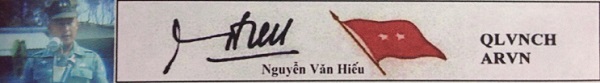

General Lam Quang Thi

Home for the weekend recently, I chanced upon my father's South Vietnamese Army uniform, the three silver stars still pinned meticulously onto each lapel. Once in that tropical country, my father had worn it regally, a warrior in a civil war he bravely fought and lost. Once, as a child, I had looked up to a man who had seemed more like a deity. Hadn't I imagined myself as an adult walking in his soldierly footsteps?

A particular night emerges from my childhood memories: the cool wind blows through a villa where distant B-52 bomb explosions echo, melding with the monsoon rain. I am 10 years old, an army brat living with my family in the imperial city of Hue, near the DMZ (demilitarized zone). Somewhere in the servant quarters our two German shepherds are barking loudly as a few army jeeps screech to a halt on the cobble stone courtyard.

"Papa's home! Papa's Home"! I yell and rush to him -- he laughs heartily as he lifts me up for a warm embrace. His wet uniform emits the smell of sweat, cologne, mud, cigar and gunpowder -- smells that I will always associate with the battlefield. But it does not matter -- I am happy in that embrace, happy in that house by the Perfume River when history was still on our side.

A few years later, however, the war ended -- badly for us. When we set foot on the American shore, history was already against us; Vietnam went on without us; America went on without acknowledging us. In America, there were no territories for father and son to defend, no war to fight. Instead, a gap slowly widened between us.

Though he managed to remake himself as a banking executive with an MBA -- a remarkable feat for someone who came to America in his 40s and who spoke English as his third language -- my father's passion remains extraterritorial. At dinner time, after a drink or two, he would relive the battles that he had fought and won. The Vietnam war has become for him "a twenty-five years century" -- the epitome of his life.

My father's booming voice shook every pane of glass in our new home and filled me, slowly but surely, with an impending sense of doom. His war, my inheritance; his defeat, my legacy. By the time I was 12, I, too, had become a bitter veteran of a war -- but one I had never actually fought.

What my father rarely mentioned was the last time he wore his uniform -- the day South Vietnam surrendered. My father had commandeered a navy ship full of army officers to the Philippines. Nearing shore, he changed into a pair of jeans and a T-shirt, threw his gun into the Pacific Ocean, and asked the U.S. for asylum. I was not there but that image, more than any other, spelled the end of my childhood mythology.

When I turned 18, my father -- a big fan of Napoleon -- took the family to Europe for vacation. Paris, where he had once been a foreign student, was the main attraction but he insisted on seeing the battlefield of Waterloo in Belgium. We spent hours driving through the Belgian countryside until, at last, we found the place. Climbing to the top of the hill overlooking the field, my father began narrating where Napoleon's army stood, and how the Duke of Wellington arrived just on time to turn the tide. I already knew the story and I was no longer intrigued. I suddenly realized that passions are not inherited -- that what the pasture I was gazing at invoked in me was not a martial ethos but poetry.

Somewhere in between the boy who once sang the Vietnamese national anthem in the school yard in Saigon with tears in his eyes and the young man preparing to go to college believing in his own power to shape his destiny was the slow but natural demise of the old patriotic impulse.

Indeed, the Cold War and its aftermath has given birth to a race of children like me -- transnationals. The greatest phenomenon in this century, I am now convinced, has less to do with the World Wars than with the dispossessed those wars sent fleeing. Today displacement -- movement -- has become the contemporary narrative.

Today in America my father watches CNN and practices his martial arts. He does not expect history to be kind and is, therefore, not an unhappy man. He watches the collapse of communism around the world with glee and sips his wines. In his mid-60s, he is a graying panther who recently finished his soldier's memoir so that, in his words, "the new generation of Vietnamese Americans will know what happened." Perhaps one day, when communism fails there too and democracy reigns, my father will return to Vietnam, if only to dance one last dance on his enemies' graves.

Whereas I...

Every morning I write, rendering memories into words. Only this morning, waking from a recurrent dream in which I am diving into the ocean to retrieve a rusty gun, do I begin to appreciate how tricky history is, how powerful its grip on one's soul. Always in the dream I reach out for the gun but it dissolves into sand. Every morning I write, going back further, re-invoking the past precisely because it is irretrievable. I write, if only to take leave.

A kiss then for my father as the weekend visit ends. I tear a hole through the army uniform's plastic cover, lean close and sniff. There is no odor now of gun powder, no smell of scorched earth, no cigar stench -- only the faint smell of mothballs, old dust.

Andrew Lam

http://www.pacificnews.org/lam/index.html