The origin of this subject sinks deep into the history of western playing cards: in fact,

the concept of a "wild card" that can beat the high values of the deck was born with the

tarot.

|  |

No Joker (or equivalent card) belonged to the earlier Arabic tradition, nor to

other archaic playing card systems known, such as Chinese Domino cards or Persian/Indian Ganjifa.

But an extra card featuring a traditional demon is found in many Japanese patterns, and even

in a Chinese one; although their function in play is not the same as a joker, their graphic

look is not too different from the western card. |

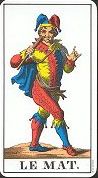

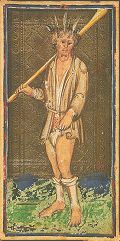

The ancestor of the modern Joker is the classic tarot's Fool.

Despite their close relationship, the latter card shows one main difference: belonging

to a set of 22 trumps, the Fool does not stand as an individual subject.

Nevertheless, in tarot games the Fool takes cards of high rank in the same way

modern Jokers do.

Graphically, the best proof of a relation between the two subjects is provided by the Fool's

direct "descendants" in regional tarot patterns: the Excuse in the French Tarot,

the Sküs in the German Tarock, the Skíz in the

Hungarian Tarokk, etc. are certainly more similar to Jokers than to the rest of the

trumps. |

|  |

Therefore, with very few exceptions, Joker and Fool

cards alone are worth nothing, their paradox power emerging only in the case of a

challenge with another card.

|

The choice of the Fool as a winning subject might appear strange, almost contradictory.

In the past, as well as in recent times, foolishness has never been looked at as

a virtue, and the rags worn by most tarot Fools confirm the low social status of this

personage.

Furthermore, according to the cultural models of the Renaissance, the age during

which the tarot game flourished in most European countries, this choice does not seem to match the

neo-Platonic model of man as the center of the universe, being the only living creature endowed

with thought. |

Renaissance, though, was not a hyper-rational age. Freed from the oppressive

embrace of the mediaeval church, man's progress was no longer guided by the light of pires

on which hereticals were burned, but was finally free to roam, and inspiration also came

from cultures which up to those times had been barely considered, or even proscribed. Among the

latter, for instance, was the Jewish tradition; in particular, the interest of several

Renaissance scholars was caught by its mystical-hesoteric doctrine, the Kabbalah. |

|  |

|

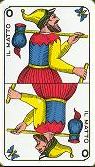

Also the original Italian name of the card, il Matto,

should be discussed: "Fool" is a slightly too liberal interpretation of this expression, for

which a closer translation would probably be "the Lunatic" or "the Madman".

In older times, when freedom of speech was yet to come, lunatics were always entitled

to express themselves freely, to say things that others could not, simply because their

crazy words would not be given credit, although sometimes they were true: their

insanity almost acted as a sort of intellectual shield or privilege. |

|

|

In most archaic cultures, an altered state of consciousness, or even sleep,

was believed to act as a psychic bridge between man and God. In the Bible, for instance,

several personages foresee future events or are given instructions by holy

messengers in their dreams. In the same way, psychic alteration was often

seen as a form of link with evil entities: the numberless cases of "possession" dealt with

by exorcists in the past, today would certainly receive a more rational

assessment. |

Also the ritual state of self-induced trance practised by tribal shamans and bush-doctors is a

typical example of this archetypal concept, once very common in the primitive world.

However, evident traces of this model may still be found in western hesoterism: for instance,

how could a medium makes us believe to be in contact with misterious entities without falling in a

trance? |

|

|

Especially in the past, altered states of mind could have easily been burdened with

social and cultural implications that today would appear absurd.

For instance, in ancient Rome public assemblies were suspended in case one of the

participants was stricken by an epileptic crisis, since this sudden and unknown manifestation

was feared almost as a warning sign from heaven.

Therefore, it is likely that not the Fool's human condition did the unknown author of

the tarot game keep in mind by raising this subject to such a high rank, but his

allegedly privileged metaphysical status, for the same tarot game was probably created as a

symbolic representation of man's progress towards spiritual elevation (see the

Tarot gallery for a discussion of this topic). |

The modern Joker, instead, has an American origin, though once again

descending from Europe, in particular from Alsatia.

Officially, the Joker card was first used in the Unites States, during the second half of the

19th century, for playing the game of Euchre. This game was brought into the

American continent two centuries earlier, by German or Dutch settlers; in fact, the same word

"Euchre" is the English spelling of the old German term Juker, meaning "jack, knave", which later

became the name of the deck's new subject, i.e. the Joker. |

|

|

In this game, the most valuable cards are two Jacks (the one belonging to the trump

suit, and the other one of the same colour), known in play respectively as Right Bower

and Left Bower, a corruption of the German Bauer, "peasant" or "chess pawn",

a name also used for the knave in older card games. Some versions of Euchre use

a third Bower, called the Best Bower : the Joker was actually born to represent

the latter card, although some players still prefer to use another standard subject of the

deck, such as the 2 of Spades. |

|  |

During the second half of the 19th century this extra card was given its present name

"Joker", and by the 1880s it began to appear in Bridge decks as a standard, sometimes with a

further extra blank card which could replace any of the subjects in the case they were damaged or lost.

Only during the first half of the 20th century the Joker cards became two (usually one red

and one black, to match the Bowers' colour, but sometimes one with colours and one in

black & white). Some decks now have three, or even more. |

And a jester is indeed an ideal personage for the crowded court of

playing cards, which includes four kings, four queens and four knaves

or jacks.

Besides some exterior similarities (both the Fool and the Joker wear patched clothes,

feature funny faces and show informal attitudes), there is something

more important that relates these two subjects.

If mental insanity once granted lunatics freedom of speech, and was even believed to bridge

the gap between common mortals and heaven, in most Renaissance households the jester, often

a hunchback or a dwarf, though being the least member of the court as for social rank, was

also the only subject officially entitled to play with the king (or prince, or duke), to

tease him, to tell him things which others could barely do without the risk of enduring

serious consequences. The same glamorous clothes worn by the jester made him clearly

identifiable among all other members of the court: a personage who, at the same time, was

ridiculous yet outstanding, deformed yet witty. |

|

back to