Theodore Roosevelt

1858-1919

Twenty-Sixth President of the United States of America

"The credit belongs to those who are actually in the arena, who

strive valiantly, who know the great enthusiams, the great devotions,

and spend themselves in a worthy cause; who, at the best, know the

triumph of high achievement and who, at the worst, if they fail, fail

while daring greatly so that their place shall never be with those cold

and timid souls who know neither victory nor defeat."

"Theodore Roosevelt"

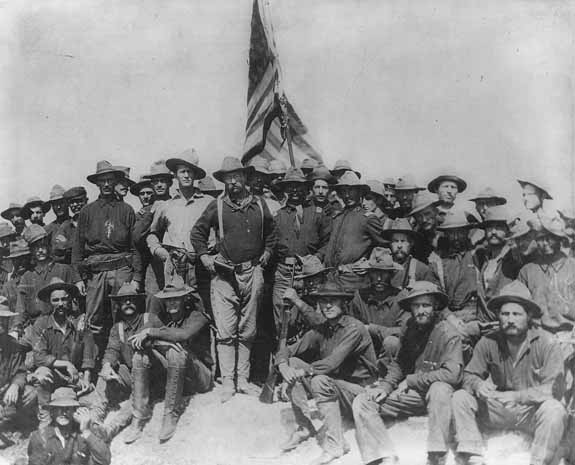

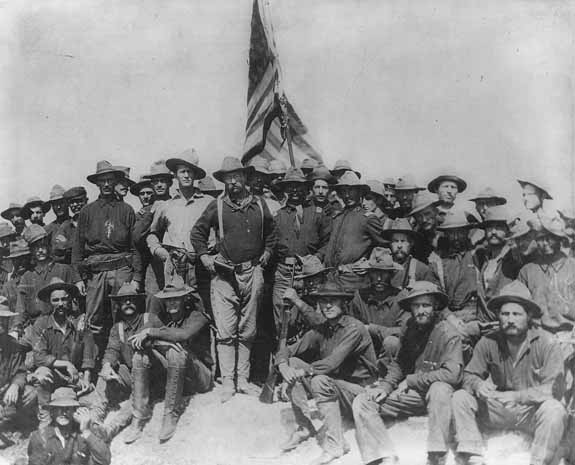

Then Lieutenant Colonel Teddy Roosevelt - US Army, and his Rough Riders

Then Lieutenant Colonel Teddy Roosevelt - US Army, and his Rough Riders

at the top of the hill, Battle of San Juan, during the Spanish-American War

Who Were the Rough Riders

There was Woodbury Kane, an Ivy League dandy,

Joe Stevens, the world's greatest polo player,

Dudley Dean, the famed Harvard quarterback,

Bob Wrenn, the nation's number-one-rated tennis player.

Hamilton Fish was there too, former captain of the Columbia crew,

and there were footballers from Princeton, high-jumpers from Yale,

gentlemen huntsmen named Wadsworth and Tiffany,

and elegant blue-blooded Englishmen.

You've heard so much about them,

and you never knew any of their names ......

They were Teddy Roosevelt's "Rough Riders"

In April of 1898 McKinley was president,

Teddy Roosevelt was Assistant Secretary of the Navy,

and we were at war with Spain.

On Monday 25 April 1898, it was announced that

Teddy would be recruiting for the First U.S. Volunteer Cavalry.

By Wednesday, twenty-seven sacks of applications had been received.

Twenty-three thousand men, enough for an entire division,

all begging Teddy for the opportunity to serve under him.

The formal designation "First U.S. Volunteer Cavalry" was quickly ignored,

especially by the newspapers out west.

"Teddy's Terrors" newsmen began calling them, "Teddy's Texas Tarantulas",

"Teddy's Gilded Gang", "Teddy's Cavalry Cowpunchers",

"Teddy's Cowboy Contingent", "Roosevelt's Rangers",

"Roosevelt's Riotous Rounders", and every imaginable alliteration.

There was only one appellation of which Teddy himself fully approved:

"Roosevelt's Rough Riders"

He had used the term himself, as early as 1896

He had said that he longed to lead a troop of "Rough Rders" into battle

And now he would resign as Assistant Navy Secretary to do so

In addition to some of Roosevelt's Ivy League recruits,

aristocratic young gentlemen who arrived for training in San Antonio

wearing custom leather boots and shirts from Abercrombie and Fitch.

Yet in addition to the eastern college athletes and dandies, there were

policemen, coal miners, and cowboys, especially cowboys.

They compromised approximately three-fourths of the entire Regiment.

Recruits who did not measure up wept openly upon learning that

they would be left behind.

The lucky ones, the 560 who remained,

were off to fight the Spanish on Cuban soil.

Teddy and His Rough Riders are all most of us remember

about the Spanish-American War:

Teddy Roosevelt leading the Rough Riders' charge up San Juan Hill

That battle it is said, carried Teddy to the White House.

But how many of us know

"THE REST OF THE STORY"

The actual site of the charge was Kettle Hill, not San Juan Hill

Teddy's Rough Riders were not really Teddy's

The First U.S. Volunteer Cavalry was actually under the command of

Colonel Leonard Wood

Teddy was second in command

When the Rough Riders embarked on the Cuba-bound troopships,

they were informed that there would be no room for their horses

Teddy's men actually charged up Kettle Hill on foot

Roosevelt's Rough Riders were neither Roosevelt's,

nor throughout the entire Spanish-American War, did they ride

The energetic Republican President had taken his first oath of office upon the

death of President McKinley, who died of an assassin's gunshot wounds on

September 14, 1901. Mr. Roosevelt had been President himself for three years at

the election of 1904. The inaugural celebration was the largest and most diverse of

any in memory—cowboys, Indians (including the Apache Chief Geronimo), coal

miners, soldiers, and students were some of the groups represented. The oath of

office was administered on the East Portico of the Capitol by

Chief Justice Melville Fuller

Theodore Roosevelt

Inaugural Address

Saturday March 4, 1905

My fellow-citizens, no people on earth have more cause to be thankful than ours,

and this is said reverently, in no spirit of boastfulness in our own strength,

but with gratitude to the Giver of Good who has blessed us with the conditions

which have enabled us to achieve so large a measure of well-being and of happiness.

To us as a people it has been granted to lay the foundations of our national life

in a new continent.

We are the heirs of the ages, and yet we have had to pay few of the penalties

which in old countries are exacted by the dead hand of a bygone civilization.

We have not been obliged to fight for our existence against any alien race,

and yet our life has called for the vigor and effort without which the manlier and

hardier virtues wither away.

Under such conditions it would be our own fault if we failed, and the success

which we have had in the past, the success which we confidently believe the

future will bring, should cause in us no feeling of vainglory, but rather a deep

and abiding realization of all which life has offered us, a full acknowledgment

of the responsibility which is ours, and a fixed determination to show that under

a free government a mighty people can thrive best, alike as regards the things

of the body and the things of the soul.

Much has been given us, and much will rightfully be expected from us.

We have duties to others and duties to ourselves, and we can shirk neither.

We have become a great nation, forced by the fact of its greatness into relations

with the other nations of the earth, and we must behave as beseems a people

with such responsibilities.

Toward all other nations, large and small, our attitude must be one of cordial

and sincere friendship.

We must show not only in our words, but in our deeds, that we are earnestly

desirous of securing their good will by acting toward them in a spirit of just

and generous recognition of all their rights.

But justice and generosity in a nation, as in an individual, count most when

shown not by the weak but by the strong.

While ever careful to refrain from wrongdoing others, we must be no less

insistent that we are not wronged ourselves.

We wish peace, but we wish the peace of justice, the peace of righteousness.

We wish it because we think it is right and not because we are afraid.

No weak nation that acts manfully and justly should ever have cause to fear

us, and no strong power should ever be able to single us out as a subject for

insolent aggression.

Our relations with the other powers of the world are important, but still more

important are our relations among ourselves.

Such growth in wealth, in population, and in power as this nation has seen

during the century and a quarter of its national life is inevitably accompanied

by a like growth in the problems which are ever before every nation that

rises to greatness.

Power invariably means both responsibility and danger.

Our forefathers faced certain perils which we have outgrown.

We now face other perils, the very existence of which it was impossible

that they should foresee.

Modern life is both complex and intense, and the tremendous changes wrought

by the extraordinary industrial development of the last half century are felt in

every fiber of our social and political being.

Never before have men tried so vast and formidable an experiment as that of

administering the affairs of a continent under the forms of a Democratic republic.

The conditions which have told for our marvelous material well-being,

which have developed to a very high degree our energy, self-reliance,

and individual initiative, have also brought the care and anxiety inseparable

from the accumulation of great wealth in industrial centers.

Upon the success of our experiment much depends, not only as regards

our own welfare, but as regards the welfare of mankind.

If we fail, the cause of free self-government throughout the world will

rock to its foundations, and therefore our responsibility is heavy,

to ourselves, to the world as it is to-day,

and to the generations yet unborn.

There is no good reason why we should fear the future, but there

is every reason why we should face it seriously, neither hiding from

ourselves the gravity of the problems before us nor fearing to approach

these problems with the unbending, unflinching purpose to solve them aright.

Yet, after all, though the problems are new, though the tasks set before us

differ from the tasks set before our fathers who founded and preserved

this Republic, the spirit in which these tasks must be undertaken and these

problems faced, if our duty is to be well done, remains essentially unchanged.

We know that self-government is difficult. We know that no people needs

such high traits of character as that people which seeks to govern its affairs

aright through the freely expressed will of the freemen who compose it.

But we have faith that we shall not prove false to the memories of the

men of the mighty past.

They did their work, they left us the splendid heritage we now enjoy.

We in our turn have an assured confidence that we shall be able to leave

this heritage unwasted and enlarged to our children and our children's children.

To do so we must show, not merely in great crises, but in the everyday affairs of life,

the qualities of practical intelligence, of courage, of hardihood, and endurance,

and above all the power of devotion to a lofty ideal, which made great the men

who founded this Republic in the days of Washington, which made great the

men who preserved this Republic in the days of Abraham Lincoln.

Click Here To

Return To The Site Options

"Al Varelas's USMC Web Site"