The Winsted CT 1955 flood of the Mad River after hurricanes Connie and Diane

The Flood of 1955 was one of the worst floods in Connecticut's history. Two back-to-back hurricanes saturated the land and several river valleys in the state, causing severe flooding in August 1955. The rivers most affected were the Mad River and Housatonic River, and Still River> in Winsted, the Naugatuck River, the Farmington River, and the Quinebaug River. The towns that suffered much loss include Farmington, Putnam, Waterbury, and Winsted. 87 people died during the flooding, and property damage across the state was estimated at more than $200 million, in 1955 figure.

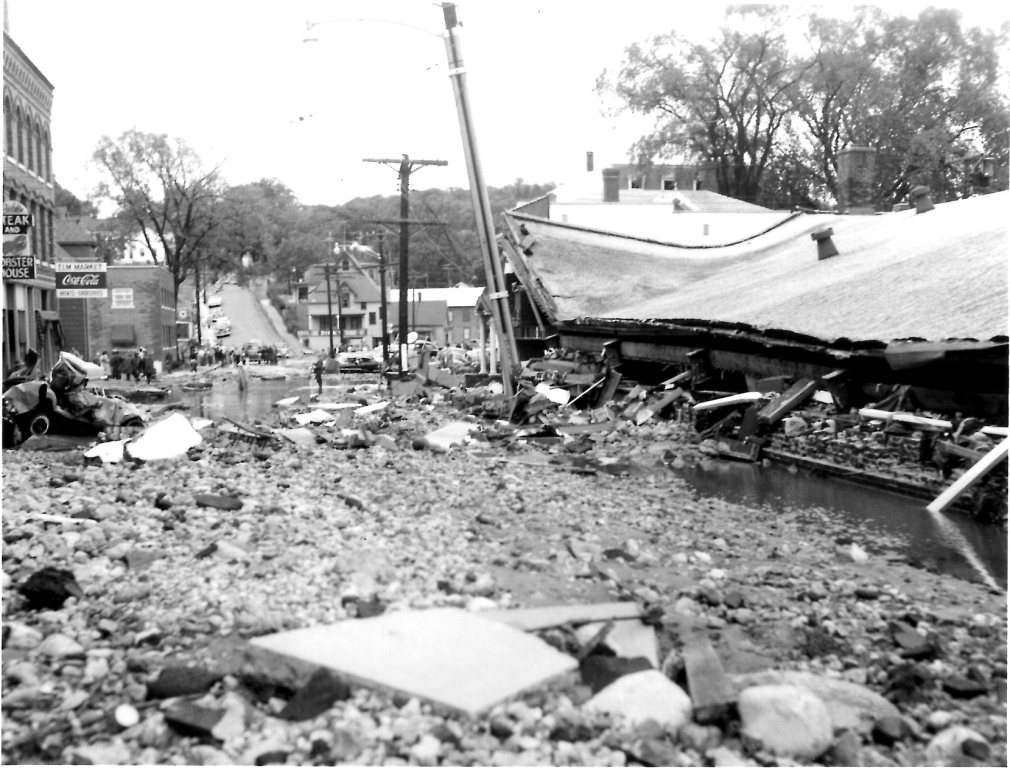

On Aug. 19, 1955, nearly all of the Main Street shops were gone, destroyed by a flood that struck Winsted and 70 other Connecticut cities and towns. By the time it was over, about 80 people were dead and 4,500 injured around the state. Various reports put the property damage at around $300 million. The death toll was highest in Waterbury, where 30 people died, 26 of them residents of 13 houses that were swept away on North Riverside Street. But no town was as devastated as Winsted, which lost its downtown.

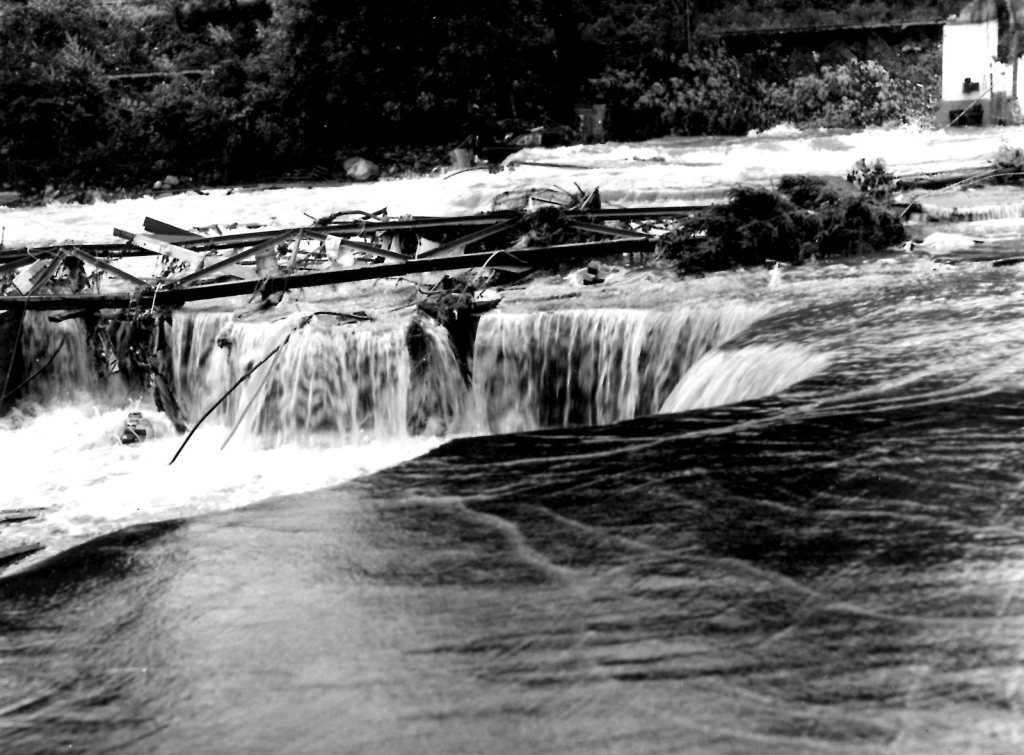

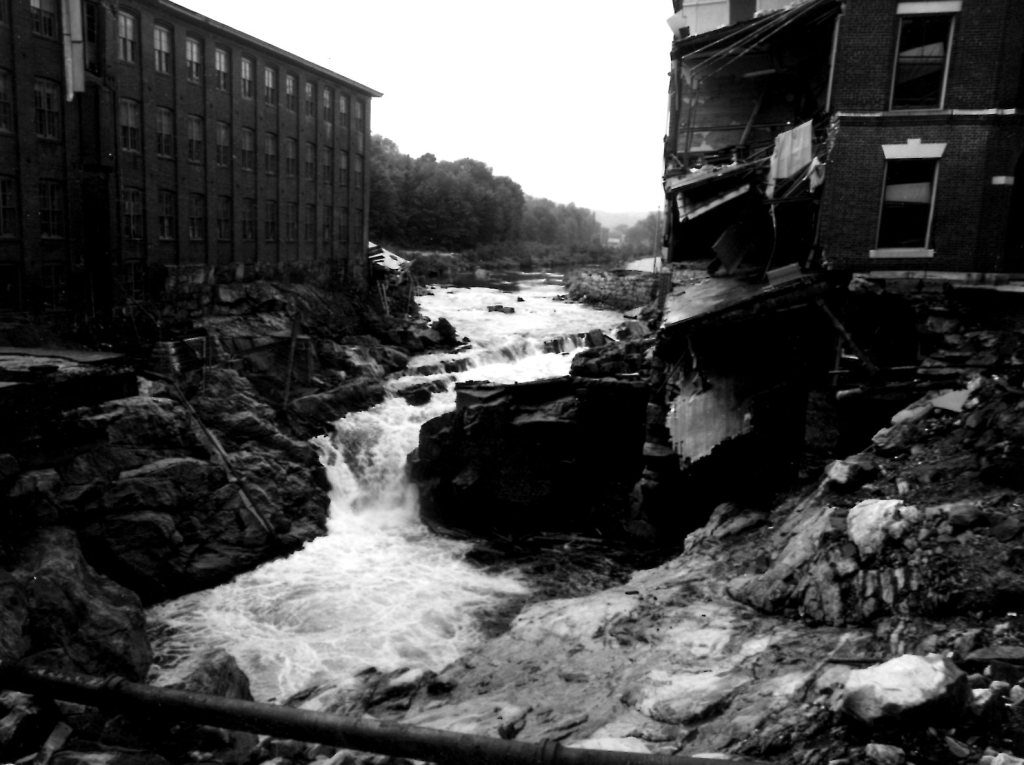

The Mad River, fed by Highland Lake, which sits just above Winsted, flows along Main Street, and when the river flooded, it took much of the downtown with it. The south side of Main Street, which backs onto the river, was virtually washed away. The damage was so bad that Winsted never fully rebuilt and just paved over the street where the businesses and tenements once stood.

Main Street today seems out of balance, with stores on one side of the four-lane street and nothing but road and the river on the other. The author, John Hersey, noted for his reporting of the devastation of Hiroshima, also wrote about Winsted for The New Yorker.

''All the way from Norfolk, the Mad River was brimming,'' he wrote in an article a month after the flood. ''Along Main Street, it was 15 feet above its normal level, and the water was 10 feet deep in the street itself. It was literally ripping up Main Street. The pavement and the sidewalks were being sliced away and gutted six feet deep. The water had broken the plate glass windows of most of the stores along the street and had ruined their stocks. Winsted Motors, a Buick showroom and service station that had straddled the river high up the street, had been completely demolished and its new and used cars were rolling all the way downtown, and its roof had lodged itself in midstreet right in front of the town hall.''

The flood was caused by two tropical storms, the remnants of Hurricanes Connie and Diane, that, one after the other, saturated the state. ''Connie dropped between 5 and 8 inches of rain on the 13th, then along came the slow-moving Diane just 5 days later to add 15 to 20 more inches to the already swollen rivers and streams,'' said David Vallee, the science and operations officer for the National Weather Service in Taunton, Mass.

Also hit hard were Naugatuck, Torrington, Thomaston, Beacon Falls and Ansonia, flooded by the Naugatuck River; the Unionville section of Farmington, New Hartford and Collinsville on the Farmington River; and the northeastern towns of Putnam, Thompson and Danielson, which were severely damaged when a dam burst in Massachusetts, causing the Quinebaug River to flood those towns.

In the Sept. 17, 1955, issue of The New Yorker, Mr. Hersey also wrote that, in Winsted, ''nearly all the Main Street stores backing on the watercourse were surmounted by rickety wooden tenements, mostly three or four stories high, many of them connected to each other on the river side by continuous wooden porches.'' These wooden structures were torn apart as the Mad jumped its banks in the early morning of Aug. 19.

Winsted before the flood, with the storefront tenements described by Mr. Hersey, is preserved on a film made in 1948 by Carmine Cornelio, a resident, to show his American hometown to family and friends in Italy. The color film shows a narrow two-lane Main Street with many small shops. The few surviving landmarks are the stone and brick churches, banks, schools, factories, post office, town hall, public library, movie house and electric-company office that withstood the flood.

Gov. Abraham Ribicoff first learned of the flooding shortly after 1 a.m. on Aug. 19, when Mayor William Carroll of Torrington telephoned him to ask for state assistance. The governor ordered National Guard troops to Torrington, then tried to ride there in a state police cruiser, but he couldn't get past Burlington. At about the same time in nearby Winsted, the police and firefighters began going door to door along Main Street, telling residents to leave for higher ground. As the waters rose, the warnings turned into rescues. One firefighter, Vincent O'Brien, wrote years later of how he and two other men took a woman and her four young children out a side window onto the next rooftop and led them to safety by going roof to roof. ''Sometimes the roof was higher, then lower,'' Mr. O'Brien wrote. ''Some were so steep, we had to walk the peak and I prayed no one would lose their footing.'' After what seemed like hours, he wrote, the family and their rescuers found a dry, empty apartment on the fourth floor of one of the tenements. Mr. O'Brien also recalled seeing the back end of a Chevrolet dealership torn out and ''the new cars popping through the hole and diving into the river. They looked like young whales leaping out of the water only to dive to the bottom again to die.''

Responding to Governor Ribicoff's request for federal help, President Eisenhower came to the state the following Tuesday and said he would call a special session of Congress to speed aid to flood-ravaged northeastern states if necessary. The president said Connecticut's share would be about $25 million. The next day, Mr. Ribicoff ordered $34 million in state building projects halted to preserve credit for flood relief and rehabilitation and said rebuilding would be financed by bonding, rather than tax increases. But later, the General Assembly increased sales, liquor and cigarette taxes for nine months to finance some rebuilding.

Before much reconstruction could be accomplished, the state was hit by a second flood on Oct. 15 and 16, causing an additional $20 million in damage, mostly to towns in western and southwestern Connecticut, and killing 17 more people. There was flood damage in more than 60 towns this time, including 39 hit in August.

In Winsted, a concrete wall was built to deal with future floods. In the next decade, federally financed flood-control dams were built near Winsted and other communities. But as Mr. Vallee of the National Weather Service pointed out: ''Dams are built to withstand six to eight inches of runoff, to control flooding, not prevent it. If heavy rains from tropical storms like Connie and Diane were to soak the state again over a few days, there would be major flooding, though not as severe as 1955.''

The flooding was caused by the rains from two hurricanes, Hurricane Connie and Hurricane Diane. On August 11, Hurricane Connie swept through the East Coast—missing Connecticut, but bringing about 4 to 6 inches of rainfall to the state on August 13. Hurricane Diane came through the following week. The path of Hurricane Diane came closer to Connecticut, after soaking up waters from the Atlantic Ocean. Once the hurricane reached the coast of Long Island, it dumped an additional 13 to 20 inches of rain on Connecticut over a two-day period.

The heavy rains on already-saturated ground made several rivers in the region begin to overflow. Massachusetts, New York, and Rhode Island experienced flooding, but Connecticut was hardest hit in New England. New Jersey, Delaware, and Pennsylvania were also hit by flooding caused by the two hurricanes. Two months later, another storm brought an additional 12 to 14 inches of rain to New England—hitting some communities that had been affected by the August floods, and others that had escaped

The rains poured down for much of the day Thursday, August 18, starting at about 3:00 AM. By 11:00 PM, the Shepaug River and brooks in the western portion of the state had begun to overflow their banks. In Waterbury, the water reached an estimated 35 feet in places, and was reported to have moved at rates up to 50 miles per hour. While major rivers, such as the Connecticut River, had flood control measures in place, smaller rivers and brooks did not. That is where the major damage occurred. The Housatonic River in Western Connecticut reached 24.50 feet—its highest levels until October 1955, when it again reached 24.50 fee. tOn noon of August 20,1955 President Eisenhower declared Connecticut a "major disaster area"

The Winsted Evening Citizen reported that 95 percent of the city's businesses were destroyed or severely damaged; 170 of the city's 200 retailers were wiped out as Winsted lost 18 grocery stores, 9 barbershops, 16 restaurants and taverns, 8 package stores, 3 small hotels and several car dealerships. The four-story Clifton Hotel floated off its foundation and into the river. It landed on a town baseball field, its first two floors gone but the upper two intact, Mr. Hersey reported.

Police forces, volunteer firefighters, Connecticut National Guard members, the Coast Guard, and average citizens worked together to rescue people from their homes and other buildings where they became stranded. At 1:00 AM on August 19, as the water began rising over the banks of several rivers, Gov. Abraham Ribicoff mobilized the National Guard.

More than 25 helicopters—from the U.S. Navy and local companies like Sikorsky were used to rescue hundreds of people from rooftops and tree branches where they clung to life. The flood hit the Naugatuck river with such fury that as many as 500 people in the Waterbury area had to be rescued by helicopter.

The following damage figures were outlined in the state report three months after the flood:

- 668 dwellings were totally destroyed

- 2,460 suffered major damage

- 5,213 suffered minor damage

- 507 "industrial establishments' suffered $88.4 million in damage to buildings, machines, and materials

- 1,436 commercial establishments suffered $45.5 million in damage

- 922 farms reported losses of $2.5 million (not including damage to the land itself)

- public property damage was estimated at $36.8 million

In New England, more than 200 dams suffered partial or total failure. More than 50 coffins floated away from a cemetery in Seymour. The state shipped in 300 temporary housing units from Groton, to help provide shelter for the newly homeless

The floods prompted the United States Army Corps of Engineers to build $70 million worth of dams and flood walls along several Connecticut rivers. In 1960, the Army Corps built the Thomaston Dam. The Thomaston Dam on the Naugatuck River is one of the largest flood control measures erected by the Army Corps of Engineers. Following the building of the Thomaston Dam; the Corps built the Northfield Brook Dam, in 1965, and the Colebrook Dam, in 1969.

Claire Vreeland of Colebrook lived with her husband and two small children in one of several housing units built for veterans near Route 8, which crosses Main Street on the east end of the town. ''We had returned from a vacation the previous afternoon and slept through the rainy night,'' Ms. Vreeland said. ''In the morning, my husband left for work in Windsor Locks, but was back in a few minutes to tell us the roads were not passable. ''Since we were just back from vacation and had little to eat in the house, I normally set out for Main Street to buy some bread and milk, but I was stopped by an armed National Guardsman who told me to go home.''

Among the buildings damaged was the main office of the Gilbert Clock Company. Judy Pavlak and her husband, Ray, were temporarily living with Ms. Pavlak's parents. ''My father was a supervisor at Gilbert and not long after he had left for work, he came home and announced, 'No work today.'''

By morning, the Mad River was 15 feet above its normal level of 5 to 6 feet, and water was 10 feet deep in the street. With bridges washed away, without electricity, drinking water and telephone service and with its downtown devastated, Winsted was ''completely cut off from the world,'' a Hartford Times article reported. Robert McCarthy, an Evening Citizen reporter, said his city ''resembled a twisted, tortured mass.''

In little over a week, two hurricanes passed by Southern New England in August 1955 producing major flooding over much of the region. Hurricane Connie produced generally 4-6 inches of rainfall over southern New England on August 11 and 12. The result of this was to saturate the ground and bring river and reservoir levels to above normal levels.

Hurricane Diane came a week later and dealt a massive punch to New England. Rainfall totals from Diane ranged up to nearly 20 inches over a two day period. The headwaters of the Farmington River in Connecticut recorded 18 inches in a 24-hour period. Both of these accumulations exceeded records for New England. The same is true of much of the flooding that resulted from these massive rainfall amounts.

Over the course of four days in August of 1955, tropical storms Connie and Diane dumped 14 inches of torrential rain on Connecticut and other states along the eastern seaboard. In Winsted, streams and riverbeds became overwhelmed from years of accumulated debris and caused the Mad and Still rivers to overflow. Highland Lake water raged over the spillways and heavily damaged everything in its path. The force washed away streets, sidewalks, buildings, bridges, electrical lines, sewer pipes, and water mains. Floodwater reached as high as 16 feet along Main Street, seven people lost their lives, and many businesses and homes were damaged or destroyed.

When the Mad River finally receded, it left behind silt, mud, and massive destruction. All of the buildings on the river side of Main Street were eventually demolished - from Division to Oak Street. State and federal agencies, as well as a score of volunteers, pulled together to bring Winsted back from disaster, but the massive cleanup effort took nearly five years to complete.

Following the 1955 flood the Army Corps of Engineers spent nearly 2 decades damming some of the most vulnerable rivers in Connecticut. The city of Winsted was arguably the most vulnerable area in the state before the great flood. Several times in the 1800s the Mad River flowed over its banks and flooded downtown. The Mad River, a tributary of the Still and Farmington Rivers, is now dammed in Winchester 2 miles west of Winsted on Route 44. In addition, Highland Lake, which is about 100 feet above the Mad River just southwest of downtown Winsted frequently overflowed its banks and added water to the typically swollen Mad River.

During the 1955 flood the Mad River was raging down from the hills of Norfolk while the Sucker Brook raged into Highland Lake sending water cascading from the lake into Winsted. The combination destroyed most of Main Street in town. The southern side of Main street was never rebuilt and was paved over.Besides the Mad River dam in Winchester the Sucker Brook dam along to the west of Highland Lake helps regulate the lake’s level and prevent more water from reaching the Mad River in downtown. The flood control for Highland Lake and the Mad River reduces flows on the Mad River which flows into the Still River and eventually the West Branch of the Farmington River.

The Farmington River surged to levels never seen before during the 1955 flood. On the West Branch of the Farmington River the Metropolitan District Commission had completed the Hogback Dam and the West Branch Reservoir behind it before the flood. Plans for the Colebrook River Dam were already in place when the flood occurred and the Army Corps took over the project for flood control purposes. The Colebrook River Dam in Hartland and Colebrook is a major part of the flood control system on the Farmington River. The watershed upstream, including the western Massachusetts towns of Becket, Otis, Sandisfield, Tolland, and Granville help feed Colebrook River Lake and the West Branch Reservoir.

The Army Corps maintains the flow leaving the Colebrook Dam for both flood control and low flow augmentation, according to the MDC. Both the lake and reservoir may be used as water supplies in the future according to the MDC. The combination of the flood control on the Mad River (Sucker Brook dam and Mad River dam) and the Colebrook River dam provides significant flood control on the Farmington River. Barring some type of catastrophic failure of the flood control system a flood like 1955 will not happen again in towns like Winsted, New Hartford, and Unionville. That said, if rain like August 1955 happened again, major flooding would be likely along the length of the river with devastating results likely.

The Naugatuck River flooded virtually every town from Torrington to Derby in 1955. Waterbury, Thomaston, Naugatuck, Ansonia, and Derby were particularly hard hit. 7 dams were constructed by the Army Corps which has significantly reduced the flow of the Naugatuck River particularly in times of heavy rain. The first 2 dams control the river north of Torrington. The East Branch Dam in Torrington and the Hall Meadow Brook Dam protect Torrington. Downstream the Thomaston Dam on the Naugatuck River provides additional protection. 3 tributaries of the Naugatuck downstream are flood controlled as well. Northfield Brook Lake, Black Rock Lake, Hancock Brook Lake, and Hop Brook Lake.

The Naugatuck River has barely reached flood stage in many locations following the construction of these dams. In fact in Beacon Falls the flood stage of 12 feet has only been exceeded 6 times in 50 years since the dams have been built. Of those crests 4 have been “minor floods”, 1 has been a “moderate flood” and 1 has been a “major flood”. Incidentally, of those 6 floods since 1955 on the Naugatuck River, 4 have occurred in the last 6 years!

The Quinebaug River was another river to rage on August 19th flooding downtown Putnam and sparking a spectacular fire at a magnesium factory in the city. The Quinebaug River actually begins in Union at Mashapaug Lake and flows north across the border into Massachusetts. The Quinebaug connects a number of small lakes in Massachusetts some of which occur naturally and others that exist now thanks to the Army Corps flood controls that have been built. The first dam on East Brimfield Lake covers the towns of Sturbridge, Holland and Brimfield. A second dam on the Quinebaug, the Westville Lake dam in Southbridge, also provides flood control on the river for the towns of Southbridge and Dudley.

The river continues south over the Connecticut border into Thompson where the massive West Thompson dam created West Thompson Lake and provides siginficant flood control for Thompson, Putnam and downstream towns through Jewett City. The dam is located just upstream of the confluence of the French and Quinebaug Rivers and several miles upstream of the confluence of the 5 Mile and Quinebaug Rivers in Putnam. The Buffumville Dam on the Little River (a tributary of the French) and the Hodges Village Dam on the French River in Massachusetts provide additional flood control on those rivers which are tributaries to the Quinebaug.

Additional flood controls in the Thames River basin include the Mansfield Hollow Lake Dam at the confluence of the Natchaug, Fenton, and Mt. Hope Rivers in Mansfield. The Natchaug River flows into the Shetucket River and eventually into the Thames. The dam was built before the 1955 flood which likely saved Willimantic from devastating flooding in August of 1955.

The 6 dams throughout the Thames River Basin have virtually eliminated the threat of a ’55 flood repeat. Still, we have seen significant flooding especially well downstream of the dams. The Quinebaug River in Jewett City overflowed its banks in the March 2010 flood causing significant damage. Since the flood controls have been in place the Quinebaug River in Putnam has yet to reach flood stage (10 feet). The crest on August 19, 1955 was 26.5 feet! The highest crest since the dams were built was 8.67ft on March 10, 1998

Hurricane Connie struck first, on August 12 and 13, sparing the state high winds but dropping up to 8 inches of rain, particularly saturating southwestern Connecticut. Five days later, Diane arrived, pouring another 16 inches of rain on the state, hitting the Naugatuck Valley and the northwestern towns hard; northeastern towns such as Stafford Springs and Putnam were also hard hit, the latter suffering from the Quinebaug Dam’s collapse in Southbridge, Massachusetts.

Some rivers in the Thames River basin are still vulnerable to flooding. The Yantic River is not flood controlled. Other rivers upstream of dams are also vulnerable. The Mt. Hope River in Ashford reached “major” flood stage in October 2005. The Willimantic River from Willimantic north through Storrs is also vulnerable having reached “major” flood levels in October 2005. The 2 highest crests for the river in Coventry remain the 1955 and 1938 floods.

The flooding on the Naugatuck River began upstream in Winsted when the Mad River exploded from its banks, destroying downtown Winsted. The surge of water continued downstream into Torrington, Thomaston, Waterbury, Naugatuck and Ansonia, destroying hundreds and hundreds of homes and factories. Dozens of people drowned as the flood moved south while hundreds waited to be rescued on their roofs.

Special 60th anniversary edition of the Republican American of the flood of 1955

Hurricane Diane was the costliest Atlantic hurricane of its time. One of three hurricanes to hit North Carolina during the 1955 Atlantic hurricane season, it formed on August 7 from a tropical wave between the Lesser Antilles and Cape Verde. Diane initially moved west-northwestward with little change in its intensity, but began to strengthen rapidly after turning to the north-northeast. On August 12, the hurricane reached peak sustained winds of 105 mph (165 km/h), making it a Category 2 hurricane.

Gradually weakening after veering back west, Diane made landfall near Wilmington, North Carolina, as a strong tropical storm on August 17, just five days after Hurricane Connie struck near the same area. Diane weakened further after moving inland, at which point the United States Weather Bureau noted a decreased threat of further destruction. The storm turned to the northeast, and warm waters from the Atlantic Ocean helped produce record rainfall across the northeastern United States. On August 19, Diane emerged into the Atlantic Ocean southeast of New York City, becoming extratropical two days later and completely dissipating by August 23.

The first area affected by Diane was North Carolina, which suffered coastal flooding but little wind and rain damage. After the storm weakened in Virginia, it maintained an area of moisture that resulted in heavy rainfall after interacting with the Blue Ridge Mountains, a process known as orographic lift. Flooding affected roads and low-lying areas along the Potomac River. The northernmost portion of Delaware also saw freshwater flooding, although to a much lesser extent than adjacent states.

Diane produced heavy rainfall in eastern Pennsylvania, causing the worst floods on record there, largely in the Poconos and along the Delaware River. Rushing waters demolished about 150 road and rail bridges and breached or destroyed 30 dams. The swollen Brodhead Creek virtually submerged a summer camp, killing 37 people. Throughout Pennsylvania, the disaster killed 101 people and caused an estimated $70 million in damage. Additional flooding spread through the northwest portion of neighboring New Jersey, forcing hundreds of people to evacuate and destroying several bridges, including one built in 1831. Storm damage was evident but less significant in southeastern New York.

Damage from Diane was heaviest in Connecticut, where rainfall peaked at 16.86 in (428 mm) near Torrington. The storm produced the state's largest flood on record, which effectively split the state into two by destroying bridges and cutting communications. All major streams and valleys were flooded, and 30 stream gauges reported their highest levels on record. The Connecticut River at >Hartford reached a water level of 30.6 ft (9.3 m), the third highest on record there.

The flooding destroyed a large section of downtown Winsted, much of which was never rebuilt. Record-high tides and flooded rivers heavily damaged Woonsocket, Rhode Island. In Massachusetts, flood water levels surpassed those during the 1938 Long Island hurricane, breaching multiple dams and inundating adjacent towns and roads. Throughout New England, 206 dams were damaged or destroyed, and about 7,000 people were injured.

Nationwide, Diane killed at least 184 people and destroyed 813 houses, with another 14,000 homes heavily damaged. Monetary losses totaled $754.7 million, although the inclusion of loss of business and personal revenue increased the total to over $1 billion. In the hurricane's wake, eight states were declared federal disaster areas, and the name Diane was retired.

The Connecticut National Guard was mobilized, and 16 helicopters plucked people off rooftops and out of trees. The US Navy, Sikorksy Aircraft in Stratford, Kaman Aircraft in Bloomfield, West Point, the First Army Corps of Engineers, and the US Marine Corps supplied additional aircraft, rescuing hundreds of people.

Civil defense and emergency shelters filled quickly, and the American Red Cross set up a central disaster headquarters in Hartford. Food drops were facilitated by C-47 planes from the New York Air National Guard and the Connecticut Air National Guard.When the event was over, according to the National Weather Service, 77 Connecticut lives were lost and property damage exceeded $350 million.

Hurricane Connie brought 4-6 inches of rainfall to New England on Aug. 11 and 12, 1955, saturating the ground. Then on Aug. 17, 1955, came the very wet, very windy Diane. In some places Diane dumped 20 inches of rain in two days.Hurricane Diane was bad -- almost as bad as Hurricane Carol, which hammered New England.

Hurricane Diane was the first hurricane to cost more than $1 billion in damage. Hurricane Diane affected the entire East Coast from North Carolina to Massachusetts. More than 100,000 New Englanders lost their jobs, as flooded mills and factories were forced to shut their doors. Seven thousand New Englanders were injured, more than 100 killed.

Connecticut got hit the hardest. Near Torrington, Conn, a weather station recorded 16.86 inches of rain within 24 hours, the highest in the state’s history.Diane split the state in two as bridges were swept away and communications severed. Connecticut lost 77 people of the 180 people killed as a result of Diane. Nearly 86,000 people in Connecticut were left unemployed.

Governor Abraham Ribicoff called the floods, reported in the August 20, 1955, edition of The Hartford Courant, “the worst disaster in the state’s history” and immediately declared a state of emergency. The state highway department reported that at least 17 bridges had been destroyed, isolating communities, and that numerous roads were blocked by rock slides. Major dams broke, railroad tracks were swept away, homes and businesses were destroyed, and drinking-water supplies were compromised. The Hartford Courant reported what eyewitnesses were seeing: “Lt. Col. Robert Schwolsky of the Connecticut National Guard reported from a helicopter: ‘I’ve never seen anything like Winsted’s Main Street. It looks like someone had taken cars and thrown them at one another,’” and another officer saw “a house, complete with lawn and landscaping, floating down the swollen river. A little later,… another house being swept by, smoke coming from its chimney.”

Main Street in Winsted, Conn., was nearly wiped out. A Connecticut National guardsman flew over in a helicopter and said it looked like someone had taken cars and thrown them against each other, the Hartford Courant reported. Another guardsman spotted a house floating down the river, complete with lawn and landscaping. Another floated by with smoke curling out of the chimney.

The >Still River flooded the struggling Gilbert Clock Co., and forced it to close its doors for good. The local newspaper reported 95 percent of Winsted businesses were destroyed or severely damaged.

In the flooded town of Putnam, Conn. Diane set fire to, then collapsed, a magnesium processing facility. As dawn broke, hundreds of barrels of burning magnesium drifted along the streets before exploding. In Waterbury, 26 people died when Diane washed away 13 houses in one neighborhood.

The hurricane washed out the Horseshoe Dam in Woonsocket, R.I., dislodging coffins from historic cemeteries. It also damaged wire and rubber factories, throwing 6,000 of Woonsocket’s 50,000 residents out of work. The Blackstone River swelled to a width of a mile

In Massachusetts, Hurricane Diane washed away the historic Old North Bridge over the Concord River. Thirteen people were killed, mostly by drowning. In Worcester, Hurricane Diane destroyed flooded shoe factories and threw 10,000 workers out of their jobs. The Longmeadow cricket courts were flooded, delaying the Davis Cup.

Eight states were declared federal disaster areas. National guardsmen dropped food to stranded flood victims from C-47 airplanes. Guardsmen in helicopters plucked people off of roofs and out of trees. Donations to help the victims came from around the world.Never again would a hurricane be named Diane.

In 1956, Congress passed the Federal Flood Insurance Act, creating federal flood insurance, but didn’t fund it. A national flood program would have to wait until 1968. Hurricane Diane also led to the creation of the National Hurricane Center.