Cantorian Fractal Space-Time

Fluctuations in Turbulent Fluid Flows and Kinetic Theory of Gases

A. M. Selvam

Deputy Director (Retired)

Indian Institute of Tropical

Meteorology, Pune 411 008, India

Fluid flows such as gases

or liquids exhibit space-time fluctuations on all scales extending down

to molecular scales. Such broadband continuum fluctuations characterise

all dynamical systems in nature and are identified as selfsimilar fractals

in the newly emerging multidisciplinary science of nonlinear dynamics

and chaos. A cell dynamical system model has been developed by the

author to quantify the fractal space-time fluctuations of atmospheric

flows. The earth's atmosphere consists of a mixture of gases and obeys

the gas laws as formulated in the kinetic theory of gases developed

on probabilistic assumptions in 1859 by the physicist James Clerk Maxwell.

An alternative theory using the concept of fractals and chaos

is applied in this paper to derive the fundamental equation of the kinetic

theory of ideal gases and the Maxwell’s distribution of molecular

speeds.

Keywords: fractals,

chaos, kinetic theory of gases, gas laws

1.Introduction

Kinetic theory of ideal

gases is a study of systems consisting of a great number of molecules,

which are considered as bodies having a small size and mass (Kikoin and

Kikoin, 1978). Classical statistical methods of investigation (Dennery,

1972; Yavorsky and Detlaf, 1975; Kikoin and Kikoin, 1978; Rosser, 1985;

Guenault, 1988; Gupta, 1990; Ruhla, 1992; Dorlas, 1999; Chandrasekhar,

2000) are employed to estimate average values of quantities characterizing

aggregate molecular motion such as mean velocity, mean energy etc., which

determine the macro-scale characteristics of gases. The mean properties

of ideal gases are calculated with the following assumptions. (1) The intra-molecular

forces are completely absent instead of being small. (2) The dimensions

of molecules are ignored, and considered as material points. (3) The above

assumptions imply the molecules are completely free, move rectilinearly

and uniformly as if no forces act on them. (4) The ceaseless chaotic movements

of individual molecules obey Newton’s laws of motion.

The observed nonlinear space-time fluctuations of microscopic objects such

as atoms and molecules in an ideal gas are now (since 1980s) identified

as fractals generic to macro-scale real world dynamical systems

in nature such as, fluid flows, stock market price fluctuations, heart

beat patterns etc. The apparently chaotic (nonlinear) fractal fluctuations

however exhibit self-similarity, i.e., long-range space-time correlations.

The identification of the physical laws governing fractal fluctuations

is an intensive field of research in the newly (since 1980s) emerging science

of Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos (Gleick, 1987). Mary Selvam (1990)

has developed a general systems theory for the simulation and prediction

of the observed fractal space-time fluctuations in dynamical systems

of all size scales ranging from the microscopic scale of atoms and molecules

to macro-scale turbulent fluid flows. The model concepts are applied to

derive the following classical relationships for an ideal gas: (1) pressure

exerted by an ideal gas (2) the Boltzmann distribution for molecular

energies (3) the Maxwell distribution of molecular velocities. The

derivation of the above relationships according to classical statistical

methods is briefly described followed by a detailed discussion of the fractal

concepts applied to derive the same equations.

The important new contributions of the general systems theory applied to

model ideal gases are as follows: (1) fractal fluctuations are signatures

of quantum-like chaos on all scales ranging from subatomic dynamics of

quantum systems to real world macro-scale fluid flows (2) quantum mechanical

laws are applicable to dynamical systems of all size scales.

The general systems theory concepts used in the derivation of the fundamental

equations for the kinetic theory of gases have been applied earlier by

the author for the simulation and prediction of both microscopic and macro-scale

dynamical systems (Selvam, 1990; Selvam, 1993; Selvam, and Fadnavis, 1998;

Selvam and Suvarna Fadnavis, 1999a; Selvam, and Suvarna Fadnavis, 1999b;

Selvam, 2001).

In the following, Sections 2, 3 and 4 deal respectively with application

of the model concepts to derive the following three classical relationships

for an ideal gas: (1) pressure exerted by an ideal gas (2) the Boltzmann

distribution for molecular energies (3) the Maxwell distribution

of molecular velocities. The derivation of the above relationships according

to classical statistical methods is briefly described followed by a detailed

discussion of the fractal concepts applied to derive the same equations.

In conclusion Section 5 discusses the universal characteristics of fractal

space-time fluctuations, a signature of quantum-like chaos exhibited by

dynamical systems of all size scales ranging from sub-atomic dynamics of

quantum systems to macro-scale turbulent fluid flows. The model shows that

quantum mechanical laws are applicable to macro-scale real world dynamical

systems and also provides physically consistent interpretations for wave-particle

duality and non-local connection exhibited by microscopic-scale quantum

systems which so far do not have a satisfactory explanation on the basis

of current concepts in quantum mechanics.

2. Pressure exerted by

an ideal gas

2.1 Classical statistical

physics

A brief summary of the

method for calculating pressure based on classical statistical physics

concepts is given in the following The molecular collisions exert a force

on the walls of the vessel containing the gas and this force is measured

by the parameter pressure, which is equal to the force per unit

area perpendicular to the direction of the force.

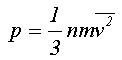

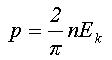

The pressure

p is calculated as

where n is the

number of molecules per unit volume, m is the mass of one molecule

and

where n is the

number of molecules per unit volume, m is the mass of one molecule

and  represents the mean square velocity in any one direction

x, y

or z. The pressure p may be written as

represents the mean square velocity in any one direction

x, y

or z. The pressure p may be written as

(1)

In Equation (1) Ek

is equal to the mean kinetic energy  of one molecule of a gas. Consequently the pressure of a gas equals two-thirds

of the mean kinetic energy of the molecules contained in a unit of its

volume. This is one of the most important conclusions of the kinetic theory

of an ideal gas. Equation (1) establishes a relationship between molecular

quantities, i.e., quantities relating to a separate molecule, and the value

of the pressure characterizing a gas as a whole – a macroscopic quantity

directly measured in experiments. Equation (1) is sometimes called the

fundamental

equation of the kinetic theory of ideal gases.

of one molecule of a gas. Consequently the pressure of a gas equals two-thirds

of the mean kinetic energy of the molecules contained in a unit of its

volume. This is one of the most important conclusions of the kinetic theory

of an ideal gas. Equation (1) establishes a relationship between molecular

quantities, i.e., quantities relating to a separate molecule, and the value

of the pressure characterizing a gas as a whole – a macroscopic quantity

directly measured in experiments. Equation (1) is sometimes called the

fundamental

equation of the kinetic theory of ideal gases.

2.2 General systems theory

One of the most convincing

demonstrations that gases really are made up of fast moving molecules is

Brownian

motion, the observed constant jiggling around of tiny particles, such as

fragments of ash in smoke. This motion was first noticed in 1827 by the

British botanist, Robert Brown who initially assumed he was looking at

living creatures, but then found the same motion in what he knew to be

particles of inorganic material. Einstein showed how to use Brownian motion

to estimate the size of atoms (Kikoin and Kikoin, 1978; Fowler, 1997; Lee

and Kelvin).

Chaotic fluctuations such as those executed by molecules in a gas are now

identified as fractals generic to space-time fluctuations of dynamical

systems in nature (Mandelbrot, 1977; 1983; Gaspard et al., 1998).

Identification of the physics of fractal fluctuations and quantification

is an intensive field of research in the newly emerging (since 1980s) multidisciplinary

science of Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos (Gleick, 1987). It has been

long supposed that the existence of chaotic behaviour in the microscopic

motions of atoms and molecules in fluids or solids is responsible for their

equilibrium and non-equilibrium properties. Recently this hypothesis of

microscopic chaos has been verified experimentally by Gaspard et al.

(1998) who found evidence for microscopic chaos in fluid systems, by the

observation of Brownian motion of a colloidal particle suspended in water.

Mary Selvam (1990) has developed a general systems theory (Capra, 1996)

for the observed space-time fractal fluctuations in dynamical systems,

which enable quantification of large-scale fluctuations in terms of inherent

smaller scale fluctuation characteristics. The irregular fractal

fluctuations occur on all space-time scales and may be considered to result

from the superimposition of a continuum of eddies or waves such as sine

waves. An eddy is basically a circular motion characterized by the radius

r

and r.m.s (root mean square) circulation speed w*.

Larger scale fluctuations result from the integration of enclosed smaller

scale fluctuations. The relationship between the r.m.s circulation speeds

W

and w*

of large and small eddy of respective radii R and r is given

as (Townsend, 1956; Mary Selvam, 1990)

(2)

The above equation represents

the growth of an eddy continuum with formation of a hierarchy of successively

larger eddies from enclosed smaller scale eddies. The square of the eddy

amplitude, i.e., W2

represents the eddy energy (kinetic). The large eddy energy is the integrated

mean of the enclosed smaller scale eddy energies and therefore the eddy

energy spectrum will follow statistical normal distribution according to

the Central Limit Theorem (Ruhla, 1992). Such a result that the

additive amplitudes (W) of eddies, when squared (W2)

represent the statistical normal distribution is exhibited by subatomic

dynamics of quantum systems such as the electron or photon (Maddox, 1998;

1993).

By analogy with quantum mechanics the square of the eddy amplitude W2

represents the kinetic energy E given as (from Equation 2)

In the above Equation

the parameter n

(proportional to 1/R) is the frequency of the large eddy and H

is a constant equal to

In the above Equation

the parameter n

(proportional to 1/R) is the frequency of the large eddy and H

is a constant equal to  for the growth of large eddies sustained by constant energy input proportional

to w*2

from fixed primary small scale eddy fluctuations. Energy content of eddies

is therefore similar to quantum systems which can possess only discrete

quanta or packets of energy content hn

where h is a universal constant of nature (Planck's constant) and

n

is the frequency in cycles per second of the electromagnetic radiation.

for the growth of large eddies sustained by constant energy input proportional

to w*2

from fixed primary small scale eddy fluctuations. Energy content of eddies

is therefore similar to quantum systems which can possess only discrete

quanta or packets of energy content hn

where h is a universal constant of nature (Planck's constant) and

n

is the frequency in cycles per second of the electromagnetic radiation.

The macro-scale eddy continuum represented by Equation (2) obeys quantum-like

mechanical laws, a manifestation of quantum-like chaos. The apparent paradox

of wave-particle duality exhibited by microscopic scale quantum systems

such as an electron or photon is however physically consistent in the context

of real world macro-scale dynamical systems as explained in the following.

The bi-directional energy flow intrinsic to eddy circulations is associated

with bimodal, i.e., formation and dissipation respectively of phenomenological

form for manifestation of energy such as the formation of clouds in updrafts

and dissipation of clouds in adjacent downdrafts resulting in the observed

discrete cellular geometry to cloud structure. The commonplace occurrence

of clouds in a row is a manifestation of wave-particle duality in macro-scale

atmospheric flows. By analogy, the molecules (atoms) of an ideal gas may

be visualised as the manifestation of matter during a half-cycle of an

eddy circulation (Mary Selvam, 1990; Selvam and Fadnavis, 1999a). The primary

perturbation of r.m.s circulation speed w*

and eddy radius r represents the wave-like structure of a molecule

or atom in the ideal gas, the manifestation of matter of molecular mass

m

occurring during half a cycle of the complete circulation as explained

above.

The length scale ratio

R/r

in the above Equation (2) represents the fractional volume intermittency

of occurrence of small-scale (fractal) structures (Mary Selvam,

1993) across unit area of large eddy surface as shown in the following.

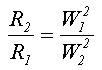

Considering two large

eddy circulations of respective radii R1

and R2

(R2 being

greater than R1)

and corresponding r.m.s circulation speeds W1

and W2

which grow from the same small-scale primary perturbation of radius r

and r.m.s circulation speed w*,

we have from Equation (2)

(3)

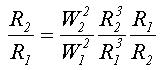

Introducing the factor  representing eddy volumes on both sides of the above equation we have

representing eddy volumes on both sides of the above equation we have

(4)

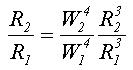

Therefore

(5)

Substituting for R1/

R2 on the right

hand side from Equation (3) we have the following relation for fractional

volume intermittency of occurrence of small-scale fluctuations given by

the fourth moment about the mean for the relative eddy transports as

(6)

The length scale ratio

R1/

R2 is equal to

the transport of fractional volume of small-scale fluctuations in the environment

of the large eddy (per unit volume of large eddy), basically by eddy mixing

process. Considering large and small eddies of respective radii R

and r and r.m.s circulation speeds W and w*

the corresponding mass transport M of gas across unit area for half

cycle of large eddy circulation in terms of molecular mass is equal to  . The molecular mass m corresponds to the small-scale primary eddy

perturbation. Multiplying both sides of Equation (2) by nm/2 and

rewriting

. The molecular mass m corresponds to the small-scale primary eddy

perturbation. Multiplying both sides of Equation (2) by nm/2 and

rewriting

(7)

In

the above equation the large eddy circulation speed W represents

the acceleration since it is computed as an incremental value relative

to its earlier stage of eddy growth. The pressure p exerted by the

gas is given by the product MW equal to the rate of change of momentum

due to molecular impact across unit area of the large eddy surface. Equation

(7) may now be written as

(8)

The r.m.s eddy circulation

speed w* represents

by concept the average molecular speed in any direction and the average

kinetic energy of one molecule designated by Ek

is equal to  . The above Equation (8) may now be written as

. The above Equation (8) may now be written as

(9)

Equation (9) is almost

the same as Equation (1), the fundamental equation of the kinetic theory

of ideal gases, namely,  .

.

The important differences

in the physical concepts underlying the derivation of the fundamental

equation of the kinetic theory of ideal gases by classical statistical

physical methods and the general systems theory for fractal space-time

fluctuations are as follows: (1) The general systems theory visualises

molecules or atoms as manifestation of matter during half a cycle of eddy

circulation. Classical physics visualises molecules and atoms as point

objects. (2) The r.m.s velocity w*

represents the average velocity for computation of mean molecular kinetic

energy in the general systems theory. The mean square velocity of the molecule

or atom in any one direction (x, y or z) equal to  is used for computing the molecular kinetic energy in classical physics.

is used for computing the molecular kinetic energy in classical physics.

3. Boltzmann distribution

for molecular energies in an ideal gas

3.1 Classical physics

For any system large or

small in thermal equilibrium at temperature T, the probability P

of being in a particular state at energy E is proportional to  where kB is the Boltzmann’s

constant. This is called the Boltzmann distribution and may be written

as

where kB is the Boltzmann’s

constant. This is called the Boltzmann distribution and may be written

as

(10)

3.2 General systems theory

The physical concepts

of the general systems theory enables to show that precise ordered mathematical

patterns underlie the apparently chaotic space-time fluctuations of dynamical

systems. The irregular fractal fluctuations of dynamical systems

may be visualized to result from the superimposition of an ensemble of

eddies, namely an eddy continuum. An eddy continuum by concept consists

of a hierarchy of eddies, the larger scale eddies enclosing smaller scale

eddies. The larger scale eddies grow by the spatial integration of enclosed

smaller scale eddies and the growth trajectory traces an overall logarithmic

spiral flow path with the quasiperiodic Penrose tiling pattern for

the internal structure (Mary Selvam, 1990; Selvam and Fadnavis, 1998).

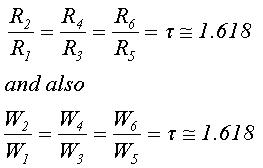

The ratio of radii (R2/

R1) or r.m.s.

circulation speeds (W2/W1)

corresponding to the successive growth steps of the large eddy generating

the geometry of the quasiperiodic Penrose tiling pattern is equal

to the golden mean t

(@

1.618).

(11)

The r.m.s circulation

speed W of the large eddy follows a logarithmic relationship with

respect to the length scale ratio z equal to R/r as given

below

(12)

In Equation (12) the variable

k

represents for each step of eddy growth, the fractional volume dilution

of large eddy by turbulent eddy fluctuations carried on the large eddy

envelope and is given as

(13)

Incidentally, Equation

(12) represents the observed logarithmic spiral air flow structure in the

planetary atmospheric boundary layer and the constant k called the

von

Karman’s constant is determined from observations to be equal to about

0.38

(Mary Selvam, 1990; Selvam and Fadnavis, 1998).

From Equations (11)

and (13) it is seen that, for successive large eddy growth steps generating

the quasiperiodic Penrose tiling pattern, the value of k

is equal to 1/t2

(@0.38)

where t

is the golden mean (@1.618).

Substituting for k in Equation (12) we have

(14)

Therefore

(15)

The ratio r/R represents

the fractional probability P of occurrence of small-scale fluctuations

(r) in the large eddy (R) environment. Considering two large

eddies of radii R1

and R2

(R2

greater than R1)

and corresponding r.m.s circulation speeds W1

and W2

which grow from the same primary small-scale eddy of radius r and

r.m.s circulation speed w*

we have from Equation (2)

(16)

From Equations (15) and

(16)

(17)

The square of r.m.s circulation

speed W2

represents eddy kinetic energy. Following classical physical concepts (Kikoin

and Kikoin, 1978) the primary (small-scale) eddy energy may be written

in terms of the eddy environment temperature T and the Boltzmann’s

constant kB as

(18)

Representing the larger

scale eddy energy as E

(19)

The length scale ratio

R1/R2

therefore represents fractional probability P of occurrence of large

eddy energy E in the environment of the primary small-scale eddy

energy kBT

(Equation 18). The expression for P is obtained from Equation (17)

as

(20)

The above Equation (20)

is the same as the Boltzmann’s equation (Equation 10).

The derivation of

Boltzmann’s

equation from general systems theory concepts visualises the eddy energy

distribution as follows: (1) The primary small-scale eddy represents the

molecules whose eddy kinetic energy is equal to kBT

as in classical physics. (2) The energy pumping from the primary small-scale

eddy generates growth of progressive larger eddies (Mary Selvam, 1990).

The r.m.s circulation speeds W of larger eddies are smaller than

that of the primary small-scale eddy (Equation 2). (3) The space-time fractal

fluctuations of molecules (atoms) in an ideal gas may be visualised to

result from an eddy continuum with the eddy energy E per unit volume

relative to primary molecular kinetic energy (kBT)

decreasing progressively with increase in eddy size.

4. Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution

of molecular speeds

4.1 classical physics

The distribution of molecular

speeds was derived by Maxwell based on the probabilistic assumptions,

namely (i) uniform distribution in space, (ii) mutual independence of the

three velocity components and (iii) isotropy as regards the directions

of the velocities (Ruhla, 1992). These assumptions were also used in deriving

the fundamental gas law at Equation (1) for a perfect gas. Maxwell's

distribution of molecular speeds is given by the following equation.

(21)

where r(v)

is the probability density assigned to the speed v, T is

the absolute temperature of the perfect gas, m is the mass of a

molecule and kB

is the Boltzmann's constant. For a given gas at a fixed temperature

T,

the probability density r(v)

may be written as

(22)

A graph of Maxwell's

distribution of molecular speeds is shown in Figure 1.

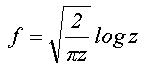

4.2 General systems theory

The steady state upward

transport of small-scale fluctuation of speed w*

and size scale r in the environment of larger scale fluctuation

of speed W and size R is given as (Mary Selvam, 1990; Selvam

and Fadnavis, 1998)

(23)

In Equation (23) z

is the length scale ratio equal to R/r. Considering three-dimensional

fluctuations the fractional contribution (probability density) of smaller

length scale r fluctuations in the environment of the larger length

scale R fluctuation is given by f 3.

The eddy circulation speeds follow the logarithmic law with respect to

the length scale ratio z (Equation 12), namely

The eddy circulation speeds

are therefore proportional to log z, that is

The eddy circulation speeds

are therefore proportional to log z, that is

(24)

A graph of f 3

versus log z will give the probability density distribution for

molecular speeds. The cell dynamical system model predicted molecular speed

distribution in a perfect gas is shown as crosses in Figure 1. The distributions

(Maxwell's and model predicted) are normalized with respect to the

maximum speed. There is close agreement between the Maxwell's and

model-predicted distributions for molecular speeds in a perfect gas.

Figure 1

5. Conclusions

Dynamical systems of all

size scales ranging from microscopic scale quantum systems to macro-scale

turbulent fluid flows exhibit self-similar fractal space-time fluctuations.

Self-similarity implies long-range space-time correlations or non-local

connections such as that observed in quantum systems. A general systems

theory developed by the author enables to show quantitatively that the

observed fractal space-time fluctuations generic to dynamical systems

in nature are signatures of quantum-like chaos. The model concepts for

Cantorian

fractal space-time fluctuations is applied to derive the fundamental

gas law, namely  and also the Maxwell’s molecular speed distribution for a perfect

gas. The model predictions are in agreement with Maxwell's kinetic

theory of gases developed in 1859 on probabilistic assumptions.

and also the Maxwell’s molecular speed distribution for a perfect

gas. The model predictions are in agreement with Maxwell's kinetic

theory of gases developed in 1859 on probabilistic assumptions.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful

to Dr. A. S. R. Murty for his keen interest and encouragement during the

course of the study.

References

Bak, P., C. Tang, K. Wiesenfeld,

1987: Self-organized criticality: an explanation of 1/f noise. Phys.

Rev. Lett. 59, 381-384.

Bak, P., C. Tang, K. Wiesenfeld,

1988: Self-organized criticality. Phys. Rev. A. 38, 364-374.

Chandrasekhar, B. S.,

2000: Why are Things the Way They are, Cambridge University Press,

Cambridge, pp.251.

Capra, F., 1996: The

Web of Life, Harper Collins, London, pp. 311.

Dennery, P., 1972: An

Introduction to Statistical Mechanics, George Allen and Unwin Ltd.,

London, pp.116.

Dorlas, T. C., 1999: Statistical

Mechanics, Institute of Physics Publishing, Bristol, London, pp.267.

Fowler, M., 1997: Brownian

motion, http://www.phys.virginia.edu/classes/252

Gaspard, P., M. E. Briggs,

M. K. Francis, J. V. Sengers, R. W. Gammon, J. R. Dorfman and R. V. Calabrese,

1998: Experimental evidence for microscopic chaos, Nature 394,

865-867.

Gupta, M. C., 1990: Statistical

Thermodynamics, Wiley Eastern Ltd., New Delhi, pp.401.

Gleick, J., 1987: Chaos:

Making a New Science. Viking , New York.

Kikoin, A. K. and I. K.

Kikoin, 1978: Molecular Physics, Mir Publishers, Moscow, pp.471.

Lee, Y. K. and H. Kelvin,

---Brownian Motion-The Research Goes On http://www.doc.ic.ac.uk/~nd/surprise_95/journal/vol4/ykl/report.html

Maddox, J., 1988: Licence

to slang Copenhagen? Nature 332, 581.

Maddox, J., 1993: Can

quantum theory be understood? Nature 361, 493.

Mandelbrot, B.B., 1977:

Fractals:

Form, Chance and Dimension, Freeman, San Francisco.

Mandelbrot, B.B., 1983:

The

Fractal Geometry of Nature, W.H. Freeman, pp.468.

Newman, M., 2000: The

power of design, Nature 405, 412-413.

Rosser, W. G., 1985: An

Introduction to Statistical Physics, Ellis Horwood Publishers, Chichester,

West Sussex, England, pp. 377.

Ruhla, C., 1992: The

Physics of Chance, Oxford university press, pp. 217.

Selvam, A. M., 1990: Deterministic

chaos, fractals and quantum-like mechanics in atmospheric flows, Canadian

J. Physics 68, 831-841. http://xxx.lanl.gov/html/physics/0010046

Selvam, A. M., 1993: Universal

quantification for deterministic chaos in dynamical systems, Applied

Mathematical Modelling 17, 642-649. http://xxx.lanl.gov/html/physics/0008010

Selvam, A. M. and S. Fadnavis,

1998: Signatures of a universal spectrum for atmospheric interannual variability

in some disparate climatic regimes, Meteorology and Atmospheric Physics

66, 87-112, (Springer-Verlag, Austria) http://xxx.lanl.gov/abs/chao-dyn/9805028.

Selvam, A. M. and Suvarna

Fadnavis, 1999a: Superstrings, Cantorian-fractal space-time and quantum-like

chaos in atmospheric flows, Chaos, Solitons and Fractals 10(8),

1321-1334. http://xxx.lanl.gov/abs/chao-dyn/9806002.

Selvam, A. M., and Suvarna

Fadnavis, 1999b: Cantorian fractal spacetime, quantum-like chaos and scale

relativity in atmospheric flows, Chaos, Solitons and Fractals 10(9),

1577-1582. http://xxx.lanl.gov/abs/chao-dyn/9808015.

Selvam, A. M., 2001: Quantum-like

chaos in prime number distribution and in turbulent fluid flows. http://xxx.lanl.gov/html/physics/0005067

Published with modification in the Canadian electronic journal APEIRON

8(3), 29-64, (2001). http://redshift.vif.com/JournalFiles/V08NO3PDF/V08N3SEL.PDF

Yavorsky, B. and A. Detlaf,

1975: Handbook of Physics, Mir Publishers, Moscow, pp.965.