The Second "Happy Time":

The Loss of the Putney Hill

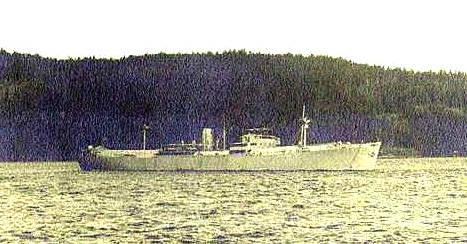

Alan Shard was a young Lancashire lad who joined the British Merchant Navy as an Apprentice Deck Officer in June 1940, just at the time of the Fall of France. Alan's first ship was the brand new British freighter, the MV Putney Hill and after he signed aboard, she set off on her maiden voyage to the west coast of Canada. By the time that Putney Hill was ready to return home across the Atlantic as part of Convoy HX-72, it was September 1940 and the U-boat situation on the Atlantic had worsened. Newly-established U-boats bases on the west Coast of France made it possible for the U-boats to range deeper into the Atlantic and strike at convoys in coordinated groups known as wolfpacks. By choosing mid-ocean areas where Allied naval escort protection was weakest, the U-boats experienced little opposition. It was the beginning of a six-month period that U-boat crews referred to as "The Happy Time". As HX-72 crossed the Atlantic in September 1940, it was one of the first convoys to be savaged by the U-boat wolfpacks. That time, Putney Hill was one of the lucky ships which got away, but, her luck would run out in June 1942, just at the end of what the Germans called "The Second Happy Time" or "Great American Turkey Shoot" when U-boats sunk hundreds of unescorted ships just off the American Eastern Seaboard and Gulf of Mexico coast. The following story written by Alan Shard is an account of Putney Hill's tragic loss. The initials "F.N.I" after Alan's name stand for "Fellow of the Nautical Institute". |

|

by Alan Shard, F.N.I.

The date was June 25th, 1942. The 5216 gross reg. ton motor vessel

Putney Hill of

London

(D.W.Hughson,

Master)

was en route from CapeTown to New York

to pick up a cargo of

military equipment for Russia. She was approximately 500 miles north

of

San Juan, Puerto

Rico,

proceeding independently on a zig zag course at 10 knots. Lying

in wait for just

such an opportunity, (convoys had not yet been established by the

Americans on the

U.S.Eastern Seaboard due to

Admiral King's

aversion to British

tactics) was

Kapitanleutnant Rolf Mutzelberg,

Knights Cross with

Oak Leaves, in

U-203 a Type VllC U-Boat

of 761-tons displacement, surface speed 17 knots, submerged speed

7 knots.

The time was 2325. It was a brilliant moonlit night, warm, with little breeze and slight sea and swell. The lookout in the port wing of the bridge was a young Apprentice from Radcliffe, Lancashire, who was scanning an area from right ahead to right astern on his side. The Third Mate was keeping a similar lookout on the starboard side and an Able Bodied Seaman at the wheel. The fourth member of the watch, on Standby, had just made the coffee for the Middle Watch coming on at midnight. (Coffee on a British Ship in wartime consisted of throwing a few handfuls of grind into a converted 5lb jam tin with a wire handle and letting it stew on the galley stove). The Standby man came up on the bridge to check the time before he called the 12 - 4 watch at 2330. As he left the wheelhouse to go below, the Apprentice enquired of the time. With a slap on the back, the Standby man replied 2325 and simultaneously both of them were blown into the air from the blast of a tremendous explosion at the waterline in Hold No. 3, slightly aft of the bridge structure. The reverbrations echoed through the empty holds like a giant hammer blow from Thor and Putney Hill went dead in the water. Neither of the two were hurt and they donned life-jackets immediately. Smoke from the explosion hung over the decks. The Captain came running out of his cabin on the Lower Bridge Deck and as the ship had now taken a heavy starboard list, he ordered 'Abandon Ship'. The Apprentice wondered why he had not seen anything out there on the port side and figured the torpedo must have come down a moonbeam reflection in the tropical waters. It was later discovered from the U-boat War Log that the first torpedo (also unsighted) missed. The two lifeboats on the portside of the ship were useless, having been blown inboard against the funnel, so everyone ran to the starboard side which was almost at sea-level. The Apprentice was carrying an old army gas mask case made of canvas known as the 'grab bag' in which he kept his Merchant Navy Identity Card, a Mars Bar, extra pair of socks, some private papers and his camera. He threw them in his designated Lifeboat No.3 which was already in the water and swarmed down the falls to join 15 others. The lifeboat was a clinker built wooden craft which had not been in the water since he joined Putney Hill two years earlier in June 1940. Consequently, the seams were open to the sea and she soon settled to the 'gunnels'. Everyone baled furiously, the Apprentice even using his shoes as a container. Several men from the smaller lifeboat No.1, which had capsized, now endeavoured to climb into the waterlogged boat with the result that this one also capsized throwing all hands into the 'drink'. The 'grab bag' was lost in the exodus. The ship was now down by the head, but without the heavy starboard list. The answer dawned that the torpedo must have struck in the port deep tank midships, which held several hundred tons of ballast. This ballast was released in the explosion causing the ship to list immediately, but now, due to the fact that the starboard deep tank ballast was flowing through to the port side and in effect equalising the situation, the ship eventually became upright. This new state of affairs was not lost on Kaptlt. Mutzelberg who surfaced in order to execute his next move. No shots had been fired from Putney Hill's 4 inch stern gun as the acute angle of list had rendered it useless and all hands had already left by the time she righted. The Apprentice had never swam more than 50 yards in his life, but wearing his life-jacket, struck out for a life-raft floating a short distance astern. Several others had the same intention and eight clambered onboard. During this short swim he was stung by a 'Portuguese man-o-war', but felt nothing at the time. It later developed into a rotting hole about the size of a Canadian quarter which necessitated hospital attention in New York. The life-raft was about 8 feet square and consisted of wooden planks enclosing metal airtanks with a depression across the centre for survivors to set their feet whilst facing each other. Someone pointed to a man hanging on to the propeller which was clear of the water. It was the Assistant Cook and he was never seen again. The Putney Hill was lying like a ghost ship on the gentle sea, the silence punctuated by occasional loud bangs as various bits of the structure gave way under the increasing pressure. Without warning an incendiary shell hit the funnel and started a fire. It was followed by a further sixty three shells into the hull, counted by those on the life-raft from their grandstand position. Well at least Mutzelberg had allowed the crew to leave the stricken vessel before opening up with his deck gun. At approximately 0130 hours on June 26th, 1942, Putney Hill became almost vertical and still burning slid beneath the sea, bow first. The men on the raft were left alone with their own unspoken thoughts. The Apprentice was thinking probably the same as the others. What next ! ! They were not left in doubt very long. U-203 eased out of the gloom and approached the life-raft. A voice from the conning tower, in perfect English, enquired of the whereabouts of the Master. No-one knew, but if they had, the Apprentice was sure that he would have had great difficulty in not pointing him out, such was the miserable time that he and the other three apprentices had suffered at the hands of a regular Captain Bligh, but that was another story to be told at a later date. The U-Boat picked up a lifebuoy and moved off into the darkness after establishing where the ship was from and the nature of her cargo, which of course was nil, being in ballast. Again they were left with their thoughts, when suddenly the U-Boat re-appeared and to everyone's amazement they saw on the foredeck one of the apprentices. "What the hell is Hancock doing onboard the sub", said the Second Mate who was senior officer on the raft. By now the wind had risen and the sea was a little choppy, so the U-Boat could not get too close to the raft. The Commander called from the conning tower and requested that someone from the raft should come to him and assist the apprentice back to the raft as he could not swim. Without hesitation John McKenzie, the Second Mate dived in, swam to the submarine and escorted the youth back to his fellow crewmen. The apprentice was besieged with questions and basked in the 'limelight' in the middle of the night as he told his story. When the lifeboat capsized he was able to grab and hang on to an oar. He was apparently joined by a young Royal Navy DEMS gunner, Jeffrey Banks aged 20 of Northophall, North Wales, but the oar would not support both and in the ensuing squabble the gunner was lost. After some time in the warm waters of Latitude 24.20 North, Hancock found himself in the direct path of the U-boat as it searched for the Master. As it cruised by him at a couple of knots, the apprentice grabbed the ballast intakes, was sighted by sailors on the deck and hauled onboard. The Commander quizzed him at some length, but as a mere apprentice he knew nothing of the codes and naval orders etc, so arrangements were made to return him to his shipmates. Before he let him go, the Commander stated that if he was eventually rescued, that he should not return to the Merchant Navy, for if he was caught again the ending would not be as pleasant. Needless to say, all four apprentices were back at sea again within fourteen weeks of the loss of the Putney Hill. The most startling thing that Hancock recounted was the fact that Mutzelberg knew his hometown of Chelmsford (prior to the war) as well as he (Hancock) did. Another item, which got him into a spot of bother with the Naval Officer who interrogated him on his return to London, was the fact that he could not name the brand of cigarettes given to him by a member of the U-boat crew. You see, he returned them to the sailor when it became obvious that he would have to get back into the water and ruin them. Of course the Admiralty were interested in the brand, to see if they could possibly pinpoint at what port in Central America the U-boats were being supplied. Before saying 'Auf Wiedersehen', the Commander gave us a rough position as 485 nautical miles north west of San Juan, Puerto Rico and wished us luck, to which some wag of a Liverpool fireman shouted "how about a tow to the nearest island?". We all ducked at this effrontery, but no retribution was forthcoming. When dawn broke, the men on the raft saw at some distance the two lifeboats which had been righted and sails rigged. After some arm waving the raft was sighted and the largest of the two lifeboats came alongside in charge of the Master. Before leaving the raft, the men unscrewed the lids of the metal tanks marked 'Biscuits' and found them empty. Seems they had been rifled by persons unknown at the last port of call, Suez. However, the water tanks were still intact and the contents were transferred to the lifeboat. Heads were counted and the

The Apprentice was dressed only in a singlet and a pair of naval bell bottom trousers, but the nights were bearable in contrast to the broiling daytime temperatures. A piece of torn canvas from the lifeboat cover was utilised to cover three of the Apprentices until the Third Mate, a hulking Dane, decided to take it for himself. He was big so he kept it. On the seventh day the Fourth Engineer, Kenneth Cowling, aged 28 of Newport, died in the Master's boat. His brother, the Third Engineer, was also in the same boat. The Fourth Engineer had been on watch in the engine-room when the torpedo struck and he was burned over two thirds of his body by hot oil from a burst pipeline. With whatever prayers the shocked group could recall, his body was put over the side after his brother had removed his gold wedding ring. Someone said they saw a shark. On the morning of the ninth day a puff of smoke was sighted on the horizon as HMS Saxifrage, a corvette heading for her West Indies Station, revved up to full speed and bore down on the boats, at first mistaking their sails for a U-boat on the surface. All hands clambered up the scrambling nets to wild shouts of joy. Again another co-incidence, one of the corvette's sailors came from the next town to the lad from Radcliffe and he gave him his own bunk for the night. Next day Saxifrage arrived in San Juan, Puerto Rico where the survivors were taken ashore and rigged out in a motley selection of donated clothing. The Apprentice's luck was a pair of white chalk striped green pants and a pink shirt. He was more concerned with what he would look like going back home in an outfit like that than he had been on the previous 10 days. That night in the Hotel, the survivors experienced their first earthquake!! What a welcome for shattered nerves. Later, the survivors were issued a more conventional suit albeit a tropical one and sent passenger on the Veragua a United Fruit Co. vessel to Norfolk, Virginia, thence to New York for a glorious three weeks being entertained by Gotham's high society. The British Apprentice Club run by the famous Mrs. Spalding was an oasis never to be forgotten. Then back at sea again out of Boston as DBS (Distressed British Seaman) on the Norwegian whale factory N.T.Nielsen Alonzo where the Apprentice and one other had the total misfortune to be the only survivors of the Putney Hill to be with the old Skipper for the voyage to Greenock and home. That trip is another story of ropes end threats etc. One day whilst having 3 o'clock tea in the saloon, the Apprentice asked his shipmate to pass the marmalade, with the intention of spreading it on a cheese cracker. Our Captain spoke up in a cabin full of passengers and said, "You are not going to eat that!" "Of course", said the boy, "it is an 'old Lancashire tidbit." Whereupon the Captain rose and stormed out on deck. The boy finished his cracker with relish and got up to leave. No sooner had he stepped out on deck when the Captain took him by the lapels, pushed him up against a ventilator and threatened him with the ropes end if he was ever embarassed again. The boy told him that he was no longer under his command, whereupon the Captain said that whilst the Apprentice was still Indentured he was the reponsibility of the Captain. One could hardly believe that this was happening to a shipwreck survivor in the middle of the Atlantic and under threat of a U-boat attack at anytime. Needless to say he never saw that Gentleman again which was as well, as he would have refused to sail with him on any of the other Company's ships.

I know, because I was that Apprentice.

WRITTEN by: Alan Shard, F.N.I. West Vancouver B.C. CANADA |

|||||

After surviving the sinking of Putney

Hill, Alan returned to sea and served aboard the

MV Coombe Hill,

taking part in the supply convoys to

Algiers

and Bône,

North Africa, and then in the Italian Campaign to

Taranto and

Bari. Exciting events, but this time

without

loss.

He joined the Canadian Manning pool

in 1944 and was

appointed to the Canadian-built SS

Prince Albert Park where he served as

Second Mate until 1946.

Alan remained at sea until 1954

and from August 1951 until May 1952 he was Third Officer

aboard the CPR's SS Empress

of France, formerly the

Duchess of Bedford.

Alan also served as Chief Officer aboard the

DEV (Diesel-Electric Vessel)

Beaverbrae,

ex

Huascaran.

As well as being a Fellow of the Nautical Institute, Alan was

also a member of the Master Mariners of Canada.

Alan lived in West Vancouver, British Columbia, and

he spent his retirement years as an executive member

of the

Canadian Merchant Navy Veterans Association (CMNVA)

working

very hard on behalf of

Merchant Navy Veterans.

He was one of the contributors to

David O'Brien's splendid book

HX-72 First Convoy to Die:

The Wolfpack Attack that Woke Up the Admiralty

(Nimbus Pub. 1999).

Alan's story about the loss of the Putney Hill

is also part of

The Memory Project.

Alan Shard passed away at the age of 92 on May 11, 2015.

Many thanks to Tom Purnell for supplying the HTML used on this page. Tom Purnell's grandfather, Tom Purnell, was serving as Fourth Engineer aboard the MV Canonesa and lost his life when she was torpedoed by U-100 during the crossing of Convoy HX-72.

Alan's page is maintained by Maureen Venzi and is part of The Allied Merchant Navy at War website. |

May 17, 2000, Revised April 1, 2006, November 2, 2016

[Copyright reserved]