In a time when even middle infielders are expected to hit for power and average, is there any way for a player of modest offensive skills to have a lengthy big league career?

Just look behind the plate to find the answer. Catchers who work well with pitching staffs and play solid defense often spend a decade or more in the majors regardless of their batting average.

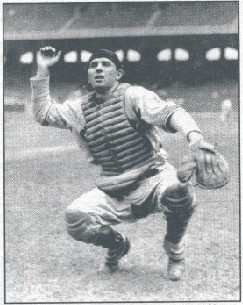

This is hardly a new trend, as the story of Bill Bergen demonstrates the value of a skilled receiver. Despite an all-time low .170 career batting average, Bergen was a regular or platoon catcher for the Reds and Dodgers from 1901 to 1911. He accumulated 3,028 at-bats while having just one season above .200. Bergen slammed just two home runs during his dead-ball career, and he failed to hit above .175 from 1906 to 1911.

A .212 lifetime average wasn't enough to keep Billy Sullivan from catching in the majors for 14 seasons. Fellow dead-ball receiver Lou Criger regularly caught Cy Young despite a .221 career mark, and it wasn't uncommon for other regular catchers to hit under .200 over the course of a season.

When stolen bases and bunt singles were an important part of offensive strategy, a catcher's defensive skills were more important than his bat. After the introduction of the live ball in 1920, the good-field, weak-hitting catcher was far less common.

The breed made something of a comeback from 1942 to 1945, when hundreds of major leaguers were drafted into the U.S. armed forces. With the reduction in offense and a general shortage of talent, weak-hitting catchers who could handle pitchers and play defense were able to find work with a number of teams.

Those who demand proof that a catcher's offensive statistics can play a secondary role to what he does behind the plate should examine Jim Hegan's career.

|

No one else with a .228 lifetime average has been named to five All-Star teams, and this took place in a time before expansion. Yogi Berra and Roy Campanella may have been the hardest-hitting backstops of the late '40s and early '50s, but Hegan was tops defensively when it came time to don shin guards and a chest protector.

As the Indians starting catcher for a decade, Hegan played a vital role on two of the franchise's three pennant winners in its first 90 years of existence - and it wasn't a matter of luck or coincidence.

Just ask Hall of Famer Bob Feller about Hegan's importance to the Cleveland pennant winners, and he'll repeatedly compliment his old catcher and proclaim that Hegan was one of the Tribe's most valuable starters. That's high praise for a man who never hit above .249 over a full season.

|

|

Hegan was one of those rare players who picked up rave reviews for his glove from teammates and opponents alike. Bill Dickey was quoted as saying, "When you can catch like Hegan, you don't have to hit."

With his knowledge of catching, Hegan never lacked for a job as a major league coach after he retired as a player. When the best defensive catchers of all time are the topic of conversation, Hegan is still one of the most popular choices more than 40 years after his final game.

Wes Westrum was another postwar catcher who played regularly for contending teams. He spent a decade (1947-57) with the New York Giants, despite a .217 lifetime average. In addition to his glove and pitch-calling skills, Westrum also hit for power, with two 20-home run seasons to his credit. Although his batting average was near the bottom of the league, Westrum was a patient hitter who had nearly as many career walks (489) as hits (503).

Bob "Buck" Rodgers wasn't a big run producer, but he was usually behind the plate for the Los Angeles/California Angels from 1962 to 1969. From 1965 to 1967, Rodgers appeared in more than 130 games each season (a huge total for a catcher) while batting .209, .236 and .219. He later managed the Brewers, Expos and Angels.

The need for quick catchers with good arms grew as base stealing made a comeback in the late 1950s and early 1960s. While weak bats may have prevented some defensive aces from starting roles, they often enjoyed long careers as backup or platoon catchers.

Mike Ryan's batting average never strayed very far above the .200 level in his decade-long time in the majors. His .193 lifetime mark is one of the lowest in baseball history. Despite that, Ryan played for the Red Sox, Phillies and Pirates from 1964 to 1974. Like many other catchers, he remained in uniform as a coach after his career ended.

Phil Roof played for eight teams from 1961 to 1977. His .215 lifetime average wasn't high enough for a starting job, but Roof's career was far longer than average.

Marlins' manager Jeff Torborg caught no-hitters for Sandy Koufax and Nolan Ryan. The beating his hands took from those fireballers may have contributed to Torborg's .214 career average.

Bob Uecker has relied on his unique sense of humor to sustain a 32-year career as a baseball announcer and TV personality. Often the butt of his own jokes, one of Uecker's favorite topics is his .200 lifetime average as a catcher with the Braves, Cardinals and Phillies. What Uecker leaves out in his stories are the defensive skills that allowed him to play in the majors. His contemporaries say that Uecker was solid behind the plate - good enough to catch Phil Niekro in 1967 when the knuckleballer led the National League with a 1.87 ERA. That's nothing to joke about, even for "Mr. Baseball."

Dave Duncan caught 113 games for the world champion Oakland A's in 1972. His 19 HRs and 59 RBI were career highs, but his .218 average mirrored Duncan's .214 lifetime mark. Widely respected for his catching skills and knowledge of the game, Duncan is the long-time Cardinals pitching coach.

|

He was never considered a major threat at the plate, but Rick Dempsey is regarded as one of the better defensive catchers of the 1970s and 1980s. Always know for his intensity, Dempsey played in the majors for 24 consecutive seasons (1969-92). He spent the first third of his career as a reserve, and a 1976 trade from the Yankees to the Orioles proved to be a turning point.

The right-handed hitting Dempsey immediately became Baltimore's starting catcher and held the job for a decade. He was the Most Valuable Player of the 1983 World Series, hitting an unexpected .385. All five of Dempsey's Series hits - four doubles and a homer - went for extra bases.

A 38-year old with a .177 average for a last-place team (the '87 Indians) usually needs to find another career, but Dempsey still had more than four seasons of baseball to play. He signed with the Dodgers and ended up in his third World Series. Dempsey returned to the Orioles for eight games in 1992, closing out his nearly quarter-century big league run with a .233 lifetime average.

|

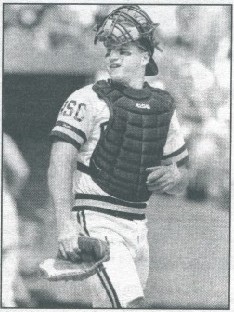

Ron Karkovice spent a dozen seasons (1986-1997) behind the plate for the White Sox. His reputation as a solid defensive catcher who could throw out base stealers allowed Karkovice to be a regular player despite a .221 career batting average.

Twins backup catcher Tom Prince has been in the majors since 1987. With his .209 career average (through August 15, 2002), it's obvious that Prince's defensive and pitch-calling skills have kept him in the majors until the ripe old age of 38. "It's the physical beating that cuts into a catcher's hitting," Prince observed. "I don't make excuses, but catchers take foul balls off their knees, elbows and every other part of the body. Most guys will lose 20 to 30 points off their average by catching."

|

Prince has never appeared in more than 66 games in any big league season. It's a case of being in the wrong place at the wrong time. "I've backed up a lot of star players," he said. "I was behind Mike Lavalliere in Pittsburgh, and he was a Gold Glover. Don Slaught was also there, and those two were the best righty-lefty hitting platoon catchers in the majors." Prince continued: "I backed up Mike Piazza with the Dodgers, and he's one of those elite few catchers who hits well every season. Then I went to the Phillies, and Mike Lieberthal is an All-Star. Now I back up A.J. Pierzynski. He handles pitchers well and hits, and he's an All-Star."

When Prince was signed by the Twins after the 2000 season, he was told to concentrate on his work behind the plate. "I talked with Tom Kelly, and he told me they were looking for a backup catcher who could work well with young pitchers," Prince said.

|

|

It appears that Prince has successfully performed the task he was signed for, if one considers the steady progress made by Minnesota's young pitchers. "I'm not taking any credit for how well the pitchers have done," he remarked. "Kyle Lohse and Johan Santana have stepped up and done a great job. They've got a bright future. It rejuvenates an old man like me."

Charlie O'Brien is an ultimate example of how a strong defensive catcher can always find work. It wasn't his .221 lifetime average and so-so power that kept O'Brien in the majors from 1985 to 2000. He blocked errant pitches in the dirt, expertly framed borderline tosses, turning them into strikes and worked masterfully with pitchers.

O'Brien was Greg Maddux's personal catcher in 1994 and 1995 when the Atlanta ace was winning two of his four consecutive N.L. Cy Young Awards.

It's no coincidence that Pat Hentgen went 20-10 and picked up an American League Cy Young when O'Brien moved on to the Toronto Blue Jays in 1996.

Henry Blanco may be the next O'Brien. Like his predecessor, Blanco is Maddux's personal catcher, and the Venezuela native is regarded as one of the best defensive receivers in the game. Hitting has been Blanco's biggest obstacle, as illustrated by a .227 lifetime average. Even though he gunned down half of all opposing base stealers, Blanco was deemed expendable by the Milwaukee Brewers after seasons of batting .236 and .210.

At 31, Blanco may have a long career ahead. Ironically, this defensive whiz didn't catch until 1995, his sixth year in the minors.

While a big bat is always an asset, a catcher's brain, arm and pitch-calling abilities are far more vital than a few extra hits over the course of a season. Do the job behind the plate, and it could lead to 10 or 15 years in the majors.

Copyright © 2002 by Baseball Digest.