|

Religion

in Language Policy, Religious systems exert tremendous influence on shaping language policy, both in the ancient and the modern states of the Fertile Crescent. For two millennia the Syriac language was a symbol of identity among its Christian communities. Religious disputes in the Byzantine era produced not only doctrinal rivalries but also linguistic differences. Throughout the Islamic era, the Syriac language remained the language of the majority despite Arabic hegemony. The decline of Syriac accompanied the decline of Christianity in the East, and was affected by the policies of rival religious and nationalist groups. In the modern era Syriac speaking communities in the Near East were beset by a number of tragic events. Modern nationalist regimes in modern nation states in the Near East restricted the use of Syriac to the church and some parochial schools. By considering the current conditions under which Syriac speakers live, and the renewed interest in reviving the language among Christian communities in the modern Fertile Crescent, this thesis will examine the causes of decline over the centuries, and possibilities for the revival of Syriac in modern times. TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE: SYRIAC AS A LANGUAGE OF FAITH AND IDENTITY CHAPTER TWO: SYRIAC AND THE EASTERN ROMAN WORLD CHAPTER THREE: Syriac in the Shadow of the Caliphate CHAPTER FOUR: Syriac in the Age of Modern Nationalism APPENDIX A: GLOSSARY OF IMPORTANT TERMS CHAPTER ONE SYRIAC As A LANGUAGE OF FAITH AND IDENTITY The ethnic and religious makeup of a society decides in many cases the final shape of its language policies. Although language spread, policy and rights can be studied as separate concepts, my thesis will examine how policy affects demographics and establishes limits on language use within the polity in the case of Syriac. In general, “an explicit language policy is adopted because of the coexistence of several languages in one polity and the necessity of regulating their functions and mutual relationships” (Coulmas, 2005, p. 185). This relationship is affected by power relations among the different ethnic groups as well as the religious attitudes in the target society. The distribution of languages and writing systems is historically related to political, cultural, or ethnic factors. I would argue here that religion plays a major, if not a primary, role as one of these factors. Ferguson (1982) notes that “the distribution of major types of writing systems in the world correlates more closely with the distribution of the world’s major religions” (p. 95). One cannot deny the strong connection between Hebrew and Judaism, Classical Arabic (or the Arabic script) and Islam, Greek and Eastern Orthodoxy, and Latin and Catholicism, to cite a few examples. In Eastern Europe and the Middle East the religious factor in language spread, rights, and policy proves central to any discussion of the historical evolution of language within the state. Language Policies produced by modern nationalist or secularist regimes were in many cases reactions to the religious makeup of the culture and language. Language policy can be defined as the process by which governments regulate languages through legislation, recognition as official in status, and permitting their use in public discourse, education, and religion. Language policy is connected in that sense to language planning, which describes the active process through which a language policy is implemented. Language rights define the amount of freedom allowed to groups to use their language (or languages) within the polity. This is often determined by observing the policies employed by the dominant group to spread and assert its language. The present research examines how religion contributed to the shaping of language policy in the case of Syriac. Our historical examination of the Syriac language under different dominant religious groups will demonstrate how such policies were triggered by religious attitudes. Language spread and distribution is associated in many cases with the spread and distribution of religions and sects that identify with certain languages or certain elements of these languages. The spread of the Islamic empire, for example, made Arabic dominant from Spain to India in the Middle Ages, and where Arabic did not replace the native languages, it replaced the original scripts, as in Persia, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. Turkey, which used the Arabic script for centuries, following the Ottomans’ conversion to Islam, only dropped it in favor of the Latin script after WWI. Christianity in the East provided scripts to many nations from the Baltic to the Balkans. The Armenians and Georgians received scripts from Syriac missionaries, and the Slavs received the Cyrillic (after St Cyril) alphabet, which is based on the Greek alphabet, from Eastern Roman missionaries. The linguistic consequences of religious conversions, the demographic changes in the religious makeup of societies, and the balance of power between various religious groups in any society are factors that cannot be overlooked. Shifts in language are often, if not always, accompanied by religious or ideological changes. Sweeping linguistic “reforms” in modern revolutions aimed for the most part to modify or undo religious attributes of language, which stood in opposition to their secular goals. In France, Russia, China, and Turkey, to name a few examples, revolutionary regimes extensively modified languages, scripts, and vocabulary to filter out religious elements. The efforts of the leaders of these “revolutions” in themselves originated from their own ideological stand on the role of religion in society, education, and human life. Mustafa Kemal Ataturk (1881-1938) of Turkey would follow suit with his massive reforms to modernize Turkey after WWI. To eliminate what he believed to be the backward effects of Islam on Turkish society and education Ataturk dictated many measures in the realm of linguistics, from eradicating the Arabic script from public use and adopting the Latin script to introducing new forms and terms to the Turkish language which distance it from traditional Islamic influences (Tachau, 1964). Drawing on insights from linguistics, notably language spread and policy research, my thesis will focus on the emergence of Syriac out of the Aramaic variety as a language of biblical associations and Christian identification, its role in spreading Christianity and representing it, the impact of policies of rival religious groups on it, and the modern attempts to revive it. Syriac is defined as the Christianized Aramaic (the Aramaic variety also included Jewish Aramaic, which evolved separately). It was favored in the schools of Nisibis and Edessa, and became the lingua franca of the Fertile Crescent by the fourth century. Syriac is unique in being a prestigious language of theology and learning but not of the political elite in territories where it was spoken. The adoption of Syriac as a theological language by Mesopotamian Christians, in the schools Edessa and Nisibis, and the emphasis on Greek for legislation and theology in the communities of Western Asia Minor and Syria created a rift which still exists today. The religious prejudices that followed the Third and Fourth Ecumenical councils gradually divided the Christian community in the Near East between Syriac and Greek, especially in the cities. In the Islamic era, the decline of Syriac was accompanied by the decline of Christianity in the East and the dominance of Islam and Arabic, the language of the Quran. Under Byzantine rule, advocates of Syriac clashed with the advocates of the Greek language, and taught that Aramaic was the sacred language of Christ and Scripture (Barsoum, 2003). This stance played a very important role in identifying the Syriac and Coptic Monophysites who opposed the Fourth Ecumenical Council at Chalcedon in 451 (Meyendorff, 1989), which decreed that Christ had two natures, human and divine. Although Syriac was the language of many pro-Chalcedonians, a social and linguistic schism resulted from that event, and rooting out the other group’s language from the churches was meant to weaken any association with the ideology it represented. Greek slowly replaced Syriac in Chalcedonian churches that identified with the Greek imperial church, while Syriac marked those that defied Constantinople (Hitti, 1961). Arab tribes settled the plains of Syria and Iraq as early as the third century AD, and established two kingdoms which remained mostly semi-independent allies within the Roman (the Ghassanids) and Persian (the Lakhmids or Muntherids) empires (Butcher, 2003). Both of those small Arab kingdoms were also staunch rivals, politically and religiously. The Lakhmids embraced Nestorianism (dominated by Eastern Syriac) and rejected the Third Ecumenical Council of Ephesus in 431, while the Ghassanids embraced Monophysitism (dominated by Western Syriac) and rejected the Fourth Ecumenical Council of Chalcedon in 451. Of course, both beliefs were problematic for Constantinople, which viewed them as heretical and a danger to church and imperial unity. After the Muslim invasion in the seventh century AD both kingdoms were destroyed. The beginning of Arab hegemony was with the rise of Islam in the seventh century, and the occupation of Syria, Palestine, Egypt, and Iraq between 635 and 644 AD. Arabs aimed to unite their empire religiously and linguistically, at least the elite, who, with very few exceptions, could not be Christian. Nevertheless, sizable communities of Syriac speaking Christians survived throughout the Middle East for centuries. Needless to say, under the caliphs of the Arabs and the sultans of the Turks Islamic law guaranteed Christians and Jews limited legislative, religious, and linguistic autonomy within the Islamic state (Kucukcan, 2003). Although these Christians and Jews were regarded as protected dhimmis (protected minorities that paid a special tax called jizya according to Islamic Law), they fared generally well under most rulers for a millennium; this is despite occasional outbursts of state persecution and violence that interrupted that coexistence. With the rise of Arab nationalism in the twentieth century, Arab nationalists viewed Syriac as a language representing a problematic religious and national identity, which threatened the desired hegemony of Islam and Arabic. Likewise, Turkish nationalism regarded Syriac, among other languages, as an obstacle to national unity (Smith/Kocamahhul, 2001). These movements modeled their linguistic policies after nineteenth century European nationalists (Baron, 1992), who enforced language uniformity over what they viewed as national territory (Paulston, 1997). As a result, such Middle Eastern movements, with their ultra-nationalistic views, adopted policies that made it impossible to revive Syriac outside the narrow confines of the church and some elementary parochial schools in Syria, Lebanon and Iraq (O’Mahony, 2004). Studies on the interaction between language and religion have been receiving more and more attention by linguists in recent years. Scholarship on the important effects of religion on language, and on how language, as a carrier of ideas, shapes beliefs, has, until recently, been undervalued and little explored. The religious component of language is usually lumped with other social factors under the obscure term “culture.” A negative attitude prevails in academia toward religion as an element that is weaved into the very fabric of language. Linguist Bernard Spolsky (2003) believes that while a great number of works have addressed the relationship between religion and language there is great need for the study of the role of religion in relation to language contact and language policies. Spolsky says that this “may well have been because many of the scholars interested in language contact were themselves so steeped in secularism that they did not easily become aware of the depth of religious beliefs and life” (p.82). Saville-Troike (2006) examines religion as a macrosocial factor in language designation, which “involves social and political criteria. For instance, religious differences and the use of different writing systems results in Hindi and Urdu being counted as distinct languages in India, although most varieties are mutually intelligible” (p. 12). Similarly, Bosnian and Montenegrin, which had been categorized within former Serbo-Croatian, were officially designated as separate languages. Likewise, Serbo-Croatian is “itself a single language divided into national varieties distinguished by different alphabets because of religious differences” (p. 12). Saville-Troike also stresses the “symbolic function of language for political identification and cohesion” for nation building, and the unifying role language plays in empire building (p. 122). Researchers have identified several factors that determine language survival or revival. Hebrew, a dead language for two millennia, was revived when national, political, religious, and educational factors met to produce a successful outcome (Nahir, 2003). For the purpose of this thesis I would stress the religious aspect as major in comparison to the national or political aspects of this case, since Israel, even before it was named as such or created through immigration of Jews, was described in the Balfour Declaration of 1917 as a homeland for the Jews. The restoration of Hebrew as the language of this religiously ascribed nation is central to the formation and unity of the new state. As is the case with other Middle Eastern countries, the separation between religion and state in this secular entity is artificial once a closer look is given to minority rights to land, political power, joining the army, or the preservation of cultural and historical identity. Paulston (1997) points out that a linguistic minority does not depend on the number of speakers but on the power relations that make one language more privileged than another. The status of Syriac was overshadowed by the dominant languages of the ruling class. In the Byzantine era it was Greek and in the Muslim era Arabic. Syriac was recognized as a language of theology and as a semi-official language in the Byzantine era, but that status was lost in the Arabic era. Dominance, or its lack, of a language depends on political circumstances, social structure, and historical traditions. All these elements ultimately relate to religious factors which to some degree control each of them. The gradual decline of Syriac signaled the loss of culture and power to the invading Arabs. Romaine (2005) surveyed languages in the Balkans and showed how such concepts as ethnicity, nationality, language, and religion interrelate. Religion was the main criterion for deciding national or ethnic groups; Greeks identified with the Greek Orthodox Church and Turks with Muslim schools. Macedonians (Orthodox) and Albanians (Muslim) were merged with these two groups, their ethnic identity was suppressed, and they were not separately recognized. Persecution of linguistic minorities for the sake of national unity is common in both democratic and despotic systems. When a religion that identifies with a certain language is targeted by the state, eliminating the official uses of that language is adopted as a tool to assimilate the group. A close examination of the history of the Arabic conquest of the Fertile Crescent shows the correlation between language and religion in relation to power. When the diwans (government registry) in the Islamic empire were still in Greek (the official language of the Eastern Roman rulers), Syrian and Coptic Christians were allowed a greater share of power in the state because of their knowledge of state affairs and the Greek language. Once the diwans were translated under The Umayyad Caliphs Abd Al-Malik Ibn Marwan (685-705 AD) and Al-Walid Ibn Abd Al-Malik (705-715 AD), Christians lost their jobs in all government offices, and whatever civil rights they enjoyed suffered as a result. This event is in fact most crucial as a first step to Arabization and Islamization of the conquered regions of the Fertile Crescent. While several scholars have contributed to the discussion of the role of religion in language policy and planning recently, little work on Syriac or other minority languages in the Near East has been the focus of a serious study from a language policy perspective. The present study takes into account the nature of language outside the secular societies of the West. It primarily aims to emphasize the religious component of language policy in a non-western environment, and it examines how religious factors affect the development, spread, or decline of a language.

Chapter TWOSyriac and the Eastern Roman World

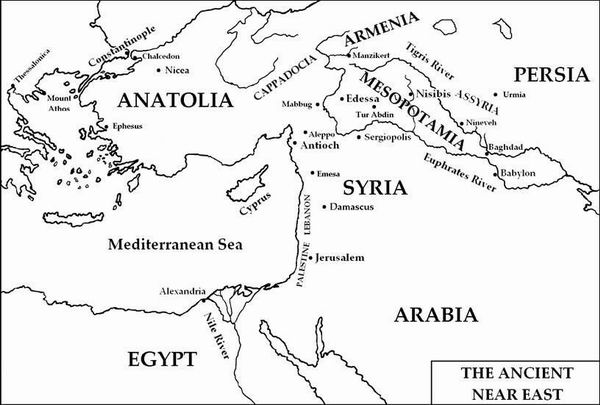

Many Syriac authors refer to Syriac and Aramaic interchangeably, but modern scholars try to distinguish the two by regarding Syriac as a branch belonging to a larger family of Aramaic dialects. Old Aramaic had served as the official language of successive empires that ruled the Fertile Crescent and beyond for many centuries before Christianity. Jewish Aramaic evolved separately out of the old Aramaic as a result of the exile of Jews to Babylon in the sixth century BC (Sokoloff, 2001). Hebrew still uses the old Aramaic script, which is referred to as Square Hebrew (Gaur, 2001). The various Aramaic dialects that developed may differ in script and speech to a degree that sometimes impedes mutual comprehension among their speakers. The origin of the name “Syriac” is a source of debate among scholars and the various national groups that speak it. The term “Syrian” first appears in Greek works, and it was used to describe anyone who spoke Aramaic. The Greek historian Herodotus (490-425 BC) applies the term to the entire Fertile Crescent, including Cappadocia in Asia Minor. According to Herodotus, the term “Syria” was used by the Greeks, while the term “Assyria” was used by non-Greeks. One should keep in mind that the work of Herodotus is the only reference we have to the period before Alexander the Great. The classifications that appear in later works correspond to the political division of the Fertile Crescent territory after the death of Alexander. In the Greek Septuagint translation of the Old Testament (third century BC) “Syrian” is used to describe Abraham (Deuteronomy 26:5), but the older Hebrew text uses the term “Aramaen” instead. The Septuagint translates “Aram” as “Syria” and “Aram-Naharaim” (literally “Aram of the rivers”) as “Mesopotamia.” In the Roman era “Syrus” was anyone who spoke the Syriac language (Hitti, 1951). Ptolemy (90-168 AD) differentiated in his work The Geography between Syria and the areas east of the Euphrates, which included Mesopotamia to the north and Babylonia to the south. Philostratus (early third century AD) considered the inhabitants of Antioch “Assyrian,” and the geographer Strabo (early second century AD) associated the Neo-Assyrian Empire with the Syrians, but he reminded his readers that the term Syria may be used to describe a specific region, i.e. Roman Syria, or in a more general sense, it may include Cappadocia and Mesopotamia as well (Butcher, 2003). The Greek church historian Eusebius of Emesa (300-360 AD) speaks of ancient documents in Edessa, east of the Euphrates, which he researched to write his Ecclesiastical History, and those were written according to him in the “language of the Suroi” (Miller, 1993, p. 463). Frye (1992) examines the use of these two terms in the chronicles of Michael the Syrian, the Jacobite patriarch of Antioch (1166-1199 AD), who “wrote that the inhabitants of the land to the west of the Euphrates River were properly called Syrians, and by analogy, all those who speak the same language, which he calls Aramaic, both east and west of the Euphrates to the borders of Persia, are called Syrians” (p. 283). While some scholars consider “Syria” synonymous to “Assyria,” others like Hitti (1951), Miller (1993), and Joseph (1997) disagree and regard it as a confusion of historical facts. Joseph (1997) argues that “Aram (Syria), and geographical Assyria were two different geographical, ethnic, and cultural entities” (p. 38). Setting the Greek terminology aside, Rollinger (2006) presents evidence from a Phoenician inscription near Adana in Turkey to prove the derivation of “Syria” from “Assyria.” While scholarly sources seem undecided on this issue, I would suggest that the Syriac language, shared by peoples on both sides of the Euphrates in the Christian era, presented itself as a symbol of religious and national cohesion. Syriac was the language of the small Christian kingdom of Osrohene, whose capital was Edessa. As a Christianized form of Aramaic, Syriac rejected the pagan associations of old Aramaic but remained loyal to its legacy, which predates the Christian faith and links its speakers to the literature of the Old Testament. In the opening of his very important book on the history of Syriac, Barsoum (2003) writes: “The Aramaic (Syriac) language is one of the Semitic tongues in which parts of the Holy Bible, such as the prophecy of Daniel and the Gospel according to St. Matthew, were revealed. Some scholars consider it the most ancient of the languages of the world” (p. 3). One must bear in mind that Aramaic had become the language of Judaism after the sixth century BC, and that from that environment Christianity first branched out; Aramaic Christians inherited from Judaism certain traditions about language that were unique to them. Linking language to biblical origins and glorious ancient empires was a source of national identity and pride that could not be abandoned despite the rejection of the language’s pagan past. Syriac speakers’ claims to having one unique, original, and divine language are closer to those of the Hebrews than they are to those of Greek and Latin Christians. This claim to linguistic authenticity was an important reason to resist the domination of Greek. Jewish tradition views Hebrew as the original language that God had authored. Hebrew is viewed as a language of divine origins and unique power in the Midrash (Genesis Rabba 2:1), “since it had preceded creation and been its blue-print” (Weitzman, 2001, p. 71). In a similar approach, Syriac was viewed by the Mesopotamians and Syrians as a language of unique divine origins. This was due precisely to the great influence of Judaism on Syriac Christianity, an influence that was weaker in Latin and Greek Christian circles. By citing the testimonies of two great eastern fathers, Basil the Great and Ephraim the Syrian, the Syriac bishop and scholar Bar Hebraeus (1226-1286) shows why many in his days believed that Syriac was the first language which existed before the division of tongues at Babel. He finds support for this in the Aramaic word Bhaulbalah (confusion), from which the word Babel was derived following the confusion of tongues that occurred there according to the biblical account. Other Christian theologians thought Hebrew was the original language, an interpretation inherited directly from Jewish tradition. Bar Hebraeus’ discussion on whether Hebrew or Syriac was the pre-Babel language probably mirrors a real debate in his time about which language was actually the “original.” Despite the fact that Syriac was the lingua franca of the Fertile Crescent, it is important to stress that the region was multilingual, and that bilingualism was not uncommon (Butcher, 2003). Latin and Greek were languages that were used extensively alongside the different Aramaic vernaculars west of the Euphrates, and Persian was the official language east of the Euphrates, where the Hellenic influences introduced by Alexander the Great and his successors had ceased. Greek was strongest in cities and colonies founded by Alexander and his successor Antiochus west of the Euphrates, but despite its status as a language of administration and liturgy in urban churches, it remained a minority foreign tongue in a sea of Syriac (Vassiliev, 1952). Latin, which had been the official language of Syria after the Roman conquest in 63 BC, would die out by the time of Justinian (527-565 AD), and the latter’s laws and edicts, issued in Latin, would have to be translated into Greek so they could be understood by the people in the eastern provinces (Williams, 1904). Translation of such works, especially works related to legislation, into Syriac were commonly made for use in Syriac speaking communities under Roman rule. The first major work to appear in Syriac was the Book of the Laws of Countries, by Bardesan of Edessa (154-222 AD). Even though Bardesan’s teachings were colored by Gnosticism, the work is clearly Christian in nature and provides good information about the social changes that occurred with the rise of Christianity east of the Euphrates (Miller, 1993). The other major work to mention here is the Syrian-Roman Lawbook, which was published in the early sixth century, before the age of Justinian. This work is a translation of a Greek original that was probably issued at the end of the fifth century. This translation proves, according to Vassiliev (1952), that Syriac was a dominant language throughout the Roman east, and that Greek was only a language of an urban minority. According to Barsoum (2003), Syriac speaking converts to Christianity destroyed all ancient pagan texts written in Aramaic. The earliest Syriac inscriptions from the area of Edessa date back to 6 AD (Healey, 2000), but none of the early pagan inscriptions discovered amount to a coherent piece of literature. Therefore, such few “surviving sources are too insignificant to be taken as a basis for evaluating pre-Christian Syriac literature” (p. 6). The Syriac literature available to us today is purely Christian in nature. This language, which became associated with Edessa, was to become the dominant form used in Christian Syria and Mesopotamia by the fifth century AD. It was also becoming a very important language for liturgical and theological uses, especially since great and important church figures like Aphrahat (270-345 AD) and Saint Ephraim (306-373 AD) spoke and wrote only in that language, adding thus to a body of works that dominated schools and literature in the Fertile Crescent. Meyendorff (1989) writes that “the bishops of the great imperial city of Antioch were all Greek-speaking, but Syriac was spoken by the majority of the population. There existed a strong tradition of Christian learning, which owed nothing to the Greek or Latin West, but which stood in the direct tradition of the Jewish synagogal schools” (p. 98). Religious schisms that occurred during the third and fourth ecumenical councils resulted in a threefold split. Basically, the Third Ecumenical Council (431 AD) resulted in the excommunication of the Nestorians. Although Antioch was the center of the dispute, Nestorians found a safe haven east of the Euphrates where they prospered far from Eastern Roman reach. The Nestorians believed in two distinct natures in Christ (divine and human), while the other camp, led by Cyril of Alexandria, argued for one nature only (in reality they were arguing for one person). The Fourth Ecumenical Council in Chalcedon (451) witnessed the reemergence of the debate, but this time it was between those who argued for one nature alone in Christ (Monophysites) and those who believed in two natures united in one person in harmony (Chalcedonian Orthodox). The Monophysite doctrine spread in areas under Eastern Roman control and was not necessarily associated with Syriac in the beginning. Roman emperors before Justinian were divided on the issue and avoided any clear-cut solutions that might inflate the problem. Nevertheless, the activity of Syriac missionaries in areas far from Constantinople and the conversion of the Ghassanid Arabs to this belief, promising to support and spread it at a time when relations with Constantinople were sour, made matters worse. The Ghassanid king Al-Harith embraced the Monophysite bishop and missionary Jacob Bar'Addai and became a staunch opponent of Chalcedon (Meyendorff, 1989). The Ghassanids thus stood in opposition to Constantinople’s uncompromising Chalcedonian stand under emperor Justinian and his successors. The council of Chalcedon, which Constantinople had engineered and Rome had endorsed, came together in 451 to resolve the issues that led to the schism in Ephesus in 431. The formula introduced by Constantinople and Rome was regarded as a compromise by both the radical followers of Cyril of Alexandria and the Nestorians. Attempts to restore unity continued for decades, but were further hampered by the advance of the Persians into Syria proper and the great persecutions that Christians had to endure under them, even though “there is evidence that Justinian, having re-established a peace with Persia in 561, obtained stipulations protecting the rights of Christians” in the hope of reuniting the Nestorians with the Orthodox (Meyendorff, 1989, p. 288). The Persians had little to fear from a sect rejected by their Roman enemy, and for that reason Nestorians were allowed some freedom after the schism. In turn, the Nestorians had little interest in restoring unity with Constantinople, which would make them appear loyal or subject to the enemies of their rulers. Association with the imperial church of Constantinople would have had drastic ramifications if followed through. The Nestorian church was thus able to survive under Persian rule east of the Euphrates, and due to political constraints and ideological differences it evolved on its own. This break led with time to increasing differences between eastern and western Syriac speakers, both in language and script. By the sixth century most Syriac speakers were divided between the Nestorian church (referred to as Assyrian), and the Monophysite church (the Syrian Orthodox or Jacobites). These two groups represented two radically opposing views in Christian theology. In the sixth century the Syrian Orthodox theologian Philoxenus, bishop of Mabbug in northern Syria, revised the Syriac translation of the Bible (i.e. the Peshitta) and aligned it with the Greek original because he found certain passages to be susceptible to a “Nestorian” interpretation (Brock, 1980). Some scholars blame linguistic differences between Greek and Syriac for the schism in Chalcedon (Abouna, 1992), but this argument does not hold water because “almost all the spokesmen of the opposition [to Chalcedon] were Greeks deeply loyal to the Empire” (Meyendorff, 1989, p. 252). The same can be said of the Nestorian belief in two separate natures in Christ, which began with Nestorius (386-451 AD), a patriarch of Constantinople and a Greek speaking hierarch. It is possible, however, that the Monophysites understood “nature” to mean “person” or “hypostasis,” and having “two natures” in Christ meant being two separate persons for them, a definition which agreed in their opinion with the concept produced by Nestorius. While cultural, national and ethnic factors contributed greatly to the schism, the most direct reason remains doctrinal. Syriac, as well as Coptic, became exclusive languages for Monophysite theologians in a reaction to Greek becoming the official symbol of Chalcedonian dogma and imperial repression, but this process of segregation took years to complete. The Monophysites recognized the “Greek” church of Constantinople and its followers as “Roman.” Syrian followers of Chalcedon were given the pejorative label “Melkites” which means “Royalists” (Hitti, 1951). The Orthodox Chalcedonian church embraced Greek terminology to express its theology. The Greek language was an important language in theology and liturgical use in the cities of Syria and Asia Minor. Greek had been in use in the region since the days of Alexander the Great, as we mentioned above, and was applied primarily by the aristocracy and intellectuals in the Greek colonies of western Syria. Nevertheless, Syriac remained the language of the majority of the population, and this was especially true eastward. In the sixth century Greek replaced Latin as the official language, as Mango (1980) explains: “following the eclipse of Latin, Greek became the only official language of the Empire, so that a knowledge of it was mandatory for pursuing a career or transacting business” (p. 27). Because the Syriac language was that of two major heretical groups, the Nestorians and the Jacobites, one of which was protected by an enemy state, the Orthodox Christians who confessed the faith of Constantinople had reservations about the use of Syriac in teaching and missionary work. In other words, in ecclesiastical circles Greek came to represent correct doctrine. Emperor Phocas (602–610 AD) ended all hope of unity between the Orthodox and Syrian Jacobites when he began a bloody suppression of the latter group. The emperor also provoked a Persian invasion which devastated Syria and almost caused the collapse of the entire empire. The beginning of religious nationalism in Syriac communities may be traced back to this period. Monophysitism becomes synonymous with Syrians and confined to a certain national group. We read in Meyendorff (1989): The great majority of Syriac-speaking monasteries and villages were faithful to Monophysitism. It is then, on the eve of the Persian invasion, and following the activities of Jacob Bar'Addai, that confessional loyalties became interwoven with ethnicity: words such as "Syrian" and "Egyptian" turned into normal designations for opponents of Chalcedon, whereas the term "Greek," more often than not, became synonymous with "Melkite" (the "emperor's man") and reflected Chalcedonian loyalty (p. 270). Some of the early signs of Syriac and Greek being identified as theologically opposing can be seen in the sixth century. Even though John of Ephesus, a sixth century Monophysite bishop, was versed in Greek, he chose to write entirely in Syriac (Treadgold, 1997). Other Syriac speaking church figures rejected using the language of the Chalcedonians as well. In the Pseudo-Amphilochius Life of Saint Basil, a hagiographical account of the life of the saint, the author presents an account of a meeting between the greatest Syriac speaking figure, Saint Ephraim the Syrian, and Saint Basil the Great, one of the important Greek fathers of Cappadocia. In that encounter Basil ordains Ephraim to the deaconate and Ephraim miraculously receives the “most divine gift” of speaking Greek (Taylor, 1998). The devotion and respect held for Ephraim by the Greek speaking church cannot be underestimated, but the account in this hagiography aims to distance the saint from any suspicion of heresy, which by the sixth century had contaminated the Greeks’ opinion of most Syrians. The association of Ephraim with the Greek fathers and the formal language of the Orthodox Church presented a Hellenic Ephraim that was easily accepted by the Greeks. The Pseudo-Amphilochian account, while exalting the saint, degrades the Syriac language as somehow insufficient for theology and subordinates the most important figure in Syriac tradition to the patronage of the Greek tradition of Constantinople. Cultivation of the Syriac language in theology, science, and literature required the translation of many Greek works. Syriac took in a large number of Greek words as a result of this elongated and laborious process. Greek also influenced syntax and style in Syriac (Brock, 2001). On the other hand, the influence of Syriac on Greek can be seen in forms of poetry and hymnology that were produced by Greek speaking Syrian writers. One of the most central and most celebrated figures to write poetry and introduce meter in the Syriac church was Saint Ephraim the Syrian. His works had been translated into Greek soon after his repose, and they remain widely read in monastic communities worldwide until this day. Russell (2005) suggests that the traditions introduced by Ephraim can be traced further east to the city of Nisibis rather than Edessa, since that was the city where Ephraim lived and taught for six decades of his life before the Persian takeover. Early Greek hagiography focuses more on Edessa because it was within Roman borders, and was famed for its letter from Jesus Christ to Abgar, ruler of Edessa, which is most likely a legendary apocryphal work made famous by Eusebius and later historians. The influence of Ephraim is clear in the sixth century work of Romanos the Melodist (Carpenter, 1932; Petersen, 1985). Successive church hymnologists in the Hellenized west either relied on, or borrowed extensively from, Ephraim (Palmer, 1998). In later centuries, the works of Ephraim would be among the earliest texts translated into Christian Arabic by the Orthodox “Melkite” monks who lived under Islam after the loss of Syria to the Arabs (Griffith, 1998). Greek speaking Syrians like Andrew of Crete, John of Damascus, and Kozma the Meldodist contributed to the formation of Byzantine hymnology (Yazigi, 2006). These exchanges and interactions between the Greek and Syriac traditions produced a unique Eastern tradition that combined Hellenic and Aramaic elements. Despite all these developments, Syriac continued to be used by Chalcedonian rural communities in Syria until the end of the Middle Ages. The tenth century bilingual inscriptions discovered in northern Syria’s most important ecclesiastical construction, the monastery of Saint Symeon the Stylite, show Greek and Syriac texts together (Obermann, 1946), and elements of Syriac and Greek traditions harmonized in Byzantine Syriac architecture in what is now called the “Dead Cities” of northern Syria (Pena, 1997). To the East, in the city of Sergiopolis in the Syrian Desert, the columns’ inscriptions found in the sixth century main cathedral used reversed Greek, written from right to left like Syriac (Fowden, 1999). This unusual practice is perhaps a consequence of the schism, and is most likely meant to show Monophysite opposition to “Greek” Orthodoxy. There are two main dialects of Syriac that seem to correspond to the natural and political geography of the Fertile Crescent. The Western dialect covers areas west of the Euphrates River, while the Eastern covers the areas east of it (refer to Appendix B for a map of the ancient Near East). Another way to view this divide is by considering the fifth century border between the Roman and Persian empires. Prior to that date speakers of Western Syriac all lived under Eastern Roman rule, while speakers of Eastern Syriac lived under Persian rule. Both views are valid, but using the religious component of this division can lead one to a stronger argument. Referring back to Barsoum (2003) we read: At the beginning of the sixth century A.D., Syriac was divided according to its pronunciation and script into two dialects, known as the Western and the Eastern "traditions". Each of these traditions was attributed to the homeland of the people who spoke it, i.e., Western for those who inhabited al-Sham [Syria] and Eastern for those living in Mesopotamia, Iraq and Azerbayjan. However, the Syrian Orthodox community in Iraq is excluded from the Eastern part (pp. 4-5). Excluding the Syrian Orthodox (Monophysites) from the Eastern part, even though they geographically exist in it, brings us back to a religious explanation for the causes of this split. That in turn will lead us to a discussion of the religious distribution of Christian sects in the fifth century, mainly the aftermath of the third and fourth ecumenical councils. Linguistic ramifications accompanied the schisms that resulted from these councils. It would not be an exaggeration to suggest that each religious camp identified with, and monopolized, a certain language or dialect, which was exclusive to its own religious identity and expression of the faith. That language (or dialect) marked the group. However, I would not exclude non-religious factors as contributors to the linguistic changes of the time. I only present religion here as a major, and not an exclusive, component. The political and religious distance between the Assyrians and Syrians that began in the fifth century contributed to a shift from the vowel [α] to [ο], which became common in the west. The more archaic [α] was preserved only within the Church of the East (Brock, 2001). Later centuries witnessed increasing differences in the vocalization systems of the two dialects. It should be noted that a great number of local dialects exist in Syriac depending on the geographical area, but in writing only two distinct forms are applied, the Jacobite and the Nestorian. Written (or ktobonoyo) Syriac is almost identical in form to the early fourth century Syriac texts. There are two main types of script applied in Syriac: the Estrangela (from Greek strongulos, “rounded”), which was used in the east, and the Serta, which was a cursive script used by the Syrian Orthodox and Maronites in the west. The earliest inscriptions that date back to the first and second centuries resemble the estrangela script. Therefore, many scholars consider the Estrangela to be the older form used to write Syriac (Brock, 1980), but newer studies contest this view and claim that the Serta is only a cursive informal style of writing of the formal Estrangela. The earliest Syriac had “a formal script rather similar to what is later known as estrangela. It was used for formal monumental purposes, inscriptions on stone. The other script was a cursive which was used for less formal everyday purposes” (Healey, 2000, p. 63). The cursive Serta can thus be considered a modernized form of the old formal Syriac script that came to be called Estrangela. The most recent development of Syriac script is the appearance of a unique script based on the Estrangela in the East, and it is often referred to as “Nestorian” or “Chaldean” (Brock, 1980). In the seventh century attempts to create a vowel system for Syriac resulted in two different systems east and west. The western system applied by the Syrian Orthodox and Maronites used a vowel system derived from Greek letters, but to the east the Assyrians applied different combinations of dots instead. The former system of vowels is called the “Jacobite” while the latter is called “Nestorian” (refer to Appendix C to view the different consonant and vowel types). Syriac inscriptions were discovered in many locations outside its land of origin. In India the Syriac language is still used as a liturgical language by millions of followers of the Syrian Orthodox Church there, and according to Encyclopedia Britannica (2000) there is archeological evidence of Syriac being used in China, central Asia and Siberia until the thirteenth or fourteenth century AD. This was primarily due to the fervent activity of Nestorian missionaries in Asia during the Middle Ages. Literacy and education are major factors in language spread (Ferguson, 1982), and both are important to formulate and manage language policy in any state. Syriac developed effective tools for spreading literacy; its practical script and application to texts of a growing faith, coupled with its inheritance of the already established Aramaic tradition, made it a popular medium for teaching throughout the Near East. Since literacy had been so central to spreading Christianity, Syriac was applied effectively to produce a cohesive religious community, which had a unified religion and culture. Educational policy in the Eastern Roman empire, beginning with Justinian, was gearing towards a “Greek” Orthodox system of education. In the first decades of his reign, Justinian targeted the remaining centers of pagan education, closed the school of Athens, and ordered Jews to use the Greek text of the Bible in their synagogues instead of the Hebrew text. In essence, “since Justinian intended to enforce correct belief within the empire, which in turn rested on correct interpretation of sacred texts, biblical exegesis and Christian education fell directly into the imperial sphere” (Maas, 2003, p. 75). Syriac schools on the other hand suffered from the Persian invasion and imperial suspicion of heresy in Eastern Roman territories. The school of Nisibis, which Saint Ephraim had abandoned on the eve of the Persian takeover in 363 AD, was reopened in 471 AD, and became a Nestorian stronghold that spread Nestorianism eastward as far as China and India. The school of Edessa to the west remained active between 363 and 457, and “carried a tremendous potential for cross-fertilization between the Greek and Syrian worlds” (Meyendorff, 1989, p. 98). However, the school was drawn into the christological controversies of the time and rejected the terminology produced by Greek theology, notably that of Chalcedon, which left its students and teachers polarized between Nestorianism and Monophysitism. The school was ultimately closed by emperor Zeno in 489 AD. Nisibis and Edessa were the most important centers for Syriac education, but their deviation from the ideological standards of the “Greek” Orthodox Church made any work of theology written in Syriac suspect in the eyes of Chalcedonian Christians. The linguistic segregation that followed the schisms and the increasing imperial support for Greek as a language of “true” doctrine would also affect Latin speakers in Europe. After Justinian, “when knowledge of Latin became rare at the imperial court in Constantinople, the Greek-speaking world closed itself off from western thought” (Herrin, 1989, p. 10). Europe would later find its way back to Greco-Roman traditions and sciences through Syriac works or Arabic works translated from Syriac and Greek in the Middle Ages.

Chapter THREE Syriac in the Shadow of the Caliphate

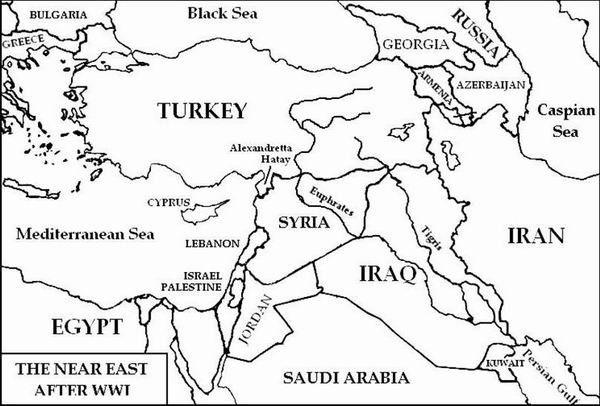

In chapter two, we have seen how imperial unity in the Eastern Roman empire depended on unity of religion, and for two centuries the emperors strove unsuccessfully to unite all branches of Christianity in the empire under the dogmatic formula produced in Chalcedon. The last attempt to reunite the churches before the Muslim invasion was the introduction of the Monothelite (one will) formula by emperor Heraclius (611-641). This attempt caused another group to break off from the Syriac community that supported Constantinople. This group, which united around the monastery of Saint Maron near modern Hama in Syria, supported this doctrine and became known as Maronites. They were soon forced to take refuge in the rugged mountains of Lebanon after the Muslim invasion. Following the death of Muhammad in 632, Muslim leaders elected Abu Bakr (632-634) to be his successor (or caliph). This first caliph was faced with the task of forcing rebelling Arabian tribes back into Islam in accordance with Muhammad’s wishes. These wars were called the Redda wars and lasted until 633 (Conrad, 1994). On his deathbed, Abu Bakr selected Umar Ibn Al-Khattab to be his successor (634-644), and Umar began to send troops to neighboring territories. In 636 his armies defeated the Persians in Mesopotamia and invaded Palestine and Syria in 637. After the defeat of the Eastern Roman army with their Ghassanid allies near the Yarmouk River in 636, the Muslims gradually seized the major cities in Syria. Jabla ben Al-Ayham, the last Ghassanid king, refused to convert to Islam and fled to Constantinople with many of his subjects (Rustum, 1960). The Umayyad caliphs moved the center of the new empire from Arabia to Syria. Their first caliph Muawiya (661- 680) declared Damascus the capital of the caliphate, and fashioned his new empire after the Eastern Roman model, making succession to the caliphate hereditary. The Umayyad caliphate inherited an already established bureaucracy, equipped with many educated and capable natives. Under the new Muslims rule, local Christians still made up the majority of the population and held the most important positions in the administration. Muawiya made Sarjoun ben Mansour, the grandfather of Saint John of Damascus, the minister of finance. Sarjoun served three caliphs: Muawiya (661-680), Yazid (680-683), and Muawiya II (683-685). During this period Syriac was still the language of the populace, Greek was still the official language of the state, and Sassanid and Eastern Roman currency continued to be used in Iraq and Syria. When Muawiya attempted to issue Arabic coinage without the cross depicted on them in 661, the people refused to deal with it. For years, the cross was drawn on official documents, and the caliph's seal was added next to it afterwards (Athanasiu, 1997). Following two failing attempts by Muawiya to invade Constantinople Muslims agreed to pay tribute and protect the remaining Christians and their properties in the conquered regions. The Monophysite Arab Ghassanids stood to lose the most from the Muslim Arab invasion, which brought destruction to their kingdom. The Chalcedonians in Syria were accused by their religious rivals of spying for the Roman emperors, and suffered immensely as a result. The Umayyads thus denied residency to the Chalcedonian patriarchs of Jerusalem, Antioch, and Alexandria. It is likely that the patriarchs returned to Antioch in the time of patriarch George II (690-695) or Alexanderos II (695-702). Albeit, the latter was killed during the reign of Al-Walid, leaving the See of Antioch vacant for the following forty years (Rustum, 1960). Schick (1988) suggests that the succession of patriarchs broke off in Jerusalem as a “consequence of the theological dispute over Monothelitism that was racking the Byzantine Empire and not Umayyad policy” (p. 239). However, such a statement can easily be refuted by the overwhelming testimony of numerous primary sources presented by Hoyland (1997). The patriarchs of the Jacobites were also forced to reside away from Antioch, in Diyar Bakr and Malatia. It is useful to note here that after the rise of emperor Leo III (717-741) and his Iconoclastic movement which advocated the destruction of church icons, Syrian Chalcedonians stood against the religious establishment in Constantinople until Iconoclasm had died out a century later. In the first decades following the Islamic invasion, Arabic had an insignificant impact on the established languages in the regions conquered. In other words, Syriac continued to be the dominant language in Syria and Mesopotamia. Meanwhile, classical Arabic was becoming standardized, and the main reason for uniting the many Arabic dialects by adopting the Quraish dialect as an official language was religious. Al Wer (1997) describes this period as such: During the early stages of the expansion of Islam (the 7th and 8th centuries), the Arabic dialect of Quraysh, the medium of the Koran, came into contact with and was influenced by Greek, Latin, Aramaic and Berber. The language of this conquering minority, whose societies lacked developed social organizations, did not have the necessary terminology to cope with these more sophisticated civilisations. In the newly conquered lands, Arabic failed to make an impact for quite some time and was probably subject to dissipation (p. 252). Disputes over the Quranic text, which raged in the early days of Islam, were settled at the time of the third caliph Uthman (580-656). Standardizing the Arabic language would not be completed until a Persian convert to Islam named Sibawayh (d. 793) established Arabic grammar and explained how the language worked; this was done mainly to teach non-Arab converts the language (Hourani, 1991). In addition to some poetry, the Quran was the only work in Arabic to survive from that period. Transition to Arabic and active Islamization in the caliphate began with the Umayyad caliph Abd Al-Malik (646-705), who replaced Roman currency with Arabic currency in 692. He also ordered the translation of the registry, or diwans, from Greek into Arabic. When Sarjoun ben Mansour refused to do so the caliph replaced him with Sulayman Ibn Sa’ad who became the first Muslim to manage the registry (Rustum, 1960). The caliph thus emphasized Islamic and Arab hegemony in administration, which until then was controlled by Christians. When Al-Walid (705-715) came to the caliphate he completed the transition from Greek to Arabic and dismissed Christians from government positions. Al-Walid’s forceful takeover of the great Chalcedonian cathedral of Saint John the Baptist in Damascus was symbolic of his program to Islamicize and Arabize the country. Arabs called Chalcedonian Christians Rūm, precisely because of their association with the Eastern Romans. Emperor Leo III, who defeated a massive invading Arab army led by the caliph Sulayman (715-717), was himself a Syrian of Arab stock, and knew Arabic as well as Greek (Treadgold, 1997). The Armenian history of Ghevond, written at the end of the eighth century, assigns to Leo one of the earliest Arabic apologetic letters sent to Umar II to refute Islamic teachings (Jeffery, 1944). The official status that Arabic had received after Al-Walid affected legislation and administration directly. Succeeding caliphs varied in their attitudes toward making conversion to Islam a prerequisite for working for the state. With Umar II (717-720) legislation was introduced to strip Christians and Jews of their civil rights through enforcing what was known as the “edict of Umar.” However, during the reign of Hisham Ibn Abd Al-Malik (724-743) these restrictions were abandoned (Hitti, 1961). By and large, religious communities in the caliphate were segregated, and non-Muslims were normally permitted to use their own languages, cultural traditions, and religious practices. This allowed Christian communities to maintain Syriac as a vernacular and liturgical language alongside Arabic, which did not completely dominate the Christian landscape until the end of the Middle Ages. Jacobites and Nestorians continued to use Syriac as a literary language until the thirteenth century (Brock, 2001), but the liturgical use of Syriac in these churches continues to this day. The Rūm, at least in cities and monastic centers of Palestine, seem to have pioneered the adoption of Arabic as a literary and liturgical language. However, there is sufficient evidence that Syriac remained in use in southern Syria and Lebanon until the seventeenth century. Al Wer (1997) remarks that there is no evidence that the “standardised literary Arabic had reached the [non-Arab] masses, especially since access to education and written material was restricted” (p. 253). The Abbasid dynasty came to power with Abu Al-Abbas Al-Saffah in 749 and moved the capital to Baghdad. This transition of power from Damascus to Baghdad raised the status of the Nestorians who had a huge following in Iraq and Persia. In the new capital an active movement to translate ancient works from Syriac, Greek, and Persian into Arabic lasted throughout the ninth century. In 832 the caliph Al-Ma’mun (813-833) founded Bait Al-Hikma, or “House of Wisdom,” which functioned as an academy, library, and translation bureau (Hitti, 1961), and was occupied by Syriac translators and scholars. Among the most renowned of the Syriac translators and authors were the physician and translator Hunain Ibn Ishaq (809-877), Thabit Ibn Qurrah (d. 902), and Kusta Ibn Luka (d. 922) (Fakhouri, 1951). Albert Hourani (1991) writes: The coming of Islam improved the position of the Nestorian and Monophysite Churches, by removing the disabilities from which they had suffered under Byzantine rule. The Nestorian Patriarch was an important personality in Baghdad of the 'Abbasid caliphs and the Church of which he was the head extended eastwards into inner Asia and as far as China. As Islam developed, it did so in a largely Christian environment, and Christian scholars played an important part in the transmission of Greek scientific and philosophical thought into Arabic. The languages which the Christians had previously spoken and written continued to be used (Greek, Syriac and Coptic in the east, Latin in Andalus) and some of the monasteries were important centers of thought and scholarship: Dayr Za`faran in southern Anatolia, Mar Mattai in northern Iraq, and Wadi Natrun in the western desert of Egypt (p. 187). In city churches Christians adopted Arabic for use in liturgical services and polemical writings very early on. An early eighth century dual-language fragment of Psalm 78:20-61 in Greek and Arabic was discovered in the beginning of the twentieth century in the archives of the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, which was the main cathedral for the Rūm before Al-Walid’s reign. The most important feature of that piece is that the Arabic text is written using Greek script (Griffith, 1997). Furthermore, numerous early Arabic documents ensuring protection for Christians, such as the letter from Muhammad to the monks of Saint George Alhumayrah monastery in Syria (Aboud, 2004), probably date back to the eighth century, and belong to a genre of documents purporting to be a guarantee of safety and freedom of worship from a major early Islamic authority. Other fabricated accounts in Arabic and Syriac, like the Life of Gabriel, belong “to the genre of documents which sought to delineate the ideal Muslim-Christian treaty and endow it with authority by attributing it to famous Muslim figures” (Hoyland, 1997, pp. 123-124). This is not to say of course that genuine treaties and guarantees of protection were never issued by the caliphs to their Christian subjects. In Baghdad for example, a pact of protection issued to the Nestorians in 1138 (Mingana, 1926) testifies to their influence during the Abbasid dynasty. Saint John of Damascus, who abandoned the Umayyad court to become a monk in Palestine in the first half of the eighth century, wrote entirely in Greek, although he probably knew Syriac and Arabic, especially since he had worked in the government until conversion became obligatory. However, by the beginning of the ninth century most Chalcedonian church figures in Syria and Iraq were writing in Arabic. The surviving archives of the monasteries of Palestine indicate a transition into Arabic by the end of the eighth century. Griffith (1989) explains the causes thus: Throughout their history the monasteries of Palestine were populated by monks from outside the patriarchate of Jerusalem. But for the most part in earlier times, until well into the eighth century, their important ties were with Cappadocia, Constantinople, and other centers of Greek thought in Byzantium. In the ninth century, however, the monks whom one comes to know from the few personal notices available from the old Palestinian archive of Arabic manuscripts had ties with Edessa (Abu Qurrah), Damascus (Bishr ibn as-Sirri), and Baghdad (Anthony David), as well as with Palestinian towns such as Tiberias (Abraham), and ar-Ramlah (Stephen of Ramlah). And their languages are Syriac and Arabic, rather than Greek (pp. 10-11). Theodore Abu Qurrah, bishop of Harran, who wrote in Greek, Arabic, and Syriac, is one of the earliest figures to use Arabic regularly in his writings, but according to his own testimony he wrote thirty tracts against the Jacobites in Syriac (Griffith, 1997). Furthermore, the later Typicon of Mar Saba, which was used in the monasteries of Palestine at the beginning of Muslim rule, forbids “Syrians” from becoming abbots to avoid “dissensions and quarrels between the two nationalities, that is, the Greek-speakers and the Syriac-speakers,” but gives them preference in all other responsibilities, “because in their lands of origin people are more efficient and practical” (p.16). Such provisions prove the existence of “those whom people called ‘Syriac-speaking’ Chalcedonians in Palestine and elsewhere from the fifth century until well into later centuries, when gradually, after the rise of Islam, both Greek and ‘Syriac’ were eclipsed as day-to-day ecclesiastical languages by Arabic” (p. 16). The same provision also shows that the Greek hierarchy dominated the highest ranks in the patriarchate for the reasons we already discussed in the last chapter. Another provision of this Typicon permits Iberians (Armenians and Georgians) and the “Syrians” to chant the liturgical hours, the daily canon, the Epistles, and the Gospels (nearly all of the services) “in their own language, and afterwards they will come into the great church and participate in the pure, lifegiving Divine mysteries together with the entire brotherhood” (p.16). This provision proves further that while Greek dominated high clergy and was favored over other languages, it was not forced on the Syriac speaking community in Syria and Palestine. This attitude, as we shall see, changes in the Ottoman era with the emergence of Greek nationalism. The Arabic language that is used in the manuscripts of the monasteries of Palestine, the only monasteries where such works survived pillage, contains many deviations from the classical Arabic used by the Muslim Arabs (Blau, 1994). This largely resulted from the transfer of many Syriac forms and loan words into it. Such “deviations occurring in these texts need not reflect Palestinian features, but may also exhibit eastern ones” (p. 15). It is not surprising to find such eastern features in western manuscripts, especially among the Rūm, since some of the major figures who utilized Arabic in Christian works, like Theodore Abu Qurra and Anthony David, come from regions in Mesopotamia, where the Rūm maintained a considerable presence until the end of the Crusades (Rustum, 1960). Unlike Nestorians and Jacobites, the Rūm still retained religious ties with Constantinople and Rome, but in spite of the vibrant activity of Arabic Christianity in Palestinian monasteries, and the large body of literature it produced, one gets the impression from Greek and Latin sources that the monastic centers of Palestine were abandoned in the three centuries that preceded the Crusades. The Frankish Commemoratorium de casis Dei (ninth century), which contains details on monastic communities in Christendom, mentions only in passing the use of “the Saracen language” in the holy land (Griffith, 1989). It is possible that the adoption of Arabic by the Chalcedonian Christians of Syria and Palestine in the ninth and tenth centuries helped isolate them from the rest of Christendom. In addition to that, the Muslims barred Europeans and Eastern Romans from gaining political control or free access to the holy land, and viewed any communication with the west with suspicion. The historian Yahya of Antioch (981-1066) says that the clergy in the east no longer knew who resided over the papacy in Rome, and that from the time of the Sixth Ecumenical Council in 681 until the end of the tenth century only two popes, Agathon (678-682) and Benedictus III (855-858) were recorded in the dyptics of the church under Muslim rule (Rustum, 1960). Knowledge of Greek was probably limited to the clergy and those who made a study of it. However, that knowledge and the allegiances it entailed was a double-edged sword for the hierarchs living under Muslim rule. When Job I, patriarch of Antioch, (813-844) tried to cooperate with the caliphs and support their aims against Constantinople he accompanied the Abbasid caliph Al-Mu’tasem (833-842) to the siege of Ancyra (modern Ankara) where he called on its garrison in the Greek language to surrender. He was regarded a traitor and was answered with stones and insults. In contrast, Patriarch Christophorus of Antioch (960-967) left Antioch when war broke out between the Hamadanis of Aleppo and the Eastern Romans, and resided in the monastery of Saint Symeon until hostilities receded. When he returned to Antioch he faced accusations of communicating with the Eastern Romans and encouraging their cause. He was then beheaded by a Muslim mob and his flock were persecuted (Rustum 1960). A year later, in 968, the Eastern Romans, led by emperor Nicephorus Phocas (962-969), recaptured Syria and northern Mesopotamia, and made sure to tolerate Monophysites whom they resettled in the conquered regions (Treadgold, 1997). This may explain the bilingual inscription in Syriac and Greek found in the monastery of Saint Symeon the Stylite which is dated between 963 and 979 AD (Obermann, 1946). In 985 the Hamadanis destroyed the monastery (Hajjar, 1995). The decline of the Syriac speaking population in northern Syria began with the Persian invasion in 614 and continued with the Muslim invasion in 636, which wreaked havoc on the population and turned this once prosperous area into a war zone between the Eastern Romans and the Muslims. Agriculture and trade were disrupted by political instability, and continuous warfare depopulated the region. The Eastern Roman recovery of northern Syria in 968 was threatened by the Turks, who in 1071 defeated the Eastern Romans in Manzikert and gradually became masters of Anatolia. The last Syriac inscription that indicates the presence of Christianity in the “Dead Cities” of northern Syria is in the monastery of Deir Tell ‘Ade, the residence of the Monophysite patriarchs. Pena (1997) states: “According to the inscription, Patriarch John V erected a defensive tower in 941, an indication of the serious dangers from which the monastery was suffering” (p. 245). The numerous Jacobite monasteries in this area had played a major role in the translation and copying of Greek works to Syriac and Arabic (Hajjar, 1995), but the lack of security and continuous raids against these monasteries led to their abandonment. By “1030 the Monophysite patriarchs definitely abandoned Deir Tell ‘Ade to settle in the monastery of Mar Barsauma, Upper Mesopotamia” (Pena, 1997, p. 246). In 1164 the Muslims reconquered and converted to Islam all of northern Syria, planting there “Muslims from outside, Arabs, Turkomans and Kurds, related to the conquerors by religion” to guard the border against future Christian incursions (p. 246). The Crusades began in 1095 when Pope Urban II (1088-1099) responded to a call from emperor Alexius I (1081-1118) to help the Eastern Roman empire, which was ever diminishing in size and constantly threatened by Turkish raids. The Great Schism between the Church of Constantinople and the Church of Rome had occurred in 1054, but despite the theological differences between the Orthodox east and Catholic west, attempts to recover from that schism continued for the next four centuries. Sources from that period indicate genuine concern over Christianity in the East, which had suffered much under the Seljuk Turks and the Fatimids who established their caliphate in Egypt (Rustum, 1960), especially during the rule of the eccentric Fatimid caliph Al-Hakim (996-1021) who had ordered the destruction of the holy sepulcher in Jerusalem, the holiest site in Christendom, and all churches in his caliphate in 1012 (Treadgold, 1997). After the Crusaders had taken control of Palestine, Greek dominated the liturgical life of the Chalcedonian Orthodox church in Jerusalem. The Latin bishop of Arce, Jacques de Vitry (1160-1240) says in his History of Jerusalem “the Syrians use the Saracen language in their common speech, and they use the Saracen script in deeds and business and all other writing, except for the Holy Scriptures and other religious books, in which they use the Greek letters; wherefore in Divine service their laity, who only know the Saracenic tongue, do not understand them” (Griffith, 1997, p. 29). This source indicates that the lingua franca of the Christian population, at least in the major cities, was Arabic, and that the people did not understand or use Greek for worship. The dominance of Greek, as we shall see later in this chapter, was solidified once more during the Ottoman era when the patriarch of Constantinople became the sole representative of the Rūm millet (Turkish for Milla or “sect”), and control of the church lay in the hands of Greek clergy. The Crusades, which initially began as an enterprise to defend Christianity, resulted in the near destruction of the eastern churches. The Jacobites, who constituted the majority of the population in northern Syria, reached a great state of decline after the Crusades, and the Syriac language lost its vigor as a language of literature because of the instability and ruin that had befallen its speakers. On the other hand, the Rūm in the north suffered as much as their Jacobite counterparts, and their affiliation with, and support for, the Eastern Romans brought Muslim vengeance upon them. The Mamluks, who were warrior slaves from Turkish decent under the Abbasids, ruled the Levant from 1250 to 1517 and seized the last Crusader stronghold in 1291. In 1453 Constantinople, the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire, fell to the Ottomans, who turned south in 1517 and crushed the Mamluks. Najim (2006) suggests that the Syriac language continued to play a major role in the life of the Syrian Rūm community, and that by the second millennium the role of Greek was limited to formal correspondence with the Eastern Roman emperor or the patriarch of Constantinople. For example, a sixteenth century Arabic manuscript of the Typicon of Mar Saba from the monastery of Hamatoura in northern Lebanon contains no Greek words whatsoever, while later service books followed the Greek schema and used Greek headings with Arabic transliteration. By examining this manuscript one concludes that Arabic was already the lingua franca of the population. But the most important feature of this document is that the highlighted section which is meant to direct the reader to a psalm reading is written in Syriac. This clearly indicates the knowledge or familiarity of the monks and laity with the Syriac language. Before the Ottomans gave the Greek patriarchate of Constantinople unprecedented control over all the Rūm, most Syrian churches depended largely on Syriac for liturgical use. All liturgical texts use Greek headings after the seventeenth century, and moves to force Hellenization can be found “in many liturgical manuscripts, such as the Balamand Book of Rubrics (an eighteenth century Typicon), in which the litanies are written in both Syriac and Greek. Almost without exception, all the liturgical translations into the Arabic language were done from Syriac until the beginning of the seventeenth century” (p. 10). Guillaume Postel (1510-1581), who traveled extensively in Syria to collect and study Syriac manuscripts, noted that “Chaldaic or Syriac” is the language used by Christians “who live in all of Syria, but especially by the almost four thousand persons who live around Mount Lebanon” (Kuntz, 1987, pp. 471-472). The majority of manuscripts from the monasteries of the patriarchate of Antioch indicate the continuation of the use of Syriac alongside Arabic. The Garshuni (or Karshuni) script is Arabic written using Syriac letters, and exists almost exclusively in Western Syriac Christian manuscripts in the Syrian Orthodox, Maronite (Coakley 2001), and Greek Orthodox (Najim 2006) churches. This script was probably used between the thirteenth and seventeenth centuries to accommodate those who could speak but not read Arabic. Since Arabic was used in Christian liturgical texts as early as the eighth century, it is unlikely that this script was devised so such books could not be read by non-Christians, especially since many manuscripts have Garshuni and Arabic side by side. To make the script functional with Arabic, “the Syriac alphabet of 22 letters was adapted with diacritical points on certain consonants to make up the extra six letters in Arabic” (Coakley, 2001, p. 186). Based on the above, it seems reasonable to assume that the use of this script signaled the decline of Syriac as a spoken language among rural Christian communities in the Levant, and did most likely assist in the transition from Syriac to Arabic. The ties between the patriarchate of Constantinople and the eastern patriarchates of Antioch and Jerusalem were renewed after the fall of the Eastern Roman empire and the entire Near East under Ottoman control in the sixteenth century, and the patriarch of Constantinople became the representative of the Rūm millet. The Turkish era brought the Greeks control of these patriarchates, and preserving the Greek language under Turkish rule was instrumental in protecting the religious identity of the Orthodox Christian inhabitants of the Ottoman Empire. In the first quarter of the seventeenth century the metropolitan of Aleppo Malatius Karmeh (d. 1634) revised the majority of service books and matched them with the Greek texts. The introduction dated in 1612 of the Arabic service book printed in 1647 states that Malatius “compared the service book in Arabic and Syriac to the Greek text, and found important differences so he made a new translation” (Papadopoulos, 1984, p. 748). The successors of Malatius continued this process in the name of uprooting all heretical influences, and their work was accelerated by the arrival of the printing press. Between 1724 and 1899 the patriarchs of Antioch were all Greeks appointed by the ecumenical patriarchate in Constantinople, and protected by Ottoman authorities. The consequences of Greek domination were the separation of the Melkite Catholics in 1724 in response to Greek hegemony, and the emergence of nationalism through the insistence on using Arabic and electing Arabic-speaking hierarchs in the patriarchate of Antioch. Relations between the Syrian Orthodox and the Greek Orthodox flared over property rights in the eighteenth century, and linguistic identity was again the source of these tensions. The ancient convent of Saidnaya, near Damascus in Syria, contained one of the largest libraries in the east, with books and manuscripts written in Syriac, Greek, and Arabic. Many of these writings were stolen, sold, or burned over the years, and that resulted in the loss of many manuscripts, especially those written in Syriac, which were burned in the days of Patriarch Methodius (1843-1859) for fear that the Jacobites might use them to claim ownership of the monastery. The monastery’s abbess Sa’ada Hilal wrote in her diary: I was a little girl back then, and living with my grandmother, in the days of Abbes Katrina Mbayyed (1834 – 1850)…. The library was full of rare manuscripts in those days, especially in Syriac. The large number of such documents worried the hierarchs, who feared that the Surian [the Syrian Orthodox] would use them as an excuse to prove their claims over the monastery. Thus, they decided to gather and destroy them all to get rid of their evils. So they piled them all up - much was written on deer leather - and began to burn them under the arches (Athanasiu, 1997, pp. 287-289). In the vicinity of the nearby town of Ma’lula the Syriac language (also known as Christian Palestinian Aramaic) is still the vernacular of the population, and until the seventeenth century their liturgy was in Syriac even though they belonged to the Greek Orthodox Church. Athanasiu (1997) notes that the script used in the Syriac manuscripts produced by the Rūm between the tenth and seventeenth centuries is known as the Melkite script, which differs from the scripts used by the Maronites and Jacobites. Publication of Syriac works was the result of increasing interest by western scholars in biblical languages, especially Hebrew and Syriac. Sixteenth century scholars believed that “Hebrew was the sacred tongue, and that Syriac was the first offspring of this holy language” (Kuntz, 1987, p. 472). The first printed Syriac work was the New Testament, and it was published first in Vienna in 1555 by Widmanstadt, and then in Antwerp in 1572 by Plantin as part of his Polyglot Bible (Kuntz, 1987). The first printing press installed in the Arab world was in the Maronite monastery of Qozhaya in Lebanon in 1610, and it published books using the Garshuni script (Fakhouri, 1951). American missionaries in Persia founded a printing press to publish Eastern Syriac texts for the Syriac speaking community of Urmia in 1871 (Hitti, 1961), but the town was destroyed during the Ottoman massacres of Armenians and Assyrians in WWI. The disintegration of the Ottoman Empire and the rise of nationalism among its former subject nations opened the floodgates of change in the religious and ethnic demographics of the Near East. We shall discuss in our next chapter the effect those events had on language distribution, and how such changes mirrored the national and religious struggles of the ever shrinking Christian minorities.

Chapter FOUR Syriac in the Age of Modern Nationalism