Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields:

Texas: Northwestern Fort Worth area

© 2002, © 2016 by Paul Freeman. Revised 8/14/16.

This site covers airfields in all 50 states: Click here for the site's main menu.

____________________________________________________

Please consider a financial contribution to support the continued growth & operation of this site.

Eagle Mountain Lake MCAS / Newark Airport (revised 5/12/16) - Oliver Farms Airfield (revised 10/25/14)

Rhome MCOLF (revised 6/29/15) - Saginaw Airport (revised 8/14/16) - Taliaferro Field #1 / Hicks Field (revised 5/12/16)

Taliaferro Field Bombing Target (revised 8/29/06)

____________________________________________________

Saginaw Airport (F04), Saginaw, TX

32.86, -97.38 (Northwest of Fort Worth, TX)

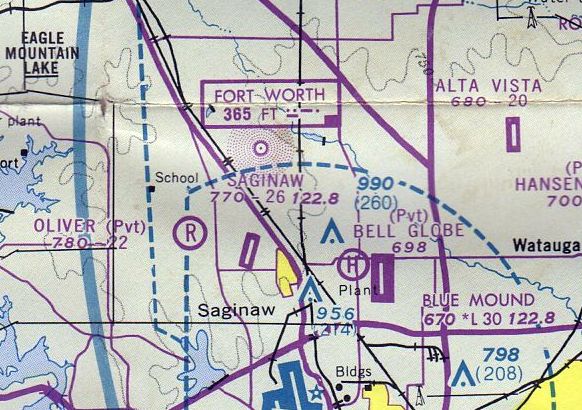

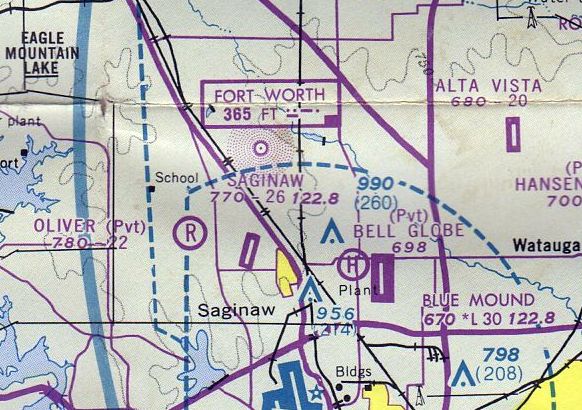

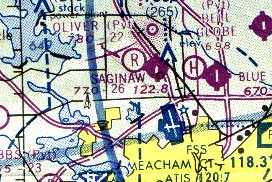

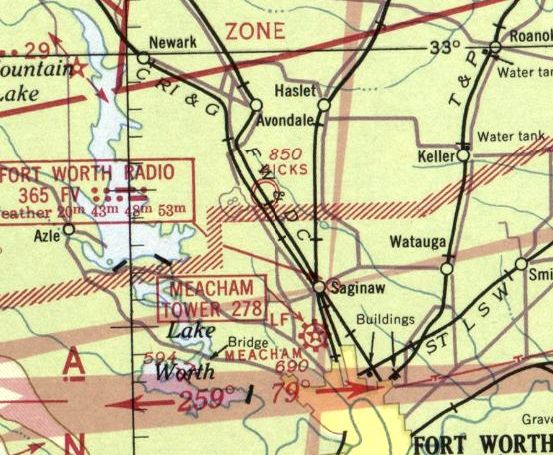

Saginaw Airport, as depicted on the March 1947 Dallas Sectional Chart (courtesy of Chris Kennedy).

Saginaw Airport is one of the large number of general aviation airports

which have been swallowed up by "development" in the Dallas - Fort Worth metro area.

Saginaw Airport was not yet depicted on the March 1946 Dallas Sectional Chart.

According to an article entitled "A Home for Slow Airplanes" by Walt Shiel,

Saginaw Airport was built by John MacNeil shortly after WW2.

It originally had only a grass runway & an aluminum maintenance hangar.

The earliest depiction of Saginaw Airport which has been located

was on the March 1947 Dallas Sectional Chart (courtesy of Chris Kennedy).

The 1948 USAF Urban Area Chart depicted "Saginaw Airfield"

simply as a rectangular outline, without any depiction of runways.

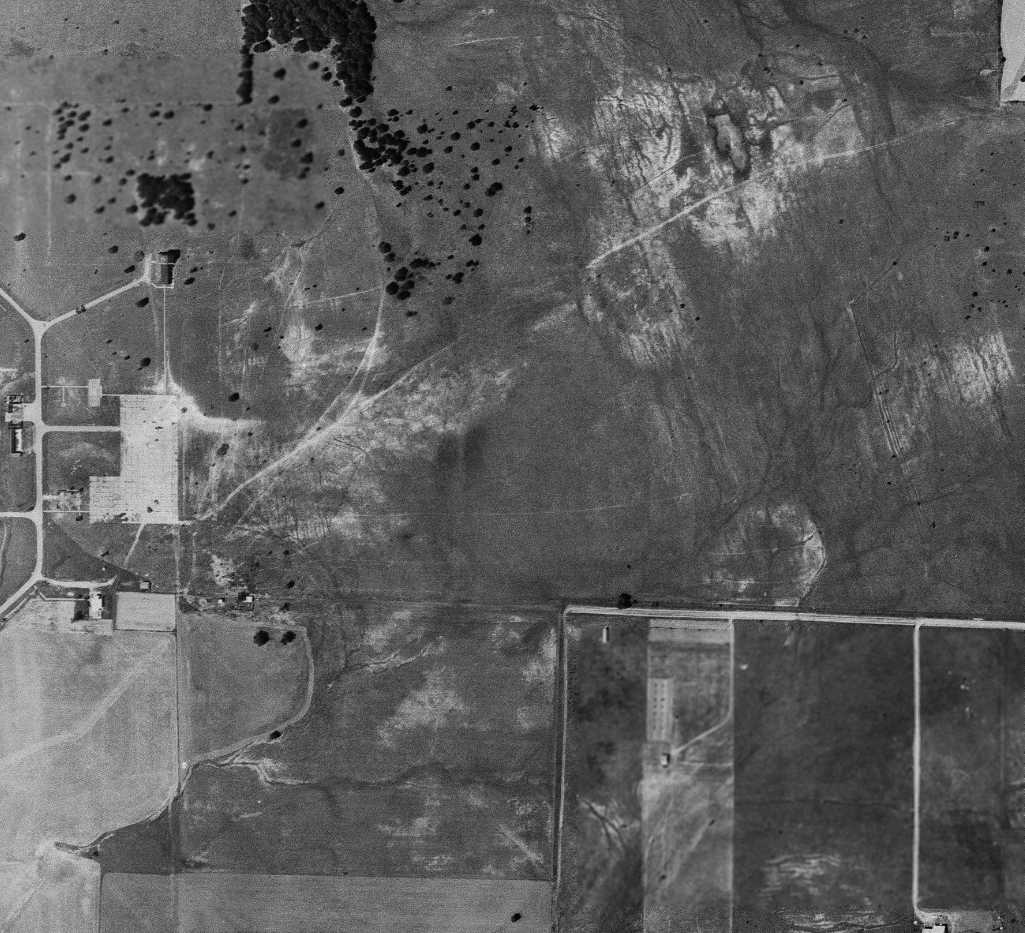

The earliest photo which has been located of Saginaw Airport was a 1952 aerial view.

It depicted the field as having 2 runways,

with a cluster of hangars & 4 light aircraft on the south side.

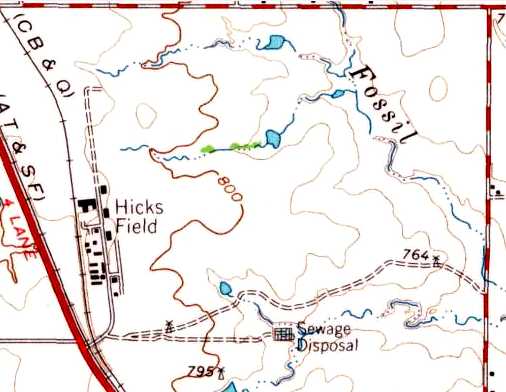

The 1955 USGS topo map depicted Saginaw Airport

as having 2 unpaved runways, with numerous buildings on the south side of the field.

A 1956 aerial photo still showed Saginaw Airport having unpaved runways.

Saginaw had gained a paved runway at some point between 1956-62,

as the 1962 AOPA Airport Directory described Saginaw Airport

as having a 2,650' hardtop Runway 18/36 & a 2,400' turf Runway 13/31.

The operator was listed as a J. D. McNeill Jr.

A 1963 aerial view showed Saginaw's newly-paved Runway 18/36.

Ganey Bradfield recalled, “Saginaw Airport was run by a man named McNeill.

He was pretty grouchy & rather 'by the book'.

His wife did most of the day to day operation stuff.”

The 1963 TX Airport Directory (courtesy of Steve Cruse)

depicted Saginaw Airport as having a row of T-hangars along the west side, 3 rows of t-hangars east of Runway 18/36,

and the office & main hangar adjacent to the ramp.

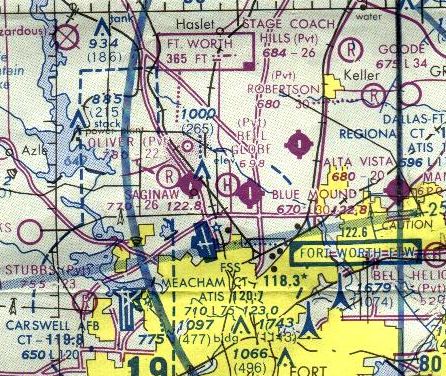

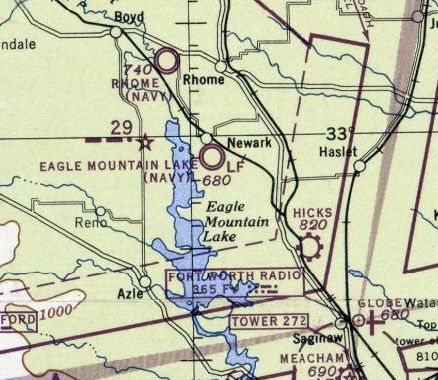

Saginaw Airport, as depicted on the 1964 DFW Sectional Chart (courtesy of Ross Richardson).

Eddie Shaw recalled, “I learned to fly out of Saginaw, started flying there in September 1965 & soloed in February 1966.

J.D. McNeil operated 2 Cessna 140s & an Aeronca Champ in the flying school.

The late-model (1950) 140A was the preferred airplane, but of course came with a premium price, like $13/hour,

so I flew the Aeronca most since it was less expensive, something like $9/hour, although I did solo in one of the 140s.

My dad taught me to fly so I saved money on the dual instruction part.

J.D. was a retired American Airlines pilot & was pretty crusty, his wife did most of the 'public relations' but they ran a very nice airport.

In November 1967 I also got my multi-engine rating at Saginaw in a Cessna 310B that J.D. McNeil had in the school.”

I will always remember those days at Saginaw, the airports just aren't the same now.”

The 1967 TX Airport Directory (courtesy of Brad Stanford) listed the operator at Saginaw as McNeill Flying Service.

The earliest photo which is available of Saginaw Airport was a 1970 aerial view.

It depicted the field as having one paved runway & one grass runway.

Several hangars were visible on the south end of the field, as well as 5 light aircraft.

Lane Crabtree recalled, “Saginaw Airport... I learned to fly there in 1974/75

and continued to fly out of there for another 5 or so years after I got my Private Pilot ticket.

I learned on their 2 Cessna 140s mostly, but flew their 150 for night hours & other times that we needed a working radio.

The 140s were pretty much daytime only flyers and had old, almost useless, radios.

But, I enjoyed the 'rag wing' 140 as it had much better performance over the all-aluminum 140A.

They also had a nice Cessna 182 with two 42 gallon long-range tanks that was lots of fun to fly.

Never got enough hours to qualify to fly their Bonanza. I did get a few short hops in their 2 Cessna 310s.

I also worked out there for a year from about 1975-76, doing usual airport duties such as refueling, towing, and maintenance.

Supposedly, I thought I'd get some cross country flights with McNeil, but that never happened.

At $2.50 an hour, I certainly wasn't there for the money.

After it appeared I wasn't going to get invited on Air Taxi & Air Ambulance flights with McNeil, I found work elsewhere to pay for flying time.

I will say it was interesting to hear some of the flying stories told by McNeil in the office on days where it was raining or otherwise not great flying weather.

As some have said, he could be a bit gruff, but it wasn't directed at you personally, just the way he was.

Other pilots & airport bums dropped by from time to time who had their own great stories & jokes.”

Lane continued, “Just before I got my license, long time Saginaw Airport A/E mechanic Richard Burton got cancer, and passed away a year later.

That left Bob Eggenburger to do most of the annuals & other maintenance after he got off his day job at General Dynamics.

Bob was a real workhorse & never seemed to sleep. I don't know how he did it all.

Most of the 'airport bums' as we called them, were professionals such as MD's, oil men, engineers & quite a few owned Bonanzas.

We also had a former Air Force test pilot, Richard Johnson, who owned an early V35, who once held the speed record in an F-86.

He later flew the F-111 as a GD test pilot. Pretty good guy & he gave me a free biennial checkride once.”

The July 1976 DFW Terminal Chart (courtesy of Jim Hackman) depicted Saginaw as having a 2,600' paved runway.

The last aeronautical chart depiction which has been located of Saginaw Airport was on the 1978 Dallas Sectional Chart,

which depicted Saginaw as having a 2,600' paved runway.

A 7/12/79 photo of N81331, a 1946 Fairchild 24R-46, serial #R46231, at Saginaw Airport.

A late 1970s / early 1980s photo of “Lane Crabtree refueling a Cessna 400 series at the fuel pit” at Saginaw.

A late 1970s / early 1980s photo of “Lane Crabtree exploring the hulk of a Twin Beech that sat on the airport for decades” at Saginaw.

A late 1970s / early 1980s photo by Lane Crabtree of the “Saginaw Airport office.

Mrs. McNeil's office was behind the pocket door. The office was spartan, but functional.”

According to an article entitled "A Home for Slow Airplanes" by Walt Shiel,

John MacNeil sold Saginaw Airport & its 150 acres when they retired in the early 1980s.

The new owner sold off a 40 acre parcel to a grocery store chain,

shrinking the size of the airport.

However, the new owner stopped making payments on the remainder of the property to MacNeil,

causing MacNeil to repossess the airport.

The airport had been allowed to deteriorate by the second owner,

necessitating much cleanup work.

A September 1983 photo of N1541D, a 1952 Cessna 195, serial #7763, inside a Saginaw Airport hangar.

By 1985, the manager was listed as Scotty Boggs in the 1985 TX Airport Directory (courtesy of Steve Cruse).

Brian Goad recalled, “I used to fly an L-4 & a Stinson 108-1 out of Saginaw

in the late 1980s & early 1990s when TMark Aviation was operating it.

On occasions, Mark used to let me fly his yellow Cub he had beautifully restored;

it was a special treat for me to do so.

His restored Cub looked & felt as though it had just rolled off Piper’s assembly line;

I should have bought it when he offered to sell it to me.”

Brian also flew an L-4 from Saginaw.

“After Oliver Farms closed, the L-4 was brought over to Saginaw.

My dad owned the L-4, but since he was so busy flying the BT-15,

he asked me to maintain it & fly it to shows… I couldn’t have asked for a better deal.

For several years, the L-4 occupied the second stall from the west on the south side of the middle 3 T-hangars.”

Brian recalled, “The best times of my life were spent at our Saginaw play days

and even on raining days sitting in the big hangar drinking beer & telling stories.

Usually, everyone with the little birds would come out after work on Friday evenings,

go dog fight for a bit, disengage mock battle to enjoy the countryside for a little while,

then come back joining up to do a little formation flying.

It wouldn’t take long & the parking lot would be dotted with spectators

(including the Saginaw Fire Department & their fire truck)

all asking if there was an air show going on.

We must have looked pretty impressive in the Cubs, Champs, and L-birds.

After the flying was done, well of course it was beer time, more stories,

and endless joking & laughing, or even help add a stitch or two to one of Mark’s projects.

Saginaw Airport was the place to be on a Friday evening or Sunday.

I have many fond memories of the Saginaw days; they were the best.”

Brian continued, “It was a small world for me there at the airport.

Mark Heffley’s younger cousin Todd Heffley had a Champ based there.

I was friends with Todd’s older sister when he was just a little kid.

I recall Todd threw acorns at me & squirted me with the water hose back then.

Now that 'little kid' was flying off my wing.

The small world continued when another Cub owner named Tim showed up; his wife was in my high school class.

Then there was John Gronemeyer with his L-5.

I had met John through the Confederate Air Force.

So with Mark, Todd, Tim, John, a few others, and I, we kept Saginaw Airport very active & a fun place to be.”

Brian described the grass strip at Saginaw as “the smoothest I had ever touched down on.

It was so smooth you never knew when you crossed over the asphalt.

However, some pilots made it a contest to touch down on the grass

before crossing the dirt taxi strip that lead to the hangars on the west side.

But if you didn’t get it just right, that little dirt hump would bounce you back up into the air

like a Harrier Jump Jet taking off a curved deck.

I never could do it right; needless to say, I always landed long in the grass & made ‘perfect’ landings every time.”

Brian continued, “I did have to use the grass cross runway once.

While I was out & about in the L-4, the wind had picked up out of the southeast,

and so strong that I managed to touch down & stop in about 30 to 40 feet.

Good thing I had an excellent instructor for tail-dragger,

otherwise I probably never would have been able to taxi back to the hangar, the wind was that bad.”

Brian continued, “Now, Saginaw did not have a lighted runway;

however, there were times some of us flying the little birds got caught out after dark.

Should this happen, us locals would execute the ‘Dairy Queen Approach’ to Saginaw.

The Dairy Queen to the north of the airport had a huge American flag brightly lit,

and that was our marker to turn due south & less than a mile you would be lined up over the runway

to make a north to south low pass checking for obstacles on the runway (i.e. cars, motorcycles, or coyotes).

Mark was always checking to see who hadn’t made it back in before dark

and he would leave the shop lights on which marked the south end of the runway.

This was important since holding a 2-D cell flashlight out the door never made for a good landing light on the L-4,

and especially since it took both hands to land the plane.”

Brian continued, “It was the opinion of most of the local pilots at Saginaw

that the student pilots flying in & out of Meacham Field had no clue that another airport (Saginaw)

was near their parallel runway approach centerlines.

The small planes coming into Meacham were always off line and/or too low,

and constantly invading our airspace.

We had to keep a close watch for those students & be ready to bale out west or simply dive for the runway;

I got plenty of practice ‘slipping’ the L-4 in.”

In 1990, Saginaw was leased by John MacNeil to Mark & Tara Heffley.

They operated TMark Aviation, which specialized in restoration of tail-draggers.

Paul Johnson recalled, “I rented hangar space from Mark & Tara from August 1992 until September 1996.

I rented the (very) little garage apartment behind Mr McNeill's house from January 1993 until August 1996.

Living with my airplane really impressed the young women I was dating back then...

until they got to know me... hah!

Some of THE happiest days of my 41 years of life were spent committing aviation at F04...

until April 1996 when Mark was diagnosed with brain tumors, which would not stop growing back when removed.

Mark graduated from this life in October 1996, at the age of 42.

Tara made a magnificent attempt to keep T-Mark Aviation aloft, but the deck was stacked against her.

The elderly Mr. McNeill's daughter Barbara had really talked up the idea of making F04 an airpark,

but no attempts to bring this to fruition were ever seen by any of us.

The general consensus among Saginoids & lurkateers

was that Barbara was simply biding her time until she could do as she pleased.”

Paul continued, “I first experienced F04 in July of 1992,

when, a-shopping for hangar space for my 'Baby 180' (fastback tailwheel 1962 C-150),

I drove my truck onto the runway following Cooper Heffley (Lenard Loopner's youngest child) on his dirtbike,

leading me to meet the airport manager (Mark), who was flying radio-controlled models with Lynn & their younguns.

They had parked 'Paw Paw Heffley's' immaculate early-model GTO out there on the east shoulder of the runway

and were enjoying refreshing sudsy beverages while entertaining & instructing their younguns

with radio-controlled antics of derring-do.

They offered me such a beverage & it occurred to me as I imbibed that I might have found My People.”

Paul continued, “The pre-start checks were amended by Lenard Loopner to include the admonition, 'RUN AWAY!'

A good start, takeoff, landing (especially), low pass, high speed pass,

batch of fajitas or extremely 'coldbeer' was termed 'ECK-cellent!'

Barf-bags were proffered to nervous first-time passengers

during our highly professional pre-flight briefings with the gentle advice,

'If yer gonna spew, spew in this.'

Of course the crinkled nose & high-pitched inflection & lisp of Garth Algar made it all the more effective.

If a particular crosswind, fastener combination, elusively dropped essential part,

extra-hot batch of salsa, decidedly pitched game of pool in the lobby, or too-stiff drink

were too much for one of our crowd, we entreated our compatriots for assistance with,

'It sucking my will to live!' & if greatly challenged, 'Oh the HUMANITY!'”

Paul continued, “It was once determined that all the trees trying to grow up through the westside T-hangars should be cut down.

Mark, Todd, another corporate pilot named Mike Canaday & myself assayed to effect such clean-up.

It was quite a weekend of hard work & hair-raising crashes of the mighty chinaberry to earth.”

Paul continued, “Tara in the mid 1990s hadn't flown professionally for 10 years,

due to making babies & founding T-Mark,

and she STILL had more hours than Mark.

Mark took a lot of ribbing about that... but he just grinned... because he had... her!”

Paul continued, “Lynn Heffley, Mark's brother & Tim Carter's co-owner in a couple of aircraft,

lived in Mr Mcneill's house for the first several months that I was there.

Then a corporate pilot/furloughed USAIR pilot named Steve Wilkey was there for few months.

He co-owned a Pitts S-1S with Billy Brock, who with 500 hours total time,

made a flawless pasture-landing in it near Decatur when it threw a rod.

Then Todd & Cindy Heffley lived there with Gee Bee, their little orphan pup from the pound,

probably the last 2 years I was there, & for a while afterward.

A corporate pilot named Alex Knezky moved into the garage apartment in September 1996,

when I moved to my new place at Rhome Meadows.

I love that F04 & dem Hoeflexes, Saginoids & lurkateers.

Oh how my heart yearns for a return to such blissful days & fast friendships which weren't shallow.

Words cannot how profoundly my life has been impacted as a result of my season as a Saginoid.

There are F04-shaped voids in many hearts.”

Tim Carter recalled, "I hangared a Pitts S2B there for a while (in the main hangar).

About once a month during the summer we would have a 'Cub Sunday'.

Usually advertised at nearby airports & sometimes catered by a local restaurant.

They were well attended & many rides were given to visitors."

"I'll stake claim to the last student known to fly his initial solo at Saginaw.

I soloed my son, Patrick Carter there on 5/3/98.

There could have been some since then, but I don't know of them,

and will claim the title until someone steps forward with a later date.

Patrick soloed in a Henderson Little Bear which is a J-3 Cub replica.

There were few years afterward there that someone else could have [soloed],

but the airport was not very active then & there was no commercial operation there at all (other than gas sales).

The grass area on the sides of the runway were used for landing as well as the pavement.

It was probably the smoothest grass strip I ever landed on."

Saginaw's grass Runway 13/31 was evidently abandoned at some point between 1985-95,

as a 1995 USGS aerial photo showed the the crosswind runway no longer cleared.

No planes were visible on the field.

The 2000 AOPA Airport Directory described Saginaw as having a single 2,600' asphalt Runway 18/36.

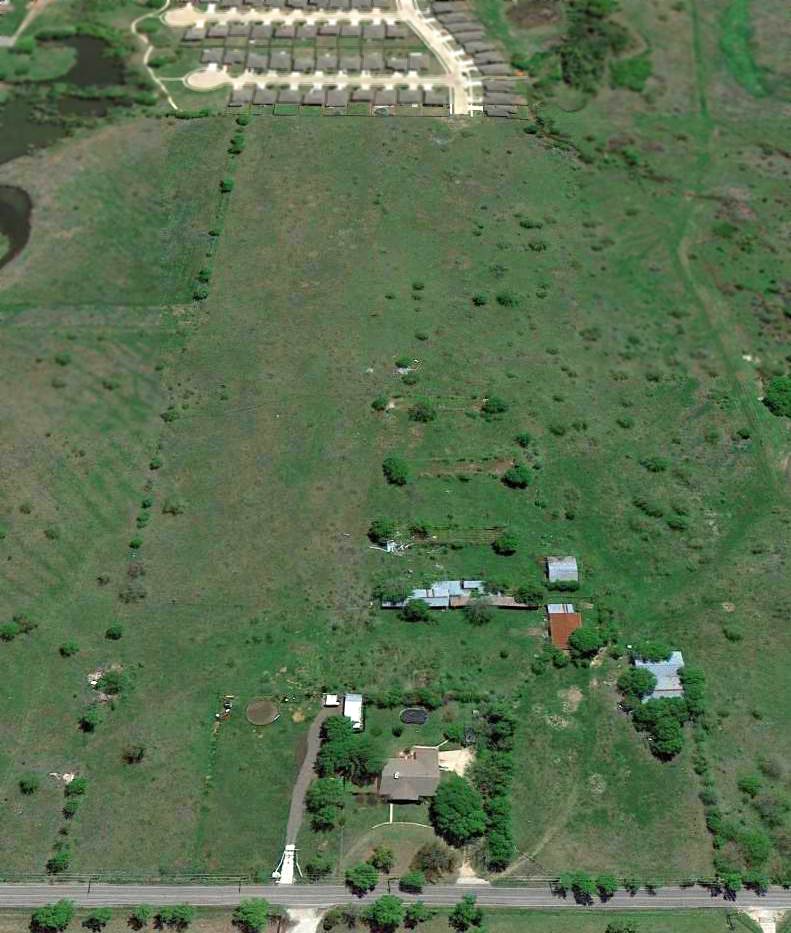

An undated aerial view looking southwest at Saginaw Airport, © 1995 Walter P. Shiel, used by permission, all other rights reserved.

For more information: http://www.cessnawarbirds.com/articles/

A 2001 aerial photo of Saginaw Airport, showing the field intact though devoid of aircraft.

A 3/15/02 aerial photo showed 2 light aircraft parked outside at Saginaw.

Steve Thomas recalled, “My acquaintance with Saginaw goes back to July 2002.

I purchased a 1962 Piper Colt N5521Z located at Saginaw.

It took us 2 days of flying to get her to its new home at Hampton Roads Executive Airport in Portsmouth, VA.”

An 8/02 photo by Paul Freeman, looking north along Saginaw's Runway 36,

less than 2 months before the airport was closed.

Paul Freeman visited Saginaw Airport in August 2002 (unaware that the field would be closed in a mere 2 months).

It was a sad sight - obvious that the field was on its last legs.

Although all of the T-hangars appeared to be occupied by light aircraft,

there were no transient aircraft, and the office was locked tight.

Furthermore, there was hardly any street sign to indicate to passers-by that an airport was operating.

How is the general aviation industry & community going to survive

if we don't do a satisfactory job of bringing in new customers?

I drove up & down the length of the runway, poked around the hangars,

and the only person I saw on the field was a nice "old-timer",

who told me that plans had already been drawn up by the local government

to subdivide the airport property into plots for new houses.

An 8/02 photo by Paul Freeman of the T-hangars along the west side of Saginaw Airport.

An 8/02 photo by Paul Freeman of the office & main hangar at Saginaw Airport.

Steve Thomas recalled, “I just so happened to be in the area again in late September 2002

and made a point to stop by once more this time by car.

A sad sight as no one was around & some of the hangars were already empty.

During this visit, was unaware the place was in its final days.”

According to Michael Reddick, Saginaw Airport was closed in November 2002.

The final takeoffs were staged on the day of the closing.

Barbara Beerling, daughter of airport owner J.D. McNeill,

placed the yellow X's on the runway after the last flight out.

Saginaw was still listed in the 2003 Airport Facility Directory,

although with the remark, "Airport closed permanently."

In its last year of operation, FAA statistics listed 40 aircraft as being based on the field,

and estimated the average number of takeoffs & landings as 39 per week.

In Michael Reddick's words, "Over 50 years of aviation history & tradition

will be plowed up for the construction of more homes & apartments that some people call progress!"

A 7/6/03 aerial photo showed Saginaw's runway marked with closed-runway “X” symbols,

but the field otherwise remained intact.

A November 2004 photo by Mark Morgan, looking northeast at the abandoned hangars at Saginaw Airport… "Just rotting into the ground."

A sad sight - a November 2004 photo by Mark Morgan, looking northwest at the abandoned hangars at Saginaw Airport.

Compare to the picture from the same perspective from only 2 years ago, when all of those hangars were filled with small planes.

A 1/2/05 aerial photo showed Saginaw's hangars remained intact,

but new streets & residential construction had covered the northeastern half of the property.

An April 2005 photo by Brian Goad – a sad view looking north along the former Saginaw runway.

The asphalt runway surface has been removed, along with 3 T-hangars.

“The shop, larger hangar, and office still remain.

Note the encroaching new homes to the northeast.”

An April 2005 photo by Brian Goad, looking northwest from the south end of the former runway.

The open T-hangars on west side are gone, and a single stall hangar remains.

A June 2005 aerial view by Brian Goad, looking northwest at the former Saginaw Airport,

taken from an O-2A on final approach into Meacham Field.

The 3 T-hangars north of the main hangar had already been removed,

with houses built just to the east.

A 6/27/05 aerial photo showed the T-hangars had been removed.

A circa 2010 aerial view looking east at the remaining hangars at the site of Saginaw Airport.

A May 2011 photo by Michael Sellers looking northeast at the start of demolition of the remaining structures at Saginaw Airport.

Michael reported, “This morning I noticed they were beginning tear-down on the last remaining structures.”

A May 2011 photo by Michael Sellers looking north along the former Saginaw runway.

Michael reported, “You can still make out the faint outline of where the runway & turn-around once was.

I haven't heard anything about what is happening to the property.

But, with all of the development going on around here, I'm guessing someone bought it to build a new subdivision on. Time will tell.”

An August 2011 photo by Pete Charlton of the main Saginaw hangar.

Pete Charlton observed in August 2011, “Things change around us in the blink of an eye.

Last July I was headed into Saginaw to have breakfast at JR's.

The sun was in my eyes, and as I moved east on McLeroy past Knowles Street I sensed something was different at the old airport.

Something was missing. Something was new.

What was missing was the older yellow brick house, its garage & the outbuildings around what had been the airport center.

In the space of a week, everything was changed. What was new was the hangar.

Not really new, but you never could really see it before because of the clutter.

It struck me as impressive, in a way. I stopped & pulled into the driveway for some pictures.”

Pete continued, “I have lived west of Saginaw since about 1997 and am into & out of the town several times a week, sometimes several times a day.

The land had been sold for development several years ago.

The paved runway had been plowed up & the T-hangars on both sides had been taken down with one exception.

Now on this day there is just the big hangar. However, that hangar took on a whole new dimension without the clutter around it.

The place almost becomes an Aerodrome in the classic sense. Built of common materials it still becomes a little stately in its appearance.

Solid. It has seen the best & worst of aircraft and probably some that were unique or improbable.

Just picture a stagger-wing Model 17 Beechcraft in front of it, or a big radial-engined Cessna 195.”

Pete continued, “I talked to the man who rents the hangar & he told me he thought the owner had the rest of the buildings pulled down & plowed under

because they were in bad shape & there were some liability problems.

He said he had no idea of what was in the future for the old hangar, but that it was serving his purposes nicely.

I suppose it it hopeless to think that someone might come up with some way to save the big old hangar & use it without too much change.

At 65+ years old it could be considered historic in a technical sense,

but I have an idea that the land is probably zoned commercial & if the economy ever turns around, then we'll see it disappear overnight as well.”

An August 2011 photo by Pete Charlton of a shed hangar which remains at Saginaw.

Pete observed, “There is one old building remaining to the west of the big hangar.

It's a closed shed hangar that has been used occasionally for 'estate sales', but everything else around it is gone.”

A 4/10/13 aerial view looking north at the remains of Saginaw Airport: 2 hangars, foundations, and most of the length of the formerly-paved runway.

Thanks to Mark Robinson for pointing out this field.

____________________________________________________

Oliver Farm Airport (04TX), Saginaw, TX

32.87, -97.4 (Northwest of Fort Worth, TX)

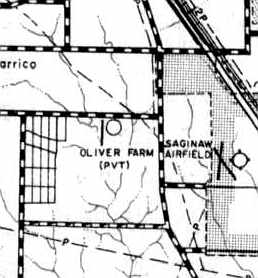

Oliver Farm Airport (as well as the nearby Saginaw Airport),

as depicted on the 1963 Tarrant County TX Highway Department Map (courtesy of Gainey Bradfield).

Oliver Farm Airport was one of 4 airfields which were once located

in a space of only 4 miles from east to west just to the northwest of Fort Worth.

Oliver Farm Airport was evidently established at some point in 1963,

as it was not yet depicted on a 1963 aerial photo.

The earliest depiction of Oliver Farm Airport which has been located

was on 1963 Tarrant County TX Highway Department Map (courtesy of Gainey Bradfield).

It depicted the field as having a single north/south runway.

Inexplicably, Oliver Farm Airport was not depicted at all on the 1966 DFW Local Aeronautical Chart.

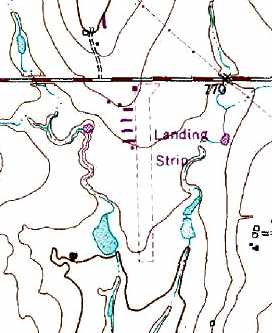

The 1969 USGS topo map depicted a single unpaved north/south runway, labeled simply as “Landing Strip”,

with a few small buildings along the northwest side.

Colin Anderson recalled, “Oliver Farm Airport... I soloed from that airport in June 1969

and subsequently got my private certificate in the following August (we had only 1,800' at that time).

I became friends with Red Oliver who owned the airport & built it for his son Richard.

We did lots of goofy things (though they seemed OK at the time).

I had great times there & we had interesting happenings such as an FAA inspector crashing his plane (Stinson)

at the end of the runway after running out of gas.

Lots of people learned to fly there. We used to shoot jack rabbits there at night & often hunted doves during the day.”

The earliest photo which has been located of the Oliver Farms Airfield was a 1970 aerial view.

It depicted the field as having a single unpaved north/south runway,

with 4 hangars on the northwest side of the field.

Jack Coats recalled, “Oliver Farm... I got my license flying from there in spring of 1970.

I rented a Cessna 150 there wet for $10/hour, and used it in instruction I took from a DFW Center Air Traffic Controller that 'relaxed' by training beginning pilots.

I was also in CAP, and flew the 150 with extended tanks (they could last 10 hours, but my bladder never could!),

an L4 (military Piper Cub with extended 'hat rack' to allow carrying a stretcher behind a pilot in the front seat), and a rebuilt CAP Funk aircraft from there.

Parachuters use the field too. The south end of the runway had a single-strand electric wire (I took out multiple times, by accident, landing too short)

and a barbed-wire fence (normal height, about chest high) on the North end. I was afraid of it & the power lines across the street!

One minor oddity, was that ALL traffic circled ONLY to the East.

Of you went to the West, you were in the controlled flight path of Carswell AFB.”

The earliest aeronautical chart depiction which has been located of the Oliver Farms Airfield was on the July 1976 DFW Terminal Chart (courtesy of Jim Hackman),

which depicted “Oliver” as having a private airfield with a 2,200' unpaved runway.

The last aeronautical chart depiction which has been located of the Oliver Farms Airfield was on the 1978 DFW Sectional Chart.

It depicted “Oliver” as a private airfield having a 2,200' unpaved runway,

and indicated that the field conducted glider operations.

Oliver Farm Airport was described in the 1982 AOPA Airports USA Directory (courtesy of Ed Drury)

as having a single 2,200' turf Runway 17/35.

The field was said to offer fuel, minor repairs, hangars, tiedowns, flight instruction, and plane rental.

Paradoxically, in spite of the above services, the field was described as “Private, use at own risk.”

The operator was listed as Oliver Farm Airport.

The 1982 USGS topo map depicted Oliver Farm Airport as consisting of a single 2,300' unpaved runway,

with a cluster of hangars along the northwest side.

The field was labeled merely as “Landing Strip”.

Brian Goad recalled, “Dad originally had a PT-23 at Oliver Farms from about early 1985

until March 6, 1987 when he lost a jug over Arlington & had to make an emergency landing in the UTA soccer field.

The PT-23 was damaged beyond repair, but dad came out with only a few cuts & stitches.

Then about mid 1988 dad got the L-4 & kept it at Oak Grove for a short time.

The L-4 ended up at the farm for a short time,

and in late 1989 we moved it over to Saginaw.”

Christina Williams recalled, “ My grandfather, James 'Nat' Summers used to own Oliver Farm in the 1980s.

He changed the name to Summers Family Airport & my parents (Joe & Beverly Clay)

moved us to live there when my brother & I were very small children.

My dad was a pilot, flight instructor, aircraft mechanic & he also ran the gas pump (jack of all trades).

My mom made sure the light bulbs on the turf runway were replaced as needed among other duties.

I remember people from all over the world coming to Fort Worth to earn flight hours because it was cheaper in the US than most countries to do so.

I remember Richard Barrett, who was one of my dad’s best friends at the time.

Those years in Fort Worth on the family airport hold some of my family’s fondest memories.”

A circa 1988 photo of Brian Goad flying his father's L-4

at Oliver Farm Airport's “Last First Annual Bash”, a few months before its closing.

Brian Goad recalled, “Oliver Farms was simply a cow pasture with open T-hangars.

I remember the first time I took my ex-wife there for her first flight in the L-4.

We turned off the road, opened the gate, drove south on the grass strip (cow pasture),

and Brenda could see the planes in the hangars,

but turned & asked 'Where is the runway?' I said 'We’re on it.' Her eyes got a little wide.

I told her to watch her step when she gets out, because I didn’t want any cow #### in the plane.

I drive a little further & she sees the L-4 & says 'Oh, now that’s a cute little plane.'

I replied, 'Yep, and you’re gonna fly in it today.'

And with even wider eyes, her response was 'OH!'

She freaked out when I didn’t close the window or door for the flight, but ended up loving it.”

Brian continued, “I remember the 'Last First Annual Bash' we had out at the farm.

Many planes flew in, we had a big cook out, spot landing contest, and played silly aviation games.

One in particular was where teams of 2 people would take a bed sheet out on the strip,

and the guys in the L-birds & Cubs would fly over & drop eggs

while the teams tried to catch the eggs in the sheets without breaking them.

We had cheaters in the planes, they didn’t just drop the eggs, they threw them at times.

My best friend brought his radio controlled L-4 (modeled after our L-4) and actually flew it in formation with the real L-4.

A real crowd pleaser.”

Brian continued, “After looking at dad’s log book, I just remembered that Oliver Farms was also called Summers.

I remember the change, but don’t know why.”

The date of closing of Oliver Farm Airport has not been determined.

It was no longer depicted on the 1998 Sectional Chart.

As seen in the 2001 USGS aerial photo, Oliver Farms Airport remained completely intact.

A circa 2002-2005 aerial view looking north at the former hangars of Oliver Farms,

with the former runway area to the east.

A 1/2/05 aerial view showed Oliver Farm Airport remained intact, though deteriorated.

A 6/27/05 aerial view showed new streets & residential construction covering the southern half of the Oliver Farm runway site.

A 4/4/12 aerial view showed the 4 rows of T-hangars remained intact at the site of Oliver Farm Airport.

A 6/27/05 aerial view showed new streets & residential construction covering the southern half of the Oliver Farm runway site.

A 4/10/13 aerial view looking south at the site of Oliver Farm Airport

showed 3 of the 4 rows of T-hangars had been removed.

Oliver Farm Airport is located southwest of the intersection of North Old Decatur Road & WJ Boaz Road.

____________________________________________________

Taliaferro Field #1 / Hicks Field, Fort Worth, TX

32.91, -97.4 (North of Downtown Fort Worth, TX)

An undated (WW1 era) aerial view looking north at Taliaferro Field (from the Benbrook TX Public Library, via Corky Baird),

showing an amazing lineup of no less than 19 hangars.

This property was originally part of the Hicks Ranch, owned by Charles Hicks.

According to Bill Morris, “When the U.S. entered World War I on 4/6/17, the war in Europe was in its 32nd month.

The Aviation Section of the U.S. Army Signal Corps consisted of 5 'combat' squadrons with 55 serviceable airplanes.

Three of the squadrons were in the Philippines, Hawaii, and the Panama Canal Zone.

At a meeting in Washington DC in May 1917, the Royal Flying Corps Canada agreed to immediately begin training 300 pilots

and enough ground support personnel to organize 10 squadrons for the US Army Air Service.

In return, the US Army would construct a site in the US for RFC Canada to use for training during the winter months.”

Bill continued, “In June, the War Department inspected 6 sites around Fort Worth which had been offered by the Chamber of Commerce

and by July, RFC Canada inspected five potential sites in Texas & Louisiana for use during the winter.

In August, the War Department signed leases on 3 sites around Fort Worth & construction began in late August & early September.”

Bill continued, “The three flying fields around Fort Worth were locally referred to as Hicks, Everman, and Benbrook based on their locations.

In September 1917, the Army initially named the fields Jarvis (Hicks), Edwards (Everman), and Taliaferro (Benbrook).

When RFC Canada selected the 3 fields around Fort Worth,

the Army established Camp Taliaferro in Fort Worth to direct the activities of the 3 fields

and designated them Taliaferro Field #1 (Hicks), Taliaferro Field #2 (Everman) and Taliaferro Field #3 (Benbrook).

The Camp Taliaferro offices for the U.S. Army Air Service & RFC Canada were initially located in the basement of the Chamber of Commerce building

to handle pay, purchasing, and administrative services for their own personnel assigned at the 3 fields.”

Bill continued, “Work on constructing the airfield had to be done fast.

Cattle were moved out, and construction crews worked feverishly at the site.

U.S. Army Air Service squadrons which had been training in Canada began arriving in October 1917.

The Royal Flying Corps squadrons arrived on 11/18/17.

The first training flights occurred on November 19.”

Bill continued, “The first winter was difficult. Many men lived in tents in this snowy winter.

During the winter of 1917-1918, there were 8 deaths due to influenza at the 3 flying fields.

Between November 1917 - April 1918, 39 RFC personnel died as the result of aircraft accidents, influenza, or other illnesses at the 3 flying fields.”

Colonel David Roscoe, the U.S. Army Air Service commander at Camp Taliaferro in Fort Worth

who directed the Air Service activities at the 3 flying fields

recalled that "...a plane landed here every 34 seconds from dawn until dark,

and during the course of a day the average number of hours flown by instructors & and cadets was 1,300."

With that amount of flying activity, accidents were common.

Although there were serious crashes, many of them resulted in little injury to the pilot or gunner.

According to Bill Morris, “Following the departure of the Royal Air Force in April 1918,

Camp Taliaferro was closed & each of the 3 fields operated as separate sites.

On 4/16/18, the fields were formally renamed Taliaferro Field (Hicks), Barron Field (Everman) and Carruthers Field (Benbrook).”

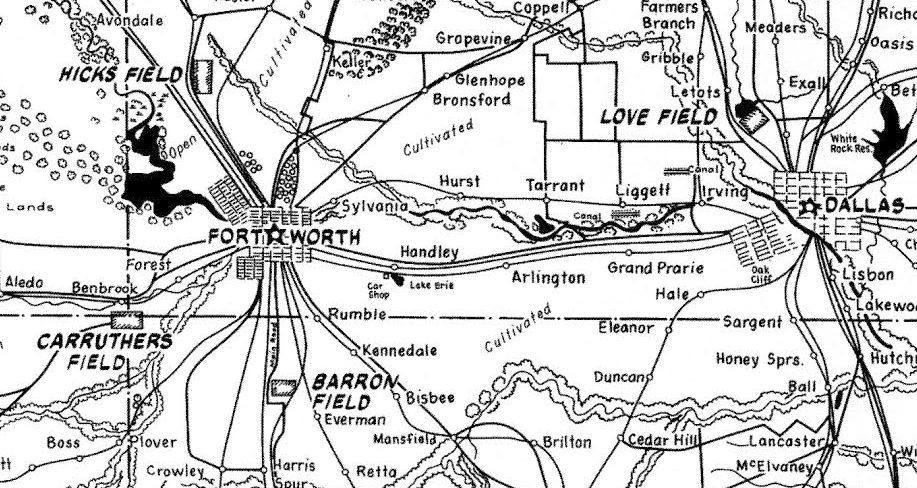

An undated (WW1 era) map hand-drawn by Gus Benneke for the WW1 pilot trainees out of Love Field

who used the 3 Taliaferro Fields (from The Frontiers of Flight Museum, courtesy of Knox Bishop).

Bill continued, “The three airfields around Fort Worth were part of a larger effort to increase pilot training for the US Army Air Service.

Barron Field & Carruthers Field were 2 of the 14 newly-constructed primary pilot training fields.

Taliaferro Field was the first of 4 aerial gunnery schools established by the Air Service

and relied heavily on the RFC Canada School of Aerial Gunnery to get their gunnery training program 'off the ground'.”

An undated photo of a SPAD XIII biplane at Taliaferro Field (from the Benbrook TX Public Library, via Corky Baird).

An undated photo of a Curtiss JN-4 biplane at Taliaferro Field (from the Benbrook TX Public Library, via Corky Baird).

The biplane of choice was the JN-4 "Jenny".

It had 2 open cockpits; the student manned the front, and instructor commanded from the rear.

With the Curtiss OX-5 engine, it could reach a top speed of 64 MPH.

Later Jennys were powered by the 180 HP "Hisso" engine, which increased it's speed to 78 MPH.

There were 2 versions of the Jennys flown at Taliaferro & the 2 other flying fields.

The Canadian version was called the JN-4 (Can) Jenny "Canuck"; the American version was the JN-4D.

According to Bill Morris, “When the RFC Canada arrived in Fort Worth in November 1917,

they brought 254 JN-4 (Can) aircraft with them for training at the 3 fields around Fort Worth.

When they returned to Canada in April 1918, they turned over 180 serviceable aircraft to the U.S. Army Air Service.

By then, Curtiss & license-built JN-4s were keeping up with demand.

Training was initially conducted by the Canadians. The 2 fields at Everman & Benbrook were in charge of primary flight training.”

Bill continued, “Taliaferro Field was the first of 4 aerial gunnery schools operated by the U.S. Army Air Service

and relied heavily on the RFC Canada School of Aerial Gunnery to establish the training program.

By early 1918, an 11,700-acre aerial gunnery range was operating just to the west of Taliaferro Field

and included 3 machine gun firing ranges, a series of floating targets on several ponds on the site as well as water-filled airplane & trench system targets.”

Pilots came from all over the U.S. to learn this new art, including 300 ensigns from the U.S. Navy.

Gunnery was taught in a 6 week course, on the ground in special gunnery ranges & in the air - in the reliable Jenny.

One of the first gun cameras were developed at this time.

This allowed an evaluation of the cadets accuracy - without firing a live round.

Pilots were taught how to fire from the pilots cockpit as well as the gunners cockpit.

The gunners cockpit did not have a seat, but only a crossbar to sit on.

There was not a seat belt provided, and firing the swivel-based Lewis machine gun meant standing up!

Besides molding men into lean, mean fighting machines,

Taliaferro also molded some long lasting friendships between the Canadians & Americans.

Floyd Scott, a member stationed at Taliaferro told a Fort Worth newspaper,

"One of the most vivid memories of Hicks Field

was the remarkable friendship that existed between the RFC pilots & the American flyers."

Indeed, the townspeople of the surrounding communities opened their homes,

their hearts & numerous facilities to the young aviators.

With their training behind them, the aviators were to test their skills in battle.

The first to leave was the 17th Aero Squadron, with 95 pilots & a full compliment of support officers & enlisted men.

They departed Fort Worth on 12/17/17.

In January, 1918 the 22nd, 27th & 28th Aero Squadrons left for France.

A month later, the 139th, 147th & 148th left to amass our fighting forces.

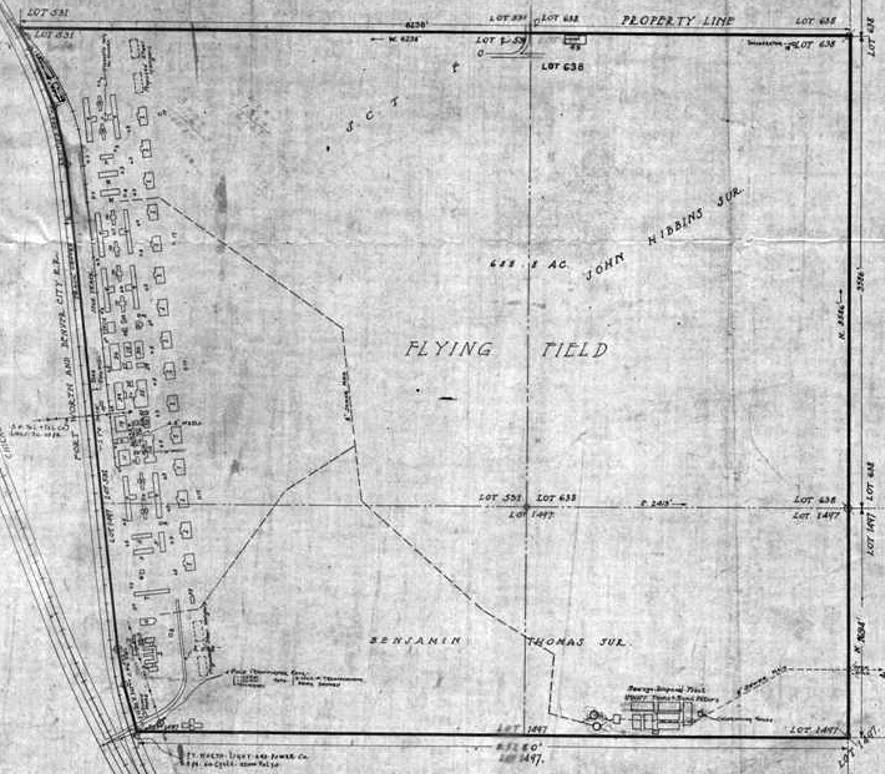

An early 1918 US Army Signal Corps Supply Division property area map (courtesy of Bill Morris)

showed Taliaferro Fields #1, #2, #3, and the original aerial gunnery school target range.

An early 1918 US Army Signal Corps Supply Division property map of Taliaferro Field #1 (courtesy of Bill Morris).

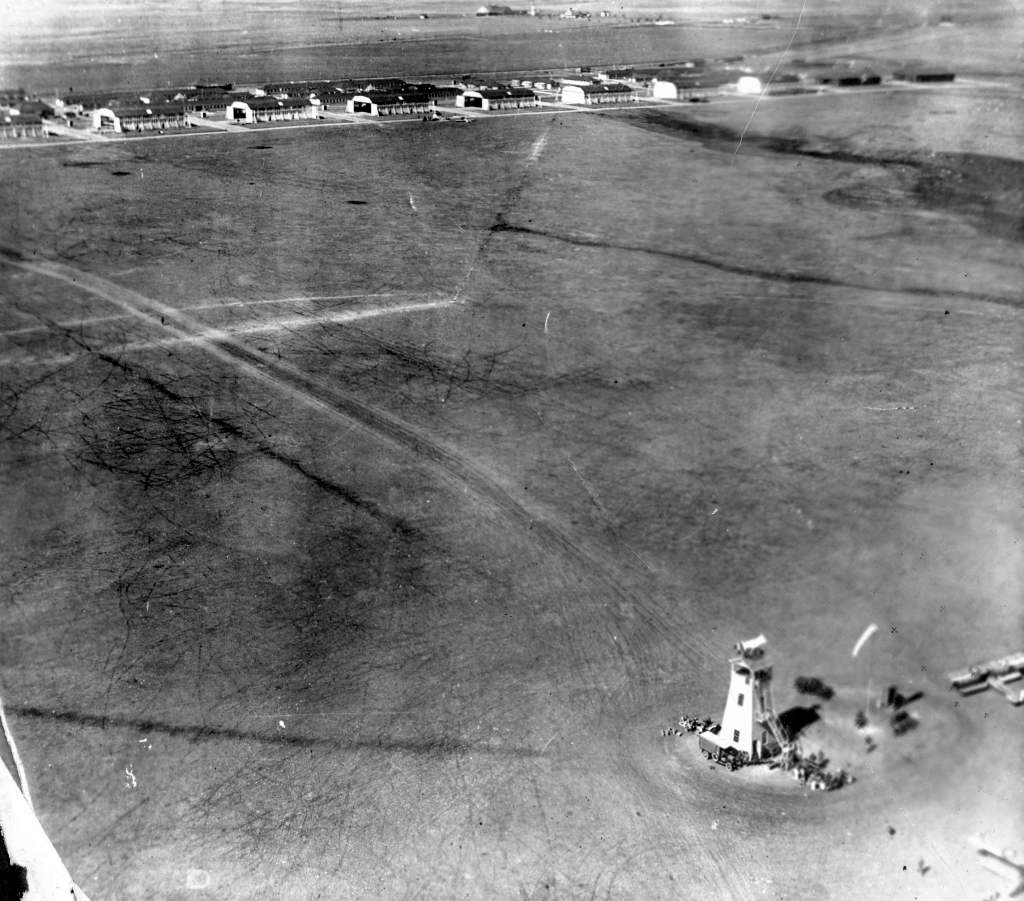

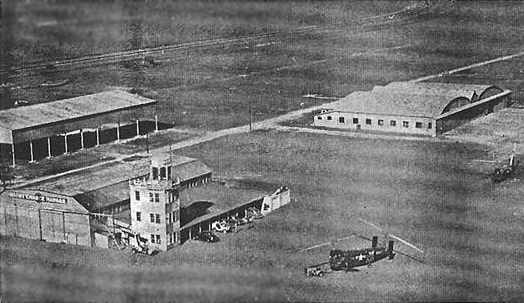

A WW1 era aerial view of the control tower, flying field, and hangars at Hicks Field. (from the Benbrook TX Public Library, via Corky Baird).

In April of 1918, the Canadians packed up to return to Canada.

They had accumulated over 67,000 flying hours, trained 1,960 pilots, 69 ground officers & 4,150 men in various ground skills.

To the whine of their own bagpipe band, a sound foreign in the land of cowboys & cattle,

they marched past many of their cheering Texas friends & took their departure at the T&P Railroad Station in downtown Fort Worth.

According to Cathie Jarvis, “An ancestor (Herbert Huck)

was killed in an air accident at Taliaferro Field on September 27, 1918.”

On 11/11/1918 came news of peace. World War I was over. The men at Taliaferro rejoiced.

One cadet, Mr. Jack Jaynes, was both elated & frustrated.

He would not be able to prove his newfound training to Uncle Sam - his chance had vanished.

But all was not lost! He & some fellow aviators felt that something spectacular was in order.

They decided to honor the occasion with a never-to-be-forgotten air show directly into the downtown area of Fort Worth.

They simulated street strafing down the avenues & between the buildings.

The width of their wings often caused them to turn or bank sharply to avoid hitting the buildings.

Everyone who witnessed this talent of flying skills would never forget it!

Jack Daley said of Taliaferro, "Much of the ramp was grass with some rolled oiled rock base near the main group of hangars.

The tie downs were made from old coffee & oil cans, used as cement molds with the D-rings inserted in them.

I dug one up & the can was an "Archer Av Oil " container.

I once ran into an old timer that had trained at the field when it was [used by] the Royal Flying Corps in WW1.”

In 1919, with news of the Armistice, Taliaferro Field was deactivated.

The hangar doors were closed on an unforgettable episode in the history of American military aviation,

and the chapter on WW I was closed.

But the chapter wasn't closed on Taliaferro Field.

Taliaferro Field remained dormant for a time, and the remaining structures tried to stand their ground against wind & sun.

Cattle roamed the areas where the landing field & gunnery ranges once stood.

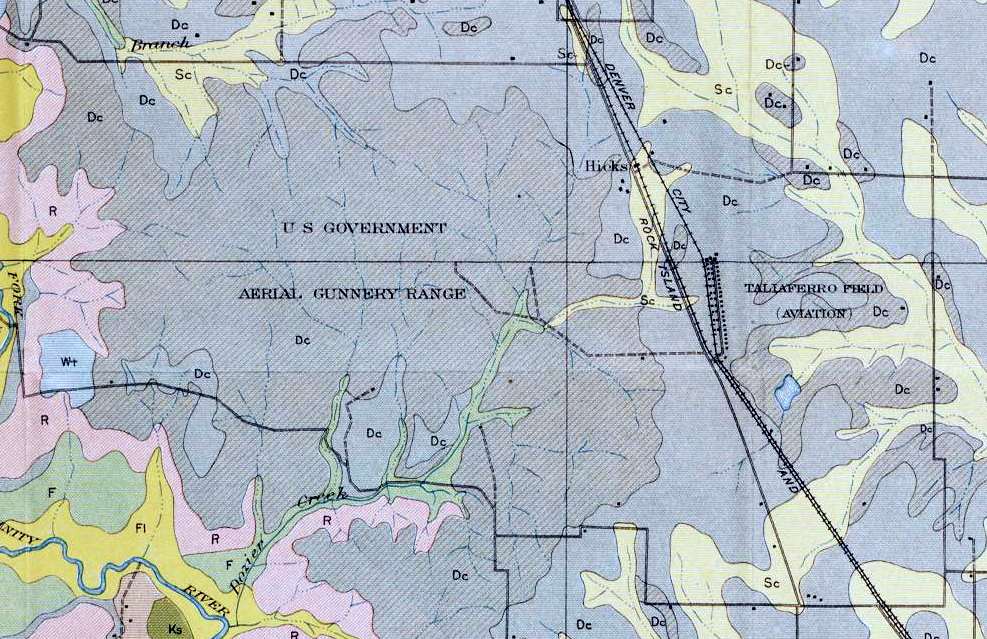

A 1920 Agriculture Department Soil Map depicted “Taliaferro Field (Aviation)” & its adjacent “US Government Aerial Gunnery Range (courtesy of Randy Gilbert).

Taliaferro Field was not depicted at all on the 1932, 1934, 1935, and 1940 Dallas Sectional Charts.

But in 1940, Europe was again at war, and Uncle Sam felt that he must be prepared.

Responding to this call, Taliaferro Field was reopened as a training base in July of 1940 & renamed Hicks Field.

A major construction & renovation job was required for Hicks,

and once completed, Texas Aviation Inc., and W.F. Long Flying School moved in.

As a private flying school, it received a contract to train new cadets on the new field that was constructed.

Thirty-eight new Fairchild PT-19s & PT-19As were assigned to Hicks,

and the Army Air Corps again had pilots training there.

Hicks was one of the first primary flying schools in the Army Air Corps expansion program.

Lt. James Price was the first commanding officer.

The instructors were all contract civilian instructors, pilots with a long history of experience in light aircraft.

They would take the cadets through the rudiments of basic flying & guide them through their first solo flights.

When successfully completed, they would go to Basic Flight Training at Randolph AFB

and then Advanced Flight Training at Foster Field.

The original WW1-era hangars were evidently replaced at this time by larger twin-arch hangars,

and a 4-story control tower was constructed in front of one of the hangars.

According to Bill Morris, “Most of the World War I hangars & buildings were gone at this time - salvaged for the lumber.

Construction of each World War I field required about 4 million feet of lumber.

There were at least 2 World War I hangars still on the site, including a number of other buildings.

The control tower was added to one of the World War I hangars.”

This activity did not escape the eyes of the old aviators from WWI,

still residing in Fort Worth & surrounding towns.

They felt a certain responsibility to the new cadets at their own flying field.

The World War Flyers, as the 43 old timers came to be known,

sent a letter to the parents of each new cadet coming into Hicks Field.

The letter assured the relatives that they would do everything possible to make the lad welcome & happy in Fort Worth.

Each class was given a formal introduction to Fort Worth,

and introduced them to the prettiest girls at a dinner dance at the River Crest Country Club, one of the finest in the City.

This came to be a tradition on the first Saturday night of the month when cadets were permitted to leave their post.

This successful program greatly boosted morale.

Jimmie Wooten recalled, “My family lived on Hicks Field from sometime in the 1940s until we moved to Lufkin in 1949.

My dad, also named Jimmie Wooten, was a flight instructor for the CPT program from 1940.

I am not sure what all he did at Hicks, but I know that he flew & I remember something about him being a manager of the field.

I was just a little kid, having been born in 1941, so my memories are somewhat vague.

I was also cautioned not to go playing in the hangars, as the mechanics didn't want to have to worry about a little kid roaming around.

Our 'home' was the abandoned infirmary with tar paper siding & corrugated iron roof, that leaked profusely when it rained.

I would get pots & pans from the kitchen & put them under the drips. I would then ride my tricycle through the puddles & track up the floor.

It was hot in the summer & cold in the winter. One winter, the goldfish froze in his bowl inside the building.

I remember living there when there was an armed guard at the gate to the field, although his arm may have been a .22 revolver.

There was another family, Garza Wooton (spelled differently) who lived there also.”

A June 1941 photo of PT-19 trainers in front of the Hicks Field hangars (from the West Sanders Collection, via Bill Morris)

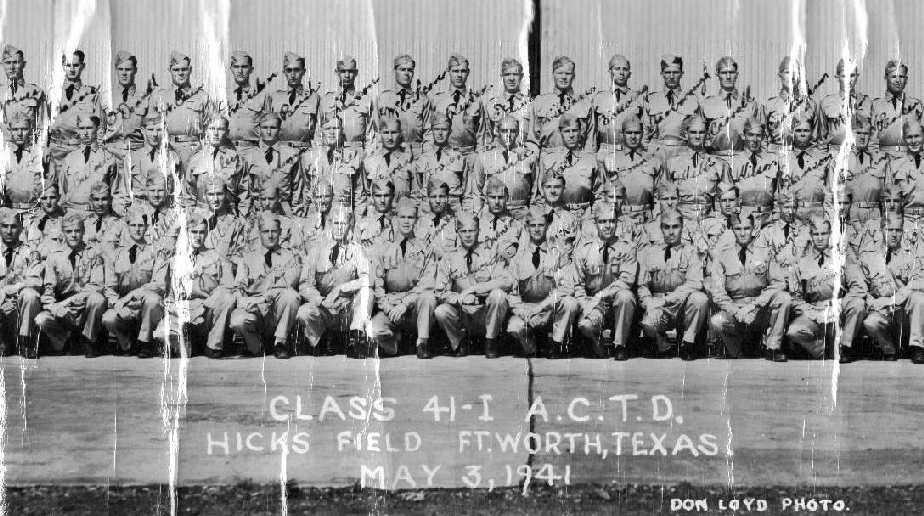

A 10-week course of primary training continued at Hicks,

and a total of 2,403 cadets were processed, and about 70% made it to the next level of training at one of the Army Air Corps basic flying training fields.

Class 41-I from Hicks Field (courtesy of Robert Burton, whose stepfather, Colonel William Calhoun,

graduated in class 41-I from Hicks Field & went on to become a decorated veteran of the mighty 8th AF during WW2).

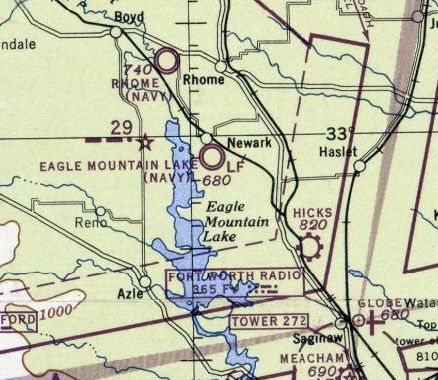

The earliest aeronautical chart depiction which has been located of Hicks Field was on the August 1941 Dallas Sectional Chart,

which depicted Hicks as a military airfield.

Hicks Field was depicted as a commercial airfield on the 1942 Dallas Sectional Chart (according to Chris Kennedy).

Richard Taylor recalled, “There was no paved runway at Hicks Field in 1942 when I took Primary training there.

I was in the class of 43 D & soloed at one of the fields a short distance from Hicks Field.

From there most of us went to Goodfellow Field for basic training.”

A World War II era aerial view looking north at a snowy Hicks Field (from the Ben Guttery Collection, via Bill Morris).

Bill Morris observed, the photo showed “the 3 double-arch steel hangars & parking apron, student barracks, classrooms, mess hall and other buildings to support the pilot training program.

The 2 remaining World War I hangars are also on the site.”

A 10/15/43 aerial view looking west from the 1945 AAF Airfield Directory (courtesy of Scott Murdock)

depicted Hicks Field as an open grass area with a row of hangars along the west side.

The March 1944 Dallas Sectional Chart depicted Hicks as a commercial/municipal airport.

By 1944 Hicks Field had deactivated its training schools.

The 1945 AAF Airfield Directory (courtesy of Scott Murdock) described Hicks Field

as a 426 acre irregularly-shaped property within which was a 2,700' square sod all-way field.

The field was said to be owned by private interests, but to be operated by the Reconstruction Finance Corporation.

Bill Morris added that the RFC operated the field “to sell surplus military aircraft”.

By 1945 Hicks was being used as a civil field.

Jimmie Wooten recalled, “The field was used for storing airplanes after WW2 ended,

and since there were no other kids my age on the base, I would climb in a plane, put on a headset, flip switches, and pretend to fly the plane.

At one time, a fire was set by railroad workers burning off the grass along the tracks. The fire swept the field, exploding remaining fumes in the plane's gas tanks.

It was a sad day when the crane arrived & started smashing the airplanes flat & loading them onto flat rail cars for sale as scrap.

Engines & radios were pulled first, and maybe instrument panels, but that was all that was salvaged intact.

The fire destroyed a large building that was being used to store hay. It made quite an inferno.

I remember the name Henry Seale as owning some or all of the surplus aircraft.

I saw my first helicopter at Hicks. Someone flew one in & demonstrated that it could go up & down & sideways & forward.”

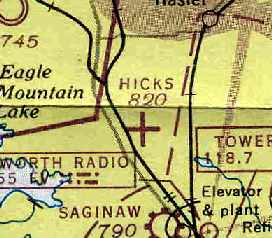

The last aeronautical chart depiction which has been located of Hicks Field

was on the March 1947 Dallas Sectional Chart (courtesy of Chris Kennedy).

It depicted Hicks as an auxiliary airfield.

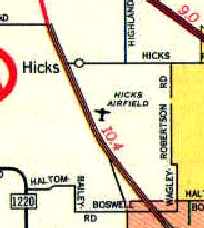

The 1948 USAF Urban Area Chart depicted Hicks Airfield as an irregularly-shaped outline, with a road & several buildings on the west side.

A circa 1952-53 aerial view looking southwest at the Hicks Field hangars (courtesy of Ned Gilliand),

taken just before Bell Helicopter began their use of the facility.

Note the deteriorated carcasses of what appear to be several Cessna AT-17 Bobcats in the foreground.

A 1/4/53 USGS aerial view showed Hicks Field to remain intact.

A undated aerial view looking at the Hicks Field control tower & hangars,

from the 1/1/54 issue of the Bell Aircraft Helicopter Division News (courtesy of Ned Gilliand).

The original caption read, “Powerful Navy HSL-1 helicopters roost at Bell's Hick Field facility

located 23 miles from Hurst Plant on TX Highway 287.

Flight test maintenance & inspections are carried on in 11,000 square-foot hangar by 114 Hicks Field employees.”

Ned Gilliand recalled, “The HSL-1 (Bell Model 61) was designed in the Bell Aircraft plant in Niagara Falls, NY in 1950-51.

The prototypes (XHSL-1's) were built there

and sent to Bell's new Fort Worth helicopter facility by rail in late 1951 or 1952.

The Navy, requesting a remote facility to work on this new anti-sub helicopter,

worked to get such a place, and Hicks was the result.

This outlying facility was ideal due to the noise of the large R-2800 engines in the XHSL helicopters,

and also it was close to Eagle Mountain Lake, where then-classified sonar dipping was developed for this ship.

The Hicks Field facility was used by Bell Helicopter in 1954 & perhaps early 1955

to do experimental flight test work on Bell’s Model 61 XHSL-1 tandem rotor helicopter for the US Navy.”

A 1954 photo looking west/northwest at a Bell XHSL-1 in front of the Hicks Field control tower & hangar (courtesy of Ned Gilliand).

The hangar adjacent to the control tower was a WW1-era hangar,

older than the other twin-arch-roof hangars constructed at Hicks during the WW2 era.

A 1954 photo looking southwest from near the Hicks Field control tower toward 2 Bell XHSL-1s,

with a Bell 47 hovering the the background (courtesy of Ned Gilliand).

Ned Gilliand recalled, “The production HSL-1s were manufactured at the Hurst Plant #1,

while most of the experimental operations remained at Hicks, and afterwards, briefly at the Globe plant.”

According to Ned Gilliand, “Around the time Bell left the facility [mid 1950s],

the control tower & adjacent wood hangar burned to the ground,

leaving only the metal & concrete hangars.”

After Bell left, the field was mostly used as a general aviation field by civilians.

The 1955 USGS topo map depicted Hicks Field as an open area without any runways,

but with a cluster of buildings along the west side.

A 1956 aerial view did not show any aircraft on Hicks Field.

A 1963 aerial view showed the grass airfield area remained clear,

but there was no indication of any aviation use.

Hicks had fallen into disuse by the 1960s, when it was no longer depicted on the USGS topo map,

and only a few businesses remained in the area.

It was not depicted at all (even as an abandoned airfield)

on the 1963 Tarrant County TX Highway Department Map (courtesy of Gainey Bradfield)

or the 1964 DFW Sectional Chart (courtesy of Ross Richardson).

The 1969 USGS topo map still labeled the site as Hicks Field,

but also depicted several small buildings that had been constructed over the airfield area.

A 1970 aerial view showed that the Hicks Field property had begun to be used for industrial purposes,

with several buildings having been added over the former airfield area.

The 1974 USGS topo map still labeled the site as Hicks Field,

but also depicted several more buildings that had been constructed over the airfield area.

Hicks Airfield was still depicted on the 1979 AAA DFW road map, even though it had evidently ceased to function as an airport by this point.

A 1981 photo by Bob Adams (courtesy of Bill Morris) of the sole-remaining World War I hangar being disassembled at Hicks Field.

It was moved to the Southwest Aerospace Museum outside the entrance to the General Dynamics plant.

According to Bill Morris, “When the museum folded, the hangar pieces were bulldozed into a large pit & buried.”

The 1982 USGS topo map no longer labeled the site as Hicks Field.

In 1985 a modern general aviation airport named "Hicks Airport"

was built on a separate plot of land one mile to the north-northwest of the original Hicks Field.

By the early 1990s, the area of the original Hicks Field was being used for various industrial purposes.

Jack Daley said of Hicks, “My ex & several of her family members were employed

at the old Fleetform boat manufacturing company located

in one of the former flight office & squadron office buildings just to the left,

as you come into the field, and about opposite the hangar complex.”

By the late 1990s the site of the Hicks Field Sewer Corporation

(which had provided sewer services for industrial facilities at Hicks Field)

was the focus of an investigation for environmental cleanup by the Texas Superfund.

A 1994 photo by Scott Murdock of the WW2-era hangars at the original Hicks Field.

A 1994 photo by Scott Murdock of the WW2-era hangars at the original Hicks Field.

A 1995 USGS aerial photo showed several WW2-era hangars still remained along the west side of the Hicks Field site,

but several buildings & roads had been built over the airfield area.

A close-up from the 2001 USGS aerial photo,

showing 2 of the 3 WW2-era hangars which remain standing at the site of Hicks Field.

Ned Gilliand reported of the former control tower & adjacent wood hangar (which had burned down in the 1950s),

“When I was out there in 2002, the slab was all that was left,

and it was pretty well damaged, probably from the heat of the fire.”

Scott Murdock reported in 2005, “I paid a return visit to Hicks Field on 15 May 2005.

The same 3 double-hangars I noticed in 1994 were still standing.”

A 2005 photo by Deene Ogden of one of the remaining hangars at the former Hicks Field.

Deene observed, “Two of the large hangars & the land surrounding them are for sale.”

A 2005 photo by Deene Ogden of the sign for the “G.A. Fence Company, Saginaw, TX”

on one of the remaining hangars at the former Hicks Field.

A circa 2002-2005 aerial view looking west at the WW2 era hangars at the site of Hicks Field.

A 4/10/13 aerial photo showed several WW2-era hangars still remained along the west side of the Hicks Field site.

A 2013 photo by Bill Morris of the World War I ammunition magazine which still remains at the site of Taliaferro Field #1.

The site of Hicks Field is located at the intersection of Hicks Field Road & East Hicks Field Road.

See also: The Handbook of TX Online.

____________________________________________________

Taliaferro Field Bombing Target / Hicks Field Bombing Target, North Richland Hills, TX

32.917, -97.424 (North of Fort Worth, TX)

A 2006 aerial photo (courtesy of Ned Gilliand) of an odd artifact from the WW1 aviation days of Hicks Field.

Ned Gilliand reported, “Two Bell pilots found a recessed actual-sized WWI biplane silhouette west of the old Hicks Field location.

Locals say it was used for practice bombing (using bags of flour) & for some strafing practice.

Over the years the local farmers fenced in the site, hoping to protect it in some way.

The pilots used a cell phone to photograph the image from the helicopter in flight of the WWI artifact.”

Ned's source for the photo remarked, “The site is on the West side of the creek

and just on the opposite side from a new gas-well-head site on the creek.

There is a new housing addition a half mile northwest from the site

and the entrance to the housing is from Bonds Ranch Road.

The road in the photo is not for public access.”

A 2006 photo by Mark Nemier looking east at of the Hicks Field Bombing Target, “with the end of the left wing outline appearing,

the fence surrounding the site, and the gas well head in the background to the east.”

Mark Nemier visited the Hicks Field Bombing Target in 2006.

He reported, “The site is located approximately 1.22 miles west of the old hangars [at the original Hicks Field], maybe 273 degrees.

I suspect that this site will eventually be very close to the subdivision as the development in this area is spreading rapidly.

However, this is Texas & this is rattlesnake country. I was extremely cautious the entire walk.

I estimate the length of the fuselage to be approximately 20 feet, and the wingspan close to that.

The reason it has held up so long is because it is constructed of some form of concrete & the finish is very rough.

It was just a complete thrill to have this historic marker brought to our attention.

And it was even more amazing to actually find it.

I just hope we don't loose it to the sprawling urban development.

I suspect that if someone went to enough trouble to construct a welded metal fence, set in concrete, around the perimeter,

that there might be enough local interest to retain it as a landmark in the future.”

A 2006 photo by Mark Nemier of “the view across what would be the wing.”

The site of the Hicks Field Bombing Target is located approximately 0.9 mile west of Business 287,

and 0.6 mile south of West Bonds Ranch Road.

____________________________________________________

Eagle Mountain Lake Marine Corps Air Station (4TA2), Pecan Acres, TX

32.98, -97.49 (Northwest of Fort Worth, TX)

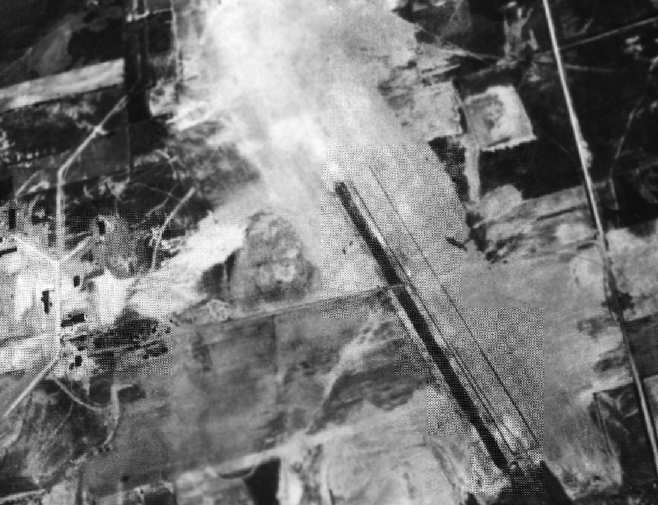

A 1943 aerial view looking south at the Eagle Mountain Lake airfield (National Archives photo).

This obscure airfield has a unique place in the Marine Corps mission

to develop what turned out to be an extremely bad idea - amphibious gliders.

That must have sounded like a good idea to someone in the middle of the Second World War, inexplicably.

In the early days of WW2, when the Marine Corps leadership considered how to carry out

the island-hopping campaign to retake numerous Pacific islands from the Japanese,

the concept of glider assaults seemed to offer promise.

A program was set up to develop amphibious gliders,

which would have a boat hull on which to land in the water,

and even have outboard motors to maneuver in the water after landing.

Four air stations were planned by the Marine Corps to train their planned glider forces.

A site on the eastern shore of Eagle Mountain Lake was selected as the site of one of those stations,

and 2,931 acres of former ranch land were purchased in 1942 to build an airfield,

with construction proceeding immediately.

MLG-71 & VML-711 arrived in late 1942 with the base's first complement of aircraft:

1 J2F Duck, 4 Pratt-Read LNE gliders, 5 Piper NEs, 2 Spartan NPs, 1 Timm N2T Tutor, and 2 Curtiss SNCs.

The station was commissioned in late 1942.

Most of the base's buildings had been completed, with the exception of the hangar.

The runways also had not been completed, so a temporary 2,700' gravel runway was provided.

Once eventually completed the airfield consisted of three 6,000' asphalt runways & a ramp on the north side.

A large number of buildings were constructed, including barracks for a total of 1,388 personnel,

and an impressive-looking 6-story control tower & operations building.

The earliest depiction which has been located of Eagle Mountain Lake MCAS was a 1943 aerial view.

It depicted the field as having 3 paved runways,

with a paved ramp with a hangar on the northeast side.

Eagle Mountain Lake MCAS was not yet depicted on the February 1943 Dallas Sectional Chart.

A 10/15/43 aerial view looking north at “Eagle Mountain Lake MCAS (Landplane)”

from the 1945 AAF Airfield Directory (courtesy of Scott Murdock).

It depicted the field as having 3 paved runways.

An undated (WW2-era) USMC photo of the impressive 6-story control tower & operations building at Eagle Mountain Lake,

which no longer stands.

A 10/26/43 aerial view looking east at “Eagle Mountain Lake MCAS (Seaplane)”

from the 1945 AAF Airfield Directory (courtesy of Scott Murdock).

It depicted a seaplane (type unidentified) in the lake offshore of the ramp.

An undated National Archives photo of one of the 2 prototypes of the XLRA-1 amphibian glider,

which was built by the Allied Aviation Corporation at the old Berliner-Joyce factory at Logan Field in Baltimore, MD.

Although not powered in the air, it had outboard motors to maneuver in the water after landing.

Allied Aviation Corporation operated from 1943-45.

An undated photo (courtesy of Bob Cannon) of one of the 2 prototypes of the Bristol XLRQ-1 amphibian glider,

which was built by Bristol Aeronautical of New Haven, CT.

Both the XLRA-1 & XLRQ-1 had a seaplane hull, carried 12 troops,

and were even intended to mount machine guns for defensive fire.

Two larger 24-seat twin-hull amphibian gliders were ordered from AGA Aviation of Willow Grove, PA

and Snead & Company of Orange, VA, but were not built.

An outlying field was built at Rhome Field to conduct initial & primary glider flight training.

Glider training was not conducted for long at Eagle Mountain Lake,

as the Marines' ill-conceived glider program was canceled in 1943,

before it could have caused any needless casualties in combat.

Following the cancellation of the Marine Corps glider program,

Eagle Mountain Lake was transferred to the Navy in 1943,

and commissioned as a Naval Air Station.

As it was adjacent to a large lake, seaplane facilities at Eagle Mountain Lake were also constructed.

They were intended to serve as a ferry stop & service facility for seaplanes flying transcontinental routes,

as well as operating the intended amphibian gliders.

The seaplane operating area was built to the west of the airfield, along the shore of the lake.

It consisted of a concrete seaplane apron, 2 ramps leading down into the lake,

and several buildings, including its own control tower just for seaplane operations.

A taxiway connected the seaplane area to Runway 12 of the airfield.

At times, up to 120 seaplanes per month passed through the Eagle Mountain Lake base.

An alternate seaplane facility was also built on 167 acres at Bridgeport Lake, 35 miles northwest.

The facilities at Bridgeport Lake were abandoned by 1944.

The Marine Corps facilities at Eagle Mountain Lake were taken over by the Strategic Tasks Air Group II from NAS Clinton, OK,

which did highly classified tests of remote controlled aircraft.

The Interstate Aircraft TDR assault drone, which was tested at Eagle Mountain Lake.

The Interstate Aircraft TDR assault drone was claimed by the Navy to be the world's first guided missile.

It carried a payload of 2,000 lbs of bombs for 300 miles,

and was used operationally in the Russell Islands in 1944.

STAG II used the facilities at Eagle Mountain Lake until being transferred to Traverse City, MI, in 1944.

At that point, the station was returned to the Marine Corps,

which recommissioned Eagle Mountain Lake as a Marine Corps Air Station.

It became the home of 2 Marine Air Groups & a helicopter squadron for the duration of the war.

A total of 84 aircraft were present on the base in 1944,

as well as a total of 2,000 personnel.

A satellite field was established for over-water bombing & gunnery training at Beaumont Airport

(10 miles SSE of Beaumont, later reused as Southeast Texas Regional Airport).

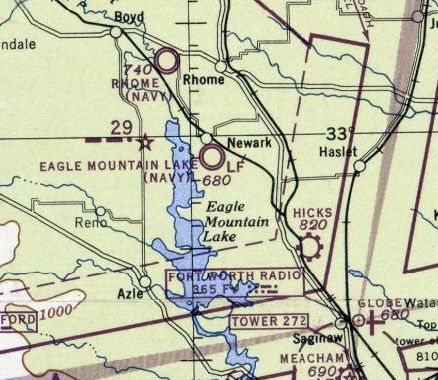

The earliest aeronautical chart depiction which has been located of Eagle Mountain Lake MCAS

was on the March 1944 Dallas Sectional Chart.

By 1945, Eagle Mountain Lake was used predominantly for night fighter training.

The primary aircraft based at the field during this period

were night fighter versions of the Grumman F6F Hellcat & F7F Tigercat.

Eagle Mountain Lake reached its maximum utilization in 1945,

with a total of 121 aircraft on board.

The Army also had a facility of the Fort Worth Quartermaster Depot at Eagle Mountain Lake,

which supported shipments from the Depot.

A 1945 photo of the seaplane ramp at Eagle Mountain Lake (National Archives photo).

The 1945 AAF Airfield Directory (courtesy of Scott Murdock) described “Eagle Mountain Lake MCAS (Landplane)”

as a 2,922 acre irregularly-shaped property having thee 6,000 asphalt runways.

The field was said to have a single 100' x 200' wood hangars,

to be owned by the U.S. Government, and to be operated by the Marine Corps.

A painting by Gerald Asher of a Marine F7F-2N Tigercat night fighter,

departing from Eagle Mountain Lake, with a Martin PBM Mariner flying boat visible on the seaplane ramp.

The Tigercat was being flown by Captain Don Welsh,

as his unit prepared for overseas deployment when the war ended.

Eagle Mountain Lake went into caretaker status in 1946,

and the base became an Outlying Field of NAS Dallas.

According to a research paper by Mervyn Roberts, “After the war ended, Marine Air Group 53,

commanded by LTC Robert Keller, conducted night-fighter training for a few months in 1946.

With the end of the war, the Navy was closing bases across the nation.

This was part of a downsizing from a wartime peak of 177 to 80 Naval Air Stations.

For a while it seemed Eagle Mountain Lake Base might avoid this fate.

However, the Navy declared the $6,502,000 former Marine Air Base surplus

and scheduled to deactivate it by September 1, 1946.”

Mervyn continued, “This brought up the question over what to do with the base & facilities when it closed.

The City of Fort Worth & Tarrant County both conducted discussions with the Navy over taking control of the airfield.

The city was worried that if the county took control it would compete with the city-owned Meacham Airport.

This would allow customers to negotiate for air services with 2 government entities, to the detriment of taxpayer owners.

In February, City Manager S. H. Bothwell stated it was unlikely they would acquire it.”

City Manager S. H. Bothwell said, “I can’t see any use we would have for it.”

Mervyn Roberts reported, “However, a transfer to the once-reticent City of Fort Worth was announced in July.

By that time it was seen as a valuable windfall to the municipality & to aviation in the area.

Plans called for transferring the city’s aircraft refueling equipment from Lake Worth

in order to use Eagle Mountain as a cross-county refueling point for land-based aircraft & seaplanes.

During the war, Lake Worth was also frequently filled with transiting seaplanes.

The city hoped that transferring operations to Eagle Mountain Lake Base

would be more lucrative because of the runways, lake ramp & improved facilities.

The city also hoped to use the base hospital for convalescing polio patients.

Officials planned to move 25 of the polio victims to the lakeshore hospital by mid-July.

One drawback to Eagle Mountain Lake, however, was that the runways were not adequate

for the heavy transport planes in the post-World War II airline service.”

Mervyn continued, “The City of Fort Worth began to negotiate a formal lease

with the Navy Department for use of the installation for airport purposes.

A memorandum of agreement to transfer the base was signed in July & was supposed to be followed quickly by a formal lease.

However, negotiations dragged on for months due to Navy foot dragging,

leaving the base in limbo while the city paid the monthly maintenance fees.

The city eventually signed a 5 year renewable lease that gave it the power to sublease at will.

This was seen as important because the city hoped to rent space at the base to pay for upkeep.

The venture was not successful & the City announced their intention of relinquishing this lease shortly thereafter.

The Texas National Guard held the lease from February 27, 1947.”

The base was still depicted as "Eagle Mountain Lake (Aux) (Navy)"

on the March 1947 Dallas Sectional Chart (courtesy of Chris Kennedy).

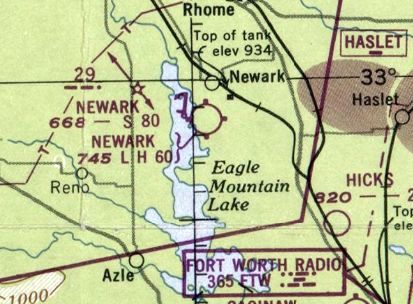

Both the Eagle Mountain Lake airfield & seaplane base were evidently briefly reused as civilian facilities named Newark,

as that is how they were labeled on the September 1948 Dallas Sectional Chart.

Jerry Hightower recalled of Eagle Mountain Lake, “I grew up on the base. We moved to the base in 1948.

The National Guard had the base then. My Dad worked for the State of TX. The State maintained the base.

I was 8 years old when we moved there. I know the base like the back of my hand. I had free run. I could go any where i wanted to.

I know where all the old buildings were & a lot more. I loved the old base. I think it was one of the best times in my life.”

Mervyn Roberts reported, “In December of 1948, the Fort Worth Chamber of Commerce

received a letter from Marine Aircraft Corporation (MAC) in NY

seeking information on airfields with adjacent lakes, for a constructing a factory.

Eagle Mountain Lake Base fit the bill precisely.

Men involved in the Boeing 314 Clipper & JRM-1 Mars flying boat programs had formed the company

and they were reportedly working on a classified tri-phibious aircraft for Arctic regions.

At this point, the Navy still owned the land, with most of it leased to the TX National Guard.

Negotiations progressed rapidly & they soon signed a lease with the Navy.

MAC took over several buildings in July 1949 to do experimental work for the U.S. Navy as well as U.S. Air Force.”

Both the airfield & seaplane base were once again labeled Eagle Mountain Lake on the August 1949 Dallas Sectional Chart.

A 1/4/53 USGS aerial view showed the Eagle Mountain Lake Airfield & its buildings as remaining mostly intact.

Mervyn Roberts reported, “By 1953, Marine Aircraft Corporation began working on crash rescue boats for the Navy.

This project meant MAC required a slice of land belonging to the Tarrant County Water Board

be swapped with land on the base in order to construct a building.”

To make this happen, a county spokesman said the Navy was to “transfer some land which is not needed at one end of the base

to the water district in return for land of equal value at the other end of the base which is needed for the new buildings.”

Mervyn Roberts reported, “This, and other transfers & swaps of land were to complicate the title to the land when it was eventually disposed of.

Marine Aircraft Corporation went bankrupt in 1954 & the hangar reverted to National Guard use.”

According to Ned Gilliand in 1954-55, “Eagle Mountain Lake... was where then-classified sonar dipping was developed”

for the Navy's Bell Model 61 XHSL-1 tandem rotor helicopter.

The helicopters were based at nearby Hicks Field.

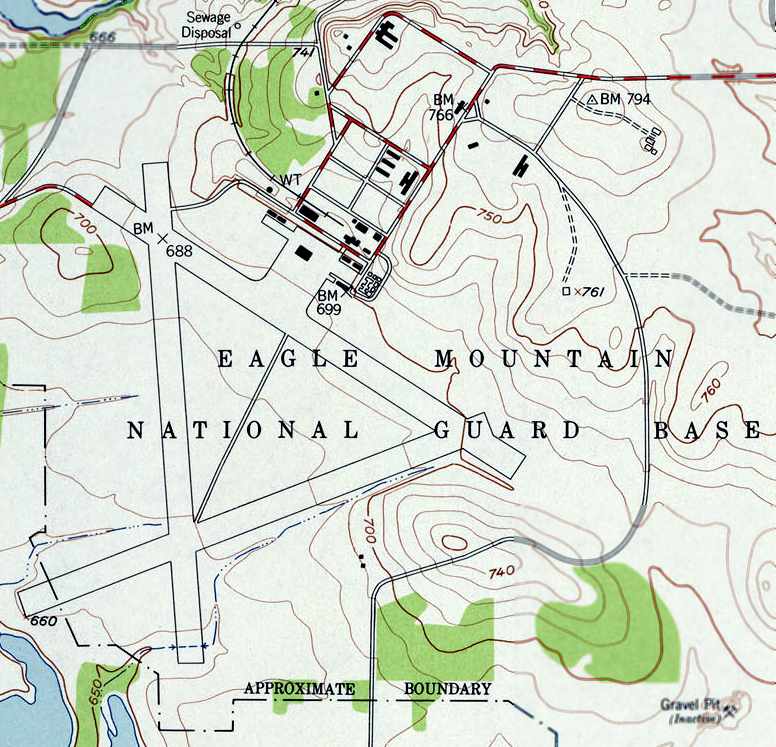

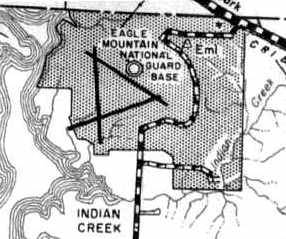

The airfield was labeled “Eagle Mountain National Guard Base” on the 1955 USGS topo map.

A 1956 aerial view showed the airfield remained intact, but unused.

Mervyn Roberts reported, “In 1956, Eagle Mountain Lake was again declared surplus.

The Navy still held the title to the land as a contingency airfield in the event of war.

However, by this time it was no longer thought useful to maintain the base.

So on March 19, 1956 they requested that Congress approve the disposal of the property

as long as it could be maintained as an airfield subject to wartime mobilization requirements.

All federal agencies were given 3 weeks to express interest in the property.

Only 2 federal agencies expressed any interest.

The Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA) responded on April 5, 1956

that it was operating & maintaining an air navigation aid on the base

and requested that provision be contained in the sale or transfer to the effect that the CAA

will be allowed to continue to operate its facility in order to ensure safety of aircraft in the area.”

Mervyn continued, “Major General K.L. Berry from the TX N.G. also responded.

He stated that the State of TX was interested in acquiring the property in its entirety,

as a training center for the 49th Armored Division, TX National Guard.

The TX N.G. utilized only a portion of the land area for armory & training purposes

primarily for the 249th Tank Battalion of the 49th Armored Division.

Sections of various government agencies also used the base for training

including one 6-month period of emergency training of personnel from Carswell Air Force Base,

a short course for the FBI, as well as State Highway Patrol, Fort Worth General Depot, and other organizations.

Major General Berry further noted that the TX N.G. was working with Congressman Jim Wright

and other legislators from TX to submit a bill requesting conveyance of the land by quitclaim deed.

A quitclaim deed is used to convey real property without any warranty as to the full title & other interests in the property.