|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Old Welsh Collier. |

|

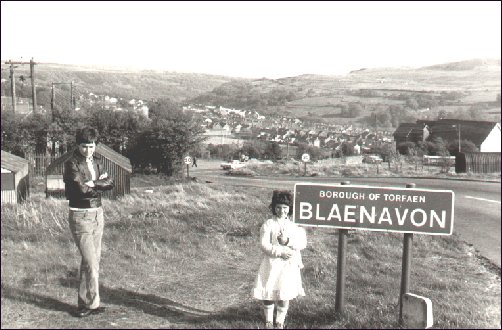

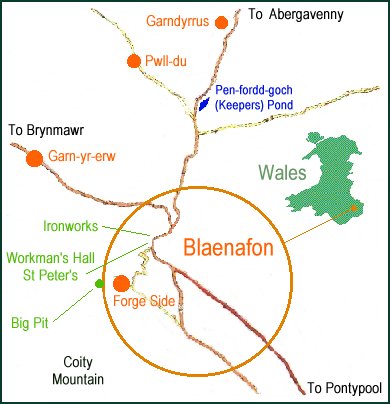

The Eastern Valley starts off by the sea at Newport and winds it's slow way up through Cwmbran, Pontypool and Abersychan, before coming to it's end at the Coity Mountain - under which one will find the venerable industrial town of Blaenafon. If you were to look here with just your eyes you will see the normal landmarks of a South Wales Valleys mining community - but if you look also with your heart, you will see the proud remnants of a once great industrial centre, and a strong people, born of the hardships of the mining and iron industry from which this town grew. My brother and sister, Andrew and Gillian, are here to welcome you to Blaenafon - as you would enter from the Abergavenny Road. This picture was taken in the late 1970's.

A few hundred years ago, this sleepy little town was just a tiny village, supplying timber and iron ore to the ironworks in Pontypool - until the start of the industrial revolution, the mountains that you can see in the background used to be thickly forested until all the trees were cut down for their timber. Then for a heady hundred years or so, the town changed dramatically and became a major centre for coal mining, and iron and steel production. It's coal was renowned as being one of the best in Britain and in demand for fuelling steamships and locomotives, and it's iron and steel was exported all around the world to feed the ever growing need for new railways and ships which were pushing back the worlds frontiers.

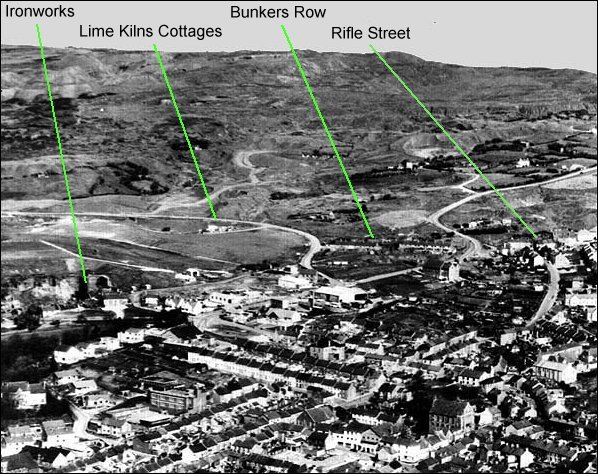

Between 1801 and 1921, the population of Monmouthshire increased from 45,000 to 450,000, and Blaenafon grew at a similar rate - 1,000 in 1800, 4,000 in 1850 and 7,500 in 1860. Although previous to this, most people in Blaenafon spoke Welsh, the huge influx of workers from around the UK and Ireland, meant that English became the main language. Of my family which centred in Blaenafon from the middle of the 1800's until just a few years ago, only the Thomas line seems to have been in Blaenafon as far back as I have researched so far. The other lines came in from Herefordshire, Somerset and other parts of South Wales. I never really ever lived in Blaenafon - the longest stay was around 2 months when I was around 10 years of age - though we visited many times to see our grandparents, aunties, uncles and cousins. My first memories are of lying in bed at night at my Nana and Grampa Price's house in the Lime Kilns Cottages - which have sadly been knocked down now - and listening to the wind whistling around the house after its journey across the town on it's way from sweeping off the Coity mountain. This is an interesting aerial photo of Blaenafon circa 1970. So much has changed in those few short years. I was so happy to get it as it let me fix back in my mind the relationships of those places which I remembered from early childhood - Lime Kilns, Bunkers Row and Rifle Street. Rifle Street was where my Nana and Grampa Thomas lived.  Mining is one of the major reasons for Blaenafon's strength. One hundred years ago, Blaenafon had no fewer than 7 different mines being worked. These being:

All of the mines were owned by the Blaenafon Iron and Steel Company. In their heyday, they were operating 16 collieries in addition to the ironworks, and by 1916 they were Europe's largest iron and steel company - employing over 12,000 people. They were acquired by Daniel Doncaster in 1957. Doncasters still have a plant in Blaenafon producing steel. My grandfathers were both miners. Leslie Thomas was a colliery hewer, and worked at Milfraen Colliery then Kays Slope and his last year at Big Pit. Caleb Price was a bricklayer in Big Pit. Many others in my family were also connected with the mining industry.

It was opened in 1860 as Kearsley's Pit, and became Big Pit in 1880 when the shaft was sunk much deeper. It closed 100 years later when the reserves became exhausted, and is now a Mining Museum where you can see how life really used to be - complete with a tour underground by one of the miners who used to work there. Blaenafon is quite a small, sleepy town now, but used to be very lively. As working in the furnaces was rather hot work, beer was very popular! At one time there were over 50 pubs in the town.

The hall was built in 1894, replacing a smaller one in Lion Street which had been operating since 1883. It is one of finest buildings of it's kind in the country, and was paid for by weekly contributions from the miners and steel workers at a cost of about 9,000 pounds.

The new works were started in 1840, and not finished until 1860. In celebration of this event they had a huge procession of 3,000 people and a volley of cannons, plus each worker was given 18 pennies and each child one shilling. By 1880 the works was developed to such an extent that it was considered to be the finest ironworks in the world. The iron industry was, however, declining, so the decision was taken to switch to steel production. This saved the company for a while, though the cost of the conversion plus the abundance of cheap foreign steel was heralding the death of the works. They were closed down in 1922 and the last blast furnace was dismantled in 1938. In the 1960's the National Coal Board sold the works to Blaenafon Council in order to reclaim the land. In 1972 the Department Of The Environment took possession of the land, and in 1974 started work on making the works into a museum. Above all else - Blaenafon made one very significant contribution to the steel industry. There was one major problem with most of the iron ore which was available - it had a high phosphorus content - which made the steel very brittle. In fact, only about 10% of the ore could be used. A justice clerk working in London - Sidney Gilchrist Thomas - was also an enthusiastic chemist, and had a cousin, Percy Gilchrist who worked in the laboratories at the works. Sidney made regular trips to Blaenafon in 1877 to help his cousin work on the phosphorus problem. Sidney eventually found the solution in a new type of furnace lining, the discovery of which made him very wealthy and famous. Unfortunately though, he died at the age of 34 of tubercolosis. Andrew Carnegie, a Scottish industrialist who made his fortune in steel in Pittsburgh, bought the patent for the Gilchrist Thomas improvement for 25,000 dollars in 1880. He then took it to Pittsburgh and made the works there the finest in the world.

It was built by Ironmasters Samuel Hopkins and Thomas Hill in 1804 and was consecrated the following year on St Peter's day. It was famous for the amount of cast iron which was used in it's construction. A great many of the graves there also employ iron tomb covers and the font was also iron. Hopkins and Hill are both buried here. Well, that rounds up our little tour of Blaenafon - which has hopefully given you some insight into the towns character and history, and maybe whetted your appetite for a visit when next you are in the area. In the meantime the links below will hopefully also give you some further insights... |

|

|