-

"Equality as a Cooperative Colony"

By: Charles L. Easton

"The Seattle Times"

Sunday, November 25, 1962

~ A Backward Look At a Utopina Plan ~

The utiopians hoped to convert the skeptical to their brand of socialism by example. To that end, they established hundreds of cooperative communities throughout the United States. Repeated failures, over several decades,gradually dulled the enthusiasm of all but the most faithful. By 1890, most radicals had turned to political action as the road to socialism.

But a few diehard cooperatives made a last stand in the Pacific Northwest. By the late 1890's, the Socialist Party, a loose, faction-ridden body at best, was splitting apart. The remaining believers in cooperation considered that the time had come to form their own organization.

In 1897, they met and formed The Brotherhood of the Cooperative Commonwealth.

-

"We declare it our purpose," said the constitution, "to readjust

measures and systems to the changed conditions of social and

industrial life that will break the power of monopoly and give the

people industiral as well as political freedom, and we organize with

the one definite aim in view - the establishment of the cooperative

commonwealth."

The declaration went on to say:

"The objects of the Brotherhood shall be:

1) To educate the people in the principles of socialism

2) To unite all socialists in one fraternal association

3) To establish cooperative colonies and industries, and so far as possible, concentrate those colonies and industries in one state until said state is socialized."

While most radical leaders dismissed the colonizing scheme of the brotherhood as utter nonsense, several leading socialists signed the charter, notabley Eugene V. Debs and Henry Demarest Lloyd.

A slate of officers was elected and the plans of the brotherhood widely advertised in Socialist and Populist publications throughout the country. Many Socialists assessed themselves 10 cents a month for the brotherhood's treasuury. In a short time, $10,000 had been raised. This sum, together with a membership fee of $160 from each colony family, insured adequate financial backing for the first venture.

Western Washington was chosen as the site of the first colony. Land was cheap and fertile and the climate was mild. Most important of all, Washington had just elected a Populist governor. It seemed the time was ripe for socialism.

The colony took its name from the title of one of Edward Bellamy's books, "Equality." Bellamy also was the author of the famous utopian tract, "Looking Backward."

Ed PeltonG.E. "Ed" Pelton, leader of the first group arriving late in 1897, bought 280 acres of land near Edison in Skagit County for $2,854.16. During the life of the colony more land was bought, bringing the total to nearly 500 acres. Pelton directed the members in clearing land, putting up a saw mill, and turning logs into usable lumber for building. His direction was efficient, for in a few months the colony was a going concern.

At its height, Equality boasted an extensive list of buildings:

Store Room

Printing Office

Two large Apartments

Barn

Root House

Bakery

Saw Mill

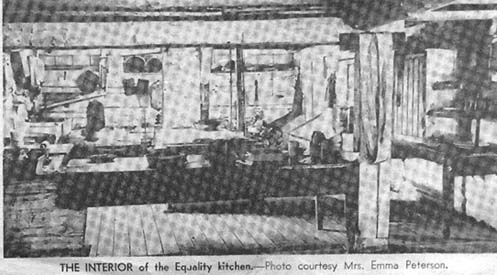

Dining Room and Kitchen

Milk House

Cereal and Coffee Factory

Copper Shop

Blacksmith Shop

Public Hall

Apiary

School HouseTheir publication, Industrial Freedom, reported the activities and progress of the colony. It seems to have had, for a time, a national circulation of several thousand. A young boy named Harry Ault got his start in journalism working for this publication. In later years he became editor of the Seattle Union Record.

Industrial Freedom evidently oversold the settlement; a group from Ohio, lured west by the paper, took one look at the melancholy stump-strewn landscape and left the same day for Bellingham Bay.

The colonist lived in true communal style in apartment buildings, though in time families were allowed to build separate dwellings. Each member was allowed to choose his own occupation, but had to be ready and willing to do any special jobs assigned to him by a proper official.

The work day normally was eight hours and all wages were equal. The work day for women was six hours but they received the same wage as men.

A town meeting was held weekly and all colonists of both sexes over 18 had a vote in deciding policy. Payment was in script. During the heyday of the colony the commissary was well stocked with quality goods at modest prices.

To this day, some Skagit Valley residents remember parents shaking their heads over "those crazy Socialists." Yet the colonists seem to have gotten along with their neighbors well enough. Some of the colony men had employment outside. Outsiders often attended the weekly colony dances.

For some time, possibly four years, the colony prospered. The land was fertile, the workers efficient and the leadership skilled and respected. But there is a serpent in every Eden and Equality professed to be an Eden of sorts.

The first colonists, especially the family men, were firmly convinced Socialists. Yet, even they did not always agree. More and more often, they questioned the official leadership.

Tempers flared and hard feelings developed among the "cooperators." The weekly meetings became prolonged wrangles. Eventually, the dispute became one continuous wrangle with meetings every night in the week.

A definite split appeared in the hardcore Socialist group. One faction held fast to the cooperative principle of subordination to the group. The other faction was infected with anarchist ideas and became increasingly restive under colony regulation.

This ideological dispute alone probably was enought to have destroyed the colony. But there were other problems. The colony was being helped to financial ruin by pseudosocialist free-loaders. Newcomers, professing socialism, arrived penniless agreeing to work out their $160 membership fee.

The unmarried men, especially, found the well stocked commissary and the home-cooked food most agreeable. They would work for a few weeks, draw on the commissary up to the limit, then sneak away to greener pastures. A few sharp operators seem to have gotten their fingers on some of the colony money before being thrown out.

During the first stages of the break-up, attempts were made to appease various factions. The records show that two groups within the colony, the Hertzka Colony and the Freeland Colony, were granted some kind of quasi-independence.

But by 1905, the colony was close to final dissolution. The land was mortgaged and taxes were delinquent. Some of the more affluent colonists had purchased tax certificates and were attempting to obtain deeds to the land they were holding. The final blow fell Februay 6, 1906.

In traditional anarchist style "a person or persons unknown" set fire to several buildings in the dead of night. The greatest loss was the gigantic barn which burned to the ground killing most of the colony cattle. The arsonists never were identified.

Within a month, a group of colonists petitioned the Superior Court in Mount Vernon to appoint a receiver for the property of the brotherhood. In their affidavit, they certified:

- "That during the

year 1905 there came into said association a class of so-called

socialists. . . . that there is a reign of terror existing in said

association, and that the lives of the members are in great danger....

that certain evil practices have existed so inculcated on the part

of some of the membrs of the association to such an extent as to

entirely thwart the purposes and objects of said association."

E.W. Ferris was appointed receiver. He sold the land to the highest cash bidder on the steps of the Skagit County Courthouse June 1, 1907, for $12,500 John J. Peth, the purchaser, was promptly challenged by a group of diehard cooperators who questioned the validity of the sale. The Superior Court, after many delays, found for Peth. On appeal, the State Supreme Court upheld the decision of the lower court.

Thus, finally, died Equality Colony. The founders all are dead and their surviving children are scattered. Equality has disappeared, leaving almost no trace in written history. But to a handful of survivors it must still be a vivid memory.

Mrs. Emma Peterson, daughter of a founder, Charles Herz, was born at the colony during its best days. She still owns and uses a cottage on former colony land as a week-end retreat. Though living and working in Seattle, she feels that this still is her home.

Today, a few buildings, a few old fruit trees and a tiny graveyard on a Skagit County hillside are all that remain of this endeavor to convert America to socialism."

Back to Equality Colony

Back to Equality Colony

Irish Family Tree

It is only with the heart that one can see rightly;

What is essential is invisible to the eye.

-- Antoine de Saint-Exupéry,

The Little Prince

As you stroll down memory lane, PLEASE edit and let me know any corrections, etc. that need to be made.