What's New!

Detailed Sitemap

All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it. Text edited by Rosamie Moore.

|

Garibaldi's Defence of the Roman Republic

Garibaldi's Defence of the Roman Republic

Excerpts from George Macaulay Trevelyan's 1910 Book

Longmans, Green, & CO.

London, New York, Bombay and Calcutta

Foreword

This page is dedicated to the Italians who support Mr. Silvio

Berlusconi and his associates: they may not fully realize that in so doing they are putting at risk

the unity of Italy for which their fathers so bravely fought.

Short Biography of George Macaulay Trevelyan

(from The Columbia Encyclopedia)

1876-1962, English historian; son of Sir George Otto Trevelyan. Educated at Cambridge, he became professor of modern

history there in 1927 and was master of Trinity College from 1940 to 1951. He was a master of the so-called literary

school of historical writing, and his reaction against 'scientific' history has had tremendous influence. He did not,

however, ignore the scientific aspects of historical scholarship; rather he asserted that the historian must elucidate his

subject through imaginative speculation, based on all possible evidence, and present it by means of highly developed

literary craftsmanship. His most ambitious works are an extended study of Garibaldi (3 vol. *, 1907-11) and a history of England under Queen Anne (3 vol., 1930-34). He is perhaps better known for

his one-volume History of England (1926), his British History in the Nineteenth Century (1922), and England under the Stuarts (1907). Other works include biographies of John Bright (1913), Lord Charles Grey (1920), his father, Sir George Otto Trevelyan (1932), and Lord Grey of Fallodon (1937); The English Revolution, 1688-1689 (1938); English Social History (1942; pub. in an illustrated version in 4 vol., 1949-52); and An Autobiography and Other Essays (1949).

(*) Garibaldi and the Defence of the Roman Republic; Garibaldi and the Thousand; Garibaldi and the Making of Italy.

Methodological Note

The excerpts were chiefly taken from the central chapters of the book:

Chapter VI: The Republic, Mazzini, and the Powers - Oudinot advances on Rome

Chapter VII: The Thirtieth of April

Chapter VIII: Garibaldi in the Neapolitan Campaign - Palestrina and Velletri, May 1849

Chapter IX: The Third of June - Villa Corsini

Chapter X: The Siege of Rome, June 4-29

Chapter XI: The Last Assault, June 30 - Fall of Rome - Departure of Garibaldi

The third part of this chapter as well as:

Chapter XII: The Retreat I - Rome to Arezzo - Escape from the French, Spaniards and Neapolitans

Chapter XIII: The Retreat II - From Tuscany to the borders of San Marino - through the Austrian Armies

Chapter XIV: San Marino and Cesenatico

Chapter XV: The Death of Anita

Chapter XVI: The Escape of Garibaldi

Chapter XVII: The Embarkation (for Elba and Piedmont)

were entirely omitted.

Occasionally the original text was slightly amended to take care of the missing paragraphs.

The following pages contain the most important links included in the text:

Villa Pamfili/Arch of Acqua Paola (Deep Lane)

Villa Corsini/Il Vascello/San Pancrazio

Porta San Pancrazio/Janiculum/Villa Spada

Porta Portese/The Walls of Pope Urban VIII

Villa Savorelli (Casino del Giardino Farnese)

San Pietro in Montorio

|

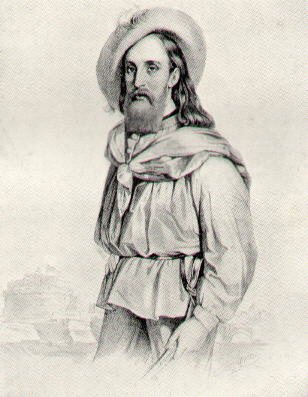

Giuseppe Garibaldi in 1849

(from a contemporary print)

Giuseppe Garibaldi - first years

Giuseppe Garibaldi was born at Nice, in a house by the sea shore, on July 4, 1807, as a subject

of the great Emperor. On Napoleon's fall he became a subject of the restored royal house of Piedmont.

The inhabitants of Nice were in part French and in part Italian. Garibaldi's family was Italian

having come from Chiavari, beyond Genoa, about thirty years before he was born.

From the age of fifteen to the age of twenty-five he worked his way up from cabin-boy to captain in the

merchant craft of Nice. So the sea became the real school of Garibaldi; he sailed in the Levant

during the Greek War of Independence among old historic tyrannies cruel as fate, and new-born hopes

of liberty fresh and dear as the morning; among the sunburnt isles and promontories that roused

Byron's jaded passions to splendour: in those waters Garibaldi caught the belief that it is better to

die for freedom than to live a slave.

It was in his voyages in the Levant that he first came across men with the passion for liberty,

and it was beyond the sea that he first met Italian patriots, exiles who instructed him that he had a country

and that she bled. He, too, like these Greeks, had a country for which to fight.

In 1832 Garibaldi joined "Young Italy" the association founded in the previous year by Giuseppe Mazzini

and calling for Italian unity. In 1834 Garibaldi had a role in a failed attempt to raise a rebellion against the autocratic government of King

Charles Albert of Piedmont (official title: King of Sardinia). He escaped to Marseilles where he learnt that the Piedmontese

Government had condemned him to death.

In South America

Having made the ports of Europe too hot to hold him, Garibaldi disappeared from the Old World

for twelve years (1836-48) to reappear famous when next his country had need of him.

In South

America Garibaldi acquired fame in the defence of Montevideo, the capital of Uruguay attacked by overwhelming

Argentinian forces. There he founded an Italian Legion and it was with a few members of this small army that

in April 1848 he set sail for Italy, where in March the population of Milan had risen and driven

the Austrians out of the city.

Back in Italy

Driven out of Milan, the Austrians had fallen back into four great fortresses, Verona, Mantua, Legnago

and Peschiera, which guarded the mouth of the Brenner Pass which ensured communication between Italy and Austria.

On July 3, Garibaldi offered his sword to King Charles Albert but his services were refused. On July 25

the royal forces were defeated by the Austrians, who in a matter of days occupied again Milan and forced the king

to ask for an armistice. The Austrians had recovered all their Lombard and Alpine territories with the exception

of Venice where Daniele Manin had proclaimed the resurrection of the Venetian Republic.

Events in Rome

Garibaldi and his followers after a failed attempt to raise the population of the Alpine valleys

in November 1848 reached Bologna where they received a warm welcome; the Papal government led by

Pellegrino Rossi let them in as they wanted to reach Venice, besieged by the Austrians. But on November 15 Rossi

was murdered in Rome, the Pope felt threatened and escaped along the Appian Way to Gaeta in Neapolitan territory.

A Provisional Government led on February 8, 1849 to the proclamation of the Roman Republic. Garibaldi formed a

legion with many recruits coming from Piedmont, Austrian Lombardy and Venetia.

King Charles Albert's defeat

On March 14, 1849 King Charles Albert of Piedmont denounced the armistice and gathered his forces

for a last rush on Milan, but his opponent, General Radetzky, was better prepared than he. Crossing

into Piedmontese territory, the Austrians won the decisive victory of Novara where

brave fighting and bad generalship distinguished the Italian army.

Charles Albert had vainly sought death in the battle. To obtain better terms for his country

he abdicated the throne. Before that summer was ended, he had died in a Portuguese cloister,

his heart broken for Italy. His son, young Victor Emmanuel, saved Piedmont

from conquest, partly through the assistance of very serious threats made

by France against Austria, partly by consenting to abandon for the time the Democratic parties in the rest of Italy.

Austria insisted that he should leave Venice to its fate by the withdrawal of his fleet

from the Adriatic, but there was one thing which he would not surrender, and that was the

Constitution granted by his father to Piedmont.

Impact on Rome

The news that Piedmont was once more laid low reached Rome at the end of March. The first result was

that the Roman Assembly proclaimed a dictatorship of Mazzini, Saffi and Armellini, under the title

of "Triumvirs", with full executive power. Mazzini, however, directed the policy of his two colleagues

as absolutely as the First Consul Bonaparte had directed the policy of Siéyès and Ducos.

From the end of January to the middle of April the Garibaldians were stationed at the border town of Rieti,

in face of the Neapolitan enemy. It was here that the Legion rose in numbers from 500 to about 1,000 men and at

length obtained discipline, organisation and equipment.

It was clear that the military defenders of the new State would have no sinecure. Spain, Austria, and

France were competing with Naples for the honour and advantage of restoring the Pope, although the Republic, whose destruction

was regarded as the moral duty of the first Catholic power that could send enough troops to Rome,

not only gave no diplomatic justification for interference, but set up within its own borders a standard of freedom

and toleration entirely new in the history of Governments beset with foreign and domestic danger.

Regardless of the truth, the Clerical party proclaimed to Europe that their enemies were communists

and socialists - names then as odious to the propertied classes as the name Jacobin had been fifty years before.

On the whole, the Republic grew more popular with the various classes of the community as its

intentions and character became more clear. The Trasteverines and other inhabitants of Rome were growing

every day more strongly opposed to the restoration of the clerical rule.

While the Republic was daily strengthening its authority and improving its moral position, the armies of

Austria, Naples, Spain and France were hastening by sea and land to its overthrow. The Austrians began slowly to occupy

the Romagna. But the French were in a position to strike a blow at the heart.

French intervention

On April 25, some eight to ten thousand French troops landed at Civitavecchia, forty miles north-west of Rome.

The orders given to Oudinot by his Government spoke of the Roman Republic as un unpopular usurpation,

which would soon be removed. He was to effect the occupation of the capital as a friend, although if the

inhabitants were so absurd as to object to the entrance of a foreign army within their walls, he must employ

the necessary amount of force.

The executive of the French Republic was more responsible than the legislature for this novel development of

the nation's foreign policy - from friendship with the Liberal cause to alliance with its worst enemies. The new

President, Louis Napoleon, heir to the traditions of Rivoli and Marengo, had some genuine sympathy with Italy - in so far as

the inhabitants wished to be freed from the Austrian yoke. But his role as "saviour of society" from Socialism made him in France

the ally of reaction, dependant on Clerical support in the country. He saw in the situation an opportunity

of combining a check to Austria with an anti-Liberal policy which would ensure for him the Catholic vote in France.

The one thing that can be truly said in excuse for the expedition to Rome is that the French Government,

when they despatched their troops, had persuaded themselves that they would be welcomed as liberators.

Outside the city, friends and foes expected that the Romans would surrender: "Italians do not fight" was the word

passed round in the French camp. But a great moral change had taken place. When on the afternoon of April 27,

Garibaldi, the long-expected, entered Rome at the head of his bronzed Legionaries from the northern provinces

of the Republic, there was little doubt of the spirit of the citizens through whom they pushed their way. "He has come, he has come!"

they cried all down the Corso. The combined effect of the presence of Mazzini and of Garibaldi in Rome

was to exalt men's hearts and minds into a region where it seemed base to calculate nicely whether

there was any hope of victory in the defensive war which they were undertaking. And in such magnificent

carelessness lay true wisdom. If Rome had submitted again to Papal despotism without a blow she could

never have become the capital of Italy.

The Thirtieth of April

Although Garibaldi was not commander-in-chief, he and no other, was recognised as leader.

Rome was then a rival to Paris as centre of the cosmopolitan artist world, both because it had some vogue

as a school of art, and because before the photographic era there was a large demand by the English and the other "forestieri"

for copies of famous pictures, and for sketches of the sights which they had come to see, and of which

they wanted some memento to take home. Garibaldi carried the heart of this Bohemian world by storm.

English, Dutch, Belgians, even one Frenchman, and the Italian artists almost to a man, enlisted during the days

that followed his arrival. Taking life and death with a light heart, they fought splendidly for Rome.

On the morning of April 29, two days after the arrival of the Legion, there marched into the city the Lombard Bersaglieri,

a regiment representing very different military and political traditions from those of Garibaldi's men, but not less

devoted than they to the Italian cause. The commander of the Lombards, the gallant Luciano Manara,

was a young aristocrat of Milan, who had distinguished himself in the Five Days of street warfare

that drove the Austrians out of his native town. After the recapture of Milan he formed a brigade out of the Lombard exiles in Piedmont and

after the defeat of Charles Albert at Novara, he sailed for Rome. The presence of these men side by side with the Garibaldians changed the

defence of Rome from the act of a party to a national undertaking.

Another element in the defence consisted of inhabitants of Rome who had had no previous experience of war,

enrolled in various volunteer bodies. The Trasteverines, their native fury now turned fully against the priests and the French,

were noticed on the morning of April 30, fierce figures with spears and shot-guns in their hands and knives

in their teeth, pouring out from their riverside slums up the steep ascent that leads to the Janiculum.

For it was against the Janiculan and Vatican hills, the defences on the right bank of the Tiber, that the attack of the French army, coming from

Civitavecchia, must necessarily be delivered. The lesser Rome that stands upon this western bank is surrounded by a line of walls comparatively modern in date;

the existing fortifications of the Vatican and Borgo were built in the latter part of Michael Angelo's lifetime,

as the result of the scare caused by the sack of Rome; while the Janiculan walls from the Porta Cavalleggieri to the Porta Portese, though

begun in the sixteenth century, were mainly the work of Urban VIII, who erected them towards the close

of the Thirty Years' War (circa 1642) (click here for a map of the Walls of Rome).

These walls, though out of date, still offered a serious obstacle to the siege guns of 1849. They sloped backwards

from the base as far as the stone line of the rampart, and their bastions had broad platforms of earth, serving to give

solidity to the brickwork of the face, and ample standing room for the batteries. But although the besieged might rejoice in the comparatively solid and serviceable

fortifications of Urban VIII, the position had one irremediable defect. The ground immediately outside was as high as the defences;

indeed the Villa Corsini was even higher than the

Porta S. Pancrazio; so that a besieger could erect batteries

at a height equal to those of the besieged, at distances only a few hundred yards from the line of defence.

This defect was guarded against by the energy of Garibaldi, who, being entrusted with the defence of the Janiculum,

saw that it must be conducted, not behind the walls, but on the high ground of the Corsini and

Pamfili gardens outside the San Pancrazio gate. He had with him

his own legion, over 1,000 strong, the regiment of 250-300 students and artists of Rome and 900 other volunteer

troops of the Roman States. The walls round the Vatican were held by Colonel Masi with 1,700 former Papal troops and 1,000 of the newly formed

National Guard.

Oudinot having left a small body to guard his communications with the sea, was advancing on Rome with some six or seven thousand infantry, and

a full complement of field guns. He had been easily persuaded by his Clerical informants that the inhabitants were waiting to open

the gates to his troops. He therefore came without siege-guns, or even scaling ladders, and advanced in column

to within grape-shot of the walls. There had not indeed been wanting signs that resistance was to be expected,

for the roads and houses were empty of inhabitants and were decorated with (ironical) notices in large type giving the text of the

fifth article of the existing French Constitution, which ran as follows:

"France respects foreign nationalities; her might shall never be employed against the liberty of any people."

The advance-guard marched straight for the summit of the Vatican hill, crowned by an old round tower of the dark ages

which served as a sky sign to guide them to the attack. Immediately under this

tower stood the Porta Pertusa, by which they were to enter Rome.

The scouts, only a few yards ahead of the column, had just reached a turn in the road where the Porta Pertusa becomes

suddenly visible, when a shower of grape from two cannon on the walls gave warning that Rome would resist. A French battery was

unlimbered on the spot, and a fire of musketry and cannon opened against the Vatican wall: but the assailants were in the open, the Roman cannon

on the bastions were well served, and no progress could be made.

The plan had been to enter by the Porta Pertusa, but, now that the time had come to blow in the gate, it

was discovered that the gate did not exist. It had been walled up for many years past, but the change did

not appear on the charts of the Parisian geographers. The attack on the obsolete Porta Pertusa had perforce

therefore to be changed into an attack on the Porta Cavalleggieri, a change of plan which involved passing down

a steep hill under a hot flank fire from the regulars and National Guard thronging the wall, and from the Roman batteries

on the bastions near St. Peter's. The Porta Cavalleggieri proved indeed to be a "gate in being" but situated at the bottom

of a deep valley, and in a retreating angle of the wall, so that its assailants were exposed to a double fire at close range

from the battlements on either side of the approach to the gate.

Meanwhile, another column and battery had started from near the Porta Pertusa to go round outside the Vatican gardens in the other

direction, with a view to obtaining an entry by the Porta Angelica,

near the Castle of St. Angelo. The motive of this false military step was political,

for Oudinot had been wrongly informed by his agents that the Clericals were in that quarter sufficiently strong to open the gate. The troops

sent on this circuitous march, prolonged by the steep descent and the bad roads, were exposed to a fire

of terrible severity, from the hanging gardens on their right flank, because the only path by which their artillery could travel at all

ran painfully close to the city wall. Under these conditions the attack on the defences of the Vatican, both to north and south, was doomed

to failure.

Garibaldi, who from the Corsini terrace had watched the French repulses at the Pertusa and Cavalleggieri gates, determined to assume the

offensive and to convert the check under the walls into a defeat in the open. To move from the Corsini and Pamfili gardens into the vineyards

on the north, it was necessary for his troops to cross the deep, walled lane, which connected the Porta San Pancrazio with the main road to Civitavecchia. Up this lane

were coming about 1,000 infantry sent forward by Oudinot to protect the rear and flank of the main attack,

and there the first clash of arms in this quarter took place. Garibaldi's advance-guard, consisting of the two or three hundred Roman students and artists, were clambering down

out of the Pamfili garden into the deep lane, when, under the

arches of the Pauline Aqueduct, they stumbled upon the advancing French column. It was the young men's baptism of fire.

Before the ardour of their attack the French at first recoiled, but discipline and numbers soon prevailed,

and the students were driven back into the garden. The enemy followed in upon their heels, and the

Garibaldian Legion was hurried up to the rescue.

A confused fight at close range ensued in which the main body of Italians was pressed back, leaving behind them small groups holding on in occupation of

various points near the Pamfili villa.

At last Garibaldi, seeing part of his Legion thus holding on in the Pamfili, and part of it driven back under the

very walls of Rome, sent into the city to call up the reserves under Colonel Galletti; that officer

marched out of the Porta San Pancrazio at the head of the Roman Legion, consisting of 800 seasoned

volunteers.

The crisis of the battle was now at hand, and the flower of the Democratic volunteers were to prove whether they could dislodge

regular troops posted behind villas and vineyard walls. Garbaldi, putting himself at the head of his own men,

reinforced by the Roman Legion, led the decisive charges by which it was hoped to recover the positions

now held by the French on either side of the deep lane. The first operation was to recapture the Corsini

and Pamfili.

Except at Tivoli and Frascati, there are few places within many miles of Rome with more of the charm

of Italy than the northern edge of the Doria-Pamfili grounds, where the heat of early summer is shaded off

into a delicious atmosphere, redolent of repose and dreams, where birds sing under dark avenues of ever-green oaks,

and no other sound is heard. Such an atmosphere make it easy to understand why Italians are in some danger of spending

their days in the too passive reception of impressions. But on this day there came Italians who had been inspired

by the moral resurrection of their country to ideals nobler than pleasure and receptiveness; who were

ready to give up the privilege of life, even of life in Italy.

Swarming over the Corsini hill, and across the little stream and valley that divide it from the Pamfili grounds, the Legionaries

came crashing through the groves. The Garibaldian officers, with long beards, and hair that curled over their shoulders,

were singled out to the enemy's marksmen by red blouses, falling almost to the knees. Behind them Italy came following on.

And above the tide of shouting youths, drunk with their first hot draught of war, rose Garibaldi on his horse,

majestic and calm - as he always looked, but most of all in the fury of battle - the folds of his white American poncho floating off

his shoulders for a flag of onset.

And so they stormed through the gardens, fighting with bayonets

among the flowering rose-bushes in which next day the French dead were found, laid in heaps together. The enemy were thrust out

of the Pamfili grounds back to the north of the Deep Lane, across which for some time the two sides

fired at one another, until the Italians finally leapt down over the wall, clambered up the other side, and carried the northern arches

of the aqueduct. Thence the Legionaries and students broke into the vineyards beyond, and after fierce struggling, body to body,

with guns, and hands, and bayonets, put the French to flight.

Garibaldi had received a bullet in the

side, and the wound caused him much pain during the next two months of constant warfare.

The afternoon was now well advanced, but the victory had been won. When a sortie was made from the Porta Cavalleggieri, Oudinot,

whose retreat from before that gate was threatened by the Garibaldian advance, hastily drew off his men

from between the two fires and made off by the road to Civitavecchia. By five o'clock, after nearly six hours' fighting

the whole French army had been driven off the field, with a loss of 500 men killed and wounded, and 365

prisoners.

That night the city was illuminated, the streets were filled with shouting and triumphant crowds, and there was scarcely

a window in the poorest and narrowest alley that did not show its candle.

Neapolitain Campaign

A quarrel arose between Mazzini and Garibaldi on the question whether or not the victory of April 30

should be turned to full military advantage. Garibaldi wished to follow it up and

drive the retreating French into the sea. Mazzini hoped to propitiate the one country whose friendship

might yet save the State, and preferred to turn the Roman armies from further pursuit of the French to the

more congenial task of expelling the Neapolitan and Austrian invaders.

The French wounded were nursed with such tenderness that Oudinot declared himself profoundly grateful; the prisoners

were set free to return unconditionally to their regiments. For the present Oudinot did not show further hostility and settled down to wait

for reinforcements. The Triumvirs could therefore spare part of the troops in the capital to meet another foe

who was now literally within sight.

In Frascati, and in Albano by the lake,

was encamped Ferdinand King of Naples, with an army of 10,000 men eager, not to assist, but to forestall

the French. The Pope, who was heart and soul with Ferdinand, thought the conquest of Rome by the Neapolitans the best security

for the unlimited restoration of clerical despotism. To keep these invaders in check Mazzini consented

that Garibaldi should cross the Campagna at the head of a small force of 2,300 troops. Since it was impossible to make a frontal attack he determined

to threaten the right flank of the Neapolitans and therefore moved to Palestrina. On May 7,

Garibaldi took up his quarters in Palestrina and started a guerilla warfare. A large force of Neapolitans was sent from Albano to drive away

the "bandit" who had become a thorn in the side of the royal army, delaying the advance on Rome and

striking terror by his mere name into the superstitious and timid southerners, dragged from their homes

to fight in a cause which was not theirs. Two columns of Neapolitans advanced on Palestrina

threatening the lowest side of the ancient walls of Palestrina at two points at once. The Garibaldians, however did not wait to be attacked,

but rushing down the steep cobbled streets of the hill-town, sallied out to give battle under the walls. They had the advantage of the hill; and the

enemy's cavalry could not charge with effect because the ground was so much enclosed. Manara in command of Garibaldi's left wing sent down

about 150 of his Lombards to meet the Neapolitans as they advanced across the ravines and up through

the vineyards, hedges, and ruins of the broken ground below the town. The Neapolitans fled, almost at once, in disgraceful rout, and the

fear of the "round hats", as they called Manara's Bersaglieri, was deeply impressed on them by this engagement.

On Garibaldi's right wing, where the main attack was delivered, the fighting was more severe, and some houses were occupied

by the enemy. The Legionaries, aided by another company of Bersaglieri, drove back the infantry, repulsed

a charge of horse on the road, attacked the houses and captured the garrisons.

The whole battle was over in about three hours, and the enemy in full flight, cast away

their muskets as they ran.

The Palestrina expedition had succeeded in its object of preventing the further advance of King Ferdinand

against the capital. In the meantime the French Goevernment had sent an envoy, De Lesseps, to come to

an accomodation with theTriumvirate and Assembly of Rome, such at least was the ostensible object. But the real motive

was to gain time. Louis Napoleon had not been so active as his Clerical Ministers in the first sending of the

expedition; but now that the honour of the army had been tarnished by April 30, his whole future as

military dictator was jeopardised until that blot should be wiped out.

De Lesseps was unaware of the ultimate goal of his master and was touched by what he saw of Mazzini and of

Rome, and declared that the Republican leaders were misunderstood at Paris. Taking advantage of the improved

relations with France, the Triumvirs sent out ten to eleven thousand of their best troops to drive the Neapolitans

out of the territory of the Republic. Garibaldi with a small force galloped out on the morning of May 19

along the Velletri road to see what the enemy were about. He found, as he had expected, that they were in full retreat

from the Alban Hils, which they had no thought of holding when their rear and flank were threatened by a force

as large as their own. The only danger was that they would escape altogether, for they were already arriving at the ancient

Volscian city of Velletri. Garibaldi determined

to take the measures necessary for cutting off Ferdinand's retreat. Finding a body of troops close to their flank,

the Neapolitans were forced to turn aside and drive it back. Garibaldi, whose scouting arrangements kept him

far better acquainted than any contemporary general of regulars with the real intention of the enemy,

knew that this offensive movement was only designed to cover their retreat. The chief incident occurred

on the Valmontone road. Masina's forty lancers had gone down it,

driving the enemy in front of them, until they met the head of a long column of mounted men before whom

they fled back at a gallop. The young Bolognese cavaliers, though noted for fearless gallantry,

were not seasoned veterans; their horses were young and untrained: they came bolting back at a pace which so aroused

the indignation of Garibaldi that, regardless of dynamics, he reined up athwart their path. Behind him sat his friend Aguyar, the splendid negro,

who had followed the Chief he adored across the Atlantic. The black giant, with the lasso of the Pampas hanging from his saddle, himself wrapped

in a dark-blue poncho, and mounted on a jet-black charger, contrasted picturesquely with Garibaldi and his golden hair, white poncho and white horse.

Like equestrian statues of Europe and Africa they sat immovable. One moment the young lancers, vainly tugging at their frightened steeds,

saw these two loom in front; the next, down they all went together in a welter of beasts and men, with Garibaldi at the bottom. The enemy's cavalry, who had some spirit,

came dashing up, and it might have gone ill for Italy, had not a handful of Legionaries, fighting at a little distance to the right of the road, come running to save their leader. The rescue

party were mostly boys of fourteen and upwards.

The Neapolitans, who had pushed forward too rashly into the heart of the Garibaldian positions, were caught between two fires, and severely repulsed, leaving thirty prisoners on the scene of the

recent cascade. Thus the incident that had begun in picturesque disaster, led to a general advance of the Garibaldian infantry through the vineyards

and down the road. Garibaldi maintained the initiative and drove the enemy up into the town.

Many of the Neapolitan soldiers had been scared by the 'red devil', whom they declared to be bullet-proof;

the giant black man behind him was Beelzebub, his father. In plaintive mutiny some cried out to their King:"You are going to

Naples, and we to the slaughter". Ferdinand ordered

the retreat to be continued. The army stole away out of the southern gate of the town, leaving its wounded

and prisoners, and retreated rapidly down the road that leads across the Pontine Marshes to

Terracina and Naples by way of the coast.

Garibaldi was convinced that Ferdinand's throne would not survive an invasion of his kingdom, and pressed the Triumvirate to allow the

army to advance. But Mazzini, even if he could regard the French as neutralised, had still to think of the Austrians, who had just taken Bologna after a gallant defence by its inhabitants,

and were fast overrunning the Romagna and the Marches. At the end of May, Garibaldi re-entered Rome

in democratic triumph.

Villa Corsini

| Villa Corsina, Casa dei Quattro Venti, | Villa Corsini, House of the Four Winds |

| fumida prua del Vascello protesa | Smoky prow of the Ship thrust forward |

| nella tempesta, alti nomi per sempre | Into the tempest, names for ever |

| solenni come Maratona, Platea, | Grand - like Marathon, Plataea, |

| Cremera, luoghi già d'ozii di piaceri | Cremera - once ye were haunts of idleness, |

| di melodie e di magnificenze | Pleasure and music and frail magnificence, |

| fuggitive, orti custoditi da cieche | Gardens guarded by blind stone statues, |

| statue ed arrisi da fontane serene, | Watered by fountains - all changed suddenly |

| trasfigurati subito in rossi inferni | Into a red infernal giddiness. |

| vertiginosi | - |

| Gabriele D'Annunzio | La Canzone di Garibaldi |

On May 31, the day when Garibaldi re-entered Rome, De Lesseps signed with the Triumvirs terms of agreement, according to which

the French were to protect Rome and its environs against Austria and Naples and all the world, but were to take up their own quarters

outside the city. In signing terms so entirely averse from the spirit and intentions of those whom he represented, De Lesseps had

sense enough to append a clause which provided that the treaty needed ratification by the French Republic.

But the home Government had already thrown off the mask, and had despatched a message putting an end to his mission.

For Oudinot's reinforcement had come to hand. The French army was again camped within a mile or two

of Rome, within striking distance of the Italian outposts. Twenty thousand men were on the spot, together

with six batteries of artillery; and 10,000 more, together with rest of the siege train and engineers, would arrive at fixed dates during the month; on June 1, Oudinot gave notice to the Romans

that the truce was at an end.

Oudinot's announcement of war, woke the Italians from pleasant dreams of chasing the Austrians out of the Appennines, to the prospect of being cut to pieces by fellow-Republicans.

Although Garibaldi was not appointed commander-in-chief he was entrusted with the defence of the west bank and it was on that side that the attack was again made on Rome.

Oudinot had thrown a bridge across the lower Tiber, and occupied the Basilica of St. Paul-without-the-walls, but he had determined not

to pass over the river in force, but to confine his main operations to the capture of the Janiculum.

It would, indeed, have been easy for him,

if he had crossed to the east bank, to blow a breach in the ancient Imperial walls as did the Italians in 1870. But the French, in 1849,

had to reckon with the hostility of the Roman populace. They knew that their difficulties would only begin when they were inside the town,

because the people would take to the barricades which they had prepared, and house-to-house fighting

would continue for days. Even if victory in such a contest could be considered certain, the price might be

the conflagration of the Eternal City. The scandal of standing triumphant on the blood-stained ruins of Rome was such as the art-loving French could dread. They therefore directed their efforts against the

Janiculum, for although it would take a little time to breach the Papal walls upon the west bank, they could be sure that, when once they had fought their way to the terrace

of San Pietro in Montorio, Rome would lie below them at the mercy of their batteries, and would have no alternative but

to surrender without further resistance.

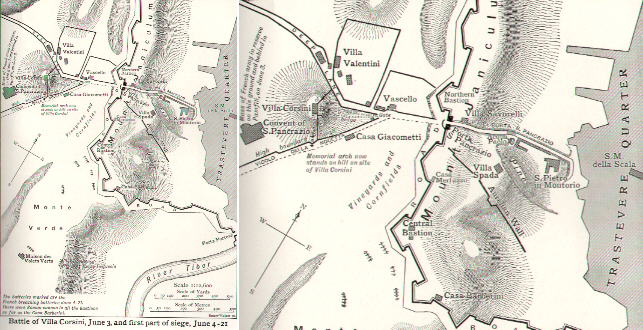

Map of the siege of Rome - June 1849

In his letter of denunciation of the armistice Oudinot had written that, in order to give the French residents

time to leave Rome, he would not resume attacking the city until Monday, the 4th of June. Notwithstanding this, on Sunday morning at dawn a French column

attacked the Roman positions at Villa Pamfili. They blew a breach in the boundary wall and the French infantry poured over the ruin, and as the morning twilight came on,

spread in wave after wave of men through the silent pine-woods that occupied the southern part of the Pamfili grounds. Meanwhile another division made its way in from the west side.

The 400 Italians were sleeping with perfect confidence in Oudinot's promise not to attack till Monday and they were soon surrounded and overpowered by superior numbers. Many escaped to

the Convent of San Pancrazio and the Villa Corsini, which stood within the Pamfili enclosure, but five or six hundred yards

nearer to Rome.

The flying men were closely followed by the French, but when the gallant Bolognese Colonel Pietramellara

organised a strong resistance in the Corsini and when troops began to pour in from Porta San Pancrazio, the Italians, being somewhat in greater force, were able to hold on.

Returning to the charge, the French regiments carried the Convent of San Pancrazio, and then, with the aid of artillery, stormed the Corsini after desperate

fighting, and drove the Italians down the hill to the Vascello. The Villa Corsini, the key to Rome, was in the hands

of the enemy.

The boom of distant cannon was heard in the city and soon everybody knew that Rome was attacked. The bells were clashing

from every campanile, and the drummers, beating the broken motif of the alarm, called men to doors

and windows down each narrow street. The city was alive with orderlies and officers dashing about to find

their regiments, making from all directions towards the foot of the Janiculum. There is a steep, shady lane,

called Via di Porta San Pancrazio, that leads the foot-passenger straight up to the gate from the low Trastevere, mounting the hill

by a precipitous path and steps. This was the quickest and for the last few hundred yards under the Villa Savorelli, the only way up

to the gate. During the whole of June it was a main artery feeding the battle on the Janiculum, and on this first eventful Sunday was filled

from dawn to dusk with soldiers and civilians hastening up to the fight, and wounded men dragging themselves down.

Via di Porta San Pancrazio seen from the gate

At about half-past five Garibaldi and his Legion arrived at the Porta San Pancrazio. As he rode through the

gateway he saw, opposite him, the Villa Corsini on its hill top, some 400 paces distant, on the site where the memorial arch stands

to-day. That house, he knew, must be retaken, or the fall of the city was only a matter of time. No price

would be too dear for it - and the price was likely to dear enough. Above the neighbouring vineyards and villas,

it rose high on the skyline, exposing its massive stone-work square to all the winds of heaven, whence it was often called the

"Casa dei Quattro Venti", the House of the Four Winds. It was four stories high, with an ornamental parapet on the top.

In front of this aesthetic fortress the ground sloped down like a glacis towards Rome, and down the middle

of the incline, from the foot of the stairs to the garden gate ran a drive bordered on each side by

a stiff box-hedge, six feet high. At the bottom of this box avenue, where outside the gateway, all the

roads met in front of the Vascello, the walls of the Pamfili-Corsini enclosure came to an end in an acute angle. Thus the

ground in front of the Villa Corsini was a walled triangle, and exactly in its apex stood the one garden gate

by which the storming parties from Rome had to pour in, if they were to get at the villa at all.

The road, up which the Italians must advance from the Porta San Pancrazio before they reached the garden gate, was completely

exposed to the enemy's fire. It was bordered on the left by cornfields and vineyards, not then enclosed by any wall; on the right of it

rose the Vascello, so called from its fancied resemblance to the shape of a ship. This, too, was an ornamental

villa of the Roman aristocracy, a rival to the Corsini in magnificence, though, owing to its situation

at the foot of the hill, it was not so prominent in the landscape.

When Garibaldi arrived the French were secure in possession of the Corsini hill, and the Italians, under Galletti, insecure in possession

of the Vascello at its foot. His regiments were sent out to pass under the fatal archways of the Porta San Pancrazio, and rush up the road at the Corsini. In the open road sat

Garibaldi on his white horse, amid his rapidly dwindling Staff, sending up one division after another of his Legion to dash at the garden gate

of the Corsini, pour through its narrow entrance, rush up the slope by the line of box-hedges, under a fire from every

window of the façade, till the survivors reached the foot of the steps. Then, if enough were left, they would storm up

the double staircase, gain the balcony, bayonet the French in the drawing-room, and stand for a few minutes master of the villa.

Several times the Corsini was carried, and held for awhile, against the concentrated fire of a whole army in the woods

of the Pamfili beyond.

The French were in huge force and Garibaldi as yet had scarcely 3,000 men with whom to line

the wall of the city and make the attacks.

The Bersaglieri arrived at about eight o'clock when the Corsini had just been lost once more, and the French

were pressing down along the box-hedge to attack the Vascello, whose gardens and windows

were raked by a fire from the Corsini hill. Thus pressed by the concentrated fire of the French positions and

the advance of large bodies of regular troops, the Legionaries, who had lost immensely, both in officers and in men,

were only held to their posts by the inspiration of Garibaldi's presence. The Bersaglieri officers found him

in the thick of the fire, his white mantle riddled with bullets, but himself miraculously untouched, spreading calm and

courage wherever he appeared.

Garibaldi at the arrival of the Bersaglieri sent one of their companies to occupy the Casa Giacometti, a small,

but high and strongly built house, from whose windows the troops could fire over the wall into the Corsini gardens

and the windows of the villa. Having thus checked the French advance and prepared a protection for the

storming party he told Manara to capture the Corsini.

With loud cries of "Avanti! Avanti!" three or four hundred of the finest men of north Italy, led by Manara

himself and Enrico Dandolo, poured under a storm of bullets, trough the narrow gateway, where scarcely five

could pass abreast, and spreading out to to right and left of the box-hedges rushed up the slope - their Bersaglieri plumes streaming behind.

But the French who now were massed in the villa and along the orange-tree wall, not being subjected

to any considerable covering fire, moved down the Italians so thickly that, at thirty paces from their

goal, the assailants halted; instead of retreating, they deliberately knelt down on the open slope and opened fire at the hidden

Frenchmen, while the officers stood behind the kneeling men and partook of the massacre. Among others, Enrico Dandolo was here

shot dead. For ten minutes Manara watched the slaughter of his men before he sounded the retreat, and until

the bugle was heard not one had flinched. Then began the return down the slope and trough the gateway.

The catastrophe was fatal to any feeble chance of victory which the Italians may have had that day. Now Garibaldi

caused the gunners on the walls of Rome to turn their full energies against the Corsini façade, from which large

ruins ere long began to fall while the Bersaglieri posted in Casa Giacometti kept the Corsini windows under a constant fire.

Throughout the long mid-day heat the battle settled down into a heavy cannonade and musketry-fire on both sides. The Italians

held the Vascello and Casa Giacometti, supported from behind by their batteries on the wall.

Well on the afternoon the French fire slackened, in consequence of the terrific effect of the cannonade

on the villa.

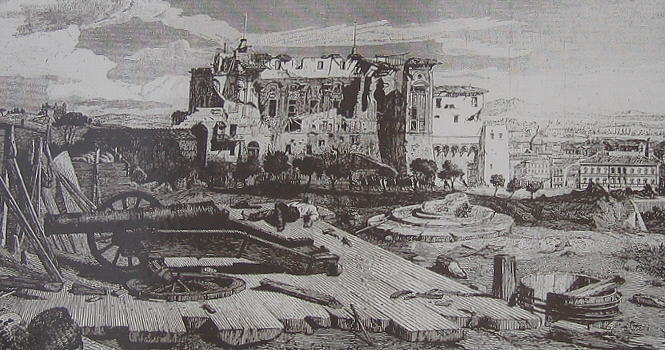

Villa Corsini after the Italian cannonade

(engraving by Carlo Werner)

Garibaldi seized the opportunity to launch another attack, headed by Masina's forty lancers

in the capacity of dragoons, armed with muskets. The horsemen raced through the garden gate and up the slope and, amid frantic cheers from the Italians crowding the battlements of Rome, followed Masina in his last

wild gallop up the steps of the Corsini.

Meanwhile the infantry, pouring out of the Vascello, were following close behind the horsemen, Manara

and Garibaldi urging them on. At the point of the bayonet they cleared the Corsini hill of the last Frenchmen,

and proceeded to occupy it in force.

Romans watching the fight at Villa Corsini from Porta San Patrizio

(detail

from a painting by Léon Philippet - Museum of Ville de Seraing - Belgium)

And now another wave of men came rolling up from the gate of Rome. The spectacle of Masina charging up the

steps, the capture of the Corsini, and the evident arrival of the final crisis of the day, had been too much for the

discipline of the watchers on the walls. A maddening enthusiasm, akin to panic, although its opposite,

seized the crowd of citizens, artists, gunners, and the infantry of the spent regiments; flooding through

the Porta San Pancrazio they swept along the road to the villa in a dense mass. When the mob reached the esplanade

of the ruined Corsini, they joined in the hasty preparations for the defence. The unregimented men,

who showed much goodwill and promptness, were got into some kind of order, and made to lie down among the brushwood,

awaiting the French attack from the Pamfili. Oudinot's well-arrayed army, regiment behind regiment,

could be seen coming forward through the pine trees, which were throwing long shadows in the

evening light. The defence was well maintained for a short while, and the French lost severely in their advance;

but they pressed on with ever fresh men and finally reached the crown of the hill. The Italians fell back,

still firing, from the Villa Corsini, which had proved, not impregnable, but untenable.

The last to ride under the sheltering door of the Vascello was Garibaldi, whose face and bearing betrayed

no emotion at the final destruction of his hopes. Behind him Manara closed the door. In the confusion, Masina had been left behind. It is not certain

at what spot on the steps or in the garden of the Corsini - at what moment of the advance or retreat - he fell; his body was left lying in the middle of the

slope, sixty paces from the steps up which he had so gallantly charged. During the rest of June, the Italian

bullets from the Vascello, and the French cannon-balls from the Corsini, sang day after day over his

whitening bones, which only after Rome had fallen was it possible to seek and bury.

Dusk had already fallen, when Garibaldi directed a last vain attack against the now shapeless ruin on the hill top. In this period of the battle

fell Goffredo Mameli, the Genoese boy-poet, whose war-hymn was on the lips of these warriors (Note: Fratelli d'Italia - Brothers of Italy - became in 1946 the national anthem of the Republic of Italy).

So ended the Third of June, which sealed the fate of Rome. On the same day, four miles to the north, a less important operation had taken place on the upper

reaches of the Tiber, across which the French secured a passage by capturing Ponte Molle.

The chief glory of the Third of June does not belong to Garibaldi, but to the slain - the seed that had fallen into the ground and died, and was to bring forth fruit in its season.

The Siege of Rome

The heroism shown by the Italians on the third of June was no spasmodic outburst of rage on

the part of a race incapable of sustained valour. For nearly a month to come the regiments which had been

decimated in the attacks on the Villa remained at the front, under fire every day and during many nights,

exhausted in nerve and muscle by the unrelieved strain of siege and bombardment, repeatedly

engaged in the fiercest hand-to-hand fighting, losing, one by one, the remainder of their officers, but still

maintaining positions which, according to the ordinary maxims of the military art,

had been rendered untenable by the erection of French batteries in front of the Corsini.

The French army, rapidly increased to 25,000, and, towards the end of the month, to 30,000 men, was supported

by a train of siege guns and a fine corps of engineers. The Italian artillery extorted the praise of their

enemies by their astonishing courage and the accuracy of their fire.

The Vascello formed an advanced line which Garibaldi had, on the evening of June 3, entrusted to the charge

of the Milanese Giacomo Medici, who had arrived in Rome from the North with a "Medici Legion" some three

hundred strong, students and young men of wealthy Lombard families. With his own legion, aided from time to time by detachments

from Manara's Bersaglieri, and the Students, Medici held the Vascello having established communication

with the San Pancrazio gate whence he drew his supplies. Day and night the French waged war on this Italian outpost; the enemy fired down

into the garden and windows of the Vascello, while their trenches were pushed ever nearer and nearer. Attacks were made by night

at the point of the bayonet, and a battery pounded the Vascello walls to pieces at a range of about 200 yards. Under these conditions the Vascello

was still untaken on June 30, when its heroic defenders retreated out of the ruins because the walls of Rome had been captured behind their back.

The unexpected resistance of this outpost delayed the fall of Rome by many days, because it prevented the French from pushing their trenches

forward against the face of the Porta San Pancrazio. But the occupation of the Corsini enabled the French

to reduce the Janiculum gradually from its south flank by opening trenches against the Centre Bastion and that of the

Casa Barberini (Villa Sciarra).

The high Villa Savorelli, towering above the Porta San Pancrazio, had been selected

by Garibaldi as his headquarters because, though exposed to the enemy's fire, it commanded

a wider prospect of the Italian and French positions than any other house

within the Roman walls.

Villa Savorelli and the Italian battery near Porta San Pancrazio

(engraving by Carlo Werner)

When the French bombardment began, the Savorelli gradually crumbled beneath the cannon-balls;

it had been riddled through and through before the staff, on June 21, thought of moving elsewhere.

Garibaldi constantly went the rounds, visiting the places where the

fire was hottest, and restoring the enthusiasm of the defenders, now by a word of

personal sympathy, now standing like a statue above his prostrate companions while a shell

was bursting in their midst. He seemed to disregard death as a weak thing that he knew

by old experience had no power to touch the man of destiny before his hour. That sentiment was

now deeply implanted among his best men. Their hearts beat high, but not with hope.

During the first seventeen days and nights of the siege (June 4-21), while the zig-zag of the French

trenches was creeping nearer hour by hour, and the batteries erected under their protection

were gradually crumbling the breaches in the bastions, the defenders made many sorties, which proved

not very effective. On some occasions the greatest gallantry was shown by the sortie parties, as when

a detachment continued to maintain the fight with stones after their ammunition was exhausted. The Poles,

too, conspicuous for their long moustaches and their national cap, with its four-cornered crown

of red cloth, were foremost in seeking death; homeless sons of the slain mother, they generously

offered their blood on behalf of any nation that was at war with tyranny.

On June 21 the French fire became hottest against the Central and Barberini Bastions, where a

furious cannonade and musketry fire, maintained from the trenches now within a few yards of the wall,

only ceased at nightfall when the crumbling breaches presented an easy slope for the assailants to mount. That night the enemy were masters

of both bastions.

The French enter through the breaches

(contemporary print)

The Italians feared that if the French pressed on at once in force they might carry the

Savorelli and San Pietro in Montorio before daylight, and so finish the siege. Garibaldi saw the

danger and, instead of attempting the impossible recapture of the lost positions, he devoted

himself to fortifying and manning a second line of defence along the old Imperial wall of

Aurelian, and when day dawned the new position was strongly occupied, and the fear of a capture

of the Janiculum by a coup de main was at an end.

The second part of the siege of Rome - the nine days' defence of the Aurelian wall (June 22-30) -

surprised the French and even the Italian themselves, who could scarcely believe their senses

when they found each morning that the enemy had not yet stormed their untenable positions. Now that all

was lost, the idea of perishing with the murdered Republic seemed to fortify the morale

and brace the nerves of the tired men, whose conduct became now more uniformly heroic than

it had been during the fortnight past, when it was still possible to indulge a shadowy hope.

The scene of the last struggle was worthy of the actors and of the cause. On the high ground

where the Savorelli stood down to the Trastevere ran the wall built by the Emperor Aurelian

to keep off the trans-Alpine barbarians when Rome's grasp of the world was growing weak;

behind what here remained of it lay Garibaldi's infantry. Their cannon were planted in the rear,

to fire over their heads from the platform of San Pietro in Montorio. Between the batteries on the height

and the infantry below along the walls, was the

Villa Spada, now Garibaldi's headquarters,

standing by itself in its small garden.

The French guns erected on the captured breaches fired across the wide open space and valley

that divides the Villas Barberini and Spada, while the batteries near the Corsini enfiladed

the Italian line from the west. For eight days the cannonade and musketry fire raged continuously.

The accuracy of the Italian gunners surprised the French and retarded their attack; the shells

tore holes in the Spada, and exploded among the staff officers in its rooms. The roof of the church

of San Pietro in Montorio collapsed. Nearly all the Italian gunners were killed or wounded. The

men of the Garibaldian Legion and of Manara's Bersaglieri, with indefatigable zeal

remained at sentry work for seventy-two hours at a time, and, with utter disregard of death,

laboured in the open to pile up again the frail defences as they crumbled beneath the fire.

On June 26, Anita Garibaldi suddenly appeared in the doorway of the shot-riddled Spada, and

her husband, with a cry of surprise and joy, sprang into her arms.

She had found her way from Nice into the beleaguered city before he even knew of her intention

to start upon a journey which he would not have approved.

Outside the walls of Rome the storm beat with still greater fury on the Vascello. From the Corsini

hill, a battery of half a dozen guns fired on it day and night, throwing into it not less than

four hundred cannon-balls, besides shells and grenades. It was owing to the protracted

resistance of the Vascello that Rome had not fallen many days before. At length, the greater part

of the vast building fell with a roar, amid a cloud of darkness, like a bursting volcano.

A score of its defenders were buried under the ruins, but the rest, sheltered by portions of

the ground-floor still left erect, came out covered with dust, and were quickly reposted among the fallen

masonry to resist attack. At night the French fell upon them from every side. For three

hours the battle raged over the rubbish heap of what had once been a magnificent villa. At dawn

Medici was still in possession. Rome might be taken, but not the Vascello.

Meanwhile, within the walls, the defenders of the Janiculum endured, day after day, the last terrible

cannonade, and the other parts of the city did not altogether escape. Not only were the inhabitants

of Trastevere driven in crowds from their ruined houses, but the bombardment did injury

on the Capitol, and elsewhere in the

very heart of Rome. As early as June 25, Oudinot had received a protest against the destruction

of private properties and works of art, and the death of peaceable citizens, signed by the

consuls of the United States, Prussia, Denmark, Switzerland, and Sardinia, at the instigation

of the British Consular agent, whose name appeared at their head.

While the city below was suffering more or less severely, the defences on the Janiculum

were crumbling fast beneath a storm of missiles. It was clear that, in spite of the heroism

of the defenders, the French would, in a few days at most, be able to storm the line

of the Aurelian wall. Garibaldi vainly urged that the Government and army should migrate

from the capital, and continue the national war to the last in the mountains

of Central Italy or of the Neapolitan kingdom. Mazzini had perhaps a higher rationality

on his side when he determined that the irrational defence of the walls of Rome

should be continued to the very last. Garibaldi, finding his advice rejected, on the evening of June 27

threw up his command and carried off his myrmidons of the Legion from the Janiculum

to the lower town. Manara hastened down to find Garibaldi and exposed to him the fatal consequences

of his behaviour. Garibaldi listened to his new friend, repented and returned

to his post, amid the cheers of the populace, and to the intense joy of the defenders

of the Janiculum.

When, at daybreak of June 28, the Garibaldian Legionaries returned to the Janiculum

with their chief to share the last slaughter, the welcome they received was all

the more enthusiastic because their rank and file on this occasion appeared

for the first time in the famous red shirt, which had hitherto distinguished

the General's staff. Indeed, many people, ignorant of the crisis that had been averted,

supposed that the Legion had gone down to town only to change the old for

the new uniform.

The Fall of Rome

The end was now at hand. The French artillery were victors in the duel which both sides had waged

so gallantly for more than a week past.

The night of June 29-30, the Feast of St. Peter and St. Paul, was selected by Oudinot

for the final assault. During the earlier part of the night the festa was celebrated

in the town in right Roman fashion, with lighting of candles in the windows , and sending up

of rockets in the streets, and the dome of St. Peter's blazed with every extravagance

of colour. The French officers, as they stood in front of their dark columns, waiting for the

signal to mount the breach, saw below them the holy city glowing "like a great furnace, half-extinct,

but still surrounded by an atmosphere of fire". Suddenly the heavens were opened in wrath,

and a deluge of rain fell on the disobedient children of the Pope, extinguishing their

last poor little fires of joy. But the Italians watching on the Janiculum were in no humour

for the child's play that amused their compatriots below. Scarcely more than four thousand

now remained of the men under Garibaldi's command. Their reserve was posted on the central height

of San Pietro in Montorio: from that point to the Porta Portese the Trastevere quarter was lined

with troops; the Villa Spada, which, though half in ruins, was still the headquarters,

was strongly occupied by Manara and a part of his Bersaglieri; the battery near the Porta

San Pancrazio was entrusted to the Garibaldian Legion, and to the remnant of Masina's

cavalry, dismounted and armed with their lances for hand-to-hand fighting.

To both sides the long delay in the attack caused by the storm seemed an unbearable

suspense. At length, more than two hours after midnight, the French columns were let loose.

The rain had stopped, but the night was dark as a grave. The French rushed up the breach under

a heavy fire from the Bersaglieri, and after a severe struggle overpowered the defenders

of the bastion. Meanwhile a second column of French, starting from the Central

Bastion captured ten days before, passed along the inside of the walls of Rome, till

they came to the line of the Aurelian wall, which they stormed at the point of the bayonet.

Once within the lines of defence, this second French column obeyed admirably, in spite of the

darkness and confusion, the elaborate orders which it had received. One part turned wheeled to the

right, and rushed towards the Spada; while another part went forward to the left to capture

the battery beside the Porta San Pancrazio. The French charged along the inside of the

trenches, driving before them all the Italians they found there, until pursuers and pursued

dashed up against the garden gate of the Spada, which Manara and his Bersaglieri turned

to defend. Not being able in the darkness to tell friend from foe, they reserved

their volley until they could distinguish at a few yards the epaulettes which marked

the French uniform; then the Bersaglieri fired with terrible effect and the French

attack recoiled.

Garibaldi himself was no longer in the Spada. Starting up at the first alarm, he had

sprung out, sabre in hand, crying: Orsù! Questa è l'ultima prova.

("Come on! This is the last fight."). There was need of him outside, for the first onslaught

of the French columns had put to flight many of the Italians. At this crisis, when a

disgraceful catastrophe was only too probable, Garibaldi and a few gallant men behind him

flung themselves headlong on the victorious French, and checked their career. Inspired

by the presence of their chief, the runaways turned back, and "the last fight" was worthy of the siege

of Rome. In the thick of the melée he sang and struck about him with his heavy cavalry

sabre, which next day was seen to be covered with blood. Behind him the red-shirts pressed into

battle. Along the road in front of the Savorelli, and in the battery near the Porta San

Pancrazio there was a swaying mass of men killing each other with butt and bayonet, lance

and knife.

On such a scene came up the golden dawn, and there in the fresh morning were Soracte,

and Lucretilis, and the Alban Mount, again as of old.

With the first light the Italians re-occupied the line of the Aurelian wall and the

road in front of the Savorelli, but the French were already fortifying the bastion next to Porta San

Pancrazio. At these close quarters a furious cannonade and musketry fire, varied

by spasmodic charges of infantry, continued throughout the early morning. The French batteries

renewed their bombardment of the Spada and the Savorelli, while the fire of the infantry

from the newly captured bastion raked the Italian lines. The defenders' cannon were now silent.

Most of them were lying overturned, among the corpses, with their wheels broken, and the

battery near the Porta San Pancrazio was in the hands of the French. Seeing that the city gate

might be taken at any moment, Garibaldi at last recalled Medici and his gallant

comrades from the ruins of the Vascello, which the army of France had failed to take by

assault.

The last resistance of the Bersaglieri at Villa Spada

(engraving by Carlo Werner)

The principal efforts of the French on the morning of June 30 were directed to make the Spada

untenable; and within its walls the tragedy of Manara and his

Lombard regiment was fulfilled. The last scene in the little villa must always be described

in the words of Emilio Dandolo, who was taking his part in the defence:

"Villa Spada was surrounded; we shut ourselves into the house, barricading the

doors, and defending ourselves from the windows. The cannon-balls fell thickly,

spreading devastation and death. It is maddening to fight within the limits of a

house, when a cannon-ball may rebound from every wall, and where, if not thus

struck, you may be crushed under the shattered masonry; where the air, impregnated with

smoke and gunpowder, brings the groans of the wounded more distinctly on the ear, and where

the feet slip along the bloody pavement, while the whole fabric reels and totters

under the redoubling shocks of the cannonade. The defence had already lasted

two hours. Manara passed continually from one room to another, seeking to reanimate

the combatants by his presence and words.

At one point he was standing at an open window, looking through his telescope at some of the

enemy who were in the act of planting a cannon, when a shot from a carabine passed through his body.

"I am a dead man," he said, falling; "I commend my children to you". The surgeon hastened

to his assistance. I looked inquiringly into his countenance, and, seeing

him turn pale, lost all hope. He was laid on a hand-barrow, and, taking advantage

of a momentary pause in the firing, we passed through a broken-down window into the open country."

Still, after their chief had been carried off to die, the Bersaglieri continued the defence

of the villa, till almost everyone inside its walls had been wounded.

Finally, when the ammunition was running low, Garibaldi headed a last desperate charge

against the French positions. Again, as on the night before, it was cold steel, and

again Garibaldi fought in the front, dealing death with his sword, reckless of his life,

and against all the chances remained unscathed.

A truce was arranged at mid-day for the gathering of the dead and the wounded, and Garibaldi

was summoned to the Capitol, where the Assembly was discussing the question of surrender.

Although the ruins of the Spada had not been stormed, all knew that Rome had fallen.

After lengthy discussions and against the advice of Garibaldi and Mazzini, the Assembly passed

the following resolution:

"In the name of God and the People: The Constituent Assembly of Rome ceases from a defence

that has become impossible and remains at its post". The French agreed to make their entry on July 3.

Today

A gigantic statue of Giuseppe Garibaldi at the top of the Janiculum celebrates the 1849 defence of Rome.

Villa Doria Pamfili: it suffered only minor damage because of the fight: the Prince Doria erected in the gardens

a round temple dedicated to the French dead.

Villa Corsini: entirely lost: on the hill

where the villa stood, the Pamfili erected a gigantic arch.

Villa del Vascello: only some walls of the ground floor were spared and can still

be seen in the state they were in June 1849.

Porta San Pancrazio: it was entirely rebuilt with a different design by Pius IX: its long inscription

celebrates the French victory and the return of the pope.

The site of the main breach restored by Pius IX

Walls of Pope Urban VIII: they were restored by Pius IX who put a papal emblem with the year

1849 on the parts which were rebuilt, which are also identified by white stones marking the

limits of the breaches.

Aurelian Walls of Trastevere: entirely lost

Villa Savorelli (Casino Farnese sul Gianicolo): it was rebuilt in line with its former design.

Villa Spada: it was rebuilt as it was.

Inscriptions celebrating the same event (Italian - the glorious defence - left) (Papal - the glorious conquest - right)

|

|

Garibaldi's Defence of the Roman Republic

Garibaldi's Defence of the Roman Republic