From Organic to Diasporic Intellectual

Italian political theorist Antonio Gramsci wrote extensively on the role of the intellectual in public life. Contrasting the "traditional" with the "organic" intellectual, Gramsci saw the former as educated to maintain the status-quo of the powers ascendant at that time, while the latter "organic" intellectual rose up from the ranks of the subaltern classes in order to act as a mouthpiece for their concerns and empower them with a voice in the larger body politic. The idea of the "organic intellectual" has been influential in the thinking of many theorists since Gramsci. More recently, another view of public intellectuals has become current, i.e., the "diasporic" intellectual. Unlike the organic intellectual who remains rooted in the community from which he/she emerged, the diasporic intellectual moves between nations, cultures, languages, and other "positions." Indeed, the "position" as well as the "location" of the diasporic intellectual is often difficult to pin down. From the scattering of the Frankfurt School to the postcoloniality of Said, Spivak and Bhabha to the work of Stuart Hall (See Chen) in cultural studies, the diasporic intellectual works from the perspective of exile and/or immigration, from the pain as well as the freedom of displacement.

In the character of Rubie, TO LIV(E) and CROSSINGS create a fictional representation of the process of transformation of a concerned, educated, "organic" intellectual into a "diasporic" intellectual. Like the activist Elsie Tu, who appears in TO LIV(E) as the disillusioned British missionary/housewife turned urban activist, Rubie in CROSSINGS leaves behind her roots in Hong Kong to take up the role of community activist and spokeswoman in New York City.

In this way, the character of Rubie (played by Lindzay Chan in both films) acts as the other bridge that links TO LIV(E) and CROSSINGS together. Although it is never made explicit that a single, unified "Rubie" is exactly the same character in both films, the two Rubies clearly function in the same way in both texts and in most ways can be taken as a single character.

However, given that Rubie may be a single character does not belie the fact that she is presented as a conflicted, often contradictory presence in the two films. As such, she represents all those conflicts of identity central to the thematic dynamics of both films. On the one hand, her roots are found among the poorer quarters of Hong Kong society. During a scene depicting a rather uncomfortable family gathering, her father digresses on the family history as squatters selling groceries, moving from one temporary housing development to another, threatened by floods and ravaged by fire, as well as by corrupt officials demanding kickbacks for a business license. The family is taken under the wing of Elsie Tu, who uses her influence to set the family up in a legitimate shop.

From these lower middle class, small merchant roots, the children emerge as full-fledged members of Hong Kong's professional/intellectual sector. Rubie is a journalist, who becomes a community activist/ social worker in New York. Her brother, Tony, is a highly skilled radiologist, and the eldest brother has successfully established himself in Canada. Unlike their parents, the children have the education and skills to move outside a Chinese environment into a global, English-based, diasporic community of post-colonial professionals and intellectuals plying their trades along the path of the former British empire--from Canada to Australia, the United States, and South Africa. They come from an impoverished China, but they move now in other circles. Ironically, it is the experience of colonialism (here embodied by the personal patronage of former British missionary Elsie Tu) that makes this movement and this upward mobility possible.

Rubie, at one point, pays a visit to her family home and shop. It is filled with the details of a marginal, small merchant's existence, including the outdoor tables and shop, the bare floor of the main living room, the worn table used as part of the elevated family shrine, the special, round table top brought in for the family gathering, the padded, old-fashioned vest and trousers worn by her mother. It becomes clear Rubie has not always led a solidly bourgeois existence. It may seem that the casting of the Eurasian actress Lindzay Chan in this role and the inclusion of her reading from the lengthy series of letters to Liv in English contradicts this picture of Rubie's humble origins. Not only does this contradiction alienate the spectator from the character, but it also serves to highlight the indeterminate identity and position of the people of Hong Kong as Chinese British subjects, as educated and superstitious, as Western and Asian, as poor and struggling and established and well-to-do.

Rubie speaks in two voices-- in fluent Cantonese and in impeccable British-accented English. Like Hong Kong itself, sometimes she looks Western, British, Caucasian and sometimes she looks Chinese and Asian. For example, in TO LIV(E), she reads several of her letters directly addressing the camera in medium shots, seated against a British union jack, the American stars and stripes, and the flag of the People's Republic of China. Interestingly, when she is shot in front of the Chinese flag, the lighting of her hair accentuates its reddish highlights. The light allows her to blend in with the flag at the same time it emphasizes her distinctiveness as a Eurasian performer. Rubie sometimes plays the role of a British subject, the role of an ethnic Chinese, the role of an Asian American immigrant, and, most importantly, the role of a character of an indeterminate identity.

In CROSSINGS, Rubie tells another story about her origins. She explains her Caucasian features as a throw back to the Tang Dynasty when she must have acquired some European ancestor from exchanges on the Silk Route. The fact that Rubie's ethnic and cultural hybridity needs to be explained at all is itself telling. Addressing the reception of TO LIV(E), Evans Chan has commented on critics who demand an "authentic" Hong Kong subject:

One controversial issue the film does occasion seems to be the establishment of 'the (post-)colonial subject,' hence the problematic status of the letters which are written in English…I can understand the film's identity being characterized as schizophrenic, however, the notion that English is alien to the film's yet-to-be-post colonial identity is curious. After all, English is still primarily the official language of Hong Kong, where three major English dailies and two English TV channels permeate the everyday life of the educated class. Legal proceedings are conducted in English and Chinese politicians make speeches in English at the Legislative Council. If an average Hong Kong citizen speaks little English, that proves how linguistic schizophrenia may turn out to be a colonial legacy that will take some time, provided the will, to eradicate.

…That Hong Kong is a linguistically hybridized being is a fact that the film is not obliged to transcend. (p. 5)

Rubie, then, functions as the voice of Hong Kong, expressing, through her letters in TO LIV(E) and her diary and appearances on the television news as an "expert" insider in CROSSINGS, the hopes and fears of her community. Her identity and the identity of that community may be difficult to pin down as they slip among Britain, America, Hong Kong, and China, between the lower small merchant classes and the upwardly mobile professionals, between a "traditional" older generation and a more urbane younger one. Rubie, however, manages to embody this cacophony of "voices."

Rubie is more than a "mouth," however, she is also an "ear." Throughout TO LIV(E), the "ear" appears again and again as a motif associated with both Hong Kong as a place and Rubie as a character. Near the end of the film, the painting John has been working on throughout is revealed to be a picture of an ear. To break the tension of her brother's departure, John orchestrates a Vincent Van Gogh practical joke with a bloody cloth over the side of his face and a fake, severed ear. Still unsteady from having just prevented her brother's attempted suicide, Rubie faints at the sight of the phony severed ear and falls into a dream in which the ear reappears.

In her last letter to Liv, Rubie refers to George Bernard Shaw's trip to Hong Kong in 1933 as follows:

Hong Kong 1933 didn't seem to exist for Bernard Shaw, except as a bad ear messed up by the British for communication with China. And an imperfect ear we've always been--as a bastardized link between a China weighed down by tradition and the clamorous demands of modernity. (p. 61)

Throughout both films, Rubie is this same kind of "bastardized" ear, understanding English (and, through that, the perspectives of the British, American, and international community represented by Liv Ullmann) and Chinese (through Cantonese, she understands the Hong Kong Chinese and, through Mandarin, she understands the "greater China" community). Her trained, cultivated ear can appreciate experimental satiric theatre as well as Italo Calvino and the films of Ingmar Bergman. Like the organic intellectual, she can "hear" the marginalized and dispossessed as well as the bourgeoisie. Like the diasporic intellectual, she can "hear" the subtleties of the official and unofficial proclamations of various governments and other institutions.

Indeed, Rubie moves in a social world that is marked by this cultural and linguistic hybridity. This "floating world" of transnational, petit bourgeois labor includes artists, professionals, activists, journalists, among others, who are young, educated, culturally astute, and mobile. Although business people, artists, theatrical performers, and professionals like lawyers and doctors find their way into commercial popular culture, intellectuals seldom make a serious appearance in the cinema. (see Ross)

In both TO LIV(E) and CROSSINGS, Rubie's circle

is rich in characters who are involved in a variety of artistic

and intellectual endeavors. Again, like Bergman and Godard, Chan

favors educated, thoughtful, cultured protagonists. In TO LIV(E),

Rubie's boyfriend John busily works on his paintings and reads to

Tony from Calvino's Invisible Cities; Rubie attends

experimental dance performances ("Exhausted Silkworms"

on Tian'anmen, "Nuclear Goddess" on Daya Bay, China's

first nuclear power plant,

constructed in suspiciously close proximity to Hong Kong); Rubie's brother's girlfriend, Teresa (Josephine Ku), relaxes as an experimental video piece plays on her television; Rubie quotes George Bernard Shaw and The New York Times in her letters to Liv.

This world is not only cultured, but cosmopolitan. Rubie's friends and relatives are part of a global society. In addition to Rubie's elder brother in Canada and younger brother on his way to Australia, Rubie's circle includes the interracial couples (Chris and Leanne, Trini and her Caucasian husband), ex-patriots like Elsie Tu, overseas Chinese like Tony's old flame, Michelle, on a trip back from the United States, and many others.

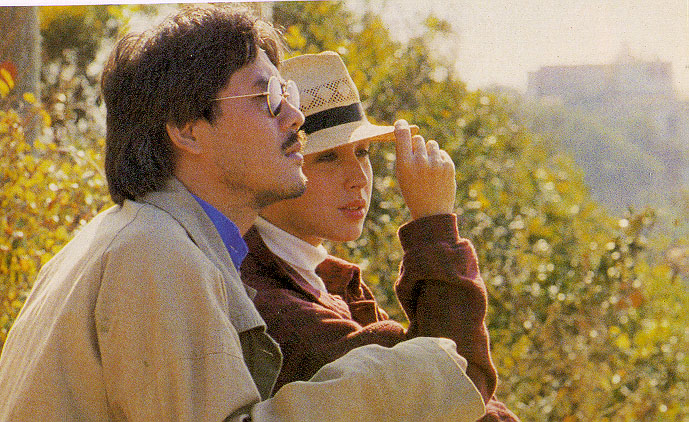

CROSSINGS extends Rubie's circle even more. Again, Rubie functions as a bridge between various groups. Rubie befriends Mo-Yung (Anita Yuen), who is an illegal visitor to New York in search of an errant boyfriend. In this case, Mo-Yung acts as a fulcrum with Rubie on one side of the scale and Mo-Yung's gangster boyfriend, Benny (Simon Yam), on the other side. Rubie and Benny battle over Mo-Yung. Rubie tries to divorce her from her destructive relationship with Benny, and Benny tries to find her either to use her to get to a cachet of drugs or to take possession of her heart.

Artists, writers, and filmmakers have a long history of using criminals and gangsters as more than objects for social or psychological studies. Indeed, filmmakers as diverse as Godard, Bresson, Fassbinder, John Woo, and Ho Hsiao-hsien have used petty gangsters as cinematic "alter egos," as mouthpieces for more than the concerns of petty hoods. The character of Benny is crafted in this tradition. It is difficult to tell whether Benny is a drug trafficker and pimp masquerading as a fine art photographer or a sensitive artist, doing a photo-essay, "Countdown to 1997," who toys with a gangster identity. The photographs Mo-Yung spreads on her bed are as concrete as the drugs Benny's other girlfriend Mabel cleans on their dining room table. Both serve as visual manifestations of Benny's character, although it must be granted that the white powder carries more narrative weight than the photographs.

Since the silent era, the gangster has been used in film to concretize and contemplate economic relations. He is an outsider who serves as a mirror for the society he haunts. Like the intellectual, he has been produced by and has arisen out of a certain milieu, but he is deviant, an implicit critic of the society that produced him. At this point in time, the gangster increasingly functions as an emblem of transnational economic relations. In CROSSINGS, the comment is made that Marco Polo brought two elements of Chinese culture to the Italy, i.e., pasta and the Mafia. Both food and crime continue to cross borders to exert their influence transnationally. The gangster is a sinister citizen of the world. He has become part of the Diaspora--along with intellectuals, legitimate merchants and business people, students, skilled workers and professionals (particularly in medicine), etc.

Benny is a hybrid, a gangster-intellectual. Like Rubie, he has humble roots in Hong Kong's under-classes; however, he transcended his origins through the drug trade rather than through painting like John, the medical profession like Tony, or journalism/social work like Rubie. He is a fitting object for Mo-Yung's "wrong love," since the uncertainty of his relationship to her finally comes out on the side of genuine emotion. After using her to smuggle drugs and denying any feelings for her to Mabel, he gives up his freedom and takes a police bullet in the back when he realizes Mo-Yung is having a miscarriage because of his reckless attempt to escape from the law. More than the tenderness in his relationship with Mo-Yung elevates him within the narrative, however. CROSSINGS portrays Benny as a pensive gangster who can appreciate African traditional art, who has a certain flair for fashion, and who looks at his trade in historical terms as a response to the British push to sell opium in China that occasioned the Opium Wars. Since America supposedly encouraged the trade further through its involvement in the politics of the Golden Triangle, Benny justifies his trade as a political act of resistance—getting back at American imperialists by poisoning the population through the drug trade. When Rubie meets Benny in prison, however, he has again taken on the persona of the hardened criminal, the face he used in his interactions with Mabel. Aside from a few brief moments with Mo-Yung, Benny never manages to voice a substantial social critique.

The character of Mo-Yung comes a bit closer. Unlike Benny, Rubie, and her relatives, Mo-Yung was born in Suzhou, in mainland China, into an educated family, descended from unassimilated non-Han invaders centuries ago. Her father, an engineer, was forced to kneel on broken glass during the Cultural Revolution. Taking the family away from the excesses of China’s political campaign, Mo-Yung’s family found itself downwardly mobile in Hong Kong, the father finding work as a carpenter. Mo-yung’s name marks her as a mainlander, as specifically from Suzhou. When she asked to change it as an adolescent, her father questioned her desire: "Are you so eager to conform? To assimilate?" Thus, even in Hong Kong where she grew up, Mo-Yung is an outsider. The fact that she will leave is taken as a given by most in the film. Her family pushes her to marry a Canadian immigrant to ensure another escape from the People’s Republic after 1997. She has already rejected a plan for her to immigrate as a nurse, since she fears that, as a foreign nurse, she will be required to work exclusively with AIDS patients, under conditions she fears will not preclude her being infected. Finally, following Benny, Mo-Yung becomes an illegal alien in New York, sucked into his world of transnational trafficking in drugs and prostitutes. Mo-Yung is left to drift in New York until she meets her tragic end.

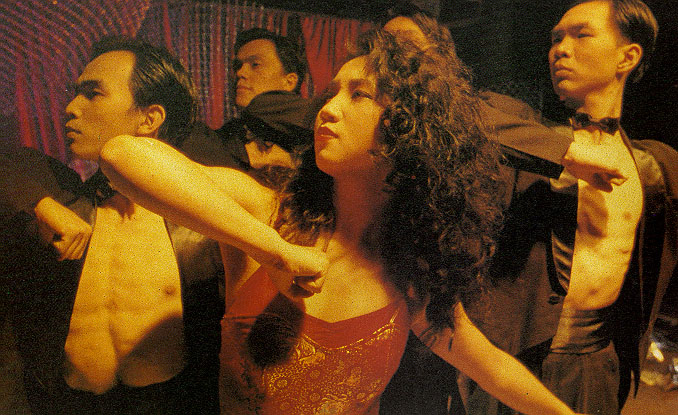

As in TO LIV(E), the voice in CROSSINGS is given to Rubie. Divorced now (presumably from John) and with a child left in Hong Kong, Rubie has been severed from her roots in Hong Kong's lower middle classes to find herself administering to a similar community of overseas Chinese in New York. At one extreme, in her work in a community clinic, Rubie sees illegal immigrant women brought in to work in the sex industry in New York, including some who become infected with AIDS. She also becomes involved in the edges of the illegal drug trade through her relationship with Mo-Yung. At the other extreme, Rubie moves in a very different social sphere represented by one of her close male friends, a Mandarin-speaker. This character is gay, with a Caucasian boyfriend. He does experimental dance, dressed as a female character from Beijing opera, to a pop music beat, in a disco frequented by Asian transvestites. He speaks in Mandarin, she responds in Cantonese, and both translate for the American boyfriend in English.

These two cultural spheres overlap throughout the film, and come together most dramatically at Mo-Yung's funeral. In this scene, the dancer performs a piece in which his defiantly thrown back shoulders, high aerial kicks, and simple, male attire work in concert with wreaths denouncing violence against Asians from various community groups. Looking at this scene in conjunction with the scene featuring a similar dance performance, "Exhausted Silkworms," in TO LIV(E), underscores the two extremes used to position the characters and events in both films. "Exhausted Silkworms" reenacts the violence of Tian'anmen and the funeral performance memorializes Mo-Yung, not as a victim of "wrong love," but as a victim of random, anti-Asian violence in the United States.

Here, the position of the global Hong Kong community hits two, violent terminal points: one in the political fear prompted by the suppression of the 1989 Tian'anmen demonstrations and the other in the social fear of racial violence in New York City. Caught between these two violent extremes, Rubie tries to sort out her own position and identity. At one point, in CROSSINGS, Rubie is on an elevated train platform, putting on lipstick. Taking the position of a stalker, the hand held camera moves in on Rubie. When she is framed in a close-up, Rubie turns and runs. The camera then turns to reveal Joey (Ted Brunetti), who addresses the camera directly, "Blood must flow. What if I push you on the tracks?" The film cuts away to a street person screaming on the sidewalk as the elevated train screeches in the background. A frightened Rubie is shown escaping on the train; a musical bridge connects this scene with a scene of Rubie writing in her journal in her apartment. She recalls a similar incident that happened the week before. The flashback shows Rubie reading the paper on the elevated platform. In this case, rather than taking the point of view of the stalker, the camera takes Rubie's perspective as an African American man directly confronts the camera (i.e., Rubie) and lashes out at her, "Man, I hate you Japs…" He rambles on incoherently about a blood reckoning to be paid. Back at her apartment, Rubie continues in her diary: "Would it have helped if I’d told him I’m not Japanese, but a Chinese from the British Crown Colony of Hong Kong? Where would I have felt protected? Britain? China?"

While the cosmopolitan world of Hong Kong or New York promises a certain freedom associated with the hybridity of the metropolitan experience, it also represents a world in which identity is cast adrift and there is no safe haven. Joey's psychosis, which these parallel scenes show is not uncommon, revolves around a mis-recognition of the Asian woman. This mis-recognition operates on several levels. Joey stalks Rubie, but, under the assumption that any Asian woman would satisfy his blood lust, he kills Mo-Yung. Joey is driven into this delirium by an encounter with an Asian transvestite, whom, in M. Butterfly fashion, he mistakes for a woman. Indeed, Joey mistakes all the Asian women he encounters, from his prostitute girlfriend in Thailand to the newly arrived mainland Chinese prostitute he visits in a New York massage parlor, for his "dream girl," submissive, compliant, subservient, and posing no threat to his own uncertain sexuality. In his delirium, Joey even mistakes Mo-Yung for a dummy, raving happily about passing the "test" to see if he could tell the difference between a real person and a mannequin. His racism levels all identity, turning all Asian women into objects. When Joey's sister tries to explain her brother's mental illness to Rubie at Mo-Yung's funeral, Rubie's only response is, "It could have been me! Don't you see, your brother was stalking me. It could have been me." Between Trini's analysis of her position as a "British object" in TO LIV(E) and Joey's interchangeability of Asian women as objects in CROSSINGS, the voice of the diasporic intellectual becomes silent. If Rubie's role as an intellectual is to listen and speak for her constituency, she (and, perhaps, the filmmaker who created her) ends up silent in between two worlds marked by violence.

It can also be noted that Joey does not inhabit a world totally dissimilar from Rubie's. Like Rubie, he, as a public school teacher in New York, is part of a class of educators, social workers, media workers, etc., who can be loosely grouped as intellectuals. He has a secure job; the principal of the school laments the fact she cannot fire him, even though he alternately brutalizes and ignores his students, because he has tenure and is "competent until proven incompetent, sane until proven insane." He has disposable income to travel to Thailand. Also, like Rubie, he seems to be upwardly mobile, living with a sister whose accent and demeanor point to working class roots. If Benny represents the intellectual as gangster and Joey represents the intellectual as madman, Rubie represents the intellectual as something different; i.e., as a woman within the Diaspora.

Continue to Part VI: The Ear Is Attached to a Woman