In the Wake of Sheltowee

part

one

Farewell,

farewell to you here

you

lonely travellers all

the

cold north wind does blow again

the

winding road does call.

-Fairport

Convention

(trad.)

Monday November 12

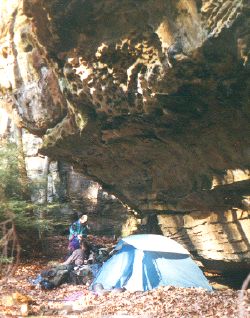

Under an overcast sky, six of us made our way, winding north along a narrow groove in the Cumberland plateau cut by Thompson Creek. Descending back in time thousands of years with each step, the strata we are moving through was laid down some 300 million years ago, in the late Carboniferous, when this area was repeatedly submerged, swamped, beached, and forested as part of a shifting coastline. The trail passes a few small waterfalls along a narrow ledge under overhanging sandstone rock shelters. These shelters were used by hunters as early as 12,000 BC with some evidence of occupation dating back almost 20,000 years. Foxes have dens, birds have nests, the son of man has rockhouses.

Mist floats through the pines and oaks, this years leaves already covering the forest floor, sky threatening to drizzle as the trail gently descends along the edge of the plateau, evergreen rhododendrons above and below gorge walls and boulders of grey sandstone. Dondrub with the lightest pack, bringing up the rear, chanting aloud, letting all the animals know he was coming; fair enough. Samten overheating in his polartec. Gyatso walking like her feet already hurt. Jenny and Marc out ahead with enough youthful energy to make it look easy. Six moving through the woods.

A few hours into it we broke for a quick lunch at a creek junction and looked at the map. After fueling we forded a creek and scouted out the orange trail, as previously indicated. Once Jenny and I found it, we waited for a few moments, tightened our shoes, and hiked on. We soon crossed water once again, looking back to make sure Gyatso saw where we had gone before heading northeast along the southern bank of Rock Creek. The trail cuts through the northwest corner of BSFNRRA and soon crosses the Tennessee/Kentucky state line.

Here is the true southern entrance of the Sheltowee Trace. Dedicated on June 23, 1979, the trail runs northeast for almost 270 miles across eastern Kentucky to within about fifteen miles of the Ohio River, skirting along the western edge of the Cumberland Plateau at elevations ranging from 700 to over 1600 feet. The rocks visible on the southern end are sediments from the Pennsylvanian era, laid down on the edge of a shallow sea between 286 to 320 million years ago.

As a result of the pressure created by the African plate ramming the coast of Carolina zillions of years ago, the Plateau block faulted and lifted over 2000 feet above sea level, generally discharging to the northwest. While the eastern edge presents a solid wall, impassable for many miles, the western slope is unevenly broken and well drained with some deep canyons and waterfalls. This is the upper watershed of the Cumberland River. From here west, the layers that make up the Pennsylvanian sandstones on the upper surface have been eroded away by water, cutting steep grooves in the western slope. In the streambeds of deeper canyons, the action of water is exposing the upper layers of Mississippian limestones. On the western extreme of the plateau, the upper layers have eroded away altogether, leaving Mississippian strata exposed. This is the region known as the Highland Rim. This 'rim' is relative to depressions such as the Nashville and Blue Grass Basins which represent some of the best farmland in Tennessee and Kentucky. These basins underlie the Carboniferous sediments and were dug out by a convergence of river valleys over millions of years, exposing fossils from the Ordovician period. Nashville is 400 feet above sea level in a pocket of good soil surrounded by the limestones of the Rim. South and west of the Nashville Basin, the fields and forests of the southern highlands drop off toward the Tennessee River valley.

On the westernmost extension of Elk Ridge, the last highland remnant running across southern middle Tennessee, the crown of Turtle Hill rises 600 feet higher than Nashville, 800 feet lower than the cliffs overlooking the main gorge of the Big South Fork, and about 400 feet lower than the river at Angel Falls. The dendritic drainage patterns on the Highland Rim are as intensively lobed as those found throughout the plateau, although in more moderate relief. On a topographic map, the visual effect is like a mosaic of white oak leaves.

After the fordings, the path ran straight, sometimes following an old

logging road along a nearly flat shelf through the tangled bottoms. In

the valley cut by Rock Creek no breeze blew. Between the competition among

big trees for canopy, the afternoon sun already behind the wall of the

gorge and the overcast sky, it was powerfully dark and quiet. Jenny and

I were able to maintain a good pace for an hour or so before it began to

rain lightly. Stopped and waited under a dense Hemlock. Gyatso shuffled

up in her rain gear. Mark followed. It soon grew dark and the rain fell

harder so we decided to pitch tents while we were relatively dry, staking

them right near the trail so that anyone passing by could not miss them;

but Dondrub and Samten never showed up that evening.

It rained and snowed and neither of them had a tent. This had never happened

before.

Tuesday November 13

1864: Hood establishes his base at Florence

The next morning, the four of us rolled up wet gear, slipped into Gortex and slowly continued north. We were moving through the mist when we hailed up some fellows hunting wild hogs on the opposite bank. They were very friendly, and obviously local boys enjoying their jaunt in the woods. Their prey, Russian wild boar, is believed to have descended from pigs escaped from a North Carolina estate during a forest fire in 1910. Signs of their presence can be seen on sections of the path that have been thoroughly dug up for roots, like someone had come through with a rototiller.

An owl hooted from a side hollow and we spooked some grouse before passing an open area with picnic tables, set out on the other side of Rock Creek. No one was camped there. Still fairly dark and wet down here. Even on a clear summer day, the depth and angle of the groove we move through only allow direct sun to shine into the bottoms for a maximum of five hours. I am reminded of an apartment where I lived for a short stretch on 85th St. in Manhattan that got a maximum of three hours sun as it passed through an alley between the fire station and a funeral parlor in the afternoon. A look at the map revealed the nearby clearing as Great Meadow campground and a good road led down to it. I thought about how Samten and Dondrub might have fared overnight and wondered if they had made it back to the truck yet. I later learned that less than an hour after we had passed this point, they actually drove down to Great Meadows, where Dondrub belatedly waded across Rock Creek and left a note for us in the middle of the trail.

More rain on and off as we pass under great American Beeches, a half

dozen species of Oak, path regularly turning up and into the hill to get

across a trickle of a brook and then back out and down again, moving among

the ever present trunks of Tulip Poplars and Hemlocks racing skywards,

thick on the lower slopes throughout this valley. At day's end we ascend

on a trail of ice and then mud, slowly crawling up out of the valley, catching

direct sun for the first time since we'd said goodbye to the Khenpos.  Camped

on a leafy shelf at the base of sandstone cliffs. Jenny was cold and wet

and immediately crawled into a sleeping bag to warm up while we fetched

water and prepared dinner. We talked quite a bit that day, on and off,

about the nature of good communication, noting that it is one thing if

we are sitting around the living room and someone doesn't listen carefully

to what gets said; if someone is spaced out, it may not seem like a big

deal, maybe even amusing. But if you're not paying attention out here,

you can end up in a totally different part of the forest or worse. The

woods are a perfect matrix in which to retreat and practice mindfulness

in relationship, to weave and test the fabric of community, at least insofar

as we are much more dependent on each other and must learn to communicate

or deal with the consequences. Of course, there are many things we can

do, individually and together outside of spending more time in the woods,

but this format gives us time for things to develop, to observe and to

live things out together in a natural medium. Marc shares his heart and

vision. He speaks of learning how to cook well, so he can prepare good

food for the Sangha. More converse about preparing the mind for these excursions

by studying books and field guides on animal prints, birds, wildflowers,

geology and trees, developing a deeper appreciation for what we're seeing

here. Don't limit yourself to Dharma texts; embrace learning. Read all

kinds of books, continually pursue studies in many areas of interest to

gain more insight into the way different aspects of the world work.

Camped

on a leafy shelf at the base of sandstone cliffs. Jenny was cold and wet

and immediately crawled into a sleeping bag to warm up while we fetched

water and prepared dinner. We talked quite a bit that day, on and off,

about the nature of good communication, noting that it is one thing if

we are sitting around the living room and someone doesn't listen carefully

to what gets said; if someone is spaced out, it may not seem like a big

deal, maybe even amusing. But if you're not paying attention out here,

you can end up in a totally different part of the forest or worse. The

woods are a perfect matrix in which to retreat and practice mindfulness

in relationship, to weave and test the fabric of community, at least insofar

as we are much more dependent on each other and must learn to communicate

or deal with the consequences. Of course, there are many things we can

do, individually and together outside of spending more time in the woods,

but this format gives us time for things to develop, to observe and to

live things out together in a natural medium. Marc shares his heart and

vision. He speaks of learning how to cook well, so he can prepare good

food for the Sangha. More converse about preparing the mind for these excursions

by studying books and field guides on animal prints, birds, wildflowers,

geology and trees, developing a deeper appreciation for what we're seeing

here. Don't limit yourself to Dharma texts; embrace learning. Read all

kinds of books, continually pursue studies in many areas of interest to

gain more insight into the way different aspects of the world work.

Wednesday November 14

Morning sunshine was drying out the woods as we stopped to view the drainage basin sloping down through Dry Branch of No Business Creek. It all flows generally east from this ridge and empties into Big South Fork. Mist hangs above the trees at the river's edge as sunshine fills the valley. It is still early, but being already sweaty from the trail, we linger at the overlook and consider removing packs and taking off longjohns, but are quickly convinced to drop that idea by a cold breeze; it is obviously much too cool to stop here in the damp shade and we move on. Soon we come upon Gobbler's Arch, a small span of sandstone in the sunny woods on top of a ridge apparently known for its big bird population.

The smell and feel of the woods is enlivening. Simply to move the body with a conscious load becomes meditation. Gaining a natural balance under the new weight, attentive to foot placement, breathing deeper as we begin to find a pace, adjusting hip belt, loosening the chest strap. Much of the time on the path is spent in silence, sometimes because we are spaced far apart, or walking in single file where it is difficult to be heard, but usually just as part of the economy of the trail. The yoga of dealing with the body under stress, the exhilarating rhythm of breath, heartbeat, and flowing vision, the jangle and momentum of the pack, all tend to minimize conversation. Repeating mantra, identifying brown leaves by shape to know what kind of woods we're walking through now. Woodpecker's jungle call and roll in the distance. Looking for the next turn of the path, the sodden leaves leading up over the next rise. Many kinds of fungus on trees both living and dead, strange colorful growths, none of which I can name. The mind floats around the next bend, the body follows. It was Old Jim who taught me the backpacker's prayer, years later: Lord, you pick 'em up, I'll put 'em down. When vision gets limited to the step immediately ahead of me, intensively studying the ground for some pattern which would indicate fossil or artifact, mindlessly counting steps, too hot, thirsty or far ahead, it is probably time to break. On the average, we stop once an hour, sometimes simply standing and sharing water but more likely removing packs, if not shoes, and sitting down for a few minutes.

The land repeats a basic pattern of gently rolling ridgetops which are high and dry with stands of Virginia and Pitch Pine above gorges which tend to be narrow, wet, and often have clifflines and rockhouses on their upper margins. Waterfalls, springs and seeps are all common on the way down. So are huge boulders which have fallen from upper cliffs while the path occasionaly snakes through a mossy tumble of giants. Hemlocks like the cool slopes and will often be found toward the bottoms along with smooth grey Beeches and the pale yellow and scaly browns of water soaked Sycamores. There is not much breadth of vision in here. One is either in the groove or on top of it, and once away from the gorge and in the rolling woods atop the table, there is nothing especially remarkable to be seen from afar. Much of our day is spent observing things at short range, distances within a few feet or a few dozen yards. Even if you were to climb a big tree to see further from a high ridgetop, you would behold no more than a rolling sea of treetops stretching from horizon to horizon, with no mountains rising into the sky beyond. And this is exactly what you will see looking out from the top story of the pagoda which will one day rise up through the tallest trees on Turtle Hill. Here on the plateau, the occasional overlook from a cliffline is always a special thing and often a tempting place to hang out for awhile. We never pass up one of those without thinking about it carefully and evaluating our time and intention in being out here at all.

In spite of the seemingly endless repetition of natural forms, it is no exaggeration to say that every turn of the path holds another surprise; more wildflowers we will have to look up, half a dozen waterfalls, an exposed seam of coal, the flutter and general chaos when a Tom and his harem are spooked by our sudden appearance into a protected cove; here, golden lichens grace the lower skirt of a great boulder long ago fallen from the upper cliffs; laying in silence below entire trees which have rooted themselves in the layer of soil accumulated on its upper surface; wild grape vines thick as my upper arm hanging from high in the canopy, another just as fat, clinging to the trunk of a well established Red Oak. Regularly scanning for perceptual markers revealing growth habits and fallen leaves, burrs or nuts which might aid in recognition or hint at a name.

The Appalachian uplands contain the most diverse forests in the temperate zones; only tropical rain forests have more kinds of trees. 178 tree species are native to Tennessee, and several introduced species now grow wild. The Oak - Hickory complex makes up about 72% of the forested area. Almost 90% of the trees in Tennessee forests are hardwoods with Oaks dominant, White oak (Quercus alba) being the most common. Pines are next most common, then Hickories and Yellow poplar. Currently, the Volunteer State leads the nation in production of hardwood lumber, hardwood flooring, log homes, and are you ready for this? Pencils. Wood delivered to mills is one of Tennessee's three highest-value crops, along with soybeans and tobacco. Half of Tennessee is forested (13.3 million acres).

Unfortunately, new products such as chip board, fiberboard and paper made from hardwoods are increasing the demand for low quality hardwoods throughout the south. There are about 140 chip mills currently operating in the southeast and about 100 have been built in the last 10 years. High capacity mills can chip as much as 300,000 tons or about 18,000 acres of trees per year. Most of the forested land in the state is held by individual property owners. This means that if the folks who own the woods don't make intelligent decisions, these mills could seriously degrade the quality of forests on the Cumberland Plateau in a very short period of time. Current these chip mills are consuming about 1.2 million acres of forests annually. Kentucky has a little over 12 milllion acres in trees, so that's equal to about one tenth of Kentucky's total. Tennessee has 13 million acres. A single mill can turn 100 or more truckloads of trees a day into wood chips and devour more wood in one month than an average size sawmill consumes in an entire year.

As of the present writing, 300 million tons of these hardwood chips are exported to the pulp and paper mills of Japan and Korea every year. Alarmingly, this is still a growing trend. Export of hardwood chips has increased 500 percent over a six-year period. Since these chip-mills, can use any size tree, including tops, providing wood for these industries will quickly deplete the land of quality hardwoods and have long term impacts on the overall health and bio-diversity of forests throughout the region. Ownership of forestland is gradually shifting from farmers to absentee landowners which further exacerbates the problem of alienation from the life and welfare of the land. Already, the overall cut is beginning to exceed forest growth.

Now and then we pass by a few fourteen foot Holly trees (Ilex Vomitoria). When I first noticed these prickly evergreens on previous ventures through Big South Fork, the females displaying red berries during season, they appeared somewhat out of place; apparently they're right at home. So I changed my mind. Now they look as natural to me as any oak. It has also been said that the Cherokee were turned on to this bush by other Indians. They apparently valued it enough to transplant a grove from the coastal plain up into the highlands. The natives call it yaupon. Traditionally, yaupon was the source of a concoction called the Black Drink. It is one of the few plants indigenous to North America that contains caffeine, which conveniently concentrates in the leaves when they are first growing in the spring. Not being ones to pass up such a stimulating buzz, the Cherokee collected the leaves and roasted them to increase the caffeine's solubility in hot water; sort of a native coffee or black tea. Caffeine is a also a diuretic; in the native belief structure, profuse sweating helps to remove physical and spiritual impurities from one's system. Only adult males could partake of the Black Drink, and they sipped it during morning gatherings while discussing the issues of the day. What? No creamer? Other uses of the black drink stemmed from its emetic properties, so it was also employed to effect extreme forms of purification before battles.

We paused momentarily at the arch, and being more interested in moving to generate some vital heat than in either geology or botany, we promptly continued along the trail until emerging from the wooded path, followed it up a muddy road for a mile or so onto gravel lanes, and into a trailhead clearing. We were soon breakfasting at Peter's Mountain, which is basically a parking lot with a few signs and fiberglass shitter in the middle of nowhere. Three local bow hunters pulled up in a truck, and quickly disappeared down into the woods in orange vests, while we cooked grits and removed extra clothing.

Upon resuming the hike, we got off trail almost immediately and walked

a few strong miles along a fine ridgetop dirt road straight over Lexton

Mountain before realizing that we were nowhere near the Trace. Instead

of doubling back, we committed to an alternate route and descended an eroded

horse trail where I lost the silver garuda off my mala in the tangle of

blackberry briars. Emerging into a sunny hollow near Bell Farm Horse Camp,

we ate lunch in the sun, sitting in an overgrown field along the banks

of Rock Creek. After fording, we trucked steadily eastward on the valley

road past a number of horse farms. The lane, an old railroadbed, was quiet

and fairly shady, never angling far from the creek. We walked four abreast

at a good pace for a few hours, paralleling the Trace which ran along the

ridgetop south of us. Late in the afternoon we removed boots to recross

Rock Creek before climbing a steep road that led up over the ridge we'd

been paralleling. According to the map, our path should have intersected

the Sheltowee Trace somewhere not too far up ahead on the north slope.

However, before getting to this point, the way became steep, the sky darkened

and we grew tired. We decided to make camp and find the junction in the

morning. Marc volunteered to scout for us and dropped off the steep edge

of the path to look down under the rhodedendrons near the little brook

at the bottom of the ravine. Plenty of privacy, a trickle of fresh water,

and enough room to pitch a few tents.

Thursday, November 15

Morning was cold and threatening rain again, so we broke camp early,

hoping to be back on the correct course before lunch.  We

climbed back up to the old road and soon came to the place where we thought

the Trace should have crossed, but there was nothing to indicate

any intersection of trails. In particular, we were looking for any trees

marked with the sign of a white turtle. There was

nothing to be seen.

We

climbed back up to the old road and soon came to the place where we thought

the Trace should have crossed, but there was nothing to indicate

any intersection of trails. In particular, we were looking for any trees

marked with the sign of a white turtle. There was

nothing to be seen.

I backtracked a little ways, checked the topographic map three or four times at an intriguing turn in the path that featured some rusty automotive garbage, but the Trace just wasn't to be found. We decided to walk to the ridgetop and see what we might discover up there. It began to rain lightly as we crested and soon came upon two logging trucks parked in the middle of the road; one was backed up perpendicular against the right side of the other in an attempt to keep the entire load of logs from falling off.

We said good morning to the drivers and asked if they knew anything

about the whereabouts of the Sheltowee Trace. They pointed to a house up

the road where they believed someone might know. It wasn't like we were

lost. I could point out where we were on the map; but the trail seemed

to be missing. In his old age, Boone was asked if he'd ever been lost.  He

wouldn't say he'd been lost , but admitted that he had once been bewildered

for three days. It began to sprinkle as we approached a small quarried

cabin with a smoking chimney. A shaggy vet kindly invited us in to stand

by the stove while we talked. The house had a concrete floor and the fellow

kept his heavy, worn army jacket and muddy boots on the whole time. Perhaps

he was only living there for hunting season, but beyond its sparse decor,

it actually looked like he may have occupied the place year-round. He said

that this area was called Bald Knob and that he'd heard something about

the Trace being nearby but had absolutely no idea where it was and basically

pointed us back down the hill. So we thanked him and headed back toward

the logging trucks while discussing the situation. Here we immediately

encountered a local preacher with a pickup who happened by and offered

to take us to a location where we could return to the trail. We happily

hopped in the back as the air got wetter and colder. The good man drove

us eight miles along the Laurel Ridge Road and back over Rock Creek to

the Yamacraw bridge.

He

wouldn't say he'd been lost , but admitted that he had once been bewildered

for three days. It began to sprinkle as we approached a small quarried

cabin with a smoking chimney. A shaggy vet kindly invited us in to stand

by the stove while we talked. The house had a concrete floor and the fellow

kept his heavy, worn army jacket and muddy boots on the whole time. Perhaps

he was only living there for hunting season, but beyond its sparse decor,

it actually looked like he may have occupied the place year-round. He said

that this area was called Bald Knob and that he'd heard something about

the Trace being nearby but had absolutely no idea where it was and basically

pointed us back down the hill. So we thanked him and headed back toward

the logging trucks while discussing the situation. Here we immediately

encountered a local preacher with a pickup who happened by and offered

to take us to a location where we could return to the trail. We happily

hopped in the back as the air got wetter and colder. The good man drove

us eight miles along the Laurel Ridge Road and back over Rock Creek to

the Yamacraw bridge.

There is a little store on this corner called Little South Fork where we sipped cocoa and called home to find out what may have happened to our compadres. The telephone had a big steel dial and getting through was not easy. They still have operators like Ernestine out this way. We sipped coffee and ate junk food, while we waited for a return call. The teenage girl behind the counter was talking to her mother in the back room, trying to convince her to buy a tanning bed for the store. I pondered this fascination with tanning beds. For most of the year, we get plenty of sun in the south. After we got our call through, we thanked her and headed east, where the trail crosses Big South Fork on a highway bridge, before turning north through the woods along the eastern bank.

The Cherokee Indians originally called Big South Fork the Flute River and in through here you can see why. The valley narrows and the river channel runs straight for long stretches. In places, BSF has carved almost 600 feet through the plateau as it works toward the Cumberland, although around here, it is around 400 feet from the cliffline. Rushing water has scoured away the soil from the steep banks so that old beds of bare rock are exposed high above water line. On later trips I was to learn that seeing this depends on how much water they are letting through the dam as well as how much it has been raining. Hundred year old tree trunks were strewn like litter on both sides of the channel, some twenty feet above the current water level.

We were now almost thirty miles from where we'd started. This fact combined with the raw weather, to give me the feeling that one way or another, we were really beginning to get out there. I observed the channel and thought about how much energy this groove carries and yet it is not even considered a major artery; otherwise they certainly would have already dammed it. In through here, Big South Fork feels very wild and young, powerful and free flowing. Natural energy moving unobstructedly through the organic channel systems of Turtle Island. Clear seeing of earth processes reflect individual and collective aspects of mind, allowing us to perceive an array of phenomena at new levels enabling our inner world to resonate and reflect the energy, power and absolute freedom of reality expressed in the particularities of natural expression, the terma buried in the perceptual jungle before us. Meditation on beauty naturally helps breach internal dams and experience free river siddhi of liberated awareness. In the middle of the afternoon, we broke on a big rock at River's edge and I bored everyone with stories from my childhood.

Supposedly, the first white men to see Big South Fork (1769) were longhunters led by Kasper Mansker and Nancy, his longrifle, not his wife. Scattered farms and stills (which increased the market value of corn) were established in the some of the fertile bottoms and coves during the 19th Century, before logging and mining interests gouged the area in the early part of the 20th. A few oil wells were dug. A few isolated hilltops were cleared. Life moved at another pace. You had to. There was no easy way in and out of these hollows. Yet some little minds never sleep. In the spirit of restless worker ants, the Army Corps of Engineers had actually proposed building a dam in a narrow part of the BSF gorge through southern Kentucky way back in 1933. The Devil's Jump Dam would have been 500 feet high, the tallest in the east; most of the trail we'd walked since Monday would have been under hundreds of feet of water. Construction was actually authorized by the questionable council of the US Congress several times throughout the 50's and 60's but was repeatedly turned down by the House of Representatives. Concerted efforts by a large coalition of Tennessee conservation groups led to the establishment of the Big South Fork National River and Recreation Area in 1976. Pshew. Thank you.

Afternoon brings more rain, dripping from our hoods and splattering

on leathery rhodedendron leaves, softening the trail. We cross Lick and

Negro, two pretty little creeks, on slippery footbridges, before arriving

at Alum Campground; an ugly little installation with tables, shitters painted

green, no running water and a boat ramp. We were the only folks that slept

there that night. They have those square gravel pads for tents that you

can never seem to penetrate with a tent stake. At least they are level.

Friday, November 16

1864: Atlanta is in flames. Every building except the churches and brothels is burnt to the ground. Sherman begins marching to the sea.Alum Ford is named for an alum mine located on the other side of the river which was a source of aluminum phosphate; I have no more information on the place. The day's plan had Gyatso and Jenny stay at the riverside campground. Marc and I would trek the eight miles to the rendezvous point without them to meet the next crew who were to arrive early in the afternoon. Skies were grey but no precipitation fell all morning. In spite of my advice, Gyatso had purchased cheap shoes and was having a difficult time walking any further. Here, I'll let her tell you:

1975: My oldest son Isaiah is born in an army tent on The Farm in Summertown

In here is where I have to do my shoe confession; my feet were killing me! I had huge bruises on my heels and blisters on my feet. It was my fault for being so cheap. Padma Shugchang had talked several times about getting the right foot wear. I don't like shoes much and always have a hard time getting them to fit right. In trying to save money, I kept buying shoes on sale. I could have had a really nice pair of hiking boots by now for all the wrong shoes I had bought. No blister kit was going to get me out of this one. I tried tightening my boots and loosening them. I walked until I couldn't walk anymore. Everyone had to slow down for me.

Well, there you have it. A road led from the campground out to the

town of Flat Rock; the vehicle we were meeting would be able to fetch the

ladies easily. We said goodbye and promised to return, setting out early

before it was obvious what kind of weather we were going to have today.

The trail wound along the east bank of the Cumberland and soon passed through

a very magical little section along Yahoo Creek, where we sat down. The

sun had penetrated the clouds and we got quiet enough to listen to the

early morning birds for awhile, to breathe easy and feel the day come on

before the main thrust. Huge Poplars, Sweetgums and Hemlocks thrust up

above waxy Rhodedendrons crowding the understory. Cliffs, boulders, a waterfall,

rock formations, flow together here in a mossy, sun shafted hollow. Enchanted

green space. An inviting trail leads back to Yahoo Falls. This was sacred

ground to the Indians, a traditional meeting place where generations of

great Cherokee orators would speak to their people about important issues.

Although the curtain of water is not very broad, Yahoo

Falls is the tallest waterfall in Kentucky, dropping 113 feet into

a small pool. Underneath and behind the falls is a massive rock shelter.

This was the scene of a terrible massacre on Friday, August 10th, 1810.

We decided to save an actual trip to the falls for the future and kept moving. The entire area around the rockhouse is an obvious power place and one of the most attractive spaces we have passed through so far. All that currently marks the tragedy is a small gravestone with Jake Troxell's name on it, located by the turnoff to the Falls where the front guard made their last stand.

The Trace follows along a three mile S - shaped curve in the Big South Fork before allowing one last look at the green water as the path climbs east. Crossing a bridge and gradually rising along Big Creek, then following a tributary to the head of the drainage, where a small waterfall spills over a semi-circular bluff in large and very dark rockhouse. We have now re-entered Daniel Boone National Forest. Formerly known as the Cumberland National Forest, it was renamed by LBJ in 1966 to commemorate the spirit of the man whose name has become legendary. The DBNF encompasses over 672,000 acres, much of which is characterized by steep forested ridges, narrow valleys, and over 3,400 miles of rocky cliffline.

We climb east to the top of the plateau, and are soon walking out of

the woods through someone's backyard, past private residences and crossing

Hwy. 27 into the desolate town of Flat Rock. The plan is for us to sit

here under the picnic shed at the Baptist Church and to wait for the arrival

of supplies and a new crew who will join us for phase 2. We make lunch,

read and reason for over three hours beyond the agreed upon time. Some

speculation about what may have happened. The usual last minute this and

that no doubt. They finally arrive late in the afternoon, and we immediately

direct them to pick up Gyatso and Jenny at Alum Ford. They soon return;

some ride and others of us walk a parrallel mile through the trees to a

trailhead parking area. Needless to say, Gyatso rode in the car. At the

trailhead we all donned packs and walked off into twilit woods, and by

dark we make camp about two miles from the car upon soft earth in a piney

grove on the Stearns Ranger District. It is good to welcome new folks onto

the trail. We stay up late talking and drinking tea; I naturally share

in their enthusiasm about being out here.

Saturday, November 17

My daughter Zoe (15), Tsering (22) and Samten (45) are with us now.

Many trains rolled through last night. The tracks run along side the highway

right through Stearns. Vowing next time to try and hike a little further

east into the hollow before throwing down the bedroll. On the up side,

we have been resupplied with cashew butter. Gyatso and Jenny stick their

thumbs and get picked up by a local woman who drives them all the way to

their car in Pickett State Park, Tennessee, after detouring to give them

a look at Cumberland Falls. But let her tell you:

My car was about 45 miles away. Jen wanted to stay with her friends, but didn't want her old mom hitching alone, so the next morning we said goodbye to the gang and started on our adventure. An old beat up car stopped to pick us up almost right away. A nice lady named Elizabeth was behind the wheel. She'd been in an argument with her teenage son and had gone to the tanning beds early. When we told her we'd been hiking and that our friends were heading to Cumberland Falls, she turned the car around and drove us there, insisiting, "We're so close and its too pretty to miss." So we got to enjoy the Falls for awhile, achey feet and all. When I told her where we needed to go, she balked and then said, "If I'm doing a good deed, my car can't break down. So let's go..." She took us all the way back to Pickett and we ended up talking for hours. She opened herself to us like we were family and told us she was battling cancer. It was getting dark when she finally left us. We had been with Elizabeth most of the day. Jen and I felt she was an angel. We still think of her with gratitude remembering the good feeling we shared.

We start moving east after morning's grits and tea, heading down

a shady path, working around boulders into a lush hollow along Railroad

Ford Creek. Although a little hard to believe, the Stearns Coal and Lumber

Company ran a train down here along a narrow floodplain in the 1930's to

service coal mines. Outside of an obvious mound of tailings and some orange

acid puddles melting across the path now and then, only a narrow and level

bed which supports the trail gives any indication that such activity ever

existed here. The Trace continues east along the lush, almost semi-tropical

vegetation of Barren Fork, most of the afternoon. We rise out of the gash

at the end of a good long day, cross 700 and bed down in the bare woods

of a small hollow high among the rolling ridges west of the Cumberland

River. Samten lost his wind-breaker near the end of the day, yet was still

fully capable of breaking wind, even without accessories. A spring of fresh

water under some brush in a low place supplies all our needs. We squeeze

the tents in among some fallen trees on the narrow bottom. The sky threatens

rain at day's end, but withholds. We are unexplainably happy to be together

out here under the grey skies. To be alive is a strange and wonderful thing.

Bless all of the people who still live up in these hills.

Sunday, November 18

Sunday morning is beautiful and sunny. The air is alive with a nice

breeze that took away last night's clouds. We move briskly along 700, waving

good morning to folks who are driving to church. Across high scenic ridges

through a rural neighborhood for a few miles before twisting down toward

the Cumberland on an unspecified dirt road marked Indian Garden Stables.

Of course we passed it and went an hour out of the way before finding our

way back to it. Apparently, the jaunt was sufficiently absorbing, at least

until we realized our error and turned around. Tsering and I got out front,

found the turn off the blacktop and rolled on down through the woods. We

have good rapport at times and I can feel her heart; I also have a good

relationship with her husband, Padma Ridgzin. Unfortunately it seems almost

impossible to be in good communication with both of them at the same time.

So it goes. After we found the trail we were bounding ahead, and as usual,

since there was still a possibility of taking a wrong turn and getting

lost before reaching the river, we tried to mark the way for our straggling

companions by leaving sticks in the shape of an arrow, but nevertheless,

a few managed not to notice this and took a little longer getting to the

river than they would have liked.

By noon, we were all sitting on a boulder on the banks of the Cumberland, burning sage and offering prayers. Even this far up towards the headwaters, this was no mere creek, but a powerful current . Originally named "Chauouanons" or Shawnee River, by Louis Jolliet in 1674, it rises in hundreds of shadowy coves and hollows in the Cumberland Mountains and twists westward across the plateau through rapids, falls and gorges. Slowed by four dams and winding down through the Nashville Basin, bowing intensely for most of its 680 miles, before merging with the Tennessee north of Land Between the Lakes in western Kentucky. The total area of the drainage basin covers over 18,000 square miles. It has been designated a wild river for the next twelve miles or so before it hits the massive Lake Cumberland; 63,000 acres of water backed up along 1255 miles of shoreline, floating the highest number of luxury houseboats of any lake in the US. It is the biggest manmade lake in the world if you are simply measuring shoreline. Still not interested? Me either. But I did hear that the park there has an abundance of raccoon. Lake Cumberland is backed up for 101 miles on the Cumberland River by Wolf Creek Dam, a 240 foot high embankment built in the early 1950,s. But that's all downstream from here. This far upstream, it still presents a very wide, roaring flow, breaking white on an outcropping of rocks toward the farside, moving swiftly west. We snacked here and moved along with good wind, breaking for lunch in a sunny field which had recently been used as a hunters camp. All in all, we walked over seven miles along the bank that afternoon.

It often happens that a pair of us will get out ahead of everyone for a stretch of trail. Over the course of a week or so, everyone naturally gets some time alone with everyone else. Even then, we may not speak about anything in particular, that is, nothing especially intimate or personal. There are times out here when we are available for each other without anyone else present and that in itself is as special and ordinary as it should be. Good to be non-conceptually together, just two or three of us at times, sharing some sutra,in the original sense of a meeting of minds, sharing in some part of essential reality. Due to the nature of the mindspace we occupy, there are too few ways for us to share this quality of time alone very often. Both within and without, there is an unspoken conspiracy against it and yet intimacy is the lifeblood of the community.

During a trip to the Smokies the previous winter, we arrived in east Tennessee late on Sunday afternoon. We wanted to do a stretch of the Appalachian Trail. Snow was falling, it was already getting dark. We had to check in with the rangers for a back country permit and would get out on the trail early in the morning. After an MSG-free dinner in a Chinese restaurant, we drove to a low budget motel on the outskirts of town and paid for a night. As we entered the upstairs room, Getso immediately started organizing us so everyone knew just exactly who would sleep where. I quipped, Thanks Mom. Slightly offended, she explained that she was just trying to be practical, still, Why would I want to sleep with your teenage son, when I could cuddle with Tsering?

Tsering and I had hit our stride and were probably a mile ahead of everyone

by day's end. We approached the Gatliff bridge, an old world style structure,

faced with native sandstone, design influenced by similar works spanning

the Rhine River. Before it was finished in 1954, a small ferry operated

here which would take three cars across at a time. When the river was in

flood stage, the ferry was inoperable and people crossed in a basket hanging

from a cable. A basket? They must have really wanted to get across.

But because entertainment is scarce in these parts, they probably made

a good living at it. Tsering and I climb up over the highway, misinterpret

a badly placed sign for the Trace and keep walking for almost another hour,

dragging our full packs up to a high overlook on the west bank of the falls

before realizing this was a mistake. We had to go back down and cross the

bridge to the eastern bank of the river.  By

the time we got down, everyone else was arriving at the bridge and we all

walked over into the park together, where as previously arranged, we met

Padma Yiga and friends. Yiga was sitting in the sun on a patch of very

green grass under a tree by the riverside, like a yogi by the Ganges. He

had been at the Vajrapani initiation last week at Padma Gochen Ling and

promised he'd be back with some of his friends from Minnesota to join us

on the Trace. We embraced and he introduced me to his northron amigos,

both of whom are named David.

By

the time we got down, everyone else was arriving at the bridge and we all

walked over into the park together, where as previously arranged, we met

Padma Yiga and friends. Yiga was sitting in the sun on a patch of very

green grass under a tree by the riverside, like a yogi by the Ganges. He

had been at the Vajrapani initiation last week at Padma Gochen Ling and

promised he'd be back with some of his friends from Minnesota to join us

on the Trace. We embraced and he introduced me to his northron amigos,

both of whom are named David.

The older David, of Scandanavian stock, owned a big house in Minneapolis

where both Yiga and the younger David were renting. With long blonde hair,

the bigger of the two was a confident bloke in his early thirties. He announced

his intention to fast for a few days, which I found a bit strange considering

the energy required to keep moving along the path with a full pack. Younger

David is of Jewish ancestry, smaller than his elder, and wore a brown ponytail.

This little guy had recently become a father although for some reason,

he was not yet living with the mom. We found a space in a picnic area around

the park pool which was closed for the season, where our lanterns attracted

the attention of the local park policeman. After he made closure with us

about leaving it exactly as we found it, we were allowed to spend

the night there. Padma Yiga and Tsering were the natural choice for the

motorized run down to Flat Rock to retrieve her car, so she could in turn

help him park his rig a few days north up the trail. They returned late

and had hassled about something; (maybe I'll find out what it was and

include a special feature on it in a future edition). The sky was clear

and the weather was getting delightfully cold. Saturn in Aquarius. We stayed

up eating and talking. Tsering said goodbye to us and left to return home

the following morning.

Monday, November 19

1863: Lincoln delivers the Gettysburg AddressThe first expedition through Cumberland Gap in 1750 by Dr. Thomas Walker, an early explorer, physician and surveyor. Walker named the Cumberland River after the 'fat and florid' William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland (1721-1765), son of Britain's George II. Billy was nicknamed The Butcher for his lack of compassion evidenced in brutal reprisals against the Scottish wounded following the Battle of Culloden Moor, an unsuccessful attempt to overthrow Billy's dad. In a real sense, Bloody Butch was probably responsible for a lot of the Scotch emigration to this part of the world.

1969: men walk on moon (second trip, Apollo 12)

1975: Padma Dechen is born in Pulaski Tennessee

Since 1650, the Cumberland had appeared on maps as the "Chauouanons" or Shawnee River, so what in hell was Doctor Tom thinking? Walker had been hired by a group of real estate speculators called the Loyal Land Co. of Virginia to check out southeastern Kentucky and in naming the river after the son of the British King, he was insuring both himself and his employers the favor of royal recognition and hopefully, perennial gratitude. He'd already met the Duke in person, and while apparently not in favor of Scottish independence, who knows what Walker really thought... The best tale I've heard to account for the renaming of the river involves a transplanted highlander who settled in the area and finally got an eye on the Cumberland River Valley from a height. Gazing into the distance he supposedly "Aye, well named it is, as crooked as the Duke himself. Walker's report on Kentucky was generally unfavorable: rugged terrain with little bottom land, strewn with thickly tangled woods. He went as far as the Rockcastle Hills and turned back. The company lost interest. Much of this area has since become included in the DBNF.

If LBJ can change the Cumberland National Forest to the Daniel Boone National Forest, doesn't this set a precedent? I would suggest that everything named Cumberland be changed to something more inspiring. Cumberland sounds burdenous. To encumber, hinder, weigh down, impede or hamper a function... From the Old French combre (14th c.) meaning, a dam or weir.... If this suggestion to change the name rubs traditionalists the wrong way, perhaps a compromise could be worked out; how about Cumberbund? That has a certain ring to it, no? In the interests of not totally upsetting the apple cart, this suggestion has two positive features, insofar as it eliminates any reference to the bloody Duke and - here's the clincher - most folks will never know the difference.

There has been a resort near the falls since 1875. In the early days, most of the clientel consisted of fisherman; fishermen, who, like many modern anglers, really needed a shower. It must've been quite cheap back then, because the only running water available was to stand under the falls themselves. The construction of a diversion dam for power was proposed in 1924 but was soon shot down, somewhat ironically, by those who wanted to use the river to move logs downstream. The Dupont family bought the falls for the state in 1930 and it became a state park in 1931.

Monday

seemed like the hardest stretch of the whole trip. Was this simply because

it was Monday? The day on which slavery began according to Black

Uhuru, who might know something about it. No, this time, it just happened

to be Monday. As often happens during personell transitions on the trail,

we stayed up too late last night talking and eating and didn't get moving

till almost noon. Then of course we had to stop, remove packs and crawl

over the fence to get out on the rock and look over the edge of the thundering

falls. The entire green river drops over sixty-eight foot Cumberland Falls,

and a fine spray rises and blows about from the plunge pool. This is declared

to be one of two places on earth which hosts a rainbow during the night

of a full moon. The other famous location is at Victoria Falls on the Zambezi

River in Africa. Or so they say. Even during the daytime the spray reveals

the pink and greens of rainbows in the sunlight. Actually, there are a

few other places where this phenomena can be observed, such as Lower Yosemite

Falls during spring snowmelt. And there are very likely others that nobody

is publicizing. No doubt. If you knew of another one, would you tell anybody?

Even now the sound is deafening, but at high water, the falls are

125 feet wide; at flood stage, the river expands to 300 feet, covering

the entire width of the exposed bedrock between the hills. The falls occur

about about thirty miles from the headwaters and offer a dramatic display

of sheer power, unlike the silence and subtlety of many other natural attractions

across the plateau. Almost seven hundred miles downstream, after being

detained by four dams, the river merges with the Tennessee, northwest of

Land Between the Lakes. The Cumberland's natural outlet into the Ohio is

restricted by another dam.

Monday

seemed like the hardest stretch of the whole trip. Was this simply because

it was Monday? The day on which slavery began according to Black

Uhuru, who might know something about it. No, this time, it just happened

to be Monday. As often happens during personell transitions on the trail,

we stayed up too late last night talking and eating and didn't get moving

till almost noon. Then of course we had to stop, remove packs and crawl

over the fence to get out on the rock and look over the edge of the thundering

falls. The entire green river drops over sixty-eight foot Cumberland Falls,

and a fine spray rises and blows about from the plunge pool. This is declared

to be one of two places on earth which hosts a rainbow during the night

of a full moon. The other famous location is at Victoria Falls on the Zambezi

River in Africa. Or so they say. Even during the daytime the spray reveals

the pink and greens of rainbows in the sunlight. Actually, there are a

few other places where this phenomena can be observed, such as Lower Yosemite

Falls during spring snowmelt. And there are very likely others that nobody

is publicizing. No doubt. If you knew of another one, would you tell anybody?

Even now the sound is deafening, but at high water, the falls are

125 feet wide; at flood stage, the river expands to 300 feet, covering

the entire width of the exposed bedrock between the hills. The falls occur

about about thirty miles from the headwaters and offer a dramatic display

of sheer power, unlike the silence and subtlety of many other natural attractions

across the plateau. Almost seven hundred miles downstream, after being

detained by four dams, the river merges with the Tennessee, northwest of

Land Between the Lakes. The Cumberland's natural outlet into the Ohio is

restricted by another dam.

This section of the Trace is called the Moonbow trail. Crossing Dog

Slaughter Creek was one of the more memorable events of the day. A small

waterfall is only a little way upstream and the ford was relatively simple

but the name seems to express something of the day's difficulties. Trudging

along the east bank of the Cumberland, the floodplain is narrow and the

path is continually rising and immediately coming down across dozens of

twenty to thirty foot high hills. These were created by landslides as the

river undercut its banks and debris settled as a slope that runs down to

the present river's edge. Shlump. Spent the night at the Star Creek

shelter, which sounds much fancier than it really is. There is a primitive

camp there, a mere five miles downstream from Cumberland Falls. No heroes

today. Everyone is exhausted and more than ready to stop. Yiga's friends

are still checking me out, and although we have not spoken much, the exertion

has given us a common bond and the energy begins to loosen up.

Tuesday November 20

Thus situated, many hundred of miles from our families in the howling wilderness, I believe few would have equally enjoyed the happiness we experienced. I often observed to my brother, You see now how little nature requires to be satisfied. Felicity, the companion of content, is rather found in our own breasts than in the enjoyment of external things; and I firmly believe it requires but a little philosophy to make a man happy in whatever state he is. This consists in a full resignation to the will of Providence; and a resigned soul finds pleasure in a path strewned with briars and thorns.Sunny and clear, a brilliant autumn day. This is ideal backpacking weather. Everyone of us feels fortunate to be here. We strap in to begin after the obligatory grits and tea, continue along the Cumberland. Today is a yes. We are far more energized, feeling good. The weight of the pack on shoulders and hips is a form of power, quite comfortable, sweating not fifteen minutes into the trail, morning's chill cooling forehead in the early shadows, taking it all in, invoking the mandala. Colors are much brighter, heart throbs with warm blood, diaphragm expands and draws fresh oxygen into the mix. The arbitrary view through the woods toward the white streak of some waterfall or the ancient, lichen-dappled grey and velvet green of moss-softened rock outcroppings resolves clearer, and looking further seems suddenly more compelling in the morning sun. At one point, while descending through a very bushy section of trail, both Samten and I, in separate incidents, tripped over a rock or a root and then went flying at speed, head first toward the fresh stump of a large tree. As my body rushed forward, the intertia of the pack was quickly driving me down toward impact and just when my head was about to make contact with the heartwood, the upper frame of the pack, slammed into the stump and stopped me, my skull only inches from a terrific headache. Same exact thing happened to Samten. Alright, alright. The force of the collision bent the frame on both of our packs. Laughter. Luck.-Daniel Boone

Even so, the trail is kinder today and we break early to camp on a wide

sandy beach where Laurel Creek drains into the Cumberland which has already

become currentless backwater behind the dam. This is called Mouth of Laurel

and the last we will see of the Cumberland as we continue to move toward

higher ground toward the northeast. David the elder begins to open and

in praising the utility of a good head wrap, tells tales of his travels

in Rajasthan and the petty jealousies he observed in the process of distributing

a few cheap gifts to those who had befriended him. Meditating the mind

of man and again stories of India when I suddenly recall the Khenpo's recent

invitation to attend the consecration of their new temple in Sarnath. For

the first time, I begin to consider what a rare opportunity this is and

feel into the possiblity of actually going.

Wednesday November 21

We have arrived in plenty of time to meet the resupply run coming up

tomorrow from the gar. Most of the day is spent laying in the sun, talking

on the beach where we'd camped the previous night. Consideration of the

triality indicated in the Yogacara tradition, which conceptually divides

truth or reality three ways;

1) the impure relative truth which is basically imaginary and false. Seeing the moon in the waterThis elaboration came about to counter a wrong understanding of the two truths, leading to the notion that there was only a negative sunyata or an endless maya, which is practically nihilism and cannot appreciate the possibility of skilfull means and the blessings of Padmasambhava. Through the converse, Yiga gets a bit jangley and I address this while the two Davids observe how it goes. After lunch we pack up and follow Laurel Creek upstream into a pleasant woody basin below a dam which holds back what has become Laurel River Lake. Crossing the dam and walking through the park, Marc and I encounter only one elderly employee with a leaf blower in a picnic area. Like all things, the place is completely empty. We do not yet realize that it is also closed for the season. The old man knew this as well as what we were about, and so apparently had no desire to bother us with technicalities. Arriving at Holly Bay Campground we set up near the end of one of the peninsulas that finger out into the lake. Nice picnic tables. A sign reads section D-4 and after a moment's repose, this is interpreted as a celebration of time, the element of wind or motion animating our 3D world, an invocation of the fourth dimension, reminding us of what it is which allows us to perceive one another. Morale is good. We are all glad to be sitting here in the last light of day, simply playing with words. We can do without intellectual stimulation for the moment.

2) the pure relative truth which corresponds to the actuality of interdependence. Seeing the moon,s reflection in the water

3) the non-conceptual absolute truth. The moon itself, beyond perception

Thursday November 22, 1995

1864: Hood's Army of the Tennessee, marching north from Florence, makes first contact with the Federals cavalry on Jackson's Military Road in Lawrenceburg. After a few hours of heavy fighting, Ross pulls his men back to Pulaski.Cold, wet morning. Zoe and I walk into Baldrock, a simple country store set in a grassy lot amidst a few other wooden buildings, a mile or so from camp. On the way out, I realize the park is officially closed and we will not be able to drive back in to the campsite. Today, as previously arranged, we meet Padma Tenkar, Rigdzin and Jenny, who have driven all the way up from Turtle Hill. We link up right on time at an isolated country store without incident and drive back to park at the gated entrance on Holly Bay. I say 'without incident' because knowing these people, a lack of anything happening, even during a ten minute ride, is worth mentioning. The boys help walk in a few coolers and such. After hugs and hellos, Tenkar and I drive a winding road into Corbin to do everyone's laundry, then shopped to buy more nylon socks to replace the ones which had melted in the dryer. I am amazed at how much of the town is open for business on a national holiday, but then again, these establishments are akin to temples where the real religion of our republic is practiced. Wally World probably services far more people than attend churches, even on Sundays, even out here in the Bible Belt. Rain falls heavier afternoon.

1955: Ginsberg,s first reading of Howl at the Six Gallery in SF

1963: JFK assassinated in Dealey Plaza, Dallas

1963: Aldous Huxley died of cancer on LSD in California.

When we return, a system of tarps has been set up as a roof over two

picnic tables joined end to end, all the candle lanterns are lit and incense

burns among the sumptuous spread on the table below. The Coleman is fired

up, we offer herbs and prayers before sharing in a feast of rice and pineapple

gluten, tukpa (Tibetan noodle soup), kale, cranberry sauce, hot chocolate

soymilk, pistachio baclava... the works. Far from the haunts of men, we

huddled amidst the silent oaks on the edge of a desolate lake in the hills

of southern Kentucky, the world wrapped in a cold grey mist, at times precipitating

a fine, icy drizzle; the sound of frozen rain pelting dead leaves throughout

the bare woods. Relatively exposed to the elements, our normally insular

existence stripped down to some very basic gear, raw weather driving us

into gloves, hats and a deeper appreciation for every bit of it, stoking

the fires in the heart. We commune in grateful acceptance for our life

here. Best Thanksgiving Dinner ever.

Friday November 23

Tenkar drove off with Zoe as we broke camp. Jenny (14), who hitched back to Pickett with her mother last weekend, has returned for the remainder of the trip. She is the only girl with us now. Her father Ben, was one of the first people I met when I originally visited The Farm as a teenager. We were seated in a dark canvas tent on a wooden platform, eating breakfast on a sunny morning in February, 1974. This was part of the community kitchen. We occupied an old church pew located near a big rusty woodstove. Ben greeted me before I sat down beside him. We exchanged a few words, both of us eating a bowl of boiled soybeans flavored with a slab of margarine. We were listening in on a conversation these guys were having around the stove. One of the fellows, a chubby middle-aged visitor, mentioned that he could earn $50,000 a year laying carpet for a living. As if to balance things out, Ben leaned over to me and quipped, "How moral is it to earn that much money?" I didn't quite understand this at the time other than tune into the fact that morals were being assessed . Twenty years later, this shoot from the hip style judgement would be aimed at me. In 1989, Padma Gyatso, took Buddhist refuge vows and began a daily practice. She and Ben gradually separated and in 1993, Ben went to a lawyer, a fellow named McNutt who ironically, was also a student of the Khenpos at the time. Ben got McNutt to draw up some kind of legal document to the effect that I had better stay away from Jenny, his youngest daughter, who at the time, was good friends with my own daughter, Zoe. Apparently things were not going well for him and I was the scapegoat.

Dondrub was living in Vermont and in the midst of (what has since become a series) a reactive episode at the time. Upon Ben's request, Dondrub composed a letter which was to help in securing a legal deposition with suggestions of lurid tales and hippy degeneracy. Now two years later, none of this was an issue. I was basically the adult responsible for Jenny all the way out here in the lonely backwoods of Kentucky. My oh my. Go figure. When I first heard McNutt was paid to draw something up, I called him on the phone and said , "Hey Vajra Brother, what gives? Any reason you couldn't speak with me first before taking this one on?" McNutt replied that he was bound by his professional code not to talk to me as he was on a retainer.

At the following retreat, the Turtle Hill Sangha had an audience with the Khenpos in the main hall at Padma Gochen Ling in Monterey, where I explained what was happening. Khenpo Tsewang commented, "Oh, that's obnoxious... we are sorry to hear that..." When I mentioned that McNutt had taken on the case, they expressed some dismay and said, "Oh really?" At that point, there occured one of those strange moments where nobody can quite believe what is happening; McNutt just happened to walk across the open double door entrance of the temple, and looked in. Suddenly, we all turned and along with the Khenpos, silently acknowledged McNutt as he gradually realized what was transpiring. He only had one move left and I will say that I had to admire his effort at this point; he forced a smile and a wave, the veins in his central forehead bulging like battery cables which narrowed and merged into a V between his eyebrows. McNutt has since become an Episcopalian Minister.

The path loops around the edge of the lake and heads overland from the

northwestern edge of the reserve. We sweat our way up a rise where we stop

to rest on a large log. In demonstrating what not to do, I lean back and

the weight of the pack takes over; the bigger David caught me by the hand

before I fell backwards. Are we buds yet or what? Cross a road and

descend through a lush groove created by Powder Creek into a beautiful

little area know as the Cane Creek Wildlife Management Area. At the shady

bottom, lush growth and a good footbridge. We sleep on the banks of the

Big Dog and ponder on the more absurd possibilities for the origin of such

a name.

Saturday November 24

Today we cross the Little Dog, swing on the suspension bridge over Sinking Creek, and near day's end, pass through 300 acres of reclaimed strip mine. I sit on the edge of the woods, waiting for everyone while gazing at the afternoon light illuminate the grassy slopes of these truncated pyramids. We are skirting the edge of the eastern coal fields, that Kentucky portion of the Cumberland Plateau (about 11,180 square miles) which consists of networks of narrow, winding valleys cutting through tens of millions of years carboniferous sediments. Thousands of little tributaries drain into five major arteries, the Licking, Big and Little Sandy, the Cumberland and the Kentucky. All originate in this general region. The majority of level land occurs in narrow river and creek valleys of widths varying from a few yards to hardly more than a mile. This is the interior uplands of Appalachia, where coal and lumber trucks dominate the roads and poverty is a legacy.

Eventually, everyone catches up. We burn Tibetan and watch the sinking

sun turn the tall grass golden. Sitting in silence at the end of another

beautiful day, sharing water. Soon, with a hand to get up, I leave this

barren oasis of reclamation, heading back into the woods, quickly fording

the south fork of the Pine, and making camp before dark in a moist hollow

on Poison Honey Fork. As planned, it was time for PadmaYiga and the two

David's to split and before the sun was down. Hugs and goodbyes before

they headed up and out of the valley to retrieve their car, which was parked

six days previous, in a small neighborhood less than a mile from where

we camped.. The last we heard from them was a final shout of Lha-Gyal-Lo

! ('victory to the gods'; in imitation of how KPSR likes to end our

ritual gatherings) from the top of the ravine.

Sunday November 25

Hopped the guardrails and crossed Hwy. 80 in the early morning light, supported by a good ascending vital energy. Soon we reached Hawk Creek. Today is one of those days that inherently feels like a Sunday. Since there is nothing cosmic about such a notion, I must simply be a reading a vibrational quality based in a widely accepted tradition. I never mind forgetting what day it is; so much the better. But everybody knows today is Sunday. At this point the crew consists of myself, Samten, Marc, Rigdzin and Jenny. The banks of Hawk Creek are beautiful and still sport a few unidentified wildflowers, even this late in the year. We cross the suspension bridge and eat lunch on the sunny north bank before moving along the edge of a lush basin of healthy rhodedendron, waterfalls and some tasty exposures of sandstone. Considering that it is already such a nice place in late November, this little sanctuary must be very inspiring in full summer bloom. The path through here is signed on trees either in the form of a white turtle or a white diamond. This latter image repeatedly brought to mind the phrase, footsteps on the diamond path,, which may be considered on its own merits but is derived from the title of a very valuable collection of teachings by Tarthang Tulku, a copy of which can be found in any dwelling associated with Turtle Hill.

In response to inadvertent prodding, we adopted the practice of repeating a short Tibetan prayer every time we would see one of the diamonds. For the most part we used only one prayer. It is taken from a string of thirteen dedication prayers which we chant at the end of practice. It falls ninth in the sequence;

ten pe pal jur la me zhab pe ten

ten dzin chu bu sa teng yong la chab

ten pe jin dag nga tang jor pa je

ten pa yun ring ne pe ta shi shog

Marc, who had been doing most of his practice in English for awhile, was able to provide us with a good translation-

May the lotus feet of the guru who glorifies the teachings be firm

May the noble ones who hold the teachings encompass the earth

May the prosperity and dominion of the patrons of the teachings increase

May the teachings auspiciously remain for a long time.

We begin to notice the presence of what look like mountain bike

tire tracks on the path and wonder what kind of super athlete would be

able to pump these slopes. We ascend out of the ravine into a rural area,

encountering something not seen before on the trail; human beings coming

from the other way. But these were alien types, sheathed in PVC and riding

machines. We had to move aside. Dirt bikers, heading down in to an area

where they should not have been. Dad and his boy were completely covered

in white plastic body armor. They slowed down and shut their engines off

when we met, removed their helmets and spoke with us real friendly for

a minute before buzzing on. Aye, the politics of outlaws. We had no idea

that we were about to enter almost six miles of ATV hell.

A chubby older woman in an army jacket rolls over the rise, whips round a sandy corner on a little mud-splattered, snarling dog of a four-wheeler and seeing our packs and no machines between our knees, slows down to talk:

Hey, where y,all headed?With that, she revs up the gas, does a little wheely and yells, "Hell, that's too much work! Git yerselves some wheels and have some fun!" before quickly disappearing down the muddy track, off into the woody distance.

Red River Gorge,

That's a long way from here. Those packs look heavy. You should git yerselves a couple of these!

Oh yeah?

Yeah!

All kinds of dirt bikes and ATV's are buzzing through these woods, coming through from all angles and directions, throttle open. Mindfulness is clearly a matter of survival now. Fathers on big hondas with their young sons on amazingly tiny machines, young boys zipping by in full plastic armor, as many simply in jeans with or without helmets, hair flying, girlfriend holding on behind as the bike skips across sandy hills like a Mexican space shuttle. Parts of the trail here are gouged six foot deep and equally wide through small hills. On hearing the approach of a motor, one must stop and lean against the muddy wall as swarms of growling bikes fly by, often less than a foot away.

Well, this is certainly Sunday. Having experienced American culture for forty years, there is understandably a palpable mania, well-evinced by these kids, most of them in their teens and twenties, a few up in their forties no doubt, to cram in as much action and wild riding as possible before loading up and heading home for another week of school or work. It must be great fun to ride out here on these sandy ridges and feel relatively liberating. On the other hand, they are endangering our lives, tearing up the flora, scaring off the fauna and make it kind of hard to simply relax and enjoy the walk. ATV's are restricted or forbidden on public lands in a number of states and are completely banned in the forests of Japan, the principal ATV manufacturing nation. Lately they are being used by Park Rangers with dope dogs to intimidate hikers in the far flung corners of various parks, such as Savage Gulf in Tennessee. I ain't saying ban them. Just don't allow them on the same trails that people with large packs are going to be walking on. This is the Sheltowee Trace and there is no alternative trail through this section.

Finally crossed I-75 around dusk and slept in Hazel Patch that night. We found a tiny corner of National Forest that poked into town between a church parking lot and a small residential area. There was only enough room for the five of us to lay down our bags on a ground cloth, but it was home enough for the night. The nearby Louisville, Nashville and Kentucky Railroad would come through now and again and wake us for a moment. But it was not often and the night passed well. A spur of the same line passes through the woods a few miles from Turtle Hill, 200 miles to the southwest of where we lay. You can usually hear it in the distance in the early evenings.

The L & N Railroad first came to Summertown in 1883. That is when all the clearcutting must have begun in earnest. Up until that point, there was a natural limit to how many trees would be harvested. A man armed with only an axe and a mule trying to clear land for his own fuel, fields and building needs was never much of a threat. The widespread destruction of the original forest did not really come until logging roads spread out from the railways up every hill and hollow, encouraging the removal of millions of grandfather hardwoods from previously untouched areas. It changed the whole economy of the region. In places that did not have a nearby river access, there was no other way than the railroad to get products to the greater market. Throughout the Cumberland Plateau and Highland Rim, where no coal was discovered, trees converted into lumber products were the primary resource destined for rail shipment.

In 1874, Killebrew wrote of the plains of Lawrence County: "In some cases, not a stick has ever been removed for several square miles. The wild deer sleeps as quietly as in the swamps of Arkansas. These flat lands are densely covered with white oak, post oak, chestnut, chestnut oak, black oak, red oak, and black jack timber.

"Hilly, broken land" were the words written on a 1797 map by Bradley to describe the 4000 square mile section south of the Duck and north of the Tennessee, where the Buffalo River actually flows. Turtle Hill lies a few miles northwest of the headwaters of the Buffalo. If the plains the Amish farm today were untouched in 1874, the hilly, broken land, around Summertown was very likely full of virgin stands for another decade or so, until the railroad made the timber industry possible. Many of these trees were harvested to make railroad ties. Subsequently, the old growth on the plateau and Highland Rim was regularly harvested and turned into barrel staves, hoops, siding, molding, dyewood, railroad car stock, blanks for shuttles, cordwood and other unfinished lumber products, all loaded on to trains at many small stations throughout the woods. Without concern for the future, the timber industry soon cut themselves right out of business.

By the turn of the century, the western escarpment of the plateau from eastern Kentucky to middle Tennessee was almost played out. White-tailed deer and bear were already extinct in eastern Kentucky and had to be reintroduced. And during the Depression, men were paid a dollar a day to tear up spur lines that were less than fifty years old. Good work if you could get it. More track got ripped up during the Depression than got put down in the first place.

We fell asleep to the sound of parishoners singing hymns in the little white chapel. Woke up a few times because we fell out so early. Up through the bare branches, the great square of Pegasus circled the zenith point. The night was clear enough that you could point out the glow of the Andromeda Galaxy, over two million light years away. The winged horse also brought up other thoughts.

A little more than a month previous, astronomers had found the second solar system beyond our own. 51 Pegasi, some 42 light years away, featuring a Juptier-sized planet orbiting a Sun-sized star about every 4 days. Looking up from the surface, the star would appear 30 times bigger than our Sun. It is either a gas giant which moved to this tight position from an orbit farther out, or a supermassive terrestrial planet. If this planet is really terrestrial, its surface would be covered by oceans of liquid aluminum, surrounded by an atmosphere of hot rock vapor. Eighteen more of these "epistellar jovian planets" have been discovered since then, suggesting that they are quite normal.