*

*Saints, Mermaids & Phoenicians Contents

Cornish Legends

Saints, Mermaids & Phoenicians

*

*

Cornish Wells

Mermaid legends can be found in both Cornwall and other Celtic countries, but where do they come from and why have they lasted the test of time?

When the Phoenicians first came to Cornwall they must have learnt to converse in order to barter. When the trading day was finished, the traders and buyers probably sat round the fire enjoying the local hospitality and exchanging tales. The Cornish had their stories of Giants, Knockers and other spirits, and the Phoenician’ s probably told of their great sea journeys and to add a little excitement probably claimed to have met the “tritons” as they called the mermen and other strange creatures.

They may even have traded a vase showing a typical floral pattern and the triton

motif similar to the one on the left, found by archaeologists in Etruria one of the

Phoenician city-states and which is believed to have been made around the year

540BC.

They may even have traded a vase showing a typical floral pattern and the triton

motif similar to the one on the left, found by archaeologists in Etruria one of the

Phoenician city-states and which is believed to have been made around the year

540BC.

The Phoenicians would have set up makeshift alters in order to worship their gods El and Baal and the goddess Astarte / Asherar-yam, our lady of the sea. Little figurines such as the Bull would have been used and in the case of the goddess the symbol may have been as simple as a coin. Coins found at one of the ancient Phoenician sites have a Mermaid on them and this is believed to have been a representation of Astarte who was also linked with mother goddesses of neighbouring cultures, in her role as combined heavenly mother and earth mother. Cult statues of Baal and Astarte in many forms were left as votive offerings in shrines and sanctuaries as prayers for a good harvest and by the infertile wishing for help. It may be that the tossing of coins into fountains and Wells is a result of the goddess being put on a coin by the Phoenicians.

Many of these shrines are still to be found at the sites of springs or wells around the Mediterranean and I have visited them in both Greece and Turkey and found offerings still being left.

In Celtic tradition water was of great importance and archaeologist have found lakes and wells a great source for finds dating from the Celtic age. In the lake on the Isle of Anglesey, objects from all parts of Briton were found that dated to the period when the Romans were driving the Celts westward. These included the usual coins, pins etc as well as Slave chains and a complete chariot. Whilst in Coventina's Well at Carrawborough, Northumberland the finds included replicas of human heads, as well as over 14,000 coins, a bronze dog and horse, glass, ceramics, bells and pins.

Strabo cites Posidonius as mentioning a "sacred precinct and pool" in a region near Toulouse in France. Treasure taken from it and later pillaged by the Roman consul Caepio in 102BC, comprised an estimated 45,000 kilograms of gold and nearly 50,000 kilogrammes of silver.

Spirits have always been associated with springs and wells from the earliest times, and the Druids used sources of water as entrances to Other worlds. In ancient stories such as "Branwen Daughter of Llyr" a giant emerges from the lake with a cauldron on his back whilst a more famous tale is of the lady of the lake giving the sword Excalibur to Arthur. (Ref.1)

In ancient Gaul the custodian of the healing spring was a fertility goddess, always beautiful, sometimes dangerous, and these female deities have metamorphosed over time into the faeries of popular tradition.

“Ladywells” are often connected with sightings of a strange lady, a ghostly figure, perhaps of the displaced well spirit or priestess. Whilst the water spirits in Gaul were known as 'Niskas' * or 'Peisgi', the word may derive from Old Celtic 'peiskos' or Latin 'piscos', both meaning fish. In Cornwall the strange lady turned into a 'mermaid' who enticed men into her underwater world.

In Cornwall there are a number of Wells which are still used by people seeking help, and on a recent visit to Alsia Well near St Buryan I found that votive offerings including coins had been left, the Phoenecian custom having been adopted by the Cornish as part of their own religion and the mermaid legends passed down through the ages.

Many of Cornwall's wells have legend associated with them. I have chosen to look at the one associated with Madron close to Penzance.

Of this well we have the following notice by William Scawen, Esq., Vice-Warden

of the Stannaries. The paper from which we extract it was first printed by

Davies Gilbert, Esq., F.RS., as an appendix to his “Parochial History of

Cornwall.” Its cornplete title is, “Observations on an Ancient Manuscript,

entitled ‘Passio Christo,’ written in the Cornish Language, and now

preserved in the Bodleian Library; with an Account of the Language, Manners, and

Customs of the People of Cornwall, (from a Manuscript in the Library of Thomas

Artle, Esq., 1777)”

“Of St Mardren’s Well (which is a parish west to the Mount), a fresh true story of two persons, both of them lame and decrepit, thus recovered from their Infirmity. These two persons, after they had applied themselves to divers physicians and chirurgeons, for cure, and finding no success by them, they resorted to St Mardren’s Well, and according to the ancient custom which they had heard of, the same which was once in a year—to wit, on Corpus Christi evening—to lay some small offering on the altar there, and to lie on the ground all night, drink of the water there, and in the morning after to take a good draught more, and to take and carry away some of the water, each of them in a bottle, at their departure. This course these two men followed, and within three weeks they found the effect of it, and, by degrees their strength increasing, were able to move themselves on crutches. The year following they took the same course again, after which they were able to go with the help of a stick; and at length one of them, John Thomas, being a fisherman, was, and is at this day, able to follow his fishing craft. The other, whose name was William Cork, was a soldier under the command of my kinsman, Colonel William Godolphin (as be has often told me), was able to perform his duty, and died in the service of his majesty King Charles."

When one reads accounts like this one it is understandable that our ancestors believed in the power of the water spirits. Gildas describes pre-Christian Britain as a place of diabolical idolatry. He indicates that the ancient Britons worshipped more idols than the Egyptians in their heyday! He says that the people paid divine honour to mountains and rivers.

It is sometimes said that the religion of Britain in the early centuries was Druidism. Actually, it seems that the Druids were just the teachers of their day. They presided at religious ceremonies, but it is not clear that they had their own religion. They seem to have taken over whatever religion was traditional in any given place.

In The Gallic Wars Julius Caesar gives us a few snippets of information about the Druids. His observations relate to Gaul, but he does say that Druidism originated in Britain and crossed the Channel from here.

He also notes that those who wanted to improve their knowledge of Druidism generally went to Britain to study it.

The druids would also use water to foretell the future. Plutrarch the Greek historian writing about the Druids in his "Life of Ceaser" states:

"From the several waves and eddies which the sea, river, or other water exhibited when put into agitation, after a ritual manner they pretended to fortell with great certainty the event of battles." (Ref. 2)

But the people would also seek

advice from the Druids about more mundane things like their own health and

welfare. The holy man would consult with the water spirit and would be shown a

sign for him to interpret. The Water Spirit usually took the female form and in ancient

Cornwall the custodian of the healing spring was a fertility goddess, always beautiful, sometimes

dangerous who metamorphosed over time into the mermaids of popular tradition who

could change their form. Many of these wells were known as “Ladywells”

and are often connected with sightings of a

strange lady, a ghostly figure, perhaps of the displaced well spirit or

priestess. Whilst the water spirits in Gaul were known as 'Niskas' or 'Peisgi',

the word may derive from Old Celtic 'peiskos' or Latin 'piscos', both meaning

fish. Sir

F. Palgrave says:- "The Nixie... are in most respects like the Cornish Mermaid."

Madron is one of these "Ladywells" and in her paper Madron Well: 'the Mother Well' (Ref. 4) Chesca Potter states the following:- "The name Modron (Ref.5) is used in Celtic mythology in a specific sense. It does not mean Mother as most of us think of her. Modron is Mother of the 'virgin', or maiden. Modron is the earth mother, sometimes depicted as a Black Goddess/Madonna, black being the symbolic colour of earth, the underworld and death. The Mother represents the dark or waning moon, and her daughter, the bride or virgin is the new and waxing moon This female polarity is a more ancient division of the aspects of the Goddess than the later maiden, mother, hag."

In his Stories and Folk – Lore of

West Cornwall, William Bottrell describes a visit made by the Penzance Field

Club to Madron Well around 1880. He asked the old lady who looked after the well

and acted as their guide what the locals thought of St Madron’s Well. She

replied that she had “never heard that a saint had anything to do with the

water except from somebody who told her there was something in a book about it;

nor had she or anybody else heard the waters called St Madron’s Well, except

by the new gentry, who go about giving new names to the places, and think they know more than the people

who have lived here since the world was created.

We enquired if the people ever went to the old chapel to perform any ceremony?

Not that she ever heard of; Morvah folks and others of the Northern Parishes who

mostly resort to the spring pay no regard to any saint or to anybody else,

except some old woman who may come down with them to show how everything used to

be done. We were also informed that there is a spring in some moor in Zennor,

not far from Bosporthenes, which is said to be as good as Madron Well, and that

children are often taken thither and treated in the same way.” (Ref. 6.)

The noted antiquarian and vicar of Ludgvan Dr William Borlaise, wrote the following on the subject of the Cornish visiting the local Wells* in the latter half of the seventeenth century:

"A way of divining and still usual among the vulgar of Cornwall, who go to some noted well on particular times of year, and there observe the bubbles that rise, and the aptness of the water to be troubled or to remain pure, on their throwing in pins or pebbles and then conjecture what shall or shall not befall them." (Ref.7)

Sancreed and Madron are both close to the Town of Penzance and on June 24th they celebrate Midsummer's Day. But at Penzance it falls in the middle of the Galowan festival. The ten days of Golowan brings the past and present together in Penzance's community celebration of the traditional Feast of St. John. Many of those taking part will not realise that in effect they are celebrating a festival which goes back in time through the Roman Goddess Diana to the Greek goddess Artemis to the Phoenician Goddess Astarte / Asherar – yam all of whom were celebrated on June 24th by their different worshippers. St John’s Eve was always a major fire festival which included dancing in the street with lighted tar barrels on poles being swung around the heads of the dancers as they went down the street. In the late eighteen hundreds this part of the celebrations was brought to an end when the insurance companies refused to pay out on property which caught fire in Penzance. (Ref. 8)

Some who knew the true meaning of the day visited the Well at Madron. Young people dropped pins into the waters to see if they touched. Others visitors tied scraps of rag to a nearby bush just as their fore-bearers had done before, in the hope of a cure for some illness. The legend has been passed down through time and in Cornwall people seeking help still visit what they think is the sight of the Madron Well.

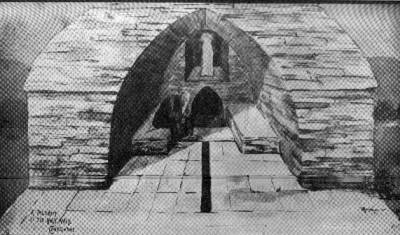

However, when my wife was a young girl her father would often take her for walks to the well. Recently we made a return trip and she was astonished to find that people seemed to be leaving their votive offerings at the wrong place. What is more, a lot of the offerings where scraps of non bio-degradable material tied to the trees which meant that they could not rot and relieve the sufferer of their illness. We hunted around and found what she is convinced is the actual well silted up and not close to the the site now used. The two photos above show Madron on the left with Sancreed well on the right.

On visits to other wells I have found that votive offerings including coins have also been left, the Phoenician custom having been adopted by the Cornish as part of their own religion and the legends passed down through the ages, just as it was by the Druids before Christianity came, and even with its arrival things did not change until the coming of the Saxons and with them the coming of the Roman Church almost a thousand years after Christianity had first been brought to Celtic Briton by Joseph of Arimathea and the other followers of Jesus. (You will find more of this on later pages).

With the arrival of the Roman Church around 940A.D. the old clergy were driven out of Cornwall to either Ireland or Brittany. With their departure new versions of the legends were written and placed in the churches. In these versions the Celtic saints seem always to have chosen the neighbourhood of a spring as a site for a settlement - sometimes no doubt - because the spring was an object of what they referred to as heathen worship, which they desired to supersede by surrounding it with Christian associations, sometimes simply because pure water is a necessity of human life. At Madron one of the ancient chapels can be seen close to the site of the well. although it lacks a roof its alter is still in place.

In the manuscripts detailing the lives of

the Cornish saints many of their holy wells

were regarded as possessing

healing powers. In the old Cornish miracle play “The Life of St. Meriasek.”

it is said that the saint even created the well by causing a miraculous fountain to spring up at Camborne, and prays

In endeavouring to Christianise the feelings of veneration with which,

from time immemorial, these wells were regarded, the Saxons were acting

not only wisely and prudently (consecrating, instead of destroying natural born

instincts,) but entirely in the spirit of Holy Scripture

The dual aspect of the Goddess also passed over very clearly into Christianity. St Anne is the Mother of the Virgin, who in turn is the Mother of the son or sun. You will find a well dedicated to St Anne at Looe in Cornwall, but the most famous one is in Brittany and it is there that we must travel on the next step of our journey.

"The Druids" Ward Rutherford

Ancient and Holy Wells of Cornwall by M & L Quiller Couch. ISNB 0 95128225 5. Pub 1994.

article entitled the "Popular Mythology of the Middle Ages" which was published in "Quarterly Review No 44 in 1820

Madron Well: 'the Mother Well' by Chesca Potter

The archetypal meanings of Modron have been well researched by Caitlin Matthews for her forthcoming Arkana publication on the Mabinogion.

"Traditions & Hearthside Stories of West Cornwall", 2nd Series.p240 By William Bottrell.

"Borlaise Papers" Royal Cornish Institute Library, Truro.

"A History of Penzance" P.A.S. Poole.

* The illustration is of St Constantines Well which was buried by the sands of Harlyn Bay in the eighteenth century but in 1911 it was uncovered by a Mr Penrose Williams and the sketch made before it was again buried..