A brilliant navigator and a taciturn but determined leader, Ferdinand Magellan was born of a noble family in northern Portugal about the year 1480. Having served as a page in the royal court o f King John 11, he joined one of the annual Portuguese fleets to India. He took part in the seige of Malacca in 1511 as a captain of one of Alfonso d’Albuguerque’s ship. He befriended a Malay slave boy captured during the seige. Later he took the Malay slave boy back to Portugal and became his navigator because of his knowledge of the route to the Spice Islands and Nusantara. The Malay boy was given the name of Henry the Black or Enrique whose real name was Panglima Awang, who originates from Malacca. In fact it was Panglima Awang (Enrique) who taught Antonio Pigafetta the Malay language. Pigafetta manage to compile a list of 426 words, which was later made into the first Malay-Italian dictionary by Alessandrio Bausini. After eight years of soldiering in the Indies and Africa, he returned to Portugal, lamed by a wound received fighting the Moors in Morocco. Refused by King Manuel I Magellan turned to Spain and its young ruler Charles I, later emperor o f the Holy Roman Empire. Charles entrusted Magellan with a fleet of five ships to seek a westward passage to the Indies-the Portuguese dominated the eastern passage. Magellan had completed the most difficult part of his voyage when he was killed in a campaign against a native king at Mactan Island in the Philippines in 1521.

Beyond The New World: Magellan's Great Venture

One autumn day in 1516, a crippled soldier knelt awkwardly before his king, Manuel I of Portugal. The sovereign gazed with some distaste at the man, one Ferdinand Magellan. In recent years superior officers with whom Magellan had dared to disagree had been circulating malicious reports about his conduct. Yet there was no denying his noble birth, his brilliant military exploits, and his unswerving loyalty to the crown. Reluctantly, King Manuel nodded for him to speak.

Magellan announced that, at the age of 36, he was impoverished by eight years of navigating, exploring, and fighting battles for the crown in Africa and the Portuguese Indies. What was more, he had suffered three serious wounds in his majesty's service, including a lance wound in the knee that had left him permanently lame. He humbly begged an increase in his pension. Manuel, who was not by nature a rewarder, denied the request.

Surprised and hurt, Magellan remained on his knees. Then might he be granted command of a caravel to the Indies and perhaps restore his fortunes? No, said his majesty, there was no place at all for him in Portuguese service. The humiliated soldier could make only one final request: to be allowed to serve some other king. Manuel waved him away and snorted that he did not care in the least where Magellan went or what he did.

Bitterly humiliated, Magellan brooded over these harsh words for months. Gradually, he began to form a plan. For years his friend Francisco Serrano, who had settled in the Moluccas, had been urging Magellan to join him. These islands, lying just to the west of New Guinea, were also known as the Spice Islands, for they were the primary source of most of the spices that Europeans desperately coveted. And, Serrano added, the profits to be made in the spice trade were fabulous.

Eventually, Magellan wrote to his friend: "I will come to you soon, if not by way of Portugal, then by way of Spain." At the back of his mind as he penned those momentous words were recollections of maps and globes he had seen in the royal chartroom at Lisbon, as well as the widespread rumors that suggested the existence of an unexplored strait through the South American continent into Balboa's recently discovered "South Sea" (the Pacific). If he could discover the strait, he might open a western alternative to Portugal's lengthy-and fiercely defended-route around Africa and across the Indian Ocean to the Indies.

Fortunately for Magellan, several influential men in Spain were considering the same possibility. And Ferdinand Magellan, with his wealth of experience in the Indies, they all agreed, was just the man to carry out their plan. When they summoned him to Spain, Magellan left his native Portugal immediately.

In due course Magellan's backers arranged an audience with Spain's 17 year old King Charles I, who would have to approve the expedition. From the start everything went well. The youthful king was impressed by the limping veteran's passionate ambition, his geographical logic, and his personal knowledge of the Indies. Most likely, Magellan's past exploits and the drama of the proposed voyage itself also appealed to the young king's sense of adventure. In any case, he was well aware of the profits Spain could expect to reap if it broke the Portuguese monopoly of the spice trade by opening a new westward route to the Indies. On March 22, 1518, King Charles approved the financing of "a voyage to discover unknown lands" by way of the unexplored strait and appointed Magellan captain general of the expedition.

At Seville, preparations for the voyage took a full 18 months to complete. The long delay was partly the result of the machinations of King Manuel's consul at Seville. Although the expedition's destination was an official secret, Manuel's spies had found out the truth, and the king was determined to undermine this Spanish attempt to poach on the wealth of what he considered his personal realm in the Indies. Even more sinister were the plots of Don Juan de Fonseca, bishop of Burgos and counselor to the Spanish king, and German bankers who were financing the expedition. Appalled by the generous rewards King Charles had promised Magellan and fearing that the expedition was becoming too "Portuguese," they planned to limit Magellan's authority. In the course of several months of intrigue, Bishop Fonseca succeeded in having his illegitimate son, Juan de Cartagena, appointed captain of one of the ships (the others were commanded by Portuguese officers) and sympathetic Spaniards placed in a number of other key positions.

Through it all, Magellan worked methodically at the task of equipping his fleet for exploration. Five ships were purchased: the Trinidad (Magellan's flagship), the San Antonio, the Concepcion, the Victoria, and the Santiago. "They are very old and patched," the Portuguese consul wrote contemptuously to King Manuel, "and I would be sorry to sail even for the Canaries in them, for their ribs are as soft as butter." He did not realize that Magellan, who was as much a sailor as a soldier, was having the ships expertly reconstructed to withstand the hazards of the coming voyage.

One of the greatest problems was recruiting enough sailors to man the fleet. Haughty Castilian seamen were reluctant to serve under a foreign born commander. More important, the taciturn Magellan refused to say exactly where he was going, and professional mariners balked at signing up for a voyage of at least two years "to an unknown world." The only really willing recruit, in fact, seems to have been Antonio Pigafetta, a young Italian nobleman who wanted to see "the very great and awful things of the ocean." Secretly, he may also have been a spy for Venetian merchants interested in the spice trade. Whatever the case, history is in Pigafetta's debt. His lively, detailed diary is a firsthand account of Magellan's momentous voyage.

Despite the difficulties, the captain-general eventually managed to sign up a full complement of about 250 men, including Italians, Frenchmen, Germans, Flemings, Moors, and blacks, as well as Spaniards and Portuguese. He seemed confident that his iron personality would Weld this motley assembly into a disciplined corps of explorers.

On September 20, 1519, everything was finally ready. Cannon thundered and banners waved as the five ships glided out into the Atlantic from the port of San Lucar de Barrameda at the mouth of the Guadalquivir River. On September 26 they put in at the Canary Islands for last-minute supplies and fresh water. Within hours a packet followed them into port with an urgent letter for Magellan from friends in Spain. The message was ominous: It warned him of the plot of Cartagena and his henchmen to mutiny and murder their leader. Magellan coolly decided for the moment to do nothing more than watch Cartagena closely. He was confident that, when the time came, his military training would be more than a match for any insubordination.

A few days later the little armada headed south along him to mind his own business and follow orders. the coast of Africa. Magellan's sailing orders were After enduring violent storms off the coast of Sierra characteristically terse: "Follow my flag by day and my Leone, the fleet finally altered course and headed lantern by night." Silently limping to and fro on the southwest, but was soon becalmed in the equatorial quarterdeck of the Trinidad, he divided his attention doldrums. For three weeks the ships lolled idly on the between the empty ocean up ahead and the four ships glassy sea. Tar melted, timbers split in the baking heat, foaming along behind him. Every evening at sunset he and the men began to grumble about the futility of the had his captains draw near the flagship and shout the voyage. But the little captain-general remained traditional greeting: "God save you, Sir Captain-General and Master and good ship's company." By this simple procedure Magellan regularly reminded every man in the expedition of his absolute authority

Chafing with resentment, Cartagena waited for a chance to challenge the captain-general. It came when Magellan, true to his Portuguese training, followed Da Gama's course and hugged the bulge of Africa for a while before heading west across the Atlantic. Cartagena asked sharply why the expedition was not following a diagonal "Spanish course" to the southwest. He was stunned by the response. Magellan simply warned him to mind his own business and follow orders.

After enduring violent storms off the coast of Sierra Leone, the fleet finally altered course and headed southwest, but soon becalmed in the equatorial doldrums. For three weeks the ships lolled idly on the glassy sea. Tar melted, timber split in the baking heat, and the men began to grumble about the futility of the voyage. But the little captain general remained wrapped in a private cocoon of silence.

Some time after the wind returned and the ships resumed their journey (reports on the incident are. vague and contradictory), Cartagena again challenged Magellan's authority. One evening, instead of per sonally calling out the customary salute, he turned the duty over to his boatswain, who rudely addressed the captain-general simply as "captain." Magellan sharply upbraided the sailor but took no immediate action against Cartagena. Three days later, however, in a face-to-face confrontation, Cartagena abruptly announced that he would no longer obey Magellan's orders. This was an act of open mutiny-exactly what Magellan had been waiting for. Grabbing Cartagena by the shirtfront, he icily declared that the Spaniard was his prisoner. The rebel was placed in custody of another officer, and that evening a new captain shouted obeisance in his stead.

Favorable winds now blew the ships steadily across the Atlantic, and before long the shores of Brazil were sighted. Sailing south past jungle-clad coasts, the fleet finally dropped anchor in mid-December. in the spectacular bay that would in time become the site of Rio de Janeiro. There Magellan allowed his weary sailors two idyllic weeks ashore.

The local Indians, Pigafetta noted, were cannibals. Fortunately for the Europeans, they were greeted as gods and regaled with banquets of suckling pig and fresh pineapples-certainly a welcome change from pickled pork and ship biscuit. There was also much delighted chasing of Indian girls who wore no clothes and whose parents were more than willing to give them up as slaves in exchange for a knife or an ax.e.

Magellan, who had recently married a Spanish woman, remained aloof from the revels until the time came to drag his reluctant men back to their duties.

There were fouled water casks to scour and refill, worn timbers to repair, torn sails to stitch. On December 27, to the tearful farewells of native girls, the captain-general ordered his men to weigh anchor and continue souuth in search of the strait.

New Year's Day 1520 passed almost unnoticed as the explorers scanned Brazil's impenetrable coast for any sign of the strait. Hopes soared when, after two weeks and more than 1,200 miles of sailing, they discovered a broad westward channel at just about the latitude where all the charts indicated the strait would be. But the channel rapidly narrowed to nothing more than a river, the modern-day Rio de la Plata.

Bitterly disappointed, Magellan concluded that the charts were wrong. The strait had to be farther south in the frozen regions of Terra Australis, the legendary landmass presumed to exist at the bottom of the globe. Many sailors were so discouraged they wanted to turn back, but Magellan's iron will and contempt for cowardice drove them on. Sailing headlong into the approaching autumn and winter of the Southern Hemisphere, the five ships were beaten by brutal seas, violent winds, and persistent hailstorms. Ice began to clog the rigging faster than the sailors could hack it away. The captain-general himself slept no more than a couple of hours at a time and, like the rest of the crew, ate not even one hot meal for weeks on end. "The fool is leading us to destruction," Cartagena is said to have muttered. "He is obsessed with his search for the strait. On the flame of his ambition he will crucify us all."

At the end of March, Magellan took pity on his frozen crew and decided to winter ashore. The fleet anchored in a forbidding but sheltered bay he named Port St. Julian, near the southern tip of Argentina. There were no friendly welcoming natives: only gray cliffs and desolate beaches. A mood of general depression settled down like a fog. After six months at sea the explorers had reached nowhere, found nothing. Of what use was this sterile coast to Spain? they asked. Where was this imaginary strait to the Spice Islands?

The captains pleaded with Magellan to return home or at least go back to the milder latitudes of Rio de la Plata for the winter, but Magellan stubbornly "refused even to discuss the matter." In no time at all the mutiny he had so long expected broke out. According to Pigafetta, the ringleader in the plot was Juan de Cartagena. Gaining control of three ships, he apparently planned to make a dash for the harbor entrance and head for Spain, but he proved no match for Magellan. Slipping some of his own men aboard one of the mutineers' ships, Magellan quickly took possession of her and with three ships formed a blockade across the harbor's mouth and regained control of all five of his ships.

Magellan immediately court-martialed the leaders of the plot, and they were found guilty of mutiny. Then, displaying a grim sense of drama, he staged a ritual execution against a background of jagged rocks in the presence of officers and men. One of the mutinous captains was led to the block, where his own servant cut off his head. His body and that of another captain who had been killed in the fighting were drawn and quartered, and the pieces hung from four gibbets erected on the shores of the bay. Magellan's authority was reestablished beyond question. As for Cartagena, he and a mutinous priest would be marooned when the fleet eventually left the desolate bay.

The fleet was at Port St. Julian for two months before the Europeans saw any natives. Then, "One day, suddenly we saw a naked man of giant stature on the shore of the harbor, dancing, singing, and throwing dust on his head . . . ." This strange creature, with hair painted white and face daubed with red and yellow, Pigafetta added, "was so tall that we reached only to his waist."

The first giant soon was followed by others, who became friendly with the explorers and went so far as to dance with them, leaving footprints four inches deep in the sand. The skins they wrapped around their feet were apparently packed with dry grass for added warmth. Consequently, Magellan called the giants Patagones (Spanish and Portuguese for "big feet"), and the name of their country soon became Patagonia.

Anxious to continue his exploration, Magellan now sent the Santiago south to reconnoiter the coast. The ship was wrecked in a storm-fortunately with only one life lost-but the survivors reported the discovery of a much more favorable harbor. So, after five months in their grim anchorage at Port St. Julian, the four remaining ships set sail late in August for their new port, where they remained until October 18.

By then, spring in the Southern Hemisphere was fast approaching, and Magellan was eager to resume his search for the elusive strait. Three days later and about 100 miles farther south, the fleet rounded a sandy headland and found yet another vast bay. The captains protested that it was useless to waste time exploring there: There could be no strait through the bay's western end. But the captain-general would not pass by any possibility. He ordered the captains of the Concepcion and San Antonio to seek a western outlet in the bay.

A sudden storm swept the two ships out of sight behind a rocky promontory jutting into the bay, and for two days rough weather prevented Magellan from following. When he finally was able to round the headland himself, the two lost ships soon reappeared, with flags waving and cannon booming. Clearly, they had good news to report, but with his usual self-control, the captain-general neither laughed nor shouted. He simply bowed his head and crossed himself. Soon the San Antonio drew near enough for her captain to announce joyfully that the ships had sailed more than 100 miles into a deep narrow channel with strong tides and no sign of fresh water. This was no mere river mouth-it had to be the strait to the great South Sea.

The fleet then sailed majestically west into an awesome passage between towering mountains. "And they thought that there was no better nor more beautiful strait in the world than this one," Pigafetta declared enthusiastically. The Strait of All Saints, as the captain-general called it-it now rightfully bears his own name-proved to be no ordinary channel. Varying from 2 to 20 miles in width, it is a watery labyrinth that veers and twists and fans out into countless false bays and narrows. Except for a group of huts filled with mummified corpses and a brief visit by a boatload of natives that disappeared mysteriously in the night, the explorers saw few signs of human life. Yet later in the passage they saw many lights of campfires twinkling and glowing to the south. Magellan accordingly named the place Tierra del Fuego, "Land of Fire," and so the vast island south of the strait is called to this day.

Coming upon a large island in the channel, Magellan ordered the captain of his biggest ship, the San Antonio, to explore its southern side while the rest of the fleet continued along the north shore. Soon they found a good anchorage at the mouth of a river teeming with sardines. Magellan set his crew to work salting down a supply of the fish. Then, instead of risking a ship in the unexplored waters ahead, he sent some sailors in a longboat to search for an outlet to the sea. A few days later the boat returned, with its crew screaming, "We found it! We found it!" The news about the outlet so overwhelmed Magellan that, according to Pigafetta, the iron man actually cried.

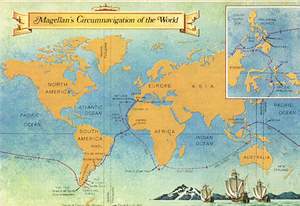

But the San Antonio did not return. Fearing that she had been wrecked, Magellan wasted almost three weeks vainly searching for her, until the bitter truth dawned that the crew had deserted and returned to Spain-along with a great share of the fleet's scant provisions. Although this catastrophe left Magellan dangerously low on supplies, he resolved to sail on west through the mists, turns, and seething waters of the strait. Finally, on November 28, the three ships sailed out of the 310-mile-long channel and into a wide and peaceful ocean. After an appropriate ceremony of thanksgiving, Magellan announced to his officers: "Gentlemen, we now are steering into waters where no ship has sailed before. May we always find them as peaceful as they are this morning. In this hope I shall name this sea the Mar Pacffico."

Instead of sailing boldly northwest into the great blank of the Pacific Ocean, Magellan began to sail north for a while, parallel to the coast of present-day Chile. Although this course was only postponing the agony of finally entering the void, it did bring one welcome bonus: warmth. Magellan's weary sailors, who had been shivering ever since their arrival at Port St. Julian over eight months before, rejoiced as sun and milder air began to caress their skins.

The ships foamed steadily north for almost three weeks before Magellan, worried about his dwindling supplies, issued the momentous order: "Northwest!" The signal passed from ship to ship; three tillers swung to starboard; and the fleet moved out into the open Pacific. Magellan had no way of knowing that his course would bypass most of the islands that dot the mid-Pacific or that an ocean covering one-third of the earth's surface still separated him from the Moluccas.

As 1520 passed unobtrusively into 1521, day after day, week after week, lookouts hopefully scanned the horizon. But the expected islands did not appear. All sense of progress was lost; the three ships seemed to be wallowing in a vast unchanging disk of blue water with no end in sight.

The threat of starvation soon became horrifying reality. Pigafetta vividly recalled: "They ate biscuit, and when there was no more of that they ate the crumbs, which were full of maggots and smelled strongly of mouse urine. They drank yellow water, already several days putrid. And they ate some of the hides that were on the largest shroud to keep it from breaking .... They softened them in the sea for four or five days, and then they put them in a pot over the fire and ate them and also much sawdust." In time the starving, scurvywracked sailors were reduced to vying with each other for rats caught in the hold.

The suffering of his men opened an unsuspected reservoir of compassion in Magellan. Every morning he would limp from victim to victim, nursing those who had escaped death in the night. Pigafetta noted with admiration that the captain-general "never complained, never sank into despair."

Mercifully, on January 24, after nearly two months of sailing without sight of land, a tiny uninhabited atoll appeared on the horizon. There the famished sailors gorged on sea birds and turtle eggs and replenished their supply of drinking water. A couple of weeks later another small island was sighted, but the wind swept the fleet helplessly past it.

The weeks continued to drag by. On March 4-the 97th day of the voyage across the Pacific-the men on the Trinidad ate their last scrap of food. Two days later one of the few men still strong enough to climb the rigging screamed hoarsely from the crow's nest: "Praise God! Land! Land! Land!"

The little fleet had hardly dropped anchors off the island now called Guam when Magellan was greeted by a flotilla of outrigger canoes full of excited, light fingered natives who rushed on board and carried oil everything they could lay their hands on. The pilferage continued until some maddened sailors fired their crossbows. Magellan contemptuously named his discovery the Isle of Thieves.

.Keeping the islanders at bay by the simple technique of setting their huts on fire, the captain-general managed to send a land party ashore to do some looting of its own. The Europeans helped themselves to the natives' water and the fresh food that the scurvy victims craved, then enjoyed an orgy of feasting on roast pork, chicken, rice, yams, bananas, and coconuts. A few days later they paused at another island for more provisions-this time obtained by barter-and before long the ravaged sailors' health began to return. Ulcers healed; loose teeth became firm; swollen gums slowly began to recede.

With bodies strengthened and morale restored, the explorers sailed on to the west. On March 16 yet another large island came into view, and in the days that followed more and more islands appeared on the horizon. Magellan gradually realized he had stumbled upon a huge unknown archipelago. It was the Philippine Islands. Although no spices grew there, the islanders had plenty of gold and pearls. In time, a valuable transpacific trade would develop between the islands and Spanish ports on the western coasts of Central and South America.

While anchored off one of the islands, Magellan received dramatic proof that he had practically circumnavigated the globe. When a canoe full of islanders put out from shore, Black Enrique, the captain-general's slave since his youthful days in the Far East, hailed the natives in Malay, the language used throughout the Indies. The islanders understood and responded in Malay. Magellan had left the East Indies eight years before, in 1513. Now, after continuously moving away from them, he was again drawing near.

This supreme moment in the captain-general's life seems to have had an extraordinary effect on him. Always deeply religious, he became obsessed with missionary zeal. Postponing the final stage of his voyage to the Moluccas, he put in at the large island of' Cebu, improvised an altar on shore, and began to preach to crowds of fascinated natives. "The Captain told them they should not become Christians out of' fear," reported Pigafetta, "nor to please them, but voluntarily." His sermons, interpreted by Black Enrique, must have been extremely effective. On a single Sunday, April 14, Magellan baptized dozens of local chieftains, including the rajah of Cebu himself, as well as hundreds of ordinary citizens. A "holy alliance" was then negotiated with the rajah, effectively establishing the authority of Spain over the Philippines.

Only one chief, a ruler on the tiny island of Mactan, balked against Magellan's peaceful conquest. Intoxicated by his evangelistic and political success, the captain-general threw aside his customary caution. Hastily crowding 50 or so volunteers into three small boats, he set oil' on a foolhardy attempt to force compliance upon the island.

On April 27, 1521, the little Christian army waded ashore on Mactan Island. Hundreds of' warriors awaited them, massed behind a series of deep, defensive trenches. Even with their arquebuses, crossbows, and steel armor, the Europeans were no match for the horde of shrieking Filipinos that let loose volleys of "arrows, javelins, lances with points hardened in the fire, stones, and even filth, so that we were scarcely able to defend ourselves." Before long the Christians were fleeing headlong for their boats. Bringing up the rear were the limping captain-general, by now wounded by an arrow in his leg, and a handful of soldiers. For an Dour the little band fought desperately at the water's cdge, reported Pigafetta, "until at length an islander Succeeded in wounding the Captain in the face with a bamboo spear. He, being desperate, plunged his lance into the Indian's breast, leaving it there. But, wishing to use his sword, he could draw it only hallway from the sheath, on account of a spear wound he had received in the right arm .... Then the Indians threw themselves upon him, with spears and scimitars and every weapon they had, and ran him through-our mirror, our light our comforter, our true guide-until they killed him."

After the death of Magellan, relations between the explorers and their hosts on Cebu deteriorated rapidly. Suddenly, men with white skins seemed less godlike, more vulnerable. The rajah, goaded by a disgruntled member of the expedition, suspected the Spanish expedition of treachery. On May 1 he invited 27 officers of the fleet to a banquet, encouraged them to eat their fill, and then had most of them slaughtered.

This catastrophe reduced to 114 the manpower of an expedition that, at the outset, had numbered some 250 men. There were now too few sailors to man three ships; so hastily stripping and burning the Concepcion, the survivors consolidated themselves in the Trinidad and Victoria and fled from Cebu.

Bereft of Magellan's leadership, the two ships wandered aimlessly about the South China and Sulu Seas for six months, committing random piracies on local traders, before happening on the island of Tidore in the Moluccas. There they loaded up with such a heavy cargo of spices, especially cloves, that the Trinidad began to split along the seams. Leaving her behind for repairs (she was later captured by the Portuguese and only a handful of 'tier crew ever returned to Spain), the Victoria, under the command of Juan Sebastian del Cano, sailed southwestward into the Indian Ocean in December 1521.

The long voyage home was not a happy one. Del Cano, who had been involved in the mutiny at Port St. Julian, proved to be an unpopular captain. There were petty mutinies and desertions en route. Storms impeded progress around the Cape of Good Hope. While sailing up the west coast of Africa, sailors continued to die of scurvy and starvation. It was not until September 8, 1522, almost exactly three years since her departure from Spain, that the Victoria creaked wearily into Seville's harbor. A silent crowd watched in amazement as only 18 survivors staggered ashore. Gaunt and barefooted, the next day they carried lighted candles to give thanks at Magellan's favorite shrine in the church of Santa Maria de la Victoria.

Having thus honored his dead leader, Del Cano accepted from King Charles the ultimate reward of the expedition: a coat of arms depicting the globe and bearing the motto Primus circumdedisti me, "You first circumnavigated me." Yet historians have never been able to decide which man rightfully deserves that honor. Was it Magellan who, some say, had already visited the East Indies as a youth? Was it his humble slave Black Enrique? Or was it Del Cano? But the loyal Antonio Pigafetta, who survived to write the story of the voyage, had no doubts. Of Magellan he stated flatly: "The best proof of his genius is that he circumnavigated the world, none having preceded him."

Source: Discovery-The World's Greatest Explorer:Their Triumph and Tragedy by Readers Digest.

| Introduction | History-Dates and Events | Historical Places In Malacca | Interesting Places To Visit In Malacca | Walk About | Trivia and Folklore | Old Paintings and Maps | The Malay Sultanate of Malacca | Legendary Visitors Of Malacca | The Portuguese Conquest | The Malacca Fort | The Ruins of St Paul's Church | Getting There | Where To Stay | Maps | University Tenaga Nasional | Who Am I | Search | Today's Weather Report

Back to Robert K.H. Leo's Homepage

FastCounter by bCentral