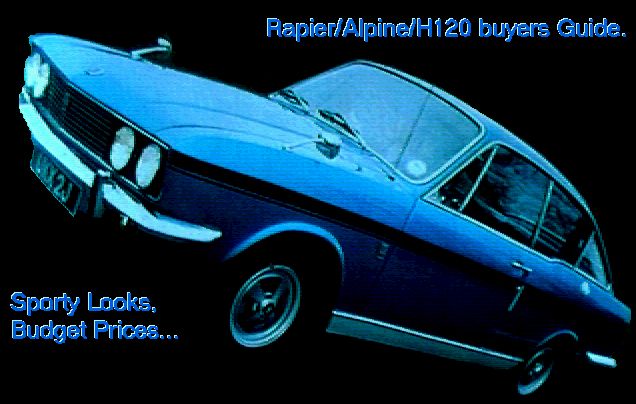

From Practical Classics (January 1995) by Kim Henson.

Once underated and overlooked, the Fastback Sunbeam Rapier and Alpine are attracting more attention from enthusiasts, yet prices are still reasonable. Kim Henson investigates these stylish Hillman Hunter based grand tourers.

So, you want a sporty classic, which is fun to drive and easy to work on, but won`t cost a fortune to buy and run. Tough criteria, but the fastback Sunbeam Rapier and Alpine models of the late 1960s and 1970s are up to it. Arguably better looking than Ford Capris, the Sunbeams are certainly rarer. They are mechanically straightforward, even the Holbay-tuned Rapier H120 version, and can provide fast, enjoyable and reliable motoring in the 1990s. With mechanical spares still relatively easy to find, keeping a Rapier or Alpine on the road is easy.

The attractive interiors are comfortable, with room for up to five adults, and have a lighter and airier feel for back seat passengers than the Capri. Instrumentation in the more basic Alpine is adequate, while in the sporting Rapier and H120 it is very comprehensive. The Rapier has a rev counter plus coolant and oil pressure gauges, while the H120 has an additional oil temparature gauge.

Even in the slowest of the Range, the Alpine, performance is reasonable - reaching 60mph from rest in around 15 seconds, and the car is capable of well over 90mph. It can also cruise happily at 70mph. The 100mph plus Rapier will scoot to 60mph in a little over 12 seconds. And it is more relaxing to drive for long distances, due to its standard fit overdrive. Long motorway trips are eagerly and easily undertaken, the engine just loping along at 70mph in overdrive top.

My Standard Rapier

Commendable Speed

Despite higher gearing, the H120 reaches 60mph in 11 seconds, and the car can exceed 105mph. These figures were commendable in 1968 and are still respectable today. The cars are easy to drive, helped by a slick-changing gearbox, and ride comfort is good. Roadholding and handling are competent, and rated by H120 owners as exellent, although its suspension is firmer than on less powerful versions. Luggage capacity is reasonably good, and the boot is loaded easily from bumper height.

On a personal note, my brother and then my father owned a Rapier in superb condition, back in the late 1970s and early 1980s. I thought it was a wonderful car and always took the oppertunity of driving it whenever possible. On these rare occasions, I enjoyed every minute behind the wheel. It was an imposing, very capable and enjoyably fast car. I only wish I`d bought it when I had the chance in 1981.

Which Model?

Rootes launched the new Rapier in October 1967. Its distinctive fastback looked totally different from, and was larger than, the well-liked Rapiers that had gone before. Indeed, its pillarless coupe bodywork used the floorpan from the then new Hunter range from Rootes. Other common panels are the rear valance and the inner and outer sill assemblies.

As benefitting a car with sporting pretensions, the Rapier used Rootes' twin carburettor 1725cc engine, with an aluminium cylinder head and high lift camshaft from the upmarket Humber Sceptre. The Rapier was instantly recognisable by its four headlamps. Closer inspection revealed reclining front seats, comprehensive instrumentation, standard Laycock de Normanville overdrive, and fully retractable side windows, giving a frame-free outlook to the sides for all occupants. For those seeking two-pedal motoring, Borg Warner automatic transmission was available.

The Rapier was no slouch, indeed by the standards of 1968 it was a fast car. However, in October of that year, the tuned H120 version arrived, with the engine breathed on by Holbay Racing Engines. The resulting machine was considerably more rapid, courtesy of improved engine breathing and twin Weber 40DCOE carburettors on a special inlet manifold, replacing the Strombergs of the normal model. The Holbay used higher gearing than the standard Rapier, allowing more relaxing cruising at high speed. The H120 became more attractive still by the fitting of the then trendy Rostyle wheels, shod with wider tyres, and sported broad body stripes and a bootlid-mounted rear spoiler.

John Bryant owns five Rapiers, including this brown model.

For customers looking for a less expensive car, yet still retaining the character of the Rapier, Rootes applied an earlier model name to a de-trimmed version, the Alpine, in October 1969. By contrast with the car from which it was developed, the Alpine had only a single carburettor - yet still developed a useful 74bhp - and had conventional steel wheels with chromed hub caps, plus far simpler interior trim and instrumentation. Options included overdrive or automatic transmission. For motorists on a limited budget, the Alpine was significantly cheaper than the Rapier. In 1970 you would pay £1503 for an H120, and even the standard Rapier would cost £1282, whereas an Alpine could be yours for just £1141.

Changes.

Engine revisions introduced in March 1972 included new camshafts in the Alpine and Rapier, plus revised carburation for the latter. New seats were specified, along with a three spoke steering wheel. Radial tyres and revised wheel trims were now fitted on the Alpine.

Further changes came about in November 1973, when both the Alpine and the Rapier gained heated rear screens, and the Rapier featured overriders, push button radio, improved exhaust system, and leather trimmed steering wheel. Buyers of the H120 gained new sports road wheels. The following October, tinted glass and electric screen washers became standard fittings. By the end of 1975, the end of the production road was in sight, and although, in January 1976, the Rapier gained the same sports wheels as the H120, this was to be the last major modification. In the same month, the Alpine ceased production and during April the Rapier name became history.

Conventional wisdom was applied to the Rootes 1725cc engines used in the Fastbacks. All were variations on a well proven, pushrod-operated overhead valve theme. Even the overtly sporting Holbay motors are essentially straightforward units with few vices. Given proper maintenance - in particular regular oil and filter changes - the engines usually last 100,000 miles or more before falling oil pressure and rising consumption dictate a major overhaul. On the down side, if one had been run long without antifreeze containing corrosion inhibitors, the waterways within the aluminium cylinder head will have suffered. Heads in good condition are now quite scarce. In any event, if the car you are looking at has anything approching 90,000 miles on the clock, with its original cylinder head, this is good going.

Apart from worn synchromesh on high mileage cars, and final drive units that can whine with increasing volume as the total distance covered clocks up, there are few inherent vices with the transmission. Watch for imprecise gear selection, indicating wear; in good condition the gearchange on a manual version is particularly slick.

There are no particular problems with the simple steering, suspension and braking systems. However, worn front shock absorbers cause dreadful handling and ride characteristics. To rectify this, the front struts need removing and dismantling.

When all windows are wound down, the Rapier becomes a true pillarless coupe.

Spares

Unused, original body panels - especially front wings - are scarce now. However, inner and outer sills and the rear valance, along with the floorpan, are as on the Arrow range saloons, and can still be found. Unused, or even good secondhand chrome and interior trim are scarce.

The good news is that most mechanical items can still be sourced, and the suppliers specialising in Rootes spares seem helpful and enthusiastic.

In all versions, access to the engine and its ancillaries is exemplary. There is plenty of room around the unit in which to wield tools and the traditional overhead valve engines are all straightforward to work on. This also applies to the high performance H120 models, which are no more difficult to maintain than a standard Rapier.

Cylinder head overhauls are the same as any pushrod engine, the main complication likely to arise being aluminium cylinder head corrsion. Bear this in mind before you start work and, if at all possible, arrange to have a spare in stock just in case.

Gearbox removal, for clutch or transmission work, is not a major problem, nor is an engine overhaul. Again, the uncomplicated design - with no need for special tools - pays dividends. It is worth noting that sump removal is possible with the engine still fitted in the vehicle. In addition, the main and big end bearings can be changed without removing the crankshaft, as long as the crank itself is in good condition.

Ovehaul or replacement of the running gear is also relatively easy, although spring compressors - and caution - are needed when dealing with the MacPherson struts.

Bodywork restoration is usually straightforward, but care is needed when fitting the welded-on and very large front wings to ensure correct alignment, and the same goes for the sills. However, these aspects are no more difficult than on most cars.

What you`ll pay.

Even top flight H120s generally sell for £2200 or less, with standard Rapiers in similar condition costing under £1850, and Alpines, about £1650. Average condition cars currently change hands for around £800 (Alpine), £1000 (for the Rapier) and £1300 (H120), while restorable examples are available from around £250 (Alpine), £350 (Rapier) and £450 (H120). At these figures, the fastback Sunbeams represent remarkable value for money, and the H120 in particular provides you with a lot of motor for your cash.

The many virtues of these Sunbeams are nowadays being appreciated. For a relatively modest investment, you can acquire an interesting, practical and competant classic that will be easy to look after, reliable and refreshingly different.

Rust Finder

Rusty examples can be expensive to restore - to the extent that they may cost more to rebuild than it would take to buy a good one. So take care when buying to ensure that the shell is as sound as possible. In addition to the specific areas shown, open the boot and examine the floor and rear inner wings.

FLOOR PAN

Examine the floor from above and below, looking especially closely around its perimeter. Water and salt thrown up by the front wheels can cause serious rot in the front footwells.

OUTRIGGERS

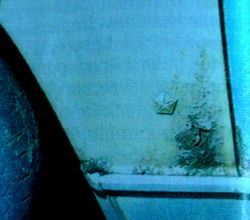

Carefully check the outriggers, found just behind each front wheel, from under the car. Damage like this is quite usual but repairs are not difficult with a DIY welder.

MACPHERSON STRUT UPPER MOUNTINGS

The structure around the upper suspension mounts needs very close scrutiny. Check adjacent inner wings too, from under the bonnet and under the wing.

REAR SPRING MOUNTS

Deficiencies in this area can obviously be potentially dangerous - examine the steelwork very closely. Any repairs here should be carefully seam-welded all round.

FRONT VALANCE

Taking a constant pounding from road debris, the exposed front valance panel is often rusty. Make a point of looking at it very closely, especially at each end of the panel.

REAR VALANCE

Identical to the rear valance on all the Rootes/Chrysler Arrow range saloons, the ones on the Rapier and Alpine are equally rust-prone. Check it very carefully.

FRONT WINGS - UPPER, FORWARD CORNERS

Usually rusty on neglected fastbacks, the tops of the front wings harbour mud and salt if left to their own devices, with the inevitable unsightly results.

FRONT WINGS - TRAILING EDGES

It is not unusual to find evidence here of rust attack. In severe cases there will be large holes (or lots of body filler) to deal with. Check carefully.

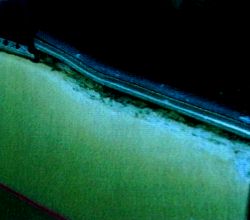

INNER AND OUTER SILLS

Shared with the Arrow cars, the inner and outer sills can rust, but new replacements are readily obtainable. Examine the whole length, inside and out, on each side of the car.

DOORS - REAR LOWER CORNERS

Rust in the panelwork here is common; open each door and examine the corners from both sides. Look for filler and rust on the outer skins as well.

BODY SIDES AND DOOR TOPS

The areas just below the bright trims under the rear side windows are at risk, as are the tops of the doors. Watch for bodging as well as honest rust.

REAR WINGS

The lower edges of the wings, directly in the line of road spray, can disintigrate. Look closely from the outside, and the inside by poking your head under the car.

Check Before you buy

Thanks to Peter Meech, of the Sunbeam Rapier Owners Club, for his help in arranging cars, and to enthusiatic fastback owners John Bryant and Paul Howell.

SROC: Peter Meech, 12 Greenacres, Downton, Salisbury, SP5 3NG (01725 511140).

Email (Glen Mason): 106103.765@compuserve.com

SROC Web Site: http://www.wskisoft.co.uk/SROC/