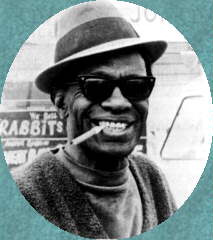

LIGHTNIN' HOPKINS

March 15, 1912 - January 30, 1982

Birthplace: Centerville, Texas

Lightnin' Hopkins was a Texas blues great whose career spanned six decades and who, in all

probability, made more recordings than any other blues artist. His was a prolific

songwriter, a master raconteur, and a convincing performer. His guitar style, with its

ragged rhythms and carefree collection of meter and structure could never be considered

conventional. But it did possess a remarkable and authenticity, and it almost always

seemed the ideal vehicle to carry his and complement his dry, sagebrush-scratched vocals.

When it came to recording or performing, Hopkins often improvised with and humor. He made

up verses as he went along, or else altered lyrics as he saw fit. Hopkins was, in the end,

a tremendously important blues figure one of the most influential country blues artists of

the post-World War II period. In Texas only Blind Lemon Jefferson and T-Bone Walker have

had as much impact on be state's blues legacy.

Hopkins was born in Centerville, Texas, and learned guitar from his older brother Joel,

himself a blues musician. In 1920, when he was eight years old, Hopkins met and performed

with Blind Lemon Jefferson at a country picnic. The opportunity to play alongside

Jefferson left a profound mark on the young Hopkins. The incident so strengthened his

desire to become a blues musician that by the time he was in his early teens he was

accompanying his popular blues vocalist cousin, Texas Alexander, at house parties and

picnics and traveling all over East Texas. Hopkins continued to perform on and off with

Alexander until the mid-'30s when Hopkins was sent to a prison work farm for an unknown

offense.

Upon his release, Hopkins resumed his partnership with Alexander. They performed on

Houston street corners and in small clubs, and periodically traveled to Mississippi and

other southern states to play parties and juke joints. In 1946 a talent scout for Aladdin

Records discovered the duo in Houston and offered them a recording contract. Hopkins

followed up on the offer; Alexander didn't. When Hopkins cut his first songs later that

year in Los Angeles, it was with Wilson "Thunder" Smith, a Houston pianist, not

his cousin. During Hopkins's debut recording session, he was given the nickname

"Lightnin' " and Aladdin billed the duo as Thunder and Lightnin' on its first

releases.

Hopkins tasted success with the song "Katie May," which became a hit in the

Southwest. Aladdin called Hopkins and Smith back to Los Angeles the following year to make

more recordings. A second session later in 1947 was scheduled just with Hopkins. Given his

erratic approach to singing and playing the blues, Hopkins was at his best when he

performed with no accompaniment.

In all, Hopkins recorded forty-three sides for Aladdin. At the same time he was also

making records for Gold Star in Houston, occasionally recording the exact same songs he

cut in L.A. with Aladdin. During his career, Hopkins recorded for more than twenty labels,

making his discography one of the longest and most complicated in blues history.

Hopkins recorded regularly from 1946 to 1954, cutting dozens of songs, not only with

Aladdin and Gold Star but also with Mainstream, Mercury, Herald, and other labels. But

because none of Hopkins's releases ever sold remarkably well, his first recording phase

ended as interest in electric blues, particularly Chicago- made, picked up. Hopkins went

back to playing Houston clubs and parties until be was rediscovered by blues historian and

record producer Sam Charters in 1959. Under Charters' guidance, Hopkins resumed his

recording career, this time cut- ting material for Folkways, Prestige/Bluesville,

Arhoolie, and other labels in the 1960s.

Though Hopkins continued to work out of Houston and played there often, he broadened his

popularity considerably during the folk-blues revival of the early '60s. In the year after

meeting Charters, Hopkins went from playing small blues joints in Houston to sharing a

bill at Carnegie Hall in New York with Pete Seeger and Joan Baez. His raw blues sound and

narrative talents made him a popular performer on the concert and coffeehouse circuit and

a regular at folk and blues festivals. In 1964 he toured with the American Folk Blues

Festival package in England and continental Europe and afterwards returned to Carnegie

Hall. The following year he was a featured performer at the Newport Folk Festival.

His simple, traditional interpretation of the blues influenced a number of white

folk-blues artists. By the late 1960s, Hopkins's appeal had even begun to pour over into

rock territory. For one Bay Area concert, Hopkins headlined over the popular acid-rock

group Jefferson Airplane. At another he performed with the Grateful Dead. All along,

Hopkins kept on recording for practically any label that would pay him cash up front.

Hopkins remained busy as both a recording and performing artist in the 1970s. He

contributed to the soundtrack of the movie Sounder in 1972, appeared in a number of blues

documentaries, played the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival and Carnegie Hall

again, toured Europe, recorded for the Sonet label, and continued to maintain his

traditionalist blues style, even though interest in his brand of country blues had, by the

late '70s, all but dried up. Hopkins was inducted into the Blues Foundation's Hall of Fame

in 1980. He died of cancer in 1982.