|

CHRIST AND VIOLENCE

BY KOSTY BANDALY

TRANSLATED BY IBRAHIM ABOUD

Kosty Bandaly is a leading

figure in the Orthodox Church of Antioch; he published for decades on

issues relating to theology, psychology, sexuality, youth, and family.

This article, written in 1963, was posted lately on the website of the

Orthodox Youth Movement of Antioch (www.mjoa.org) to commemorate the works

and contributions of Mr. Bandaly. With so many reactionary publications

for and against war, which only serve to confuse the Orthodox mind with

thoughts foreign to our history and theology, one finds comfort in hearing

the serene voice of Antioch from the mouth of one of its great veterans.

THE POSITION OF

VIOLENCE AND ITS SOURCES:

Violence, whatever shape it takes, whether by an individual or a

collective, if its aim is to cause material or psychological damage to the

other, or if it were a response or reaction to an earlier act of violence,

usually assumes one spiritual position: to consider the other an obstacle

that must to be removed or debased. The violent one views the other as a

thing that must be destroyed, and not as a person that should be

respected. The sources of violence are various: some of it has to do with

love for power which accepts no opposition whatsoever, and makes no weight

of the opinion of the other or his/her existence. Another source may be

hatred, animosity, love for vengeance and inflicting harm. Another is fear

of others which causes for aggression against them to prevent some future

possibility of an attack by them, in accordance with the popular saying:

“have him for lunch before he has you for supper.” This relationship

between fear and violence is apparent in animals as realized from the

observations of psychoanalyst Maryse Choisy with regard to the behavior of

lions . Another source would be for an individual or a group to try to get

rid of a feeling of guilt by tossing that guilt on another individual or

group which becomes the “sacrificial ram” that receives all hatred.

THE TEACHING OF

CHRIST ON VIOLENCE:

It is obvious in this case that Christ rejects violence, as it is clear in

many passages from the Gospel. We hear him say in the sermon on the

mountain: “Blessed are the meek: for they shall inherit the earth”

(Matthew 5:5), “Blessed are the peacemakers: for they shall be called the

children of God” (5:9), “You have heard that it was said by them of old

time: You shall not kill; and whosoever shall kill shall be in danger of

the judgment. But I say unto you, that whosoever is angry with his brother

without a cause shall be in danger of the judgment…” (5:21-22). “You have

heard that it had been said: An eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth.

But I say unto you, that you resist not evil: but whosoever shall smite

you on your right cheek, turn to him the other also” (5:38), and “You have

heard that it had been said: You shall love your neighbor, and hate your

enemy. But I say unto you, love your enemies, bless them that curse you,

do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use

you, and persecute you” (Matthew 5:43-44), and he commanded his disciples

saying: “Behold, I send you forth as sheep in the midst of wolves: be

therefore wise as serpents, and harmless as doves” (10:16).

The apostles also taught the same teaching; the apostle Paul wrote:

“Recompense to no man evil for evil” (Rom 12:17), “Bless them which

persecute you: bless, and curse not” (Rom 12:14), “If it be possible, as

much as lies in you, live peacefully with all men” (Rom 12:18), and also

“But the fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, longsuffering,

gentleness, goodness, faith, meekness, temperance” (Gal 5:22, 23).

This teaching on violence is related firmly to the teaching on love.

Violence is rejected because it reflects a position contrary to love.

Those who consider the other as a “thing to destroy” resent the image of

God in him/her. He who wants to eliminate the other from being resembles a

murderer even if he did not actually kill: “Whosoever hates his brother is

a murderer” (1 Jn 3:15), and he who does not accept that the other has an

independent existence but wishes to subdue him/her by force is far from

love, which accepts the other as an other even if he/she did not share the

same gender, color, opinion, or belief, and would not consider him/her a

mere extension of the proud ego, whether this were an individual ego or a

collective ego.

JESUS’ REJECTION TO VIOLENCE IN HIS LIFE:

The rejection of Jesus to violence appears not only in his teaching, but

also in his person and life as well. Indeed in him the prophecy of Isaiah

which he had read in the synagogue, to make clear to the Jews that it

concerns him, was fulfilled: “Behold my servant, whom I have chosen; my

beloved, in whom my soul is well pleased: I will put my spirit upon him,

and he shall show judgment to the Gentiles. He shall not strive, nor cry;

neither shall any man hear his voice in the streets. A bruised reed shall

he not break, and smoking flax shall he not quench” (Matthew 12: 18-20).

The evangelist Luke tells us that one of the Samaritan villages did not

wish to accept him as he made his way to Jerusalem, “And when his

disciples James and John saw this, they said: Lord, do you wish that we

command fire to come down from heaven and consume them as Elias did? But

he turned, and rebuked them, and said: You do not know what manner of

spirit you are of. For the Son of man is not come to destroy men's lives,

but to save them. And they went to another village” (Luke 9:54-56).

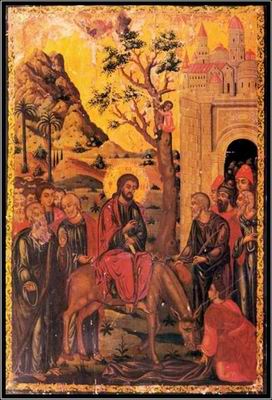

At his festive entrance to Jerusalem before his passion, he refused to

ascend a horse, which was a symbol of war for the Jews, and instead of

appearing as a forceful liberator he took on the appearance of the meek:

“All this was done, that it might be fulfilled which was spoken by the

prophet, saying: Tell the daughter of Sion, Behold, your King comes to

you, meek, and sitting upon an ass, and a colt the foal of an ass”

(Matthew 21:4-5).

And when he was seized he gave his disciples a valuable lesson in

non-violence toward the injustice of the aggressors: “And, behold, one of

them which were with Jesus stretched out his hand, and drew his sword, and

struck a servant of the high priest's, and smote off his ear. Then said

Jesus unto him, Put up again your sword into its place: for all they that

take the sword shall perish with the sword” (Matthew 26:51-52).

While he was questioned before the high priest, the latter asked him about

his disciples and teachings, so Jesus replied with courage that he spoke

openly; then, the evangelist John tells us: “one of the officers which

stood by struck Jesus with the palm of his hand, saying: Do you answer the

high priest so? Jesus answered him: If I have spoken evil, bear witness of

the evil, but if well, why do you smite me?” (John 18:22-23). We should

stop for a moment at this response Jesus gave. Many complain about the

teaching of the Lord, “whosoever shall smite thee on thy right cheek, turn

to him the other also,” emptying these words from their deep spiritual

meaning and holding on to the letter, even though “the letter kills, but

the spirit gives life” (2Cor 3:6), and they see in this teaching an

invitation to submission and cowardice, ignoring the enormous spiritual

energy such an act requires. The behavior of Jesus on this occasion casts

light on the genuine meaning of this commandment. Jesus did not turn his

other cheek and did not show in his reaction any sign of shame, cowardice,

pleasure in receiving pain, or weakness, but he brought the officer to a

halt with an attitude that unites meekness with manhood, splendor, and

honor.

When hatred against Jesus reached its climax and the Master was nailed to

the cross, he faced utmost crime with utmost love, and the peak of

violence with the peak of meekness, crying while on his cross and praying

for his slayers: “Father, forgive them; for they know not what they do”

(Luke 23:34).

Early Christians imitated the meekness of the Master as he had commanded

them: “learn from me; for I am meek and lowly in heart” (Matthew 11:29).

They did not revolt against their oppressors but achieved the greatest

spiritual revolution by offering martyrdom without hatred or grievance.

When the oppressing empire became Christian, many Christians were exposed

to the temptation of earthly power and some were polluted by the spirit of

the world; therefore they oppressed those who did not share their beliefs,

whether pagans or heretics. But the voice of the saints loudly rejected

such practices which contradict the spirit of the Gospel, reminding that

the doctrine of love cannot be defended with weapons of hatred. Let us

listen for example to what St. John Chrysostom said in one of his

homilies: “Altering the mentality of foes is far greater and more

marvelous than killing them; the apostles were only twelve, while the

whole world was filled with wolves. Let us then be ashamed, who do the

contrary, who assault like wolves upon our enemies. For as long as we are

sheep, we conquer, and even though ten thousand wolves lurk around us, we

overcome and prevail. But if we become wolves we are defeated for the

Shepherd will then deprive us of his help, because he feeds sheep not

wolves” (Homily XXXIII on Matthew).

THE MEANING OF MEEKNESS TOWARD THE AGGRESSOR:

It is made clear to us now why Jesus commands us to act meekly even with

those who offend us. That is because the goal is to save the offender. If

we answer his/her violence with violence, how can we save him/her from the

evil that enslaves him/her? In reality, he/she would have won by forcing

us to join him/her in hatred and animosity. But if we face his/her

violence with meekness we may give love a chance to enter his/her heart by

offering a living testimony for true love, unconditional love which

encompasses every human despite his/her faults; even if he/she were

oppressors and haters. Triumphant love is unshaken by the attacks of

violence. This love alone, because it is from God, is able to enlighten

the heart of the human who is chained with hate, to break his/her bonds

and transport him/her from the world of violence to the world of God who

“makes his sun to rise on the evil and on the good, and sends rain on the

just and on the unjust” (Matthew 5:45). That love is alone greater than

hatred and with it we are able to achieve complete and thorough victory.

In that sense the apostle Paul wrote: “Be not overcome by evil, but

overcome evil with good” (Rom 12:21).

Violence bears unending violence, “for all they that take the sword shall

perish with the sword” (Matthew 26:52). But facing violence with meekness

contains the prospect of destroying this hellish spiral, and the ability

to found basis for true peace.

MEEKNESS DOES NOT DENY FORCE:

Meekness is not as tepid as Nietzsche had imagined. It does not deny

force. Force is necessary at times to awaken the rigid consciences. Love

for people requires it sometimes, for he/she who loves his/her brethren

should at times bother and agonize them for their own good, and that is

always done at the expense of the doer’s own comfort. For this reason,

Jesus acted forcefully in many incidents of his life. He was, aside from

being meek, forceful when the situation required force; therefore there is

no similarity between Jesus of the Gospel and the pale emotional depiction

imagined by Renan for instance . He had addressed the Jewish people, and

especially their leaders, in a harsh manner, scolding them over their

pride, hypocrisy, adoration for supernatural acts, and lack of faith: “O

generation of vipers, how can you, being evil, speak good things?”

(Matthew 12:34), “An evil and adulterous generation” (Matthew 12:39), “O

faithless and perverse generation” (Matthew 17:17), and “woe unto you,

scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites!” (Matthew 23:13). His force was clear

not only in his speech but also in deed, as John the evangelist tells us:

“And the Jews' passover was at hand, and Jesus went up to Jerusalem, and

found in the temple those that sold oxen and sheep and doves, and the

changers of money sitting; and when he had made a scourge of small cords,

he drove them all out of the temple, and the sheep, and the oxen; and

poured out the changers' money, and overthrew the tables, and said unto

them that sold doves, Take these things hence; make not my Father's house

a house of merchandise” (John 2:13:16). Even his apostles faced his force,

for he called them “of little faith” (Matthew 8:26), scolded them for

being slow to understand spiritual matters (Matthew 15:16), and rebuked

Peter because he tried to discourage him from sacrificing Himself by

saying: “Get thee behind me, Satan” (Matthew 16:23).

Yet Jesus used force in those conditions without hatred or animosity, and

there was nothing but love in his heart. He embraced with unmatched

tenderness that adulterous people, healing their sick and preaching to

their poor. He called his disciples who were slow to understand and

occupied with earthly things “little children,” and he prayed on his cross

for the Pharisees and Scribes who murdered him, and he wept on Jerusalem

as he called her “killer of prophets,” warning her of punishment. Jesus

used force only as a surgeon uses a knife, not out of hate for the patient

but in his service and for his wellbeing. It is said that some people

apposed the method of non-violence which Gandhi had adopted by quoting

before him the incident where Jesus forced the merchants out of the

Temple, while knowing that the Indian leader was imitating Christ, so he

answered them saying: “If it were possible for you to have the meekness

that was in Jesus when he forced the merchants out of the Temple with a

scourge, I would have allowed you to use scourges.”

MEEKNESS DOES NOT MEAN WEAKNESS:

It is clear then that true meekness does not mean cowardice or

capitulation, but is rather accompanied by persistence to complete the

mission whatever the obstacles may be, even if that led to death. The meek

does not wish to destroy others but does not retreat from sacrificing

himself if the need arises. Jesus the meek was not passive but firm in his

position toward the glorious upon the earth. This is apparent in the

incident told to us by the evangelist Luke: “The same day there came

certain of the Pharisees, saying unto him: Get out, and depart from here,

for Herod will kill you. And he said unto them: Go you, and tell that fox,

Behold, I cast out devils, and I do cures today and tomorrow, and the

third day I shall be perfected. Nevertheless I must walk today, and

tomorrow, and the following day” (Luke 13:31-33). We find that same

determination and resolve - the determination of someone who had given his

life voluntarily for the sake of completing the mission of love which he

took upon himself - in the position of Jesus as he fell into the hands of

his enemies and during his unjust trial, so we see him acting toward his

frightened and nervous enemies and judges as if he were the judge, not as

one to be judged, in meekness accompanied by strong quiet resolve.

MEEKNESS DOES NOT CONTRADICT COMBATING EVIL:

Meekness does not mean compromising with evil; its source is love, and

love must always be equipped to combat every evil, because evil threatens

others in body and soul. Meekness does not mean that a human should stand

inactive before evil. But it does impose a special method of combating

evil. It entails that evil be fought without hatred for the evil person,

to resort to peaceful means whenever possible, and to seek to stop evil by

addressing the minds of people, no matter how devoted they were to serving

the passions, and to their hearts, no matter how corrupted, and to their

consciences, no matter how rigid they have become. It requires faith in

that the image of God is still implanted in the depth of the human being,

even if it had been distorted. Meekness therefore has great patience

(“love endures” says the apostle) because it contains much respect for the

other, even if he/she had gone astray.

Gilbert Cesbron wrote in his latest novel Between Dogs and Wolves :

“Pacifism is not the opposite of violence, but patience is.” Yet this

patience of meekness is the strongest weapon against evil. Meekness fights

the roots of evil because it attempts to extract animosity from the heart

of the aggressor and reclaim him for the camp of love, while fighting evil

with hatred and animosity results in making it everlasting, even if things

became different on the surface. Therefore, since meekness has such

supernatural power in fighting evil, we find the powers of evil revolt

against it with rage, and the unpredictable, at first sight, happens; that

is when the meek who hates no one and preaches that no one else should

hate becomes the victim of hate; the martyrdom of Gandhi, the messenger of

non-violence in our time, is but a deep and effective example of that.

WAYS TO GAIN MEEKNESS:

Meekness is not merely a pleasant emotion or a comfortable and easy

position. It is a resolute and difficult commitment in a world that is

often ruled by the right of might. Cesbron explains in the book mentioned

above: “It is more difficult for one not to be violent while violent

people attack him.” In other words, one must reverse the popular notion

that one must be a wolf among wolves. Meekness requires a renewed look at

the human, the universe, and new criteria in evaluating issues, making

love the definite and ultimate value, because “God is love; and he that

dwells in love dwells in God, and God in him” (1 John 4:16), “for love is

of God; and every one that loves is born of God, and knows God. He that

does not love does not know God; for God is love” (1 John 4: 7-8).

Meekness necessitates a new understanding of action, and a pursuit, not

for superficial and cheap action, but action that is genuine and deep.

It requires liberation form ego-centrism to be able to consider the other

as an objective, not merely a means and a tool. It requires in the end

true conversion and transformation in the depths.

This conversion is a conversion to Christ, because “hereby perceive we the

love of God, because he laid down his life for us” (1 John 3:16). The way

to gain meekness is for the image of the meek Christ to become enacted in

us by humble reading of the Gospel; it is for Christ’s love to live in us

by prayer, the sacraments, and observing the Word. If this love is

established in us we can be free from pride and love for power, the two

main motives for violence. And if fear is one of the sources of violence,

then gaining meekness requires liberation from the yoke of fear, and that

happens when we become certain that we are loved by God, partakers,

although weak, in the victory of the Lord who rises from the dead to

“deliver them who through fear of death were all their lifetime subject to

bondage” (Heb 2:15). Thus we may attain confidence that allows us to

demolish the bonds of our isolation in order for us to embark, in turn, on

the risk of love without fear.

VIOLENCE OF LOVE:

If we walk on this path of meekness, what then will be the fate of the

energy of violence that is concealed in us and which accompanies our life

itself to some degree? The solution of course is not to sever it, thus

weakening a force that was founded to be mobilized entirely in the service

of God. We are not required to suppress it in the Freudian sense either,

that is to ignore it exists, which threatens with breakdown and explosion.

Human instincts are not evil per se, but are confused as is the case with

all the powers of the fallen and wounded human. Therefore it is essential

that they pass through the sacrament of the cross for purification and

restoration. The Lord does not expect us then to suppress or sever the

energy of violence that is in us, but to control it with conscience and

tame, civilize, and consign its power to the direction of good. In other

words, we must “enhance” the energy of violence that is in us to the level

of love; thereby we may direct this enormous energy instead of becoming

enslaved and controlled by it. By doing so we can fight with it a war that

is unlike the wars of mortals, although it is not, as the poet Rimbaud

says, less violent than those are. It is the spiritual war, which contains

no hate, against the evil that is in us and around us; it is zeal over

God’s question on earth, because “The zeal of your house has eaten me up”

(John 2:17).

To this struggle, not to submission and inaction, does Christ call us when

he says: “Do not think that I come to send peace on earth; I came not to

send peace, but a sword” (Matthew 10:34), and “the kingdom of heaven

suffers violence, and the violent take it by force” (Matthew 11:11).

The only violence that is fitting to God and worthy of humans is the

violence of love, that love which knows no rest for it is a glorious

flame: “I have come to send fire on the earth; and how I wish it were

already ablaze” (Luke 12:49).

1963

* This article first appeared on the web in the February 2005 issue of

In Communion. http://www.incommunion.org/2005/02/22/christ-and-violence/ |