|

Welcome

to Continental Lodge #287's Home Page. We Fraternally invite you to

view our Communication and visit us on our regular meeting night. We

meet on the first Wednesday of the month at Grand Lodge, 71 West 23rd

Street in the Renaissance Room on the 6th Floor at 7:30PM. Our

Brothers meet for dinner prior to the meetings. Check the

Communication for location and feel free to join us..... Dutch of

course!!

Be Well, God Bless and let our Brotherly Love Spread Around the

World!!!

|

|

|

Sign Our GuestBook

View Our GuestBook |

| If you are not already a member

of our ancient & honorable fraternity, and would like additional

information, please contact this Lodg or any of our fraternity.

Although we cannot directly solicit members, we will be pleased to

respond to your interest by answering your questions and will gladly

provide a petition at your request. |

|

| |

Home Home

|

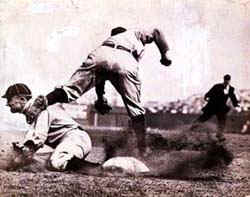

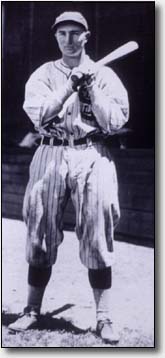

"The Georgia Peach" was one of the fiercest competitors in baseball history,

Ty Cobb went on to be one of t he best of all time. Cobb is the only American League

player to hit over .400 three times. He holds the major league record for lifetime batting

average (.366), most years leading the league in batting (12) and hits (8). He was a

terrific base stealer and has the all-time record of stolen bases of home plate (35).

Often overlooked is that he led the league in RBI four times and had 100 or more seven

times. Cobb also started the practice of swinging multiple bats in the on-deck circle to

make the bat feel lighter at the plate. Cobb was one of the five original members and

leading vote getter elected to the Hall of Fame in 1936. he best of all time. Cobb is the only American League

player to hit over .400 three times. He holds the major league record for lifetime batting

average (.366), most years leading the league in batting (12) and hits (8). He was a

terrific base stealer and has the all-time record of stolen bases of home plate (35).

Often overlooked is that he led the league in RBI four times and had 100 or more seven

times. Cobb also started the practice of swinging multiple bats in the on-deck circle to

make the bat feel lighter at the plate. Cobb was one of the five original members and

leading vote getter elected to the Hall of Fame in 1936.

Return To

Last Page |

Ralph

Metcalfe

Born May 29, 1910, Atlanta, Ga. Died October 10, 1978.

Eddie

Tolan (centre) practicing with Ralph Metcalfe (left) and George Simpson (right) Eddie

Tolan (centre) practicing with Ralph Metcalfe (left) and George Simpson (right)

In the early 1930s, Ralph Metcalfe was the prime U.S. sprinter, winning most of the

national titles. He competed in both the 1932 and 1936 Olympic Games, ending up with one

gold medal, two silvers and a bronze.

At Marquette University, Metcalfe won the national collegiate 100-220 double three

straight years from 1932 to 1934. He did the same thing at the AAU meet during the same

period and wound up with five-straight titles in the 200-220. Overall, counting indoors

competition, Metcalfe won 11 AAU sprint titles, one of the highest totals on record. At

the 1932 Olympics, he was second in the 100 and third in the 200. In 1936, he finally won

a gold medal in the 4 x 100 relay after taking second to Jesse Owens in the 100. He tied

the world 100-meter record of 10.3 eight times and the world 200 record once. He later

became a successful businessman in Chicago and was a member of the U.S. Congress at the

time of his death. Return

To Last Page |

|

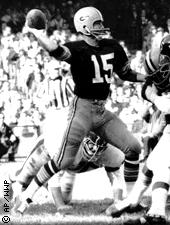

| Bart

Starr

The fact that fans still recognize him isn't what surprises Brian Bartlett

Starr. As quarterback for the Green Bay Packers dynasty that won five NFL

championships in seven years, being recognized is to be expected. What astonishes Starr,

64, is that young people who weren't alive when the Packers won Super Bowls I and II (1966

and '67) know who he is. that won five NFL

championships in seven years, being recognized is to be expected. What astonishes Starr,

64, is that young people who weren't alive when the Packers won Super Bowls I and II (1966

and '67) know who he is.

"It's nice to be recognized," he says. "But some are people who, when

you first glance at them, you think, 'They're too young to know who I am.' That's when

it's really an honor."

Perhaps this pro-football hall of famer is also caught off guard because he is as

modest as they come.

"I was an overachiever," Starr admits. "I was smart and courageous and

had a committed work ethic. But I didn't have the physical talent many of the quarterbacks

had. I had to work harder. I was also blessed to be with a group of talented players and

coached by a phenomenal individual (Vince Lombardi) with a great staff."

A Packer throughout his careers as player (1956 - 71) and coach (1975 - 83), Starr is

still welcomed as a local hero in Wisconsin as well as in his home state, Alabama. The

Montgomery native, who played college ball at the University of Alabama, and his wife live

in Birmingham to be close to the rest of the family. He says he doesn't miss football.

"I'm very happy where I am," says Starr, chairman of National Healthcare

Realty Management. "I love being in a service-oriented business, and I love

Birmingham. Ten years ago, we lost our second son [apparently due to cocaine use]. And our

oldest son, Bart Jr., started leaning on my wife and me to return to Birmingham so we

could be nearer to each other. It may be the best move we ever made."

In nine years the company Starr started has grown into a major player in the medical

field. But his pride in the company's success is matched by the pleasure he gets from

working alongside his son. "As I'm saying this, Bart Jr. is down the hall. That's

something I wouldn't trade for anything." Return To Last Page |

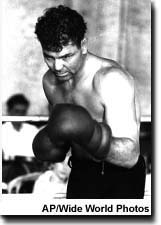

| Jack

Dempsey

William Harrison "Jack" Dempsey was purely and simply, the greatest fistic

box-office attraction of all time. And, not incidentally, one helluva fighter, to boot. If

Dempsey's opponent could walk away from a fight, it was considered a success. S ome 60 of them, including those he met in exhibitions, never walked away from

the first round, so great was his punch. Dempsey was the perfect picture of the ring

warrior. Approaching his opponent with the teeth bared, bobbing and weaving to make his

swarthy head with the perpetual five o'clock shadow harder to hit, his black eyes flashing

and his blue-black hair flying, Dempsey took on the look of an avenging angel of death. ome 60 of them, including those he met in exhibitions, never walked away from

the first round, so great was his punch. Dempsey was the perfect picture of the ring

warrior. Approaching his opponent with the teeth bared, bobbing and weaving to make his

swarthy head with the perpetual five o'clock shadow harder to hit, his black eyes flashing

and his blue-black hair flying, Dempsey took on the look of an avenging angel of death.

His amazing speed and lethal left hook combined with an anything-goes mentality bred of

necessity in the mining camps of his youth, making every bout a war with no survivors. He

used every possible means at his disposal to win, his definition of survival less a

breaking of rules than a testing of their elasticity -- hitting low, after the bell,

behind the head, while a man was on the way down, and even while he was on the way up.

"Hell," he said, "it's a case of protecting yourself at all times."

But Dempsey never had to ___ his opponents did. After having spent several years

out-boxing the local sheriffs, Dempsey came out of the west with a fearful record, a

nickname, "The Manassa Mauler," and a manager named Doc Kearns, who was to play

spear carrier to Dempsey's greatness. With an animal instinct, an inner fury and a lust

for battle a searing path through the heavyweight division. Dispatching contender Fred

Fulton in just 18 seconds in July of 1918, Dempsey proved he was no one-fight phenomenon

as he followed that up with a 14-second knockout of former "White Hope" claimant

Carl Morris. Now all that stood between "The Manassa Mauler" and the heavyweight

crown was a small mountain by the name of Jess Willard. But after one puerile jab with the

left, Dempsey whipped out his meal ticket, left hook, and left a dazed Jess Willard on the

floor, his jaw shattered in seven places, his dreams of retaining his title just as

shattered.

Dempsey would become a legend in his spare time, defending his title but six times in

the next seven years. Still, they were almost all classic feats of arms, fights that made

ring history in the ring and at the box office as well.

But Jack Dempsey's place on the boxing landscape cannot be measured by barebone

statistics alone. He had fewer fights than Jimmy Baddock, fewer knockouts than Max Baer,

and fewer wins than Primo Carnera, three of his successors -- in name only. What Dempsey

had that no one else had was the ability to capture the imagination of the American

sporting public. For he alone spawned "The Golden Age of Sports," becoming the

greatest gate attraction of all time, without exception, catnip for the masses who paid

millions of Coolidge dollars for the privilege of witnessing this legend in action. Return To Last Page |

| Sugar

Ray Robinson

Sugar Ray Robinson, also known as Walker Smith, first put on the

gloves in the same Detroit gym where Joe Louis got his start in the fight scene. Grace, speed and power---knockout power from both hands.

Sugar Ray had everything he needed for a long, successful career as a welterweight and

middleweight champion. From his first pro fight in 1940 at age 20 against Joe Echevarria

to his final bout in 1965 against Joey Archer, Robinson compiled a 175-19-6 record that

included 109 knock outs. He won the world middleweight title on five occasions and was

welterweight champion from 1946-51. the fight scene. Grace, speed and power---knockout power from both hands.

Sugar Ray had everything he needed for a long, successful career as a welterweight and

middleweight champion. From his first pro fight in 1940 at age 20 against Joe Echevarria

to his final bout in 1965 against Joey Archer, Robinson compiled a 175-19-6 record that

included 109 knock outs. He won the world middleweight title on five occasions and was

welterweight champion from 1946-51.

Columnist Jack Newfield, who has written a biography of Sugar Ray Robinson, joins Dick

Schaap in Victory Yard for the Sugar Ray Robinson Night at the Fights edition of Friday

Night at the Fights. Though Newfield was around Robinson a lot during his career and

dubbed him "the perfect fighter," he also points out that Robinson was

"hard to get to know."

Later in his career, Robinson was responsible for changing the economics of boxing by

exploring ancillary rights owed to performing fighters. He also created boxing’s

first "entourage" when he traveled abroad in 1951 as Sugar Ray carefully

maintained his own style throughout his long career. Robinson also had a penchant for

arranging quick rematches after his rare losses in the ring, and vengeance was usually

his. "Ray was always at his best in adversity or when he was under pressure,"

Newfield says.

The first fight of the night is Robinson against Jake LaMotta VI. It is the sixth time

they have gone toe-to-toe—this one is February 14, 1951 for the world middleweight

title at Chicago Stadium. Robinson had won four of their five fights. As Newfield puts it:

there was "bonding in the brutality." This is the fight made famous by the scene

in Martin Scorsese’s film Raging Bull in which LaMotta (played by Robert DeNiro)

displays his famous chin.

The second bout of this night is Robinson against Randy Turpin II from September 12, 1951

in New York. Two months earlier, Robinson has lost his title to Turpin in London after

going into the fight unprepared and tired from extensive partying in Paris.

Next up, Schaap and Newfield look at the dream match-up of Robinson versus Rocky Graziano.

This was the only fight between the two extremely popular fighters. They met on April 16,

1952 at Chicago Stadium. Both were a little past their primes, but Robinson would take

this fight as inspiration to try and step up into the light heavyweight class. He tried

and failed against Joey Maxim in the blistering heat of Yankee Stadium two months after

the Graziano fight.

The final fight of "Sugar Ray Night" is Robinson versus Gene Fullmer IV for the

middleweight belt on March 4, 1961 in Las Vegas. The first three fights between the two

had split—a win each and a draw in their third battle in December of 1960. Newfield

and Schaap discuss whether or not Robinson stayed on the stage too long. Robinson was 41

when he fought Fullmer the fourth time, a full decade after his first title win.

Return To Last Page |

| Matthew

Webb

BESIDES WG Grace, 1998 also marks the 150th anniversary of the other lustrous

sportsman of the Victorian age. Captain Matthew Webb, the first man to swim the English

Channel, was born on January 19, 1848, six months earlier than WG, at Dawley, now part of

Telford. Grace lived until 1915 but had appeared in only the first two home Tests ever

played (at The Oval in 1880 and 1882) by the time Webb perished, at 35, on July 24,

1883, as he attempted to swim the rapids below Niagara Falls.

Webb was the son of a Shropshire doctor. He learned to swim in the Severn at

Coalbrookdale. At 12 he enlisted on the Conway naval training ship on the Mersey, whence

he joined the Rathbone line of cargo ships plying the East Indies and China trade routes.

In 1874, by then a master with the Cunard line, he retired to concentrate as a

professional on the new craze of endurance swimming. For starters he announced he would be

the first to swim the English Channel. The world scoffed.

On August 24, 1875, smeared in porpoise oil for insulation and wearing a crimson

costume of silk made by the firm that would later make Prince Ranjitsinhji's cricket

shirts, Webb dived into the water off Dover's Admiralty Pier. Twenty-one hours and 45

minutes later, having covered 39 sea miles,

he waded ashore at Calais, passengers and crew of the outgoing mailship The Maid of Kent

leaning over the rails to serenade his last few strokes.

Webb logged in his diary: 'Never shall I forget when the men in the mailboat struck up

the tune of Rule Britannia, which they sang, or rather shouted, in a hoarse roar. I felt a

gulping sensation in my throat as the old tune, which I had heard in all parts of the

world, once more struck my ears under circumstances so extra-ordinary. I felt now I should

do it, and I did it.' He slept for 12 hours in the Hotel de Paris, then returned by boat

to Dover saying 'the sensation in my limbs is similar to that after the first day of the

cricket season'. At a welcoming banquet at the Royal Cinque Ports Yacht Club the Mayor of

Dover announced himself 'overwhelmed at an Englishman doing what has never been done

before and will never be done again'.

The Daily Telegraph proclaimed: 'At this moment the Captain is probably the best-known

and most popular man in the world.' Even the New York Times wrote: 'London baths are

crowded, each village pond and running stream contains youthful worshippers at the shrine

of Webb.' The Stock Exchange set up a testimonial fund. It raised an exceptional A2,424,

of which Webb gave A500 to his father and invested A1,872 for a guaranteed annual income

of A87 for life. He toured the world lecturing and swimming. He won A1,000 for an American

'Channel equivalent', crossing from Sandy Hook to Manhattan Beach, and the same sum for

beating the US champion Paul Boyton in a 'world championship race' off Nantasket Beach. He

got another four-figure sum for 'remaining afloat in a tank of water for 128 hours' at the

Boston Horticultural Show. He did no end of that sort of thing.

Webb and his wife Madeleine now had two children. With his fitness giving him concern

he decided to play his last card which would, in spite of his spendthrift generosity, set

up the family for life. The famous circus performer Blondin had lately caught the world's

imagination by walking above the Niagara Falls on a tightrope.

Now the great Webb would swim under and across the Falls in all their boiling ferment,

and not only that but he would aim straight through the fearsomely savage whirlpool, a

quarter of a mile in diameter and rimmed by two awful ledges of jagged rock. With railway

companies laying on special trains Webb reckoned his success would net him at least

A12,000, a fortune.

Madeleine was ignorant of his intentions when he traveled to the Falls with a friend

Robert Watson. On seeing from the bank the venomous whirlpool - a sight so terrifying it

had apparently inspired Edgar Allan Poe to write The Maelstrom - Watson wrote: 'As we

stood face to face I compared the fine handsome sailor I had first met with the

broken-spirited and terribly altered appearance of the man who now courted death in the

whirlpool rapids. His object was not suicide but money and imperishable fame.' At 4pm on

July 24, 1883, spectators crammed on each bank saw Webb dive into the river wearing the

same red costume he had worn to cross the Channel eight summers before. He was instantly

gripped by the force of the current.

Charles Sprawson's classic study of the swimmer as hero, Haunts Of The Black Masseur

(Cape, 1992), describes Webb heading straight for the whirlpool: 'At first he kept on his

way, swimming, then abruptly he threw up his arms and was drawn under. His last words to

the boatman had been, 'If I die, they will do something for my wife.' 'Some days later his

body was found by fishermen four miles below the rapids. It had been delayed by the force

of the whirl-pool. His red silk costume had been torn to shreds, and his skull exposed. He

had probably hit the submarine rocks he feared at the sides of the whirlpool.' He lies

buried in the Oakwood cemetery at the edge of the Falls. In 1908, in what would have been

his 60th year, they built the Webb Memorial at his birthplace in Dawley. Its simple

inscription reads, 'Nothing Great Is Easy'.

Return To Last Page |

| Honus

Wagner

Honus Wagner and Babe Ruth finished in a tie behind Ty Cobb when the first

players were voted into the Hall of Fame in 1936. The fan of today may look at the stats of these men and wonder why Wagner stands alongside

the other two. Yet Bill Deane, in his "Awards and Honors" piece in this volume,

credits Wagner with six "hypothetical" MVP awards during his career?for the

years 1900-1903, 1907, and 1909, years in which no award was given. Only Ruth dominated a

league for so long a time.

The fan of today may look at the stats of these men and wonder why Wagner stands alongside

the other two. Yet Bill Deane, in his "Awards and Honors" piece in this volume,

credits Wagner with six "hypothetical" MVP awards during his career?for the

years 1900-1903, 1907, and 1909, years in which no award was given. Only Ruth dominated a

league for so long a time.

John Peter Wagner became "Johannes" and, later, "Honus" or

"Hans," just as Wagner's nationality, German (a "Deutschman") became

"Dutchman," hence Wagner's nickname, "the Flying Dutchman." Bowlegged,

he "looked like a hoop rolling down the baselines" but reached the majors with

Louisville. When the city was dropped from the league, owner Barney Dreyfuss bought

Pittsburgh and took Wagner with him.

In 1900 Wagner won his first of eight batting titles, an NL record. He was stationed

all over the diamond until Frederick "Bones" Ely, the regular shortstop, begged

off. Wagner made three errors in an inning, then got lucky. With men on first and second,

he gave the signal for a pickoff play and dashed toward second; the pitcher delivered to

the plate instead, resulting in a one-hopper that Wagner turned into a double play. Wagner

called it "the best play I ever made."

The Dutchman led the Pirates to pennants in 1901, 1902, 1903, and 1909, when he

outplayed Ty Cobb, and his batting average didn't fall below .300 until 1914. Wagner led

the league five times in RBI and stolen bases, six times in slugging, and seven times in

doubles. When he retired as a player in 1917, he led the NL in hits, runs, singles,

doubles, and triples.

After coaching at Carnegie Tech and owning a sporting goods store with Pie Traynor,

Wagner fell on hard times. Early in 1933, Fred Lieb wrote a column about Wagner's plight,

and new Pirate owner Bill Benswanger made him a coach. Honus boosted attendance and was

given "Days," even in opposing cities.

In Larry Ritter's The Glory of Their Times, Paul Waner remembered, "He must have

been sixty ... [He'd] get out there every once in a while [and take infield practice] ...

a hush would come over the whole ballpark, and every player on both teams would stand

there, like a bunch of little kids ... I'll never forget it." Return To Last Page |

Arnold

Palmer

Born Pennsylvania, USA, Palmer is one of the greatest golfers of the modern era  and probably closest to the

hearts of the American public than any other. and probably closest to the

hearts of the American public than any other.

Palmer, whose father was a club professional, grew up with golf all around him. As a boy,

he crept onto the golf course at dusk and practiced pitching and putting. Although

successful as an amateur, he decided to seek adventure rather than become a golf

professional. In 1951, he joined the US Coast Guard and served for 3 years. Back in

civilian life, he won the US Amateur in 1954.

Confident of his talent, Palmer turned professional on the back of that victory. He had

the good sense to hire a business manager which enabled him to concentrate on winning

tournaments. His game is characterized by precision putting and powerful drives or as

Palmer puts it, "if you can see it you can hole it".

Palmer was made for television when it arrived in the 1960s. He great personality shone

through and earned him enormous popularity. His fans, known as Arnie's Army, sometimes

numbered in the thousands and were quite boisterous in their appreciation. He flew his own

jet and sometimes 'spooked' the host golf course when arriving for a tournament.

Palmer went on to win the Open twice, the US Open once and the Masters four times. He also

served on 6 Ryder Cup squads and represented his country 6 times in the World Cup. His

achievements earned him a place in the Modern Triumvirate along with Jack Nicklaus and

Gary Player. A testament to his love of competitive golf is that he played on the Seniors

Tour.

Coupled with his many victories on the course, Palmer's endorsements have earned him a

large fortune. He also has an interest in several companies including an interior design

company which is largely managed by his wife. It must also be said that Palmer also

sponsors or has set in place the framework to encourage new talent; Curtis Strange's early

training was funded through a Palmer scholarship.

Palmer is a true hero of golf and is fondly remembered for his great achievements and huge

personality. In many ways he helped to shape the modern game and as such deserves our

appreciation and respect.

Return To Last Page |

Lloyd

Waner

Lloyd Waner was the younger and smaller of the Waner brothers, the

best-hitting sibling combo that ever played the game. Lloyd had an 18-year career; big

brother Paul played in 20 big league seasons. For 13 of those years they played next to each other

in the Pittsburgh Pirate outfield. played next to each other

in the Pittsburgh Pirate outfield.

Together they banged out 5,611 hits?517 more than the three Alou brothers, 753 more

than the three DiMaggios, and 1,394 more than the five Delahantys. The Waners were the

second set of brothers to be inducted into the Hall of Fame, following nineteenth-century

pioneers George and Harry Wright.

Born almost three years apart in Harrah, Oklahoma, the Waner boys were very close

growing up. They spent as much time as they could playing baseball, learning to hit

corncobs with broomsticks. Their father, a former professional ballplayer himself,

encouraged them. Paul once commented, however, "Our sister Alma was the best hitter

in the family."

Paul was Lloyd's first hitting coach, instructing him to hit down on the ball and to go

for line drives rather than power. That was good advice, since neither of them was taller

than 5-foot-9, nor weighed more than 150 pounds. Although Paul produced more extra-base

hits (including four times as many homers) than his brother did during their major league

careers, the two had similar batting styles, keeping the bat at rest on their shoulders

until the pitcher began his delivery.

Lloyd's batting success came in part from his exceptional eye. He holds the major

league record for fewest strikeouts by an outfielder with more than 500 at bats?only

eight, in 1933. In 1941 Lloyd didn't fan for 77 consecutive games. He struck out 20 times

only once after his rookie year, and in 18 seasons whiffed only 173 times. His ratio of

one strikeout per 44.9 at bats is the second best in major league history. Waner also

preferred to put the bat on the ball rather than walk; he never took more than 40 free

passes in a season.

Lloyd Waner was one of baseball's first speedsters. After his arrival scouts began to

pay more attention to foot speed than they had in the past. His quickness made him an

outstanding center fielder as well. He led the National League in putouts four times,

including 1931 when he tracked down 515 flyballs, the tenth-best season ever. His 18

putouts in a 1935 doubleheader are also a record.

Signed to a contract with San Francisco of the Pacific Coast League, the younger Waner

sat on the bench for the 1925 season and watched his brother Paul hit .401. Lloyd was

upset because the team had backed out of its verbal commitment to a $1,500 signing bonus,

and on the advice of a Pirates scout he asked for his release early in the 1926 season.

The Seals obliged, and on brother Paul's recommendation the Pirates put the younger Waner

under contract. He hit .345 for Columbia, South Carolina, and was named the league's Most

Valuable Player.

While Lloyd was tearing up the South Atlantic League, Paul was making his major league

debut, hitting .336 with a league-leading 22 triples in 1926. Lloyd reported to spring

training in 1927 with his brother, hoping to win a reserve outfielder position. The Buc

outfield seemed complete with brother Paul, speedy Kiki Cuyler , and slugging Clyde

Barnhart. But Barnhart showed up grotesquely overweight. All the steam baths in Paso

Robles, California, couldn't get him into reasonable condition, so Lloyd won the starting

job.

Lloyd's first year was one to remember. He set the major league rookie record with 223

hits; 198 of them were singles, which equaled Wee Willie Keeler's mark from the nineteenth

century. Waner hit .355 and led the league in runs scored with 133. Big brother Paul led

the league with a .380 average, 131 RBI, 18 triples, and 237 hits. The two Waners combined

for 460 hits and 247 runs, and on September 4 hit home runs in the same inning.

During one exceptionally productive stretch for the two of them in Brooklyn that

summer, a large person of Italian heritage was heard to holler in quality Brooklynese,

"Every time I look there's that little poyson [person] on third and that big poyson

on first." The Waners were christened "Big Poison" and "Little

Poison" in the newspaper.

In 1927 the Bucs edged out the Cards for the NL flag. A story is told that before the

World Series, Lloyd and Paul watched Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig take batting practice. The

younger said to the older, "Gee, they're pretty big guys, aren't they?" The

dumbfounded Pirates were then swept by the powerful Yanks.

But Lloyd later said that the story wasn't true, denying ever watching the Yankees warm

up. He added, "I don't think Paul ever saw anything on a ballfield that would scare

him." The facts bear him out. The Pirates were not squashed by the Yankees in the

Series. Although the New Yorkers won in four games, two of them were decided by one run,

and the final game was lost on a ninth-inning wild pitch. And the Poisons outhit Ruth and

Gehrig,.367 to .357. Lloyd hit .400; his six hits included a double and a triple.

The two brothers went on a national vaudeville tour following the Series, earning

$2,000 a week. Paul noodled on the saxophone, Lloyd pretended to play violin ("Every

so often we'd hit the same notes as the orchestra," he recalled), and they told

baseball jokes. The fans loved them, and they were offered an additional 10-week tour, but

the brothers realized their futures lay on the baseball field, not on the stage, and quit

to begin training for the next season.

Lloyd had more than 220 hits in each of the next two seasons, and led the league with

20 triples in 1929, marking the third consecutive year that a player named Waner was the

NL triples champ. On June 9, 1929, the Waner brothers hit home runs in the same game. Six

days later Lloyd had six hits in a 14-inning contest. Little Poison missed most of the

1930 season with appendicitis but still hit .362. In 1931 he returned with a .314 average

and league-leading 214 hits.

During the next six years, while the Pirates bounced between second and fifth, Lloyd's

average twice fell below .285. But starting in 1935 he hit .309 or better four years in a

row, including a .313 showing in 1938, the year the Pirates lost the pennant late in the

season on Gabby Hartnett's famous "Homer in the Gloaming." Lloyd had a 22-game

hitting streak that season (his career best was a 23-gamer in 1935), and on September 15

the Waners hit homers in the same inning.

By 1939 Buc management was looking to make room for some up-and-coming outfield talent,

namely Maurice Van Robays and Johnny Rizzo. Waner played in only 92 outfield games that

year and 42 the next. Swapped to the Boston Braves, then to Cincinnati a month later, he

batted .292 for the season. When the Reds released him he caught on with the Phillies, but

when they traded him to Brooklyn after the 1942 season he decided to hang the spikes up.

But these were the war years. At age 37, Lloyd had to find a job in a defense plant or

risk being drafted. Branch Rickey asked him to join the Dodgers in 1944, and he did,

hitting .286 in 15 games. Late in the season he rejoined the Pirates, where his career

ended in 1945.

He retired with 2,459 hits and a career batting average of .316. He then scouted for

the Pirates for the next four years and for Baltimore in 1955. In 1967, 15 years after his

brother Paul was elected, Lloyd Waner was named to the Hall of Fame. He died in 1982.

Return To Last

Page |

| Paul

Waner

Paul "Big Poison" Waner wasn't a big man, at five-eight, 153 pounds, but he

was a big talent. Paul hit over .300 twelve straight years. He

collected 200 hits eight times, tying Willie Keeler's record. twelve straight years. He

collected 200 hits eight times, tying Willie Keeler's record.

Waner won three batting titles in 1927, 1934, and 1936. His .380 in 1927 won him the NL

MVP Award.

Paul learned to hit swinging at corncobs in Oklahoma. He stood deep in the box, feet

together, and aimed at the top of the ball, swinging down as in a golf shot, a theory he

later taught as coach. A line drive hitter, he led in doubles and triples twice each.

He wasn't a home run threat, although he hit 15 in 1929. He recognized that approach as

a losing game in spacious Forbes Field and became adept at lining the ball down either

foul line. The worst that could happen was a foul ball. If the ball hit fair, he had extra

bases. In twenty years, Paul had 3,152 hits, including 603 doubles and 190 triples. His

batting average was .333, and he scored 1,626 runs and drove in 1,309.

In his prime he was a fine defensive outfielder with the arm to play right field at

Forbes. Paul was notorious for his drinking. One year manager Pie Traynor convinced him to

lay off the sauce. When Paul's batting average dropped .240, Traynor took him out and

bought him a drink.

But despite humorous stories about Paul's hungover hitting, the boozing probably kept

him from a couple of batting titles and left him only an ordinary player in his last few

years.

The story is that Paul beat out a grounder off an infielder's glove one day in 1942 for

what could have been his 3,000th hit. However, he signaled the scorer to call it an error,

preferring to wait for a clean blow for the big one. The infielder's comment has not

survived.

Waner was named to the Hall of Fame in 1952. Return To Last Page |

| Jack

Kemp

In January, 1995, Jack Kemp announced that he would not seek the Republican

presidential nomination for 1996. He said that his passion for ideas was not matched by a passion for fundraising. Many commentators said

that his withdrawal was a huge loss for the Party and for the country, but that his

influence would continue as a key spokesman for growth and opportunity, and ownership an

reconciliation in America.

passion for ideas was not matched by a passion for fundraising. Many commentators said

that his withdrawal was a huge loss for the Party and for the country, but that his

influence would continue as a key spokesman for growth and opportunity, and ownership an

reconciliation in America.

In March, 1995, Senator Bob Dole and Speaker Newt Gingrich put Jack Kemp at the center

of the tax and economic debate for the '96 campaign by naming him chairman of the National

Commission on Economic Growth and Tax Reform to study how major restructuring of our tax

code can help unleash the entrepreneurial spirit of Americans, grow the economy without

inflation and create greater opportunity for people to escape poverty.

Mr. Kemp currently serves on the Board of Directors of Empower America, a public policy

and advocacy organization he co-founded in 1993 with William Bennet, Jeane Kirkpatrick and

Vin Weber. Empower America is dedicated to three founding principles: expanding freedom

and democratic capitalism around the world; promoting policies to expand economic growth,

job creation, and entrepreneurship for our nation; and advancing social policies which

empower people, not government bureaucracies.

Prior to founding Empower America, Mr. Kemp served for four years as Secretary of

Housing and Urban Development, and proved to be one of our nation's most innovative

leaders in that role. He was the first and strongest advocate of Enterprise Zones to

encourage entrepreneurship and job creation in impoverished neighborhoods and of expanding

homeownership among the poor through resident management and ownership of public housing.

Mr. Kemp also serves as a Distinguished Fellow at the Heritage Foundation, a Visiting

Fellow at the Hoover Institution, and on the Board of Directors of Habitat for Humanity,

the Opportunities Industrialization Centers, and was most recently elected to the Board of

the Prestigious Howard University. In addition, he has been selected as Deputy Chairman of

the International Democratic Union, a worldwide organization of political leaders of the

"center-right," dedicated to advancing the cause of democracy, freedom, and free

market economics.

Before his appointment to the Cabinet, Mr. Kemp represented the Buffalo area and

Western New York for nine terms in the United States House of representatives from

1971-1989. He served for seven years in the Republican Leadership as Chairman of the House

Republican Leadership Conference.

Jack Kemp came to Congress after 13 years as a professional football quarterback. He

was elected captain of the San Diego Chargers from 1960 to 1962 and of the Buffalo Bills,

a team he helped lead to the American Football League championship in 1964 and 1965 when

he was named the league's most valuable player. He also co-founded the AFL Players

Association and was five times elected president.

Mr. Kemp is married to the former Joanne Main. They have four children-Jeffrey,

Jennifer, Judith, and James-and nine grandchildren, and reside in Bethesda, Maryland.

Return To Last Page |

| Dr. James Naismith

Dr.

James Naismith came up with an idea for a different kind of sport in 1891 called

basketball. Originally it was referred to as netball, but today has become one of the

greatest sports ever. Mr. Naismith was a professor at Springfield College and was

struggling with a concept for a new type of game to condition young students during the

winter months after football had ended and the track and baseball seasons were still

several months away. Gym classes at that time tended to be regimented calisthenics,

gymnastics and drills, and the students were restless for active games they could play

indoors. Dr.

James Naismith came up with an idea for a different kind of sport in 1891 called

basketball. Originally it was referred to as netball, but today has become one of the

greatest sports ever. Mr. Naismith was a professor at Springfield College and was

struggling with a concept for a new type of game to condition young students during the

winter months after football had ended and the track and baseball seasons were still

several months away. Gym classes at that time tended to be regimented calisthenics,

gymnastics and drills, and the students were restless for active games they could play

indoors.

During a temporary teaching assignment of a gym class of 18 bored and restless young

men, Naismith conceived of a way to play within the confines of a gymnasium and without

the natural roughness of outdoor games such as football and rugby. In addition to

borrowing elements from lacrosse, rugby and football, Naismith recalled "duck on the

rock" a childhood game from his native Canada, which gave him the idea of tossing a

ball in an arc toward the goal. To keep the game from becoming too rough, he required that

the player with the ball either dribble it in order to run or take only one stride before

passing to a teammate.

On the last day of his teaching assignment, Naismith selected a soccer ball for his new

game and asked the janitor if he had any wooden boxes to be used as goals. The janitor

offered him two peach baskets he had in the storeroom, which Naismith accepted. After

hammering the goals into place and asking the department secretary to type up his 13 rules

of the game, Naismith organized his class into two groups of nine men each. The janitor

was on hand with his stepladder to retrieve the one ball that was successfully tossed into

the basket during the game that day.

Eventually, one of the students suggested they call the game "Naismith ball."

Naismith laughed and said that such a name would kill the game. The student then suggested

"basketball" to which Naismith agreed.

On that December day in 1891, as the first game of basketball was played in the YMCA

gymnasium in Springfield, Naismith not only discovered the solution to his problem of

keeping student-athletes in condition during the winter months, but also created what has

become one of the most popular team sports in the world today.

Naismith was a true believer in the YMCA ideal of emphasizing both spiritual and

physical development. He also believed that girls as well as boys could benefit from

playing the game of basketball. When a group of grade school teachers asked Naismith

shortly after the invention of the game about its suitability for girls, he encouraged

them to organize a girls team and offered the use of the gym. Indeed, during his courtship

of his future wife, Maude Sherman, he encouraged her to play, and when the first girl's

basketball tournament was held in March of 1892 at the "Y," Maude was among the

players.

On top of inventing the game, he also was admitted to the Springfield Basketball

Hall of Fame, which none the less was also named after him. Basketball has come a long way

since Mr. Naismith, but it wouldn't have been possible without him. Return To Last Page |

| Rogers

Hornsby

Rogers Hornsby was suspicious, short-tempered, and the

greatest right-handed hitter that ever lived.

The Rajah hit .300 or better in fourteen full seasons, won the NL batting title six

straight years (1920-1925), is the only right-handed hitter to bat .400 or better three

times and ended his career with a lifetime average of .358, second only to Ty Cobb. Like

Cobb, he was thorny and idiosyncratic, reserving the right to bet on horses and refusing

to read books or see movies for fear it would hurt his eyesight.

His career didn't begin auspiciously; Hornsby made 58 errors at shortstop in the Texas

League and was unimpressive in 18 games with the Cardinals in 1915. Manager Miller Huggins

told him to put on weight and, 25 pounds heavier, the Rajah hit .313 to lead the Cardinals

in 1916.

By the mid-1920s he was the dominant player in the NL, winning the Triple Crown in both

1922 and 1925, when he became the Cardinals player-manager and was also named MVP for the

first time. For the five-year period 1921-1925 his batting average exceeded .400! In 1926

he slumped to .317 but he gave the Cardinals their first pennant and helped upset the

Yanks in a seven-game Series.

Two months after his great triumph, on December 20, 1926, he was traded to the Giants

for Frankie Frisch and Jimmy Ring. Before the trade could go through, Hornsby had to sell

1,000 shares of St. Louis stock lest a Giants player own stock in the Cardinals; he nearly

tripled his money, finally settling for $120,000.

He was traded again to the Braves and then the Cubs. With Chicago in 1929, he hit .380

with 39 homers and 149 RBI, to win his second MVP award in his last full year as a player.

Hornsby managed the Cubs from the end of 1930 until August 2, 1932, when he was replaced

by Charlie Grimm; the Cubs went on to win the pennant and demonstrated their affection for

Hornsby by cutting him out of the World Series pool.

The Rajah finished up with the Browns and managed in the minor leagues for fifteen

years before coming back to lead the Browns in 1952 and the Reds in 1953. He ended his

career as a Mets scout and coach. Hornsby was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1942.

Return To Last

Page |

| Earle

Combs

Hall of Famer Earle

Combs was an exceptional all-around ballplayer who made key contributions to the mighty

Yankee teams of the 1920s and 1930s. He was born in Pebworth, Kentucky,

in 1899. Hoping to become a teacher, he attended Eastern Kentucky State Normal School in

Richmond, where he played basketball, ran track, and starred on the baseball field,

hitting .591 in his final year. 1920s and 1930s. He was born in Pebworth, Kentucky,

in 1899. Hoping to become a teacher, he attended Eastern Kentucky State Normal School in

Richmond, where he played basketball, ran track, and starred on the baseball field,

hitting .591 in his final year.

During the summer he taught in one-room schools, but he soon

learned that he could make more money and have more fun playing semipro baseball. When he

hit .444 for the Harlan team, the Louisville Colonels of the American Association signed

him.

His first professional game was a total disaster. Installed in

center field, he soon made two errors on groundballs. The Colonels overcame those miscues

to lead by a run in the ninth. With two opposing runners on base, another ball bounced

toward Combs and rolled between his legs. Before he could run it down and send it back to

the infield, both runners, and the batter, had joyfully circled the bases to win the game.

Afterward, he sat in front of his locker, bleakly contemplating

life as a Kentucky schoolteacher. Colonels Manager Joe McCarthy approached the

disconsolate rookie. "Look," he said, "if I didn't think you belonged in

center field on this club, I wouldn't put you there. And I'm going to keep you

there."

Combs soon became an excellent outfielder, outrunning flyballs and

snagging tricky grounders. He finished his first season at Louisville with a .344 batting

average. In 1923 he upped his average to .380, and the Yankees bought his contract for

$50,000 and two players.

When spring came around, however, he refused to report to New

York's training camp. He had been promised a percentage of his purchase price by the

Colonels but had received nothing. "I am not a dumb animal to be browbeaten, cowed,

lashed, coerced, or goaded into anything I do not think is right," he announced. The

Colonels paid him.

Combs had been such an accomplished basestealer in the minor

leagues that Louisville fans called him "the Mail Carrier." When he became the

New York Yankees' leadoff hitter, though, Manager Miller Huggins took him aside and

explained that times had changed. With sluggers such as Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and Bob

Meusel in the lineup, the Yankees needed little help in scoring runs. Stealing bases made

no sense when the next batter was likely to hit one into the seats. "Up here,"

Huggins said, "we'll call you 'the Waiter.'"

As a result, Combs never stole more than 16 bases in a major

league season. Had he played for any other team he might have doubled or tripled that

figure. Nevertheless, his scoring record shows the wisdom of Huggins's strategy. Despite

missing most of three seasons due to injury, the Waiter scored more than 100 runs in 8 of

his 12 seasons for a total of 1,186 runs, an average of 99 a season.

The American League's best leadoff man, Combs collected at least

190 hits five times on his way to a .325 career batting average. While Ruth, Gehrig, and

others hit home runs, the left-handed-batting Combs's specialty was hitting line drives to

all fields, although he collected more than his share of extra-base hits. When one of his

drives sliced between the outfielders, he was a good bet to wind up on third base. He led

the AL in triples three times and finished with a career total of 154, averaging more than

one three-baggier for every 10 games he played.

Combs was also a skillful bunter and was especially good at

drawing walks, the last thing a pitcher wanted before facing Ruth or Gehrig. His career

on-base percentage was .397.

The 6-foot, 185-pound speedster broke in quickly with the Yankees

in 1924, hitting .400 in his first 24 games before fracturing his ankle and missing the

rest of the season. Combs's injury probably cost the Yankees the pennant. After winning

flags in 1921, 1922, and 1923, New York finished second to Washington by two games.

In 1925 Combs, fully recovered, showed that his great start the

previous year had been no fluke. He lashed out 203 hits, batted .342, and scored 117 runs.

But Ruth was out of the lineup for much of the year, and several other players had

disappointing seasons. The Yankees plummeted to seventh place.

In 1926 Ruth returned to form, Gehrig blossomed at first base, and

second baseman Tony Lazzeri added another powerful bat to the lineup. The Yankees clinched

the pennant with a victory in St. Louis.

The next day they clowned their way through a doubleheader with

the hapless Browns. Among other hijinks, Combs performed a burlesque strikeout. Perhaps he

should have played with more dedication; he finished the year with a .299 batting average,

the only time he failed to hit .300 until his final major league season.

The exciting 1926 World Series was highlighted by Pete Alexander's

clutch strikeout of Tony Lazzeri with the bases loaded in the final game. The St. Louis

Cardinals beat the Yankees in seven.

The next year featured the New York club that many experts

consider to be the greatest team of all time, the 1927 Yankees. With the bats of Murderers

Row behind them, the Bronx Bombers cruised to the pennant and demolished the Pirates in

four straight games in the Series. During the regular season Ruth slugged his then-record

60 home runs, and Combs set a club record with 231 hits. In 1986 Don Mattingly topped

Combs's mark with 238.

Gehrig was a favorite of Yankee fans, and Ruth was of course the

most popular figure in baseball. But Combs also rated high with both fans and reporters.

In appreciation of his fine season in 1927, the fans in right field at Yankee Stadium took

up a collection and bought him a gold watch. In 1931 sportswriter Fred Lieb wrote, "I

believe if a vote were taken of the sportswriters on who is the most popular player in New

York, I think the vote would go to Combs."

The Yanks won another pennant and swept another World Series in

1928 but fell short the next three seasons. In 1929 Manager Miller Huggins, whose two

favorites had been Gehrig and Combs, died suddenly. In 1931 Joe McCarthy, Combs's original

manager at Louisville, became the Yankee skipper. The next year New York was back in the

Series, toppling the Chicago Cubs in four games.

Combs never played in another Series. On July 24, 1934, he ran

into the center-field wall at Sportsman's Park in St. Louis while chasing a flyball and

suffered a fractured skull as well as shoulder and knee injuries.

In 1935 he appeared in 89 games as a player-coach before retiring

as a player to coach full time. His first coaching assignment was to teach a young

prospect named Joe DiMaggio the intricacies of playing center field at Yankee Stadium.

Combs coached with the Yankees and several other teams through

1954 and then settled down on his 400-acre farm in Kentucky. He was named to the Hall of

Fame in 1970, six years before his death. "I thought the Hall of Fame was for

superstars," the modest center fielder said, "not just average players like I

was."

Return

To Last Page |

| Branch

Rickey

Branch Rickey was a baseball genius, the greatest front-office man the game has ever

known. He was also a

sanctimonious, hypocritical cheapskate, a man who would play fast and loose with the rules

and go back on his word when it suited him. also a

sanctimonious, hypocritical cheapskate, a man who would play fast and loose with the rules

and go back on his word when it suited him.

That he was a successful general manager for 42 consecutive years, for the Browns,

Cardinals, Dodgers, and Pirates, becomes almost irrelevant when compared to how much he

did to shape the modern baseball landscape.

First, he literally invented the farm system in the early 1920s when he was with the

Cardinals. Before that the minor leagues were composed of independent teams that survived

by developing and then selling players to the majors.

Second, he integrated baseball. Nearly five decades later?after Brown vs. Board of

Education, after the Civil Rights Act, after the Voting Rights Act, and after Cassius Clay

became Muhammad Ali?it's easy to underestimate the impact and significance of his decision

to sign Jackie Robinson. Certainly, it was inevitable that baseball's color line was going

to be broken. But when Rickey hired Robinson, America's armed forces were still

segregated, and African-Americans were still being lynched in parts of the country. What

Rickey did transcended the game and became a significant event in the history of the

United States.

Finally, his plans to form a third major league in 1959 convinced the leaders of Major

League Baseball that they had to expand. That was the beginning of a sports explosion in

this country that continues to this day.

Born in 1881 and raised on an Ohio farm, Rickey coached and played semipro baseball and

football to pay his way through Ohio Wesleyan College. A devout Methodist, Rickey kept a

promise to his mother that he would not play or work on Sundays. He wouldn't even travel

on the Sabbath. Of course, later in his career his teams played on Sundays and he always

called the ballpark to check on the day's receipts.

While at Ohio Wesleyan he also coached the baseball team. He had a black first baseman,

Charles Thomas, who was refused admission to a South Bend hotel on a trip to play Notre

Dame. Rickey finally persuaded hotel management to allow Thomas to share his room. In the

room, according to Rickey, Thomas rubbed his hands together and cried to his 21-year-old

coach, "black skin, black skin. If only I could make it white." Years later,

Rickey tearfully retold the story and said it was the genesis of his crusade to break the

color barrier in the major leagues.

A catcher with a strong arm, Rickey began his professional career in 1903, and after

impressing scouts while playing for Dallas he was purchased by the Reds late in the 1904

season. But Reds Manager Joe Kelley released him when he learned that Rickey wouldn't play

on Sundays.

Rickey went back to Dallas in 1905, was sold to the White Sox, and then was traded to

the Browns. He told the Browns that he'd only play from June 15 to September 15 because he

planned to pursue a law degree from Allegheny College and coach the school's baseball and

football teams. And he wouldn't play on Sundays. The Browns agreed to his stipulations.

However, he played only one game that season, going hitless in three at bats. Then he

headed home to Ohio to tend to his seriously ill parents.

He returned to the Browns in 1906 and had his best season, hitting .284 in 201 at bats.

But he got into a conflict with his manager, Jimmy McAleer, who warned Rickey he would

withhold a portion of his salary if he left before the end of the season. Rickey stayed

after college officials at Allegheny gave him a leave of absence, but he told Browns owner

Bob Hedges that he would never play for McAleer again. Hedges obliged by selling Rickey to

the New York Highlanders.

Rickey hurt his arm during the winter, which ultimately sabotaged his career. Because

of the injury, he didn't report to New York until midseason. On June 28, 1907, in his

first game for Manager Clark Griffith, Rickey's arm was still sore, and the Senators stole

a record 13 bases on him. He hit .182 in 137 at bats, and except for two cameo at bats in

1914 when he was managing the Browns, his playing career was over.

He began taking law classes at Michigan and in 1911 became the school's baseball coach.

After he got his degree and went into practice he also agreed to do some scouting for the

Browns. In 1913 Rickey became a full-time employee of the Browns as an executive

assistant, and soon after that became their general manager. In the final weeks of the

season Hedges gave him the manager's job as well, which Rickey kept through the 1915

season. And yes, he stayed home on Sundays, letting a coach handle the team.

Rickey's background in football led him to experiment with different coaching methods,

some of which he'd tried at Michigan. The Browns' 1914 training camp featured handball

courts to improve hand-eye coordination, batting cages, sliding pits, a running track, and

lectures. Rickey strongly believed that there was a "right way" to play

baseball, and that it could be taught.

He refined this approach with the Dodgers in the 1940s, converting an old military base

in Vero Beach, Florida, into Dodgertown, a state-of-the-art spring training complex for

organization-wide instruction. Rickey introduced the first "Iron Mike" pitching

machines there, and he also had strings set up to outline the strike zone for pitching

workouts.

"Gentlemen, I do not know the game of baseball," Rickey, the grand thespian,

would intone with his mellifluous voice at the start of one of his standard spring

addresses, "but I intend to learn it."

His innovations didn't help the Brownies, but his legal background and Michigan

connection did. George Sisler had signed a professional contract as an underage high

schooler without parental consent, but he had not accepted any money. He then decided to

enroll at Michigan. When the pro contract threatened his eligibility, Rickey advised the

family to move to invalidate the agreement. Rickey was thus able to keep the star of his

team, and the grateful young Sisler signed with Rickey's Browns when he graduated in

1915?after Rickey convinced club owner Bob Hedges to break a gentlemen's agreement that

had earmarked Sisler for the Pirates.

By the time Sisler had become a star for the Browns, Hedges had sold the team to Phil

Ball, and Rickey had moved across town to the bankrupt Cardinals as club president. After

serving as a major in a World War I chemical warfare unit with Ty Cobb, Christy Mathewson,

and Sisler, Rickey returned to the Cardinals as president and, saving a $10,000 salary, as

field manager. After the club finished seventh in 1919 while teetering on the verge of

bankruptcy, Sam Breadon bought 72 percent of the stock. Rickey owned the rest.

Breadon demoted Rickey to vice president but allowed him to continue as field manager.

About that time Rickey developed his farm system plan?out of necessity. The Cardinals

could not afford to compete with other teams to purchase top talent from independent minor

league teams.

His task was monumental. First, he developed a philosophy: he would look for speed and

strong arms. Rickey believed those gifts were essential and that other baseball skills

were teachable. But that was the easy part. When he was done, the Cardinals farm system

included 33 teams. In contrast, each major league franchise today operates only five or

six minor league teams.

Rickey had to devise a method of acquiring teams. He had to establish a system of

tracking and evaluating players in every organization in the majors. He had to hire a

network of scouts and organize tryout camps. He also had to develop an organization-wide

teaching system. It was a task perfectly suited to Rickey's energy and intellect, and one

he was able to carry out even though he was still the field manager.

By 1925 the Cardinals were on the verge of becoming a force in the National League.

(Starting in 1926 they would win five pennants in the next nine years.) Rickey wanted to

stay on as manager. But 38 games into the season Breadon ordered Rogers Hornsby to take

the job, and an angry Rickey sold his stock in the team to Hornsby. Rickey finished his

managerial career with a 597-664 record, and never ended a season higher than third place.

Rickey was well suited to being a full-time executive. Although he never uttered an

oath stronger than "Judas Priest" and did not drink alcohol, he was, for all his

religious pretensions, a skilled manipulator of baseball's rules and people. He also had

the gift to spot talent, and it didn't hurt that he was a shrewd trader. Rickey's motto:

it's better to trade a player a year early instead of a year late.

He was also a cartoonist's dream, a living caricature with bushy eyebrows and

big jowls. He wore wire-rimmed glasses, favored bow ties, and smoked enormous cigars. Then

there was his rhetoric. He loved using $5 words, and could he ever turn a phrase.

"Luck is the residue of design," his best known saying, remains in vogue decades

later. He acquired his nickname, "the Mahatma," in the 1940s, when Gandhi became

a player on the world stage. The nickname was somewhat tongue-in-cheek, but it also shows

the respect given to the man who had such a significant impact on the game.

His tenure with the Cardinals proceeded smoothly until 1937, when Commissioner Kenesaw

Landis investigated charges that Rickey was illegally signing and stashing players in his

huge farm system. Landis ordered the release of 73 Cardinal farmhands from Rickey's

"chain gang," and gave the players the right to sign with any team they wanted.

Rickey's parsimony became legendary. Johnny Mize actually believed that Rickey

preferred to have his teams finish a close second so that he could cash in on a

pennant-race gate without having to fork over pennant-winning raises to his players.

Enos Slaughter once said that Rickey "would go to the vault to get change for a

nickel." Eddie Stanky described one negotiation with Rickey, "I got a million

dollars worth of advice and a very small increase." Pittsburgh's Ralph Kiner recalled

Rickey denying his promise for a raise after Kiner had won the NL home run title. Said

Rickey, "We finished last with you and we can finish last without you."

Dodger outfielder George Shuba has a classic Rickey story. He was negotiating with

Rickey and wanted an increase to $23,000. During the meeting, Rickey was summoned to

another office for a phone call. As he waited, Shuba noticed a contract with Jackie

Robinson's name on it for $21,000. When Rickey returned, Shuba agreed to take $20,000.

Later, he found out that the Robinson contract was a phony and that Rickey's phone call

was a setup.

While he was nickel-and-diming his players, Rickey was becoming a rich man. He had a

deal with the Cardinals and Dodgers that gave him a 10-percent commission on every player

sale?talk about possible conflicts of interest. Bill Veeck told a more sinister Rickey

story in the book, Veeck As in Wreck. It seems Rickey once agreed to a deal over the

phone, then went back on his word, and denied that the phone conversation had ever taken

place.

By 1942 Rickey's contract was up in St. Louis. He was fed up with Breadon, and vice

versa. No one really knows if he was fired or if he quit, but he moved over to the Dodgers

without missing a beat. Rickey protege Larry MacPhail was leaving the Dodgers club after

building it into a contender, so Brooklyn hired Rickey as president and general manager.

He also bought 25 percent of the team.

When Commissioner Landis died in 1944, Rickey could move ahead with his plans to

integrate baseball. Landis, a little-known villain in baseball's sordid history of

discrimination, had quashed Bill Veeck 's bid to buy the Philadelphia Phillies during

World War II and stock the team with stars from the Negro Leagues. But by the end of the

war Rickey sensed the timing was right.

He also knew it was a smart move. More and more teams were starting to copy his farm

system, and he wanted, as always, to stay a step ahead of the competition. And unlike

Veeck, who integrated the American League when he signed Larry Doby in 1947, Rickey never

paid a Negro League team for a player, knowing the owners would not want to be blamed for

delaying the end of the color barrier.

Rickey's expansion machinations began in the spring of 1945, when he announced the

formation of the Brooklyn Brown Dodgers to play in a new United States Baseball League

(USBL) and dispatched scouts to search the Negro Leagues for talent. However, the Brown

Dodgers and USBL were a scam designed to hide Rickey's real purpose?the integration of the

established major leagues. At first he intended to sign several black prospects, then he

decided to sign only one. His scouts suggested pitcher Don Newcombe, but Rickey deemed the

19-year-old too young for the pioneer role, foreseeing the abuse the first

African-American major leaguer would encounter.

The second choice was Kansas City Monarchs shortstop Jackie Robinson, who was 26, a

former Army officer, and a four-sport star at UCLA. In their now-famous first meeting,

Rickey warned Robinson of the trials he'd have to endure without being able to retaliate.

An angry Robinson asked, "Do you want a player afraid to fight back?" Rickey

replied, "I want a player with the guts not to fight back."

On October 23, 1945, with the approval of his Dodgers partners, Rickey signed Robinson.

After a brilliant 1946 season in Montreal, Robinson joined the Dodgers in 1947 and was an

immediate star. Rickey's Dodgers thus got the jump on the rest of baseball, signing such

black stars as Newcombe, catcher Roy Campanella, pitcher Joe Black, and second baseman Jim

"Junior" Gilliam. As a result, between 1947 and 1956 the Dodgers won seven

pennants in 10 years.

Rickey, however, did not last long enough in Brooklyn to enjoy all the fruits of his

labors. Walter O'Malley, one of Rickey's partners, wanted control of the team, and his

first order of business was to engineer Rickey's ouster. Here, finally, was someone as

intelligent and devious as Rickey.

O'Malley made his move after the 1950 season, when he led a boardroom coup that forced

Rickey out. Rickey, however, cried all the way to the bank because a clause in his

contract forced the Dodgers to match the highest bid for his stock if he was not rehired.

Rickey produced a $1.25-million offer, more than double O'Malley's estimate of the stock's

value. O'Malley went to his grave believing the offer was a phony, and there's a good

chance he was right.

Rickey moved on to Pittsburgh, laying the foundation for the 1960 Pirates team that won

the World Series. His greatest coup with the Pirates was drafting Roberto Clemente from

the Dodgers, who were trying to hide him in the minors by not playing him regularly.

Rickey's last venture was the Continental League, his response to the majors' repeated

refusal to expand beyond 16 teams. One of his fellow "owners" was Joan Payson,

who eventually acquired the expansion Mets franchise. Rickey was 77 by then, but his

involvement in the proposed new league, which presaged the American Football League, the

American Basketball Association, and the World Hockey League, was enough to put the fear

of God into the major leagues. By 1961 Organized Baseball initiated an expansion program

that has added 12 new teams during the past 32 years.

Rickey died in 1965, less than two weeks before his 84th birthday. He was inducted into

the Hall of Fame in 1967.

Return To Last

Page |

Return To Home Page

|