Now Playing: High All The Time vol 1

Everyone loves THREE DAYS OF THE CONDOR (1975). It's the kind of movie you could recommend to a co-worker who wants something un-seen that doesn't offend her. With 100% certainty she'll report back that it was 'really good' with a tone of slight surprise in her voice. And she'll be right.

Or will she? I loaded up the DVD last night for what I think is my fourth viewing of the 'Condor'. The storyline, which may have the viewer almost as puzzled as Robert Redford's protagonist on the first round, is completely familiar to me, as are a number of crucial scenes. What is not retained in my skull is the special mood of this movie, something we unfortunately can't retain in our cortical memory banks, but need to experience directly for full appreciation, much like the flavor of a favorite ice cream. I remember distinctly that the Condor hit a special mood which I suspect is the reason people like it, but since I cannot summon its presence at will, it is with a certain expectation that I press <Play> and lean back in the chair, lights dimmed and speakers hooked up.

The exposition deals with a rather substantial problem, which is to introduce us to a work-place and its employees in a way that makes the viewer respond properly to the shocking mass murder that occurs just a few minutes into the film. We know from the very start that something is going to happen due to classic thriller signals of people secretly staking out the building. Sydney Pollack uses Robert Redford's arrival to introduce us to all, literally, people who are soon to be hit by the murder squad. The mood inside is a pleasant mix of intellectual conservatism and high tech, into which 'Turner' (Redford) injects some friendly, ironic banter.

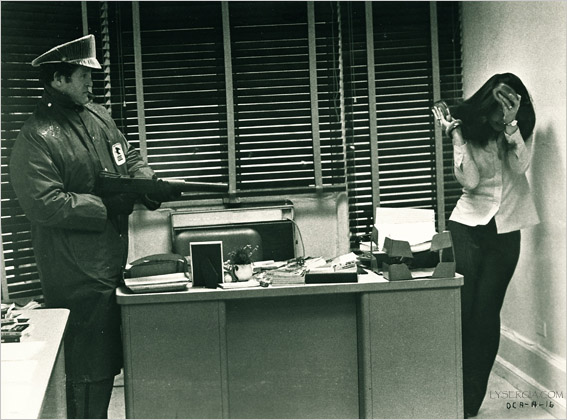

As glimpses are offered of their activities, the mystery of what work actually goes on in this office demands attention. Is it some kind of upscale book store? The faculty building for a nearby private college? Nothing seems quite to fit. This subtly but shrewdly presented riddle requires the viewer to activate yet another brain circuit, in addition to registering the threat from the outside and enjoying the relaxed, bookish atmosphere inside. Rather than giving away the answer, Pollack turns on the ignition of his thriller engine and sets its big wheels in motion by having 'Turner' leave the office to pick up lunch. The half-dozen murders that follow have an appropriately shocking effect in the realm of the peaceful office and likable staff, and Pollack rightly stages the sequence in much the same way as we see Hollywood killings today: striving for realism*, neither excessive nor polite.

The spectacular mass murder is also surprisingly void of information for either the victims or the viewer--no demands or requests are made, nothing is asked for, and the killers do not communicate anything except operational dialogue. We do catch a personal glimpse of their leader, whose almost considerate behavior towards one victim plants another enigma for the viewer. As 'Turner' returns to find his colleagues massacred, Redford and Pollack face another artistic challenge, as common sense dictates that Turner should search the entire 2-story office to look for survivors or even perpetrators, finding instead murdered friends over and over, with little variation. Pollack chose to shoot this 'verbatim', turning it into an acting challenge rather than an editing challenge, and while Redford begins the sequence well, he handles the rest mainly by underplaying it, which was probably the wisest move. I'm not sure even a 1970s model Robert De Niro could have pulled those scenes of repetetive horror off in a convincing manner.

Unfortunately, Redford does not offer the proper horrified reaction when finding his girlfriend killed, instead treating it with much the same detached disbelief as with his colleagues. If she really was his girlfriend, and it certainly seems that way, why doesn't the main character react more strongly to her death? The issue lingers during the movie as a question-mark, which is not straightened out when Redford later refers to her as a 'friend' with a sad voice. The murdered girlfriend (or not) may be a remnant from the novel the script is based on, and the main character's questionable response to this personal tragedy may not have appeared as a problem until after the editing. Rather than removing her completely (by making her simply another co-worker of Turner), or allowing Redford a scene or two of grief to properly balance the emotional see-saw, Pollack ends up in a problematic space in-between. It's not a major glitch, and Redford's convincing display of terrified confusion following the murders, along with the rich array of questions and the rapid tempo, help take the viewer's mind off it. But at the fourth screening it still bothers me.

Oddly, I found the rapidly blossoming love affair with Faye Dunaway's 'Katherine' fairly convincing. As you remember from Out Of Sight, Jennifer Lopez complains that the 'Condor' couple fall in love too fast, but I don't see it that way. A certain amount of time passes, and it is also clear from the beginning that 'Katherine' is not just an ordinary female kidnapping victim, but an unusual woman with something of a hidden darkness about her. As a role she reminds me a bit of Cybill Sheperd's 'Betsy' in Taxi Driver; another interesting female character who quickly emerges as more than just what the protagonist sees. There is also a 'Stockholm Syndrome' aspect to consider. Pollack does not offer any strong pointers towards this phenomena, which became famous shortly before the movie was made, but the interpretation could be made. In short, I do not agree with JLo, although I may object to the realism of some of 'Katherine's' spy games later in the movie.

Three Days Of The Condor is almost certainly the coziest mass-murder movie ever made. Its lingering mood is not one of paranoia, but almost the opposite. We see the killings, Hank Garrett's frightening henchman, Max von Sydow's calculating assassin, the power of the corrupt CIA, and so forth, but it does not register enough to upset the atmosphere that was instilled in the opening scenes. This is a curious, uncommon effect, and almost certainly the reason why so many people like it. The scenes with Redford and Dunaway in 'Katherine's' home are clearly vital to maintain the feeling of warmth and safety: not just for the fleeing 'Turner' but also for the introvert 'Katherine' who, one feels, has never met a man who understands her. She comes into their strange relationship with a different kind of baggage than Turner, yet both of them are looking for the same thing; his quest is of the moment and open to see, her quest is long-term and more abstract, but ultimately it turns out to be the same thing from different perspectives; safety, trust, warmth. The latter aspect is cleverly enforced by the script, which puts the couple wrapped tight in bed after they just met, as Turner needs to sleep and must keep her from calling the police. After some turns of the storyline they end up in bed a second time, now with the more familiar motivation. In another, very well-written scene, Turner describes Katherine's photos of November imagery in what sounds like negative terms, then ends his critique by stating simply that he 'likes them'. Katherine for her part describes how she sometimes takes accidental pictures that does not look like what she intended at all, and those are the ones she likes the most. These exchanges, which are reminiscent of some of Woody Allen's better moments, provide solid nutrition for the idea of their rapidly emerging relationship; it happens through strange circumstances and all via chance, but so do any number of successful real-life affairs.

The cozy feeling, the 'November mood' if you will, is carefully nurtured by Pollack throughout. Von Sydow's assassin is charming, polite, helpful, and just. The CIA director, played with marvellous authority by John Houseman, is educated, wise and thoughtful, while his underling (Cliff Robertson) is charming, straight-forward, concerned. In other words, three classic bad guy archetypes are loaded with positive attributes, and portrayed by actors whose simple presence will lend weight to these assets. The rogue CIA agents that emerge as the real bad guys are not given much in terms of personality at all, and they are cast using fairly unknown actors whose outward appearance confirm the idea of a corrupt government agent.

The cozy feeling, the 'November mood' if you will, is carefully nurtured by Pollack throughout. Von Sydow's assassin is charming, polite, helpful, and just. The CIA director, played with marvellous authority by John Houseman, is educated, wise and thoughtful, while his underling (Cliff Robertson) is charming, straight-forward, concerned. In other words, three classic bad guy archetypes are loaded with positive attributes, and portrayed by actors whose simple presence will lend weight to these assets. The rogue CIA agents that emerge as the real bad guys are not given much in terms of personality at all, and they are cast using fairly unknown actors whose outward appearance confirm the idea of a corrupt government agent.

Pollack obviously wanted to create a realistic spy movie in which the natural paranoia was to be resolved and give way towards feelings of trust and safety, rather than the nihilism that we take almost for granted in political thrillers. It would seem a difficult task to turn the table on a genre which very essence is paranoia and cynicism, but Pollack demonstrates how it can be done with familiar, effective tools. The scenography (Turner's office, Katherine's apartment) and weather (rain showers recur and are discussed) and even the wardrobe are geared towards the cozy and familiar, as seen in John Houseman's gentlemanly bow tie and dinner jacket, or the extravagant furlined coat worn by Robertson in one scene. In addition, the fundamental raison d'etre for the whole plot, Turner's frightening theory of a CIA inside the CIA, is given so little attention that it becomes almost a McGuffin, and once this theory is accepted by Houseman's CIA director, the rogue group is effectively terminated.

The political message of Three Days Of The Condor is that the CIA is run by decent people who can basically be trusted to do the right thing, and will strike down on corruption or anti-democratic activity. This is not precisely the view we are used to see of the Agency (or NSA), whether in 2013 or 1975, and the benign nature of this message corresponds with the benign, cozy atmosphere of the entire movie. In fact, this encouraging picture of a government agency may have been an impetus for the idea of making a spy thriller where the lasting moods are safety and trust instead paranoia and nihilism, even when several innocent people are killed during the first few minutes. Pollack may also have sensed a need for positive vibes in the wake of Watergate. Either way, some minor quibbles** aside, he pulled it off. 8/10

*by realism I mean what a movie audience has come to consider a 'realistic' gunshot murder scene, not how it actually looks in the real world, which few people thankfully have seen

**one might feel that Redford's protagonist is awfully adept at close-range fighting for a book-worm, as seen in the long and well-directed rumble with the 'Mailman'. However, to Pollack's credit, 'Turner' does lose the fight and is only saved at the last second by 'Katherine'.