Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields:

Louisiana: Eastern New Orleans area

© 2002, © 2016 by Paul Freeman. Revised 11/23/16.

This site covers airfields in all 50 states: Click here for the site's main menu.

____________________________________________________

Please consider a financial contribution to support the continued growth & operation of this site.

Wedell-Williams Landing Field / Alvin Callender Municipal / Alvin Callender NOLF (revised 11/23/16) - Micheaud Factory Airfield (revised 10/16/15)

(Original) New Orleans NAS (revised 10/16/15)

____________________________________________________

Micheaud Factory Airfield, New Orleans, LA

30.03, -89.92 (East of Downtown New Orleans, LA)

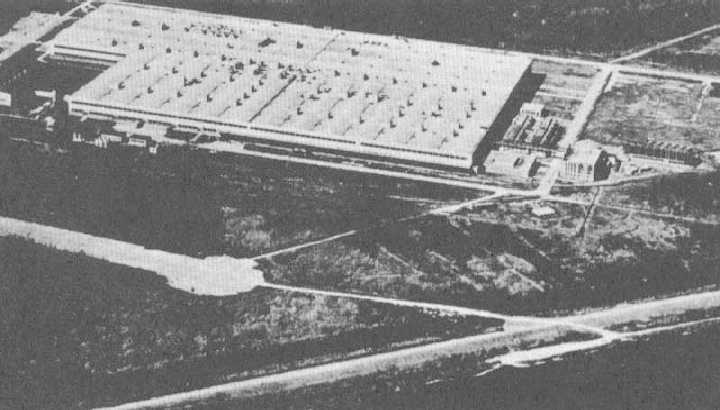

A circa 1940s aerial view looking southwest at the Michoud factory airfield, with the factory in the foreground (courtesy of Carl Hennigan).

In 1942, the New Orleans Higgins Shipbuilding company received a contract to build 200 Liberty Ships -

the largest shipbuilding contract awarded up to that time.

Higgins chose the old Micheaud (Michoud) plantation site on the Intracoastal Canal 10 miles east of downtown New Orleans

for the construction of his revolutionary assembly line shipyard.

Higgins claimed the Michoud Shipyard would turn out 24 ships per month - half of the total national output.

Within 3 short months the entire facility was half completed.

Apparently, the immense amounts of money and human effort poured into the grand project

was of no concern to the Maritime Commission which suddenly & unexpectedly canceled the project

citing a shortage of steel as the reason.

President Roosevelt toured Higgins Industries' City Park Plant in late September, 1942.

After observing Higgins' assembly lines work at full speed turning out motor torpedo boats, antisubmarine boats, and landing craft,

he and Higgins discussed producing wooden cargo planes or "flying boats" at Michoud.

By October 29, Higgins & the War Production Board had concluded preliminary contract negotiations

to build C-76 Curtis Caravans, a molded plywood aircraft partially based

on the metal C-46 Commando cargo plane, for the Army Air Force.

On October 30, the national press reported the imminent award of a 1,200 plane contract.

Shooting for a 6-month initial production date, Higgins requested a halt

to the demolition of a $1,000,000 steel loft at Michoud needed to house Caravan production.

FDR told reporters he had earlier instructed the WPB, the Maritime Commission,

and the Army and Navy to find some defense use for Michoud.

On November 6, 1942, the Army Air Corporation approved a letter of intent for a 1,200 plane contract.

$30 million dollars of the $180 million contract was earmarked for the completion of Michoud's construction & tooling.

But reliance on defense production again proved hazardous.

In August, 1943 the War Department, citing increased aluminum production,

canceled contracts for the more expensive, less efficient, wood-alloy C-76 Curriss Caravan.

Nothing was depicted at the site of the Higgians plant on the 1943 USGS topo map.

The Higgins plant had the USAAF code of “HI” during WW2.

But Higgins still claimed a right to build the metal C-46 Commando.

Higgins proceeded to tool-up for its production along with outer wing panels for the C-46 production at Curtiss-Wright.

In early October his Michoud plant had already begun constructing sub-assembly parts for Curtiss-Wright.

The Michoud Aircraft Plant was officially dedicated on October 24, 1943.

The public gathered in the huge 43 acre main assembly building -

second only in floor-space to Ford's Willow Run plant.

But the War Department soon shifted its emphasis in the air war

requiring more bombers & larger, long-range troop transports.

Higgins' contract for 500 C-46 cargo planes was canceled in August, 1944.

The grand hopes for Michoud & the aircraft industry in New Orleans were dashed.

The net result: only 2 C-46 cargo planes were ever produced by Higgins Aircraft

and the Michoud facility joined the ranks of other "boom or bust" industrial plants.

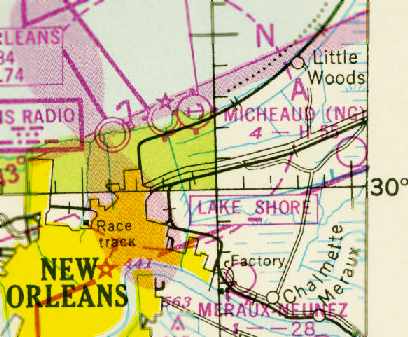

No airfield at the location was depicted on the 1945 New Orleans Sectional Chart (courtesy of John Voss).

The earliest dated depiction of the Michoud Airfield which has been located

was on the 1949 Beaumont Sectional Chart (according to David Brooks).

It described the “Micheaud (NG)” [National Guard] airfield as having a 5,500' hard-surface runway.

During the Korean conflict (circa 1950-53) the Michoud facility was again activated

for the production of 12-cylinder air-cooled engines for Sherman & Patton tanks.

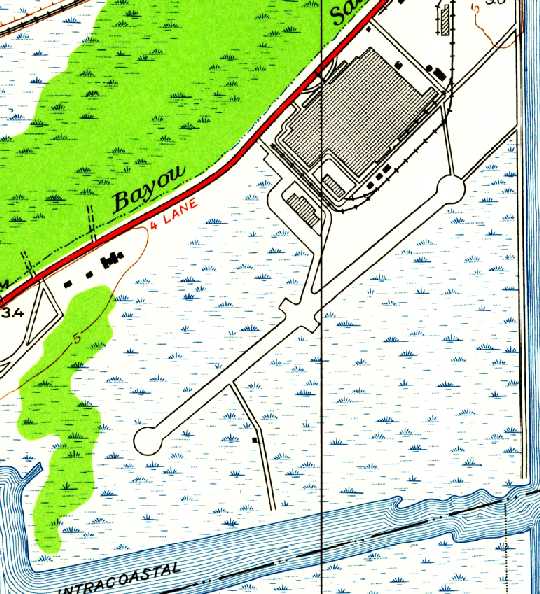

The earliest topo map depiction which has been located of the Michoud factory airfield was on the 1951 USGS topo map.

It depicted a single paved northeast/southwest 5,500' runway with turn-arounds at both ends, and a taxiway leading to the factory.

Neither the airfield nor the factory was labeled.

The earliest dated photo which has been located showing the Michoud factory airfield was a 1952 USGS aerial view.

It depicted the field as consisting of a single paved northeast/southwest runway, with a paved taxiway leading to a ramp adjacent to the factory.

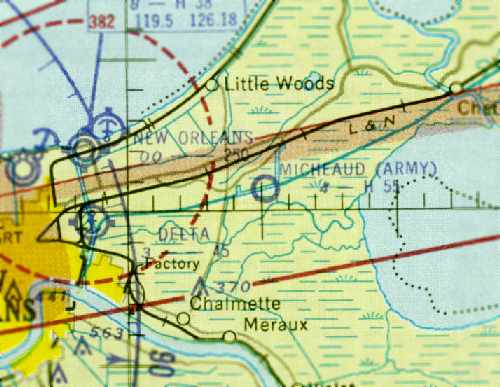

The last aeronautical chart depiction which has been located of the Micheaud airfield

was on the 1952 New Orleans Sectional Chart (courtesy of David Brooks).

The Aerodromes table on the chart described “Micheaud” as an Army airfield having a single 5,500' hard-surface runway.

But the remarks said the field was “Inactive”, with “No facilities”.

The last directory reference which has been located to Micheaud Field

was its listing in the 1953 Aviation Week Airport Directory (courtesy of David Brooks).

It described “Micheaud Field” as “military, inactive – no facilities.”

An undated (circa 1950s?) aerial view looking west showed the northern end of the Michoud runway with the factory behind it.

By the time of the 1956 New Orleans Sectional Chart, the Michoud airfield was no longer depicted at all.

In 1961, with the space race with the Russians heating up,

the National Aeronautics & Space Administration took over the facility for design & assembly of large space vehicles.

The first space project at the Michoud facility was the design & development of the first stage of the powerful Saturn booster,

destined to place man on the moon.

The 1962 USGS topo map continued to depict the airfield in the same fashion as on the 1951 topo map.

The 1965 New Orleans Sectional Chart (courtesy of John Voss)

labeled the site as “Plant & abandoned airport”.

The 1968 USGS topo map labeled the site as “National Aeronautics & Space Administration”,

and showed that a road labeled “Saturn Boulevard” had covered the alignment of the former runway.

A more minor aviation use persisted though, as a Heliport was depicted north of the former runway midpoint.

A 1968 NASA aerial photo looking southeast at the Michoud Assembly Facility,

with the former airfield area right behind the building.

Construction of the Saturn S1B and S1C boosters continued at the Michoud facility until the early 1970s,

when the Apollo program wound down & work began on the Space Shuttle, the next generation launch vehicle.

In a 1976 aerial photo (courtesy of Carl Hennigan),

the former runway had been covered by a road, and was no longer recognizable as a former runway.

According to David Brooks, “I talked to a friend who worked for NASA for 35 years.

He visited the Michoud plant several times & said there was a bit of remains of the runway still there

when the NASA Saturn & latter Shuttle external tank projects were there.

NASA used part of the [former] runway for lay-down storage of large items.”

Eric Rabalais recounted an episode from May 1988: “A Taca Airlines Boeing 737 [Flight 110]

deadsticked it into the grassy area on the south side of the facility, after being struck by lightning.

It was stuck in the mud, but luckily there were no injuries.

The maintenance crew showed up the next day & swapped an engine out.

It later took off from the old runway & headed for Lakefront Airport.

That was an exciting couple of days at work!”

A controller in the New Orleans TRACON recalled the incident:

“The flight was TACA 110. The flight was originally supposed to arrive over the Leeville VORTAC

but due to thunderstorms in the metro area opted to arc south through east.

They basically came into approach airspace from due east.

As they made their descent into the New Orleans area they encountered a rapidly growing thunderstorm.

At this point they were about 10-12 nautical miles northeast of NBG (NAS New Orleans).

They reported the loss of both engines. The weather prohibited them from diverting to NBG.”

The controller continued, “The controller working the aircraft suggested Lakefront Airport.

The 6,600' runway there would be suitably long enough.

We advised Lakefront to suspend any pattern operations & standby for an emergency arrival in the form of an air carrier.

TACA's glide ratio was terrible due to the weather they were flying through.

Options we discussed in the TRACON included a possible emergency landing on the I-10 (1 straight mile for every 5 miles of highway),

ditching in Lake Bourne, or ditching in Lake Ponchartrain.

Given the aircraft's position, deteriorating glide ratio, and uncertainty of landing safely on the highway,

the pilot opted for vectors to Lake Ponchartrain.

The controller issued the heading. The reported cloud ceilings at Lakefront were 1,700' overcast.

The aircraft was northwest-bound when it passed over the Industrial Canal.

At 1,600' we lost the transponder & the aircraft made a hard turn to the left.

To a man we all thought that they had stalled out & spun in. There was no ELT signal.”

The controller continued, “The 2 controllers working were relieved from position by myself & another controller.

The other fellow took the Radar positions working the east side of the approach control airspace;

I took the west airspace & our then non-radar sector.

At that point we had no idea of whether the aircraft made it or not.

Coast Guard helicopters were dispatched from NBG & were en-route to the area.”

The controller continued, “But here's how we found the aircraft.

Lakefront called for an IFR release off Runway 36L. It was a King Air filed IFR for points east.

Normally the release would be runway heading and climbing to 2,000'.

I suggested we issue the departure a right turn to 90 degrees & climb only to 1,500'.

That was our Minimum Vectoring Altitude & it would most likely keep the King Air below the cloud bases.

We solicited the King Air's help, naturally they were more than happy to assist.

They were just west of the Michoud Facility when they reported the B737 intact on the ground at the plant.

To say we were greatly relieved is an understatement.”

A 1988 photo of the TACA 737 (parked on the levee at the left edge of the photo).

It had landed on the levee (the long strip of grass) just to the right of the narrow canal that runs from the top right towards the bottom of the photo).

A controller in the New Orleans TRACON recalled, “The Boeing representatives initially thought about barging the aircraft out

but the field seemed good enough to fly off of once it dried out a bit.

They replaced both engines & about 10 days later flew the aircraft over to MSY for a straight in approach to Runway 28.

TACA had only been operating this particular aircraft (on a lease from Continental Airlines) for about 3 weeks.

It had less than 90 hours total time on the plane. It was for all, intents and purposes, brand new.”

The controller continued, “After more than 2 decades of air traffic control

I still say this is the most splendid piece of air traffic teamwork

and the most incredible piece of flying I've ever been witness to or heard of.

The flight crew had mere seconds to assess the situation as to whether its the lake of the field. They nailed it.”

According to John Artus, “TACA 110 was towed into the Michoud facility for repairs,

and then took off from Saturn Boulvevard (the old Michould Field runway) to the southwest for Moisant Field for further repair work.

So, that flight may constitute the final use of the old Michoud Field runway by an aircraft.”

In the 1998 USGS aerial photo, the huge Michoud Assembly Facility building is just northeast of the center of the photo.

According to Eric Rabalais, “The old runway is the long road that runs from southwest to northeast.”

Note the barges at the inlet at the southwest corner, used to ferry the completed Space Shuttle External Tanks to Florida.

The industrial buildings at Michoud sustained significant damage from Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

A 2005 aerial photo looking north at the Michoud Assembly Facility,

with the former airfield area in the foreground.

A circa 2006 aerial view looking east at a remnant of the former Michoud factory airfield -

the southwestern end of the runway pavement, complete with turnaround pad.

This segment matches the configuration & location of the runway seen in the 1952 aerial photo.

Portions of a taxiway also remain.

As of 2008, Lockheed Martin operates the Michoud Assembly Facility under contract to NASA,

manufacturing the Space Shuttle's External Tank.

Lockheed Martin has been selected to construct the Space Shuttle's successor, the Orion Crew Exploration Vehicle.

According to Lockheed, “Large structures & composites will be built at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility.”

The Michoud Assembly Facilty is located south of the at the intersection of Michoud Boulevard & Old Gentilly Road.

____________________________________________________

Original New Orleans Naval Air Station, New Orleans, LA

30.03 North / 90.07 West (West of New Orleans Lakefront Airport, LA)

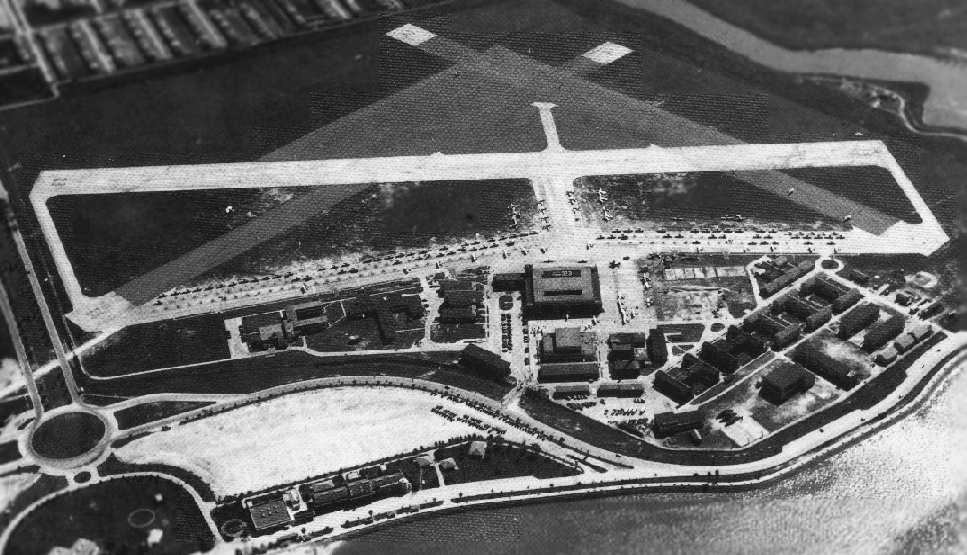

A 1941 photo (courtesy of Carl Hennigan) showing the runways being paved at the original NAS New Orleans.

Nothing was depicted at this site on the 1938 USGS topo map.

New Orleans' original Naval Air Reserve Base was commissioned in 1941,

after the city had donated 182 acres at this site along the shore of Lake Ponrchartrain.

The earliest depiction which has been located of NAS New Orleans

was a 1941 photo (courtesy of Carl Hennigan) showing the runways being paved.

The base initially conducted an Elimination Training Course.

New Orleans soon shifted to a primary flight training mission,

with over 140 aircraft, including N3N "Yellow Perils", Stearmans, and NP Startans.

The earliest aeronautical chart depiction of the field which has been located

was on the January 1943 Beaumont Sectional Chart (courtesy of Chris Kennedy).

It labeled the field as “Naval Air Base” New Orleans.

NRB New Orleans was redesignated a Naval Air Station in 1943.

Its next mission was to conduct instructor training, using a total of over 230 aircraft.

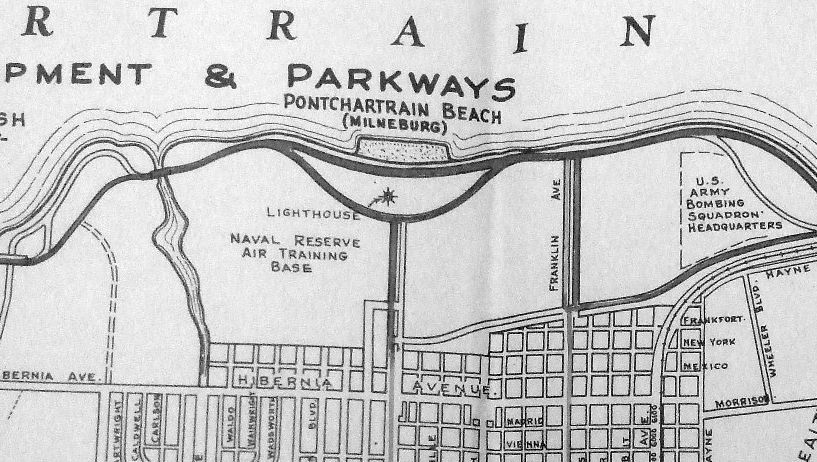

A WW2-era map depicting the “Naval Reserve Air Training Base” (from the National Archives College Park, courtesy of Ron Plante).

Also note the “U.S. Army Bombing Squadron Headquarters” depicted on a small patch of land to the east – apparently a non-flying administrative installation.

The complement of NAS New Orleans in 1944 was a total of 1,431 personnel.

Due to the short runway length, Naval Air Transport Service flights

had to use the nearby New Orleans Municipal Airport (later known as Lakefront Airport) instead.

The June 1944 New Orleans Sectional Chart (courtesy of Chris Kennedy),

depicted NAS New Orleans as having a total of 6 Outlying Fields.

A 3/16/45 aerial view looking south at New Orleans NAS (National Archives photo).

The photo showed one 3,300' concrete runway, 2 shorter asphalt runways, taxiways, a large ramp, a single hangar, and a large number of aircraft.

By the time of the 1945 New Orleans Sectional Chart (courtesy of John Voss),

NAS New Orleans was depicted as having a total of 8 Outlying Fields.

Among these were Moisant Airport (later to become New Orleans International Airport),

A November 1945 aerial view of NAS New Orleans (courtesy of John Anderson)

depicted the field as having a concrete southeast/northwest runway, 2 shorter asphalt runways, taxiways, a large ramp, a single hangar, and a large number of aircraft.

Following WW2, the instructor school transferred to Glenview NAS,

and NAS New Orleans assumed a Naval Air Reserve mission.

A 1948 aerial view looking east (courtesy of Carl Hennigan) showed a large number of aircraft visible on the ramp of the original NAS New Orleans.

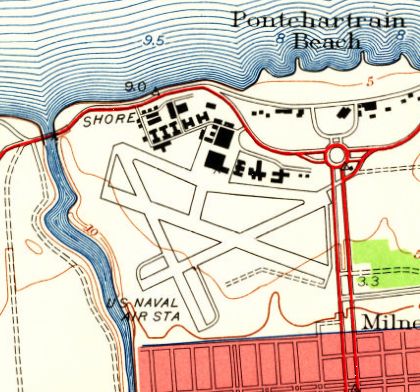

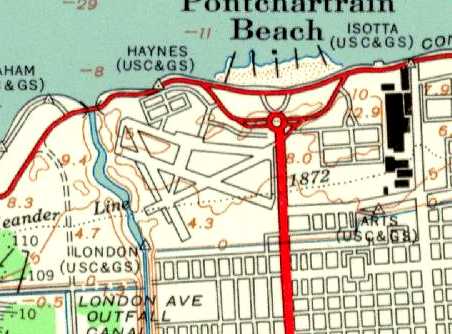

The 1951 USGS topo map depicted the 3 runways, taxiways, and ramps of “US Naval Air Sta” New Orleans.

The last photo which has been located showing aircraft at the original NAS New Orleans was a 1952 USGS aerial view,

with a large number of aircraft visible on the ramp.

The 1953 USGS topo map depicted the 3 runways, taxiways, and ramps of NAS New Orleans,

but the facility was unlabeled.

The September 1956 New Orleans Sectional Chart (courtesy of Chris Kennedy)

depicted NAS New Orleans as having a 3,400' hard surface runway.

As jet aircraft began to appear in the Reserves in the 1950s,

the short runways of New Orleans became a liability.

The Navy built a new & larger facility adjacent to Alvin Callender NOLF, 15 miles southeast.

The new Naval Air Station New Orleans was opened in 1957,

at which point the old field was apparently closed.

The multiple runways & single hangar of the former NAS New Orleans were still visible in a 1960 aerial view (courtesy of Carl Hennigan).

The 1961 USGS topo map still depicted 3 runways, taxiways, and ramps, labeled “U.S. Naval Air Station”.

At some point between 1957-66,

the location of the original Naval Air Station was reused as a Louisiana State University campus.

The 1966 USGS topo map no longer depicted any of the runways,

instead showing roads & newly-constructed buildings,

labeled as “Louisiana State University (New Orleans Branch)”.

Dick Merrill recalled of the original Naval Air Station New Orleans, “I remembered flying over it in the early 1970s

and at that time you still could see a portion of runway.”

In the 1998 USGS aerial photo, no obvious trace remained of the former Naval Air Station.

Dick Merrill recalled in 2003, “Several years ago I drove around the campus of UNO

and found what I think is a building dating back to the NAS days.

It looks like an old power plant building.

If you look at the north end of the campus near the levee,

you will see a line which is the shadow of the brick smoke stack.

The streets and parking lots around the north end look like vintage paving also.

I think I saw a sign that hinted UNO was going to keep the building & make something else out of it.”

The 2002 USGS aerial photo showed that the condition of the site of the former airfield

was not appreciably any different from that depicted in the 1998 photo.

A 2005 photo by Dick Merrill of “the old WWII-vintage brick structure at old Navy New Orleans.

It looks like it survived Hurricane Katrina.

The metal building is also of a similar vintage I think.”

Also note the WW2-vintage brick smokestack.

Bert Sausse reported in 2015 about “the former NAS New Orleans that has since been replaced by the University of New Orleans...

The smokestack did survive Katrina & has been incorporated into an alumni building.

There is a gravel parking lot that is on the north side of campus & just west of the smokestack.

Every now & then, depending upon the amount of traffic the parking lot sees that year, the gravel will part & portions of the airfield resurfaces.

It’s easily identifiable by the aircraft tie-downs that are still in the parking lot below.”

The site of the original NAS New Orleans is located at the intersection of Founders Road & Levee Road.

____________________________________________________

Wedell-Williams Landing Field / Alvin Callender Municipal Airport /

Alvin Callender Naval Outlying Landing Field,

Belle Chasse, LA

29.85, -90 (Southeast of New Orleans, LA)

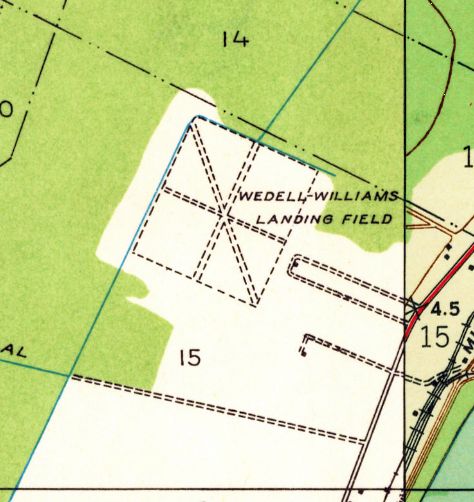

Wedell-Williams Landing Field, as depicted on the 1932 USGS topo map.

An airfield was first cleared on this site in the late 1920s for a nationwide tour by Charles Lindberg.

The earliest directory listing which has been located of this field

was on the 1929 Civil Aeronautics Administration Bulletin #2 (according to David Brooks).

It was listed as a municipal airport.

The earliest depiction which has been located of this airfield was on the 1932 USGS topo map.

It depicted the “Wedell-Williams Landing Field” as being a square outline with 3 unpaved runways.

Note that this was a different airfield than another Wedell-Williams Airport eventually located a few miles to the west.

The field was labeled "New Orleans" Landing Field on the 1934 Navy Aviation Chart V-242 (courtesy of Chris Kennedy).

It was depicted as “Alvin Callender” on the 1935 New Orleans Sectional Chart (courtesy of Roger Connor).

The 1938 Descriptions of Airports & Landing Fields in The United States (according to David Brooks)

described the field as being located 8.75 miles southeast from the center of New Orleans.

It was said to consist of a 2,100' square field, with a 2,100' runway extension on the east side.

It was depicted on the 1939 New Orleans Sectional Chart (according to David Brooks) as a civil airport.

The 1940 USGS topo map depicted “Alvin Callender Field” as a small square outline, without any runway details.

An aerial view looking northeast at the "Alvin Callender" Municipal Airport,

from The Airport Directory Company's 1941 Airport Directory (courtesy of Chris Kennedy).

The field was said to be a T-shape, measuring 2,000' x 2,000', with a 2,000' extension to the east.

A single hangar on the east side of the field was said to have "Airport" painted on the roof.

During WW2, the Navy built a modern airfield (with 3 paved runways)

on the Alvin Callender site as one of 8 satellite fields for New Orleans NAS.

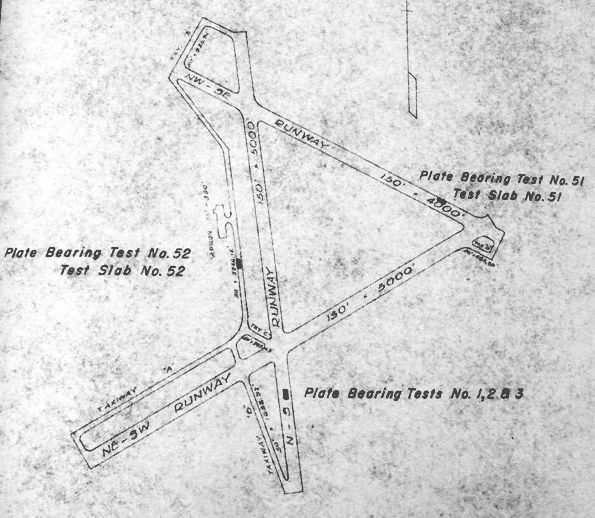

A 1944 Corps of Engineers Report (from the Air Force Historical Agency, courtesy of Ron Plante)

depicted the location of 30” plate bearing tests & concrete slabs on Alvin Callendar Airport.

The airport was shown in its WW2 configuration, with 3 paved runways.

The 1946 Haire Airport Directory (according to David Brooks) described Alvin Callender Municipal Airport

as being owned & operated by the city.

The 1947 USGS topo map continued to depict “Alvin Callender Field” as a small square outline, without any runway details.

The February 1947 Galveston Bay World Aeronautical Chart (according to David Brooks)

depicted Alvin Callender as civil airport.

The 1948 Haire Airport Directory (according to David Brooks) described Alvin Callender Municipal Airport

as being owned & operated by the city.

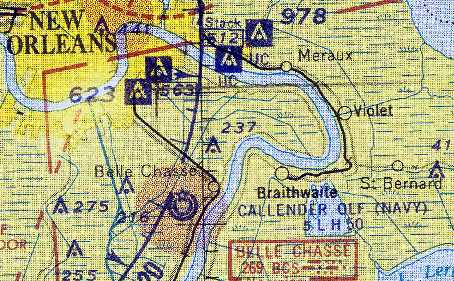

But Callender OLF was depicted as a Navy airfield

on the January 1949 New Orleans Sectional Chart (courtesy of Chris Kennedy)

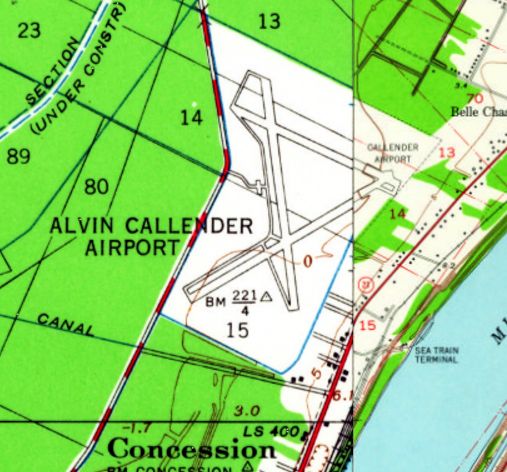

The 1950 USGS topo map depicted “Alvin Callender Airport” as having expanded considerably toward the northeast compared to earlier topo maps,

with 3 paved runways & taxiways.

The 1953 Aviation Week Airport Directory (courtesy of David Brooks) listed the field as “Alvin-Callender Municipal Airport”.

It was described as having 3 paved runways, with the longest being the 5,000' north/south & northeast/southwest strips.

The field was said to offer hangars, repairs, and fuel.

The manager was listed as D.O. Langstaff.

Callender OLF was once again depicted as a Navy airfield

on the August 1954 New Orleans Sectional Chart (courtesy of Chris Kennedy).

The 1954 USGS topo map continued to depict “Alvin Callender Airport as having 3 paved runways.

The last chart depiction which has been located of Callender OLF as an active airfields

was on the September 1956 New Orleans Sectional Chart (courtesy of Chris Kennedy).

The aerodromes table on the chart described Callender as having 3 runways, with the longest being a 5,000' strip.

In 1957, the Navy needed to replace the original New Orleans NAS with a larger jet-capable facility,

and a new airfield with 2 long runways was built adjacent to the southwest side of the old NOLF,

on the opposite side of Olsen Avenue.

This field was dedicated as Alvin Callender Field in 1957,

at which point the original field was presumably closed.

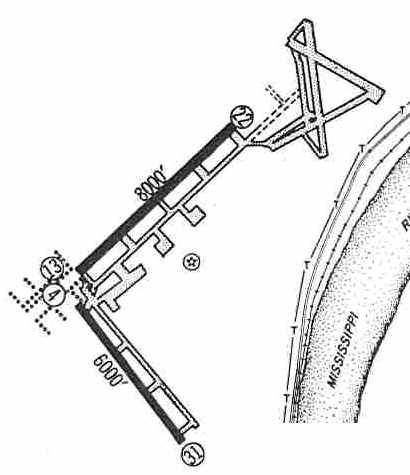

The 1960 Jeppesen Airway Manual (courtesy of Chris Kennedy

depicted the 3 abandoned runways of the Alvin Callender NOLF at the northeast corner,

along with the 2 newly-built runways of the new field.

The runways of the old NOLF have apparently never been reused.

A 2/20/64 USGS aerial photo showed the old NOLF airfield consisted of 3 paved runways (the longest is 5,200'), taxiways,

and the remains of a ramp north of the East/West runway.

There did not appear to be any buildings remaining at the site.

The Harvey VORTAC beacon had been built over the former east/west runway.

The 2002 USGS aerial photo showed that the condition of the abandoned airfield

had not changed very much compared to the 1998 photo.

The field sustained only minor damage from Hurricane Katrina in 2005

(being located at a higher elevation than downtown New Orleans).

It was then was used extensively by rescue helicopters in the aftermath of the flooding.

A circa 2006 aerial photo looking east at the Harvey VORTAC beacon which sits over the former east/west runway.

Bert Sausse reported in 2015, “Alvin Callender Field... the airfield is still attached to the current Naval Air Station via an alternate access road.

The Louisiana Air National Guard, based at NAS-JRB uses this area for additional parking when a major exercise is occurring on base.

Additionally, there are some training & support facilities that are currently lining the runways (as seen on [recent aerial] images).”

____________________________________________________

Since this site was first put on the web in 1999, its popularity has grown tremendously.

That has caused it to often exceed bandwidth limitations

set by the company which I pay to host it on the web.

If the total quantity of material on this site is to continue to grow,

it will require ever-increasing funding to pay its expenses.

Therefore, I request financial contributions from site visitors,

to help defray the increasing costs of the site

and ensure that it continues to be available & to grow.

What would you pay for a good aviation magazine, or a good aviation book?

Please consider a donation of an equivalent amount, at the least.

This site is not supported by commercial advertising –

it is purely supported by donations.

If you enjoy the site, and would like to make a financial contribution,

you

may use a credit card via

![]() ,

using one of 2 methods:

,

using one of 2 methods:

To make a one-time donation of an amount of your choice:

Or you can sign up for a $10 monthly subscription to help support the site on an ongoing basis:

Or if you prefer to contact me directly concerning a contribution (for a mailing address to send a check),

please contact me at: paulandterryfreeman@gmail.com

If you enjoy this web site, please support it with a financial contribution.

please contact me at: paulandterryfreeman@gmail.com

If you enjoy this web site, please support it with a financial contribution.

____________________________________________________

This site covers airfields in all 50 states.