TO FRANCIS BACON

1923

Hail, Great Master! Prince of Nature’s lore!

We hang fresh bays about thy glorious Name,

And lift our voice, like faithful Ben of yore,

Thy goodness and thy merit to acclaim.--

Three hundred years ago thy powerful pen

Performed in silence that unrivalled deed,

Of marrying knowledge for the good of men

To eloquent Speech in a despised Weed.--

Though hapless victim of a cruel time,

Thine eyes looked tow rd a far-off rosy morn,

When, in a new world and a happier clime,

From tyrants freed, great nations would be born.--

Thy steadfast faith has won, thine heirs are we,

And now our hearts rejoice to honor Thee.

G. I. P.

3

THE BACON SOCIETY OF

AMERICA.

The Bacon Society of America was organized and held its first general meeting in New York City at the rooms of the National Arts Club on Monday, May 15th, 1922. Its announcement at that time says:

"In this age of marvelous progress in the knowledge of Nature’s laws and the consequent startlingly rapid succession of amazing discoveries and useful inventions, it seems most fitting that an association of scholars and laymen like this, recognizing the incalculable debt which mankind owes to the prodigious genius and indefatigable labors of the world’s greatest modern philosopher, FRANCIS BACON, should be permanently formed to study his life, works and influence."

"Bacon professed openly that he had taken all knowledge for his province, and would attempt, or at least begin the rebuilding of the Temple of Sciences from the bottom up. Ben Jonson, one of his literary helpers, has said in his Discoveries, "that he may be named and stand as the mark and acme of our language." The study of such vast activities must, therefore, necessarily embrace wide and varied fields. It must include also the lives and works of contemporaries and predecessors, both in England and in continental Europe, and indeed, for proper appreciation, a survey of the history of civilization. Bacon’s connection with the Shakespeare plays and poems, a matter for much needlessly heated and blind partisan controversy, has already been the subject of unprejudiced research by various members of the society. This will undoubtedly be continued in a more far-reaching and thorough way than heretofore pursued in some quarters.

"It should be also of particular concern to Americans to become better acquainted with Bacon’s part in the planting and promotion of the earliest British colonies in North America, because, though not generally known, he assisted in preparing the 1609 and 1612 charters of the Virginia company for the signature of King James I. of England, and, as a member of its council, always lent a friendly hand."

Full information about the officers, trustees and working committees of the Bacon Society of America, its constitution, and membership conditions will be found on the second page cover of this book.

4

FIRST MEETING OF THE

BACON SOCIETY OF

AMERICA

The first regular meeting of the Society for the season of 1922-1923 was held on the evening of November 20th, 1922, at the residence of Mr. and Mrs. A. Garfield Learned, 36 Gramercy Park, New York City. Over a hundred of the members and friends of the society were present, and a program of absorbing scholarly and social interest was offered, as follows:

Opening address by the President, Mr. Willard Parker. Printed on pp. 6 to 8.

Letter: "Greetings from the British Society to the American," from Mrs. Teresa Dexter, Hon. Secretary of the Bacon Society of Great Britain. Read by Mr. Parker. Printed on p. 8.

Paper: "Francis Bacon, the Founder of the New World," by the Hon. Sir John A. Cockburn, President of the Bacon Society of Great Britain. Read by Mr. Parker. Printed on pp. 8 to 10.

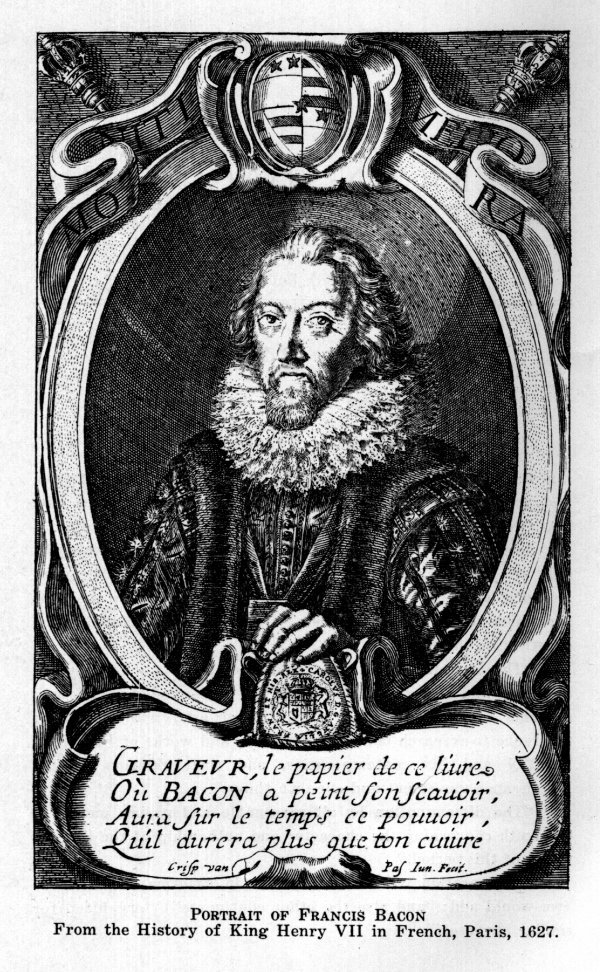

Paper: "Concealed Methods of Expression in English Literature," by Geo. J. Pfeiffer, Ph. D., Vice President. Read by the author, and illustrated with numerous lantern slides of original and facsimile title pages and text pages of old books, together with a fine portrait of Francis Bacon. This is probably the first time that actual specimens of cryptography, and its discussions have been thus presented from old books of the Elizabethan and Jacobean periods as evidence in public in this country. Printed on pp. 10-23; 24-32.

There followed an intermission with refreshments,--selections on the mandolin, wonderfully performed by Mr. Samuel Siegel,--and the adoption of an amendment to the constitution, providing for honorary membership and the election of the Hon. Sir John A. Cockburn as an honorary member.

Paper: "Francis Bacon and the Royal Society," by Dr. Geo. J. Pfeiffer. Read by Miss Adelaide Johnson. Printed on pp. 40 to 44.

Address by Dr. W. H. Prescott of Boston, Mass.

Paper: "Who Was Francis Bacon," by Mme. Amelie Deventer von Kunow, of Weimar, Germany. Read by Miss von Blomberg of Boston, Mass., who supplemented it with most interesting remarks. Printed on pp. 33 to 39.

5

OPENING ADDRESS

At the First Meeting of the Bacon Society of America by the

President, Mr. Willard Parker

Three hundred years ago Francis Bacon executed his last Will and Testament. He had lived and laboured for over sixty years, obsessed with the longing to do good to mankind and his people. Although thought by some to be the legitimate but unacknowledged heir to high estate, he fomented no rebellion to win it, but was content to see himself effaced, if only his country and his ideals might prosper thereby; and, when by such self-sacrifice, two great nations, after centuries of almost continuous yet fruitless struggles, were peacefully united, it was he, who, as head of the great committee to harmonize and amalgamate the laws of the two peoples, actually coined the name "Great Britain," which his land bears to this day.

In his Will and Testament, realizing that he had done for his country all that his position permitted, surrounded as he was by powerful enemies, he bequeathed his name and memory to Foreign Nations and the Next Ages; and now, three hundred years after, in a New World, a thousand leagues removed from the land of his birth, a Bacon Society has been organized to partake with gratitude in this priceless heritage.

There is no department of learning and letters but owes to Francis Bacon an inestimable debt. He contributed to Philosophy and Sciences, to History, Statesmanship and Law, and especially to Literature, creating a storehouse from which later generations have drawn more lavishly than from all his contemporaries combined. In the words of his friend and fellow-writer, Ben Jonson, "he may be named and stand as the mark and acme of our language," and it is "he who hath filled up all numbers, and performed that in our tongue which may be compared or preferred either to insolent Greece or haughty Rome," a very suggestive repetition of identically the same comparison Ben Jonson had already applied in 1623 to the plays of his beloved "The AVTHOR MR. WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE: and what he hath left us."

Because of the circumstances of his birth and his great philosophical and political aspirations, much of the product of his matchless pen had of necessity to be issued under the protecting veil of anonymity, pseudonymity and other safe-guards,--a very common practice in those days among the learned;--and as Bacon was familiar with many systems of cryptography, it

6

would be little short of miraculous, if he had not employed them as a vehicle for safely carrying his message to the next ages.

During Bacon’s life-time in England the envy of powerful enemies had kept him for many years on the side-lines, and finally led him to decide upon terminating his public career there. I speak advisedly when I say that it was his decision, and not theirs; for, after his so-called "fall," he was re-elected to the House of Lords, but declined to take his seat, believing that he could better serve mankind by dedicating the remaining years of his life to the preparation of his various literary works for transmission to posterity.

His philosophical writings were put into Latin, a dead and therefore stationary language, for he had seen the English tongue change under his hand and through his own compositions from the language of Chaucer to the language of Milton; and even his far-seeing astuteness could not realize how little improvement would be made upon his own literary performances in the next three centuries.

In recent times, however, Bacon Societies have at last been organized in England, France, Germany and Austria, for the purpose of studying and bringing to the knowledge of the world at large the true character and unprecedented abilities and labours of this master-mind. These societies and many individual students in Europe and America have done and published vast and valuable research work among original old records and books. Our American pioneers in particular have made noteworthy contributions, whose merits will undoubtedly receive increasing recognition; but there is still much left for this new Bacon Society of America to do, not only in encouraging research and publication of new information, but especially of disseminating the results so far attained among wider circles of readers.

There are thousands of open-minded truth-seeking Americans, who will welcome and support this useful educational work. It will be the endeavor and privilege of this society to enroll such sympathetic friends, and to publish its proceedings and other interesting matter from time to time in a periodical to be called "American Baconiana"; also to secure the publication and circulation of larger single works upon subjects related to its activities; to establish chapters in various American cities; and to co-operate with scholars and societies abroad in a spirit of mutual friendship and helpfulness. In evidence of this fellow-feeling there will be presented at this first meeting greetings from the Bacon Society of Great Britain, and a most able and instructive paper by its Honorable President, as well as a paper from the pen of a prominent literary woman of Germany.

7

Our membership extends already from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific, and this first gathering of over a hundred persons promises well for the future of our society and our good cause.

_________

LETTER OF GREETING

From the Bacon Society of Great Britain to the Bacon Society

of America

11 Hart Street, Bloomsbury, London, W. C.

Mr. Willard Parker,

President of the Bacon Society of America.

Dear Mr. Willard Parker:

This is to bring you the warmest greetings from the Bacon Society of England and good luck and prosperity for this your first publication.

We join hands with you across the sea in sending you an article by our president.

May the study of the Works of the Immortal Francis Bacon spread far and wide by your efforts, and give him honor to whom honor is due.

Yours very sincerely,

TERESA DEXTER,

Hon. Secretary of the Bacon Society of England.

_________

FRANCIS BACON

The Founder of the New World

(By the Hon. Sir John A. Cockburn, President of the Bacon Society of Great Britain)

The establishment of a Bacon Society in America marks an important epoch in the interpretation of history. There are Bacon Societies in England and on the Continent of Europe, but for several reasons there is no country where such a society could be more appropriately formed than in the United States. It would be difficult to over-estimate the debt which the world at large owes to the Author of the Great Instauration. He it was who provided the keys by which the secrets of nature were unlocked and the treasures of earth made available for the service of man. By his philosophy of usefulness, as contrasted with the barren disquisitions of scholasticism, the wheels of modern industry were set in motion. He was the father of invention and well has America profited by his precepts, for it is through the

8

facilities granted to inventive genius that the United States has attained her industrial greatness. Moreover, it should not be forgotten that it was Francis Bacon who advocated not only the fostering, but the protection of local industry, and denounced the policy of importing articles which could readily be produced at home.

But the claim of Francis Bacon to the gratitude of America has a still more substantial and special basis. The part played by him in founding the American Colonies has been hitherto overlooked. Until he took the helm in Transatlantic enterprise, all attempts to make a permanent settlement in Virginia had ended in disaster. It was after he became a prominent member of the Virginian Council, which included many of his most intimate friends, that success crowned its efforts. William Strachey, the first secretary of the Colony, dedicated his book on the "Historie of Traveile into Virginia Britannia" to Francis Bacon, and addressed him as "a most noble father of the Virginian Plantation." Strachey accompanied Sir Thomas Gates and Summers on the voyage to Virginia. The ship in which they sailed was wrecked on the shores of Bermudas, then known also as the island of devils. Their romantic adventures were chronicled by Strachey and were published by Purchas. Meantime, some of the episodes were worked into the Shakespeare play of the "Tempest," printed in the Folio of 1623.

In 1910, Newfoundland, when commemorating the tercentenary of its foundation, issued a postage stamp bearing the image of Francis Bacon, with the superscription "1610-1910, Lord Bacon, the guiding spirit in Colonisation Scheme." It may be remarked that the eastern fringe of the American Continent was at one time called the "New-found-land."

The Hon. James Beck, of the United States, in a recent speech in Gray’s Inn Hall, remarked that the two charters of government, which were the beginning of constitutionalism in America, and therefore the germ of the Constitution of the United States, were drawn up by Lord Bacon, and added that Bacon, "the immortal treasurer of Gray’s Inn," visioned the future and predicted the growth of America in the memorable words: "This Kingdom now first in His Majesty’s times hath gotten a lot or portion in the New World by the plantation of Virginia and the Summer Islands. And certainly it is with the Kingdoms of Earth as it is in the Kingdom of Heaven, sometimes a grain of mustard seed proves a great tree." "Truly," added Mr. Beck, "the mustard seed of Virginia did become a great tree in the American Commonwealth."

In the view of Bacon, the New World appeared as a pledge

9

of the dawn of a better age. He was constantly drawing a parallel between the inauguration of his philosophy and the passage through the formerly forbidding pillars of Hercules into the open ocean of discovery. These pillars were for centuries regarded by the circle-sailing seafarers of the Mediterranean as the limits of enterprise. Bacon chafed against the restrictions to enquiry imposed by the schoolmen. In the preface to the Great Instauration he says that "Sciences also have, as it were, their fatal columns." "Why," he remarks, "should we erect unto ourselves some few authors to stand like Hercules’ Columns beyond which there should be no discovery of knowledge." The frontispiece to the "Advancement of Learning" represents a ship in full sail triumphantly passing through those barriers.

It is surely high time for the Republic of Republics to exalt the name of the greatest of its protagonists; and the president and promoters of the Bacon Society of America are to be congratulated on taking the initiative.

Hepworth Dixon lamented the oblivion into which the name of Francis Bacon as a founder of the United States had been permitted to fall. He looked forward to the day when "the people of the Great Republic would give the great and august name of Bacon to one of their splendid cities." In the light of new knowledge, they might well do even more than this. If the United States were to erect to the memory of Francis Bacon, Lord Verulam, Viscount St. Alban, a twin statue, as noble and impressive as that of "Liberty," which stands now at the portal of their ocean gateway, it would be no more than a just tribute to one to whom they owe so much, and whom the intelligence of the world delights to honour.

JOHN A. COCKBURN.

_________

CONCEALED METHODS OF

EXPRESSION IN ENGLISH

LITERATURE

(By Geo. J. Pfeiffer, Ph. D.)

Few people, even among those well read, are aware of the very extensive use made by many authors of methods of expression more or less concealed by artificial means. This practice may be traced back into remote antiquity among all the more civilized nations, and must be reckoned with as an important factor in their intellectual development. It arose from a variety

10

of causes and motives; for example, desire for exclusive control of valuable knowledge, self-protection in free thought and statement against repressive despotism of one kind or another, or against the opposition of ignorance and selfish interests with their attendant ills. Our wise Shakespeare with his usual accuracy and grace of speech unburdens his heart through the sententious Jaques about this unhappy state of affairs thus: "Giue me leaue to speak my minde, and I will through and through cleanse the foule bodie of th’ infected world, if they will patiently receiue my medicine."* By skillful artifice, too, could the shafts of satire be securely shot; the identity of anonymous and pseudonymous authorship revealed without risk of dangerous notoriety, and a graceful compliment offered to powerful patron or friend.

During the Renaissance period in Europe the symbolic, allegorical, veiled, mystical, and other more or less involved and indirect styles of literary composition attained extraordinary favor. A veritable mania for mystification possessed the learned world in the fifteenth, sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, so effectively excluding the uninitiated or merely unlearned outsiders, that, with ensuing political, philosophical and religious revolutions, the knowledge of such enigmatical methods of expression, as they are also sometimes called, has been largely lost. In consequence, much of the true thoughts and feelings, as well as historic information put into those writings, has been overlooked or misunderstood, so that such facts are in our present state of mind difficult to realize and recover.

It will surprise any one not familiar with the matters thus but briefly referred to, to learn what a modern specialist is moved to say on this subject, the bibliophile Monsieur Fernand Drujon, who published in 1888 at Paris his important work on Books Requiring Keys, "Les Livres à Clef." We read in his preface: (translated)

"Every book containing real facts, or allusions to real facts, dissimulated

under enigmatic veils, more or less transparent,--every book introducing

real personages, or making allusion to real personages under feigned or

altered names,--is a book requiring a key," (unlivre à clef).

"The Key of a book of this nature is nothing else than the explanation of

the enigmatic characters, or of the feigned names which it contains."

"There is much to say about the infinite diversity of works comprising the

category of books with keys,--about the various motives which inspired

their authors,--about the

__________

* Note--This quotation is in the spelling of the first Shakespeare folio, for we believe that the actual spelling of any old edition quoted should be followed, as closely as possible.

11

artifices more or less ingenious, which they employed to disguise liberal or

censurable ideas, beneficial or malicious thoughts."

The learned author points out some of the devices used, suggests the chief motive for them, and mentions some published and unpublished works, with explanations. He says in another place:

"It is also very certain that divers works to which I have been able to

devote only a few lines, belong into the category of books with keys; such are, for

example, the works of Swedenborg, for which the "hieroglyphic key" has been

made,--the "Comèdie Humaine" of Balzac,--the majority of the works of the

Marquis de Sada,--the works of the poet Spenser"; (note that!) etc., etc.,--"but

each of these keys, if ever they can be made, will require years of labour, and the

collective efforts of several erudite men."

The author enumerates many other works, among them: Satyro--Mastix (1602) by Thomas Dekker,--The Poetaster (1601) by Ben Jonson,--the Argenis (1630) of John Barclay, with key,--the Satyricon (1637) of John Barclay, with key,--Macarise, ou La Reine des Isles Fortunèes (1664) by François Hedelin,--Albion and Albanius, an opera (1685) by John Dryden,--The Hind and the Panther (1687) by the same,--Les Caractères (1688) of La Bruyére,--Gulliver’s Travels (1726) by Jonathan Swift,--Adventures of Roderick Random (1748) by Tobias Smollett,--A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy (1768), and Tristram Shandy (1715-1768) by Laurence Sterne,--the Works of Rabelais (Gargantua, being Francis I., and Pantagruel, Henri II.),--the Works of Cyrano de Bergerac,--the Works of Moliere,--the Works of Voltaire,--the Works of Jean Jacques Rousseau,--Nouma Roumestan, and Fromont jeune et Risler ainé, both by the modern French author Alphonse Daudet.

He might have added many more, including the works of the Troubadours and true Alchemists, the Rosicrucians, Francis Bacon, William Shakespeare, Robert Burton, Ben Jonson, William Camden, Izaak Walton, Daniel Defoe,--of a host of Italians, including Dante Alighieri, Petrarch and Boccaccio,--of the Frenchman, Blaise de Vigenère (especially "Les Images ou tableaux de platte peinture des deux Philostrates sophistes grecs," etc., 1637),--of the Germans "Gustavus Selenus" (pseudonym of the versatile Henry Julius, Duke of Brunswick, and brother-in-law to King James I. of England,--his Cryptomenitices et Cryptographiae, 1624), and Goethe, Schiller, Heine, Novalis, etc.

To study old authors from modernized reprints, in which the text and appearance of the original or early printed pages has

12

been for whatever reason changed, is fundamentally wrong, and no doubt accounts for the strange fact that the solution of many important literary problems has not yet been achieved.

Any alteration of an original text, no matter how good the intention, destroys its value for first-hand scientific study; an author’s veiled or concealed meaning, or some subtle hint or typographical proof of it, may thus be utterly lost, and his very aim and art destroyed. It is a kind of sacrilege, nothing less,--a falsification of the truth.

The scholarly Isaac Disraeli, father of the more famous Earl of Beaconsfield, on the other hand, points out the advantages of revision by authors themselves, and the particular value of first editions, in his "Curiosities of Literature" (Vol. 1., articles: The Bibliomania and Errata)

"There is an advantage," he says, "in comparing the first with subsequent

editions; for among other things, we feel great satisfaction in tracing the variations

of a work, when a man of genius has revised it. There are also other secrets well

known to the intelligent curious, who are versed in affairs relating to books. Many

first editions are not to be purchased for the treble value of later ones. Let no lover

of books be too hastily censured for his passion, which, if he indulges with

judgment, is useful."

As an illustration he speaks amusingly of Errata, the errors in the letter-press of a book, often assembled and corrected in a little table at its end.

"Besides the ordinary errata, which happen in printing a work, others have

been purposely committed that the errata may contain what is not permitted to

appear in the body of the work. Wherever the inquisition had any power,

particularly in Rome, it was not allowed to employ the word fatum, or fata" (that

is: fate or the Fates,--Ed.) "in any book. An author, desirous of using the latter

word, adroitly invented this scheme: he had printed in his book facta" (that is:

deeds or acts,--Ed.) "and in the Errata he put, ‘for facta, read fata.’"

Many other curious and amusing examples are cited; among them this:

"At the close of a silly book, the author as usual printed the word FINIS.--

A wit put this among the errata with this pointed couplet:

‘FINIS!--An error, or a lye, my friend!

In writing foolish books--there is no end!’"

Even Rare Ben Jonson has a few words on this subject in his Discoveries:

"But some will say, Criticks are a kind of Tinkers; that make more faults,

then they mend ordinarily." . . . "It is true, many bodies are the worse for

meddling with: And the multitude of Physicians hath destroyed many sound

Patients, with their wrong practise. But the office of a true

13

Critick, or Censor, is, not to throw by a letter any where, or damne an innocent

Syllabe, but lay the words together, and amend them; judge sincerely of the

Author, and his matter, which is the signe of solid, and perfect learning in a man."

The necessity to use unadulterated texts for serious literary study will be conceded; but the actual existence and use in books of any secret methods of expression might still be doubted, and even denied. To prove, therefore, the knowledge and use of such methods in the older literature of England by original examples or quotations from the authors themselves is my next aim, and I will call for my first witness the renowned Englishman of the thirteenth century, ROGER BACON, the Franciscan friar, who was known as the Doctor Admirabilis, studied at Oxford and Paris, and was deeply learned in languages, alchemy, optics, and many other sciences, including secret writing.

He has been designated by H. G. Wells one of the greatest men in history, and at this very time special interest in him has been revived by the recent transfer to this country of one of his manuscript works, the property of Mr. Wilfrid M. Voynich. This thirteenth century literary treasure seems to be written in most intricate ciphers, which are now being decoded by Professors William R. Newbold and C. E. McClurg of the University of Pennsylvania; and its discovery has a further value on account of what Roger Bacon has to say about methods of secret writing in his Latin treatise on "The Admirable Power and Art of Nature." This is contained in a larger work, translated into English, and published at London in 1597, under the title "The Myrror of Alchemy." The following extracts are taken, however, from Ethan Allen Hitchcock’s remarkable book on "Swedenborg, a Hermetic Philosopher" (New York, 1858; pp. 198-202):

"It is reputed a great folly to give an ass lettuce, when thistles will serve his turn; and he impaireth the majesty of things who divulgeth mysteries. And they are no longer to be termed secrets, when the multitude is acquainted with them." . . . .

"Now, the cause of this concealment among all wise men, is, the contempt and neglect of the secrets of wisdom by the vulgar sort, who know not how to use those things which are most excellent" . . . . "He is worse than mad that publisheth any secret, unless (by mystical writing, is meant) he conceal it from the multitude, and in such wise deliver it, that even the studious and learned shall hardly understand it."

"This hath been the course which wise men have observed from the beginning, who by many means have hidden the secrets of wisdom from the common people."

"Some have used characters and verses, and divers others riddles and figurative speeches."

"And an infinite number of things are found in many books

14

and sciences obscured with such dark speeches, that no man can understand them without a teacher."

"Thirdly, some have hidden their secrets by their modes of writing; as, namely, by using consonants only: so that no man can read them, unless he knows the signification of the words:--and this was usual among the Jews, Chaldaeans, Syrians, and Arabians, yea, and the Grecians too: and therefore, there is a great concealing with them, but especially with the Jews;". . . . . .

"Fourthly, things are obscured by the admixture of letters of divers kinds; and thus hath Ethicus the Astronomer concealed his wisdom, writing the same with Hebrew, Greek and Latin letters, all in a row."

"Fifthly, they hide their secrets, writing them with other letters than are used in their country," and so forth.

He concludes this most instructive passage by saying:

"I deemed it necessary to touch these tricks of obscurity, because haply myself may be constrained, through the greatness of the secrets which I shall handle, to use some of them, so that, at the least, I might help thee to my power."

No wonder that the deeply studious Hitchcock, who became later a Civil War general in the Federal Army, and was endowed with an unusually clear unbiassed mind, should exclaim with astonishment, upon discovering these highly significant words of Roger Bacon: "he has taken such especial pains to prepare his reader for his mystical writing, that it seems wonderful how the subject at least of his treatise should have escaped observation, as it appears to have done."

Roger Bacon was an Alchemist, and all true alchemists practised similar secret, and deliberately obscured or concealed methods of writing. They were the pioneers of natural philosophy in the prevailing darkness of the Middle Ages; they lived a more or less retired life, working in mysterious laboratories, no doubt with occasional explosions and other terrifying results; they wrote in a most fantastic jargon. All these things in those ignorant and superstitious times brought them into disrepute with the common people as necromancers and magicians in league with the devil, and exposed them to dangerous persecution. There were, of course, also imposters and swindlers among them, who exploited popular credulity and greed by claiming ability to make gold out of base metal, for a consideration; but the genuine alchemists were in reality advanced thinkers and reformers with a decidedly ethical or religious aim.

"The salvation of man," says Hitchcock in his "Alchemy and the Alchemists," "his transformation from evil to good, from a state of nature to a state of grace, was symbolized under the figure of the transmutation of metals. The writings of the alchemists are all symbolical; and under the words, gold, silver, sol, luna, wine, and a thousand other words and expressions, in-

15

finitely varied, may be found their opinions upon the great questions of God, Nature and Man. Their literal sense is often no sense at all." (The best proof in itself that their writings were not meant to be literally understood, any more than the fables, mythologies and religions of the ancient world. In all such cases the Real in Nature and Life must be looked for under the symbols, which, if true, can then be translated into plain rational speech). "The most abundant warnings are given in the writings of the alchemists not to understand them literally. ‘Let the studious reader,’ says one, ‘have a care of the manifold significations of words, for by deceitful windings, and doubtful, yea, contrary speeches (as it would seem) philosophers unfold their mysteries, with a desire of concealing or hiding the truth from the unworthy, not of sophisticating, or destroying it.’"

Their particular methods of writing and teaching have one distinct merit: the student is compelled to labor and think for himself in order that by such self-improvement he may learn; he must seek to find, and is then often rewarded by the keen pleasure of first-hand discovery. I recall a personal experience which may serve for illustration:

One day, years ago, when, as an assistant in chemistry at Harvard University, I was browsing in its rich library, I pulled out from a row of antique brown leather backs a little volume on Alchemy. Its title-page bore the inscription (in part):

"CHYMICAL COLLECTIONS AND HERMETIC SECRETS, Translated by IAMES HASOLLE Qui est Mercuriophilus Anglicus" (who is the English lover of Mercury).

It was printed at London in 1650, and was composed in that mysterious jargon, which no doubt means a lot of things to the author, but very little to a novice like me. The author himself I had never heard of before, and wondered who he might be. Soon after, continuing my examination of old alchemical books, I came upon a much more comprehensible one, which proved of absorbing interest, and of which I have since acquired an excellent copy. It had the strange title:

"THEATRUM CHEMICUM BRITANNICUM,"

was written or put together

"By ELIAS ASHMOLE Qui est Mercuriophilus Anglicus," and printed at London in 1652.

This Ashmole, according to the cyclopedias, was the greatest "virtuoso and curioso" of his day, a lawyer by profession, later a student at Oxford, dabbling in Astrology and Alchemy, a noted antiquarian, and founder in 1682 of the famous Ashmolean Museum, housed in a building erected by Christopher Wren.

16

It struck me that Ashmole called himself in this book, which is a collection of various alchemical writings with introduction and annotations by himself, "Mercuriophilus Anglicus," like that other writer Iames Hasolle. And it suddenly occurred to me, too, that this epithet, applied thus to both names, might be intended to convey to the reader, that they referred to the same ELIAS ASHMOLE. A certain similarity between the letters making up these two names finally suggested that the letters of Elias Ashmole’s name were perhaps merely transposed to produce the other name; and a test shows this to be fact. I had in brief identified the unknown author Iames Hasolle; but later on I found this anagrammatic pseudonym of Elias Ashmole already noted in Drujon’s "Livres à clef" (Books requiring keys) mentioned above.

The first piece printed in Ashmole’s Chemical Theatre is "The Ordinall of Alchemy, written by Thomas Norton of Bristoll," begun, according to that author’s own statement, in 1499; and Ashmole’s first remarks in the annotations (p. 437) refer to it. The first line of the proem in that long metrical composition, and the first line each of the following seven chapters read thus:

|

p. |

6. |

TO the honor of God, One in Persons Three, |

|

p. |

13. |

MAIStryeful marveylous and Archimastrye |

|

p. |

23. |

NORmandy nurished a Monke of late, |

|

p. |

39. |

TONsile was a labourer in the fire |

|

p. |

45. |

OF the grosse Warke now I will not spare, |

|

p. |

52. |

BRISE by Surname when the chaunge of Coyne was had, |

|

p. |

92. |

TOwards the Matters of Concordance, |

|

p. |

103. |

A parfet Master ye maie him call trowe" (the word "call" is redundant, but perhaps intended) |

and Ashmole says:

"Pag. 6. 1 in. 1 TO the honor of God-------

FRom the first word of this Proeme, and the Initiall letters of the six following chapters (discovered by Acromonosyllabiques and Sillabique Acrostiques) we may collect the Author’s Name and place of Residence: For those letters, (together with the first line of the seventh Chapter) speak thus,

Tomas Norton of Briseto,

A parfet Master ye maie him call trowe.

Such like Francies were the results of the wisdome and humility of the Auncient Philosophers, (who when they intended not an absolute concealment of Persons, Names, Misteries, &c.) were wont to hide them by transpositions" (He might have added, ‘like myself,’--Ed.) "Acrostiques, Isogrammatiques, Symphoniaques, and the lyke (which the searching Sons of Arte might possibly unridle, but) with designe to continue them to others, as concealed things."

17

The fantastic names here used belong to various artificial letter-devices.

At the end of the proem or introduction to this piece Norton invokes the dread of God’s curse to prevent any tinkering with his text.

"Now Soveraigne Lord God me guide and speede,

For to my Matters as now I will proceede,

Praying all men which this Boke shall finde,

With devoute Prayers to have my soule in minde;

And that noe Man for better ne for worse,

Chaunge my writing for drede of Gods curse:

For where quick sentence shall seame not to be

Ther may wise men finde selcouthe previtye;

And chaunging of some one sillable

May make this Boke unprofitable.

Therefore trust not to one Reading or twaine,

But twenty tymes it would be over sayne;

For it conteyneth full ponderous sentence,

Albeit that it faute forme of Eloquence;

But the best thing that ye doe shall,

Is to reade many Bokes, and than this withall."

Besides the alchemists, there were other classes or writers in that age, who were well versed in secret or veiled methods of expression, and among them notably the poets. Chaucer, Gower, Leland and others are named as early ones quite familiar with alchemic lore; witness, for example, Chaucer’s "Tale of the Chanons Yeoman," reprinted in full by Ashmole with useful annotations.

A fascinating little work to consider in the study of veiled or concealed writing is The Shepheardes Calender, published anonymously in 1579, and later included in the works of Edmund Spenser; and once more there are plain indications given of concealed things. In the prefatory Epistle of this collection of twelve poetical pieces written in the pastoral style, we read:

"Now as touching the generall dryft and purpose of his AEglogues, I mind not to say much, him selfe labouring to conceale it."

But this cannot be seriously meant; for, of course, if real concealment had been intended, nothing would certainly have been said about it. On the contrary, ’t is merely a device of the clever author to excite the reader’s curiosity, and induce him to look for interesting matter, which does not appear on the surface; for which purpose, indeed, the necessary help is immediately offered.

"Hereunto Haue I added," says the writer of the Epistle,

18

(possibly the author himself, playing hide-and-seek), "a certain

Gloss or scholion for thexposition of old wordes & harder phrases: for somuch as I knew many excellent & proper deuises both in wordes and matter vvould passe in the speedy course of reading, either as unknovven, or as not marked, and that in this kind, as in other vve might be equal to the learned of other nations, I thought good to take the paines vpon me, the rather for that by means of some familiar acquaintaunce I vvas made priuie to his counsell and secret meaning in them . . . ."

We have then to finde our way in this book once more through a deliberate maze of mystification, and that is why Drujon said that the works of Spenser require a key.

Each of the twelve poems has a gloss, and a most casual examination of these glosses reveals hidden or veiled matter in abundance; and often all disguise is then dropt, as in the following case.

The October eclogue contains the lines:

"Abandon then the base and viler clowne,

Lyft by thy selfe out of the lowly dust:

And sing of bloody Mars, of wars, and giusts,

Turn thee to those that weld the awful crowne,

To doubted Knights, whose woundlesse armour rusts,

And helmes unbruzed waxen dayly browne.

There may thy Muse display her fluttryng wing,

And stretch her selfe at large from East to West:

Whither thou list in fayre Elisa rest,

Or if thee please in bigger notes to sing,

Aduaunce the worthy whome shee loueth best,

That first the white beare to the stake did bring."

Elisa is, of course, Queen Elizabeth; and her best loved worthy? Well, he is cautiously "guessed at" in the gloss.

"He meaneth (as I guess)," says our trusty guide, "the most honorable and renowned the Erle of Leycester, who by his cognisance" (that is, the white bear brought to the stake,--Ed.) "(although the same be also proper to other) rather then by his name he bewrayeth," (that is, reveals), "being not likely, that the names of noble princes be knovvn to country clovvne."

The guarded allusion to the Queen’s apparently well-known relations with Leicester is highly instructive. It was too dangerous a subject for quite open speech, but well adapted for subtle compliment to both.

In the January gloss we are informed first that

"COLIN Cloute) is a name not greatly vsed," . . . "Vnder

19

which name this Poete secretly shadoweth" (that is, conceals,--Ed.) "himself, as sometime did Virgil vnder the name of Tityrus."

Further down we find that

"Hobbinol)" (another personage mentioned in the January eclogue,--Ed.) "is a feigned country name, whereby, it being so commune and vsvall seemeth to be hidden the person of some his very speciall & most familiar freend, whom he entirely and extraordinarily beloued". . . . .

We read finally at the bottom of the same page:

"Rosalinde) is also a feigned name, vvhich being wel ordered, vvil bevvray" (that is, reveal,--Ed.) "the very name of hys loue and mistress vvhom by that name he coloureth" . . (that is, represents or disguises,--Ed.)

Now, to well order that name Rosalinde, in order to discover what lady the poet actually had in mind, can mean only one thing; namely, to re-arrange or transpose the letters making it up in the proper way, whatever that might be. This would give no special difficulty, however, to the class of readers for whom The Shepheardes Calender was written, for the lady’s identity was an open secret for them. She has always had, and still has a host of passionate admirers, and has been sung by many poets under many names. Modern ones alike feel her immortal charm, as the following little piece may testify:

TO ROSELINDA

Rose and Lily, Sun and Dove,

I loved them all in dreams of Love;

But, since I have known Thee, Thou art,

O Rosalinde, the Queen of my heart.

Our Shake-speare, infinitely more learned than commonly believed, was, of course, also well aware of the secret, and has playfully alluded to it. Listen to the words of the enraptured lover Orlando, pinning sonnets to his Rosalinde on the trees of the imaginary Forest of Arden.

"Hang there my verse, in witnesse of my loue,

And thou thrice crowned Queene of night suruey

With thy chaste eye, from thy pale sphere aboue

Thy Huntresse name, that my full life doth sway.

O Rosalind, these trees shall be my Bookes,

And in their barkes my thoughts Ile charracter,

That euerie eye, which in this Forrest lookes,

Shall see thy vertue witnest euery where.

Run, run Orlando, carue on euery Tree,

The faire, the chaste, and vnexpressiue shee."

20

Where is that "Huntress name," that his full life doth sway? But thereby hangs a pleasant tale for another day.

A vast number of books were written in the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries about what I have called Concealed Methods of Expression; but that designation is not wholly correct, because a complete concealment, which is quite easy to effect, could never be found out. We are discussing rather methods for the partial concealment or disguising of an author’s purpose, so that his meaning may not be immediately obvious. A reader’s interest and curiosity are thus aroused, and if he have a favorable and ingenious mind, he will learn to observe and think for himself; he will derive peculiar pleasure from the free exercise of his wits, and profit greatly by the skill and knowledge thus gained from books of this class.

It is to be expected that "Some of the sowre sort will say it is nothing but a troublous joy, and because they cannot attaine to it, will condemne it, least by commending it, they should discommend themselues. Others more milde, will grant it to bee a dainty deuise and disport of wit not without pleasure;"

These remarks applying well to our subject, though made more particularly about playing with anagrams, occur in William Camden’s famous little collection of miscellanies entitled "REMAINES CONCERNING BRITAINE," (edition of 1623). William Camden, known as Learned Camden, was a great historian and antiquary, a friend and associate of Francis Bacon. It was he, who started Ben Jonson, a bricklayer’s son, upon his literary career, and all he says deserves respect. We find him well informed and skilled in many of the literary tricks we are studying,--such as Anagrams, or Transpositions, Rebus, or Name-devices, Impreses or Heraldic Emblems and Mottoes. And why? Because he appears to have found them a delightful witty relaxation after serious work, and, as a man with grave official responsibilities, perhaps also helpful in other ways. His chapter on Anagrams is especially valuable, because he gives the rules for their construction, and numerous examples. It opens thus:

"THE onely Quint-essense that hitherto the Alchimy of wit" (An interesting reference to the intellectual nature of true Alchemy,--Ed.) "could draw out of names, is Anagrammatisme, or Metagrammatisme, which is a dissolution of a name truely written into his Letters, as his Elements, and a new connexion of it, by artificiall transposition, without addition, subtraction, or change of any letter, into different words,--making some perfect sense applyable to the person named."

"The precise in this pratise strictly obseruing all the

21

parts of the definition, are onely bold with H, either in omitting or retaining it, for that it cannot challenge the right of a letter. But the licentiats somewhat licentiously, lest they should preiudice poeticall liberty, will pardon themselues for doubling or reiecting a letter, if the sence fall aptly, and thinke it no iniury to vse E for AE, V for W, S for Z, and C for K, and contrariwise."

"The French exceedingly admire and celebrate this faculty for the deepe and farre fetched antiquity, the piked fines and the mysticall significations thereby;". . . . . .

The chapter on Anagrams ends in the 1623 edition on p. 157, and this will be particularly discussed in some future paper. We will point out here only that a Mr. Tash "a special man in this faculty," is credited there with an anagram upon Sir Francis Bacon, and that immediately after is mentioned Mr. Hugh Holland, "peerelesse in this mystery." It is remarkable that this peerless master of mystification by artificial letter-devices was honored with a place among the eulogists at the head of the great Shakespeare folio of the same year as this book, 1623; his poem is entitled:

"Vpon the Lines and Life of the Famous

Scenicke Poet, Master WILLIAM

SHAKESPEARE."

It is not unreasonable, therefore, to suppose that this little composition may be a worthy specimen of his matchless skill, and it should certainly be examined with care in this respect. (See W. S. Booth, "Some Acrostic Signatures of Francis Bacon," Boston, 1909, p. 331).

On the same page 157 begins the chapter on Armories ("or Armes"), very appropriately described as "silent names." They also are a means of veiled expression, as we have already seen above in our quotation from the October eclogue of The Shepheardes Calender, where Leicester is referred to without mention of his name, but by his "cognizance," as the gloss-writer put it.

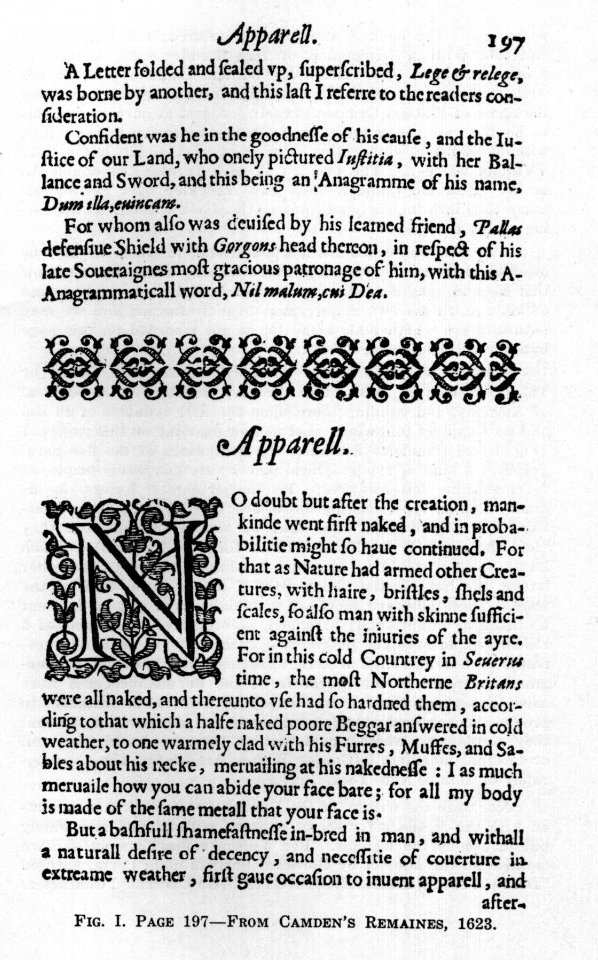

Page 197 (Fig. I.) of Camden’s Remaines (1623) is of unusual interest for our present purpose. Its upper half bears the end of the chapter on IMPRESES, or heraldic emblems, and their mottoes. Its two last paragraphs contain Latin mottoes, stated to be anagrams, namely, "Dum illa, euincam" and "Nil malum, cui Dea." It remains only to discover what name they stand for, and this the present writer succeeded in doing some

22

23

years ago. The book is anonymously printed; but Ben Jonson had told William Drummond of Hawthornden upon a visit to Scotland, that it was written by William Camden; and so the writer ventured the guess, that perhaps these anagrams concealed the name of William Camden himself. A test at once proved this to be the case, each Latin motto being perfectly transposable, without addition, subtraction or change of a single letter, into VVilliam Camden. The two u’s in each furnish the double U, or W. How old Camden must have chuckled over getting his name thus into the early editions of this book without its appearance on the title-page!

And who was Camden’s learned friend, to whom he says he owed these devices? He doesn’t mention any name, but we know that he had such a friend and patron in the most learned man of his age, in his own countryman Francis Bacon; and we may naturally ask whether his name too is not recorded on this page by some artificial letter-device.

Mention was made above of a syllabic acrostic placed by Thomas Norton of Bristol into the very structure of his Ordinal of Alchemy, and running there upon the first syllables of Proem and six Chapters following. Let us now examine on this page 197 (Fig. I.) of Camden’s Remaines the beginnings of the five paragraphs,--a kind of typographical places very commonly employed for informing letter-devices. The initial capital letters, in ordinary Roman type, reading down, are: A C F O B, and a practised eye perceives at once that by simple transposition they yield the name F BACO, the Latin form of F BACON, which latter, indeed, would be obtained by simply adding to the other letters the large initial N in the lower half of the page. These observed facts are undeniable, and will or may not be taken as intentionally arranged, according to the extent of a reader’s experience and judgment in such matters. Such arrangements of letters, called acrostic anagrams, are, however, of common occurrence in the literature of the Renaissance, and were used throughout the Divine Comedy by Dante, for instance, to produce names, and elucidate passages and allusions in the text they accompany, which would without them not yield their full or internal meaning. (Confer Walter Arensberg, The Cryptography of Dante, New York, 1921.)

Nor were the writers of the English Renaissance unacquainted with the methods for secret expression developed and widely put in use by the Italians. Ben Jonson refers to a well-known treatise on this subject by Giovanni Battista della Porta, entitled "DE FURTIVIS LITERARUM NOTIS" (On Concealed Characters

24

in Writing), published at Naples in 1563, and also later at Strasburg in a French translation (Les Notes Occultes des Lettres) in 1606. Ben’s epigram No. XCII, "The New Cry," satirizing young up-start statesmen, contains the following lines:

"They all get Porta, for the sundry wayes

To write in cypher, and the severall keyes,

To ope’ the character. They ’have found the sleight

With juyce of limons, onions" (dash) "to write,

To breake up seales, and close ’hem. And they know,

If the States make peace, how it will go

With England. All forbidden books they get,

And of the poulder-pot, they will talke yet."

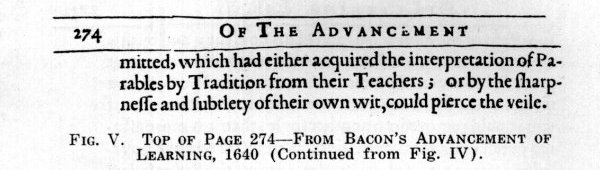

The great Francis Bacon himself, Jonson’s patron and employer, whom he named as the mark and acme of our language, whose genius was without a peer in recorded history, and who devoted a large part of the sixth book of his "Proficience and Advancement of Learning" (Oxford, 1640) to the arts of expression, did not for good reason omit reference to private or secret methods of uttering one’s mind, including ciphers. He treats of all these in a masterly way, devoting much attention to a famous method of ciphering, which he says: "in truth, we devised in our youth, when we were at Paris: and is a thing that yet seemeth to us not worthy to be lost. It containeth the highest degree of Cypher which is to signifie omnia per omnia," meaning that there is no restriction whatsoever in applying its principle to any kind of matter and any kind of means for safely and secretly conveying it. He mentions also "the knowledge of Discyphering, or of Discreting Cyphers, though a man were utterly ignorant of the Alphabet of the Cypher," and as if to meet the objection that he was passing over these important things too slightingly, remarks significantly: "Neither have we (in our opinion) touched these Arts perfunctorily, though cursorily; but with a piercing stile extracted the marrow and pith of them out of a masse of matter. The judgment hereof we referre to those who are most able to judge of these Arts." (p. 270).

Francis Bacon, like his great predecessor Roger Bacon three hundred years earlier, was familiar with many concealed methods of expression, but unlike him does not seem to have openly stated anywhere that he might use them in his own works. That would have been folly, in an unenlightened age and with his constant exposure to the intrigues and spies of unscrupulous political competitors and personal enemies. But there are abundant proofs, that he did make every allowance in composing and publishing his writings for just such conditions, which no doubt com-

25

pelled him to develop special private means for comparatively free speech and safe intercourse with kindred spirits. We must therefore be prepared to find Bacon and his confidential associates and literary helpers using all manner of extraordinary and even unheard-of devices, the very originality of these securing the protection so much needed for baffling suspicious opponents.

For illustrating Francis Bacon’s caution and circumspection in issuing his works an excellent example is fortunately available, discovered by the writer some years ago, and this will at the same time demonstrate Bacon’s ability to impart direct information by indirect means, and prove that he used concealed methods for delivering knowledge.

His faithful chaplain William Rawley, who describes himself (Resuscitatio, 1657, Epistle to the Reader) as "Having been employed, as an Amanuensis, or dayly instrument, to this Honourable Author; And acquainted with his Lordships Conceits, in the composing, of his Works, for many years together; Especially, in his writing Time;". . . .says in the Life of his master, written by himself for that book:

"I have been enduced to think; That if there were, a Beame of Knowledge, derived from God, upon any Man, in these Modern Times, it was upon Him. For though he was a great Reader of Books; yet he had not his Knowledge from Books; But from some Grounds, and Notions, from within Himself. Which, notwithstanding, he vented, with great Caution, and Circumspection. His Book, of Instauratio Magna, (which, in his own Account, was the chiefest, of his works,) was no Slight Imagination, or Fancy, of his Brain; But a Setled, and Concocted, Notion; The Production, of many years, Labour, and Travell. I my Self, have seen, at the least, Twelve Coppies, of the Instauration; Revised, year by year, one after another; And every year altred, and amended, in the Frame thereof; Till, at last, it came to that Modell, in which it was committed to the Presse:". . .

It is clear that Bacon spent very special effort upon the perfection of this great philosophical work of his, of which the first part "DE DIGNITATE ET AUGMENTIS SCIENTIARUM, Libri IX," was finally published in 1623. (The same year, by the way, as the first Shakespeare folio of plays). This noble volume contains very little prefatory matter,--only an Epistle, and a table of contents for Books II-IX, called Partitiones Scientiarum. Seventeen years after, in 1640, appeared at Oxford an English version of this work, printed by the university printer Leonard Lichfield; but this great book was given many pages of prefatory matter never published before, and of peculiar value. One particular page of it (Fig. II.) is of special interest for the subject we are discussing, and one can gather from it also an idea of the

26

FIG. II. TABLE--FROM BACON’S ADVANCEMENT OF LEARNING, 1640.

27

extraordinary methodical way in which Bacon planned and executed his literary work.

The title of this page reads:

"The Emanation of SCIENCES, from the Intellectuale Faculties of MEMORY IMAGINATION REASON."

From Memory emanates HISTORY, from Imagination POESY, and from Reason

PHILOSOPHY;--and we must not fail to note in passing that the supposedly legal-minded, coldly dissecting Thinker Bacon names Poesy as a great branch of learning. After a profound consideration of its various kinds in the closing chapter XIII of Book II, he refers to it once more with delightfully eloquent words in the opening paragraph of Book III.

"ALL History (Excellent KING) treads upon the Earth, and performes the office of a Guide, rather than of a light; and Poesy is, as it were a Dream of Knowledge; a sweet pleasing thing, full of variations; and would be thought to be somewhat inspired with Divine Rapture; which Dreams likewise pretend: but now it is time for me to awake, and to raise my selfe from the Earth, cutting the liquid Aire of Philosophy, and Sciences."

But to return to our task from such dry legal terms! The three sciences mentioned as emanations are elaborately subdivided on the page here reproduced, and referred to the several books handling them in this volume, noted in order down the right margin. But in scanning these numbers from the top down as follows: LIB. II III IV V VI VII VIII IX, and LIB. I,--one observes with a start,--comes at the bottom! Yet in the text proper it precedes the others, as is natural. This change of order in the table is, however, not an error, but introduced with clear intent, as the statement of the subject-matter of book I shows. It reads:

"The Preparation to these Books, is populare, not Acroamatique: Relates the Prerogatives & Derrgations of Learning. LIB. I. (Some copies have instead of "Preparation" the word "Apparatus," which also has that meaning.)

The little word "not" is printed in italics, to lend emphasis to the important information here given, that the contents of Book I, which serves merely as an introduction to the other books, are popular in nature,--I repeat "not Acroamatique"; so that we are forced to conclude from this strong negative, that on the other hand books II-IX constitute the main body of this great work, and are on the contrary "acroamatique" in nature. We require, however, no dictionary to learn what this ponderous word of Greek derivation means; for Bacon tells us himself in this very work in book VI., chapter II, which treats of various methods for de-

28

livering knowledge, collectively designated as The Wisdome of Delivery. We insert here fac-similes of three original text-pages, 272-274 incl., (Figs. III-V.), in order to place the reader in possession of this valuable first-hand, unadulterated evidence; but the particular passage containing the sought-for definition of the word "acroamatic" will be found on p. 273 (Fig. IV.), and reads as follows:

"Another diversity of Method followeth, in the intention like the former, but for most part contrary in the issue. In this both these Methods agree, that they separate the vulgar Auditors from the select; here they differ, that the former introduceth a more open way of Delivery than is usuall; the other (of which we shall now speake) a more reserved & secret. Let therefore the distinction of them be this, that the one is an Exotericall or revealed; the other an Acroamaticall, or concealed Method. For the same difference the Ancients specially observed in publishing Books, the same we will transferre to the manner it selfe of Delivery. So the Acroamatique Method was in use with the Writers of former Ages, and wisely, and with judgment applied, but that Acroamatique and AEnigmatique kind of expression is disgraced in these later times, by many who have made it as a dubious and false light, for the vent of their counterfeit merchandice. But the pretence thereof seemeth to be this, that by the intricate envelopings of Delivery, the Profane Vulgar may be removed from the secrets of Sciences; and they only admitted, which had either acquired the interpretation of Parables by Tradition from their Teachers; or by the sharpnesse and subtlety of their own wit, could pierce the veile."

In other words, while the ancients published certain books only for private circulation, Bacon distinguishes here a method of delivery of knowledge, or composing of books, which shall be private, concealed or acroamatic. His very clear explanation, taken together with the conclusion forced upon us by the wholly unusual arrangement of the prefatory page about the Emanations of Sciences, is equivalent to distinct notice from the author himself that, while book I of the Advancement of Learning is only a popular preparatory introduction to his high subject, books II-IX,--the main body of the work,--contain a concealed method of delivery or expression, of thoughts and facts, which could not be more openly set forth. Book II. it should also be stated, opens with a formal proem, covering ten pages, indicating that the real entrance for properly qualified students,--or "Sons of Sapience," as Bacon calls them,--lies here!

The problem ahead of a reader, who would attempt the formidable Books of the Advancement of Learning, is therefore to discover, if possible, what concealed methods Bacon used, and

29

30

31

apply them to extracting what he has reserved for our information by such means alone. The example here adduced demonstrates sufficiently, we believe, that such investigations soberly and scientifically conducted are easily justifiable, and, indeed, require no defense.

It should be clear from all that has been said, even thus briefly, that concealed methods of expression in literature have been known and used in past ages by prominent writers, especially also in England; and that, therefore, the works of those, more than others, who mention such methods, must be examined with very unusual care for signs of them in the typography of their first, as well as other early editions, untouched by the devastating hands of ignorant, self-constituted critics, who, as Ben Jonson has said "make more faults, then they mend ordinarily." The acknowledged masters of letters in every country during the Renaissance period and immediately after will be found possessed of incomparably more depth of thought and subtle literary skill in openly or deviously expressing it, than they professed, and are given credit for in our day. They often attained by studied self-effacement such perfect objectivity in their art, as to make it pass for simple spontaneous Nature herself. Unless in our study of their works this is constantly borne in mind, we will err grievously in ascribing superciliously to ignorance or blind chance many things done by design; and this underestimating of past intellectual ability is one of the principal reasons why so many important literary problems concerning that age are still in a state of controversy, instead of being settled by facts, hidden but discoverable in true, unaltered texts. Therein lies our only hope ever to approach closely enough to those rare old masters, to learn for our present profit all the worldly wisdom they can teach.

GEORGE J. PFEIFFER, PH. D.

32

FRANCIS BACON, OR

FRANCIS TUDOR?

(By Amelie Deventer von Kunow of Weimar, Germany)

The name of Francis Tudor is still a new one for the learned and lay world of today, for it occurs as yet in no encyclopedia, historical or literary work. Nevertheless, it has been discovered and been known already for a number of years, by the explorers of Bacon’s secret writings, although outside of the limited circles of the Bacon Societies of England, America, Austria, and Germany, their investigations have received but scant attention.

Who takes the trouble among the great majority of professional students to verify by checking-up those discovered and deciphered writings of Bacon? And how small is the number of those interested in the results which the investigators of Bacon’s cryptography offer! Worthy of admiration surely, and deserving of wider attention, are the labors of those decipherers who have uncovered wholly new facts about Francis Bacon’s, or rather Tudor’s, person and life, for they have discovered already some years ago that the philosopher and statesman, Francis Bacon was a real Tudor by birth, and also the author of the "Shakespeare" plays and sonnets. Because their decipherings, however, contradict all earlier historical and literary work, they obtain neither due consideration nor credence. No doubt the largely prevailing ignorance of cryptography in general, and of the cipher methods invented by Francis Bacon in particular, affords some excuse for, and contributes toward this lack of interest in the achieved cipher solutions of Bacon’s secret writings; so that it is for this reason especially regrettable that the learned world has taken so unsympathetic an attitude. Cryptography is a special field of study made effective by old and new works about this art, and the examination of many secret writings themselves, and these enable us to follow the numerous systems and their uses for the greatest variety of purposes through successive centuries. To discuss this subject in greater detail is not the object of this essay, but it should be emphasized that the invention and use of cipher-methods flourished to the highest degree in the 15th and 16th centuries in all European countries, and especially at all courts of princes.

Although this is well known to most professional students, they persist nevertheless in doubting the discovery and correct solution of many so-called Bacon cipher-works, and even hold them in contempt; but it is cheap and futile criticism, when academic pedants superciliously look down upon decipherers not

33

academically trained; for when once a cipher-solution or key has been found, it is a mere mechanical labor to solve the cipher writing, and this is practised with the greatest success by the experts trained in such work for diplomacy, the secret police, etc.

The doubts about authenticity of the discovery and solution of Bacon’s secret writings are best counteracted by the discovery in the archives of the various countries of documents and records hitherto unknown, especially of such, as historians are compelled to recognize either as state papers, or as valuable material from private archives and libraries, and which demonstrably tally in their main points with the disclosures of the cipher writings of Francis Tudor.

Such discovery of documents and nonciphered letters has been the good fortune of the writer, during several years of her researches about Francis Bacon. The leads which she laboriously followed step by step in Europe, from North to South and again northward in tracing the far-reaching relationships of Bacon’s career, reveal a number of confirmations of the greatest importance for the final clearing up of the facts buried for centuries under the rubbish heaps of historical lies.

Francis Bacon was by birth not a Bacon, but a Tudor. He was the legitimate first-born son of Queen Elizabeth by a secret marriage to Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester and Robert Essex was his own brother, as the second son of this union. *

__________

*NOTE:--While the editor assumes no responsibility for any statements made in these papers, it is remarkable that John Davies of Hereford in his "Scourge of Folly" (1610), addresses a sonnet "To the royall," (!) "ingenious, all-learned Knight,--Sr Francis Bacon," which is here reprinted from the late Sir Edwin Durning-Lawrence’s book "Bacon is Shakespeare." This sonnet is also highly interesting on account of its reference to Bacon’s poetic pastimes, apparently habitual and well known to some people.

"To the royall, ingenious, and all-learned

Knight,--

Sr Francis Bacon

Thy bounty and the Beauty of thy Witt

Comprised in Lists of Law and learned Arts,

Each making thee for great Imployment fitt

Which now thou hast, (though short of thy deserts)

Compells my pen to let fall shining Inke

And to bedew the Baies that deck thy Front;

And to thy health in Helicon to drinke

As to her Bellamour the Muse is wont:

For thou dost her embozom; and dost vse

Her company for sport twixt grave affaires;

So vtterst Law the liuelyer through thy Muse.

And for that all thy Notes are sweetest Aires;

My Muse thus notes thy worth in eu’ry Line,

With yncke which thus she sugers; so, to shine."

34

With this discovery may be brought into chronological relationship also the later events of Francis Tudor’s life, as developed from various and numerous nonciphered sources, which have been either unknown to historians or disregarded by them. All that the historians have heretofore brought forward about Francis Bacon was based, for principal authority, on Camden’s annals.

And old work, however, which appeared first in France in the 17th century and which among other things contains a lengthy treatise on Francis Bacon deserves mention; namely "Le Dictionnaire historique et critique by Pierre Bayle," 2 vols., Rotterdam 1697;--later enlarged and improved editions (with biography of the philosopher Bayle) by Maizeau in 4 vols.,--and numerous translations, for instance into German, by Prof. Johann Christian Gottsched 1741-44.

In this German translation, which was published at Leipzig, one may read on page 358 about Francis Bacon that the people during his youth did not consider him to be a son of the "Bacon" family, but a foster child of Nicholas Bacon, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal, under Queen Elizabeth, sprung from a shepherd family. Later on this assumption was dropped, and many considered Francis as a scion of higher descent!

But this bit of information is given quite briefly without any corroboration or other conclusive disclosure. For the rest, Bayle’s report about Francis Bacon contains only a meager description of his intellectual works and his person. A book which appeared in Amsterdam in 1750 is likewise worthy of note: "Le Nouveau Dictionnaire historique et critique pour servir de supplément ou Continuation au Dictionnaire historique et critique de M. Pierre Bayle par Jacques Georges de Chaufepie." This "Nouveau Dictionnaire" declares that the deserts and talents of that great man Francis Bacon were worthy of a more detailed description than given by Bayle. Chaufepie lays stress upon the philosophical, historical and moral literary works of Francis, but in general adheres to the traditions as Camden has recorded them.

__________

We are well aware that the word "royall" may be taken here to mean magnanimous, generous in gifts, and the like; and will naturally be so understood by most readers. An example of use in this figurative sense occurs in The Merchant of Venice, (1623 folio, Comedies, p. 175, col. 2):

"How doth that royal Merchant good Anthonio;".

But for that very reason the word could also quite safely carry a pointed allusion to royal descent, for those who might know; and this possibility should, therefore, at least be mentioned.

35

While Bayle emphasizes the faults of Francis, Chaufepie endeavors on the contrary to diminish them and so do him more justice.

That the true image of this superlatively great man continued to fade away already in the 17th century was occasioned by the changeful political events in England, which had their beginnings already during his lifetime.

The rising storm-waves of the successive historical events in England, which Francis still witnessed in part during his lifetime, and which afterwards raged on, permitted his memory to be preserved and honored only in the narrow circle of his friends. The English Revolution, the two Civil Wars, the execution of Charles I, and the political disturbances combined with religious struggles,--finally the Republic under Cromwell,--all these had crowded into the background those questions which had arisen earlier, as well as any general interest, about the unique statesman and philosopher, Francis Bacon.

The closing of the theatres by the Puritans also caused a forgetting for a century of the Shakespeare plays; and later on they were without doubt and after some quarrelsome disputes simply revived as the poetical works of the long since forgotten actor.

Francis, however, was held to be in his own country the erstwhile deposed Lord Chancellor, who in 1626 was presumed to have been laid to rest at St. Albans, and then received the well-known monument there in the church of St. Michael through the devotion of his secretary. The majority of his contemporaries therefore remained subject to all kinds of false and unconfirmed suppositions.

Only an intimate circle of friends, and those scattered over various countries, were enlightened about his true life and fate, but all of them had, according to the then prevailing custom of "Bonds" and in this case as members of Bacon’s "Secret Society" sworn utter silence about their knowledge of his secrets.

Hence there remained to be accepted as facts by the next-following generation, only what the annals of Camden had recorded of him, besides the works already published by him, and further the publication of divers manuscripts by men especially selected by him. These various editors, carefully selected by Francis, as well as his directions for the custody of manuscripts not to be published, permit our concluding that he left behind, in part, such as he desired to have kept secret for the time immediately after his death and yet securely preserved.

In the examination of and further search for Bacon manu-

36

scripts, it is worthy of note that after more or less considerable intervals, some heretofore unknown manuscripts still continue to be found by investigators, and we have even today to reckon with the possibility of discovering new ones in some of the archives of divers countries. Researches about Francis Tudor can therefore by no means be regarded as terminated, but rather advanced already so far, that we may rely on archival proofs to determine his status as a Tudor, and in this connection, on the strength of nonciphered letters, as the author of the dramas.

It requires indefatigable labor to make headway against the historical falsehood set on foot by Camden’s Annals, and for centuries past as firmly anchored as military fortifications. Camden’s representations arose at the court of Elizabeth and James I, under the influence of Bacon’s enemies, making it appear to the unsuspecting student that the historian Camden himself was one of them.

Spedding was the first who succeeded in shedding a more favorable light upon the great Bacon, by publishing his philosophical and other works in 7 volumes, and his letters in 7 more, and giving in so doing many suggestions for a more correct appreciation of that greatly misjudged man. Yet he, too, fears, as he says in his preface, being accused of too one-sided a view of him.

In this we see proof that until the end of the last century, when the last volumes of Spedding’s work appeared, the old ignorant prejudices against Bacon still prevailed.

It remains, therefore, an interesting task for our own age, after tearing asunder the tissue of the principal lies about Francis Tudor to study him as the great Tudor, and the entire literature which flowed from his golden pen, as the intellectual creations of the man in whom was embodied to an incomprehensible degree, that genius which, extending its power afar through the centuries, must be conceded to be the greatest glory of England, and at the same time the international property of all lovers of learning and literature.

In the course of these researches, not only the burning question arises of "Bacon or Shakepere." The investigator’s probe must penetrate much deeper, in order to grasp all the manifold single facts of the life of this prince, equipped with Tudor strength, who, chastened by the experiences of a bitter fate, full of self-denials, both as philosopher and greatest poet, explored and illumined all the vital questions affecting mankind, with the profound wisdom and the rich creative power of his genius.

37

Even though his philosophical works must be measured by the standard of the opinions of his age, those writings nevertheless give proof of a vision far beyond it. By his eminent powers of mind, he far outranked his contemporaries. There is hardly a field of knowledge in which he has not proved himself a master. His eloquence made him a famous parliamentary orator. Spedding points out the brilliant literary style of his works, and even testifies that he far excelled the best of contemporary authors, in forceful forms of speech and expression. He asserts, too that his majestic language may be placed on a par with only one other,--the mighty language of Shakespeare!

Spedding has advanced thus far, but unhappily it was denied him to perceive the truth, namely that under the pseudonym "Shakespeare" was hidden the philosopher Francis Tudor.

It will remain a vain effort of literary historians to continue to hold up the uneducated actor Shakspere as the poet of the "Shakespeare" dramas by all manner of artificial and strained proofs.

Whoever, like myself, has had the good fortune to approach the study of Francis Bacon and his works, without any foreknowledge whatever of this particular contention about "Bacon or Shakespeare" and without any previous acquaintance with Bacon’s secret cipher works, which I admire all the more now,--may well follow as a guide for his investigations the method recommended by the famous historian Leopold von Ranke, who says: "Modern history is no longer to be based upon the reports of even contemporary historians, let alone upon further elaborations derived from them, but rather to be built upon the accounts of eye-witnesses and the most genuine actual documents." In pursuing such a method, the explorer of the past becomes aware that he must spare no means or effort to reach the original sources and to ferret them out in the various countries.

By the discovery of these original documents, which, however, can by no means be as yet considered exhausted, the comparison of the truth with the discoveries of decipherers about Francis Tudor, is greatly facilitated and their decipherings should therefore be received with satisfaction.