Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields:a

Texas - Northeast Fort Worth Area

© 2002, © 2016 by Paul Freeman. Revised 3/27/16.

This site covers airfields in all 50 states: Click here for the site's main menu.

____________________________________________________

Please consider a financial contribution to support the continued growth & operation of this site.

Arlington Airport / Greater Fort Worth International Airport / Amon Carter Field / Greater Southwest International (revised 3/27/16)

Bell Helicopter Auxiliary Heliport (revised 5/17/08) - Denton Field / College Field (revised 1/27/12) - Hartlee Field (revised 7/11/14)

____________________________________________________

Arlington Municipal Airport / Midway Airport / Greater Fort Worth International Airport /

Amon Carter Field / Greater Southwest International Airport (GSW),

Forth Worth, TX

32.83, -97.05 (South of Dallas Fort Worth International Airport, TX)

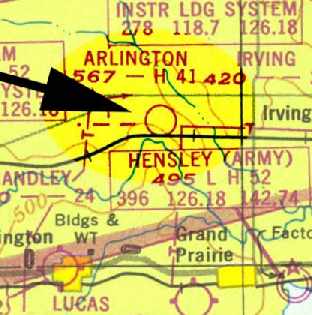

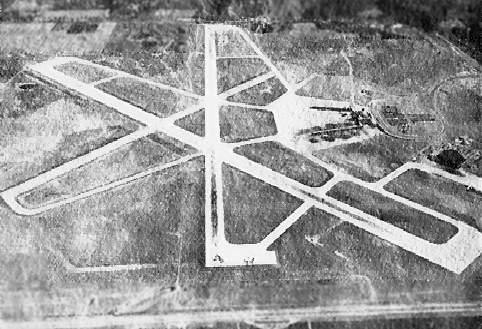

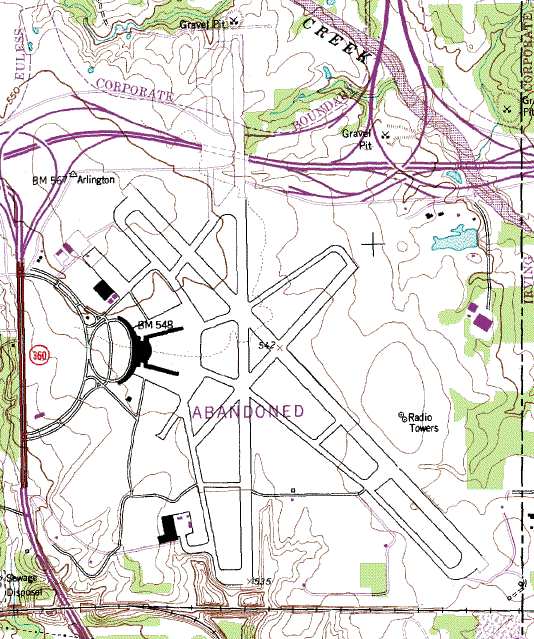

A 10/15/43 aerial view looking north at “Arlington Municipal Airport (Midway Airport)”

from the 1945 AAF Airfield Directory (courtesy of Scott Murdock).

This is a bizarre tale of a massive taxpayer-funded international airport

which was plowed under in a mere 20 years after it opened.

It is perfect example of politics gone wrong,

and incredible levels of wasteful spending.

The vast majority of the millions of airline passengers who pass through

the present-day Dallas Fort Worth International Airport have no idea

of a completely separate airport that once stood on the edge of the current property of DFW.

As early as 1920, officials in Fort Worth were discussing the idea

of a "regional airport" that could serve both their city & Dallas.

At the time, a large swath of sunbaked prairie separated the 2 cities, providing no shortage of suitable land for such a facility.

Dallas, which was in the process of adding paved runways to its own municipal airport, rebuffed the invitation,

and Fort Worth quietly let the idea die.

Just 10 years later in 1930, however, Fort Worth came calling again - and this time Dallas was more willing to listen.

Both cities were feeling the pinch of the Depression,

and the idea of a shared terminal meant less of a financial burden on city coffers.

After some preliminary talks, a site along the Dallas-Tarrant county line was chosen, almost equidistant from each city.

The airport would be within Fort Worth city limits,

but funding & tax revenue would be divided equally between the 2 cities.

By the mid-1930s earthmovers were crawling over the site,

and the cities were in the process of securing a grant from the Works Progress Administration for construction of a terminal building.

This phase of the project came to an abrupt end, however,

when Dallas discovered the terminal would be sited on the west side of the property, a mile closer to Fort Worth.

Dallas withdrew its name from the project in protest, acquired WPA money to build a new terminal at its airport,

and refused to discuss the proposal any further.

With World War II in full swing at that point, any plans to complete the facility were put on hold.

The airport was reportedly called "Midway" at this phase in its timeline,

but it was never labeled as such on any aeronautical charts which have been located.

No airfield was depicted yet at this location on the February 1943 Dallas Sectional Chart.

According to David Brooks, WW2 construction at this field was carried out “under the CAA National Defense Airport Development program.”

The 5/1/43 AAF Station List (according to David Brooks) indicated the field was completed,

and the remarks indicated usage as "ASC" (Air Service Command).

The earliest depiction of the field which has been located

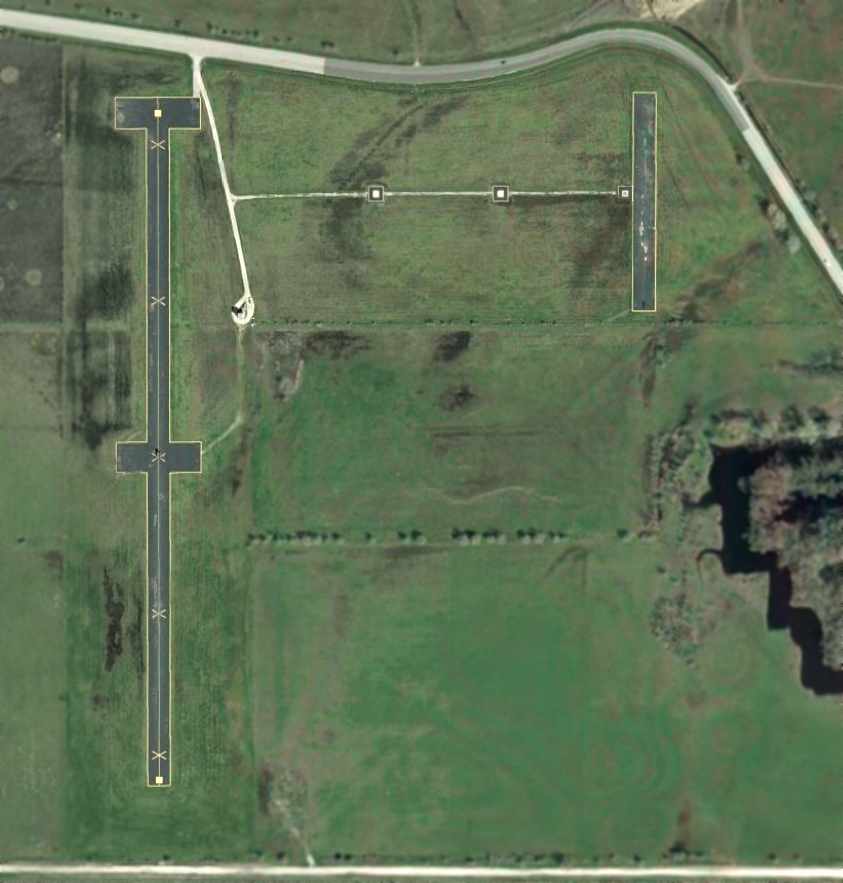

was a 10/15/43 aerial view from the 1945 AAF Airfield Directory (courtesy of Scott Murdock).

It depicted “Arlington Municipal Airport (Midway Airport)” as having 3 paved runways.

The 11/4/43 AAF Station List (according to David Brooks) indicated usage as "ATC" (Air Transport Command).

According to David Brooks, “Another interesting feature is the runway layout with a semi-circular apron for aircraft.

This appears an some other airfields throughout the USA

and several I checked on all fall under the CAAA National Defense Airport Development program.”

The airfield was operated during World War 2 by the military as a training field & for test flights,

improving the airfield just enough to accommodate its aircraft.

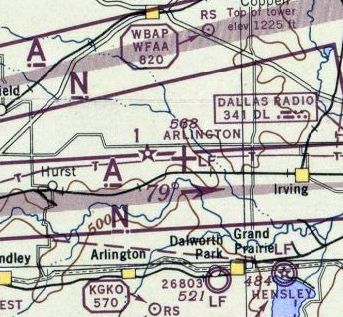

The earliest aeronautical chart depiction of the field which has been located

was on the March 1944 Dallas Sectional Chart.

It depicted an auxiliary airfield at this spot labeled "Arlington",

which must have caused some confusion with the Arlington Navy airfield which also was in operation during that time frame,

several miles to the southwest.

The "Arlington" auxiliary airfield was depicted in the same fashion

on the March 1945 Dallas Sectional Chart (courtesy of David Brooks).

The 1945 AAF Airfield Directory (courtesy of Scott Murdock) described “Arlington Municipal Airport (Midway Airport)”

as a 640 acre square property within which were three 4,100' asphalt runways

(oriented north/south, northeast/southwest, and northwest/southeast),

and a 4,500' east/west sod runway.

The field was said to not have any hangars,

to be owned by the City of Arlington, and to be operated by private interests.

When the war ended Fort Worth was left with a half-built airport -

the facility consisted of a semi-paved runway, a handful of wooden hangars & no passenger facilities.

Meanwhile, Meacham Field was beginning to show signs of strain.

Although it was convenient to central Fort Worth,

development had hemmed it in on 3 sides & opportunities for expansion were limited.

City officials looked east to Midway Airport for a solution -

and once again extended an offer to Dallas to join them in constructing a regional airport on the Midway site.

Dallas refused.

The 1945 Haire Publishing Company Airport Directory (according to Chris Kennedy)

listed “Midway Airport” as being located 6.8 miles North-Northeast of Arlington.

It was described as having 4 asphalt runways.

In 1946 Fort Worth hired a firm to prepare an airport plan for the city,

and the following year it decided to develop "Midway" as its major airport,

Feeling bold - and convinced the Civil Aeronautics Board & Federal Aviation Administration would eventually force Dallas to come aboard -

Fort Worth proceeded with construction at Midway.

Fort Worth officials renamed it Greater Fort Worth International Airport.

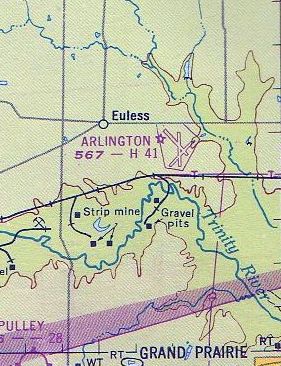

However, the September 1947 Dallas Sectional Chart (courtesy of David Brooks)

depicted the field as "Arlington (Aux)", but with the symbol of a commercial or municipal airport.

The January 1948 DFW Local Aeronautical Chart (courtesy of John Price)

depicted “Arlington” Airport as having 3 paved runways, with the longest being 4,100'.

In 1948 the CAA National Airport Plan recommended that

Greater Fort Worth International Airport be expanded into the major regional airport.

Fort Worth annexed the site & continued to develop the airport with the support of American Airlines,

but Dallas continued its opposition.

The February 1949 Dallas Sectional Chart (courtesy of David Brooks)

depicted the field as "Arlington", and described it as having a 4,100' hard surface runway.

According to the Dallas Morning News,

at one time the feud became so bitter that Fort Worth Mayor Amon Carter refused to eat in Dallas restaurants,

and when business made it necessary for him to be in Dallas, he carried a sack lunch.

In 1950 the Fort Worth City Council renamed the airport Amon Carter Field.

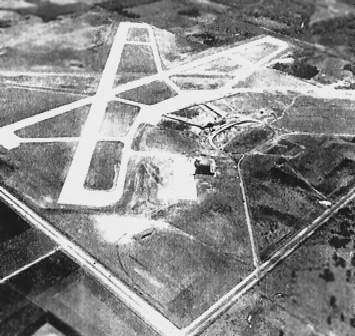

A 1951 aerial view looking southeast at Amon Carter Field (courtesy of Jerrell Baley) while it was still under construction,

with 2 runways having been completed, and a 3rd runway still being paved.

The American Airlines hangar (in the foreground) had been built, along with the terminal building.

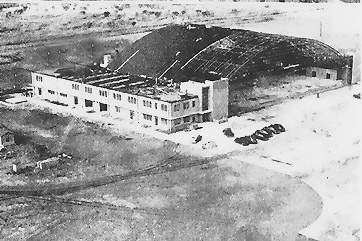

A circa 1951 photo of the Amon Carter Field terminal & control tower under construction.

In 1951-52, bond elections were held, and voters approved a total of $30 million in bonds for aviation improvements at Amon Carter.

Braniff & Delta leased 75 acres at GSW for hangars in 1952

(but ironically never ending up building any facilities on the property).

A 1952 photo looking southeast at Amon Carter Field while under construction (courtesy of Cliff Knight).

A 1952 photo looking northeast at the Amon Carter terminal under construction (courtesy of Cliff Knight).

A circa 1952 photo of the American Airlines hangar while under construction (courtesy of Cliff Knight).

An 11/14/52 photo by Bill Wood (courtesy of Jeff Switt) of the Amon Carter terminal & control tower,

taken shortly before the airport's opening.

An aerial view looking northwest at the crowd gathered for Amon Carter Field's dedication ceremony on 4/25/53.

Several twin-engine Douglas & Martin airliners are visible on the ramps.

When it was opened on 4/25/53, the new airport was christened Greater Fort Worth International Airport at Amon Carter Field.

The "International" title was a bit of wishful thinking - no scheduled international flights passed through Fort Worth.

Designers laid out the airfield with two 6,500' runways (17/35 & 13/31).

The footprint for a 3rd intersecting runway, oriented northeast/southwest, was cleared but not initially constructed.

Two large maintenance bases, for American Airlines & Fort Worth-based Central Airlines, were constructed as well.

The terminal was built on the west side of the field,

in the controversial location that had caused Dallas to pull out of the project in 1942.

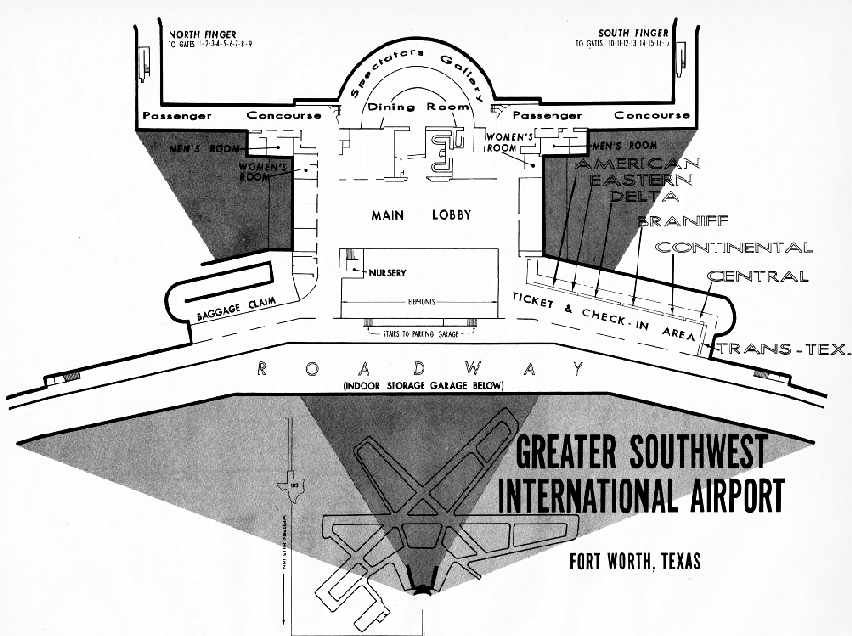

It was a 4-level structure topped by a control tower, flanked by twin 2-level wings & 2 concourses extending across the apron.

Ticket counters were situated in the southern wing, while baggage reclaim counters were in the north wing.

Between them was the lobby, a massive 2-story space furnished with plush furniture

and decorated with a bas-relief mural plated in 18-karat gold leaf.

The entire facility was designed in a southwestern art deco style,

and the grounds were lavishly landscaped with native Texas plants - live oak trees, yucca shrubs and cactus.

The 10 gates on the north concourse were used exclusively by American Airlines,

which was an ardent supporter of the airport & its largest carrier.

The other 4 airlines used the south concourse.

Passengers walked along the 2nd level of the concourse until they reached their gate,

where they took a staircase down to a ground-level departure lounge.

All of the scheduled carriers then serving Meacham Field (American, Braniff, Trans-Texas, Pioneer and Central)

transferred their flights to the new airport.

Meacham Field was downgraded to a general aviation facility, although it kept its FTW code.

The new airport was assigned ACF as its designator.

An April 1953 photo of Reeder, Thelin, Jackson, and Sattervashita at Amon Carter Field

(from the C.M. Thelin collection, courtesy of John Bradford).

According to John, “I think Jackson was the architect. Thelin is C.M. Thelin, the Public Works Director of Fort Worth, my grandfather.”

Note the B-36 bomber in the background on the right.

shows the massive B-36 bomber & Douglas & Convair airliners in front of the terminal.

Also note the Vought F7U Cutlass jet fighter behind the B-36's tail.

Mark McCauley noted, “In addition to the B-36 being built in Fort Worth, the Cutlass was built just down the road in Grand Prairie.”

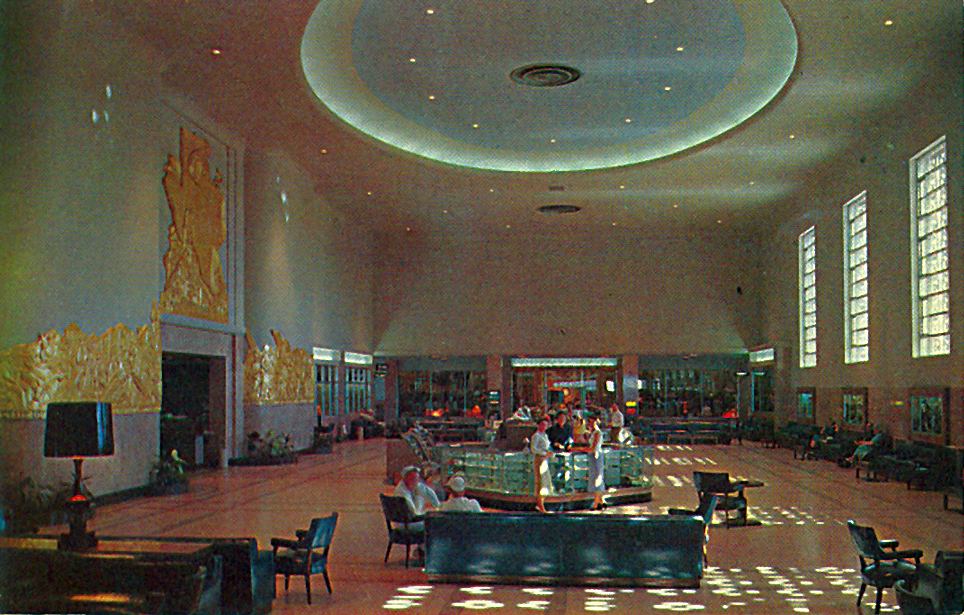

A circa 1953-54 postcard, depicting the beautiful Art Deco interior of the lobby

of the Amon Carter terminal building soon after its opening (courtesy Kristopher Crook).

The postcard's caption read: "The main lobby of the International Airport is colossal in size, being 60' x 180' with a 31' ceiling.

Finished in fine marble from Portugal & furnished in modern western style,

this waiting room offers comfort to thousands of travelers from all nations.

Surrounding entrance to main dining room, the celebrated mural portrays early Texas history culminating in the massive central scene.

The mural, done in bas-relief, is enriched with 18.5-karat gold leaf."

A circa 1953-54 postcard, depicting the dining room of the Amon Carter terminal building soon after its opening.

The postcard's caption read: "This famous bas-relief at Dining Room Entrance was executed by James Buchanan Winn, Jr.,

one of the most famous mural artists in the world.

The right pylon depicts Texas history from the Conquistadors to the surrender of Santa Anna to Sam Houston.

The left pylon depicts pioneer days with covered wagons, cowboys & Indians, pointing up to modern Texas and her industries.

The wand top of the Goddess of Flight is a six-inch star of diamonds & emeralds locating Amon Carter Field.

An acre of 18-karat gold leaf was required to cover the mural."

A circa early-1950s aerial view from a postcard, looking east at the terminal, control tower, and runways

of “Amon Carter Field, Greater Fort Worth International Airport”.

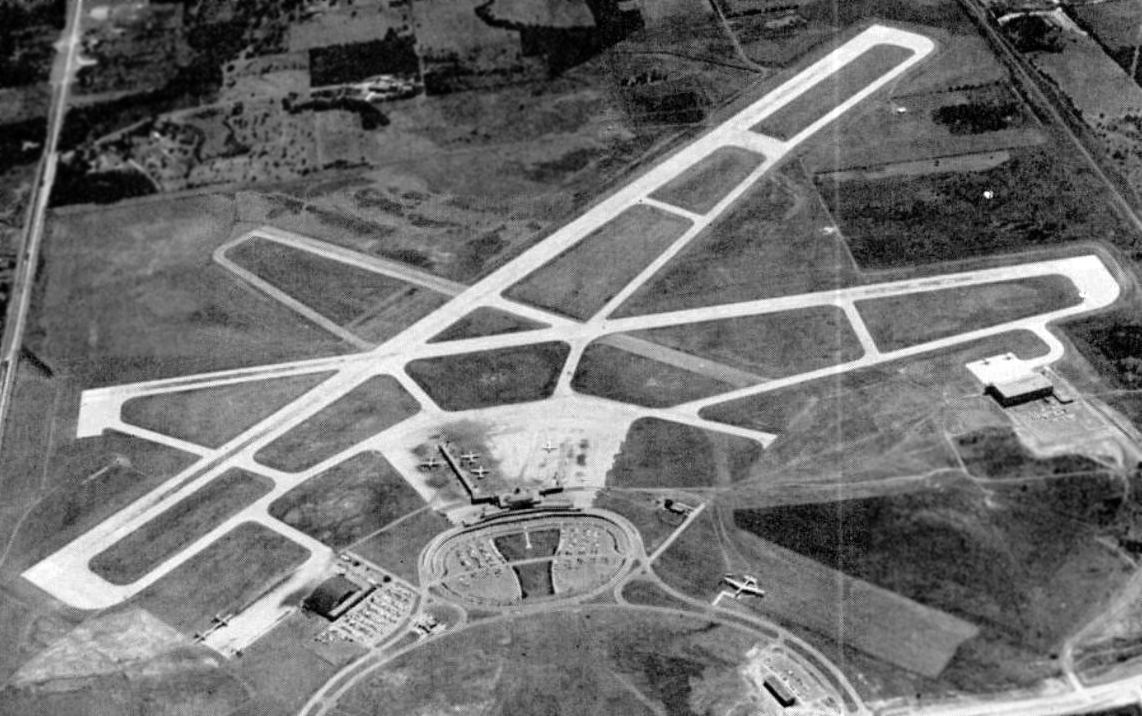

An aerial view looking northwest at Amon Carter Field, taken shortly after its 1953 opening.

For the first 5 years of its existence, the airport did very well.

State Highway 183, a major east-west road linking Dallas & Fort Worth,

was upgraded to 4 lanes, making access from either city quick & easy.

The airport's chief competitor, Dallas' Love Field, was still operating out of a 1940-vintage terminal,

and despite repeated additions it was unable to handle the traffic.

The Fort Worth airport, by comparison, was relatively congestion-free & easy to use.

The September 1954 DFW Local Aeronautical Chart (courtesy of David Brooks)

depicted Amon Carter Field as having 3 paved runways, with the longest being 6,400'.

A 6/24/55 photo of a 3 ½ year old John Weyrich at Amon Carter Field, in front of 2 DC-6s from American & Delta,

along with a photo of John in the same spot 60 years later.

John observed, “The window of opportunity to take that later photo closed soon after I took it.

The background horizon in the photo is now blocked by major construction at that location.”

According to drag racing historian Bret Kepner,

two different promoters gained permission to hold auto races on the runways of Amon Carter,

under the name Greater Southwest Dragway, from 1954-57.

Pioneer Air Lines merged with Los Angeles-based Continental Airlines in 1955.

Continental assumed all of Pioneer's flights from Amon Carter Field.

According to Chris Balducci, the 1955 movie “Strategic Air Command”

had a scene in which June Allyson was talking to James Stewart in a phone booth,

and “In the background was the old Amon Carter terminal!”

A 1956 aerial view looking south at Amon Carter Field (courtesy of Cliff Knight).

Note the 2 DC-3's in the foreground readying to take off on Runway 17.

If you look at the 2 finger concourses that shoot off the main terminal building,

the one on the north appears to be the only one used as seen by all the black on the tarmac.

The south concourse appears to not have been used at all.

This 1958 picture looking west (courtesy of Cliff Knight) shows both concourses completely full of aircraft.

Notice how much more use the southern concourse appears to have had

even 2 years after the above picture.

In 1958 Love Field opened a multimillion-dollar 'Jet Age' terminal building, then the largest in the nation.

Almost immediately, Amon Carter Field's share of passengers from Dallas vanished.

An undated view of the terminal building & control tower, from a vintage postcard (courtesy of Steve Cruse).

An undated photo of a Braniff Convair 340 in front of the terminal at Amon Carter Field.

Don Mackison recalled, “In the late 1950s... I boarded a Braniff flight at Love Field, and its first stop was at Amon Carter!

There were passengers carrying bags of groceries - on their way home after a day shopping?”

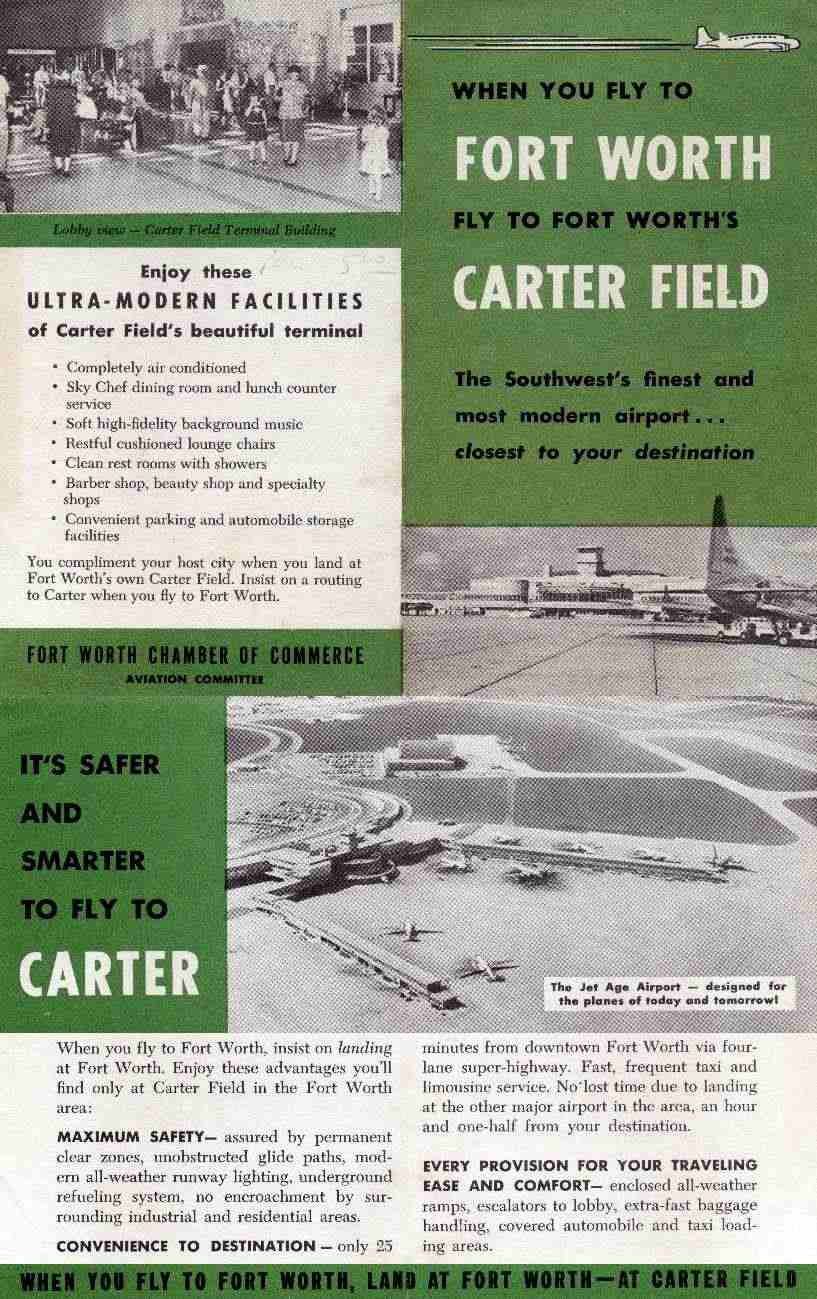

A late-1950s brochure by the Fort Worth Chamber of Commerce's Aviation Committee

urged passengers, “When you fly to Fort Worth fly to Fort Worth's Carter Field.”

During the 1950s two attempts were made by Fort Worth

to convert Carter Field into a joint regional airport with Dallas participating as a full partner.

Both efforts were rebuffed by Dallas, and expansion of Love Field continued.

An American Airlines Boeing 707 visited Amon Carter on a promotional flight in 1958.

American began scheduled jet service on the Fort Worth-Los Angeles route on 12/20/59.

A 1958 aerial view depicted GSW just before Runway 17/35 was lengthened,

and before the hangar was built on the southwest side of the field.

Note the 10 twin-engine Convair or Martin airliners parked on the taxiway leading to the northeast end of the northeast/southwest runway.

An undated aerial view looking northeast at the Amon Carter terminal from a 1959 postcard (courtesy of Charles Hall).

Charles recalled, “My first flight was from Ponca City, OK to Ft. Worth's Amon Carter Field, on a Central Airlines DC-3.”

The postcard's caption read, “One of the mot beautiful airports in the world,

this view accentuates the curved lines & color of the very functual [sic] terminal building.

The airport is also one of the safest in the nation, having long, clear approaches to wide concrete runways.

It is truly a 'jet age' airport, here today.”

Central Airlines built a hangar on the southwest side of GSW in 1959.

The 1959 USGS too map depicted “Greater Southwest International Airport”,

with the newly-built Central Airlines built a hangar on the southwest side.

While Braniff (the area's dominant carrier) kept only a token presence at Amon Carter,

American maintained a busy schedule at the airport well into the 1960s.

In 1960 Amon Carter Field was purchased by the city of Fort Worth

in an effort to compete more successfully with Love Field.

Michael Galloway recalled, “When I was 12 in 1960 after Houston I flew back home to Amon Carter Field in a DC-3 operated by Lone Star Airlines.

I believe this company either later became Braniff or was bought out by it.

That was my first time to fly & was quite impressed by the experience. I was in awe of both the aircraft & airport.

I remember being baffled by the subsequent abandonment of such a magnificent facility”

Amon Carter Airport, as depicted on a 1960 Humble Oil DFW road map.

Two new airlines joined the lineup at Amon Carter in 1961,

following route awards in the Southern Transcontinental Route case.

Delta Air Lines (which had served Dallas for decades) received authority to serve California via Fort Worth,

while Eastern Airlines was granted a Fort Worth-Dallas-New Orleans-Tampa-Miami route.

Passenger numbers at the airport were already starting to slide, as passengers and flights chose Love Field over Amon Carter.

An undated aerial view (from a 1961 article) looking southeast at GSW (courtesy of Jim Daigneau),

showing the massive runways & other facilities, but only 6 aircraft on the ramps.

Also note the huge B-36 bomber on display at bottom-right.

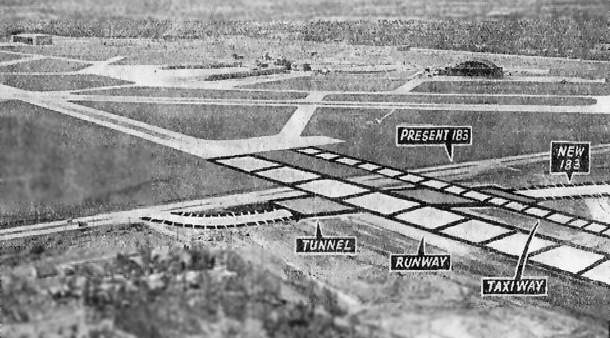

A 1962 photo looking southwest (courtesy of Cliff Knight), depicting the expansion of Runway 17/35 across Route 183.

At the time there are only 2 hangars visible in the picture.

The arched hangar at top right was the American Airlines hangar

and the square hangar at top left was Central Airlines.

By 1962 both Braniff & Delta still had leases on GSW airport property,

but both still had never built any facilities at the airport.

In 1962 the airport underwent its 1st & only expansion.

Fort Worth officials had abandoned their strategy of competing with Love Field,

and were determined to prove their airport offered unlimited expansion capability.

The airport obtained federal funds & extended both of its runways.

Runway 13/31 was lengthened by almost 2,000',

while Runway 17/35 was extended to the north in an ambitious project that required State Highway 183 to be rerouted through a tunnel.

The terminal building, already underutilized, was left alone - it was operating well under capacity.

In an effort to persuade Dallas to transfer operations from Love Field,

the airport's named was changed to the more neutral Greater Southwest International Airport-Amon Carter Field,

and the three-letter designator became GSW.

By that time, however, Dallas was unveiling a brand-new parallel runway at Love Field, effectively doubling its airport's capacity.

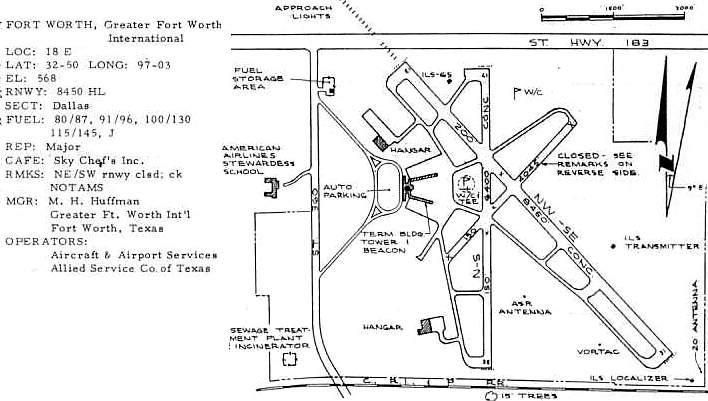

GSW was described in the 1962 AOPA Airport Directory

as having 2 concrete runways: 8,400' Runway 13/31 & 6,400' Runway 17/35.

The operator was listed as Allied Fueling Company,

and airline service was provided by American, Central, Continental, Delta, Eastern, and Trans-Texas Airlines.

The 1963 TX Airport Directory (courtesy of Steve Cruse)

depicted “Greater Fort Worth International” as having 2 paved runways: 8,460' Runway 13/31 & 6,400' Runway 17/35,

along with a closed northeast/southwest runway.

According to drag racing historian Bret Kepner,

two different promoters once again gained permission to hold auto races on the runways of Greater Southwest,

under the name Greater Southwest Dragway, from 1963-65.

A 1964 diagram of the Greater Southwest International Airport terminal building.

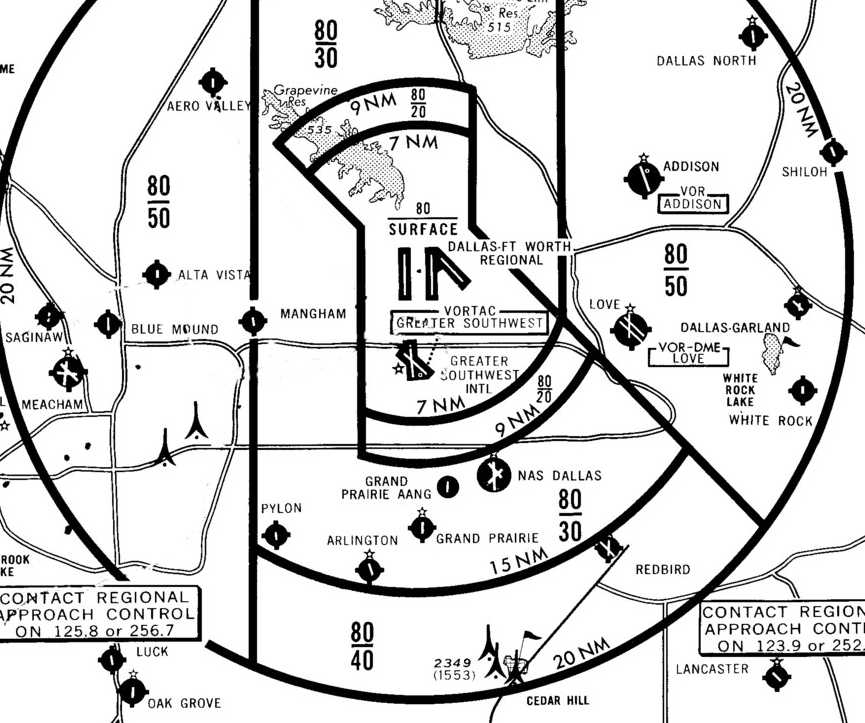

The 1964 DFW Local Aeronautical Chart (courtesy of John Price)

depicted Greater Southwest International as having 3 paved runways, with the longest being 9,000'.

Bob Wisne recalled, “I was hired in 1965 & spent 3 months at GSW Airport training as flight engineer on the DC-6 & DC-7.

The American Airlines maintenance hangar [was] where we attended ground school.”

Doug Johnson recalled, “I grew up in Hurst in the 1960s & early 1970s.

I was in the Civil Air Patrol (Apollo Cadet Squadron),

and our office was at GSW in the southeast corner of the main terminal building.

We had our meetings there weekly, sometimes 'camped-out' there & flew in & out of there,

also worked at the yearly Confederate Air Force Airshows that were held there, even got some rides in WWII aircraft there.

We knew a way to safely (and non-destructively) get into the giant B-36 out in front,

and spent many hours playing in it like we were on missions all over the world!”

Though Dallas & Fort Worth were arch-rivals,

FAA Chief Najeeb Halaby vowed his agency would not "put another nickel" into either of the cities' duplicate airports.

In 1964 the Civil Aeronautics Board ordered the 2 cities to come up in less than 180 days

with a voluntary agreement on the location of a new regional airport,

or the federal government would do it for them.

Both cities appointed committees, and by 1965 plans were set for a Dallas-Fort Worth Board.

The site for an airport, originally called Dallas-Fort Worth Regional Airport, was chosen, just northeast of GSW.

A circa 1965 photo by Gary Jones of an American Airlines Lockheed Electra on final for GSW over Highway 183.

A circa 1965 photo by Gary Jones of the Convair B-36 bomber on display at GSW, with the terminal visible on the left.

A circa 1965 photo by Gary Jones of the nose of the “City of Forth Worth”, the Convair B-36 bomber on display at GSW, with the terminal visible in the background.

By 1965 the percentage of enplaning passengers from Greater Southwest

had declined to less than 1% of TX air traffic (compared to 6% in 1959),

while Love Field had increased from 40% to 49%.

The result was the virtual abandonment of Greater Southwest International Airport

and serious congestion at Love Field.

A 1967 photo by Bob Garrand of a Central Airlines Douglas DC-3 at Amon Carter Field.

"This DC-3 had been flying 30 years already when seen here with the engines removed

(notice the sand bags on the wing & tail to compensate)."

By 1967 almost every long-haul route out of GSW had been axed,

leaving only a few tag services to Texas cities, along with American's lone daily flight to Los Angeles.

Most flights required a brief stopover at Love Field, defeating the purpose of using GSW altogether.

Hometown carrier Central Airlines was absorbed by Denver-based Frontier Airlines,

which suspended Fort Worth services almost immediately.

Central's GSW hangar & headquarters building were shuttered as well.

A December 1967 aerial view looking south at GSW (courtesy of Jerrell Baley),

showing the massive runways & other facilities, but very few aircraft on the ramps.

Also note the huge B-36 bomber on display just beyond the parking lot.

Ground was broken for the Dallas-Fort Worth Regional Airport in 1968

at the intersection of the towns of Euless, Irving, and Grapevine.

In 1968 GSW's airlines petitioned the Civil Aeronautics Board to cease their passenger services at GSW immediately.

With construction finally underway on a new regional airport just north of GSW, the CAB reluctantly granted the request.

By the end of the year, only American was still providing service, and by 1969 they were gone too.

With the scheduled traffic gone, GSW settled into a role as a reliever airport for Love Field,

handling charter flights, commuter/air taxi traffic, and crew training flights.

Flight academies & general aviation companies took up residence in the terminal building,

occupying the former ticketing & baggage claim wings.

GSW's struggling restaurant & gift shop hung on somehow,

catering to the local employees & occasional charter passengers who occasionally passed through.

American Airlines continued to use its hangar on the north side of GSW for maintenance,

even after passenger flights had been withdrawn.

Ed May recalled, “I remember that airport well, and took much of my Private Pilot training there in a Cessna 150 in the summer of 1968.

It wasn’t uncommon to be in the pattern with a 727 or 2, and I remember some really long downwinds, running at full throttle to stay out the big guys way.

I remember walking down the long, empty, echoing hallways of the terminal wings to get to the little flight school office out at the end,

where the handful of 150s & 172s were parked on the huge, empty ramp.

It was a really cool place, and a shame that such a fine terminal, a monument to classic Art Deco style, was destroyed.

There was a helicopter flight school there at one time, and the joke was that it was the only heliport in the country with a 9,000' runway.

Around 1970 I saw the first 747 (City of Everett) arrive there, and people marveled at the 'Aluminum Overcast',

which could only be parked at a certain spot on the ramp that was strong enough to bear its great weight.

But that was different era, when people dressed up to fly on airliners, and there was no-one searching you before boarding.

When people actually went out on the balcony to watch DC-7’s and Connies take off & land.”

Dan Kinney recalled, “In the 1960s & 1970s we lived in Irving -

I vividly remember how busy the local pattern there was with American Airlines aircraft

particularly the DC-10 which American was hard at work transitioning pilots into that bird.”

Greater Southwest International Airport was still depicted as an active airfield

in the 1970 TX Airport Directory (courtesy of Ray Brindle).

According to Earl Wycoff (retired Delta Airlines pilot), "I had the experience of actually working at [GSW]

from about October 1970 to March of 1971.

There was a small flight school which had taken up residence in the far south end of the terminal arc

and we flew about 6 light aircraft.

I know there were several Cessnas & Pipers, but it has been so long ago I can't remember the exact details."

A 1970 aerial view showed that the number of airliners stored on the northeast taxiway had increased to 19,

roughly split between twin-engine & 4-engine airliners.

A 1971 view from inside Amon Carter's control tower, with some low-tech equipment inside, and a hangar & a 707 & 2 DC-6s to the north.

A 1972 aerial view showed 5 aircraft parked outside of the Central Airlines hangar on the southwest side of GSW.

Earl Wycoff recalled, "Braniff, American, and Delta all used the Greater Southwest ILS facilities for training flights,

and on 5/30/72 there was a crash at the airport which revolutionized thinking in the industry about the importance of wake turbulence.

There were 2 aircraft in the pattern: an American DC-10 & a Delta DC9-30.

The wind was from the northwest, but the ILS was aligned to the southeast,

so they were making approaches to Runway 13 with a 7-10 knot tailwind.

On the final pass, the Delta DC-9 was about 3 miles behind the American DC-10.

As they approached the end of the runway, they encountered the wake turbulence from the DC-10.

The roll component was so strong that the aircraft uncontrollably rolled to about 70 degrees,

struck a wing tip & cartwheeled.

All aboard [3 pilots & an FAA inspector] were killed.

The resulting investigation resulted in the 'heavy' aircraft designation & the rule of 5 miles in trail behind a 'heavy'.

It truly was a shame that such a grand airport was allowed to languish

largely because of the animosities of Dallas leaders to Amon Carter & the returned feelings."

A 1972 aerial view showed that the number of aircraft stored on the northeast taxiway

had sharply decreased within 2 years to only 3 planes.

All of the 4-engine airliners were gone.

A closeup from the 1972 aerial view showed that all of the airliners were gone from the terminal,

with the somewhat unusual sight of a smattering of general aviation aircraft being the only aircraft around the terminal.

The last aeronautical chart depiction which has been located of GSW was on a 1973 DFW Terminal Control Area Chart (courtesy of Fred Fischer).

Mike Martin recalled, “My flight engineer checkride in the 727 departed Dallas on a night in December of 1973,

making our touch-and-goes at GSW on Runway 35 before returning to Love Field.”

GSW was permanently closed on 1/13/74,

when the new Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport opened just to the north.

With DFW's flights now taking off & landing immediately overhead,

the FAA ordered GSW's runways closed as a safety precaution.

Matt Osterberg recalled, “For the opening of DFW [1973], my roommate decided he had to witness the dual landings of the Air France & British Air Concordes.

Since we didn’t have VIP status, GSW seemed promising. It was eerie to say the least.

Wide open, deserted & explorable. Everything was there but covered in dust.

A singular 'Twilight Zone' day. Even my memory is in black & white.

We walked the length of the concourse & out onto the tarmac: Wham!

The Goodyear blimp hovering a few feet above. Almost within arm’s reach.

No one was on the ground, so I don’t think it was a staging area. Just killing time?”

George Singleton recalled of GSW, “As the airport was in the process of being demolished,

a B-25 was still parked along one of the concourses.

The owner was given a very short time to have it removed.

As I understand it, the plane was made flightworthy & departed, maybe the last flight out of Greater Southwest,

but developed engine trouble & was put down out in the country before it reached its intended destination of Paris, TX.

My parents do remember it being on the news at the time in Fort Worth.”

The massive GSW airport facility sat completely abandoned throughout most of the 1970s,

as officials wrangled over what to do with the site.

A 1974 photo by Tim Burpo of cars which were raced on GSW's abandoned runways.

Tim recalled, “We raced a car there in 1974 just after it closed.

A friend of mine & I used to go out there after school & play around on the abandoned planes,

and we would take the mufflers off his car & blast up & down the runway doing 120 mph,

before they hired security guards to run everybody off.”

A 1975 photo by Brian Lusk of the former American Airlines maintenance hangar at GSW.

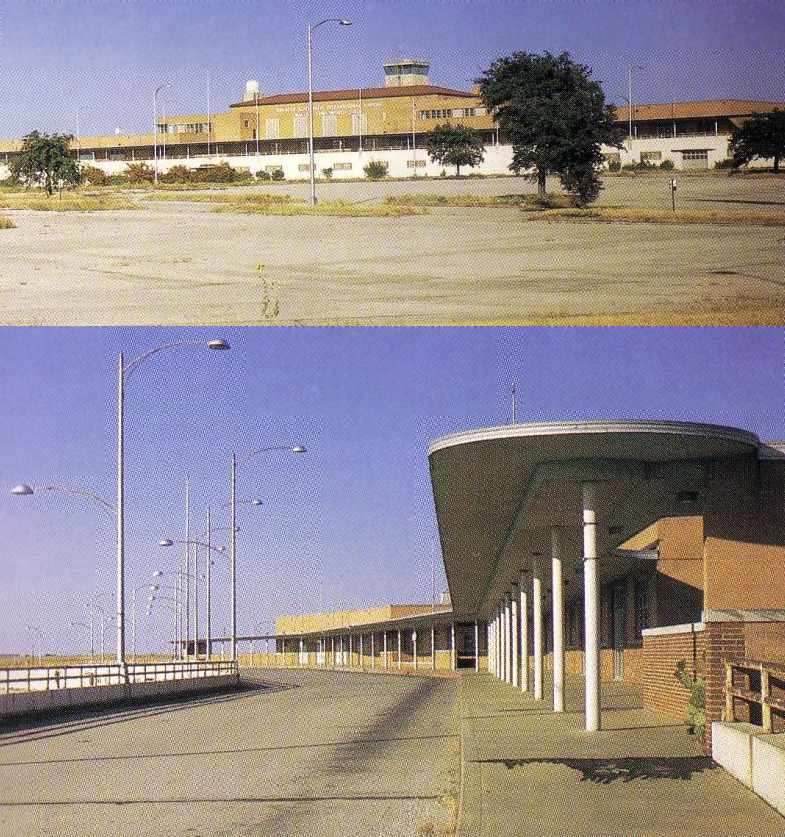

Two 1975 photos by Brian Lusk of the abandoned terminal at Amon Carter Field.

Carlos Amador reported his father "was a Pilot for Braniff & later ended his career flying for CP Air.

I remember standing with him at the old Greater Southwest Airport in front of the empty terminal building

and all he said was, 'What a shame.'

Aviation history is dying, there are no great old terminals left."

The last photo which has been located showing an aircraft at Amon Carter Field was an April 1976 poto by Carl Jenkins of N989C, a North American TB-25N Mitchell, 44-29127.

The last photo which has been located showing the GSW terminal building was a May 1977 photo by Dan Davis.

Kerry Crawford recalled, "I also worked at Greater Southwest Airport for a couple of years after it closed.

There was a 'phantom' of the airport for a while.

He would elude police in the maze of tunnels underneath. They never found him.

Another time in 1978, someone broke into the tower with a rifle & was shooting at cars on the highway.

Didn't get much press back then.

It would have been blasted across the country if it happened now."

The last photo which has been located showing GSW before the massive runways were removed was a 1979 aerial view.

Steve Harkins recalled, “I attended some SCCA sports car regionals there in 1979,

where I saw the actor Paul Newman working on the crew of one of the cars competing (a Formula Ford, I think).”

Joe Castleman recalled, "My family & I moved to the area in 1979,

at which point there were still several remnants of GSW.

The old American Airlines hangar actually outlived the airport by quite a few years,

as it was converted into AA's Reservations center.”

In 1979 the land was sold to a developer, who renamed the area CentrePoint & began marketing it as an office/industrial park.

The terminal was demolished in 1980.

According to Bob Van Hemert, pictures from the University of TX at Arlington show the “the demolishing of the airport in August of 1980.”

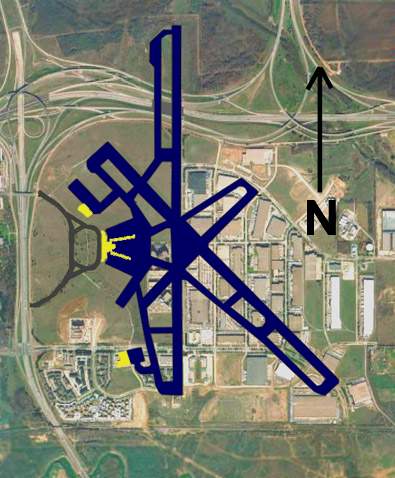

As depicted on the 1981 topo map,

the GSW airfield ultimately consisted of 3 concrete runways (the largest, 17/35, was 9,300' long),

taxiways, ramps, hangars, and a large semi-circular passenger terminal.

It was a very large facility by any measure.

All of the former GSW runways (except a small portion of one runway) had been removed by 1982.

Joe Castleman recalled, "I think I remember seeing the old [American Airlines] hangar up through 1986 or so.

At the point we moved to the area, we used a rental car agency whose office was adjacent to this old terminal.

After GSW closed, Runway 18/35 quickly became Amon Carter Boulevard,

but it was many years before it was properly re-paved as a street

(AMR's headquarters are now situated along this street).

The old highway tunnel which used to pass under Runway 17/35 was not

demolished until 1989 or 1991 (can't remember exactly, but it was one of

the 2 summers that I was home from college).”

Joe Castleman continued, “I'm not exactly sure when the American Airlines Flight Academy & Learning Center were built,

but one or both preceded the construction of DFW (and AA's relocation there).

I don't know if this was in anticipation of DFW being built,

or if there was simply more room next to GSW as opposed to Love Field or some other urban airport.

Likewise, the nearby FAA complex is older than DFW,

and I assume they picked the site as a midpoint between Meacham & Love Fields.

I also seem to remember that several DC-8s were mothballed there, after AA purchased Trans-Caribbean."

Although millions of taxpayer dollars had been spent to build runways & passenger terminals at GSW,

not a bit of that infrastructure was reused as part of the new DFW airport, or even for any other purpose.

It was all plowed into the ground,

removing any tangible reminder of previous failures to achieve compromises between Dallas & Fort Worth politicians.

Even the elaborate terminal building (with its gold-leaf murals) was not allowed to remain standing.

It was all plowed into the ground,

so that the site could be "reused" (!) as an empty grass field for the next 30 years.

The primary reason for this seemingly needless action was simply to remove any trace from the public's eye

that the facility had ever existed in the first place.

As seen in the 1995 USGS aerial photo,

the outlines of the former Runway 13 could still be perceived in the grass areas in the middle-left of the photo.

To gain an appreciation for how the former airport was laid out relative to the site's current configuration,

Cliff Knight overlaid the former airport layout on the a 2000 aerial photo.

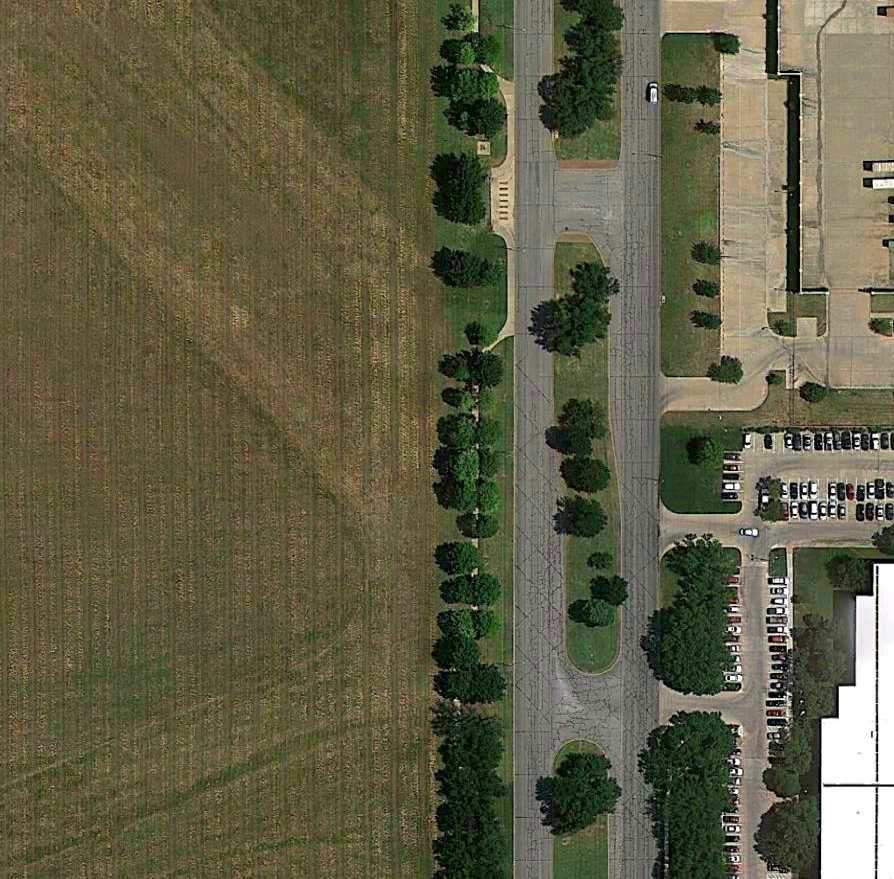

A 7/02 aerial photo by Paul Freeman looking west at the site of GSW,

showing the remaining portion of Runway 17 & its adjacent taxiway & runup pad.

A 7/02 photo by Paul Freeman looking north along the only remaining runway segment -

a 1,600' portion of Runway 17.

A 7/02 photo by Paul Freeman looking north along the remaining segment of Runway 17's parallel taxiway.

A 7/02 photo by Paul Freeman of what used to be the northern entrance to Greater Southwest International Airport, now a dead-end.

An uninformed observer would never know that this empty grass field

used to contain the terminal & runways of an international airport.

The line of trees along the right side form an arc -

they used to line the circular entrance road to the airport terminal.

Photo by Paul Freeman 7/02.

Paul Freeman visited the site of Greater Southwest International Airport in 2002.

It is located southeast of the intersection of Route 183 & Route 360.

It is an eerie sight - thousands of commuters drive by on Route 360,

most likely without realizing what used to exist on what is now a totally empty grass field.

Nearly all of the airport infrastructure (runways, terminal building, etc.) has been completely removed.

As of 2002, the majority of the former airport property remains as an empty grass field,

and signs on the property describe plans for a future office development called CentrePort.

Clues to its previous role abound, though.

Two rows of trees form an arc extending from Route 360 -

a comparison with the above 1981 topo map shows that these are the same trees

which used to line the circular entrance road to the airport terminal.

In the area that used to contain the terminal, all previous pavement, foundations, etc., have been removed.

The only tangible remains are a few concrete footings (for lightpoles?)

which remain scattered throughout the grass field.

Strangely enough, the only intact piece of the once-extensive airport is a 1,600' portion of Runway 17

(along with a runup pad & a portion of taxiway),

which still exists extending north from Route 183.

The remainder of the former runway (extending to the south from Route 183)

has been reused as Amon Carter Boulevard.

An eloquent set of observations was sent in by Dallas resident Steve Anderson:

"I grew up near there as the place metamorphosed from airport to training center,

to used aircraft sales lots, to airplane graveyard."

Anderson reminisces about climbing around all of "the derelict aircraft that had been rolled onto a grassy area

off of a taxiway in what was, at the time, the southwest corner of the airport.

They had some good wrecks there, and they sat there for years oxidizing in the sun & humidity,

waiting for the scrap dealer to come, I have no idea why so long.

The best preserved was an old Convair transport, I'm not sure of the model but I think it was like a C-240.

My friend & I could crawl in there & actually sit in the pilot's seats & play with the controls.

Apparently this ship had no hydraulic or electric boost because I could move the pedals,

which were still cabled to the rudder & I could make it move & hear the pulleys spinning under the deck.

It was better than Disneyland for me. I have never forgotten that plane.

I can even remember the way it smelled, and the ashtrays(!) that were built right into what was left of the instrument panel.

Most of the gauges had been removed.

Anyway, I thought it was a hell of a lot better than a treehouse."

Anderson continues, "When I returned to the DFW area it was gone.

It was not merely closed completely,

it was as if God had pulled out almost every artifact & buried it in a landfill somewhere. I was aghast.

I sure do wish that the marble, the murals, and the old bank-style art-deco ticket counters

inside that terminal building could have been saved somehow.

For years a person could walk through that building & admire the grand things there

as well as visit the handful of struggling businesses,

including a bar & a diner, that were still hanging on somehow.

It was truly as if they built this beautiful airport & nobody ever came,

and for a long while it was kept up real nice, as if somebody was sure that people would be coming back,

planes would land here again,

and those polished marble & brass-fitted ticket cages would once again

be occupied by clerks selling tickets & checking bags."

Anderson continues, "The thing that disturbs me the most about it,

besides the wastefulness of it all & the apparent 'who cares' attitude of the average person,

is the fact that there is absolutely NOTHING there to commemorate the place.

No plaque, no signage, no Texas Historical marker, nada.

That is incredible, and unacceptable.

When I retire one of the things on my to-do list will be to find out what it takes to get the state to erect a plaque on a site.

Whenever I drive by there I can almost hear the radial engines roaring

and I recall what it was like to be served a meal (in coach!) on real china with silverware...."

Well said, Steve!

A December 2003 aerial view by Travis Church looking southwest at the remaining section of GSW's Runway 17,

with the former terminal area in the background.

Note the “@” symbol which is kept mowed in the grass just beyond the highway.

According to Clark Vinson, “The company that bought the property where GSW used to sit markets itself as The Campus @ CentrePort.

My guess is they are the ones who mow that [@] into the grass.”

Ken Holmes reported in 2005 that “the [American Airlines] flight academy is designated as GSW.

When pilots go to the flight academy for their training, the payroll & travel data lists them at GSW.

I often wonder how many people know it stands for a defunct airport.”

As seen in a 2006 aerial photo,

the outlines of the former Runway 13 could still be perceived in the grass areas in the middle-left of the photo,

and the northern end of Runway 17 also still remains intact.

David Jefferson reported in 2006, “I have some bad news about Amon Carter / Greater Southwest International.

I sit on a city board that reviews development plans

and a proposal has just come in that will do away with the open grass area

and tree line that marks the location of the old terminal building driveway.

I suspect that fairly soon the last vestiges of the airfield will be gone

(except for the small remaining piece of the runway extension that was left on the north side of Highway 183).

I now live about 10 minutes from the site & wish I could put it all back, but time marches on.”

A circa 2006 aerial view looking east at the only building from Greater Southwest International Airport which remains standing -

the former pumphouse, located just south of the former terminal building.

The top of the underground fuel tanks is visible to its right.

A 6/12/11 aerial photo (courtesy of Devan Mayer) of an amazing remnant which remains at the site of Greater Southwest International Airport:

the diagonal markings visible on Amon Carter Boulevard (the former Runway 17/35) just north of Sovereign Road

are actually the expansion joints of the former Runway 13/31.

For confirmation note the telltale signature of the Runway 13/31 alignment extending in the grass field to the northwest.

Nearby resident Philip Putnam observed, “I had no idea that an airport of such consequence had sat there.

I'm one of those who drives by that site all the time, with zero clue of what had been there.

I'm stunned that the mural wasn't removed, or that the terminal building wasn't preserved by the developer.

In an area where aviation is such an integral part of our history & growth,

an old art deco terminal like that would be incredible as a museum... or even office space.

Why demolish it? I don't get it. It's not like anyone's been clamoring to build at CentrePort.”

A 4/2/14 photo by Tekang Wang looking north along the remnant of Amon Carter Field's Runway 35 “through the chain-link fence. Looks like police training activity of some sort.”

A 4/2/14 photo by Tekang Wang looking southeast at the Amon Carter Field airport entry.

Tekang observed it is “Still mostly empty, although the southern half of the field is beginning to fill with apartment buildings.”

Thanks to Douglas Wright for pointing out this airfield.

See also:

The Special Collections Division of the University of Texas at Arlington Libraries.

http://www.tsha.utexas.edu/handbook/online/articles/view/DD/epd1.html

http://www.dfwairport.com/visitor/history.htm

…………………………………………..……………………………………..

A 7/02 photo by Paul Freeman of the "Flagship Knoxville", a vintage restored DC-3 airliner,

at the American Airlines Museum across the street from the site of Greater Southwest International Airport.

The Corporate Headquarters of American Airlines has been built over the southeast corner of the site.

American Airlines also operates a very nice little aviation museum directly across Route 360 to the west.

Ironically, even though the museum faces the site of the former airport,

its exhibits contain not a single mention of Amon Carter Field.

When a museum guide was asked if they had any information about the former airport,

the replay was a polite, "I'm sorry, but I don't know much about it."

Scott Turner reported in 2014, “I made it a point to walk the grass fields of GSW & visit the [American Airlines] Aviation Museum.

After reading about GSW, I wanted to do something in memory of all who knew & flew GSW.

I have plans to build a scale model/diorama of GSW. It would be at my own cost.

I approached the Aviation Museum about building the model & displaying it in the museum.

I was politely refused & told that there would not be enough room (4'x8'?) for such a display.

I also followed up on a possible historical marker or commemorative monument, but to no avail.

It's as if the powers that be truly do not want this grand facility to be remembered.

Maybe some day the museum would reconsider my offer.

It would cost them absolutely nothing except a little space & a dollar's worth of electricity for the lighting.”

…………………………………………..……………………………………..

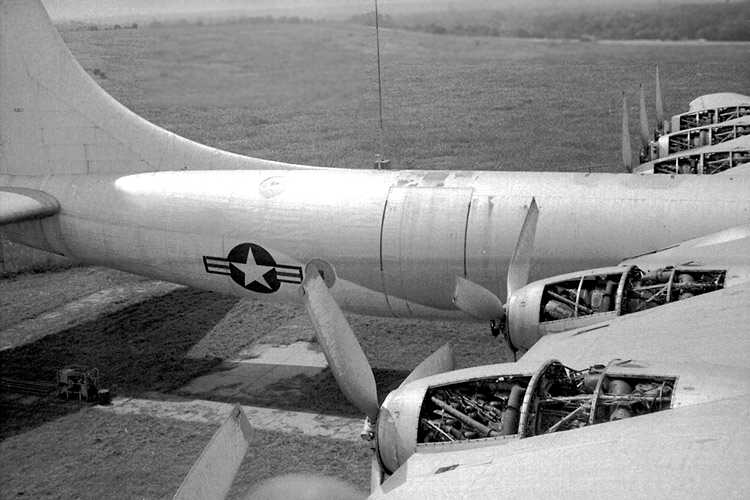

The very last B-36 Peacemaker produced, guarding the entrance to GSW in 1970.

An interesting sidebar to the history of GSW concerns its "gate guardian".

For many years, the entrance to GSW was graced by an enormous B-36 Peacemaker bomber on static display.

This particular B-36 was the very last one to roll off the Convair assembly lines at nearby Carswell Field.

In 1959, a mere 5 years after it was delivered brand-new to the Air Force,

the last B-36 made its final flight back to Fort Worth as part of an operation officially nicknamed "Operation Sayonara".

The Air Force at that time loaned the plane to the city of Fort Worth,

to be placed on permanent display at Greater Southwest International Airport.

Now officially named "City of Fort Worth",

the plane was rolled across a grassy field on heavy steel matting & placed on display

adjacent to the entrance to the airport terminal building

in a memorial park that was constructed & donated by the Amon Carter Foundation.

Members of the Convair Management Club & hundreds of Convair employees volunteered

their services & their time to prepare the plane for display.

Several thousand people toured the plane during the following years.

Ed May recalled, “My father & I were at Amon Carter Field in February 1959,

when that airplane, the City of Fort Worth, #385 & the last built, was delivered from Carswell Air Force Base across town to be a gate guard.

My dad knew someone on the crew, and we got to go aboard the still-warm bomber; the R-4360s still tinkling as they cooled.

This 7-year old was whisked through the 80' tunnel between the forward & aft compartments on the little trolley,

whooping the whole way, and probably sparking a life-long love of aviation.

Some friends & I once got caught exploring the B-36

(we climbed up the left main gear strut, where there was an opening in the cyclone fence you could wiggle through

and gain entry to the fuselage through the wing root access hatch) and took pictures of the thoroughly-vandalized interior.”

A 1970 aerial view of the B-36 parked beside the southwest entrance to GSW Airport.

As it sat for many years at GSW, the B-36 eventually became home for many birds as it baked in the hot Texas sun.

Vandals broke into it many times & inflicted heavy damage to the interior & the flight deck.

A 1972 photo of the B-36 at GSW, with all 6 engine nacelles exposed for restoration.

After hosting thousands of visitors for the next 10 years,

the plane was evicted from its park due to closing of GSW.

Of the different plans suggested for its rescue,

the most ambitious was made by Sam Ball, a Convair aeronautical engineer.

He proposed the plane be restored sufficiently to allow it to fly to nearby Meacham Field,

where it would be further restored & maintained as a flying museum.

The Peacemaker Foundation was established to achieve this goal,

and Ball received permission from the City of Fort Worth to restore & fly the plane.

Severe damage to the cockpit & instruments,

inflicted by vandals who ravaged the plane with fire axes & hammers,

was a major impediment to the flyout attempt.

Only one complete set of engine gauges survived the carnage,

and they had to be rewired to each engine in turn as they were started.

Work progressed while a world-wide search for instruments was undertaken.

All six piston engines were started before the project was halted.

One engine was allowed to run for 15 minutes,

and operated flawlessly after sitting idle for nearly 12 years.

None of the 4 jet engines were restarted.

Alarmed by the possibility of the plane becoming airworthy,

the Air Force decreed that work cease on the flyout effort.

They explained that the plane would be a threat to national security,

and would be a huge safety hazard if allowed to operate under civilian control.

Their announced plan to repossess the bomber launched a long series of negotiations with the City of Fort Worth,

who came under intense local pressure to save the plane.

During the next 2 years, work on the plane scaled down while negotiations continued with the Air Force.

The work performed was primarily to repair vandalism that had inflicted heavy damage to the plane.

The search for instruments continued & intensified by some,

as many other disheartened volunteers drifted away.

Steve Harkins recalled, “In the mid 1970s I went to Great Southwest Airport

to meet with the guys who were trying the restore the B-36 parked there.

The plane was in pretty sad shape then, with birds nesting inside the wings

(they had pieces of chain link fence covering the wheelwells to keep people out of them) and the horizontal stabilizer.

The cockpit gauges & Norden bombsight had been pretty much destroyed by vandals (except for the gauges that had been stolen).”

With time running out due to the 1974 closing date set for the GSW runways,

a valiant last effort was made to fly the plane to a new location.

The Air Force hinted that, under the right circumstances, it might grant permission for a single short flight.

This raised hopes that a future exception might also be received for additional flights.

so a scramble for volunteers, money, and qualified flight crews ensued.

Several B-36 qualified pilots were located & asked to fly the plane if they were selected to do so.

Beryl Erickson of Aspen, Colorado, the first man to fly a B-36, agreed to fly it if he was chosen.

Erickson observed that if a flight any longer than the 3 miles to DFW were contemplated

the plane would have to be virtually completely restored beforehand.

Key to the success of Ball's venture was obtaining title to the plane from the Air Force & locating a suitable site for it.

The managers of Fort Worth's Meacham Field by this time were reluctant to have the bomber

because they were having a space problem & were even trying to get rid of a derelict PBY.

The new managers of the soon to open DFW Airport were simply too busy to be bothered with it.

The Air Force steadfastly refused to transfer the plane's title to a civilian group,

and as a result, the Peacemaker Foundation failed to receive tax-exempt status from the IRS.

This proved to be the death knell for the Foundation as donations stopped & volunteers quit the project.

The B-36 parked in front of the closed terminal of GSW in 1976,

missing 2 of its left-wing engines & propellers.

With backing from the DoD, the Air Force repossessed the bomber from the City of Fort Worth,

again claiming that if it were operational it could be stolen & used for terrorist attacks on nations to our south.

They cited the lack of secure (guarded) storage of the operational strategic bomber

as one of many reasons for not wanting it to fly.

Custody of the plane was then transferred to the new Museum of Aviation Group (MAG)

that was negotiating with DFW Airport for space to display the plane.

MAG's volunteers worked quickly to move the plane from Peacemaker Park.

Facing threats from the City of Fort Worth to scrap the plane,

MAG moved it a short distance to a concrete apron adjacent to GSW's terminal building.

Negotiations for display space at DFW failed,

and MAG located a new site just outside the south gate of General Dynamics (formerly Convair),

and named it Southwest Aerospace Museum (SAM).

After the plane was moved in 1976, it was reassembled & displayed at the Museum of Aviation Group's site.

Mag's directors later voted to dissolve MAG, and incorporated the Southwest Aerospace Museum (SAM).

In the years following the plane's reassembly & display at its new home, more hard times befell it.

Lack of maintenance allowed further deterioration,

and then, with the closing of Carswell AFB, the number of visitors to the site dwindled.

It was suggested the plane might eventually be scrapped if it was not again rescued.

In 1993 a new group was formed to save the B-36.

With support from the City of Fort Worth,

it was moved into a hangar at the bomber plant, now operated by Lockheed Martin.

It was waiting to be moved to a new Aviation Heritage Museum to be built at Fort Worth's Alliance Airport.

Bobby Mills reported, “In 2005, the Aviation Heritage Museum was forced by the U.S. Air Force

to release the B-36 because a suitable home could not be found for it.

The foundation could not raise enough money to build a museum at Alliance Airport north of Fort Worth.

The B-36 has since been sent to The Pima Air & Space Museum in Tucson, AZ,

on loan from the National Museum of the United States Air Force.

It was sad to see it leave. I was born in Arlington & have lived here ever since.”

As of 2006 Chris Kennedy reported that the B-36 “Spirit of Fort Worth”

was under restoration/re-assembly at in Tucson, AZ.

____________________________________________________

Denton Field / College Field, Denton, TX

33.26, -97.144 (North of Dallas Fort Worth Airport)

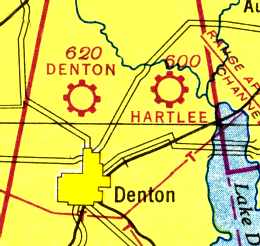

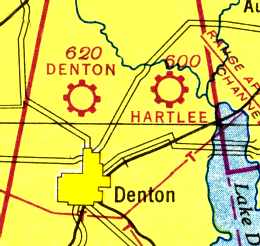

Denton Field, as depicted on the 1944 Dallas Sectional Chart (courtesy of David Brooks).

Photo of the airfield while in use has not been located.

Note that Denton Field is distinct from both the pre-WW2 Denton Municipal Airport (3/4-mile northwest of the town of Denton),

as well as Hartlee Field (3 miles to the east of Denton Field).

According to the Handbook of TX, Denton Field was the site of the North Texas civilian pilot-training program

of the Civilian Aeronautics Authority starting in 1940.

The original purpose of the program was to aid in the proper instruction of private flyers,

but after World War II began, the program emphasized preparing young men for military flying.

Colonel Ralph Devore, director of Region 4 of the Civilian Aeronautics Authority,

selected Denton as the site for the region's North Texas base,

and construction was begun & was completed during the summer of 1940.

The program at Denton began on 10/10/40,

with Theron Fouts as director, C. S. Floyd as flight instructor, and Fred Connell as ground instructor.

Denton Field's program accepted young men between the ages of 19-26

who had completed one year of college & could pass a medical examination.

Each student received 72 hours of ground training & 35-45 hours of flying, half flown solo.

In the fall of 1940 twenty students enrolled in the program.

The following year that number increased to thirty-five.

The earliest depiction of Denton Field which has been located

was on the 1942 Dallas Sectional chart (according to Chris Kennedy).

From 1942-45 an average of 33 students graduated each academic year.

The April 1944 U.S. Army/Navy Directory of Airfields (courtesy of Ken Mercer)

described Denton Field as having a 2,500' unpaved runway,

and indicated that Navy flight operations were conducted from the field (?).

The orientation & number of Denton's runway(s) has not been determined.

Denton Field was not listed among active airfields in the 1945 AAF Airfield Directory (courtesy of Scott Murdock).

At the end of the war in 1945 the civilian pilot-training program ended & Denton Field was reportedly abandoned.

However, the airfield may have continued to see some use for a short period of time under a new name,

as the 1945 Dallas Sectional Chart (courtesy of David Brooks)

depicted the airfield under a new name, "College" Field.

It was also depicted as "College" Field on the 1945 Wichita Mountains World Aeronautical Chart (courtesy of David Brooks).

College Field was apparently abandoned at some point between 1945-47,

after a new Denton Municipal Airport had been constructed (4 miles southwest of the town of Denton),

as only the new airport was depicted on the March 1947 Dallas Sectional Chart (courtesy of Chris Kennedy).

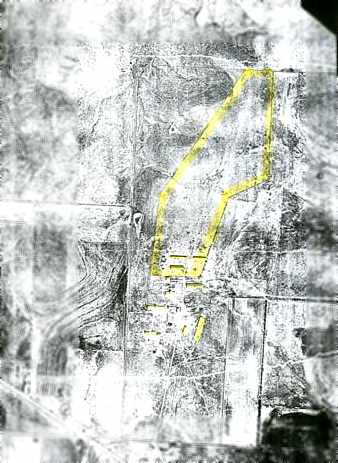

A 1958 aerial photo of the site of College Field (courtesy of Chris Jackson).

The fence line that enclosed the airstrip & some of its buildings are highlighted.

The outline of the single northeast/southwest runway was still barely recognizable.

The Army later selected the area around Denton Field as the site of Battery DF-01,

one of 5 Nike-Hercules surface-to-air missile batteries which defended the Dallas-Fort Worth area.

The Control Site for Battery DF-01 was constructed in 1959 adjacent to the northeast side of Denton Field,

while the Launch site was located a mile further north.

Chris Jackson reported, “The servicemen from the Nike base believe that the Army purchased the land for the missile base

from a woman who owned much of the surrounding land (but not the airfield).

They have told me a number of stories about how hostile the woman was,

as she evidently resented them building missile bases on her land.”

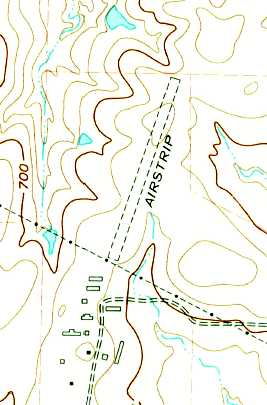

A single unpaved northeast/southwest runway was depicted at the site of Denton Field on the 1960 USGS topo map,

labeled simply as "Airstrip",

along with a number of buildings located to the southwest of the runway (possibly part of the Nike missile installation).

According to the book "Rings of Supersonic Steel" by Morgan & Berhow,

the Denton Nike base was turned over to the National Guard in 1964.

The Guard then continued to operate the base until it was closed in 1969.

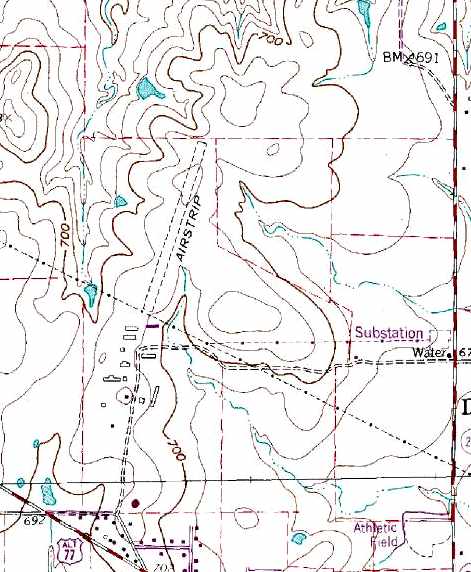

A single unpaved northeast/southwest runway was still depicted at the site of Denton Field on the 1978 USGS topo map,

labeled simply as "Airstrip",

along with a number of buildings located to the southwest of the runway (possibly part of the Nike missile installation).

Although not in use in the 1980s & early 1990s, Denton Field remained the property of the federal government.

The buildings of the former Nike control site were used for some period of time for storage by the Denton Board of Education,

before being abandoned.

A single northeast/southwest runway was still depicted at the site of Denton Field on the 1991 USGS topo map,

labeled simply as "Landing Strip".

Scott Murdock toured the remains of the former Denton Nike site in 1999,

which was by then privately owned.

Although numerous buildings remained at the site from its days as a Nike missile facility,

he did not note any remnants from its days as an airfield.

As seen in the 1995 USGS aerial photo,

the remains of the former Nike Control site at Denton were still quite intact (rectangular compound at upper-right).

However, no remnants of the former runway of Denton Field were still perceptible,

and the Loop 288 highway had been built through the southern portion of the site.

A 2005 photo by Chris Jackson, taken from “near the south end of the airstrip (just north of the airfield's buildings),

looking north/northeast in the general direction the airstrip followed.

In the distance you can see telephone poles that run along Highway Loop 288,

and a high spot in the topography that seems to be indicated on the topo map.”

Chris Jackson visited the site of College Field in 2005.

He reported: “The area immediately to the south of the airstrip (including all of the building indicated on the topo map)

is now a residential subdivision under construction.

The land which contained the actual airstrip is largely overgrown,

but is still undeveloped except where it is bisected by Highway Loop 288.”

A 2005 photo by Chris Jackson of an “artifact that I found on the airfield site.

The large text in the center reads 'New Daisy Pressure 50 Waterer',

and if you look at the bottom left corner you can see the date 1932.”

Was this artifact related to agriculture, or somehow related to the site's days as an airfield?

Kevin Raab reported in 2013, “Denton/College Field... I used to live a stone's throw away from there

and I never would have guessed that a little grass strip was once there.

As far as I can tell, no evidence remains whatsoever.”

The site of Denton Field is located north of the intersection of Loop 288 & North Locust Street,

3.5 miles north of the center of the town of Denton.

____________________________________________________

Hartlee Field (1F3, 3XS0), Denton, TX

33.268, -97.077 (North of Dallas Fort Worth Airport)

A 10/15/32 aerial view looking north at Hartlee Field

from the 1945 AAF Airfield Directory (courtesy of Scott Murdock).

The date of construction of Hartlee Field has not been determined,

but it evidently was not a pre-WW2 airfield,

as it was not listed among active airfields in The Airport Directory Company's 1937 Airport Directory (courtesy of Bob Rambo).

According to the Denton Record-Chronicle, George Harte contracted with the Army Air Force

and opened the Harte Flying Service here in about 1942.

It provided contractor flight training for military cadets,

and was also reported to have conducted glider training.

The earliest depiction of Hartlee Field which has been located was a 10/15/32 aerial view

from the 1945 AAF Airfield Directory (courtesy of Scott Murdock).

It depicted Hartlee as an open grass area with a single north/south runway

and several buildings along the west side.

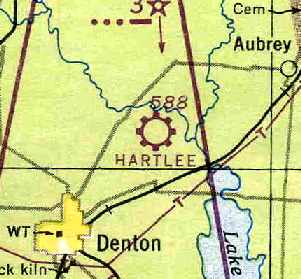

The earliest aeronautical chart epiction of Hartlee Field which has been located

was on the 1944 Dallas Sectional Chart (courtesy of David Brooks).

It depicted Hartlee as a commercial airfield.

A circa 1944 aerial view looking northeast at Hartlee Field (from the Portal to TX History, via Mike Shaw)

depicted the field as having a single north/south grass runway,

with 2 arch-roof hangars on the northwest side,

and dozens of aircraft.

According to the Portal to TX History, Hartlee Field was used to train officers

of the 1st Liason Training Detachment to fly Piper Cubs to aid in spotting artillery fire.

It also said that a glider school was taught at Hartlee Field,

and the headquarters of the school was located at Chilton Hall of North Texas State Technical College in Denton, TX.

The April 1944 U.S. Army/Navy Directory of Airfields (courtesy of Ken Mercer)

described Hartlee Field as having a 1,500' unpaved runway,

and indicated that Army flight operations were conducted from the field.

The 1945 AAF Airfield Directory (courtesy of Scott Murdock) described Hartlee Field

as a 250 acre irregularly-shaped property within which was a 2,650' gravel north/south runway & a 4,100' x 2,500' sod all-way landing area.

The field was said to have 4 steel hangars, with the largest being a 144' x 104' structure.

Hartlee Field was described as being privately owned & operated.

The March 1947 Dallas Sectional Chart (courtesy of Chris Kennedy)

depicted Hartlee as a commercial airfield.

An undated photo of 2 hangars labeled Hartlee Field (courtesy of Micheal McMurtrey).

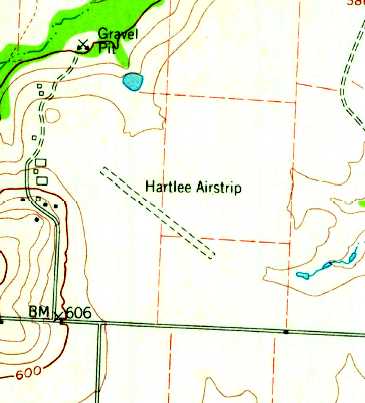

Strangely the 1960 USGS topo map depicted “Hartlee Airstrip” as having a single unpaved northwest/southeast runway,

whereas every other depiction shows a north/south runway orientation.

The 1963 TX Airport Directory (courtesy of Steve Cruse) described Hartlee Field as having a 2,600' sod runway.

The operator was listed as Harte Flying Service, and the manager was listed as George Harte.

Don Tedrow recalled, "I got my Private Pilot's certificate there in March 1974.

A Mr. George Vose ran the flight school there & gave my checkride.

My father, Dick Tedrow actually had the lease on the airport in the early 1980s, though I forget the exact dates.

I recall seeing an old photo that showed when Mr. Harte operated his flight school contract with the AAF during WW2,

there was a longer northwest/southeast turf runway,

the 'shadow' of which can be made out on the 1995 USGS photo (the dark band from upper left to lower right)."

According to Mark Nelson (who grew up near Hartlee Field in the late 1970's to early 1980's),

"I took my first light airplane ride there with my dad in 1978 or 1979."

pictured inside the WW2-era hangar at Hartlee Field.

As of at least the early 1980s, a group called the Fighting Air Command

operated a flyable collection of WW2 aircraft at Hartlee Field.

In the early 1980s, a group of WW1 replica airplanes

(which had been used in the filming of the movie "The Blue Max" in Ireland)

were purchased by FAC & shipped to Hartlee Field.

There, many of the planes were reassembled & flown by members.

The FAC Blue Max aircraft included: a Stampe SV-4c, three Fokker D.VII/65's,

two Pfalz D.III's, a Caudron 277, and four Slingsby Type 56's.

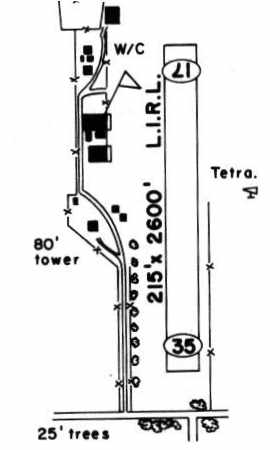

In the 1982 AOPA Airport Directory (courtesy of Ed Drury),

Hartlee was described as having a single 2,400' turf Runway 17/35.

The 1985 TX Airport Directory (courtesy of Steve Cruse) depicted a set of hangars just west of the runway,

and listed the manager as Scott Severen.

An undated photo of 8 yellow Piper Cubs lined up at Hartlee Field (courtesy of Micheal McMurtrey).

The FAC was disbanded in the late 1980s

and their collection of WW1 & WW2 aircraft was sold to various new owners.

According to Don Smith, "Interestingly, Hartlee Field was the primary airport

used for the filming of a move entitled 'Pancho Barnes' [a made-for-TV movie released in 1988].

The hangar markings don't say Hartlee Field.

They were changed to reflect 2 Nevada airports out of which she flew,

but the filming was done here, and anyone familiar with Hartlee

easily recognizes the Hartlee photos & movie scenes, including one in which they flew through a hangar.

For that scene they constructed a false hangar in the middle of the runway

and them removed it to restore the airport to operational condition."

The Hartlee Field Blue Max collection was described

in an article in the 3/88 issue of "Air Progress Warbirds" magazine.

The article author noted that "Most did not fly very well, especially in the hot Texas summers."

Hartlee Field was used for filming the video for Meat Loaf's 1993 video “Objects in the mirror are closer than they appear”,

which featured flying scenes of vintage biplanes & several shots of the hangar with “Hartlee Field” prominently visible.

Hartlee Field was still depicted as a private airfields on the January 1995 DFW Terminal Area Chart,

with a 2,200' unpaved runway.

In the 1995 USGS aerial photo of Hartlee,

what looked like the distinct outline of a paved runway & parallel taxiway with multiple turnoffs was actually an illusion.

According to Don Smith, "The clear markings of runway, taxiway, and turnoffs are not paved.

The grass grows up about knee to leg-high if it is not regularly mowed.

The ultralight group who were operating out of the field at that time groomed the field

for the Hartlee Pilots Reunion meeting that year & got very fancy with the mowing.

I thought it very clever of them to make all the turnoffs & a taxiway.

It made the field look like something it never was,

paved & marked with the regular trappings of a normal paved airport.

So, the photo depicts a neat job of mowing, not paving as it certainly appears."

Hartlee Field was apparently closed at some point between 1993-97,

as it had been dropped from the FAA records by 1997.

Lisa Simonds recalled "I took my private checkride at Hartlee

and a few years back used the field again to practice my wheels landings.

It was still in great shape in 1997."

A 1998 photo by Scott Murdock of the sign at the gate of "Historic Hartlee Field".

However, Scott reported, “A passerby told me the property had changed hands a year or 2 ago

and was no longer used as an airport."

Aerial view circa 2001.

This airfield has apparently been brought back to life,

because as of 2003, Hartlee Field was once again listed as an active private airfield.

It is described as having a single 2,200' turf Runway 17/35.

The owner is listed as Robert Payne, and the manager is listed as Mike Clark.

A total of 27 aircraft are listed as being based on the field,

and the field conducts an average of 134 takeoffs or landings per week.

According to Mark Nelson, "There is now a "Hartlee Field Reunion" held every Fall.”

Don Smith reported in 2003, "The property is now owned by Don Carter, former owner of the Dallas Mavericks.

It is operated as a privately owned, privately accessible airport, very limited access in fact.

I don't know if he allows anyone to land there except with his personal permission.

The major exception, still by his personal permission, is the Hartlee Pilot reunions each fall.

We usually have upwards of a couple of dozen planes there, with numerous flights all day long.

Last October we had half a dozen Cubs & many other makes & models, including a twin engine Aero Commander."

A November 2004 photo by Scott Murdock looking north along Hartlee Field's runway.

Scott reported that the sign previously marking the "historic airfield" was gone.

"From the public road, we could see a wind tetrahedron on the field,

and one or both hangars were visible through some trees."

A November 2004 photo by Scott Murdock looking north at Hartlee Field's hangars.

Stephen Bean reported in 2005, “This airfield is still owned by Don Carter.

Planes & helicopters take off from here on an almost daily occurrence.

Don Carter's son recently built a house about a quarter of a mile from the airfield & oversees the property

but Don Carter still owns & flies in & out as well as a few other guests.

I have been in the hangars & they are full of aircraft.”

A circa 2006 aerial view looking west at the 2 WW2-era hangars at Hartlee Field.

A 2013 photo by Kevin Raab looking northwest along the former Hartlee Field runway.

Kevin reported, “It appears the land is no longer used as an airfield.

The runway visible in the 2004 photo has all but disappeared.

It appears that some of the old hangars & buildings are still standing off in the distance, but I saw animals grazing down by the far end of the field instead of airplanes taxiing.”

A 2013 photo by Kevin Raab of the gate to the Hartlee Field property.

Kevin reported, The [airfield] sign at the entrance gate has disappeared.

The sign on the gate said the land owner is a member of a cattle raiser's association.

The only indication remaining that the property was once an airfield is the name of the road it's on, unfortunately.”

Hartlee Field is located north of the intersection of Hartlee Field Road & Cooper Creek Road,

4 miles northeast of the center of the town of Denton.

____________________________________________________

Bell Helicopter Auxiliary Heliport (6TA8), Hurst, TX

32.798, -97.15 (Southwest of Dallas Fort Worth Airport)

A 1990 aerial photo depicted the Hurst Training Heliport as having a single paved runway on the west side of the property.

A training complex of runways & helipads was evidently established by the Bell Helicopter Company

at this site at some point between 1981-90,

as it was not yet depicted at all on a 1979 aerial view nor on the 1981 USGS topo map.

The earliest depiction of this airfield which has been located was a 1990 aerial view.

It depicted the Hurst Training Heliport as having a single paved runway on the west side of the property.

The Bell Helicopter factory is located only a half-mile to the northwest.

The 1995 USGS aerial photo showed that 3 helipads had been added at some point between 1990-95 just east of the runway.

A second very short paved runway was added on the east side of the heliport at some point between 1995-2001,

as it was depicted on the 2001 USGS aerial photo.

Closed-runway “X” symbols had also been painted on the western runway,

but that may have been to discourage uninvited landings at this private facility,

rather than to indicate its closure.

A circa 2006 aerial view looking north at the southern end of the western runway.

Although the “Bell Helicopter Auxiliary Heliport” was still listed

with the FAA Airport/Facility Directory as of 2007 as a private heliport,

it was no longer depicted on aeronautical charts.

It was described as having a single 2,200' asphalt Helipad H1,

and the manager was listed as D.R. Lang.

The use of this training facility in Hurst may have been discontinued

due to the opening of the new Bell Training Academy at the Alliance Airport.

The Hurst Training Heliport is located southwest of the intersection of Trinity Boulevard & Greenbelt Road.

____________________________________________________

Since this site was first put on the web in 1999, its popularity has grown tremendously.

That has caused it to often exceed bandwidth limitations

set by the company which I pay to host it on the web.

If the total quantity of material on this site is to continue to grow,

it will require ever-increasing funding to pay its expenses.

Therefore, I request financial contributions from site visitors,

to help defray the increasing costs of the site

and ensure that it continues to be available & to grow.

What would you pay for a good aviation magazine, or a good aviation book?

Please consider a donation of an equivalent amount, at the least.

This site is not supported by commercial advertising –

it is purely supported by donations.

If you enjoy the site, and would like to make a financial contribution,

you

may use a credit card via