This site was last updated on 01 October 2008

The Evolution & History of Wolves

No animal on this planet has evoked more

fear and respect from mankind than the wolf.

Our ancestors heard its

howl. Once again its howl is heard throughout eastern Canada.

It has

returned, smarter and more resourceful than before, and it is staying this time.

This story begins 40 million years ago in North America

Eucyon, the ancestor of all known living Canids

Wolves, Coyotes, and Their Hybrids

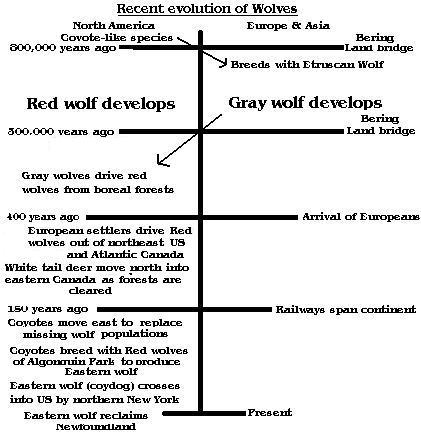

A new species of Wolf has evolved in eastern Canada

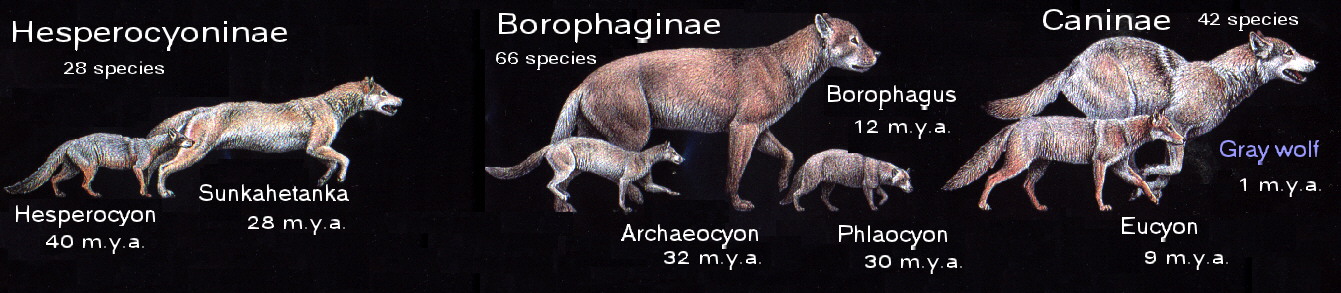

Eocene epoch: The Canidae family evolved from miacids about 40 million years ago in the late Eocene to early Oligocene. The Canidae family is subdivided into three subfamilies, each of which diverged during the Eocene: Hesperocyoninae (~39.74-15 mya), Borophaginae (~36-2 Mya), and the Caninae lineage that led to present-day canids, including wolves, foxes, coyotes, jackals, and domestic dogs.

Oligocene epoch: The earliest branch of the Canidae was the Hesperocyoninae lineage, which included the coyote-sized Mesocyon of the Oligocene (38-24 mya). These early canids probably evolved for fast pursuit of prey in a grassland habitat, and resembled modern civets in appearance. Hesperocyonine dogs became extinct except for the Nothocyon and Leptocyon branches. These branches lead to the borophagine and canine radiations.

Miocene epoch: Around 9-10 mya during the Late Miocene, Canis, Eucyon, and Vulpes genera expand from southwestern North America. This is the point where canine radiation begins. The success of the these canines is the development of lower teeth structure that are capable of both mastication and shearing. Around 8 mya, Berengia offered the canids a way to enter Eurasia, opening up vast new territories to colonize, mingle, and improve.

Early Pliocene: During the Pliocene around (4-5 mya), Canis lepophagus appeared in North America. This dog was small with some being coyote-like. Others were wolf-like in characteristics. It is theorized that Canis latrans (coyote) descended from Canis lepophagus. Around 1.5 to 1.8 mya, a variety of wolves were in Europe. Also, the North American wolf line appeared with Canis Edwardii as clearly identifiable as a wolf. Canis rufus, the Red wolf canine appeared (possibly a direct descendent of Canis edwardii).

Middle Pliocene: Around 0.8 mya, Canis ambrusteri, emerged in North America. A large wolf, it was found all over the continent. It is thought that this species spread to South America where it became the ancestor of the Canis dirus or Dire wolf.

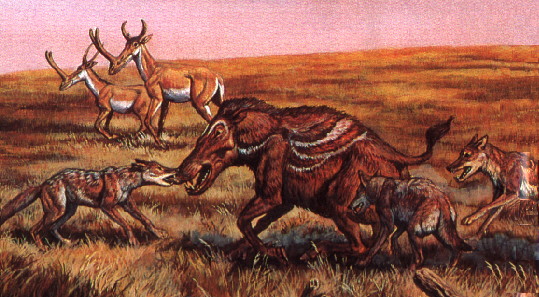

Dire wolf Canis dirus (extinct)

The Dire Wolf, more muscular and heavier than the Grey wolf, evolved earlier, and the two co existed in North America for about 400,000 years. As its prey became extinct around 16,000 years ago due to climatic change, the dire wolf gradually became extinct itself. Around 7,000 years ago, the Grey wolf became the prime canine predator in North America. The Dire wolf has no known descendent alive today with the possible exception of the South American Bush Dog.

They were abundant approximately 10,000 years ago, and became

extinct along with most other North American giant animals (megafauna). The vast

majority of fossils recovered have been from the La Brea Tar Pits in California

and in Florida. It averaged about 1.5 metres (5 feet) in length and weighed about 50

kilograms (110 pounds), though large specimens may have weighed as much as 80kg

(175 pounds). Some Grey wolves were taller, and they all

were faster than this fellow.

They were abundant approximately 10,000 years ago, and became

extinct along with most other North American giant animals (megafauna). The vast

majority of fossils recovered have been from the La Brea Tar Pits in California

and in Florida. It averaged about 1.5 metres (5 feet) in length and weighed about 50

kilograms (110 pounds), though large specimens may have weighed as much as 80kg

(175 pounds). Some Grey wolves were taller, and they all

were faster than this fellow.

The Dire wolf had a larger, broader head and smaller brain-case than that of a similarly-sized Grey wolf, and had teeth that were quite massive. Many paleontologists think that the Dire Wolf may have used its relatively large teeth to crush bone, an idea that is supported by the frequency of large amounts of wear on the crowns of their fossilized teeth. Dire wolf skeletons have been found bearing healed and half-healed injuries similar to the ones found on modern wolves who have been injured while hunting large prey, indicating the Dire wolf also hunted large, live prey.

In total, fossils from more than 3,600 individual Dire wolves have been recovered from the tar pits, more than any other mammal species. This large number suggests that the Dire wolf, like other Canines, probably hunted in packs. It also gives some insight into the pressures placed on this species near the end of its existence.

The Dire wolf never made it to Asia even when there was a land bridge in Berengia. It was a warm-weather animal, used to the thick tropical and sub-tropical forests, and had little inclination to venture into the icy north country plains and tundra where huge herds of Bison and Caribou might have saved it from extinction. No remains of this wolf have ever been found in northern Canada. Where Grey wolves followed migrating herds, the Dire wolf would have been stationary thereby limiting its food source to its known territory. When its prey died off, it disappeared also.

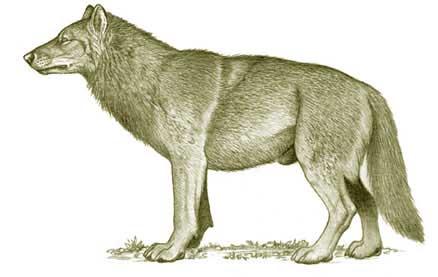

Late Pliocene: At 300,000 years ago, Canis lupus (the Grey wolf) had fully developed and had spread throughout Europe and northern Asia. Berengia offered a way back to North America. At around 100,000 years ago, the Dire wolf, some of the largest members of the dog family, appeared from southern Canada to South America and coast to coast. The Dire wolf shared its habitat with the Grey wolf. Around 7000 - 8000 years ago the Dire wolf became extinct, leaving the continent to the Grey wolf to exploit.

Characteristics: Wild canids are found on every continent, except Antarctica, and inhabit a wide range of different habitats, including deserts, mountains, forests, and grassland. They vary in size from the Fennec fox at 24 cm in length, to the Grey wolf, which may be up to 200 cm long, and can weigh up to 80 kg (180 lbs).

With the sole living exception of the Bush dog, Canids have relatively long legs and lithe bodies, adapted for chasing prey. All canids are digitigrade, meaning that they walk on their toes. They possess bushy tails, non-retractile claws, and a dewclaw on the front feet. They possess a penis bone, which together with a cavernous body helps to create a copulatory tie during mating, locking the animals together for up to an hour. Young canids are born blind, with their eyes opening a few weeks after birth.

Many species live and hunt in packs, and have complex social lives. They are generally highly adaptable, and there may be considerable variation in habits even within a single species.

Modern day wolves: Exhaustive research and dna testing of genetic signatures of wolves throughout North America has recently resulted in a new perspective of North American wolf and coyote populations. The presumed theory until recently was that the Red Wolf (Canis rufus) was restricted to the south eastern US, and the larger Grey Wolf (Canis lupus), was to be found in the northern half of the continent. That is now recognized as not being accurate, eg. the Mexican wolf is a subspecies of the Grey wolf. Also Red wolves are found in eastern Ontario, Canada. In the far south, Canis rufus evolved into the Maned wolf of South America. Isolated by geography, it developed its unique adaptive physical characteristics.

(Author's note: Why the difference between Grey and Gray? Grey is the proper British term, according to the Oxford dictionary. Gray is the revised American choice, according to Webster's dictionary. In Canada, both are used. Since the majority of English-speaking peoples use the British term, in this story, Grey is used to avoid confusion.)

The Bering Land Bridge (Beringia) explained in simple terms

Modern science believes that Ice ages are brought about by changes in the tilt of the earth, as variations in CO2 levels can not explain the absolute rythmatic nature of known ice ages. By studying ice cores, it is known when the most recent ice ages began:

It is also known that the ocean level dropped by about 150 meters during each ice age. The lowest depth in the Bering sea is about 47 meters. By studying pollen in sediment at the bottom of the Bering sea, it is known there was still a land bridge across the Bering sea as late as 11,000 years ago.

.

The areas in the above chart with a blue background are recognized ice ages, when the Bering sea was dry for about 1,000 miles in latitude (north/south), and was covered with land grasses, brush and trees similar to what is found in Alaska today.

It is also known that Amerindians crossed from Asia into North America beginning about 23,000 years ago in three distinct waves of migrations. This fact is proven by tests of teeth structure of many diverse native cultures.

Author's note on the reasons of the wolf's success. Among the classifications that man has placed on animals is that which explains their eating habits. Those that specialize on a narrow range of prey are referred to as "specialists". Those that are not fussy what they eat are considered to be "generalists". By their very nature, generalists are also considered to be "opportunists". Most wolves are opportunists.

Whenever a species of carnivore has become a specialist, it has unalterably linked its future to that of its prey. As long as the prey species flourishes, its specialist predator will flourish. When the prey species disappears, its specialist predator disappears with it. An example of this relationship is the Cheetah and its prey; the Gazelle and the Gnu. It is known by DNA testing that at one time the Cheetah almost disappeared. All surviving Cheetahs today are so close in their dna that they could be brothers of the same family. That situation could only happen if a catastrophe caused their prey species to disappear resulting in mass extinction. The one family of Cheetahs that did survive repopulated the species.

This catastrophe could never happen with wolves as they are opportunists, and will instinctively go after any prey with protein in it. They will even resort to eating roots and grass. The most lethal enemy of wolves is man. If man were to disappear, the wolf would soon regain its rightful place at the apex of the food chain. The only exception to this logic is if a population of wolves becomes addicted to a certain prey to the exclusion of all others. If that happens, that population of wolves would become embedded with their prey and its future

The reason for the eradication of Grey wolves from much of its traditional territory in North America was due to its inability to adapt. It was a creature of habit, and it became tied to its larger prey, and its habitual ways. When the Bison, Caribou and Moose became scarce the Grey wolf perished or moved on while the fate of the Coyote took a different turn. Where a pure wolf will seek isolation from man, the Coyote will thrive in an urban setting. It is a typical contest between brawn and brain, where brain will inevitably win out.

Originally driven from the best hunting grounds, the Coyote evolved into an opportunist lifestyle. Hunting alone, it came to depend solely on its wits. Unlike the wolf, it did not depend on its strength, nor its numbers not even its speed, but its wiles. eg. It has been documented that a Coyote will cooperate with a Badger to catch a rabbit in its underground burrow. In times of scarcity, it would eat grass. Its main diet became mice, moles and small rodents, even grasshoppers. It thrived on its wits and was never eradicated from any of its traditional haunts. When under pressure, it reacted by having two litters a year, and became a better parent.

Unlike the wolf, a mother Coyote (or wolf/coyote Brush wolf) will tolerate another lactating female in her pack. Even in Yellowstone National Park, where Grey wolves were reintroduced from Canada, and despite a devastating decease in their numbers due to wolf predation, the resident Coyote population has quickly evolved and has learned how to take advantage of the presence of its nemesis.

When Red and Grey wolves, were eradicated from much of southern and eastern North America, the stage was set for one of the greatest recent natural expansions of range of any carnivore on earth. Whether that expansion is complete, is anyone's guess.

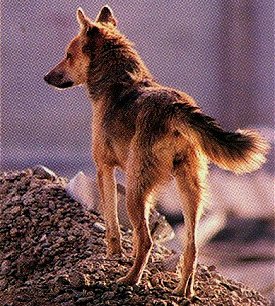

Coyotes Canis latrans

|

|

In Canada, the coyote still inhabits its traditional habitats, the aspen parkland, and short mixed-grass in the three prairie provinces. However, due to the eradication of its larger nemesis, the Grey wolf from much of its former territory, the coyote has spread north to the shores of Hudson Bay, west to the Pacific, and east into Ontario, Quebec, and all four Atlantic provinces.

Coyotes entered Vancouver about 1980 and are now established in the confines of greater Vancouver, both in Stanley Park and about the many golf courses in the city.

The Coyote hybridized

with the northern Red wolf in and

around Ontario's Algonquin Park, has become a more efficient hunter, and

continued spreading east

into Newfoundland. Subsequently, in eastern Canada, where regrowth forests and brush land

on abandoned farmlands does not

favor lone hunters, packs of "Brush wolves" have assumed the pack lifestyle of

their larger wolf cousins.

This

has never sat very well with some naturalists, due to some well known facts regarding

Coyote and Wolf hybridizing in eastern North America.

Reproduction: Female coyotes are monoestrus, and remain in heat for 2–5 days between late January and late March, during which mating occurs. Once the female chooses a partner, the mated pair may remain temporarily monogamous for a number of years. Depending on geographic location, spermatogenesis in males takes around 54 days and occurs between January and February. The gestation period lasts from 60 to 63 days. Litter size ranges from 1 to 19 pups; though the average is 6. These large litters act as compensatory measures against the high juvenile mortality rate, with approximately 50 -70% of pups not surviving to adulthood. Under stress, a female Coyote will have more pups. This unique peculiarity is one major reason why they are so successful.

The pups weigh approximately 250 grams at birth and are

initially blind and limp-eared. Coyote growth rate is faster than that of

wolves, being similar in length to that of the Dhole. The eyes open and

ears erect after 10 days. Around 21-28 days after birth, the young begin to

emerge from the den and by 35 days they are fully weaned. Both parents feed the

weaned pups with regurgitated food. Male pups will disperse from their dens

between months 6 and 9, while females usually remain with the parents and form

the basis of the pack. The pups attain full growth between 9 and 12 months.

Sexual maturity is reached by 12 months

The pups weigh approximately 250 grams at birth and are

initially blind and limp-eared. Coyote growth rate is faster than that of

wolves, being similar in length to that of the Dhole. The eyes open and

ears erect after 10 days. Around 21-28 days after birth, the young begin to

emerge from the den and by 35 days they are fully weaned. Both parents feed the

weaned pups with regurgitated food. Male pups will disperse from their dens

between months 6 and 9, while females usually remain with the parents and form

the basis of the pack. The pups attain full growth between 9 and 12 months.

Sexual maturity is reached by 12 months

In the 1990s, the Ontario government relocated several Grey wolves into south eastern Ontario to help reintroduced Fishers and Cougars in thinning out the overabundant population of White tailed deer, which were being killed on the highways in astounding numbers. In Lanark County alone, it has been estimated that one deer is killed every day on highways.

Solitary male wolves invariably mate (during the last two weeks of February) with any obliging female wolf or coyote they can find. In one instance near Perth, one stationary pack of "Coyotes" was DNA tested. It was determined the Alpha male was a pure Grey wolf, the Alpha female was a Coyote. It has never been found to have occurred the other way around, so it appears that female wolves and coyotes favour larger males. This is now a universally recognized trait of all female coyotes and wolves.

It is now generally accepted that this has been the pattern in and around eastern Ontario since the early 1900s.

The progress of this dramatic "invasion" has been carefully charted; for example, coyotes established themselves in Ontario about 1919. Their Coyote/Red wolf hybrid offspring entered Quebec in the 1940s, in New Brunswick in the 1960s, Nova Scotia in the early 1970s, across the ice to PEI in the late 1970s, and across the winter ice of the Gulf of St Lawrence to Newfoundland by 1985. This remarkably fast expansion was due to the fecundancy of the female Coyote who can theoretically spark a population boom of over 1,000 in three years.

Most astonishingly, coyotes

have been discovered on the shores of Hudson Bay to Panama, and from Alaska to

Newfoundland & Labrador.

They have frequently interbred with southern and northern Red wolves to reclaim their

ancient territories. Pure Coyotes have often found it necessary to penetrate into

U.S. and Canadian cities to escape the predations of their larger

'country-style' hybrid cousins. In their urban haunts, their life

expectancy is doubled.

Most astonishingly, coyotes

have been discovered on the shores of Hudson Bay to Panama, and from Alaska to

Newfoundland & Labrador.

They have frequently interbred with southern and northern Red wolves to reclaim their

ancient territories. Pure Coyotes have often found it necessary to penetrate into

U.S. and Canadian cities to escape the predations of their larger

'country-style' hybrid cousins. In their urban haunts, their life

expectancy is doubled.

During the Autumn of 2007, Ottawa newspapers were full of reports of urban Coyotes killing domestic cats and dogs in the southern fringes of that city. Most of those reports were exaggerations and pure sensationalism (similar to the exaggerated claims of Coyote damage in Newfoundland).

Perhaps with the absence of pure Grey wolves in Newfoundland and the presence in large numbers of Moose and Caribou, Newfoundland may yet be the area where these shape shifters could become the largest Brush wolves in the world. If a new land bridge or even an ice bridge appears across the Bering straight in the foreseeable future, the way will be open for these purely North American opportunists to overwhelm Asia and Europe.

These Coyote/wolf descendents employ the craftiness of the coyote and the pack behavior & strength of the wolf to become a far more lethal threat to domestic livestock than either of its predecessors.

There has been substantial controversy on whether the North American Coyote should, or should not, be classified within the Jackal species. Some go so far as to describe the Coyote as the North American Jackal. One thing is for certain, both Jackals and Coyotes are bonafide members of the Canid family and actually predate wolves. In other words, Jackals (and Coyotes) were the ancestors of all wolves.

The 19 recognized subspecies of Coyote (to date):

-

Mexican Coyote, Canis latrans cagottis

-

San Pedro Martir Coyote, Canis latrans clepticus

-

Salvador Coyote, Canis latrans dickeyi

-

South-eastern Coyote, Canis latrans frustor

-

Belize Coyote, Canis latrans goldmani

-

Honduras Coyote, Canis latrans hondurensis

-

Durango Coyote, Canis latrans impavidus

-

Northern Coyote, Canis latrans incolatus

-

Tiburon Island Coyote, Canis latrans jamesi

-

Plains Coyote, Canis latrans latrans

-

Mountain Coyote, Canis latrans lestes

-

Mearns Coyote, Canis latrans mearnsi

-

Lower Rio Grande Coyote, Canis latrans microdon

-

California Valley Coyote, Canis latrans ochropus

-

Peninsula Coyote, Canis latrans peninsulae

-

Texas Plains Coyote, Canis latrans texensis

-

North-eastern Coyote, Canis latrans thamnos

-

Northwest Coast Coyote, Canis latrans umpquensis

-

Colima Coyote, Canis latrans vigilis

Note: This list is growing, and more subspecies will be added as this purely "North American" canid breaks into South America.

Coydogs and Dogotes

The existence of true coyote dog hybrids, also known as Coydogs or Dogotes, is often the subject of hot debate. This is because, at first glance, the facts seem to be a little contradictory. For instance, there is little scientific evidence of coyotes and dogs breeding in the wild. However, it is a genetic fact that coyotes can breed with dogs and wolves, subsequently producing fertile offspring.

The coyote social structure is somewhat different from the domestic canine, and coyotes would rather eat a dog than befriend one. Coyotes also have very different breeding cycles and mating behaviors. It is believed the male coyote sperm count remains low or dormant for most of the year, and only picks up for about 60 days (maximum) in the Spring in conjunction with the female coyote's once a year heat cycle. Coyote males usually stick with one female through the breeding season as well, even assisting in feeding and raising the puppies.

Some researchers believe they mate for life. Any domestic dog that would have the nerve to solicit the affections of a female Coyote would have to deal with a very irate male Coyote. Then, a female Coyote would have to be very hard up to breed with a lazy non-parenting dog, which in normal circumstances is just something to scorn or eat.

For a coyote and a dog to mate, the choice of female coyotes would have to be so sparse that the male would not have a "girlfriend" to start with, then, he would have to meet a female dog (too large to eat), who just happened to be in heat within the same two month period that he was producing sperm. The above scenario is not impossible, merely impractical.

A Coydog is an offspring from a male Coyote and a female dog. A Dogote is the offspring from a male dog and a female Coyote. So why aren't Coydogs more common? The reason there is little evidence of coyotes mating with dogs in the wild is simply because social habits and statistics makes the opportunity and probability of mating quite low.

Even in the rare occasions when a Coyote and a Dog have mated, the offspring would be fertile but their chances for survival in the wild are practically nil. Even if a litter of Coydogs makes it to breeding age there are more barriers. They inherit the coyote’s annual estrus pattern with one notable derivation - thanks to the good sense of mother nature; The male and female Coydog and Dogote comes into estrus in the Autumn, three to four months before the estrus cycle of wild coyotes. Their only viable mates are either domestic dogs or other Coydogs so once again, pickings are slim.

Then, any litter born to a Coydog or a Dogote would be born in the dead of winter, drastically lessening their chances of survival. Add to that the fact that the male Dogote takes after his daddy - no child-rearing skills - in the wild, these hybrids are an evolutionary dead end.

Evolution of Red

wolves Canis rufus

Untouched by any possible hybridization with Asian canines, the Red wolf of North America, is the older form compared to the Grey wolf.

It was their transient descendent, the Grey wolf of Asia and Europe, that was first domesticated by man and eventually became the household dog, Canis familiaris.

Through the ages, Red wolves hunted in packs and the smaller Coyote was pushed into south western fringe areas where food was scarce and a solitary life-style was necessary.

When new ice ages appeared, and the Bering land bridge returned, some Asiatic Grey wolves returned to their old stomping grounds in North America, following migrating herds of Moose, Elk and Bison.

Until recently, Red wolves were thought to have survived only in the southeastern United States, where they are so endangered they were proclaimed extinct in the wild by the US Wildlife Service in 1980.

The southernmost population of Grey wolves still existing is represented by the Mexican wolf.

There have always been incidents of Grey wolf/Red wolf hybridization in areas where they are in proximity but those populations were relatively scarce and fleeting, eventually replaced with the larger Grey wolf.

DNA tests proved that stuffed wolves exhibited in the north-eastern U.S. at hotels and lodges are actually specimens of the Red wolf. Further studies resulted in recognition of Red wolf subspecies populations in Texas, Mississippi, the Carolinas, and Florida. They remain under intensive scrutiny by wildlife Officers.

A program of captive breeding and reintroduction to the

wild has met with mixed results, as often, the reintroduced animals will readily

hybridize with expanding populations o f Coyote.

f Coyote.

At the beginning of large scale agriculture in eastern Canada, forests were cleared, enticing the Virginia White-Tail Deer northwards. Remnants of the north-east U.S. Red wolf population followed them. Their population centre, and refuge quickly became Algonquin Park in north-eastern Ontario. Tests have proved there were no Red Wolves in this part of Canada prior to the early 1800s. This isolated population comprises the third known population of pure Red wolves on the planet, and it is the southernmost viable population of Red wolves.

Now that second and third isolated populations of Red wolves have been documented in western and eastern Canada, U.S. authorities could use their bloodlines to augment the southern population, and thereby strengthen their genetic pool. However, U. S. parochialism prevents that.

It is not known how many "southern Quebec" pure red wolves remain, or even if this is a viable population. Their viability as a pure strain in south-eastern Ontario is threatened by hybridization with Coyotes inside and outside of Algonquin Park.

To learn more about northern Red wolves, read "Wolf Country" by John B. Theberge (ISBN 0-7710-8563-X.

Through an ironic twist of fate, the smaller Coyote (who was driven out of the best hunting areas by the Reds) has now (through its recent hybridization with Reds) spread its genes throughout eastern North America, an area that is entirely new to its species.

And in another testament to the endurance of the Coyote, most people in these newly expanded areas (except in south-eastern Ontario) refer to the new Brush wolves as "Coyotes". The Americans refer to them as "Coydogs". Similar to their transient cousins in Atlantic Canada, they weigh in at 50 - 60 lbs. To see the Brush wolves that live around my farm, scroll down to "Two Solitudes".

In Canada, there is no such thing as an

"Endangered Species Act". Due to the mine field of

Federal/Provincial politics in this country, the Feds finally hacked out a

"Species at Risk" Act which does not ruffle any Provincial

feathers.

It appears our Federal and Provincial Governments are so arrogant and so tied up in their own "fiefdoms" they cannot contemplate the need for protection of endangered species, nor even to accept the fact that there are wolves in Canada of several species, that require Government protection.

Over time, with each population separated, the northern and southern populations of Red wolf have undoubtedly become substantially different and are already considered separate sub-species of the Red wolf.

The northern Red wolves are substantially larger, darker, and with smaller ears than their southern cousins, typical adaptations of any northern subspecies.

They also form permanent family packs (as do the Grey wolves), while their southern cousins generally do not (they don't have to). (Packs of northern Red wolves have been documented as killing moose.)

Through DNA testing, it has been documented that 13% of the resident Red wolf population in Algonquin Park has been infiltrated with Coyote dna.

Unless checked, this trend may eventually result in the complete extinction of the eastern pure Red wolf population in Canada.

Although this prospect may bring foreboding to some purists, it signals an ironic twist of fate for both the Coyote and the Red wolf.

The vitality and cunning of this new hybrid is remarkable, combining the best of both species.

The fact is each species needed the other to become something better so they could expand their population to areas previously lost by pure Greys.

Canada's Pacific Coastal Wolves

(Subspecies

yet to be determined)

There remains an isolated population of Red wolves in the rain forests of the

islands off the coast of British Columbia, where it is estimated there are approximately about 500 still

remaining. Where their territories overlapped, some hybridization with

Greys occurred.

There remains an isolated population of Red wolves in the rain forests of the

islands off the coast of British Columbia, where it is estimated there are approximately about 500 still

remaining. Where their territories overlapped, some hybridization with

Greys occurred.

They regularly swim from one island to another, and one was documented swimming a distance of 11 km.

These coastal "marine-adapted" wolves comprise the second isolated population of Red wolves in North America.

Although there aren't good estimates of the total population of wolves in coastal British Columbia and Alaska, experts estimate that wolves in southeastern Alaska's vast Alexander Archipelago number fewer than 1000.

Conservationists worry that Government

subsidized logging of the ancient coastal forests poses a threat to these

animals and other wildlife in the region Some naturalists have insisted the B. C.

Coastal wolves are

actually Grey wolves but a comparison of these photos with that of the collared Red

wolf in Algonquin Park immediately above this section indicates to me these are

actually Red wolves.

It has been reported that these wolves will not hesitate to howl in agitation if humans attempt to cross the river which partitions a logged area from an untouched area. Who can blame them?

From their observations and the work of other scientists, researchers say that Canada's coastal wolves generally appear smaller than their continental cousins. This may be because their primary prey, the Sitka black-tailed deer, is much smaller than the prey of wolves living elsewhere, or it may be because Red wolves are naturally smaller than Grey wolves..

Coastal wolf hair also appears to be coarser and better at shedding water, perhaps an adaptation to the heavy rainfall in the region, the researchers speculate. Coastal wolves also behave differently. They feed heavily on salmon during the fall and can swim across sizable saltwater channels to find prey or new territories.

A key question for scientists, conservationist and government officials is whether coastal wolves are different enough to warrant classifying these animals as one or more unique subspecies. Coastal wolf scat and hair samples were sent to scientists at the Conservation Genetics Laboratory at the University of California--Los Angeles for DNA testing.

The results so far indicate that coastal wolves of Canada have several unique genetic sequences, or haplotypes, in their DNA strands. What's exciting about coastal wolves is that we've identified several haplotypes which haven't been identified anywhere else on the continent.

This information adds credence to the argument that coastal wolves are unique, and may have been evolving in isolation over several millennia. It may, for example, undercut the belief common among many scientists that interior wolves repopulated the Pacific coast about 8000 years ago, after the glaciers of the last ice age retreated.

An alternative theory, put forth by biologists from the University of Victoria, is that several large ice-free refuges on the Pacific coast may have allowed groups of wolves and other animals to evolve in relative isolation for as long as 360,000 years.

Canadian Grey Wolves are Transplanted

From Northern British Columbia To Yellowstone National Park

To

Restore The Natural Order

The

Absence of Wolves allowed Coyotes to become the top Predator

The

Absence of Wolves allowed Coyotes to become the top Predator

The absence of a top predator for over 60 years had allowed Coyotes to become so numerous in Yellowstone Park and its surrounding public and private lands (73,000 sq. kms), to throw the entire ecosystem out of whack. A quarter of all gophers, a third of all ground squirrels, and two-thirds of voles ended up in a Coyote's jaws.

Coyotes had packed up and were behaving arrogantly like wolves.

In the mid-1990s, there were more than 80 Coyotes in 12 packs, the densest population ever known. By 1998, this robust population had been reduced to 36 survivors in nine small packs.

Remaining Coyotes have learned to cope with the presence of their larger cousins, and have become scavengers again. In Yellowstone and elsewhere, a Grey Wolf will run down a Coyote and kill it on sight. So these Coyotes have become wary again, and have stabilized as opportunists in a Wolf-dominated world.

Some people claim many of the "wolf-mimicking" Coyotes of Yellowstone fled eastwards adding to the gene pool of the Eastern Coyote/Red Wolf hybrid, although this is rubbish. The first solitary Coyote was spotted in Ontario in 1919, not 1998. The Coyotes that arrived in Ontario, were of the northern 'Canadian' variety (Canis latrans incolatus). The Yellowstone Coyote is prone to be the Mountain Coyote (Canis latrans lestes), a smaller animal. Any later 30 lb. encroaching Coyotes of any sub-species would be chased away by the 60 lb Canis Lycaon hybrid that has taken over as top predator in south-eastern Canada and the north-eastern U.S.

Grey Wolves Thrive in Yellowstone

In 1995, 14 wolves from an area near Hinton, BC, were introduced . The following year, another 17 were introduced from near Fort St. John, BC.

The goal of the program was to establish 10 resident packs of wolves in the park. The population now appears to be leveling off at about 31 packs, with 19 breeding pairs and more than 250 adults.

Due to this historic achievement, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service recently pushed Grey Wolves from endangered to merely threatened in most of the contiguous 48 states.

Grey Wolves Bring A Balance Back To Nature

The decrease in Coyotes has caused rodents to increase in numbers, resulting in a corresponding increase in raptors, fox and raccoons. Elk have taken to the steep slopes rather than browse in the valleys where the wolves den. This has allowed Willows and Aspens to rebound around low-lying wetlands and creeks. Subsequently, beavers have made a reappearance. Five teams of scientists from Canada and the U.S. are presently studying the long term effects of the wolf reintroduction. Those who are involved, claim this is the most significant animal reintroduction in North America.

Although the wolves have had an effect on the shrinking northern Elk herd, the lack of rain and scarcity of browsing has been the major factor affecting the Elk. Elk numbers peaked in the However, the Elk are now healthier and tougher than they once were. Several wolves have been found to have been killed by Elk so they are not as helpless a prey as some have claimed. A healthy Elk in its prime will rarely be brought down by a wolf.

Other fauna benefiting from the reintroduction are: Black and Grizzly bears, Otters, Muskrats, Mink and all types of birds, including the numerous 'Wolf' Ravens who continuously follow the wolves to feast on their kills, and all insects that thrive on plant life.

These studies have brought about a new conception of wolves, wherever we have the good fortune to find them..

Special Update On the United States Fish and Wildlife Service Red Wolf Reintroduction Efforts

The

red wolf is one of the world’s most endangered wild canids. Once common

throughout the southeastern United States, red wolf populations were

decimated by the 1960s due to intensive predator control programs and loss

of habitat. A remnant population of red wolves was found along the Gulf

coast of Texas and Louisiana. After being declared an endangered species

in 1973, efforts were initiated to locate and capture as many wild red

wolves as possible. Of the 17 remaining wolves captured by biologists, 14

became the founders of a successful captive breeding program.

Consequently, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service declared red

wolves extinct in the wild in 1980.

By 1987, enough red wolves were bred in captivity to begin a restoration

program on Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge in northeastern North

Carolina. Since then, the experimental population area has expanded to

include three national wildlife refuges, a Department of Defense bombing

range, state-owned lands, and private property, spanning a total of 1.5

million acres.

An estimated 100 red wolves roam the wilds of northeastern North Carolina

and another 150 comprise the captive breeding program, still an essential

element of red wolf recovery. Interbreeding with the coyote (an exotic

species not native to North Carolina) has been recognized as the most

significant and detrimental threat affecting recovery of red wolves in

their native habitat. Currently, adaptive management efforts are making

good progress in reducing the threat of coyotes while building the wild

red wolf population in northeastern North Carolina.

This population is the only pure-bred wild one recognized by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

(Thanks to U.S. F & W Service and Mark Gelbart)

Maned wolves (Chrysocyon brachyurus)

As

some hardy Eucyon ventured across Beringia to the cold steppes of

Siberia and new horizons there, some adventurous southern relatives wandered

into the heat of South America. A far different landscape awaited them,

and they adapted.

As

some hardy Eucyon ventured across Beringia to the cold steppes of

Siberia and new horizons there, some adventurous southern relatives wandered

into the heat of South America. A far different landscape awaited them,

and they adapted.

To be successful in the vast Pampas, with tall grasses, and the many dangers there, their legs grew longer and their ears enlarged so they could hear night sounds to better compete with the Puma and Jaguar for sustenance.

Until recently, many naturalists assumed these

canids were an entirely separate species but, again, dna tests came to the

rescue, and proved they are indeed a sub species of the Red wolf. In their

adopted homeland, they have filled an empty niche, which in Africa is assumed by

the Cape Hunting dog, the Abyssinian Wolf and the Hyena.

The Maned wolf has the head and coloring of a wolf, the large ears of an African hunting dog, and the body of a hyena. Maned wolves are about 3 feet tall shoulder height, and weigh about 50 pounds. Its body is covered with golden-red fur, and it has black legs with a black mane.

Maned wolves live in monogamous pairs, and mate for life. They are solitary like our western Coyotes, and only interact during their brief breeding season which begins in April.

In August and early September mothers give birth to 2-5 Maned wolf pups. In captivity, males help raise pups by regurgitating food. Captive Maned wolves live between 12-15 years.

The Maned wolf lives in the tropical savannah and scrub forests of South America - specifically, northern Argentina, Paraguay, eastern Bolivia, and southeastern Peru.

Maned wolves are omnivorous and nocturnal, preferring to rest under forest cover during the day and hunt until sunrise. They are very shy, and only attack humans when they feel threatened.

It is estimated there are between 2200 - 4500 Maned wolves remaining.

When I first claimed on this web site that Maned wolves were related to Red wolves, I received a few angry denials from some sanctimonious "experts". Well, I guess I have the last laugh now.

It would not surprise me to learn that someday, those responsible for labeling animals with those fancy scientific Latin names, will modify this fellow's label to put him generically alongside his brethren in North America, right where he belongs.

Gr

ey wolves Canis lupusGrey wolves are considerably larger (typical 170 lbs) than are red wolves (typically 60 - 100 lbs), and they come in white, black or grey but have no redness as is so evident in red wolves.

When Europeans began settling eastern North America, they hunted resident

red wolves into extinction in the north-eastern U.S. and in Canada's Atlantic

provinces.

Remnant populations followed deer herds north into south- eastern Ontario and south- western Quebec, or retreated into the swamps of the Carolinas.

The southern population became isolated and its gene pool became minuscule.

However, in the north, Red wolves replaced Grey wolves where the latter were driven into near extinction.

Until recently, Grey wolves were routinely shot by Government hunters even in Algonquin Park.

This genocidal practice allowed invading red wolves a better chance to establish a foothold in Algonquin Park, where they survive in endangered numbers today.

As railways and farming spread westward, the Coyote traveled east to fill in a void left by his larger nemesis.

In 1919, Coyotes were documented in Ontario, hybridized with the Red wolves of eastern Ontario, and eventually crossed the St. Lawrence winter ice-cover south into New York state.

The Americans called them "Coydogs" and eradicated them on sight.

In the relatively protected Algonquin Park region, three separate species of wolf were dna documented.

* Grey Wolves in northern areas of the

park (Canis Lupus).

* Grey Wolves in northern areas of the

park (Canis Lupus).

* Red Wolves in central areas of the Park (Canis Rufus). (Incl some

hybridization with Grey wolves).

* Hybridized Red Wolf/Coyote populations in the southern and south-east

fringes of the

Park.

By far the most successful of these populations were the latter, successfully combining the craftiness of the Coyote and the larger size of the Red Wolf, they expanding outwards in all directions, with an emphasis towards the east, where pure Grey wolves had been entirely eliminated.

The Grey wolf once inhabited most, if not all, of the Northern Hemisphere. Excluding modern man, the wolf was the most widely distributed land mammal that ever lived.

There were once at least thirty

different subspecies of wolf. Most have become extinct. About five

subspecies survive today. Wolves are able to survive anywhere there is adequate

food and human tolerance.

The Finnish wolf population was hunted down in the 1920's. At present there are

about 200 wolves living in Finland.

In the whole of Russia there are about 30,000 wolves, but

in Karelia, only about 350 individuals.

The North American Eastern Grey Wolf

Canis lupus Lycaon

Eastern Canada’s population of Eastern

Wolves, a sub-species of the Grey Wolf, is primarily found in southeastern Ontario

and

southwestern Quebec. This range includes La Mauricie National Park of Canada.

The Eastern Wolf is fairly small and fawn-coloured, with black on its back and sides, and red-brown behind its ears. In the Mauricie region, male Eastern Wolves stand about 80 cm (32 inches) at the shoulders and weigh around 40 kg (88 lbs), while females measure about 75 cm (30 inches) at the shoulders and weigh approximately 30 kg (66 lbs). It is the smallest subspecies of grey wolf except for the Mexican Wolf.

The Eastern Wolf needs large areas of forest- either deciduous, coniferous, or mixed - to survive. It is a shy mammal, easily disturbed by human presence and activity.

In May 2001, COSEWIC listed the Eastern Wolf as a subspecies of special concern because it is so vulnerable to human activity. Throughout its range, the Brush Wolf (Western Coyote/Red Wolf hybrid), which is approximately the same size, has interbred with it, and it is difficult to tell them apart without resorting to dna testing.

More Government

sponsored testing is required to enable scientists to obtain a better picture

and appreciation for this endangered species of wolf, and the Brush wolf dna contamination.

More Government

sponsored testing is required to enable scientists to obtain a better picture

and appreciation for this endangered species of wolf, and the Brush wolf dna contamination.

The Eastern Wolf is an important part of La Mauricie National Park’s ecosystem. It feeds on prey like deer and moose, helping keep their populations at sustainable levels. This helps maintain both the diversity and richness of park vegetation, and the ecological integrity of the entire forest ecosystem.

Two wolf packs, with 5 to 10 members each, currently roam the small, 536 km2 national park. Yet their movements often take them beyond the park’s boundaries, where they are no longer protected.

Eastern Wolves often fall victim to trapping, hunting, and road traffic. They are timid and easily disturbed by logging and recreational activities. Critical wolf habitat continues to be lost to agriculture, the timber industry, and urban expansion.

Many people have misguided

perceptions about wolves. Some are afraid of wolves. Others view them as

predators that threaten livestock and wildlife like deer and moose. People

often don’t realize how important wolves are to ecosystem health.

Using information gathered through the research program, Parks Canada is taking steps to ensure the survival of the Eastern Wolf, including:

-

developing a conservation strategy for protecting Wolves inside and outside the park.

-

creating an education program about the importance of wolves to the region’s forest ecosystems, to change perceptions of the wolf.

Status

Hopefully Eastern Wolf populations will stabilize and even grow in and around La Mauricie National Park once the conservation strategy is implemented.

In the meantime, the two wolf packs are still being monitored. Parks Canada is seeking to understand how the wolves use their habitat inside and outside the park, and to determine the long-term impacts of human activity on wolf populations.

Steppe Wolf Canis lupus campestris

Asian Steppe wolves are not protected, and are numerous in Mongolia. They are not white as are many more northerly Siberian wolves. Most Mongolian wolves are the colour of the desert to blend in. They eat almost every animal they can catch. Wolves usually hunt in packs, but sometimes one wolf hunts on its own. A pack of wolves can take down animals much larger and stronger then themselves as moose, deer, horses and bulls. Wolves are very intelligent creatures, maybe the most intelligent animals besides humans.

These

wolves are strictly carnivorous. Wolves do not kill for sport, but for

survival in Mongolia's harsh climate. Wolves hunt just about everything

that will provide a meal for them. Depending on the area in which they

live and the time of season, they hunt everything from large birds to large

mammals to small ones.

Wolves usually prey upon the sick, weak, and old animals that they come across. It is much easier for them to hunt these animals then it is a full grown healthy one. By killing off the weak animals, wolves help strengthen the herd of which they take their weak prey from.

An old or unhealthy animal can be a burden to its herd. For example, an aged caribou eats food that other caribou need to raise their young. A sick elk could infect other members of the herd. Wolves eliminate such animals performing an important natural function by maintaining the health of their prey species.

Mongolian wolves are liable to hunt domestic animals of nomadic families at any time day or night. They hunt when they are hungry but if they are not successful they can go without food for several weeks.

The pack defends and guards its territory from intruding wolves. Their territory size depends on the availability of prey. If prey is scarce, the territory may cover as much as 800 square miles (2,100 square kilometers). If prey is plentiful, the area may be as small as 30 square miles (77 kilometers). After a successful hunt, the pack will gorge on the kill. They have large stomachs, enabling them to eat 20 pounds (9 kilograms) of meat or more. Wolves can go without food for weeks at a time.

Wolf

pups live on only mother's milk for the first three weeks of their life.

After three weeks they begin to eat meat. The pups' parents bring the

meat to the pups by carrying it in their stomachs. The pups then lick

the mouths of the older wolves to get them to regurgitate the food. The

pups then eat the coughed up food. This goes on until the fall when the

pups begin to hunt with the rest of the pack.

Wolf

pups live on only mother's milk for the first three weeks of their life.

After three weeks they begin to eat meat. The pups' parents bring the

meat to the pups by carrying it in their stomachs. The pups then lick

the mouths of the older wolves to get them to regurgitate the food. The

pups then eat the coughed up food. This goes on until the fall when the

pups begin to hunt with the rest of the pack.

WOLVES

IN MONGOLIA: The habitat of the wolf covers huge territories from the

Western Altai's borders to the Eastern steppes. The population of this

highly-adaptable animal has been stable for years, and in some areas has

increased, causing damage to game and livestock. The largest wolves

found in Mongolia may reach 2 meters (about 7 ft.) from the tip of the nose

to the tip of the tail and weigh up to 100 kg.(220 lbs).

Mexican wolf Canis lupus baileyi

Mexican wolves are the smallest subspecies of North American

Grey wolves.  They are also the most endangered. Commonly referred to as "El lobo,"

the Mexican wolf is grey with light brown fur on its back. Its long legs and

sleek body enable it to run fast.

They are also the most endangered. Commonly referred to as "El lobo,"

the Mexican wolf is grey with light brown fur on its back. Its long legs and

sleek body enable it to run fast.

Height 26-32 inches at the shoulder. Length 4.5-5.5 feet from nose to tip of tail. Weight 60-80 lbs. Males are typically heavier and taller than the females. Lifespan Up to 15 years in captivity.

Diet: Staples Ungulates (large hoofed mammals) like white-tailed deer, mule deer and elk. Also known to eat smaller mammals like rabbits, ground squirrels and mice.

Population: Once extirpated from the southwestern United States, 34 wolves returned to southeastern Arizona following a reintroduction program begun in March, 1998. There are only about 200 Mexican wolves in captivity. The goal of the reintroduction program is to restore at least 100 wolves to the wild by 2008.

Range:

Mexican wolves once ranged from central Mexico to southwestern Texas,

southern New Mexico and southeastern Arizona. Today, the Mexican wolf has been

reintroduced to the Apache National Forest in southeastern Arizona and may move

into the adjacent Gila National Forest in western New Mexico as the population

expands.

Range:

Mexican wolves once ranged from central Mexico to southwestern Texas,

southern New Mexico and southeastern Arizona. Today, the Mexican wolf has been

reintroduced to the Apache National Forest in southeastern Arizona and may move

into the adjacent Gila National Forest in western New Mexico as the population

expands.

Behavior: Mexican wolves prefer to live in mountain forests, grasslands and shrublands,

and are very social animals. They live in packs, which are complex social

structures that include the breeding adult pair (the alpha male and female) and

their offspring. A hierarchy of dominant and subordinate animals within the pack

help it to work as a unit.

Reproduction: Mating Season Mid February-mid March. Gestation: 63 days. Litter size: 4-7 pups. Pups are born blind and defenseless. The pack cares for the pups until they mature at about 10 months of age.

Missing from the landscape for more than 30 years, the howl of the Mexican Grey wolf can once again be heard in the mountains of the southwestern United States. The Mexican wolf, like many species protected by the U.S. Endangered Species Act, is getting a second chance to play its role in nature through an ambitious recovery program.

Unlike the Brush wolves of eastern Canada, there is no Coyote dna in this wolf. Although similar in size, it is a creature of habit, and is more timid. It is not as brazen and wily as is the Brush wolf. It will kill and displace any coyotes it can catch.

European wolves Canis lupus lupus

The Eurasian Wolf (Canis lupus lupus), also known as the Common Wolf, European Wolf, Carpathian Wolf, Steppe Wolf, Tibetan Wolf and Chinese Wolf is recognized as a subspecies of the Grey wolf (Canis lupus). Originally spread over most of Eurasia, with a southern limit of the Himalayas, the Hindukush, the Koppet Dag, the Caucasus, the Black Sea, and the Alps, and a northern limit between 60° and 70° northern latitude, it has been pushed back from most of western Europe and Eastern China, surviving mostly in Central Asia.

European wolves typically have shorter, denser fur than their North American counterparts. Their size varies according to region, though as a whole, adults stand at 30 inches (76 cms) at the shoulder and weigh around 70-130 lbs (32-59 Kgms), with females usually being about twenty per cent smaller than males. The heaviest known European wolf was killed in Romania, and weighed 158 lbs (72 kilograms). Colour ranges from white, cream, red, grey and black, sometimes with all colors combined. Wolves in central Europe tend to be more reddish coloured than those in Northern Europe indicating the original proto-wolf transient from North America was reddish.

Currently, it has the largest range among any wolf

subspecies and is the most common in Europe and Asia. European wolves, like most all others, live and hunt in packs which

are extended families of an alpha male, his mate, and

their offspring. They usually stay within a home range, but may wander

far outside their territory to hunt. They hunt and kill game up to 10

times heavier than their own weight. Wild reindeer, elk, and red deer

are their favorite prey. European wolves will also eat much smaller

animals such as mice and frogs. Because of the decline in the number of

wild game, they have begun to prey on domestic horses, cattle, and dogs.

Starving wolves will even eat potatoes, fruits, buds, and lichen.

The alpha male and female mate between January and March. The cubs are born seven weeks later in a den dug among bushes or rocks. The male brings food back to the den, either by carrying it whole or by swallowing and then regurgitating it for the others to eat. As the cubs grow, the mother and other members of the pack help to feed them.

To a North American viewer, these wolves have a predominant reddish hue that North American Grey wolves don't have. This could be an inherited coloration caused by their Eucyon ancestry which was maintained by their ancestors' non-hybridization with white Asian wolves.

Few European countries still have substantial numbers of wolves. Wild wolves are hard to count, so exact numbers are not known. Sometimes radio-tracking is used to determine their numbers. European wolves have managed to survive only in the most remote, mountainous, or densely forested regions. Areas in which these wolves can live without coming into conflict with humans are decreasing. There is little effective international agreement about the wolf's conservation. All efforts to preserve the wolf are conducted locally.

Because of the increasing shortage of natural prey in

Central Europe, some wolves

have been forced to give up their pack-hunting habits, and scavenge for

food around villages and farmhouses. Projects which are financed by the World Wide Fund for Nature may enable

small numbers of wolves to survive if farmers and herdsman can be

persuaded to accept them.

Because of the increasing shortage of natural prey in

Central Europe, some wolves

have been forced to give up their pack-hunting habits, and scavenge for

food around villages and farmhouses. Projects which are financed by the World Wide Fund for Nature may enable

small numbers of wolves to survive if farmers and herdsman can be

persuaded to accept them.

In Norway, wolves are protected to the extent that they are illegal to be killed by anyone other than farmers protecting their livestock. Similar to most Canadian provinces, farmers are often compensated for livestock which is killed by the endangered wolves. Similar to Canada, the wolves often get blamed even though dogs are often the culprits.

"Grupo Lobo" was founded in Spain and Portugal in 1985 in an attempt to protect the wolves in the mountains on the Spain/Portugal border. Only in Spain is the wolf making a determined resurgence. There is an extremely small number of wolves in Sweden, regardless of protective legislation. These systems are often abused. Lapp herdsman in the North of Sweden have often blamed the deaths of their reindeer on wolves rather than on poor care. The "wolf-plague" in Scotland resulted in the extermination of the animal there.

The last British wolf died in 1743. Wolves survived in Ireland until about 1773. Similar waves of wolf persecution on the European continent has driven the few survivors into remote areas far away from human settlement. In Britain, there are some circles that are promoting the reintroduction of wolves into Scotland and parts of rural England and Wales. It appears that most British farmers are against this idea.

Although the wolf is a protected species in most European countries, some hunters see no reason to stop killing wolves for sport, and will pay a great deal of money for the privilege. Wolf survival in Europe obviously requires more than simple legislations. These wolves are rather shy and intelligent, yet they are still viewed as a ruthless predator by the mainstream.

European Wolf/Dog Hybrids

Throughout Europe, these dogs and wolves will occasionally mate, and their offspring are often impossible to distinguish from ordinary dogs.

The wolf-dog's (right) deceptive appearance makes it all that more dangerous. Wolf-dogs may wander freely through populated areas, unrecognized as wolves.

These hybrids are often wilder than their feral parents. They can be extremely ferocious. Europeans are wary of them due to ancient folklore and the possibility of rabies.

The reddish hue of European Wolves is usually striking in these hybrids. North American wolf/dog hybrids are only reddish when they cross with a Red wolf.

Pure strains of Grey wolf in North America do not have any red coloration

Czechoslovakian (CsV) Wolfdog

The CsV is a relatively new breed of dog that traces its original lineage to an experiment conducted in 1955 in the former Czechoslovak Soviet Socialist Republic (CSSR). After initially breeding a German Shepherd dog with a Carpathian wolf, a plan was worked out to create a wolf/dog breed that blended the desired qualities of both animals. It was officially recognized as a national breed in the CSSR in 1982. In 1999, it became FCI standard no. 332, group 1, section 1.

Both the build and the hair of the CsV are reminiscent of a wolf. The lowest dewlap height is 65 cm for a dog and 60 for a bitch and there is no upper limit. The body frame is rectangular, ratio of the height to length is 9:10 or less. The expression of the head must indicate the sex. Amber eyes set obliquely and short upright ears of a triangle shape are its characteristic features. The set of teeth is complete (42); very strong; both scissors-shaped and plier-shaped setting of the dentition is acceptable. The spine is straight, strong in movement, with a short loin. The chest is large, flat rather than barrel-shaped. The belly is strong and drawn in. The back is short, slightly sloped, the tail is high set; when freely lowered it reaches the tarsuses. The fore limbs are straight, and narrow set, with the paws slightly turned out, with a long radius and metacarpus. The hind limbs are muscular with a long calf and instep.

The color of the hair is from yellow-grey to silver-grey, with a light mask. The hair is straight, close and very thick. The CsV is a typical tenacious canterer; its movement is light and harmonious, its steps are long.

Temperament:

The Wolfdog is more versatile than

specialized. It is quick, lively, very active, fearless and

courageous. Shyness is a disqualifying fault in CsV competitions.

The CsV develops a very strong social relationship not only with their owner, but with the whole family. It can easily learn to live with other domestic animals which belong to the family; however, difficulties can occur in encounters with strange animals. It is vital to subdue the CsV's passion for hunting when they are puppies in order to avoid aggressive behavior as an adult. The puppy should never be isolated in the kennel; it must get used to different surroundings, for traveling and so on. Female CsVs tend to be more easily controllable and both genders often experience a stormy adolescence.

The CsV is very playful and temperamental. It learns easily. However, it does not train spontaneously, the behavior of the CsV is strictly purposeful - it is necessary to find motivation for training. The most frequent cause of failure is usually the fact that the dog is tired out with long useless repetitions of the same exercise, which results in the loss of motivation.

These dogs have admirable senses and are very good at following trails. They are very independent and can cooperate in the pack with a special purposefulness. If required, they can easily shift their activity to the night hours. Sometimes problems can occur during their training when barking is required. CsVs have a much wider range of means of expressing themselves and barking is unnatural for them; they try to communicate with their masters in other ways. Generally, to teach CsV stable and reliable performance takes a bit more time than does to teach traditional specialized breeds.

Saarloos Wolfhond

This

breed of dogs derives his name from, Mr. Leendert Saarloos.

Mr. Saarloos strived for a breed of dogs without degenerative symptoms,

and with a natural resistance against all sorts of diseases.

Although Mr Saarloos was interested in genetics, he approached this

mostly from his practical experiences. Before he started to breed

the Wolfdog, he crossed many other animals such as mice, rabbits,

pigeons etc.

He

chose the wolf as the ancestor of his new breed because it has a lot of

the desired properties he desired.

In the beginning, there

was the German Shepherd male dog, Gerard van Fransenum together with the

female wolf Fleur, which he bought from the Blijdorp zoo. This

couple had 28 puppies from which 3 were good enough to proceed

with. At the advice of a Dutch expert in genetics, Dr. L.

Hagendoorn, the brother and sisters were matched.

He

chose the wolf as the ancestor of his new breed because it has a lot of

the desired properties he desired.

In the beginning, there

was the German Shepherd male dog, Gerard van Fransenum together with the

female wolf Fleur, which he bought from the Blijdorp zoo. This

couple had 28 puppies from which 3 were good enough to proceed

with. At the advice of a Dutch expert in genetics, Dr. L.

Hagendoorn, the brother and sisters were matched.

In

1963 he chose a new female wolf, Fleur II, to counteract

in-breeding. After many disappointments he had a new race, the

"Saarloos Wolfhond".

The

Saarloos Wolfhond is a powerful, wolflike, thick-hairy dog with a

withers height 65-75 cm. for a male, and 60-70 cm. for a female.

The oval bone is powerful but not big. Its structure is harmonious

with tall legs. Males and females are very different in appearance

and airs.

The

Saarloos Wolfhond must exhibit an image of a careful, attentive and

devoted dog that is reserved. It must not be nervous around

strange people and circumstances. It is very cautious, and

exhibits the power of reaction of the wolf with the devotion of the

dog. The primary characteristic of the breed is an

independence of action which is why it is such a great guide dog for the

blind.

Appennine (or) Italian Wolf Canis lupus italicus

The

Appennine Wolf, is a subspecies of the Grey wolf found in the Appennine Mountains

of Italy, and is also called the Italian wolf. It was first described in

1921, and was recognized as a distinct subspecies in 1999. Recently,

due to an increase in population, the subspecies has also been spotted in areas

of Switzerland and Southern France, particularly in the Parc National du

Mercantour. It is federally protected in all three countries.

The

Appennine Wolf, is a subspecies of the Grey wolf found in the Appennine Mountains

of Italy, and is also called the Italian wolf. It was first described in

1921, and was recognized as a distinct subspecies in 1999. Recently,

due to an increase in population, the subspecies has also been spotted in areas

of Switzerland and Southern France, particularly in the Parc National du

Mercantour. It is federally protected in all three countries.

This is a medium sized subspecies by Grey Wolf standards. Males have an average weight of 24-40 kilograms (53-88 lbs, with females usually being about 10% lighter. Body length is usually 100-140 cm (39-55 inches). Fur colour is commonly blended grey or brown, though black specimens have recently been sighted in the Mugello region and the Tuscan-Emilian Apennines.

Comparative studies on Italian wolves, Eastern

European wolves and feral dogs, showed that Italy's wolf population was the

purest, and least affected by hybridization with domestic dogs in Europe.

However, in 2004, three wolves were found in the south-central Tuscan province

of Siena, sporting dewclaws on their hind legs, indicating some dog

contamination in the gene pool. Though this has caused concern on the danger

posed to the wolf's genetic purity, some biologists are encouraged by such an

obvious symptom, as it is a potentially useful factor in diagnosing hybrids.

Comparative studies on Italian wolves, Eastern

European wolves and feral dogs, showed that Italy's wolf population was the

purest, and least affected by hybridization with domestic dogs in Europe.

However, in 2004, three wolves were found in the south-central Tuscan province

of Siena, sporting dewclaws on their hind legs, indicating some dog

contamination in the gene pool. Though this has caused concern on the danger

posed to the wolf's genetic purity, some biologists are encouraged by such an

obvious symptom, as it is a potentially useful factor in diagnosing hybrids.

Diet:

The Italian Wolf is a nocturnal hunter which feeds

primarily on medium sized animals such as Chamois, Roe Deer, Red Deer, and Wild

Boar. In the absence of such prey items, its diet will also include

small animals such as hares and rabbits. An Italian wolf can eat up to

1,5-3 kg of meat a day. It will occasionally consume berries and herbs for roughage.

The wolf has adapted well in some urbanized areas and as such, will usually not

ignore refuse or domestic animals.

Behaviour and reproduction: Due to a scarcity of large prey, wolf packs in Italy tend to be smaller than average. Packs are usually composed of a reproducing alpha pair and juveniles which remain with their birth family until they're old enough to disperse and produce cubs. However, in areas where large herbivores such as deer have been reintroduced, such as the Abruzz o National Park, packs consisting of 6-7 individuals can be found.

Mating occurs in mid- March with a 63 day gestation period. The number of cubs born is dependant on the mother's age, usually ranging from two to eight cubs. Cubs weigh 250-350 grams at birth and open their eyes at the age of 11-12 days. They are weaned at the age of 35-45 days and are fully able to digest meat at 3-4 months.

History: Until the end of the 19th century, wolf populations were widespread across Italy's mountainous regions. By the dawn of the 20th century, the persecutions began and in a short amount of time, the wolf was wiped out in the alps, Sicily and drastically reduced in the Apennine regions.

After the second world war, the situation worsened and the wolf populations reached a historic minimum in the 1970's. In 1972, Luigi Boitani and Erik Zimen were tasked with leading the first Italian investigation into the wolf's plight. Using an area between the Sibillini and Sila mountains as reference points, the duo concluded that the wolf population was composed of a maximum of 100-110 animals.

Italian population: Starting from the 1970s, political debates began favouring the increase in wolf populations. A new investigation began in the early 1980s, in which it was estimated that there were now approximately 220-240 animals and growing. New estimates in the 1990s revealed that the wolf populations had doubled, with some specimens taking residence in the Alps, a region not inhabited by wolves for nearly a century. Current estimates indicate that there are 500-600 Italian wolves living in the wild. Their population is said to be growing at a rate of 7% annually.

French population: Wolves migrated from Italy to France as recently as 1992. The French wolf population is still no more than 40-50 strong, but the animals have been blamed for the deaths of nearly 2,200 sheep in 2003, up from fewer than 200 in 1994. Controversy also arose when in 2001, a shepherd living on the edge of the Mercantour National Park survived a mauling by three wolves. Under the Berne Convention wolves are listed as an endangered species and killing them is illegal. Official culls are permitted to protect farm animals so long as there is no threat to the species.

In northern Spain, a lone wolf was recently DNA tested, and it was determined it was of Italian origin. So the Italian wolf has traveled from the Italian Apennines to the Spanish Pyrenees.

Iberian wolf Canis lupus signatus

Spain is one of the last remaining refuges of the European

wolf. The Iberian wolf population is slowly recovering from its 1970 low

of 400-500 odd individuals with current (2003) figures estimated at as many as

2,000-2,500, almost 30% of European wolf numbers outside Russia. There are

several reasons for the rise in the wolf population .

The Iberian wolf is distinguished by its overall redness, and the black marks along its tail, back, jowls and front legs, and so sigantus meaning marked. More than 50 % are found in Northern Castilla y León (1000-1.500 individuals), and less than 35% in Galicia (500-700), with the densest population in North-eastern Zamora (5-7 wolves/100km2).

Though wolves were once present throughout the Peninsula, they are now confined to the North-east, and a few residual populations in the Sierra Morena (Jaén and Cuenca). Recently, however they have managed to cross back over the modern-day barrier of the river Duero and begun to spread southwards and eastwards: two packs have been detected around Guadalajara and have started to move into Teruel in southern Aragon, much to the amazement and trepidation (and at first disbelief) of the locals.

There are thought to be some 300 breeding pairs in Spain, giving a total number of around 1,500 at the start of spring and around 2,000 by mid autumn (1988 figures see below). The wolf in Spain is no longer considered endangered, merely vulnerable, though the Sierra Morena and Extremaduran populations are classified as critically endangered, and the latter is almost certainly extinct. Wolves in the Sierra Morena inhabit private game estates where they are illegally persecuted as they come into conflict with the hunting practices of the rich. Across the border in Portugal, there are reckoned to be between 46 and 62 packs.

Reasons for the recent increase in the Iberian

wolf population: Until the early 1970s, the wolf was

‘officially'

considered as a pest in Spain, and the government paid out bounties for dead

wolves and distributed strychnine to landowners and peasants. At the time,

many saw the wolf as a mark of a Third World country, in contrast to

‘civilized' nations like France and Britain who had successfully eradicated

their wolf plagues. On occasions in the past, persecution was widespread

and crushing. An act passed by Principality of Asturias details that

between March and December 1816, bounties were paid out for the death of 76

adult and 414 young wolves.

‘officially'

considered as a pest in Spain, and the government paid out bounties for dead

wolves and distributed strychnine to landowners and peasants. At the time,

many saw the wolf as a mark of a Third World country, in contrast to

‘civilized' nations like France and Britain who had successfully eradicated

their wolf plagues. On occasions in the past, persecution was widespread

and crushing. An act passed by Principality of Asturias details that

between March and December 1816, bounties were paid out for the death of 76

adult and 414 young wolves.

The historian Juan Pablo Torrente concluded

that the hunting of wild beasts, including wolves, bears and foxes represented,

‘in absolute and relative terms, a considerable source of wealth' for local

populations. The lobero or wolf-hunter was a respected county figure until

relatively recently, and a whole range of ingenious traps have been devised over

the centuries to catch wolves. All are now illegal. It is however

still legal to hunt wolves in most of Spain. In most of its range, the Law

states that the species must be respected as long as it does not come into

conflict with human interests.

While hunting itself does not necessarily pose a big threat for the Iberian wolf, as most hunts end in failure, the Law gives carte blanche for indiscriminate hunting in most areas. North of the River Duero, only the municipality of Muelas de los Caballeros in north of Zamora, where the densest Spanish wolf populations are found, has shown any real interest for its conservation. Protection is, however, much stronger south of the Duero where the Iberian wolf populations are far more fragile.

Secondly, in the last 40 years, there has

been a huge migration of people from the country to the towns. This depopulation

has led to the regeneration of natural vegetation in former agricultural areas

and the huge increase in prey species such as roe deer and boar. Just drive or

take a train across central and northern Spain and you will appreciate the

immensity and emptiness of the landscape, and it potential to support rich and

varied fauna.

Thirdly, people's attitudes have changed. While there is still much

suspicion, when not outright hate, among some rural populations, many in Spain

now see the wolf as an animal worthy of protection. That great Spanish

populist of nature, Félix Rodríguez de la Fuente,

played no small part in this conversion. Millions of homes in Spain in the

nineteen-seventies were captivated by his television series, ‘El Hombre y la

Tierra', of which the wolf was the star of the show. Rodríquez used

wolves he had raised himself from cubs living in a semi-wild fenced estate for

the film. But, for all its trickery, the episodes on el lobo still stand

out as superb and beautiful piece of nature documentary, and holds a rightful

place in contemporary Spanish culture.

Arabian wolf Canis lupus arabs

The Arabian wolf is a subspecies of

the Grey wolf which was once found throughout the Arabian Peninsula, but

now only lives in small pockets in Oman, Yemen, Jordan, Saudi Arabia,

and probably in some parts of the Sinai Peninsula of Egypt. In Isreal, there are between 100 and 150 Arabian wolves all over the

Negev and the Ha'arava.

In Isreal, there are between 100 and 150 Arabian wolves all over the

Negev and the Ha'arava.