The bread symbolizes the hasty exodus of Lot and his family from the city to escape death. Moreover, it is not only given to Lot and his family, but is shared by the two men. This partaking of the physical bread with a divine being does not occur again in the Bible until the coming of the Messiah. Knowing of the presence of the men in Lot’s house, the men of Sodom gathered to rape the visitors, while Lot argued with them, offering even his daughters to them instead. As they eventually turned against Lot himself, “the men put forth their hand, and pulled Lot into the house to them, and shut the door. And they smote the men that were at the door of the house with blindness, both small and great” (Gen. 19:10-11). The “men” then ask Lot to warn his relatives: “for we will destroy this place, because the cry of them is waxen great before the face of the Lord; and the Lord hath sent us to destroy it” (19:13). Lot fails to convince anyone of the judgment that is to come, “And when the morning arose, then the angels hastened Lot, saying, Arise, take thy wife, and thy two daughters, which are here; lest thou be consumed in the iniquity of the city. And while he lingered, the men laid hold upon his hand, and upon the hand of his wife, and upon the hand of his two daughters; the Lord being merciful unto him: and they brought him forth, and set him without the city” (19:16). Lot then addresses both as a single being: “And Lot said unto them, Oh, not so, my Lord. Behold now, thy servant hath found grace in thy sight, and thou hast magnified thy mercy” (19:18). There is a sudden shift to the singular after this conversation, and the text reads: “And he said unto him, See, I have accepted thee concerning this thing also, that I will not overthrow this city, for the which thou hast spoken. Haste thee, escape thither; for I cannot do anything till thou be come thither” (19:22). The interchangeable roles of the angels are fascinating in this passage; the Lord is present both with Abraham and with Lot through the angels. There is no clear identification of which is the Lord, although one may assume that the Lord was only the one Abraham bargained with earlier. However Lot addresses the men as Lord, and the text refers to the two angels as “He” and “Lord” in the same style of the previous chapter. We are left with no clear knowledge of the nature of these beings; are they men or angels? Are they one or three? Or are they Yahweh? The text also includes foreshadowing of the promise, the judgment, and salvation from death, which are roles of the triune God in the Christian Covenant. The Trinity in the Early Church: We have established so far that the concept of the Trinity is biblical, revealed in the beginning to Abraham and clarified by Christ. Abraham’s story is significant because of the deliberate confusion it casts on the nature of these beings (mortal or angelic?), and the fact that they are the Lord Himself in the flesh at the same time, even when they are physically in different locations. This concept is central to understanding God and the meaning of the scriptures, which are “a shadow of good things to come” (Heb. 10:1). Nevertheless, the term Trinity is not mentioned in the Bible itself. The use of this term appears for the first time in the writings of Theophilus of Antioch (170 AD), who writes: “In like manner also the three days which were before the luminaries, are types of the Trinity [Τριάδος], of God, and His Word, and His wisdom. And the fourth is the type of man, who needs light, that so there may be God, the Word, wisdom, man” (Theophilus 101, bk. II). Although the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are used in earlier writings and liturgies, the shorthand term Trinity is coined from Greek to describe the triune God at a later time. It is significant to point out here that the use of this term is contemporary to the establishment of the first list of canonical books, and the assembly of many local councils in Rome, Syria, and Asia Minor to combat the multitude of heresies. Due to the great number of these movements, I will resort to mentioning only a few that endangered the trinitarian belief. Marcion (144 AD), from Pontus, believed that the cruel god of the Old Testament is not the loving one of the New Testament, and is therefore unrelated to Christ or the Church. He thus objected to the use of passages from the Old Testament in the gospels, and refused to recognize the apostolic tradition or epistles that disagreed with his views. The Church quickly condemned the spreading of this ideology, and sought to collect the writings of the apostles and authorize a list of books that represented its apostolic faith. Sabellius (215 AD), who came from Northern Africa to Rome, believed in three faces of the same God, not three persons of one essence. He thus taught that God was of one indivisible substance, with three different functions in time. He was excommunicated by Pope Calixtus I in 220 AD (رستم 63-6). Another major heresy was Montanism, which started in Phrygia, in the second half of the second century. Montanus, who was a priest of the ecstatic cult of Cybele before converting to Christianity, began prophesizing in the year 172 AD. He taught his followers that second marriages were acts of adultery, enforced strict fasts, taught of non-forgiveness to those who fell in great sins, and despised arts and science. His movement continued spreading until it reached Leon in the time of Elvuthreius, Bishop of Rome (174 – 189 AD). Before 190 AD the heresy had already reached Antioch, forcing its bishop Serapion (190 – 211 AD) to send a letter to the hierarchs Kryxus and Pontius containing signatures of various bishops in the Church excommunicating it (Eusebius 229-237, bk. V). The heresy reached Rome before the year 200 AD, and many discussions were held with its followers. The Canon of Muratori (170 – 180 AD) mentions Montanism (the Cataphrygians) among heresies and rejects its teachings and writings (Muratorian). Tertulian, who adopted the fundamentalist and ecstatic Pentecostal teachings of Montanus, believed that salvation had three stages, of which the Holy Spirit initiated the third, the stage where the Church must reach the peak of its organization. He believed that bishops had no power over binding and loosening church affairs. In his opinion, the Church has abandoned the prophetic inspiration, not knowing that his search for that "inspiration" led him directly outside the Church (Tertulian 99). In the third century Arius taught that the Son was created, that His divinity was not before time, and that He was not of one essence with the Father. In 315 AD, now a legal institution in the Roman Empire, the Church was able to have a large council in Nicea, and the Arian case was discussed and condemned as heresy. The council then issued a creed that defined the relationship of the Father to the Son (رستم 192-205). Macedonius, who rose a few decades later, taught that the Holy Spirit was not a person of the Trinity, but rather the “energy” or “action” of God. He was condemned in the Second Ecumenical Council in Constantinople (385 AD), and the second portion of the creed, concerning the Holy Spirit, was expanded to define His role (246, 255). The Nicea-Constantinople creed is not the first creed or formula of faith made in the history of the Church. This is however the first time such a creed was “internationalized” to cover the entire Roman Empire. Churches outside the borders of this empire, Armenians and Assyrians for example, had already known and believed what was in this creed. The Nicean portion of the creed is in reality a modified confession of belief that was already established in older local councils. The creed affirms the universal ecclesiastical confession of the faith: the belief in one God, the Father Almighty, and in one Lord Jesus Christ, and in the Holy Spirit. It is vital for a Christian to believe in the triune God, the Trinity of one essence, without division or confusion. The Son and the Spirit are not additions to the monotheistic faith of Abraham and the prophets, but are rather revelations of the hidden truths of the Old Testament, according to the followers of Christ. With that in mind, the Church confesses the Trinity's role from the beginning, continuing its mission in the world by the resurrected Son and through the interceding and guiding Holy Spirit, who make known to us the love of the Father. Works Cited Eusebius. “The Church History.” The Early Church Fathers. Alexander Roberts, et al, eds. Vol 24. Peabody: Hendrickson. 1994. 38 vols. 211-246. Holy Bible: King James Authorized Version. Michigan: The Zonderva Corporation. 1994. John of Damascus. “On the Trinity.” The Early Church Fathers. Alexander Roberts, et al, eds. Vol 32. Peabody: Hendrickson. 1994. 38 vols. 135-154. Ostroumoff, Ivan. The History of the Council of Florence. Trans. Popoff, Basil. Boston: Holy Transfiguration Monastery. 1971. Tertulian. “On Modesty.” The Early Church Fathers. Alexander Roberts, et al, eds. Vol 4. Peabody: Hendrickson. 1994. 38 vols. 74-101. Theophilos of Antioch. “Theophilos To Autolycus.” The Early Church Fathers. Alexander Roberts, et al, eds. Vol 2. Peabody: Hendrickson. 1994. 38 vols. 94-110. "The Muratorian Canon." Early Christian Writings. Ed. Peter Kirby. June 5, 2005. <http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/muratorian.html>. رستم، أسد. كنيسة مدينة الله انطاكية العظمى. الجزء 1. بيروت: منشورات النور. 1960. [Rustum, Assad. The History of the Church of the City of God Antioch the Great. Vol 1. Beirut: Al-Noor Publications, c. 1960. 3 vols.] * This article was published in the Fall

2005 issue of Theandros: an online Journal of Orthodox Christian Theology

and Philosophy. Vol. 3. number 1.

|