|

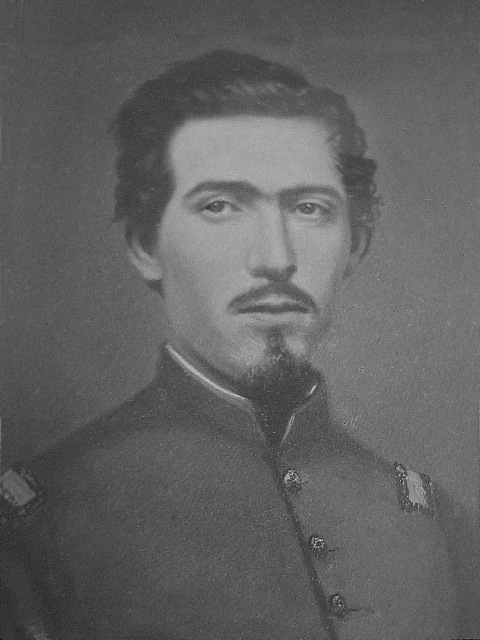

Second Lieutenant DAVID E. CANFIELD |

||

|

Second Lieutenant DAVID E. CANFIELD, was born in Newark, New Jersey, probably in the year 1839, as he was down on his company muster-roll as twenty-three years of age at enlistment, July 16, 1862. Of his early life I have gleaned a few incidents from an uncle in Middletown, Conn., of whom he learned his trade as a marble carver. It seems that as a lad he exhibited a rare taste for drawing, and once when quite a little fellow, made an equestrian drawing of Gen. Scott, during the visit of that old hero to Newark. Some days after, on some public occasion, his father presented the lad and the picture to the General, who inspected, commended, and wrote his autograph upon its back, and returned it to the father, who values it now as a doubly precious relic. At his trade his taste was so promisingly called into play that his master and fellow workmen feel very sure that he would have won eminence in his vocation. After five years labor in Middletown, he removed to New Haven, where the call for the 14th aroused his patriotism and rekindled an old fondness for military life, and he returned to Middletown to enlist under Lieut. Crosby, in Company K of the 14th. To a favorite cousin, in whose album he drew a picture of a delicate bouquet as a parting memorial of himself, he remarked that she might rest assured that he would win distinction or lose his life. Little did she think that within five months he would do both. Canfield was made 1st sergeant of his company ere it left the State, and Nov. 11, 1862, was promoted to be 2d Lieutenant of B Company, which was almost entirely composed of Middletown boys. During his brief connection with this company, he won their love and respect, as he had that of Company K before. The night of December 12, 1862, Lieut. Canfield, Capt. Gibbons, Capt. (then Lieut.) Sherman, and the writer, occupied the same quarters in a shot-ridden house in the then just captured city of Fredericksburg. Never shall I forget the scene as Capt. Gibbons read to us from an old Bible found in the house, till the flickering fire-light by which he read died out, and bidding us each good-night, with a reminder that it might be our last good-night, he retired. Gibbons was in his sweetest mood that night, and Canfield made many anxious inquiries as to his views of life and death, and announcing his willingness to lace the grim conqueror for the sake of his country and God, relapsed into silence. That was our last night together. In the terrible carnage of the next day’s charges up Marye's Heights, Gibbons fell mortally wounded in the thigh, and while attempting to carry him off the field, his lieutenant (Canfield) was shot through the head, and fell dead on the field of honor. Others bore off his captain, who died five days later; but Lieut. Canfield had kept his word and more than his word, for he had won death and distinction. His remains are supposed to have been buried on the battlefield where he fell, and probably are among the bones of our boys in the vast number of “unknown” on that fair green field of Fredericksburg, where the Rappahannock sings their lullaby, unmindful of the many ancient strifes upon its banks; and the tomb of Mary, mother of Washington, is surrounded by the graves of thousands who bravely fell to preserve the liberty transmitted to them by her son. |

||