The Styling story of the Fastback Rapier - ROOTES Owners Supplement.

By Anthony Curtis.

Those concerned: Rox Axe and Ted White. They started work on the Rapier styling in the summer of 1963.

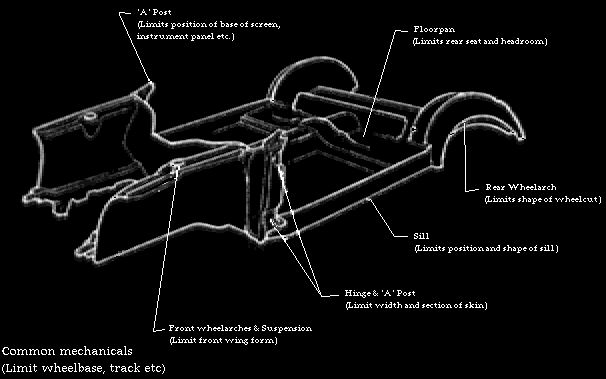

When Rootes Styling Director Ted White and his executive stylist Roy Axe were briefed in mid-1963 to design a replacement for the Sunbeam Rapier, their instructions were detailed and specific. The new car was to restore the sporting image of the Rapier, which had become somewhat run-down since the end of its rallying days; was to have at least as good head and legroom at front; side windows winding down into the body - a Sunbeam feature since the time of the Talbot 90 convertible; and must use the platform/scuttle structure of the Hunter (fig. 1) together with as many of its body pressings as possible - the front wings certainly.

(fig 1) This picture shows the basic Hunter/Rapier platform and the way in which it limited the freedom of design of the stylists.

After some preliminary sketches showing alternative layouts had been prepared and considered a further requirement was added: the new model must be a true fastback. To provide the length necessary both to give such a shape good proportions and to ensure adequate rear-seat headroom it was decided at an early stage to use the Hunter estate car platform which had (and has) an extension at the rear making it 3in longer than its saloon equivalent (a specially made extension is now used). And the horizontal tail-light cluster of the normal saloon would have been difficult to fit into the design and would have led to a ridiculously small boot opening.Typically - typically for stylists, that is - the criteria to be satisfied were as conflicting as they were various, the main challenge being to achieve a fastback shape which left enough depth in the body sides to accomodate the rear window glasses and did not fold the back seat passengers into an attitude of prayer. It is a tribute to Roy Axe's skill that the first working sketch showed a design (fig. 2) which both complied with all the managerial edicts and was clean and elegent; it was a design moreover, which has endured, for it bears a close resemblance to that of the final product. Few people looking at it would realize how limited was the area of freedom: the treatment at the front is fixed by the use of early Hunter type wings, and at the rear by the estate car tail lights.

(fig 2) The first working sketch was clean and elegant - and very near to the finally approved production car.

The main differneces between it and the production Rapier are the use of a completely horizontal line for the body sides, of a one-piece curved backlight and a V-shaped bonnet grille to give extra length. This last feature was also intended to harmonize with a below bumper front pod for an optional air-conditioning kit - another specification must. Later, the air-conditioning reqirement was dropped, but the pod remains.Initial reactions to the first sketch were generally highly favourable, but there were some criticisms of detail and some practical difficulties. One objection was to the thickness of the back pillar, which had been deliberately made full in order to accomodate a vertical runner for the rear side window. Another problem was that the radius of curvature of the backlight glasses was less than 7in. and this, Triplex said, was not on for production cars.

To meet these objections a second sketch was produced (fig. 3) which showed a much thinner rear pillar and a division strip for the large backlight. A quarter-scale clay model was then made up from this design. But Roy Axe and his staff were unhappy about the new treatment of the glass which looked messy and involved no less than five separate side-windows. So although they styled one side in accordance with instructions, on the other they left the original, thicker rear pillar - but of course incorporated the new backlight divider strip. With the alternatives thus easily compared, the original thick pillar idea was chosen and thereafter adhered to.

(fig 3) This version has the thinner rear pillar. One snag was a multiplicity of side windows - five.

By this time Chrysler had aquired an interest in Rootes and the chief stylist, Colin Neal, of Chrysler International came over from the States to view the project. He was fully satisfied with the general approach and the progress made, and was quite happy to leave matters in the hands of Ted White and Roy Axe; relations between the two styling departments have remained cordial ever since. Although very general overall approval is needed for any given styling approach, interference is minimal and suggestions - which remain suggestions - are generally only made when asked for. One propsal that Chrysler did make, however, was that the body line be given a "kick up" at the rear. As Roy Axe and his men had thought of this at an early stage - only to have the idea rejected - the suggestion was taken up with enthusiasm and further sketches drawn , from which a full-sized clay model was made. This kick-up in the body line helped to make the car look thinner at the rear; eliminating the sagging appearance given by a purely horizontal line when viewed from certain angles; made the thick backlight pillar shorter and better proportioned, and let more room in the body sides to recess the glass of the rear side windows.From then on the project might have run speedily and run smoothly to a successful conclusion; visibility studies had been favourable, wind-tunnel tests showed the drag factor to be 0.39 - a good value for a car of this kind - and a great number of Hunter parts were being used including the bonnet and the front wings. But here was the snag. Up to this stage the front wings concerned were those of an early prototype version of the Hunter which was being developed at the same time, although at a more advanced stage. They were fuller and more rounded at the front than those of the final version of the Hunter and upon this fullness the success of the shape depended. The great problem was to minimize the depth of the doors and the bonnet which was greater than would have been chosen had the designers been given a free hand, due to the need to use the Hunter scuttle pressing. the shape of the original Hunter wings, and of the doors and rear wings which were designed to match them, was round enough to prevent the car from looking excessively high-waisted: all hull and no superstructure. Some idea of the difficulties involved can be gained by looking at photographs of early versions of the Bond Equipe, which illustrate the difficulty in achieving a successfull fastback shape when forced to use the doors and bonnet of an ordinary saloon.

(fig 4) This full-sized clay model had production Hunter front front wings and a higher drag factor.

Then came the decision to give the Hunter the square-ended look it has today, which meant a complete retailoring of the doors and the rear wings of the embryo Rapier. Again a full-sized clay model was made (fig. 4) but again Roy Axe was gravely dissatisfied. Among his complaints wsa the fact that the drag factor had risen to around 0.44. Since no dies had been made there was still complete freedom for the doors and rear wings, and since a relatively small investment was needed to produce special front wings for the Rapier only, he argued strongly in favour of a design with fuller, more rounded sides . Eventually his view prevailed and he was then able to design the fuller front wings and body sides that we see on the new Rapier today (fig. 5). Even then the permissible extra fullness was only a matter of 7/8 in. or so, due to the limitations imposed by the need to use Hunter front door hinges and mounting points. But it was just enough to restore the balance of the design, and an additional bonus was that the drag factor returned to its earlier value and, suprisingly, there was a significant improvement in yaw stability in cross-winds.

(fig 5) The final production model - the car `Motor` had on test.

All this, of course, is only a small part of the story: we have not mentioned the Battle of the Bonnet Line, the Affair of the Headlamp Surrounds, or the progressive Simplification of the Radiator Grille. Nor have we considered the disappearance of the recessed bootlid, the depression in the rear parcel shelf or how the brightwork of the rear side-window was balanced by a chrome bead along the body and the two linked together by a "Rapier" badge at the base of the backlight pillar. Then there is the facia layout (fig. 8) - inspired by a Chrysler sketch - and the problems on interior design brought about by seats 1 1/2-in. lower than those of the Hunter to provide adequate headroom.There's more to styling than meets the eye.

Anthony Curtis.