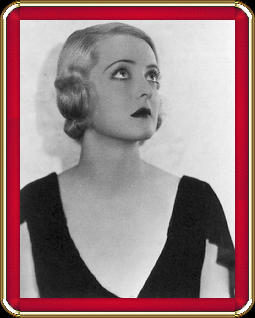

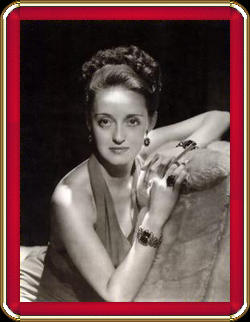

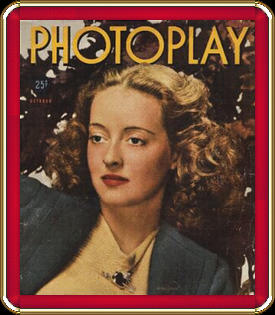

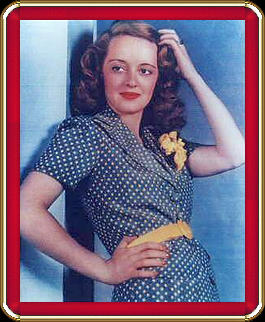

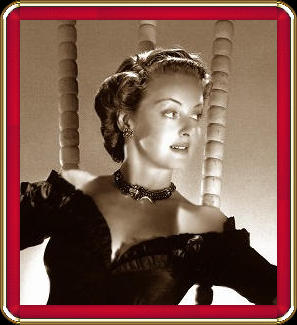

On her very first professional engagement with a stock company in Rochester, N.Y., she was fired by director George Cukor. In 1928 she appeared with the off-Broadway Provincetown Players and the following year made her Broadway debut in a domestic comedy, 'Broken Dishes.' Early in 1930, after a failed attempt at Goldwyn Studios, she was signed by Universal. It has been said that when the studio´s boss, Carl Laemmle, first saw her he commented that she had "as much sex appeal as Slim Summerville." She must have had enough sex appeal for bandleader Harmon Oscar "Ham" Nelson, who married Bette in 1932. For years she publicly fought the Motion Picture Academy, insisting that it was she who named their award statue after his second name. Apparently there was a striking resemblance between the statue's rearend, and her husband's. After appearing in a number of indifferent roles in routine productions, she attracted favorable attention as George Arliss's leading lady in The Man Who Played God (1932). This was the first of Miss Davis' long succession of films under a long-term contract with Warner Brothers. Gradually, her undeniable and forceful personality began showing in her roles. She had to fight for her right to play Mildred, the nasty, selfish waitress in John Cromwell's Of Human Bondage (1934). She was loaned-out to RKO for the occasion, and responded with the first of many electrifying performances, that were to evntually to make become known as "the first lady of the screen." Unfortunately, Warners continued offering her mediocre rolls in routine potboilers and soap operas. She made the best of them, as most serious actresses struggling for recognition did at that time. The Hollywood critics were consistently praising her acting, while panning the films. In 1935 she won her first Oscar for Dangerous, an inconsequential tearjerker. It was widely felt that winning that year was a consolation prize of sorts, for being snubbed by The Academy when she failed to receive a nomination for her performace in Of Human Bondage. Back at the studio, her vehicles continued to be of poor script quality. Bette, not shy or adverse to a fight, became rebellious. She refused another unsuitable role and was suspended without pay. She went England after accepting an offer to appear in a couple of European productions. Warners, to whom she was bound by contract until 1942, issued an injunction. Proving herself a formidable opponent, she promptly sued the company, but lost in the subsequent court battle. She may have publicly lost that battle, but the professional victory came with Warners treating her with greater respect and offering her roles that suited her powerful persona and obvious talent. Thus began the peak period of her career, with her appearance in a series of memorable films. First there was the fiery Southern belle in Jezebel (1938), for which she won her second Oscar. In 1939 alone, she appeared in four classic films: Dark Victory, Juarez, The Old Maid, and The Private Lives Of Elizabeth And Essex. During this decade Miss Davis gradually began developing an arsenal of personal screen mannerisms. Her acting style was increasingly more physical. Like a whirling dervish, she propelled herself through the roles in the films in which she appeared. Critics often found these broad affectations unnecessarily distracting, or downright disturbing. For most though, watching her in action on the big screen was, and still is a spellbinding experience. Her appeal to female audiences was definitely tied to her screen image as a willful, liberated woman who managed to remain spitefully independent in a world dominated by men. This was probably was not their reality, but they enjoyed seeing it portrayed none the less. Miss Davis also enjoyed a parallel support base amongst her gay fans, although she never really totally understood it. They admired her strong-willed defiance and tenacity in dealing with a world that was either unwilling, or unable to accept someone who refused to fit into a predescribed role and was truly different. Straight male audiences, for the most part, didn't know what to make of her. They were less responsive, or even threatened by the actress and her onscreen personae. There was probably a lot of fear in any kind of validation of this women who so brazenly upset the natural order of things. Moviegoers of the era were not used to seeing an actress so willing to play overtly ambitious women at their bitchiest, who proudly pursued their selfish goals at any cost. Davis probably derived much pleasure in going against this grain of 1930s sensiblity.

Ruth Elizabeth Davis, was born on April. 5, 1908, in Lowell, Mass. The daughter of a patent attorney and a portrait photographer who divorced when she was seven, she decided on an acting career while still a freshman at high school. After some light experience in school productions and in semiprofessional stock, she enrolled at John Murray Anderson´s drama school.