My Stay at the World's Highest Telescope

by Phil Rastocny ©Once inside the observatory, we were introduced to the 3 control room computers and explained their operations. ET runs communications programs and establishes data connections between MWO and the DU campus. HESS runs image-processing programs, controls the telescope’s cameras, and records the exposures. APOLLO guides and slews the massive telescope through the heavens. Apollo runs a version of Software Bisque's TheSky Level V. Loading all databases to this program paints stellar objects over the entire screen so densely that its otherwise black background turns a hazy gray.

MWO Control Room, from left to right, Apollo, Hess, and ET

Photograph by John Smith

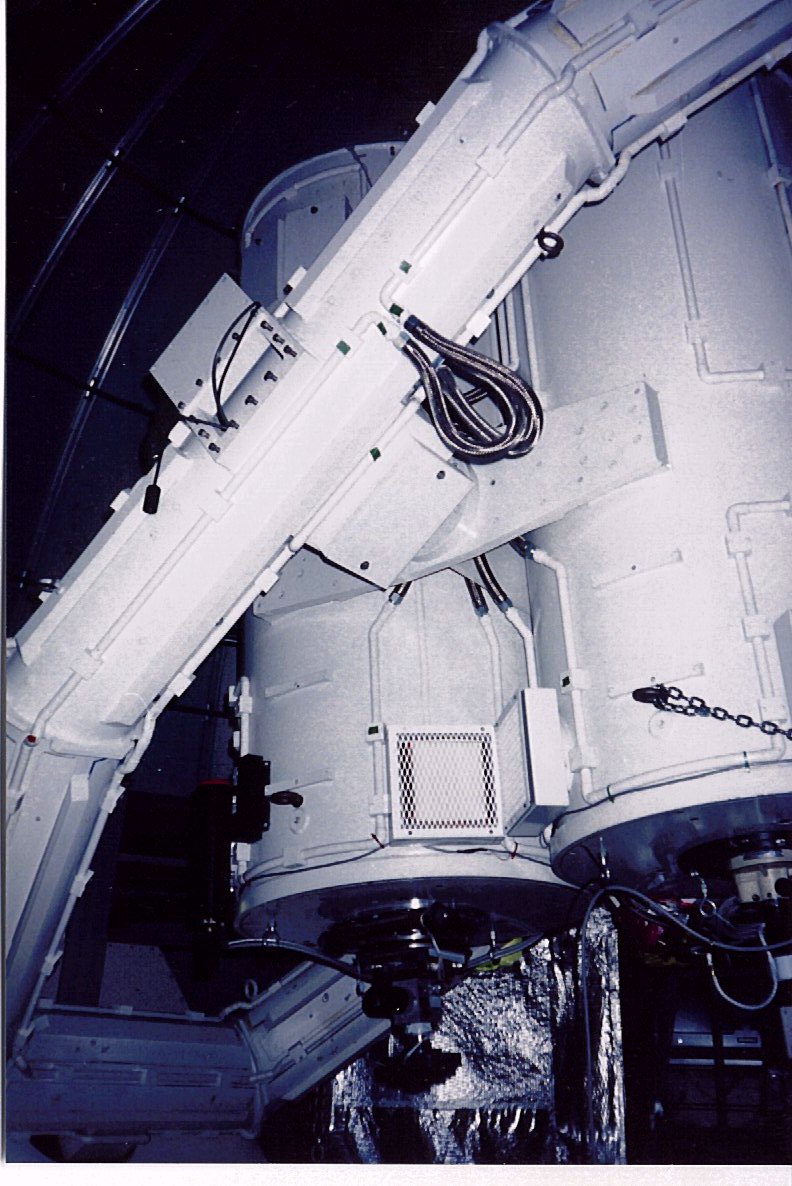

MWO binocular telescope showing V-tube (left) and IR-tube (right)

Photograph by Rick Foye and John Smith

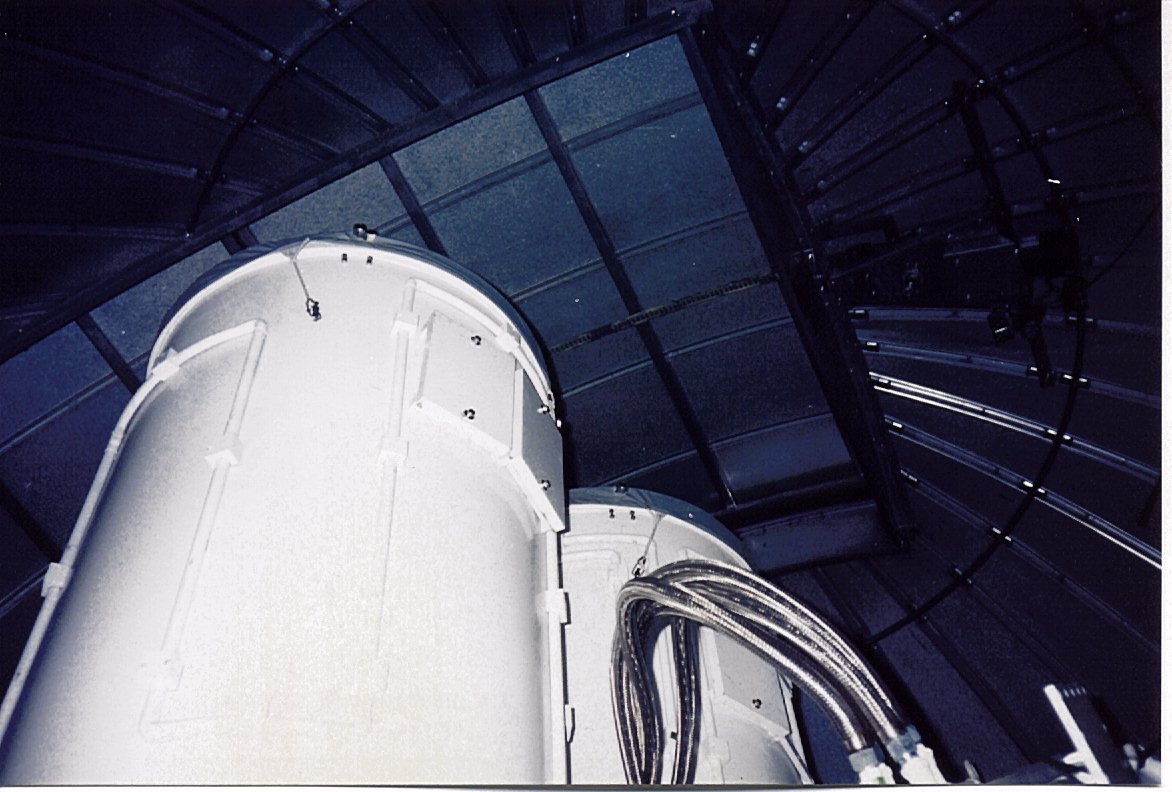

Dome slit of MWO

Photograph by Rick Foye and John Smith

Southeast telescope pad at MWO

Photograph by John Smith

All too soon, the moon rose and twilight came, ending a very, very thrilling first night. While driving down the mountain, the sun rose and details of the valleys below came into full view. An expansive 40,000-acre wilderness flowed to the south and joined other National Forests on two sides. I could see the mountain ridge that obstructed my home in the town of Conifer and my thoughts momentarily wandered to the modest observing sight in my 9,850’-high (3,000m) back yard. I thought that the seeing both here and there were quite similar and I was glad again for the choice I made in picking the location of my home. As the week wore on, I would change my opinion of my own little dark-sky site. I crawled into bed at about 0700 and dreamt of the wonderful things I had just seen and done.

July 21 – It was very cloudy and rainy today with a poor chance for observing this evening so two work details were organized. At 1400, two volunteers swept out the A-frame structure next to MWO in preparation for its renovation. At 1600, three other volunteers worked on the RA and Dec drive gears adjusting their meshing and greasing them thoroughly. Still others worked on the dome’s automated control, and the installation of a heavier motor for the dome's slit opener. It was a busy day and the night was yet to come.

That evening, we ventured back to the summit to be greeted by dense fog and light rain. Darkness came cloaking the mountaintop in a misty veil. Shining flashlights high into the darkness never penetrated these clouds. It seemed hopeless but ET linked us to weather maps that raised our hopes for later that evening. We settled in and watched as Thomas Bisque, owner of Software Bisque, demonstrated the virtues, features, and enhancements to his new software program, TheSky level V.

Periodically, one or two of us ventured outside to check the weather and about midnight, two of us witnessed a unique high-altitude weather phenomenon. There were two cars parked next to the observatory, one with its headlights on in this dense fog. Its headlights shone behind the other car casting its long light beams across the side of the observatory (see drawing below). In this 12’-wide (3.5m) space between the car and the observatory, the fog rolled eerily toward where we stood. Then suddenly, this back-lit fog began to swirl toward us. Swirling vortexes emerged in the foggy darkness looking like tiny, face-on galaxies with central black holes. These 1" (3cm) sized black holes pin-wheeled in a CCW direction, growing in a few seconds to 6" (15cm), and then dissipating. About 50 of these curious swirls appeared before the car moved off ending this fascinating observation.

Viewing position of weather phenomenon

Drawing by Phil Rastocny

Climbing the stairway and looking through the slit in the dome at about 0300, I saw some wondrous naked-eye sights. I saw M31’s central bulge taper outward to distinct, thin edges. Turning my head toward Cassiopeia, I saw the double cluster NGC869 with black sky between the two and its companion NGC957 with absolute clarity. Other objects seemed to jump down out of the sky and land on my eagerly awaiting eyes. Seeing these objects this clearly in the cold night air proved to me without a doubt as to why the best telescopes are this high. My Conifer dark-sky site now seemed woefully inadequate compared to this vantagepoint where naked-eye views of M31 only hint at a smudgy blur of stars with no particular shape. It is no wonder that the Hubbell space telescope is capable of getting the images that it does. This was an emotional experience that left me with a sense of awe I will never, ever forget!

During this same time, we shared the observatory with some scientists from the University of Alaska who studied a lightning-related weather phenomenon called sprites. This phenomenon randomly occurs during intense storms and sends small, beautiful salmon-colored energy bursts to altitudes as high as 59 miles (95 Km) above sea level (the upper limits of our atmosphere). Reported by pilots for years, these bursts plume into colorful clouds or flashes of light and are now being investigated by several groups. Sharing our humble accommodations with these pioneers of a new field seemed fitting since first light of this telescope was only one year ago. Both groups were in their infancy and both excited about doing their particular line of science.

All too soon the dawn came and we once again drove down the mountain. Tonight we seemed better acclimated to the altitude in that breathing and moving was not as tedious as in the previous night. As predicted, however, our visual acuity diminished and fainter objects that normally were observable faded somewhat into the darkness. We were also becoming used to the all-night work-hours of astronomers but we looked forward to getting into our beds.

Looking due south at dusk. Weather did not look promising

Photograph by John Smith

We took down all three computers, moved them around, performed upgrades, and reorganized the work areas in the control room. Shortly after midnight two of us selected images from previous observing sessions. We collected a cross section of planets, nebulae, and globulars to work with Software Bisque's CCDSoft image-processing software.

We shut down the computers at about 0230 and began to lock down the observatory for the night when suddenly the batteries gave out and all went black. It is amazing how dark it was and how quickly everyone found their flashlights. Since we were nearly ready to leave it seemed fitting that the batteries, not the weather, chased us off the mountain.

Driving down was interesting and challenging. Other astronomers in similar foggy conditions drove with their car windows rolled down with flashlights in hand to see the edge of the road. Another time someone walked in front of the cars with flashlights to guide the cars down the 14-mile (23Km) road back to the dorms. Fortunately, my car had fog lights. Adjusting them and the headlights down to a very low angle, we cautiously ventured down the hill. The fog was very thick to say the least and our little caravan crept slowly through the night. Idling along in first gear at times did not seem slow enough but then suddenly the fog broke and we virtually dropped out of the clouds. Whisps of fog and vapor beat against the rock cliffs as if some invisible ocean lay just beyond the road. Like some great surf crashing against a reef, streams of mist plunged upward streaking high into the sky forming striated gray curtains of water droplets. We made it safely down and looked forward to another night and one last opportunity for clear skies.

July 23 – Again the weather was formidable and it now seems as if Colorado’s monsoon season was here to stay. On this last night, five of us crept up to the summit hoping for the usual break in the clouds in the early morning. About midnight, Dr. Eugene Wescott from University of Alaska loaned us two videotapes to watch about sprites. The first was a 5-minute color promotional explaining their work and the second a 20-minute B&W showing an amazingly intense storm in TexArkana with virtually hundreds of sprites firing off into the upper atmosphere. Dr. Stencel then took us back into the observatory dome and pointed out to us a change in the welding of the north telescope-pier’s top plate that caused this scope's polar alignment error. We also watched some of the earlier-recorded video footage of Jupiter, Saturn, and the moon. The weather never did break and regretfully we all came down at about 0300.

July 24 – Time to leave. As we packed up the cars and said our good-byes, there was an intense feeling of pride and accomplishment knowing that the only tasks that remain to bring this new telescope into its prime are polar alignment and a minor optical tube assembly alignment. Our combined efforts raised this instrument from the level of infancy to that of near maturity, something that we were thrilled to do. We all saw some interesting objects and touched some phenomenal observing equipment.

Being at MWO has personally rekindled my serious interest in astronomy and I am truly thankful for that. I also want to thank Dr. Robert Stencel, Terry Chatterton, Marc Jones, the University of Denver, Tom Melscheimer, Thomas Bisque, and all of the others who help make this stay so enjoyable despite the cloudy weather. I hope to see you all at some time in the future, probably at a star party or observatory near you!

MWO , Altair, and Lunar conjunction, July 20, 1998

Photograph by Brad Hoehne

The Meyer-Womble Observatory home page can be found at http://www.du.edu/~rstencel/MtEvansBio Brief

Information about the University of Alaska’s work with red and blue sprites can be found at http://elf.gi.alaska.edu/sprites.html/

New Mexico Tech has also studied sprites and has monochrome frames from a video shot in 1998 that can be viewed at http://ibis.nmt.edu/sprites/HighSpeed.html

Scientific American magazine ran an article on sprites in August of 1998 that can be viewed at http://www.sciam.com/0897issue/0897mende.html

Phil Rastocny is an undergraduate of Oklahoma State University and graduate of the Stevens Institute of Technology. He works as an IT Manager for Lucent Technologies, Bell Labs Innovations. He and his massage-therapist spouse, Althea Rose, have lived in and enjoyed the high, dark skies of Conifer, Colorado, for the past 19 years. Phil is primarily interested in the astronomical phenomena of dark matter and variable stars, and teaches classes on buying your first telescope and beginning astronomy at local institutions. Phil can be contacted at arose@denver.net or at 32094 Christopher Lane, Conifer, CO 80433 USA.

Copyright Notice

Copyright © 2000 by Phil Rastocny, all rights reserved. No portion of this article or its photographs and drawings may be reproduced in any way without the express written permission of the author. Please contact Phil Rastocny at arose@denver.net for comments and inquiries.