This web page is still in editing mode, and is not finished.......... More information is to be inputed also, so please bare with me.

GO DOWN PLEASE!

--- ========================= Click Here! ========================= ---

DEPRESSION

DEPRESSION

--- ========================= Click Here! ========================= ---

DEPRESSION

DEPRESSION

Click! Below! To See Stats For This Entire Website DataBase!

Check Page View Stats Etc... for The Entire 1-43 Pages!!!

|

flame. Counter Manager

DEPRESSION

(*Counter* - Started on: 18 Sep, 2013.)

Clause -- - The following statements are mostly direct quotes that I have taken from books and other noted sources. I have not attempted to put them in my own words yet because I'm not a layman in writing. Plus, I feel it would only detract from the effectiveness of the statements. I will, perhaps, do this at a later date if desired.

Treatment of the Obsessive Personality

"Leon Salzman, M.D."

Copyright 1985, 1980

Freud's formulation was related to the libido theory and stated that depression was the result of the loss of an ambivalent loved object. He felt that the individual introjected the lost object and that the hostility manifested in this disorder resulted from the expression of the person's feeling toward the hated aspects of the lost object. This interpretation was useful in explaining many observable manifestations of the depressive reaction, both neurotic and psychotic. It emphasized the elements of hostility and the loss of a valued object, which resembled the process of mourning.

The concept of depression presented here proposes that depression is a reaction to a loss and a maladaptive response in attempting to repair the loss. It is not seen as a disease but as a potential in all personality structures when a loss is experienced as leaving one totoally helpless and impotent. It is in this respect that its relationship to the obsessional mechanism is manifested, and it is under these circumstances that the obsessional mechanisms break down because of internal or external stresses.

A variety of defensive responses may occur in the wake of a failing obsessional defense - for example, schizophrenia, paranoid developments, and other grandiose states, as well as depression. At present it is extremely difficult to determine why one response occurs and not another. However, it is clear that the depressive reaction is commonplace because the obsessional mode of behavior is universal. The depressive reaction may be mild or severe, with the same wide spectrum. When it occurs in the normal obsessional or in those with any other neurotic disorder or personality type, it is the failure of the obsessional defense to maintain the standards or values considered by the individual to be essential. Depression follows the conviction or apprehension that the value, person, or thing deemed necessary may actually be lost or no longer available.

These values or persons are not necessarily realistic nor are the demands reasonable. They are invariably extreme and excessive and form part of the obsessive neurotic value system in which the requirements for perfection and omniscience are essential ingredients. While the obsessional system is intact, the illusion of omniscience and perfection can be maintained. However, a crises, or some unexpected event may stir up the individual's apprehension about his ability to maintain these standards. If the concerns continue and the apprehension becomes a conviction, depression may supervene.

From the adaptational point of view (without recourse to earlier theories), depression is a reparative process which supervenes when a person feels he has lost something vital to his phychic integration. The reaction of despair and depression is the result of the anticipated rebuff and the expectation of total rejection as a consequence of this loss. With this framework in mind, the other elements in depression become more understandable. The hostile, demanding, and clinging behavior is related to this desperate attempt to regain the lost object from those felt to be responsible for taking it away or capable of restoring it. The depressed person pleads, begs, demands, cajoles, and attempts to force the environment to replace or restore the object.

If depression is related to the obsessive dynamism, the responsiveness of depressions to physiological therapies must also be accounted for. Because electric shock therapy and drug convulsants produced effects which either injured the patient or made him fearfully resistive, he viewed such treatment as punishment. This attitude coincided with the theory of depression which implied that such people are guilty and self-destructive. Shock therapy was viewed as relieving the superego of its harshness, permitting the depression to be resolved. This is an appealing view, even though the insulin therapies (unlike metrazol and ECT) are neither painful nor distressing. Too, the use of tranquilizers, psychic energizers, and placebos - which produce little or no distress yet prove valuable - casts serious doubts on such an interpretation. It has never been clearly established where the value of such dissimilar physiological approaches lies. The tranquilizing drugs, with their mildly euphoric effect. and the psychic energizers, which improve the patient's physical condition, are also beneficial in the treatment of depressive states.

Concise Guide to Mood Disorders

Steven L. Dubovsky, M.D.

Amelia N. Dubovsky, B.A.

Unipolar and Bipolar Mood Disorders

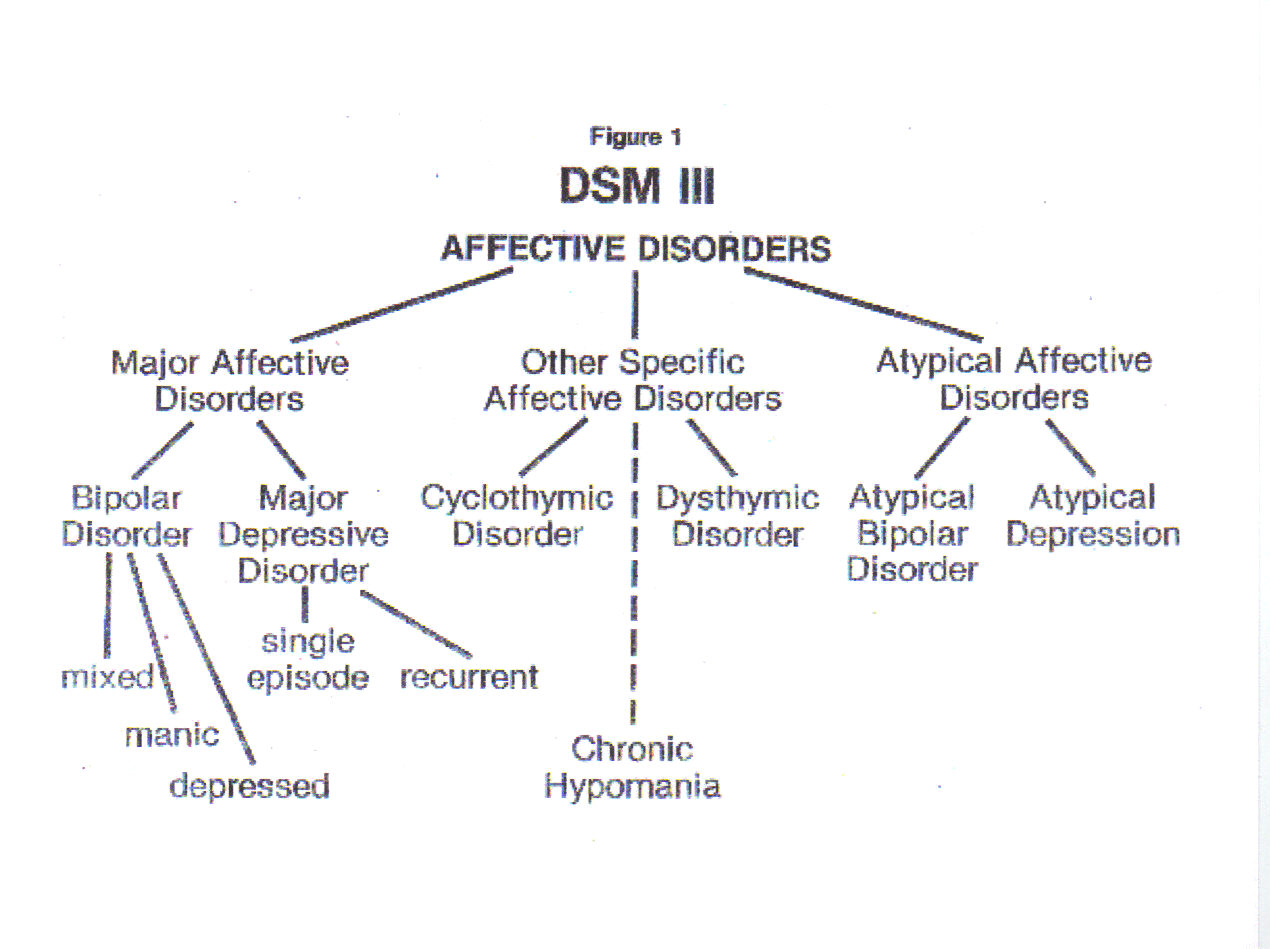

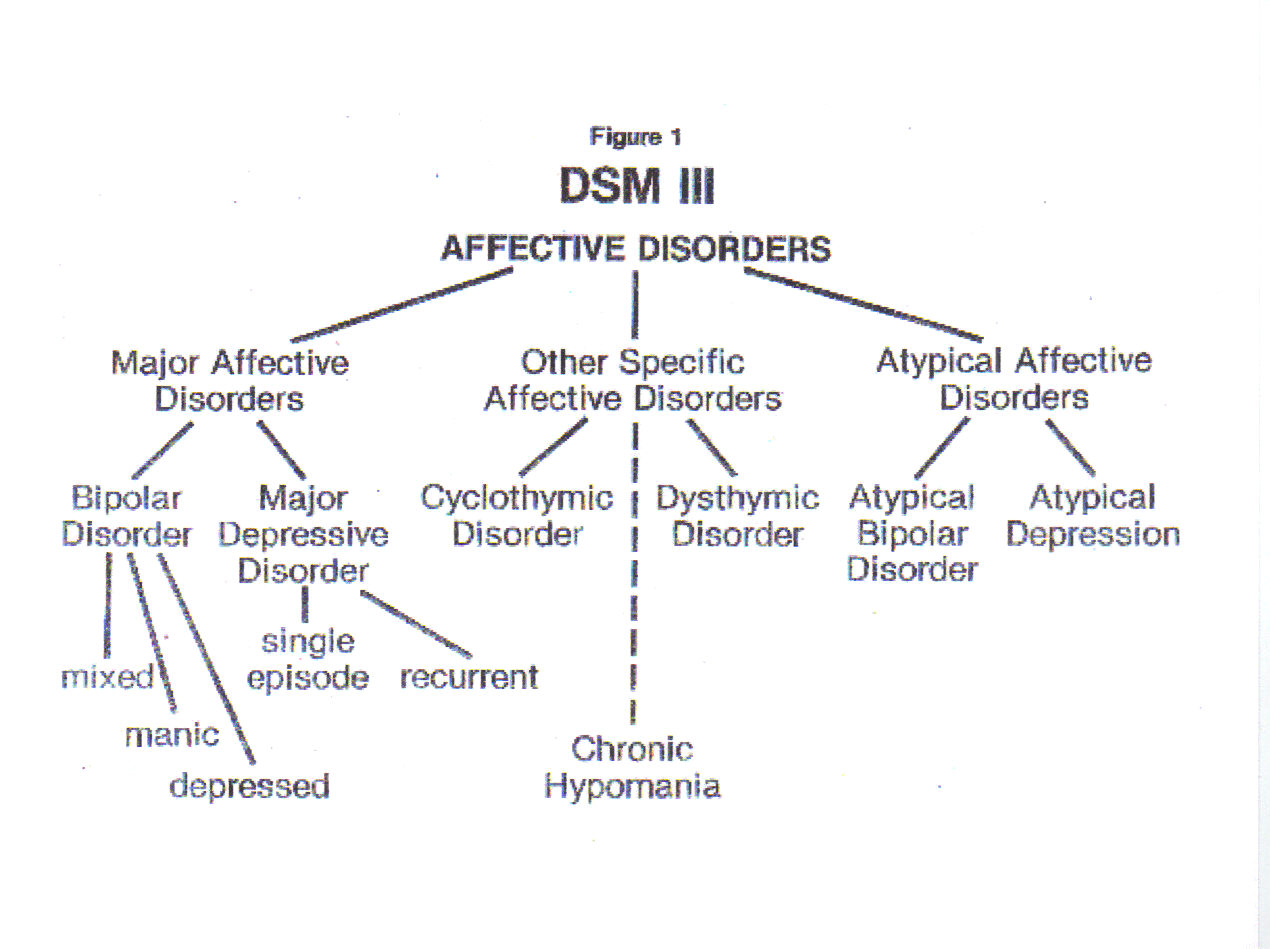

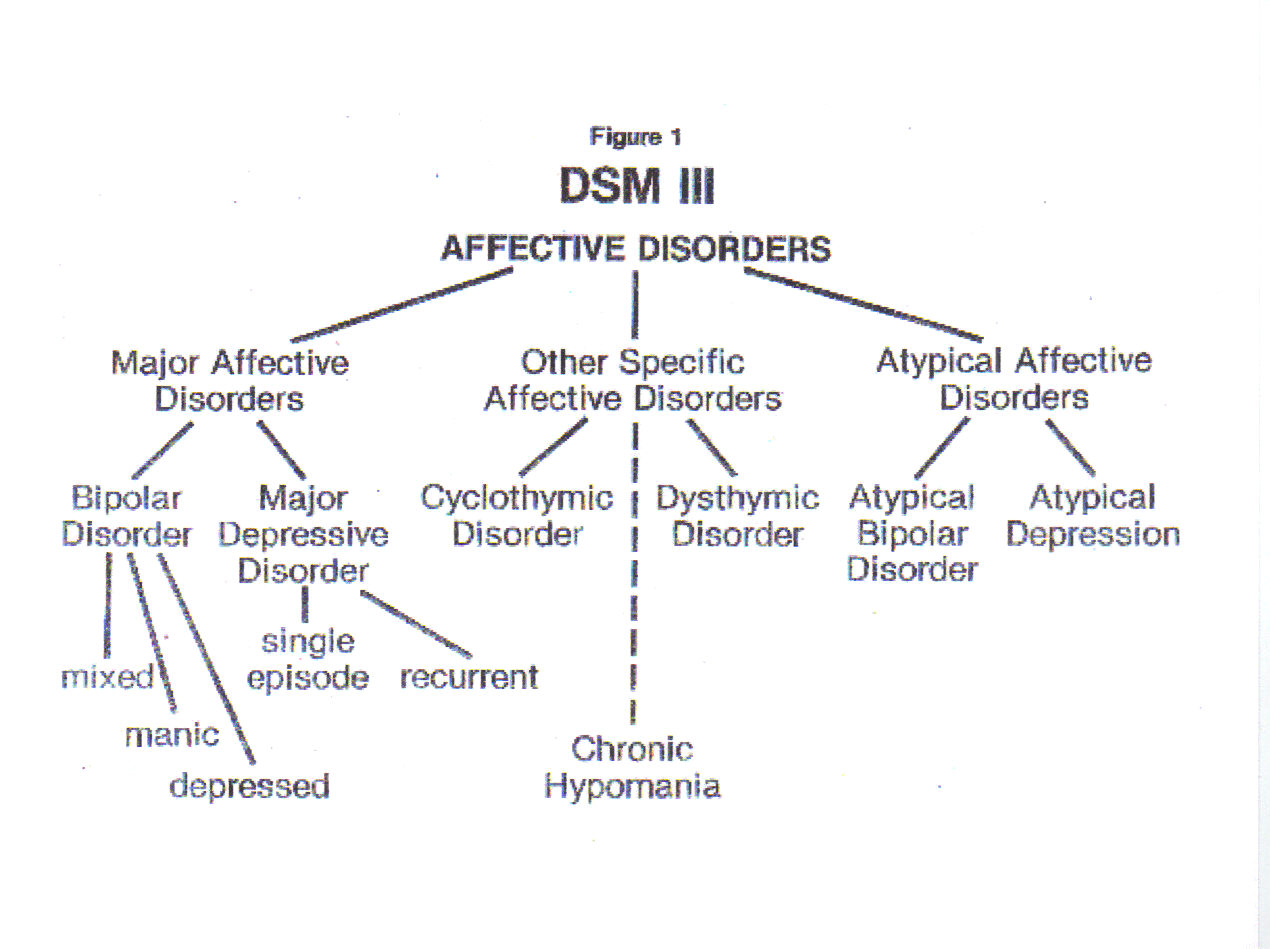

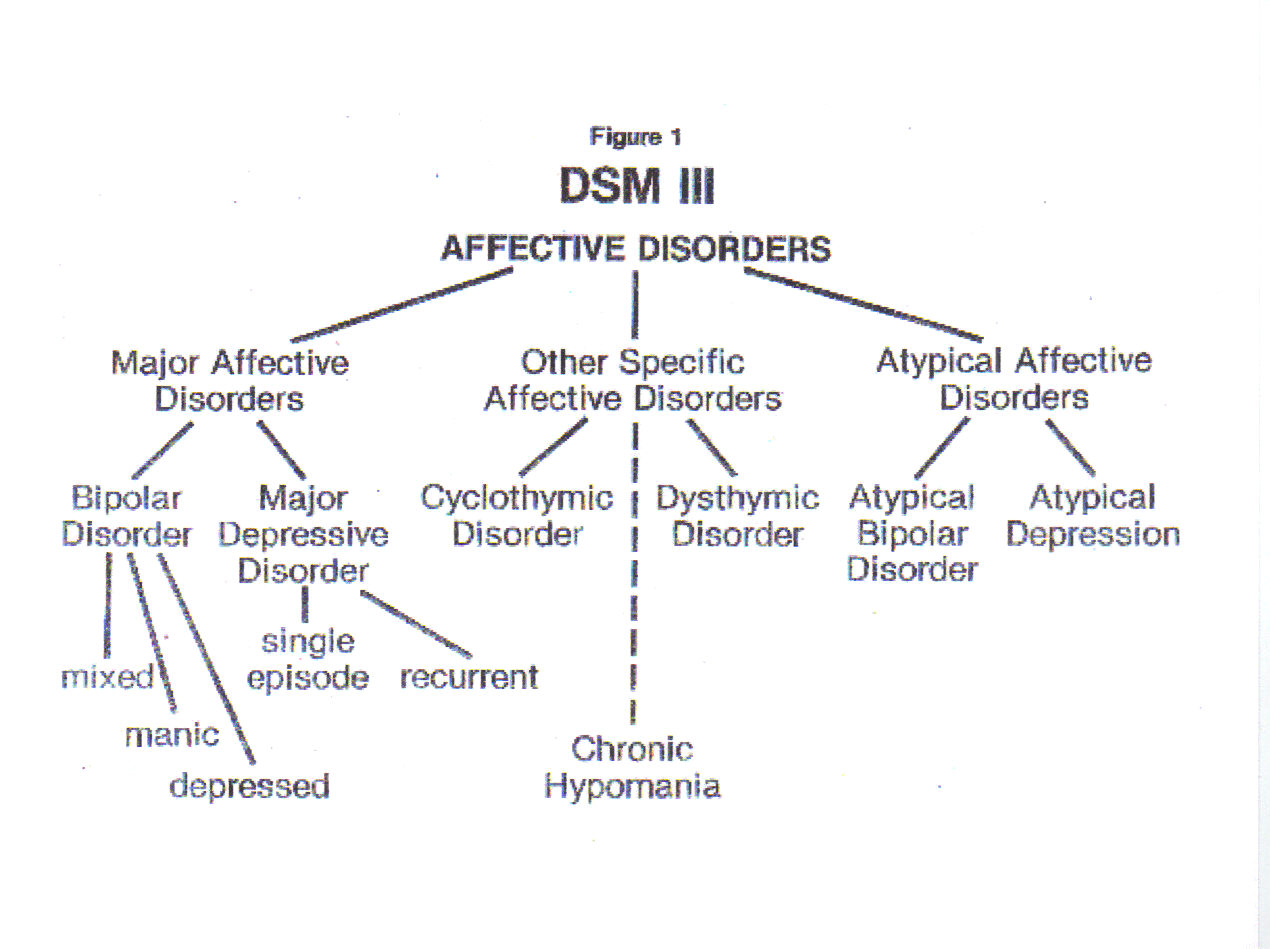

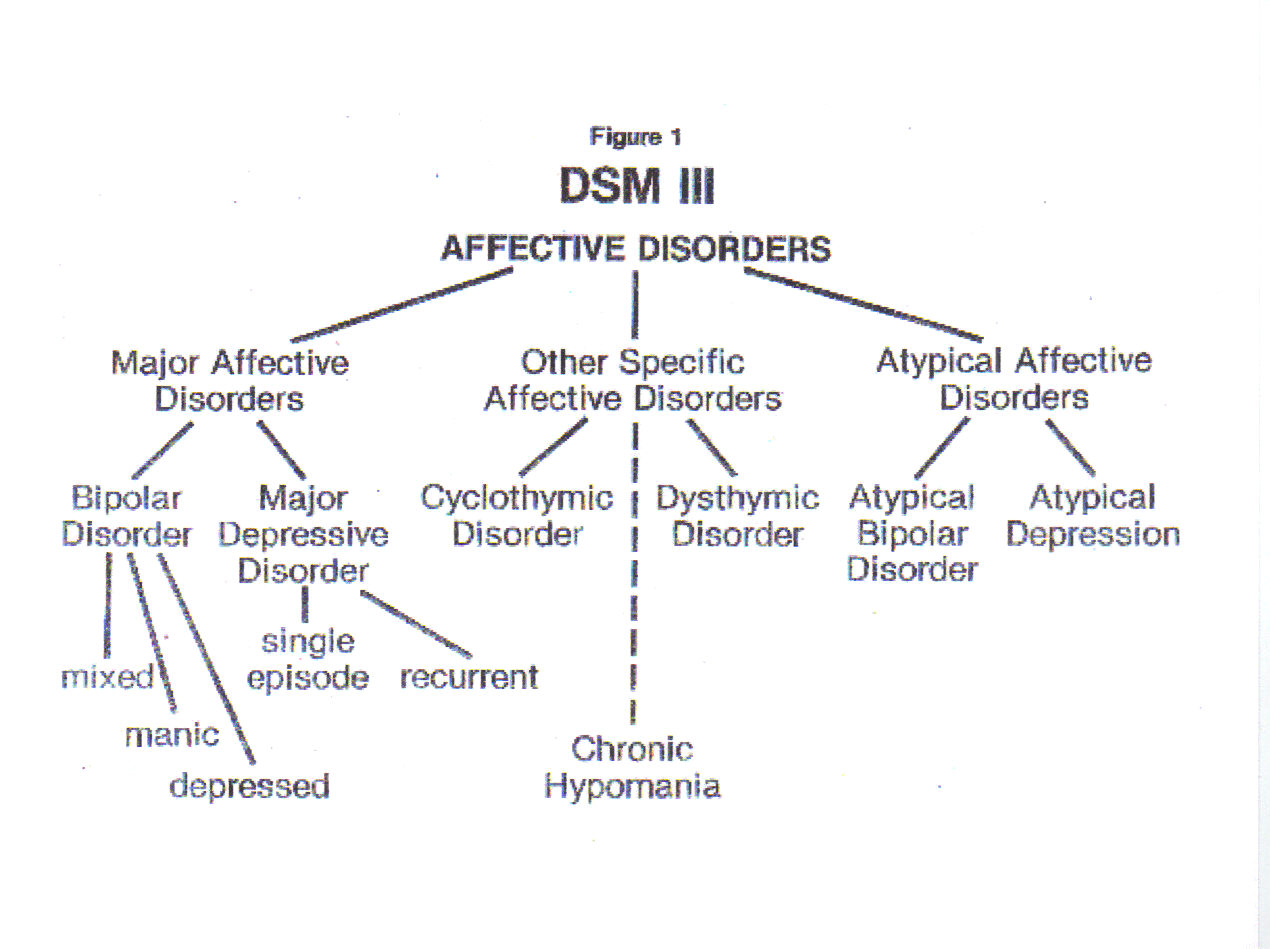

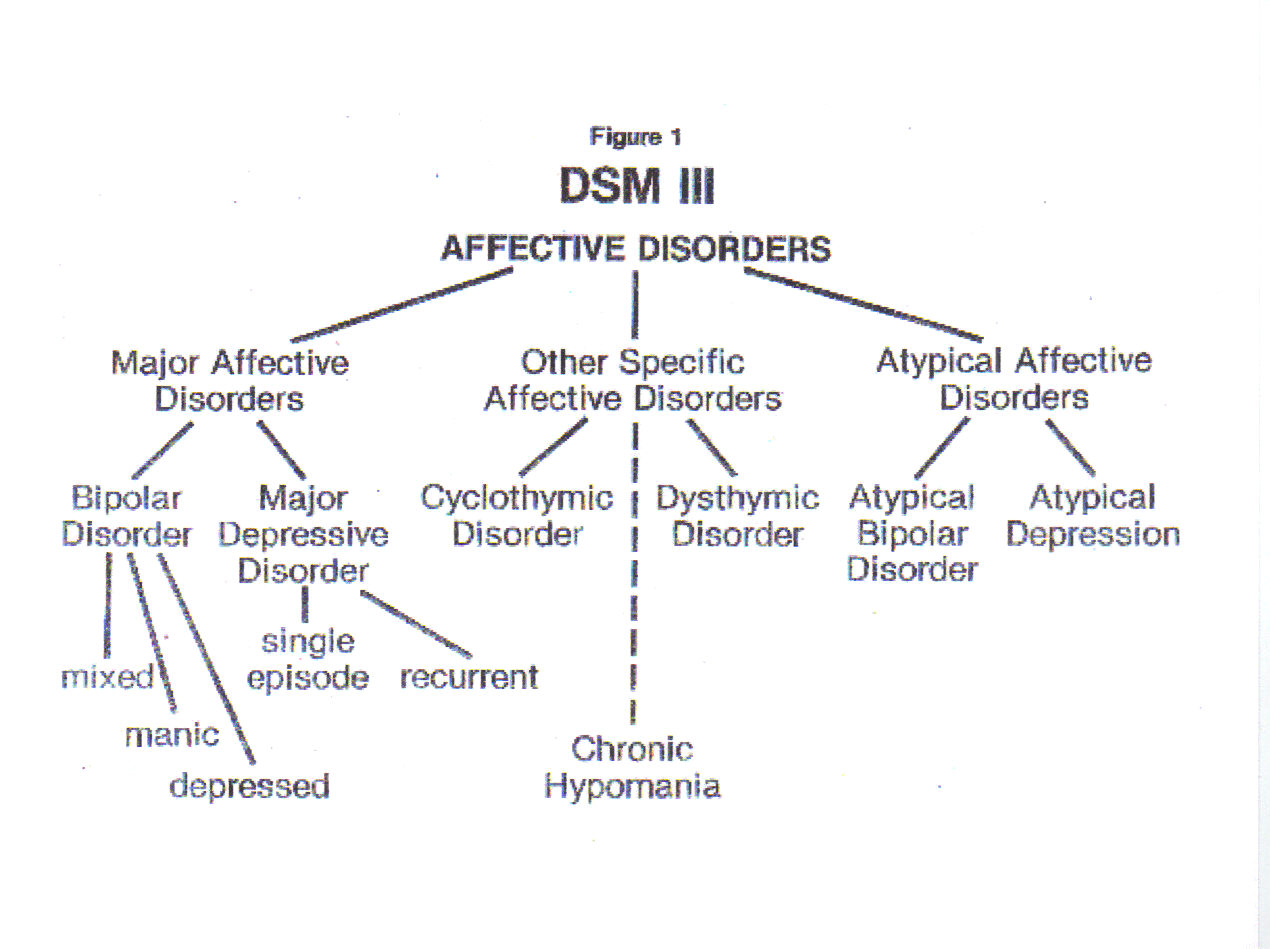

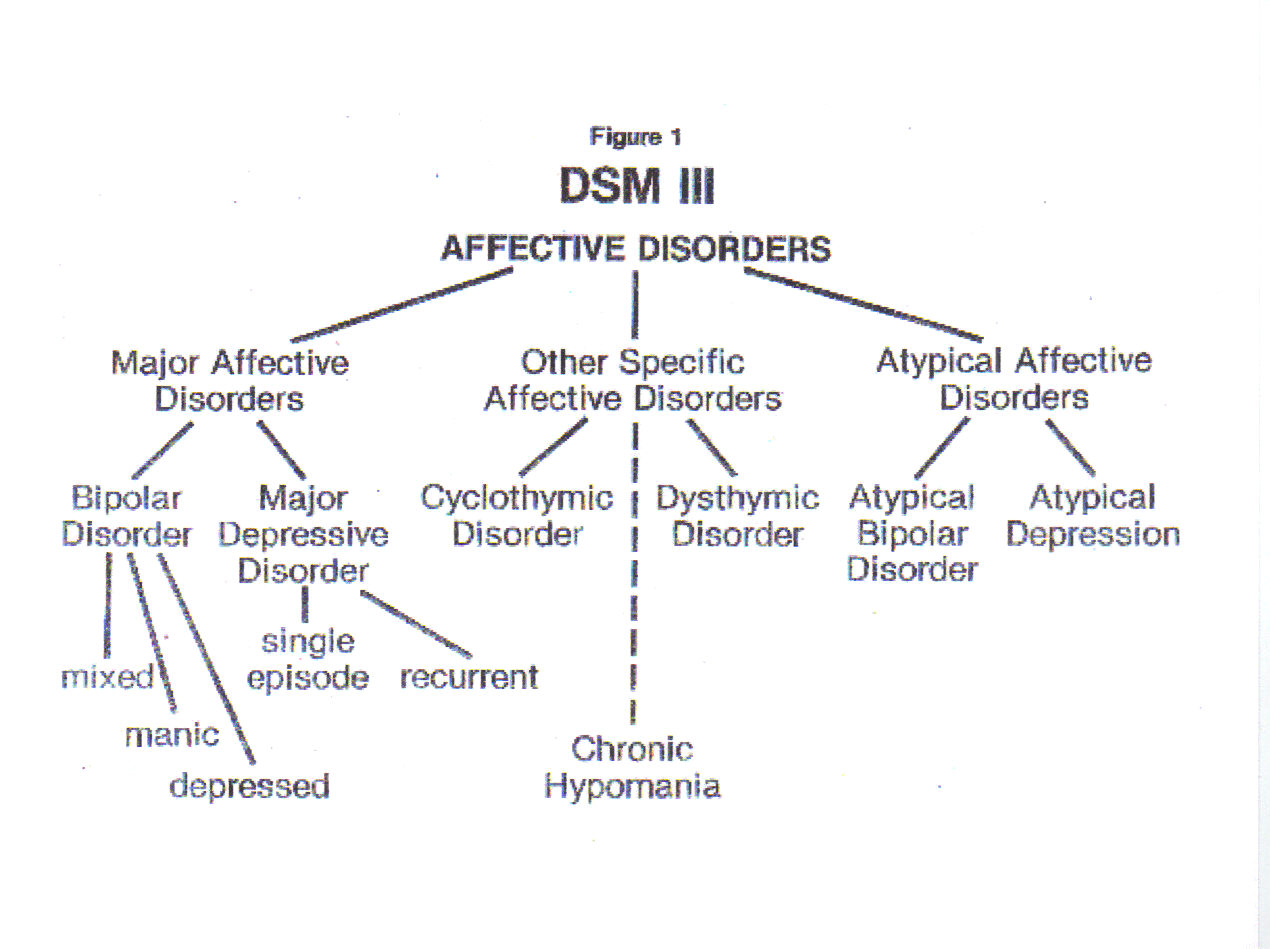

One of the most important distinctions between mood disorders is the distinction between unipolar and bipolar categories. Unipolar mood disorders are characterized by depressive symptoms in the absence of a history of a pathologically elevated mood. In bipolar mood disorders, depression alternates or is mixed with mania ("unipolar mania") are given the diagnosis of bipolar mood disorder, on the assumption that they will eventually have an episode of depression.

Understanding Depression

Patricia Ainsworth, M.D.

Symptoms of Depression

There is no blood test for depression yet. The diagnosis is based on the reports of sufferers about how they feel and on observations of how they look and behave made by doctors and by people who know them well.

The symptoms of depression fall into four categories: mood, cognitive, behavioral, and physical. In other words, depression affects how individuals feel, think, and behave as well as how their bodies work. People with depression may experience symptoms in any or all of the categories, depending on personal characteristics and the severity and type of depression.

Depressed people generally describe their mood as sad, depressed, anxious, or flat. Victims of depression often report additional feelings of emptiness, hopelessness, pessimism, uselessness, worthlessness, helplessness, unreasonable guilt, and profound apathy. Their self-esteem is usually low, and they may feel overwhelmed, restless, or irritable. Loss of interest in activities previously enjoyed is common and is usually accompanied by a diminished ability to feel pleasure, even in sexual activity.

As the illness worsens, the cognitive ability of the brain is affected. Slowed thinking, difficulty with concentration, memory lapses, and problems with decision making become obvious. Those losses lead to frustration and further aggravate the person's mounting sense of being overwhelmed. The sufferer longs for escape, and thoughts of death intrude, sometimes taking the form of wishful thinking, as in "I wish God would just take me" or "I wish I could vanish," and often involving ideas of suicide.

In its most severe forms, depression causes major abnormalities in the way sufferers see the world around them. They may become psychotic, believing things that are not true or seeing and hearing imaginary people or objects.

Psychosis in depression is not rare. between 10 and 25 percent of patients hospitalized for serious depression, especially elderly patients, develop psychotic symptoms. Symptoms of psychosis may include delusions (irrational beliefs that cannot be resolved with rational explanations) and hallucinations (seeing, hearing, feeling, tasting, or smelling things or people that are not present). People with psychosis may develop paranoia, believing that they are being manipulated by known or unknown people or forces, that there is a conspiracy against them, or that they are in danger. No amount of rational explanation changes the delusional belief. Others may be convinced that they have committed an unpardonable sin against loved ones or against their God and deserve severe punishment, even death. Some sufferers become so firmly convinced of their own worthlessness that they begin to view themselves as a burden to their families and choose to kill themselves. Occasionally, severe depression may result in hallucinations in which the depressed person hears or sees things or people that are not present; other types of hallucinations, such as smelling or feeling things that are not present, are less common in severe depression than in some other brain disorders.

The changes occurring with depression understandably result in alterations in behavior. Most individuals with moderate - to - severe depression will experience decreased activity levels and appear withdrawn and less talkative, although some severely depressed individuals show agitation and restless behavior, such as pacing the floor, wringing their hand, and gripping and massaging their foreheads. Given a choice, most begin to avoid people and activities, yet others will be most uncomfortable when alone or not distracted. In general, the severely depressed become less productive, although they may successfully mask the decline in performance if they have been highly productive in the past. In the workplace, depression may result in morale problems, absenteeism, decreased productivity, increased accidents, frequent complaints of fatigue, references to unexplained aches and pains, and alcohol and drug abuses. Severely depressed individuals have been known to work their regular schedule during the day, interact with their coworkers in a routine way, and then go home and kill themselves.

Depression is more than a mental illness. It is a total body illness. People suffering from moderate - to - severe depression experience changes in their body functions. Their energy levels fall, and they fatigue more easily. Insomnia is common and takes many forms; depressed individuals may have difficulty going to sleep or experience early morning awakenings. A subgroup of depressed patients feel an excessive need for sleep. Depressives consistently complain that their sleep is not restful and that they feel just as tired in the morning when the awake as they did when they went to bed the evening before. Some may be troubled by dreams that carry the depressive tone into sleeping hours, causing abrupt awakenings due to distress. Appetite changes are common. Physical complaints are common and may or may mot have a physical basis. Physical complaints of depressed patients cannot be overlooked, because many studies inicate an increased risk of real physical illness in people who have severe forms of depression. The reasons for this are unclear.

Types of Depression

Bereavement

Bereavement, or grief, is a normal feeling of sadness that occurs following the loss of a loved one. Uncomplicated grief is believed to advance through a series of stages that, in many aspects, mimic the illness depression, raising questions as to where normal bereavement ends and major depressive illness begins. For further breakdown of this, see book.

Adjustment Disorder with Depression

Adjustment disorder with depression is the term for the condition commonly referred to as situational depression or reactive

depression. Individuals with this malady feel sadness about a loss or major life change. The sadness, depressed mood, or sense of hopelessness begins within three months of a major stress and is excessive. People with this form of depression may find it difficult to carry on routine activities at home, at work, or at school. The depression gradually disappears once the stress is over and is not usually considered a serious depression, although it may be very uncomfortable. Often the support and advice of concerned friends, loved ones, or a doctor are enough to help sufferers manage until their mood improves following removal of stress or a decrease in it's intensity.

Dysthymic Disorder

Some depressions are chronic and can last a lifetime. Dysthymic disorder, or dysthymia, describes a more chronic condition in which individuals experience depression for most of the day, most of the time, for at least two years. Brief periods of relatively normal mood may intervene, but those periods of relief last no more than a couple of months at a time. Depression of this type may last for years, even a lifetime. Dysthymic disorder is chronic but not usually severe, yet it may cause significant problems in everyday life.

Major Depressive Disorder

Major depressive disorder (also known as unipolar depression or clinical depression) is the serious and often disabling form of depression that can occur as a single episode or as a series of depressive episodes over a lifetime. The course of major depressive disorder is variable. A single episode may last as little as two weeks or as long as months to years. Some people will have only one episode with full recovery. Others recover from the initial episode only to experience another one months to years later. There may be clusters of episodes followed by years of remission. Some individuals have increasingly frequent depressive episodes as they grow older.

During major depressive episodes. sufferers will have most, if not all, of the depressive symptoms affecting the mood, cognitive, behavioral, and physical aspects of life. The most severe forms of major depressive disorder may result in delusions and the other psychotic abnormalities described earlier in this chapter. This is one of the most disabling forms of depression.

Bipolar Disorder

Bipolar disorder is a so-called "mood swing disorder" formerly known by the more familiar term "manic-depressive illness."

Bipolar disorder is classified based on the severity of the episodic mood elevations that are interspered with major depressive episodes. In addition to episodes of severe depression, people with bipolar disorder type I experience at least one episode of mania - that is, an episode during which their mood ranges unpredictably from euphoric to irritable and is accompanied by hyperactivity, lack of need for sleep, impulsivesness, rapid thoughts and speech, poor follow-through in tasks, poor judgment in business and personal arenas, poor insight (self-awareness of changes in attitude and behavior), delusions of wealth or power or victimization by conspiracies, and often, but not always, auditory hallucinations. Visual hallucinations occur in mania, but are not as common as auditory hallucinations. Manic episodes can last for a few hours or for months, but generally extend for days to a few weeks. Manic episodes usually do not last as long as the depressive episodes also associated with this disorder. Taken as a group, bipolars tend to experience manic episodes more frequently in their young adult years than later in the course of their illness, when depressive episodes are likely to predominate. Many bipolar patients are reluctant to give up their maic episodes, even though they want relief from the depressive ones. For that reason. they often will not take mood stabilizing medications as required. Patients are at risk for suicide attempts during both manic and depressive episodes, especially when the manic symptoms become so intense as to cause agitation and psychotic symptoms.

People with bipolar disorder type II show a similar pattern of recurrent depressions punctuated by occasional mood elevations, except that the mood elevation is milder and is described as hypomania. Individuals with hypomania tend to experience episodically expansive but controllable "highs" and increased productivity while retaining reasonable insight and judgment. These "little highs" may last only a few hours before a mood swing occurs and increasingly severe depressive symptoms set in. Still, bipolar type II patients enjoy their natural highs and are loath to give them up.

Recently clinicians have become more aware of other variations of bipolar disorder often referred to as atypical bipolar disorders. Those disorders include bipolar disorder with mixed mood and rapid cycling bipolar disorder. The former is a variant in which the patient experiences episodes that appear to be a combimation of the worst features of both mania and depression. The patient mat be hyperactive, with rapid speech, racing thoughts, erratic behavior, agitation and poor judgment typical of mania but at the same time report feelings of intense depression and hopelessniss and thoughts of suicide. Clinical experience indicates that this can be a lethal combination.

Rapid cyclers are individuals with bipolar disorder who experience four or more significant mood swings per year. As this group has been more closely studied over the last decade, researchers and clinicians have identified individuals who cycle as frequently as weekly, daily, and even many times in a single day.

Atypical Mood Disorders

Mood disorders do not always cooperate by appearing as pure, clear-cut diagnostic entities. Sometimes the presentation of the illness is so complicated that diagnosis and treatment become an exercise in detective work. The most common of the atypical presentations includes a curious, episodic mood swing disorder associated with seasonal changes, a condition known as seasonal affective disorder, or SAD. This condition usually involves annual autumn/winter depressive episodes that clear in the late spring and summer.

Seasonal mood swings can be manic rather than depressive. Is this phenomenon related to SAD, or is it simply a variant of bipolar disorder? Perhaps SAD is part of a spectrum disorder with major depressive disorder on one end and bipolar disorder on the other.

In another atypical and complex mood disorder called double depression, sufferers experience a chronic low-grade depression (dysthymia) periodically intensified by episodes of major depression. This disorder can be difficult to diagnose initially, but becomes more apparent after antidepressant medication trials provide relief from the more incapacitating depressive symptoms but leave chronic, low-grade mood symptoms that do not improve with continued medication changes. At that point the clinician may suspect the presence of two simultaneously occuring depressive disorders. To further complicate the picture, clinical experience indicates that atypical depressions are often accompanied by other chronic psychiatric manifestations such as anxiety and obsessive-compulsive symptoms.

Mood Disorder associated with General Medical Condition

Depressive symptoms are common in medical and surgical patients and are formally diagnosed as depression with general medical condition where the specific medical condition is named. The reasons are varied and complex, but common issues include loss of health, helplessness, lowered self-esteem, fear for the future, feelings of vulnerability, chronic disability and pain, financial stresses, and alterations in personal relationships. While depression may be secondary to the stresses of medical or surgical illness, it may also be a result of medication used to reat those conditions. For further breakdown and analysis and discussion see book.

Depression Associated with Seasonal Variations

Seasonal affective disorder - is a cyclical mood disorder varied with the seasons of the year. SAD, is the short version.

The current thought is that SAD results from seasonal variations in a person's exposure to sunlight and that, therefore, the frequency of SAD should be highest in populations living closest to the earth's poles and least noticeable in populations living near the equator. For further discussion, see book.

The Causes of Depression

Ancient writings describe the affliction laid its cause to supernatural intervention, primariy religious in nature. In the Hindu texts, gods personifying good and evil warred with one another and victimized individual humans. In texts from Babylonia and Egypt, gods punished transgressions in the hearts of people and placed on them the depressive curse. The early Hebrew texts allude to the belief that depression in humans reflects the displeasure of Yahweh. The ancient Greeks also described a melancholic temperament that compares to our current concepts of dysthymic disorder, a milder but often lifelong form of depression.

During the Middle Ages, as in all ages, many people turned to supernatural explanations for mental illness. Depression became God's punishment for sinners or the natural condition of souls under the control of the devil. This was the age of witch hunts, when many unfortunate women and some men were accused of being in league with Satan and severely punished for the sin of mental illness, including depression.

Psychosocial Theories

Psychoanalytic Theories

Sigmund Freud looked to the mind for the cause of depression and other mental illnesses, eventually developing the school of theory and treatment of mental illness that came to be known as psychoanalysis. He postulated that illnesses of the mind are caused by unconscious conflicts between human instincts (which he called collectively the "id") and the human conscience (which he called the "superego"). His initial theory emphasized the basic role of unsatisfied, primitive sexual drives in developing intolerable levels of anxiety. If acted upon indiscriminately, powerful sexual drives can place individuals in conflict with their environment, causing further distress. Freud proposed that, to avoid such potentially damaging conflicts, individuals often mask their primitive sevual drives by developing characteristic methods to subdue the intolerable levels of anxiety. Freud called these methods "defense mechanisms" and concluded that individuals varied as to which ones they tended to rely on most, accounting for the differing temperaments among humans. He noted that ongoing attempts to balance the demands of the masked sexual drive and the demand of the environment are associated with unrecognized or unconscious conflicts, which themselves tend to produce anxiety. Freud believed that depression results from failure of characteristic defense mechanisms to effectively deal with unconsciously generated anxieties. Theorists also point out that loss of self-esteem is an almost universal phenomenon in significant depressions. They believe the loss of self-esteem arises from an internal conflict between our expectations ("ego ideal") and the realities of our lives.

In simpler terms, the psychoanalytic theory explains depression as a result of the individual's inability to effectively deal with significant loss and with largely unexpressed and frequently unrecognized anger. Modern therapists who subscribe to this theory believe that the loss and unexpressed rage may be related to significant events other than loss of relationships, such as, for example, being passed over for a desired promotion, being the victim of an assault, being involved in a serious accident. losing financial security, or failing academically.

Behavioral Theories

Behaviorists theorize that humans come into the world as a blank slate, or tabula rasa, on which their experiences write the scripts for their lives. Behavioral theorists focus on the individual's tendency to overrespond to loss of social supports. When the social environment no longer supports individuals and no longer reinforces their behavior, feelings of isolation, discomfort, and fear result. Behaviorists believe that the lack of social support is one of the strongest factors in the production of depression. They point to a vicious cycle that can intensify and prolong the depression. Depressed people tend to elicit negative responses from people.

Environmental Theories

Modern studies seem to indicate that the likelihood of depression increases five to six times in the six months following a stressful life event.

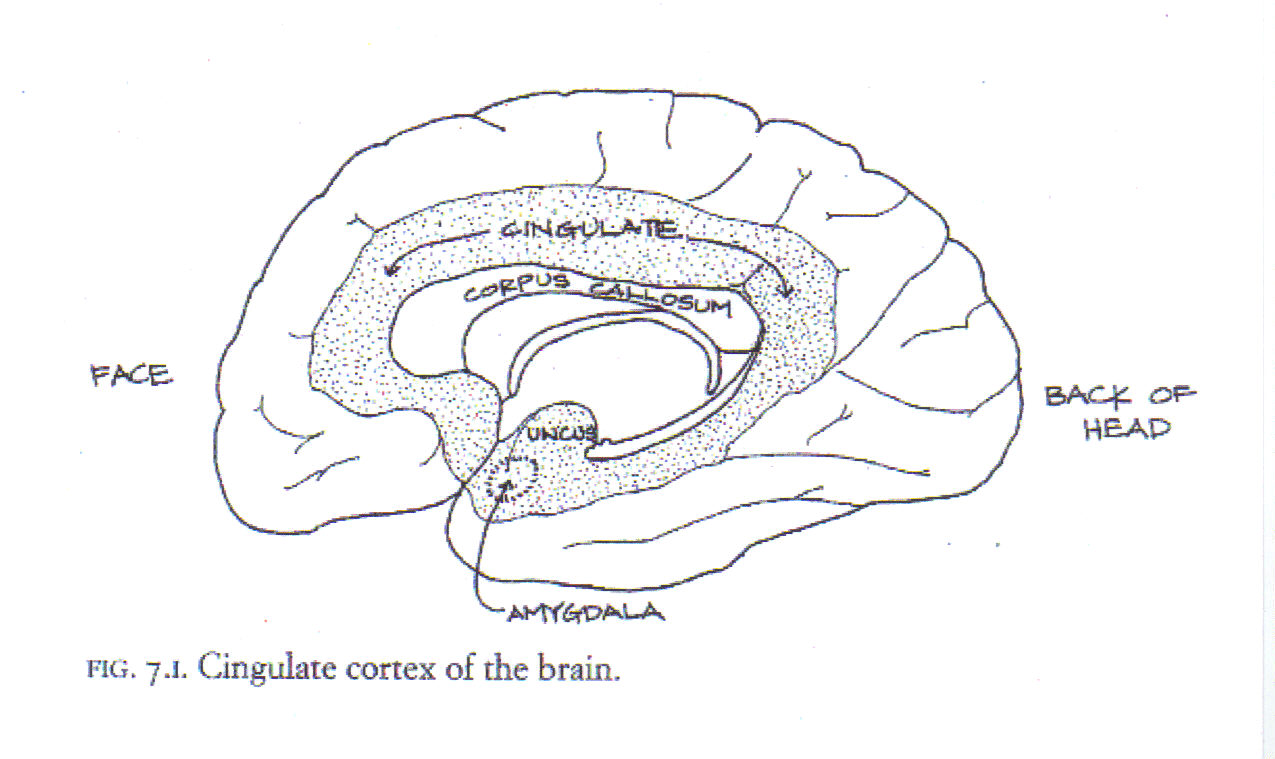

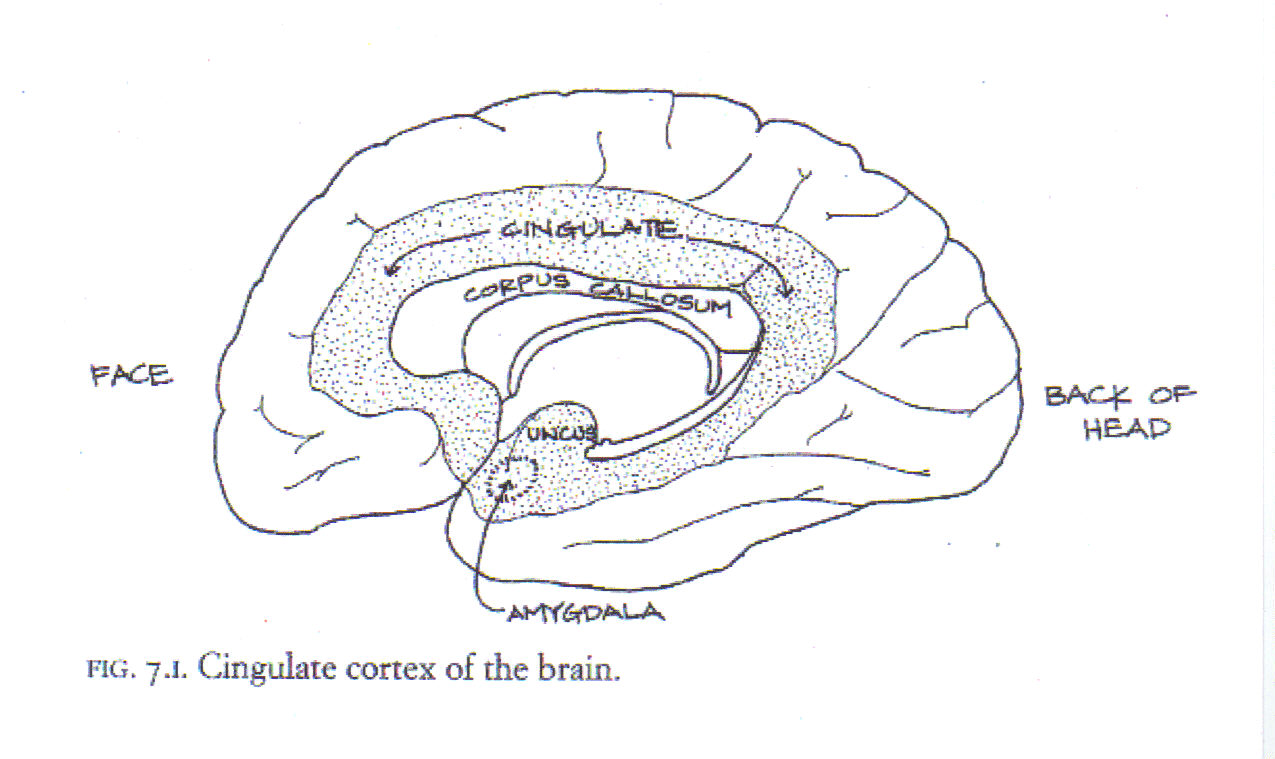

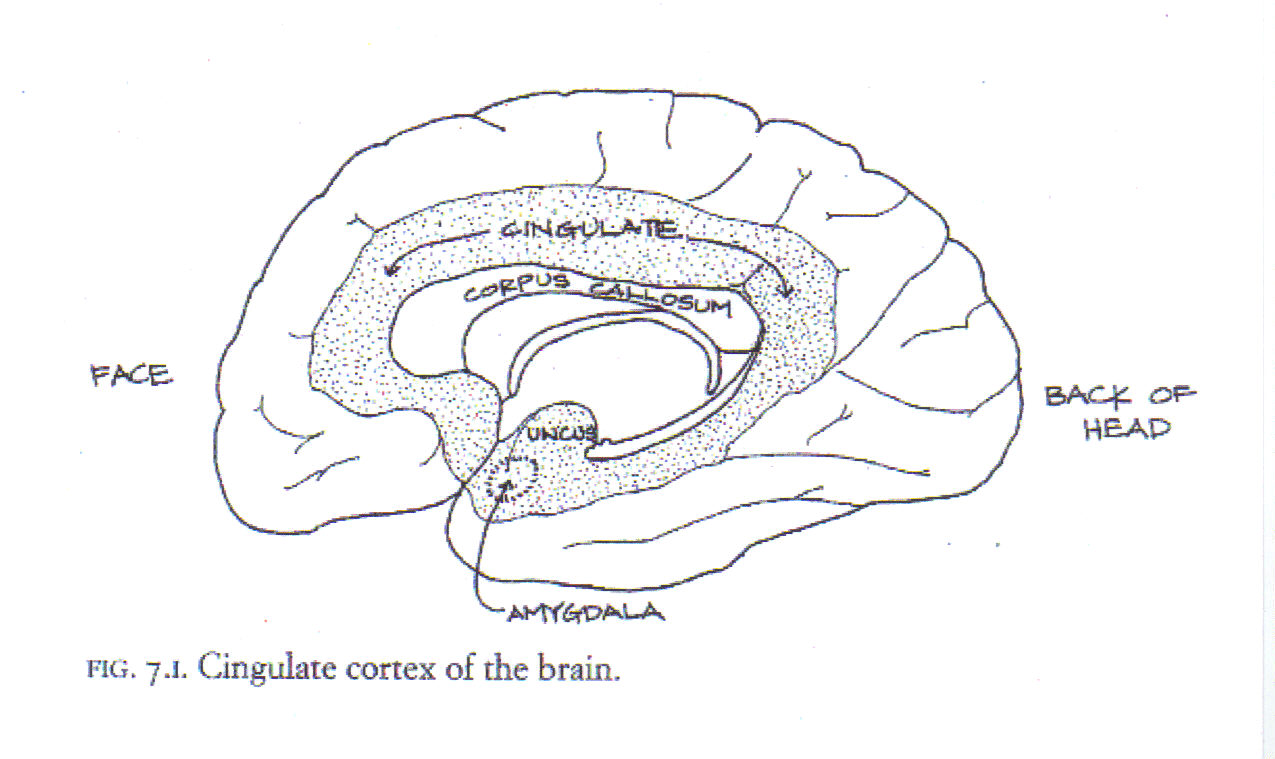

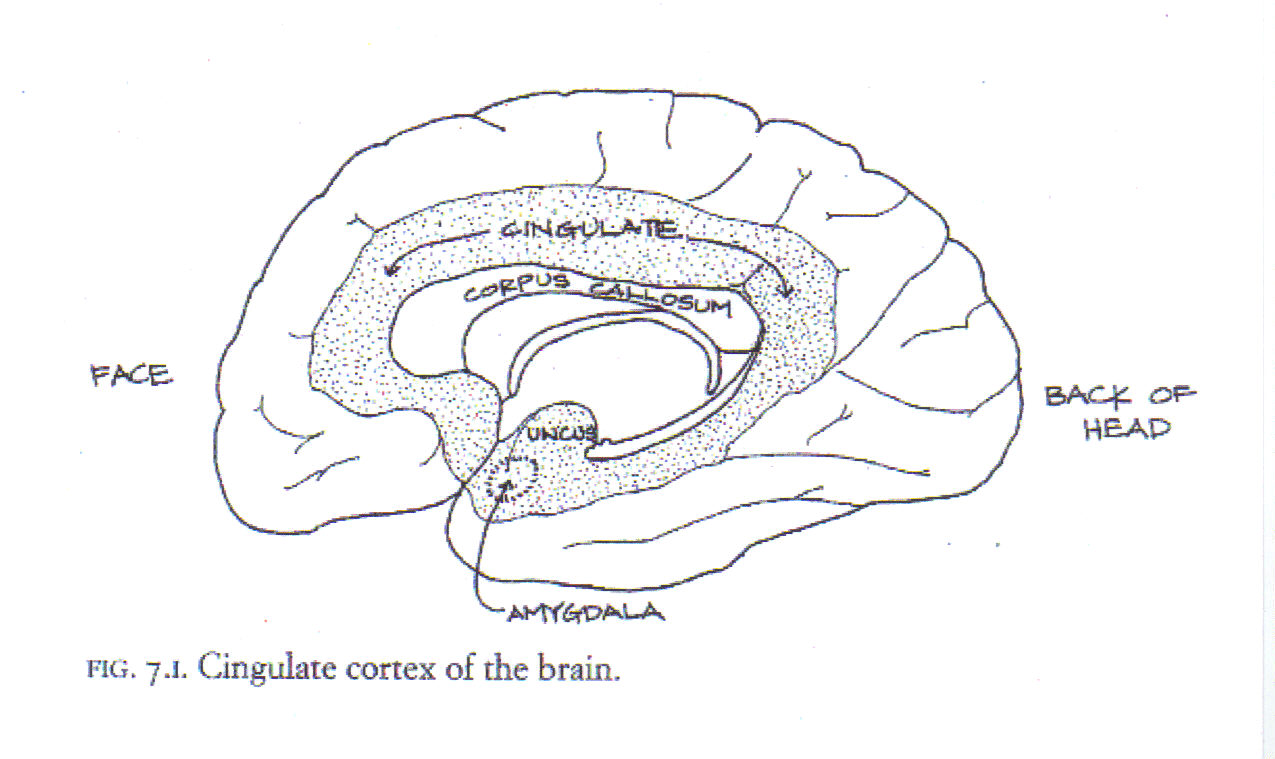

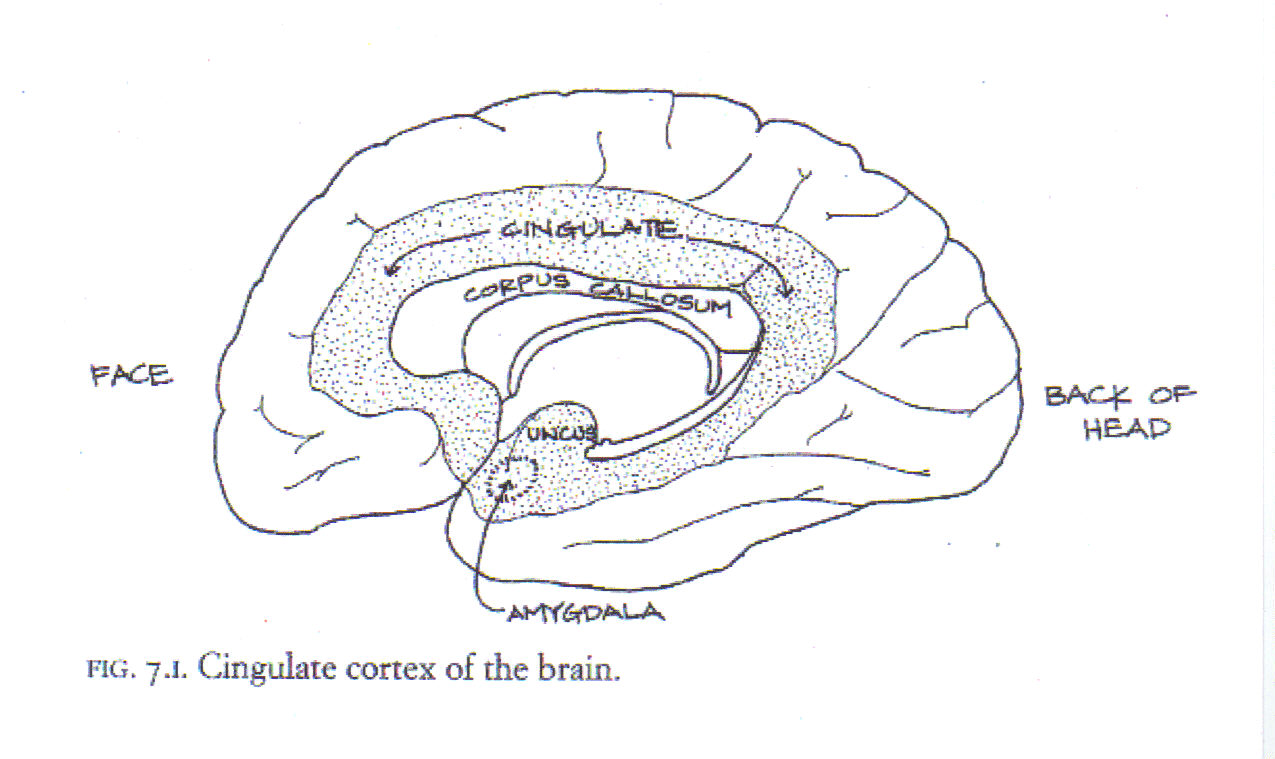

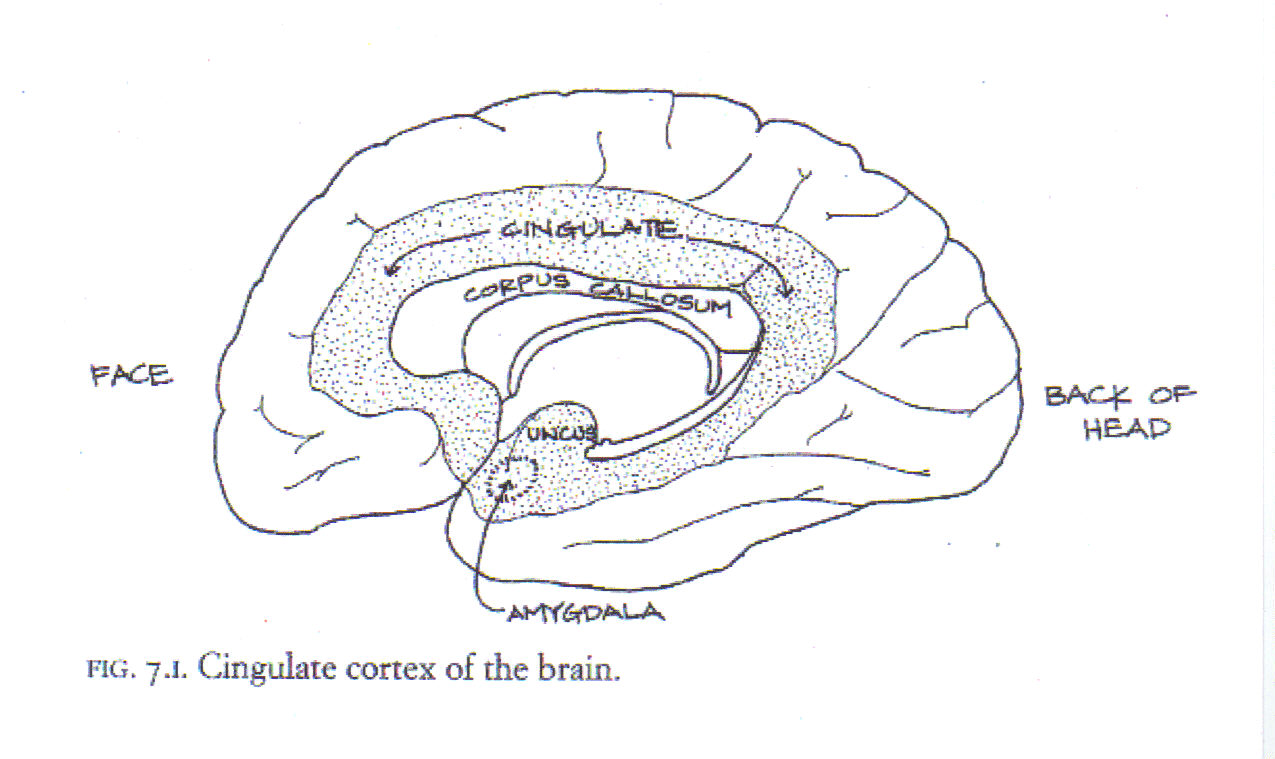

Some studies suggest that early stressful life events (such as parental loss, emotional or physical deprivation, or physical, sexual, or emotional abuse) may sensitize humans so that they are more likely to develop depression in later life in response to significant stresses. One model that attemppts to explain this phenomenon is the "kindling-sensitization" hypothesis, which proposes that, just as repeated exposure to poison ivy may eventually result in an allergy to the noxious plant, repeated stresses tend to sensitize the areas of the brain specializing in emotional responses (the limbic system so that the cumulative effects of stresses over time produce the mood and behavioral alterations we know as depression.

Biological Abnormalities in Depression

Knowledge of the brain and its functions expanded in the latter quarter of the twentieth century. Researchers discovered changes in the mind / body connections and function of people with serious depression.

Advances in technology, including assay methods capable of identifying specific receptor sites and imaging techniques such as positron emission tomography (PET), single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), and, most recently, functional magnetic resonance imaging (ƒMRI, which is potentially more available and cost effective), have allowed researchers to identify activity levels in various brain regions associated with different mental and physical activities. The brain imaging techniques most commonly used by clinicians today remain computerized tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) because of availability and cost.

Computerized tomography (CT) scans visualize the brain by measuring differences in the density of different tissue components (cerebrospinal fluid, blood, bone, gray matter, and white matter). Data is obtained by passing X-ray photons through the brain onto a detector. The data is then transmitted to a computer that generates a three-dimensional view of the brain at various levels. A CT scan is used when brain abnormalities such as mass lesions (tumors, abscesses, and hemorrhages), calcifications, atrophy, areas of infarction, or boney abnormalities in the skull are suspected. Details of brain tissue and abnormalities in the area of the brain stem and the cerebellum are not well visualized by CT scanning techniques.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) relies on the use of a magnet and radio waves similar to AM/FM radio waves. It produces detailed images of brain anatomy at different levels so that the scan resembles a fine hand-drawn pen-and-ink illustration. The data is processed by a computer to produce three-dimensional images of the brain at various levels. MRI produces images that are superior to CT scans in differentiating white matter from gray matter and in defining individual brain structures. Because CT scans are more readily available in most medical facilities, and because they are cheaper than MRI scans, CTs remain the brain imaging technique of choice unless the clinician suspects a small lesion in an area that is difficult to visualize and in cases in which a demyelinating (destruction of the protective sheath surrounding nerves) condition such as multiple sclerosis is suspected.

A recent elaboration of MRI scanning is the funtional MRI (ƒMRI). That scan allows visualization of the anatomy of the brain as well as its activity in response to predetermined stimuli, such as instructions to move a finger or imagine a sad scene. The ƒMRI uses one of four techniques, but most commonly relies on differences in the magnetic properties of oxygenated red blood cells (as compared to nonoxygenated red blood cells) in order to measure regional differences on oxygen use by brain tissue. Brain tissue engaged in tasks require more oxygen than brain tissue "on standby". The ƒMRI thus indicates which parts of the brain are using increased amounts of oxygen and, by inference, are more active. Unlike positron emission tomography and single photon emission computed tomography, the ƒMRI is not invasive and does not involve the infection of radioactive materials.

Positron-emission tomography (PET) and single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) both provide multicolored images roughly correlating colors with the level of activity in specific areas of the brain, but do not yield precise anatomic images of the brain. Both scanning techniques, which are invasive, require injection of a mildly radioactive organic compound (such as glucose or oxygen) into the bloodstream and track the compound from the blood. Active brain cells use more glucose than inactive ones, so active regions of the brain consume larger amounts of radioative glucose and show up on the PET and SPECT scans as intensely colored areas.

Brain Imaging

Brain imaging research relies on several advanced scanning techniques - MRI, ƒMRI, PET, and SPECT. MRIs provide excellent anatomic images of brain structures at various levels, but do not provide evidence of brain activity. PET and SPECT scans provide images that allow comparison of activity in different areas of the brain but require the injection of a short-lived, mildly radioactive organic material, thus limiting their value in repeated studies on human volunteers. An ƒMRI produces images of activity levels in various areas of the brain without requiring use of radioactive materials, allowing human volunteers to be studied repeatedly.

Researchers compare ƒMRI, PET, and SPECT scans of depressed patients with those of nondepressed individuals. They also compare scans of individuals before and during specific kinds of brain activity. For instance, which areas of the brain "light up" (i.e., are more active) when individuals with their eyes closed are asked to imagine sad thoughts? Do scans reveal consistent abnormalities in brain structure or activity levels in depressed people? Does the image pattern change following successful treatment for depression?

Everything You Need To Know About / Depression

Eleanor H. Ayer

Depression describes a person's condition when he or she feels sad, discouraged, and hopeless. Often, a depressed person has trouble functioning. He or she might feel exhausted all the time and have difficulty thinking clearly. For some people, depression is caused by an imbalance of chemicals, or hormones, in the body. A person's mood sometimes depends on the chemical makeup of those hormones. If they are out of balance, the person can become depressed.

Depression affects people differently. It can make some people feel tired all the time, yet they may have trouble sleeping at night. Others might lose their appetites or may suddenly start overeating. A depressed person can feel hopeless, helpless, and, worst of all, alone. It becomes easy for depressed people to feel trapped by their troubles.

Seasonal affective disorder - is often referred to as "winter blues". A reaction to lack of sunlight in winter, mild or major depression develops in late autumn and clears up in early spring. This condition becomes more common as distance from the equator increases.

Postpartum depression - results from the enormous hormonal changes that occur when pregnant women give birth and begin in the challenges of caring for an infant. Some two-thirds of new mothers experience this form of depression. However, about 10 to 15 percent become clinically depressed. And about 1 in 1,000 becomes so severly depressed that the person needs to be hospitalized.

Depression often manifests itself physically in the form of physical ailments such as headaches, back pain, irritable bowel syndrome, chronic fatigue, anxiety, sleep problems, and shortness of breath.

Depression does have clear biochemical roots that affect nerve cells in the brain. Severely depressed people have unusually low levels of several brain chemicals: the neurotransmitters serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine.

What to look for

º Thoughts or suggestions of death or suicide

º Feelings of guilt or worthlessness

º Lack of physical and mental energy

º Lack of interest or pleasure in most activities

º Too much or too little sleep

º Rapid mood swings

º Argumentativeness

º Problems concentrating, making decisions, or solving problems

º Trouble making or keeping friends

º Absence of goals in life

º Trouble finishing projects or doing even simple tasks

º Change in appetite: rapid weight loss or weight gain

º Upset stomach, headache, or numbness in parts of the body

º Hyperactivity

º Slowness of speech

º Failure to pick up after oneself

º Hallucinations (strange, unreal perceptions)

º Pessimism (always expecting the worst)

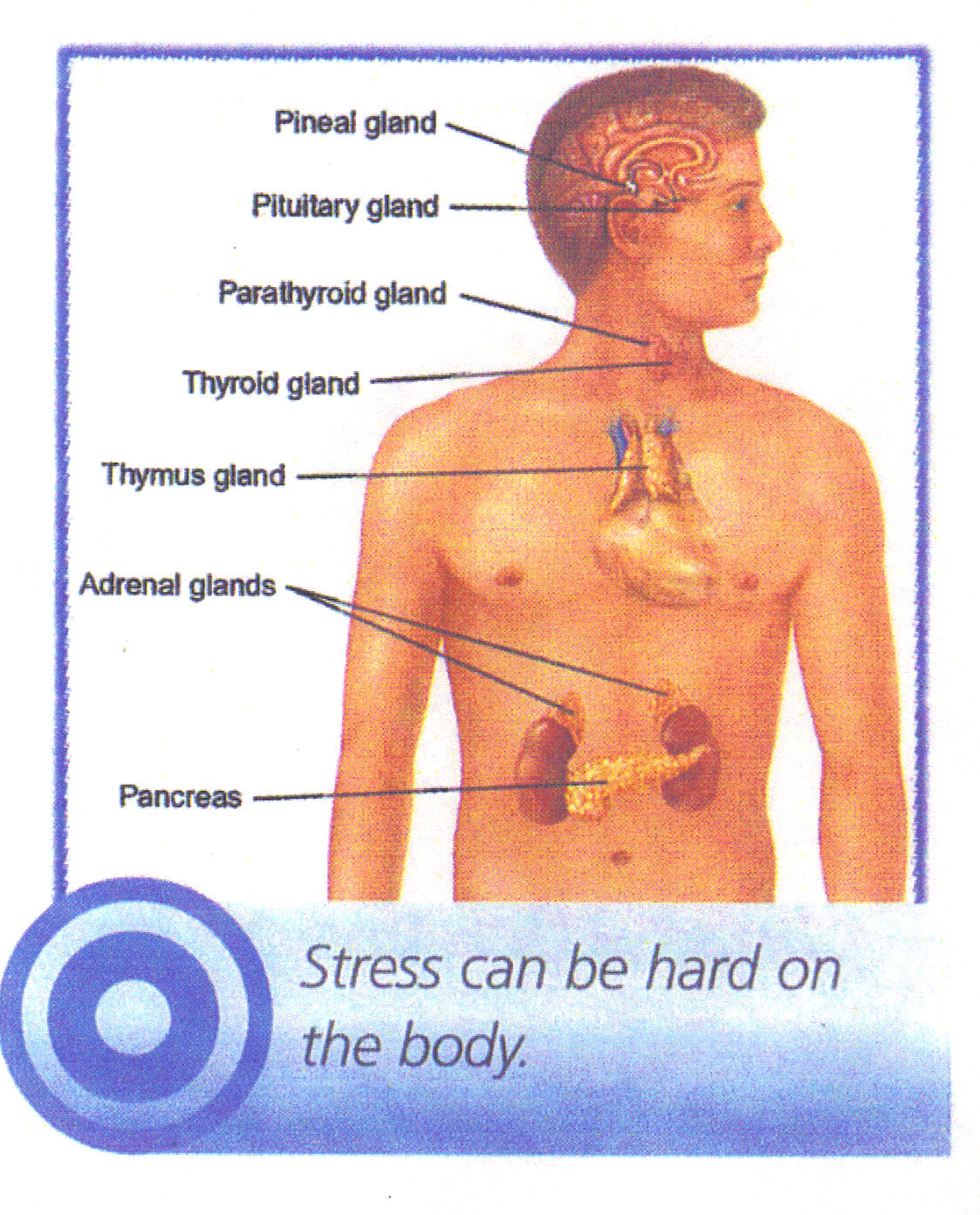

What Causes the Body to Develop Depression?

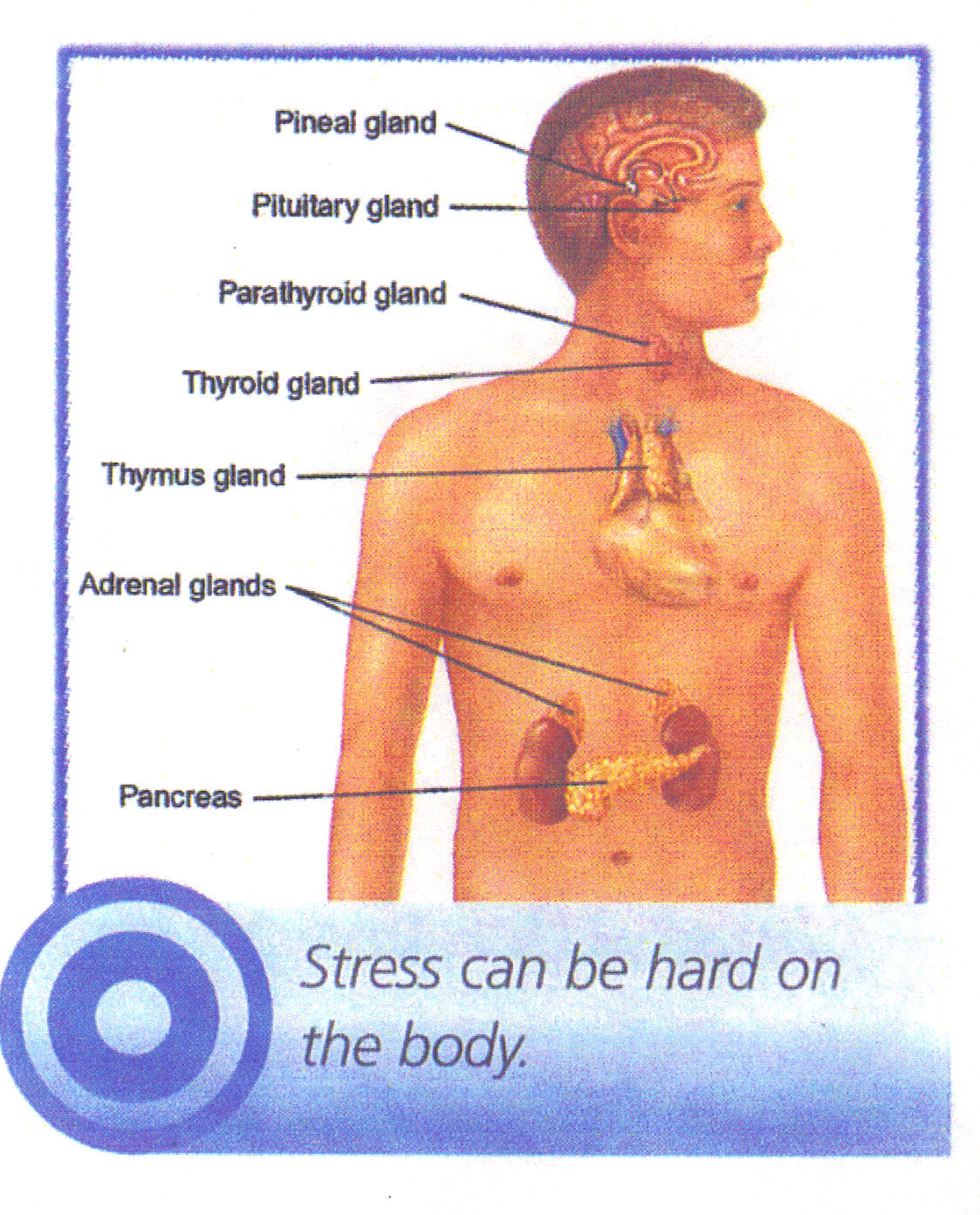

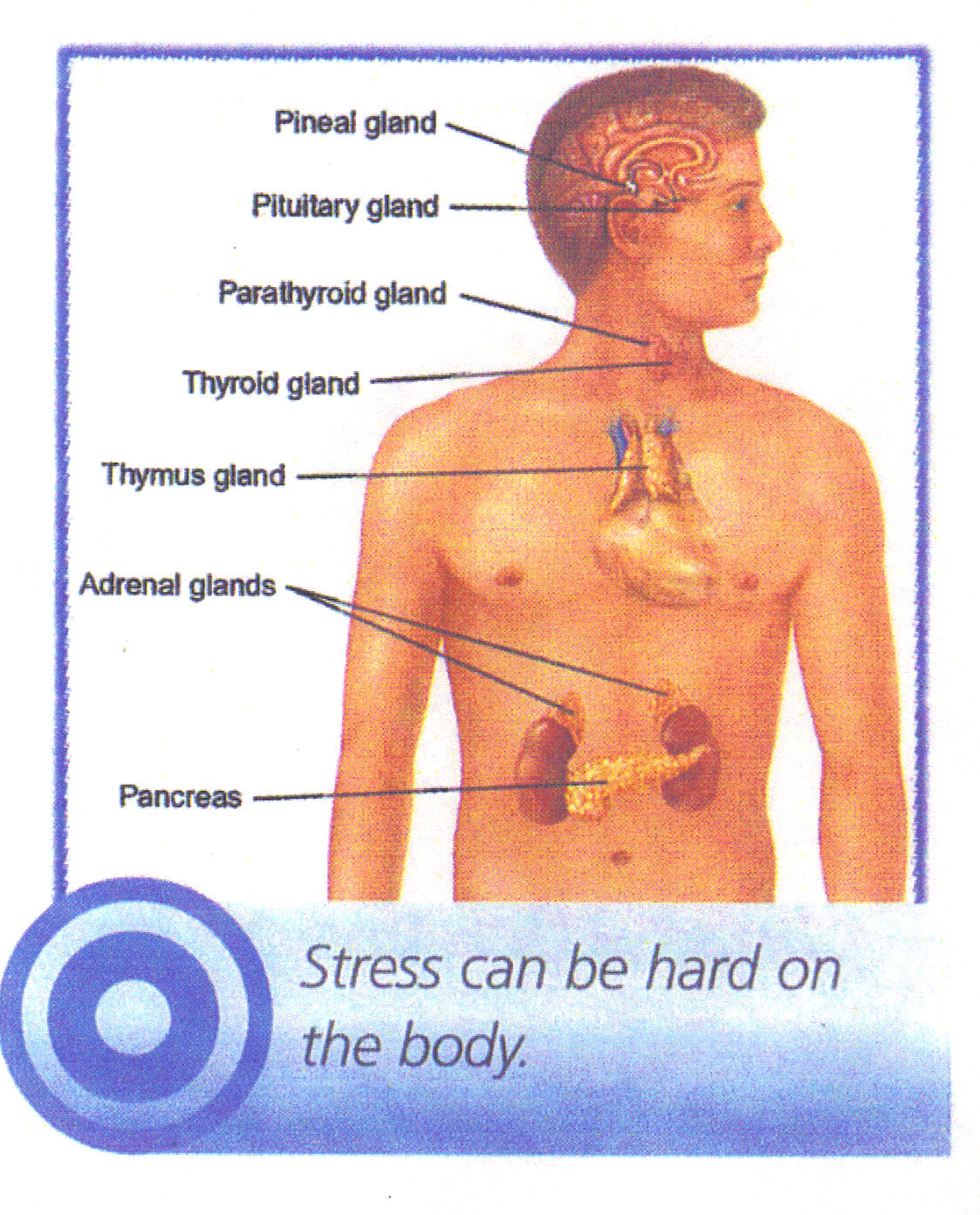

When stress becomes too great, our body goes into the "fight or flight" response. Our brain gives us two choices: We can run from the thing that is causing the stress (flight), or we can stand firm and face it (fight). To prepare us for the choice we make, our body produces hormones. These chemicals help us react under pressure. One common stress-fighting hormone is adrenaline.

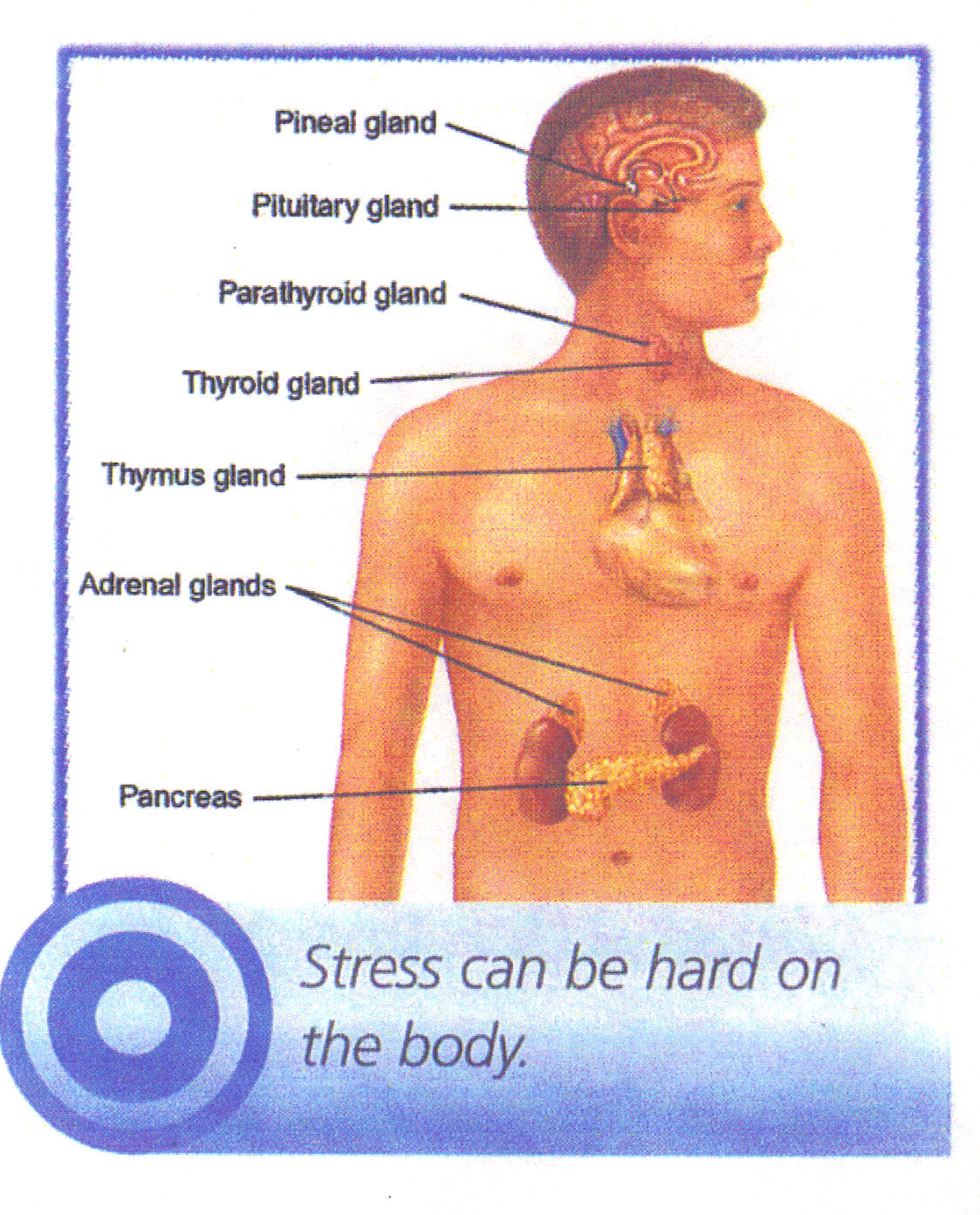

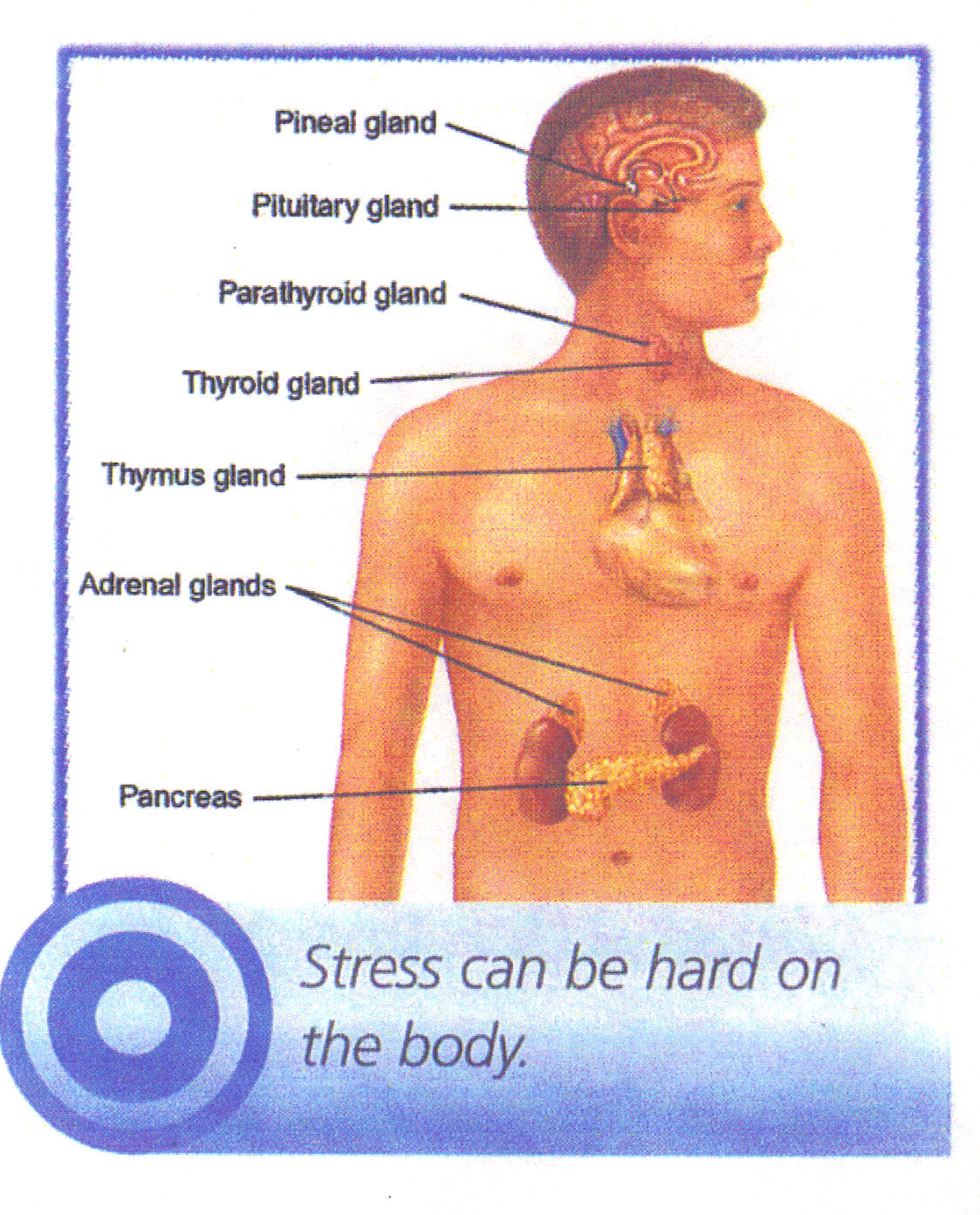

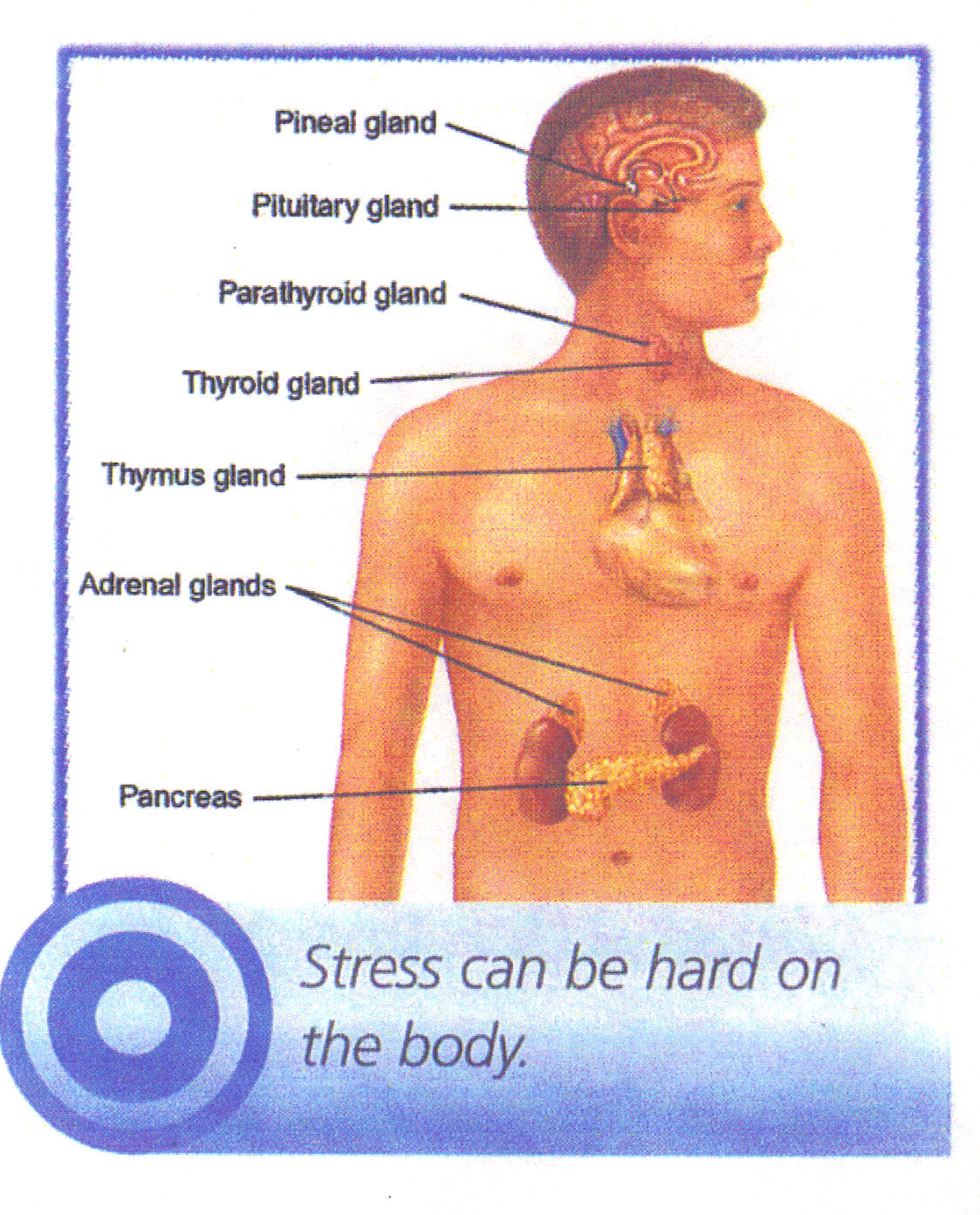

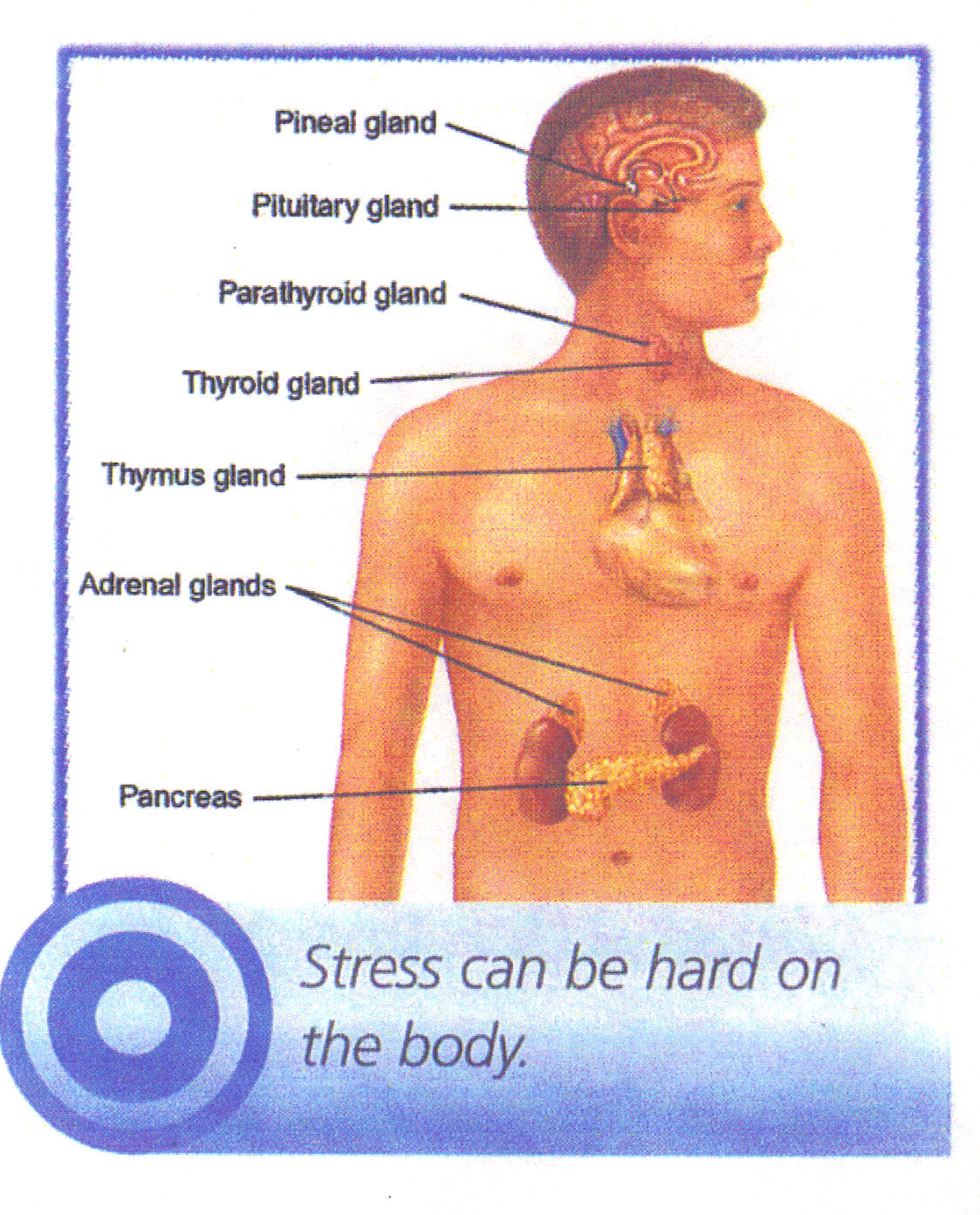

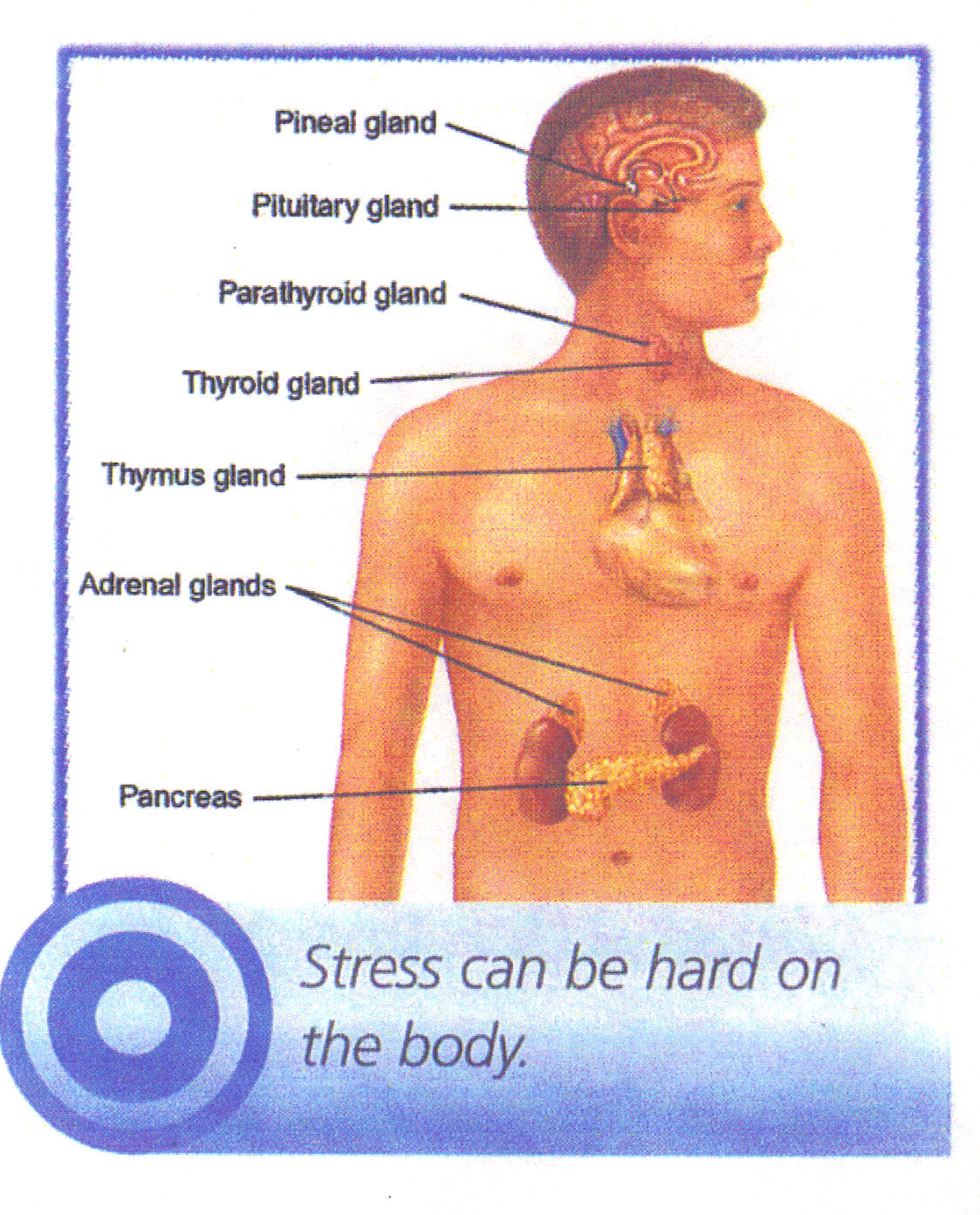

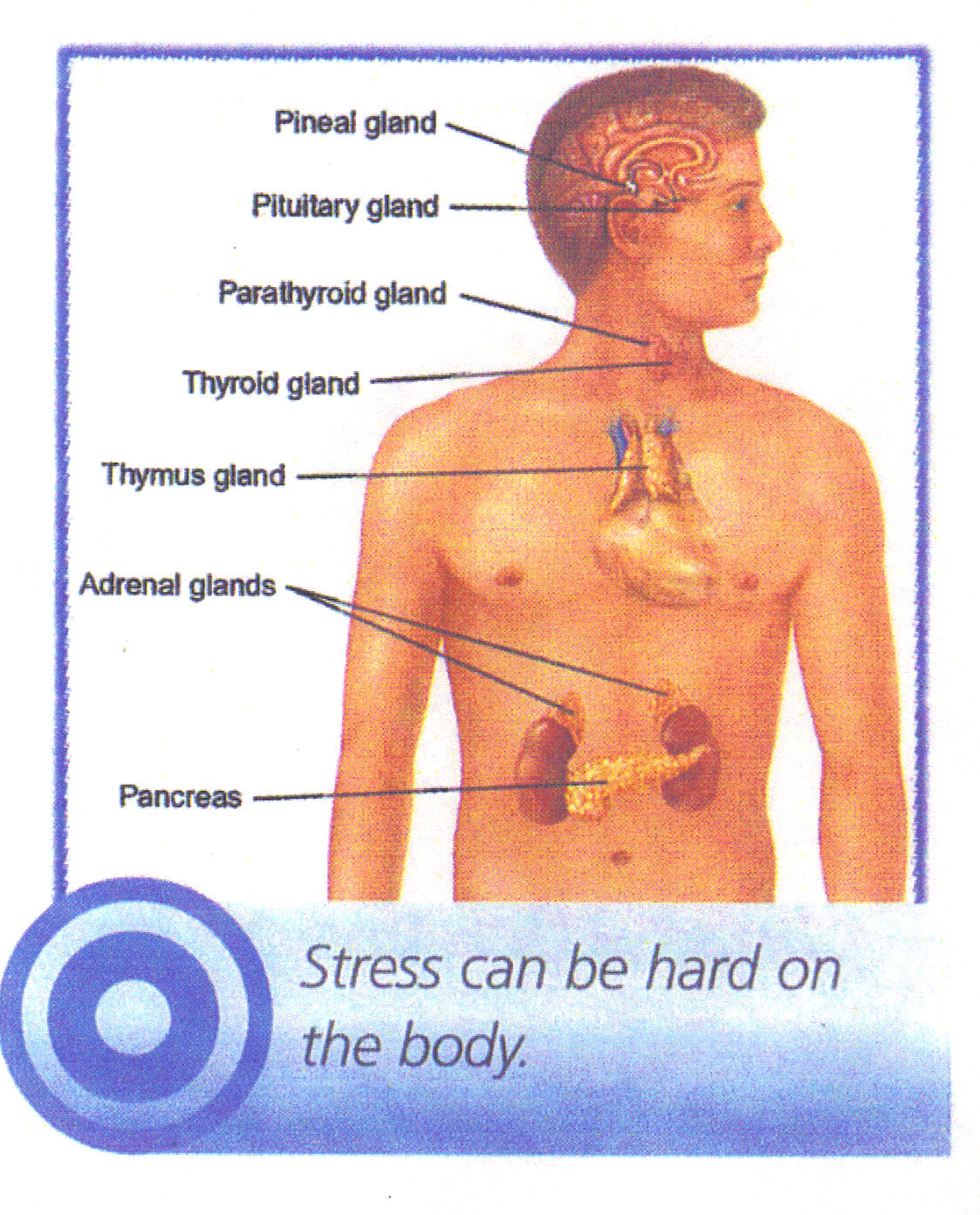

Stress is very hard on the body. It is particularly hard on the endocrine system, which is in charge of producing hormones. Under constant stress, the endocrine glands get out of balance. They produce too much or too little of the different chemicals our bodies need.

The master gland of the endocrine system is the thyroid. This complex gland affects many body functions, especially growth. It works closely with the adrenal gland, which produces adrenaline for fight or flight. A person whose thyroid is too active may show signs of mania. He or she may be hyperactive and have trouble sleeping. When the thyroid is underactive, the body can go into depression. The person becomes exhausted. He or she has little energy.

When our hormone balance is upset, it has a great effect on our emotions. A chemical imbalance in our body can change our mood, our mind, and our feelings.

Depression What We Know

Brana Lobel

Robert M.A. Hirschfeld, M.D., chief, Center for Studies of Affective Disorders, Clinical Research Branch, Division of Extramural Research Programs, NIMH.

Printed 1984, Reprinted 1985

The word "depression" has many different meanings. In psychiatry, depression max range from a transient, momentary feeling of emotional dejection all the way to a severe disorder that can stop a person from functioning, cause a slowdown of body processes, and even, in some cases, lead to death.

Depression can also be a symptom of a physical or psychiatric illness or other clinical condition. As a symptom, it can be associated with a number of psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia, anxiety, neurosis, alcoholism, hysteria, and personality disorders. It is also associated with a variety of physical illnesses including disorders of the endocrine system and the central nervous system, viral dideases, and responses to certain drugs.

Major Depression

This condition is characterized by a depressed mood, which can run from a feeling of dullness or apathy all the way to total hopelessness and deep despair. It is often accompanied by frequent crying. Anxiety is sometimes present: the person may be tense, nervous and jittery or sad and miserable. Irritability, touchiness and anger can occur. Changes in thinking also characterize this condition: slowing down of thought, inability to concentrate, difficulty with memory, indecision. Often the person believes himself or herself to be helpless, worthless, guilty. Self-blame, lowered self-esteem, and feelings of failure are common; thoughts of suicide and sometimes active plans are not uncommon.

There is usually a series of changes in somatic or body functioning. Sleep disturbances are common: there maybe difficulty getting to sleep, troubled sleep with frequent wakings, or early awakening (2 or 3 hours before the usual time) with inability to go back to sleep again. For some, the problem is oversleeping. Eating problems may occur: the most characteristic pattern is loss of appetite and weight, but increased appetite and weight sometimes also occur. Energy loss, feelings of lethargy or inertia, and slowed speech and movement may also occur, although sometimes the reverse may be true and there is agitation and hyperactivity (restlessness and pacing, for instance). Other physical changes, such as alterations in bowel habits (constipation is common), dry mouth, headaches, and a variety of aches and pains aren sometimes seen.

Perhaps most characteristic in depression are the general changes in behavior: there is loss of interest in things, people events and activities previously considered pleasurable, a diminished capacity for affection, a loss of interest in sex, and an overall loss of satisfaction with life.

In major depression, these symptoms are marked; they range from moderate to severe and seriously interfere with, or actually prevent a person from leading his or her usual life. In some cases, the condition is accompanied by psychotic symptoms, such as delusions and hallucinations.

Unipolar and Single-Episode Depressive Disorder

Approximately 50 percent of people who experience a major depression have only one serious episode in their lifetimes. For the others, the condition reappears and is called unipolar disorder (meaning recurrent major depressive episodes). The course of unipolar disorder may vary: episodes may be separated by long intervals, sometimes many years, or normal functioning, they may be closer together, or may cluster. For some, episodes increase in frequency with advancing age. Symptoms of a major depressive episode usually appear over a period of days to weeks, although sometimes they are more sudden. Untreated, an episode generally lasts an average of 1 year.

Manic Episode

In this condition, the mood is elevated and euphoric (the so-called "high"). Irritability may also be present. People in a manic state are hyperactive, and often get by on very little sleep. They have inflated or grandiose ideas about themselves. Their speech can be pressured and rapid, their thoughts move very quickly from one topic to another, and they are easily distractable. They often show very poor judgment and may go on wild spending sprees, invest unwisely in business, or have indiscreet sexual relationships. Energy and socialability are increased. There are sometimes psychotic symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions. The latter are often of a grandiose variety - for example when the depressed person claims a special relationship with a celebrity or well-known political figure. The symptoms can range from moderate to severe; with moderate symptoms, a stranger may not recognize the condition as a disorder, but those who are close to the individual may see the behavior as excessive and unusual. Manic episodes usually begin suddenly, and symptoms increase over a few days. They can last for a few days to a few months; typically they are much briefer than depressive episodes.

Bipolar Disorder

Bipolar disorder (sometimes called manic-depressive illness) is characterized by episodes of mania alternating with episodes of depression. In bipolar disorder the first episode is often manic; although a very small number of people have only manic episodes, most people will have both manic and depressed episodes. Frequently an episode of one type is followed immediately by a brief episode of the other type. In general, the episodes are more frequent and shorter than those in unipolar disorder. The course over a lifetime, as with unipolar disorder, is variable.

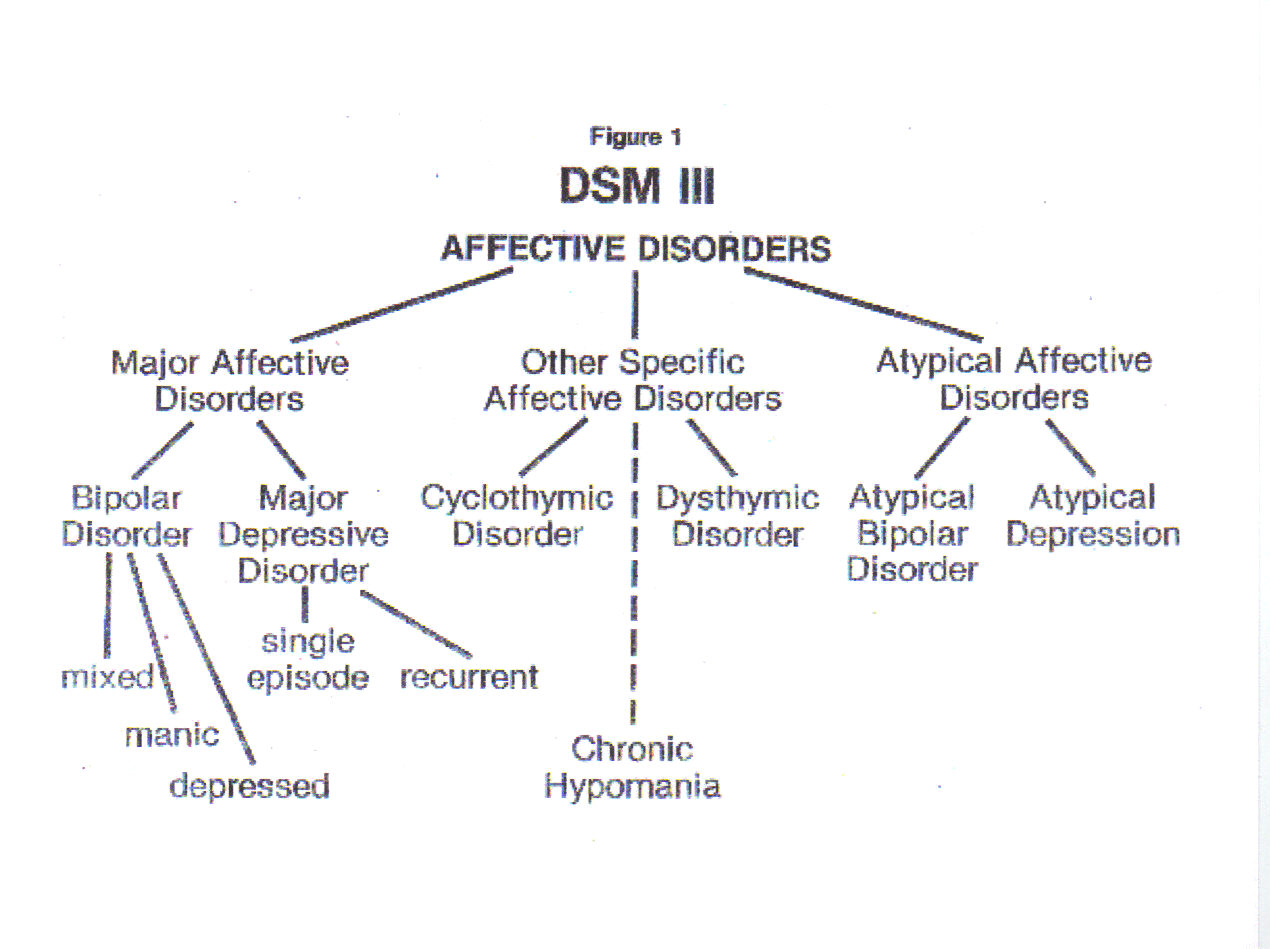

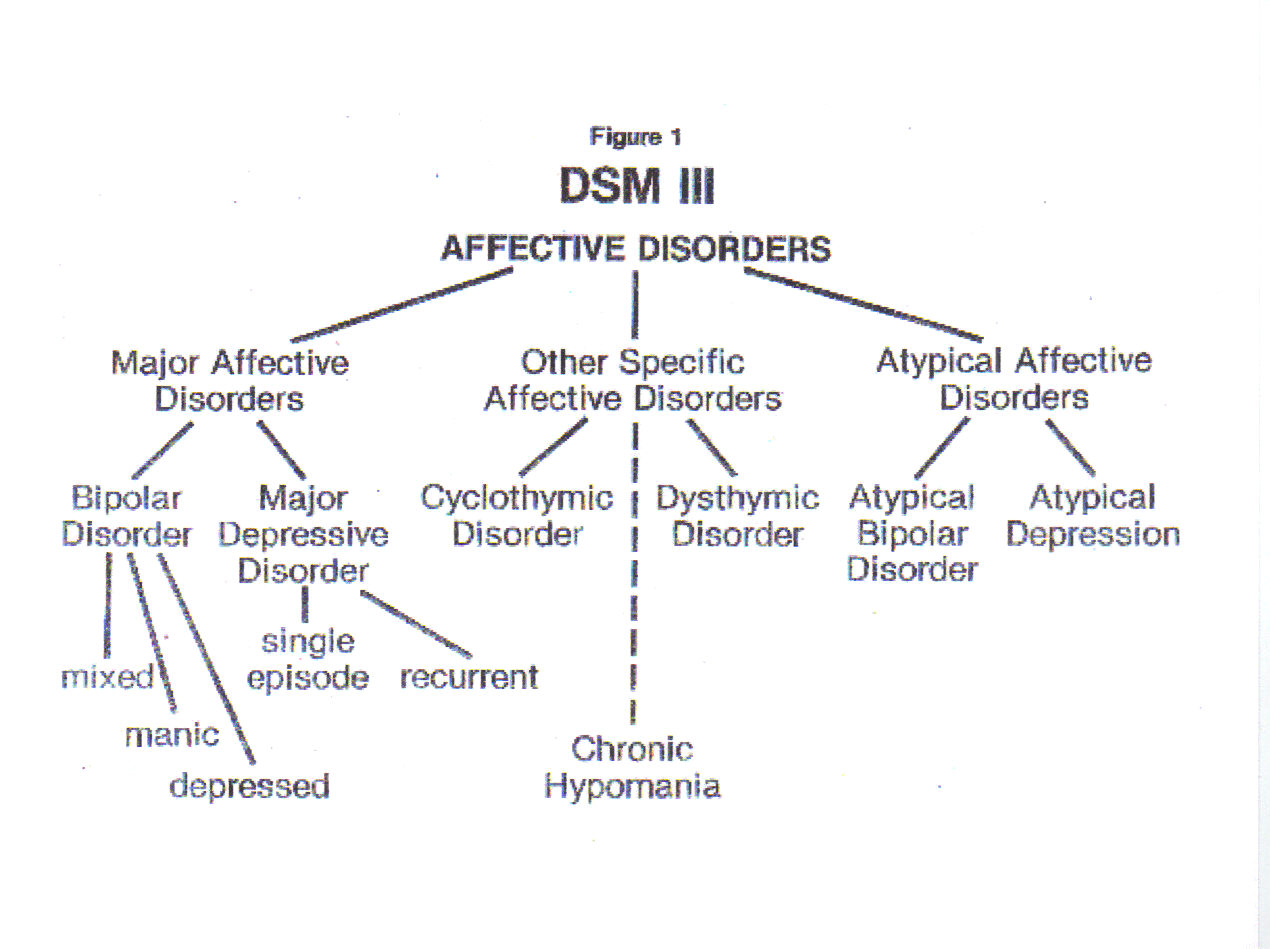

Dysthymic Disorder

This condition is also called "depressive neurosis." It is characterized by depressed mood (dysphoria) or loss of interest in usual pleasures and activities, accompanied by the associated symptoms of unipolar disorder but without the severity or duration found in the latter. The condition may persist, or it may be intermittent, with "normal" moods that last from a few days to a few weeks. For adults, the condition must have been present for 2 years to be diagnosed as a clinical depressive syndrome. Psychotic symptoms are not present. Dysthymic disorder can be described as mild to moderate; onset is unclear and the course is chronic.

Cyclothymic Disorder

This condition is characterized by a chronic mood disturbance of at least 2 years' duration, involving numerous periods of depression and hypomania (mild manic symptoms). Associated symptoms will be neither as severe nor as long-lasting as in a serious manic or depressive episode. In cyclothymic disorder, the depressive and hypomanic periods may be separated by periods of normal mood lasting for months at a time; or the two types of periods may be almost simultaneous or may alternate with each other.

Depressed and hypomanic periods are characterized by "paired symptoms." For instance, feelings of inadequacy during depressed periods and inflated self-esteem during manic periods; social withdrawal and uninhibited quest for companionship; sleeping too much and decreased need for sleep. There are no psychotic symptoms; onset is usually unclear and the disorder has a chronic course.

Classifying Depression

Psychotic / Neurotic

In early research on depression, a distinction was made between clinically depressed people who were psychotic and those who were depressed without being psychotic. Some researchers considered psychotic depression a specific condition of organic origin, as contrasted to "neurotic" depression which was milder and thought to be largely of environmental origin. Other theorists considered that psychotic and neurotic depression were not two separate conditions, but two different ends of a single continuum. Currently, neither of these theories has been proven. One difficulty with this distinction is the multiple meanings given to both psychotic and neurotic depression. The term "psychotic depression" may refer to severity, to psychotic symptoms such as delusions and hallucinations, to severe social incapacitiation, and/or to somatic symptoms. The term "neurotic depression" may be used to mean the absence of any or all the major characteristics of psychosis, or to depression stemming from "neurotic conflicts" as proposed by psychoanalytic theory.

Endogenous / Nonendogenous

The concept of endogeneity in clinical depression has been used over time in a number of different ways. "Endogenous" means "coming from within." Currently, the term "endogenous depression" refers to a set of symptoms involving early morning awakening, loss of appetite and weight, disturbances of the psychomotor system such as agitation and lethargy, daily variations in mood (often, more noticeable depression in the morning), severe depressed mood, and lack of reaction to environmental stimulation. Many of these symptoms involve disturbance of basic bodily functions; the endogenous condition is suspected of having more direct relationship to biological factors than some other types of depression. Recent research has shown that people characterized as endogenously ill than other depressed people, have basically normal personalities before the depressive episode, and show the greatest response to antidepressant drug treatment.

Primary / Secondary

Clinical depressions can be classified as primary: that is, the depressed person has had no previous psychiatric disorder (or has only had episodes of depression or mania), or secondary: the depressed person has a pre-existing psychiatric disorder (for example, schizophrenia or alcoholism) on which a clinical depression is superimposed. This is primarily a research distinction intended to select a group of "pure" depressive subjects for a better study of causes.

The primary/secondary distinction is also used in connection with physical illness. People who develop depressions clearly caused by or associated with certain diseases, drug responses, or other physical conditions are considered to have secondary depressions.

Unipolar / Bipolar

Unipolar disorder is defined as one depressive episode or a history of only depressive episodes, or far more rarely, one manic episode or a history of only manic episodes. Bipolar disorder, in contrast is the occurence of both manic and depressive episodes, either separately or concurrently. There is increasing evidence that unipolar disorders and bipolar disorders represent different types of depression, with some overlap. Much information from genetic, biochemical, and pharmacological studies support this distinction.

Depression & The Body

Copyright© Alexander Lowen, M.D., 1972

Preface

If the break with reality is severe - that is, if the patient isn't oriented in the reality of time, place, or identity - his condition is described as psychotic. He is said to suffer from delusions that distort his perception of reality. When the emotional disturbance is less severe, it is called a neurosis. The neurotic individual is not disoriented, his perception or reality is not distorted, but his conception of reality is unsound. He operates with illusions, and consequently his functioning is not grounded in reality. Because he suffers from illusions, the neurotic person is also considered mentally ill. The depressed person is physically depressed, as well as mentally depressed; the two are really one, each is a different aspect of the personality. The depressed individual suffers from a depression of his spirit. The condition of the depressed person is: He is unable to respond. But when properly understood and handled, the depressive reaction can open the way to a new and better life. The patient needs to get in touch with his feelings, his inner being, This, in turn, helps him regain a measure of self-possession and independence. In the process it reorients him to the personal self. When successful, it finishes by restoring an individual's faith in himself, if he is to overcome his depressive tendency.

Grounding in Reality

The signs of elation are not difficult to discern. The elated person is hyperactive, his speech is more rapid, his ideas seem to flow freely, and his self-esteem is conspicuous. Further development of this phenomenon leads to the condition of mania. "The triumphant character of mania arises from the release of energy bound in the depressive struggle and now seeking discharge." In the depressed state the ego is tied to the collapsed body, having been overwhelmed by feelings of hopelessness and despair. It struggles to get free, and when it does, it rises triumphant like a gas balloon released from the hand of a child, becoming steadily more inflated as it goes upward. There is an increase of excitation in the manic condition, but this increased excitation or energetic charge is limited to the head and to the surface of the body, where it activates the voluntary muscular system producing the characteristic hyperactivity and exaggerated volubility. This direction of flow, upward rather than downward, does not lead to discharge, which is a function of the lower end of the body. It serves instead to focus attention on the individual and represents an attempt to restore the sense of infantile omnipotence that was prematurely lost.

The elated state is only a lesser degree of this reaction. The ego of the elated individual is also overexcited, as if in anticipation of some extraordinary or miraculous event that would realize the person's deepest desire. The hope of restitution, generally unconscious, provides the motivation for the upward swing of energy, which results in elation. But as her elation grows, people are disturbed by it and withdraw. To be fulfilled is to be filled full, and that means a full belly whether of good food or good feelings. Everyone seeks something like this, the surrender and letting go, but few have the faith that would allow it to happen.

The Energy Dynamics of Depression

Depression is a loss of an organism's internal force comparable in one sense to the loss of air in a balloon or tire. Desperation, depression, and despair are forms of living death which are often intolerable to bear.

Depression is a form of dying, emotionally and psychologically. The depressed person not only has lost his zest for life but has temporarily lost the will to live. He has, to the degree of his depression, given up on life.

Depression is marked by the loss of energy. The depressed person complains of lack on energy, and most observers agree the complaint is valid. Even in the less depressed person there is a noticeable dimimution in spontaneous gestures and a visible lack of facial change.

The Psychoanalytic View of Depression

In a paper entitled "Mourning and Melancholia," published in 1917 by Freud, there was a parallel between mourning and melancholia (as the state of depression was then called). Both have many traits in common; "a profoundly painful dejection, abrogation of interest in the outside world, loss of the capacity to love, inhibition of all activity." *In depression or melancholia the ego is undermined by the energetic collapse of the body, resulting in an unalive and unresponsive condition.

Freud noted that "in grief the world becomes poor and empty, in melancholia it is the ego itself" that becomes poor and empty.

But while it is true that in depression the ego is severely deflated, we should not regard depression as a purely psychic reation. If we do, we focus on the ego to the exclusion of the body and fail to see how depression affects the total personality. Depression is a loss of feeling, and Freud concluded in his article "that melancholia consists in mourning over loss of libido." Since libido is the psychic energy of the sexual drive, it can be equated with sexual feeling and, therefore, with excitement in general. To put it in physical terms, the melancholic person mourns the loss of his aliveness. Anyone in contact with a depressed person is aware he is constantlly bemoaning his lack of feeling, interest, and desire. In effect, the depressed person has suffered a loss of self, not just self-esteem. I believe that the only real treatment for depression is to enlarge the meaning of life by increasing the pleasure of life. What an adult can grieve for is the loss of his full potential as a human being. Libido describes the force behind any striving for pleasure. According to Jung, "it is the energy or motive force or striving as derived from the primal or all-inclusive urge to live." In other words it is the force behind the spirit of man.

Freud had defined libido as "that force by which the sexual instinct is represented in the mind." *But in another context he also described the libido as "the force by which the sexual instinct expresses itself." Thus on one hand the libido is seen as a pure mental force while on the other it is regarded as a physical one.

Wilhelm Reich took up the question of the actual neuroses at the point where Freud abandoned it. Knowing that anxiety was a somatic symptom, Reich realized that it could be caused only by a physical dysfunction, that is, by some disturbance of the sexual function on the body level. This meant that in every neurosis in which anxiety is present, as it is in all the psychoneuroses, there must also be some sexual disturbance. Thus where Freud and the other analysts emphasized only the psychic factors in the neurosis, Reich showed the importance of the somatic. If the sexual excitation is not fully discharged, whether for psychic or other reasons, there will be an "accumulation of tension" and the individual will experience anxiety. It followed logically that if full discharge occured, there could be no anxiety. Since a neurosis without anxiety is meaningless, the neurosis itself would disappear in the presence of full sexual satisfaction.

Reich confirmed this hypothesis both in his work with patients and in his observations of people. Individuals who experienced full orgastic satisfaction showed no signs of neurotic behavior, and patients who gained this satisfaction as a result of their analysis lost all signs of their neurotic affliction. Reich also found that only those patients who were able to maintain this capacity for full orgastic discharge remained free from their neurotic disturbances. This insight led him to formulate the principle that the function of the orgasm *was to discharge all the excess energy or excitation in the organism, and thus maintain emotional health by preventing an accumulation of tensions.

With this principle, the breakthrough to the body was possible. Sexual excitation on the somatic level was no different from the same excitation in the psychic realm. Every psychic conflict had its counterpart in a corresponding physical disturbance, and the corollary of this was also true. Mind and body were not separate entities but two aspects of an individual's being. Their relationship to each other was expressed in the concept of psychosomatic identity and antithesis. They were both equally charged by the same excitation, yet each could infuence the other.

They lead also to another very important conclusion, namely, that the libido or sexual excitation is not a mental phenomenon; it is a real physical force or energy. This conclusion is supported by a number of observations. First, we all know that there are different intensities of sexual excitation. These differences cannot be explained physiologically but only by the assumption that they represent different amounts of libidinal charge or catharsis of the genital apparatus. Second, the libidinal charge or energy can invest other organs and raise their level of excitation - the lips, the nipples and even the anus. Through this excitement these organs gain an erotic quality similar to that in the genitals. Third, any diminution of the energy level of the organism as in depression reduces the libidinal charge. Fourth, only genital excitation gives the idea of sex its sense of tension or urgency. Without an accompanying genital charge the idea of sex is impotent.

Seen as a physical force or energy, the libido cannot be limited to sexuality. It must be conceived as a life energy in general, as Jung hypothesized. It is available for all the needs of the organism, libidinal or aggressive, motoric or sensory. Both the pathway and the outlet determine the nature of the drive and the feeling. When it flows upward toward the head end of the organism, it generally leads to actions whose function is to increase the energy charge of the organism. For example, the arms reach out to hold and take, the mouth reaches to suck and swallow. When the flow is downward, it leads to discharge activities of which sex is the best example.*

The body maintains a balance between energy intake and energy output. We expend energy in movement and discharge it in sex. The amount available for sexual discharge is the excess over what is used in maintaining the living process. Reich postulated that it was the function of the sexual orgasm to discharge this excess energy, which in its pathway to the genital outlet is experienced as sexual excitation. The total discharge of this excitation or energy is experienced as a full orgasm, deeply satisfying and immensely pleasurable. A partial discharge like a partial bowel evacuation lacks this feeling of full satisfaction. The undischarged excitation or energy becomes a disturbing force in the body. It has no place to go and no means of getting out. It may even excite the heart, producing palpatations, or the belly, resulting in butterfly sensations. It is known as free-floating anxiety. It is also the basis for guilt feelings, since the lack of satisfaction leaves the individual feeling bad, which becomes translated into wrong or guilty.

Life may be viewed as an excitatory phenomenon. We are not ordinary pieces of clay but a substance that has been infused with spirit or charged with energy. When we become more excited, our energy level rises. When we become depressed, it falls. If we become highly excited, we light up or luminate and glow. These excitatory phenomena like sexual excitement are energetic processes. And the lumination or glow that they produce can be seen. Many people have seen it.

There is an energy field about the human body that has been variously described as an aura or glow. It has been observed and studied by many people. Dr. John C. Pierrakos said: The "energies within the body also flow out of the body in the same manner as a heat wave travels out of an incandescent metal object." *When a person stands against a homogenous background, either very light (sky) blue or very dark (midnight) blue, and with certain arrangements so that there is a softness and uniformity in the light, one can see with the naked eye or more clearly with the aid of colored filters (cobalt blue) a most thrilling phenomenon. "From the periphery of the body arises a cloud-like, blue-gray envelope which extends for 2 to 4 feet where it losses its distinctness and merges with the surrounding atmosphere. It swells slowly, for 1 or 2 seconds, away from the body until it forms a nearly perfect oval shape with fringed edges. It remains in full development for approximately ¼ of a second and then, abruptly, it disappears completely. It takes about 1/5 to 1/8 of a second to vanish. Then there is a pause of 1 to 3 seconds until it reappears again, to repeat the process. This process is repeated 15 to 25 times a minute in the average resting person."

This rate of pulsation appears to be independent of any other known bodily rhythm such as respiration and heartbeat. It varies, however, with the overall degree of bodily excitation.

"The field reflects the level of excitation and the intensity of feeling in the body. It seems to have some relation to the autonomic or involuntary responses of the body. One observes different color changes in the outer layers of the field that correspond to different emotions. Soft feelings of love produce a soft rose color. Sadness produces a dark blue hue in the field over the chest. Anger or rage results in a dark red color in the field over the back and shoulders. A golden glow may be seen over the head when the expression of feeling is forthright and sincere. There is a depression of the whole field phenomenon in states related to pain due probably to the action of the sympathetic adrenal system in withdrawing blood from the surface of the body."* The depression of the energy field is even more marked in people who are suffering from a depressive reaction

Since the field reflects the energetic processes that are operative in the organism, it can be used to diagnose disturbances in body functioning. In the field of a schizophrenic person, for example, there are characteristic distortions such as interruptions of the field and color changes, which a trained observer can recognize. This aspect of the field phenomenon is more fully discussed in Dr. Pierrakos' articles. (John C. Pierrakos, The Rhythm of Life, monograph)(New York, The Institute for Bioenergetic Analysis, 1966),(P.32.)

The energy field is not a subjective fact like a body sensation. It has an objectivity in that different observers report the same visual phenomena. An individual in a state of intense pleasurable excitement may feel that he is glowing; he doesn't see the glow, but others can. If he feels radiant, the radiation from his body is observable. In fact under proper lighting conditions almost anyone can see the field phenomenon. One of the easiest ways to do this is to hold the hands about one foot from the eyes with the palms turned inward against a light-blue sky. If the hands are relaxed and the fingertips held about one inch apart, the pulsatory glow about the fingers is readily visible. For some people, however, it may take a llttle time until their eyes are relaxed enough to pick up the phenomenon.

The human being is not the only organism that has an energy field. All living organisms manifest this property. There is a visible energy field about trees,* which could be the basis for the animistic belief that a tree possesses a spirit. The same phenomenon can be observed over mountains, ocean water, and crystals.

The energy charge within the organism is responsible for its energy field. I have mentioned that these energy fields extend 2 to 4 feet from the body. That is not a fixed limit. In some cases they are seen to extend for many times that distance. This in many situations we are exposed to and in contact with the energy fields of other people. When the fields are in contact, they glow more strongly. People can excite each other, but they can also depress each other. A vibrant person with a strong field has a positive influence on other persons around him. Knowledge, itself, is a surface phenomenon and belongs to the realm of the ego. One has to feel the flow and sense the course of the excitation in the body. To do this, however, one must give up the rigidity of one's ego control so that the deep body sensations can reach the surface. This sounds easier than it is, for the control is established to prevent this from happening. Neither the neurotic nor the schizoid individual is prepared to let life take over. He is too frightened of the consequences, specifically, of the feeling of helplessness that develops when power and control are surrendered.

To surrender, one must have certain qualities, but this element is lacking in some people. Yet living on the surface only is relatively meaningless, and so all people want to break through the barrier. If no other way is available, they will use alternative methods to gain some contact, even monentarily, with their inner being.

Letting go of ego control means giving in to the body in its involuntary aspect. It means letting the body take over. But this is what patients cannot do. They are afraid that if the body takes over it will expose their weakness, demolish their pretentiousness, reveal their sadness, and vent their fury. Yes, it will do that. It will open a new depth of being and add a richness to life compared to which the wealth of the world is a mere trifle. This richness is a fullness of the spirit.

These considerations force us to look at the issues dialectically and in energetic terms. Every impulse can be viewed as a wave of excitation that begins at some center in the organism and flows along a designated path, which is its aim, toward an object in the external world, which is its goal. But it is also true that every impulse is an expression of the human spirit, for it is the spirit that moves us. However the spirit doesn't move us only in one direction. Impulses flow upward toward the head, the feeling has a spiritual quality. We feel uplifted and excited. The downward flow has a sensuous or carnal quality, since this direction brings the charge into the belly and toward the earth, giving us the feeling of being relaxed, rooted and released.

Human life pulsates between its two poles, one located in the upper or head end of the body, the other in the lower or tail end. We can equate the upward movement with a reaching toward heaven, the downward movement with a burrowing into the earth. We can compare the head end with the branche's and leaves of a tree, the lower end with its roots. Because the upward movement is toward light and the downward one toward darkness, we can relate the head end with consciousness and the lower end with the unconscious. For more detailed information about this see book.

F Key Saver

(bioenergetic training workshops)

F Key Saver

"Leon Salzman, M.D."

Copyright 1985, 1980

Freud's formulation was related to the libido theory and stated that depression was the result of the loss of an ambivalent loved object. He felt that the individual introjected the lost object and that the hostility manifested in this disorder resulted from the expression of the person's feeling toward the hated aspects of the lost object. This interpretation was useful in explaining many observable manifestations of the depressive reaction, both neurotic and psychotic. It emphasized the elements of hostility and the loss of a valued object, which resembled the process of mourning.

The concept of depression presented here proposes that depression is a reaction to a loss and a maladaptive response in attempting to repair the loss. It is not seen as a disease but as a potential in all personality structures when a loss is experienced as leaving one totoally helpless and impotent. It is in this respect that its relationship to the obsessional mechanism is manifested, and it is under these circumstances that the obsessional mechanisms break down because of internal or external stresses.

A variety of defensive responses may occur in the wake of a failing obsessional defense - for example, schizophrenia, paranoid developments, and other grandiose states, as well as depression. At present it is extremely difficult to determine why one response occurs and not another. However, it is clear that the depressive reaction is commonplace because the obsessional mode of behavior is universal. The depressive reaction may be mild or severe, with the same wide spectrum. When it occurs in the normal obsessional or in those with any other neurotic disorder or personality type, it is the failure of the obsessional defense to maintain the standards or values considered by the individual to be essential. Depression follows the conviction or apprehension that the value, person, or thing deemed necessary may actually be lost or no longer available.

These values or persons are not necessarily realistic nor are the demands reasonable. They are invariably extreme and excessive and form part of the obsessive neurotic value system in which the requirements for perfection and omniscience are essential ingredients. While the obsessional system is intact, the illusion of omniscience and perfection can be maintained. However, a crises, or some unexpected event may stir up the individual's apprehension about his ability to maintain these standards. If the concerns continue and the apprehension becomes a conviction, depression may supervene.

From the adaptational point of view (without recourse to earlier theories), depression is a reparative process which supervenes when a person feels he has lost something vital to his phychic integration. The reaction of despair and depression is the result of the anticipated rebuff and the expectation of total rejection as a consequence of this loss. With this framework in mind, the other elements in depression become more understandable. The hostile, demanding, and clinging behavior is related to this desperate attempt to regain the lost object from those felt to be responsible for taking it away or capable of restoring it. The depressed person pleads, begs, demands, cajoles, and attempts to force the environment to replace or restore the object.

If depression is related to the obsessive dynamism, the responsiveness of depressions to physiological therapies must also be accounted for. Because electric shock therapy and drug convulsants produced effects which either injured the patient or made him fearfully resistive, he viewed such treatment as punishment. This attitude coincided with the theory of depression which implied that such people are guilty and self-destructive. Shock therapy was viewed as relieving the superego of its harshness, permitting the depression to be resolved. This is an appealing view, even though the insulin therapies (unlike metrazol and ECT) are neither painful nor distressing. Too, the use of tranquilizers, psychic energizers, and placebos - which produce little or no distress yet prove valuable - casts serious doubts on such an interpretation. It has never been clearly established where the value of such dissimilar physiological approaches lies. The tranquilizing drugs, with their mildly euphoric effect. and the psychic energizers, which improve the patient's physical condition, are also beneficial in the treatment of depressive states.

Concise Guide to Mood Disorders

Steven L. Dubovsky, M.D.

Amelia N. Dubovsky, B.A.

Unipolar and Bipolar Mood Disorders

One of the most important distinctions between mood disorders is the distinction between unipolar and bipolar categories. Unipolar mood disorders are characterized by depressive symptoms in the absence of a history of a pathologically elevated mood. In bipolar mood disorders, depression alternates or is mixed with mania ("unipolar mania") are given the diagnosis of bipolar mood disorder, on the assumption that they will eventually have an episode of depression.

Understanding Depression

Patricia Ainsworth, M.D.

Symptoms of Depression

There is no blood test for depression yet. The diagnosis is based on the reports of sufferers about how they feel and on observations of how they look and behave made by doctors and by people who know them well.

The symptoms of depression fall into four categories: mood, cognitive, behavioral, and physical. In other words, depression affects how individuals feel, think, and behave as well as how their bodies work. People with depression may experience symptoms in any or all of the categories, depending on personal characteristics and the severity and type of depression.

Depressed people generally describe their mood as sad, depressed, anxious, or flat. Victims of depression often report additional feelings of emptiness, hopelessness, pessimism, uselessness, worthlessness, helplessness, unreasonable guilt, and profound apathy. Their self-esteem is usually low, and they may feel overwhelmed, restless, or irritable. Loss of interest in activities previously enjoyed is common and is usually accompanied by a diminished ability to feel pleasure, even in sexual activity.

As the illness worsens, the cognitive ability of the brain is affected. Slowed thinking, difficulty with concentration, memory lapses, and problems with decision making become obvious. Those losses lead to frustration and further aggravate the person's mounting sense of being overwhelmed. The sufferer longs for escape, and thoughts of death intrude, sometimes taking the form of wishful thinking, as in "I wish God would just take me" or "I wish I could vanish," and often involving ideas of suicide.

In its most severe forms, depression causes major abnormalities in the way sufferers see the world around them. They may become psychotic, believing things that are not true or seeing and hearing imaginary people or objects.

Psychosis in depression is not rare. between 10 and 25 percent of patients hospitalized for serious depression, especially elderly patients, develop psychotic symptoms. Symptoms of psychosis may include delusions (irrational beliefs that cannot be resolved with rational explanations) and hallucinations (seeing, hearing, feeling, tasting, or smelling things or people that are not present). People with psychosis may develop paranoia, believing that they are being manipulated by known or unknown people or forces, that there is a conspiracy against them, or that they are in danger. No amount of rational explanation changes the delusional belief. Others may be convinced that they have committed an unpardonable sin against loved ones or against their God and deserve severe punishment, even death. Some sufferers become so firmly convinced of their own worthlessness that they begin to view themselves as a burden to their families and choose to kill themselves. Occasionally, severe depression may result in hallucinations in which the depressed person hears or sees things or people that are not present; other types of hallucinations, such as smelling or feeling things that are not present, are less common in severe depression than in some other brain disorders.

The changes occurring with depression understandably result in alterations in behavior. Most individuals with moderate - to - severe depression will experience decreased activity levels and appear withdrawn and less talkative, although some severely depressed individuals show agitation and restless behavior, such as pacing the floor, wringing their hand, and gripping and massaging their foreheads. Given a choice, most begin to avoid people and activities, yet others will be most uncomfortable when alone or not distracted. In general, the severely depressed become less productive, although they may successfully mask the decline in performance if they have been highly productive in the past. In the workplace, depression may result in morale problems, absenteeism, decreased productivity, increased accidents, frequent complaints of fatigue, references to unexplained aches and pains, and alcohol and drug abuses. Severely depressed individuals have been known to work their regular schedule during the day, interact with their coworkers in a routine way, and then go home and kill themselves.

Depression is more than a mental illness. It is a total body illness. People suffering from moderate - to - severe depression experience changes in their body functions. Their energy levels fall, and they fatigue more easily. Insomnia is common and takes many forms; depressed individuals may have difficulty going to sleep or experience early morning awakenings. A subgroup of depressed patients feel an excessive need for sleep. Depressives consistently complain that their sleep is not restful and that they feel just as tired in the morning when the awake as they did when they went to bed the evening before. Some may be troubled by dreams that carry the depressive tone into sleeping hours, causing abrupt awakenings due to distress. Appetite changes are common. Physical complaints are common and may or may mot have a physical basis. Physical complaints of depressed patients cannot be overlooked, because many studies inicate an increased risk of real physical illness in people who have severe forms of depression. The reasons for this are unclear.

Types of Depression

Bereavement

Bereavement, or grief, is a normal feeling of sadness that occurs following the loss of a loved one. Uncomplicated grief is believed to advance through a series of stages that, in many aspects, mimic the illness depression, raising questions as to where normal bereavement ends and major depressive illness begins. For further breakdown of this, see book.

Adjustment Disorder with Depression

Adjustment disorder with depression is the term for the condition commonly referred to as situational depression or reactive

depression. Individuals with this malady feel sadness about a loss or major life change. The sadness, depressed mood, or sense of hopelessness begins within three months of a major stress and is excessive. People with this form of depression may find it difficult to carry on routine activities at home, at work, or at school. The depression gradually disappears once the stress is over and is not usually considered a serious depression, although it may be very uncomfortable. Often the support and advice of concerned friends, loved ones, or a doctor are enough to help sufferers manage until their mood improves following removal of stress or a decrease in it's intensity.

Dysthymic Disorder

Some depressions are chronic and can last a lifetime. Dysthymic disorder, or dysthymia, describes a more chronic condition in which individuals experience depression for most of the day, most of the time, for at least two years. Brief periods of relatively normal mood may intervene, but those periods of relief last no more than a couple of months at a time. Depression of this type may last for years, even a lifetime. Dysthymic disorder is chronic but not usually severe, yet it may cause significant problems in everyday life.

Major Depressive Disorder

Major depressive disorder (also known as unipolar depression or clinical depression) is the serious and often disabling form of depression that can occur as a single episode or as a series of depressive episodes over a lifetime. The course of major depressive disorder is variable. A single episode may last as little as two weeks or as long as months to years. Some people will have only one episode with full recovery. Others recover from the initial episode only to experience another one months to years later. There may be clusters of episodes followed by years of remission. Some individuals have increasingly frequent depressive episodes as they grow older.

During major depressive episodes. sufferers will have most, if not all, of the depressive symptoms affecting the mood, cognitive, behavioral, and physical aspects of life. The most severe forms of major depressive disorder may result in delusions and the other psychotic abnormalities described earlier in this chapter. This is one of the most disabling forms of depression.

Bipolar Disorder

Bipolar disorder is a so-called "mood swing disorder" formerly known by the more familiar term "manic-depressive illness."