INTERVIEW

WITH PATRICK THE LAMA

A: I got into the Beatles at an early stage, around age 12-13.

This was right around when John Lennon was shot in 1980, which led to a

lot of new Beatles books and articles in the newspapers. Of all the great

Beatles records, it was the psychedelic stuff that really knocked me over,

things like "Tomorrow never knows" and "It's all too

much". Many of my friends liked the Beatles too, but they thought the

acid-inspired tracks were just too weird! After the Beatles I got into Bob

Dylan, and after that it was the Byrds, the Doors, Velvet Underground,

Neil Young, and so on. Along with some friends we went through the great

60s music, layer after layer. Then in the mid-1980s, the neo-garage

explosion happened, and for us in Stockholm the timing was perfect. We had

been through the famous 1960s music, and needed something new. So

compilation LPs like Pebbles and Back From The Grave, along with fanzines

like Kicks and Ugly Things, opened up a whole world for us. It was really

exciting. We dressed up like 60s "garage" bands, with moptop

haircuts, paisley shirts, Chelsea boots, etc. That whole style was new

then -- it was created in the mid-1980s. There were cool bands here in

Stockholm, like the Stomachmouths and the Crimson Shadows, who were all

friends of mine. Each weekend we'd get drunk, watch our friends play, and

party all night. The skinheads wanted to beat us up, so you had to watch

your back! The garage scene lasted for about 3 years, after that it

started feeling "old", and there was also a silly dogmatic

attitude among some garage people (especially in the USA) that you could

only like certain types of music, and that you should hate Jimi Hendrix

and Black Sabbath, etc. Well, we liked Hendrix and Sabbath, and so we

broke off from the fundamentalist neo-garage scene. Around this time, some

of us started taking LSD instead of booze and amphetamines, and this

changed everything. Now we began to understood the old psychedelic records

for REAL. There was an acid scene going here circa 1987-1992, which led to

some cool neo-psych LPs like St Mikael and Word Of Life, with many former

garage guys involved. Another important thing is that we discovered the

American "private press" LP scene, thanks mostly to a New York

record dealer named Paul Major, who mailed out catalogs with rare records

that were like nothing we had seen before. Paul Major is perhaps the

single most important person for re-discovering the whole

"private" and "local" music scenes of the 1960s-1970s.

The Acid Archives book is basically an extension of what he did in the

late 1980s and early 1990s. So after our LSD trips and Paul's catalogs, my

mission was clear, and that's what is still happening with the Acid

Archives book and website.

Q: What's the origin, the aim and the message of the

Acid Archives book ? What is the difference between this book and some

other bibles dedicated to the field, such as Fuzz Acid & Flowers ?

A: The basic philosophy behind the Acid Archives book is that you don't

have to be famous to create great rock music. The mainstream "rock

critics" of the 1970s-1980s failed to understand one very important

thing about rock music, which is that success and fame has very little to

do with quality. For each band that got lucky, like the Rolling Stones,

there were a dozen other bands who created music that was just as good and

talented, but who weren't in the right place and right time to be

discovered. Rock music is a terribly unfair business -- you can be an

outstanding talent, but if your timing is one year off, or if you live in

a small town far away, you're not going to be discovered. In the USA,

during the 1960s-1970s, many talented and dedicated artists wanted to get

their music released anyway, even if no record label was interested, and

so they put it out themselves as a limited "private" or

"vanity" release. In Europe these type of releases were common

during the 1970s punk era, but otherwise they're not common, and it's

mainly an American phenomena. There were many 1000s of outstanding

"private press" albums put out at the time in USA and Canada.

One great advantage of these records is that the artist didn't have to

compromise with the record label, because there was no record label! In

other words, the music came out exactly as the artists wanted it, which is

not what you get on a major label, mainstream release, where the record

label and manager and everyone else is trying to "improve" or

commercialize the music. So, the Acid Archives book is about this gigantic

underground of music by unknown people, some of whom were outstanding

talents, and who just were unlucky. "Fuzz Acid & Flowers" is

great for the famous and semi-famous 1960s bands, but it works in a

traditional way, from the top and downwards. Our Acid Archives book turns

the pyramid upside down, by starting at the bottom with all the unknowns

and their often amazing music.

Q: You indicate in the introduction of your book

that there will never be a final word on the subject when it comes to

unbury obscur 60s-70s garage / psych albums. Do you really think there's

still classics waiting to be discovered, after 25 years of intense

research and knowledge dedicated to the mid-60s by collectors, reissue

labels, etc…?

A: Yes and no. The great wave of re-discovery of private press LPs and

artists was in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Back then it was pretty

amazing, because each month there would be dozens of previously unknown

killer LPs discovered; albums that were truly great and mindblowing. Today

they're classics, like Fraction or the Bachs. At the same time the scene

was much smaller then, it was mainly a concern for a few hundred record

collectors in the US, Europe and Japan. Today there's 1000s of young

people who love these unusual old LPs, and are trying to find more. And

since the USA and Canada are such huge countries, there are still

1960s-1970s albums popping up today, that were previously unknown. I would

even say that there's more great albums being discovered today than it was

5-6 years ago, because the field is so hot right now. During 2006 alone, I

must have heard at least 15 old albums that I would call truly great, and

that were unknown to exist a few years ago. Right now, "downer

folk" and "outsider" albums from the 1970s are very hot --

this is personal and often scary albums by mentally unstable guys, a bit

like Syd Barrett's solo LPs, or Alexander Spence's "Oar". There

are 100s of such albums, and they have aged well, since they're so

personal and emotionally deep.

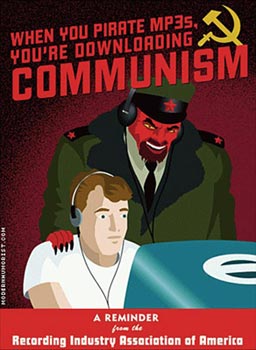

Q: The P2P phenomenon has been a revolution for the communities of 60s

music lovers. Everybody has now an unlimited access to tons of music thru

emule, dozens of blogspots, or thru home-made comps offered for free on

various forums. What's your opinion about that and its potential impact on

the reissue market?

A: I have mixed feelings about this. My usual comment regarding both

bootleg reissues and P2P is that you have to look at each individual case.

If someone puts up "Dark side of the moon" on P2P it doesn't

really hurt anyone. However, if you put up a recent CD reissue of an

obscure album made by a small independent label, you're stealing sales

directly from that label. That's the way it is. I don't really believe

that people buy more records after downloading whole albums. If someone

wants to help people decide what to buy, you put up either 1 entire song

from the album, or 60-second clips of 3-4 songs. That's what I do. There

is no reason to upload an entire album, unless you're out to

"share" the whole thing, which is basically a generous form of

theft. The small reissue labels are the ones that drive the whole

retrospective music underground, and knocking the legs out from under them

is obviously a bad idea. If they go bankrupt, there will be no

"cool" CD reissues to upload in a few years. The other thing to

consider is uploading rips of rare LPs that haven't yet been reissued.

Again, if you want people to decide if they're interested in them, take

60-second clips of a few songs. If the album has been going round on P2P,

no label may want to reissue it, and again everyone loses -- the band, the

reissue labels, and the music fans who don't get to hear the album in

re-mastered format, with unreleased material, liner notes etc. This

process is happening as we speak, and a lot of small labels are hurting

from it, as well as some artists who never get to see the royalties they

deserve. People need to use their judgment and think about what they're

doing. What's the point of hurting an artist and label whose music you

like?

Q: You're also known as a 60s garage comp

connoisseur, all classic comps being featured and reviewed on your "Age

Of Madness" web page. What's your opinion of the current overflow of

new garage comps that showed up recently on the market ? Is the old belief

that only 80s seminal comps such as Off the Wall, Chosen Few and such are

the best that ever came out still true, or have you noticed some

incredible comps that showed up those last years / months and that you

would recommend ? Is there plans for a new edition of the Age of Madness

book ?

A: There will definitely not be a new "Age Of Madness", as the

combination of the "Soybomb" database (at the Ugly Things

website) and Mike Markesich's coming garage discography is much more

complete and accurate than my old book. I had fun doing that project,

which was my first book, but none of it has been updated since the late

1990s, not even the website. The compilation reviews are the only things

that remain unique. Regarding the recent comps, I think it's unfortunate

that the garage guys have moved so fearlessly into the CD field, because

60s garage music and the CD format don't combine well, in my opinion. I've

actually sold almost all my CD garage comps, after transferring the best

tracks to my harddisk. These recent comps have very little

"soul" or personality, unlike the great old 1980s vinyl comps

like Chosen Few or Back From The Grave. I still have all the old ones,

they're outstanding comps, most of them. There's a reason why new CD comps

of 60s garage barely sell 300 copies, while the old vinyl comps from the

1980s go for upwards $100 on eBay. Of course, things were easier back

then, because those guys could choose from 1000s of great garage 45s,

while today there's maybe only 100 really strong garage 45s left to

reissue. The garage comp series that I see going today and which does it

the right way is "Diggin' For Gold".

Q: I have the feeling that you're not that

much into what's not American when talking about 60s music. I've read

somewhere that your interest for UK psych stopped with the outcome of the

Rubble comps, that were disappointments to you. What's your opinion and

level of lovin with the non US 60s scenes ?

A: I started out with the British 60s bands, as most young music-lovers

do. I still love a lot of it, and the only reason I haven't worked more on

the British stuff is that once you've processed the top two layers, it

gets a bit difficult to find good, unknown music from the UK. The British

retro scene has always been very well taken care of -- the first

Merseybeat comp came as early as 1974, and it's still the best one. The

killer mod-psych stuff like Wimple Winch and Factory was already

well-known in the early 1980s, and was covered by terrific comps like

Chocolate Soup and Perfumed Garden. When "Rubble" came out, I

loved the first two volumes, which had lots of previously unknown 45s, but

after that the series seemed to get weaker and weaker. The thing I noticed

about "Rubble" was that on each volume, the best tracks were

always the repeats, the ones that had already been out on Choc Soup and

Perfumed Garden. The "new" stuff tended to be weaker, and some

of it I have to say was pretty awful, mediocre frilly-shirt pop. I took

this as a sign that the British 60s underground was already scraping the

bottom of the barrel around 1986-87, and in retrospect I think this turned

out to be correct, with a few exceptions. This was one of several reasons

why my main allegiance switched from the UK to the US at that point. It's

too bad there isn't more, but England is a smaller country than the US,

and most importantly the "local" and "private"

releases were much fewer. It was mostly a major label scene. It's possible

to get a grasp on the whole British 60s scene, from the Beatles down to

David John & the Mood, in maybe 3 years. For American 60s music, it

takes 15-20 years, or forever. However, I would still say that the best

British 60s records are as good as anything I've ever heard. As for other

countries, I think the Netherlands and Australia produced outstanding 60s

music that could be considered world-class scenes, which I know fairly

well.

Q: What do you think of the type of compilations and

retrospective releases that are happening nowadays? Do you see any

problems there?

A: I would definitely agree that the "complete recordings" type

reissues is a bad development. On many occasions, these old 60s bands had

maybe 4-5 good originals to offer, 2-3 good covers, and the rest fillers.

That is still OK over the span of a 40-minute LP, such as the classic Eva

sampler of We The People that you mentioned. When you add everything the

band recorded, the only thing that happens is that you lower the average

musical quality of the band, and it makes no one happy. I'm generally not

very interested in unreleased material, unless it's really good. To

include unreleased material, it has to RAISE the average quality of the

sampler album -- in other words, the previously unheard things must be at

least as good as the band's known releases, to be included. Unfortunately,

very few labels follow this principle, and the CD format has made the

situation much worse. If I were to put together a sampler reissue, I would

think of the listener first and last, and would rather give them 40

minutes of excellent listening, than 75 minutes of terribly uneven

listening. Noone has the patience to program their CDs, that is an option

that never became popular with people. I'm tired of CD releases of 70+

minutes playtime, it's hardly ever worth hearing the whole thing. This is

another reason why I think reissues and compilations were better back in

the 1980s than they are today. The things that are better today is the

sound quality and legality, but these are less important than the musical

experience for the buyer.

Q: Here's what can be read on a Bam Caruso release

(Koobas LP): "A message from Bam Caruso: the enjoyment of this record

can be significantly marred by the consumption of so-called mind-expanding

substances - so remember : Don't take drugs!" What's your point of

view about that? Do you drop acid to enjoy the psychedelic experience at

full level ?

A: Most people who do LSD and other mind-expanding drugs find after a

while that the trip takes them to a certain point, but not beyond. To go

beyond that, or to maintain the experience permanently, many go on to

spiritual practices such as Tibetan buddhism, natural highs, and so forth.

I've studied and experimented with those things, and it's obvious that

there's a tradition of ancient wisdom that lies very close to what western

man in the 20th century discovered via LSD. It would be fun to do

psychedelics again, and I in fact have a list of certain LPs that I want

to try in that altered state, music we didn't know about back when we were

tripping a lot. So for that reason it would be fun, but it's no big deal

if I do it or don't. I think the psychedelic experience is very important,

and in the hands of adult, emotionally mature people it can improve their

lives in a profound, positive way. Unlike the sad Bam Caruso people I've

found that a lot of music sounds even better in a lysergic state. Not

everything works, but sometimes the change is remarkable. Koobas is

perhaps not a band that I would listen to on acid, because they weren't a

psychedelic band. American westcoast music usually works very well, and we

also used to listen to "acid punk" from 1966-67 quite a bit when

tripping -- things like the Psychedelic Disaster Whirl compilation sounds

incredible then.

Q: Maybe a few words about the 13th Floor Elevators,

and the place they occupy in your life ? What's the story behind you and

them ?

A: Yeah, the 13th Floor Elevators have a special place in my life. I

spent 5 years researching them, and have published a book on them,

"The Complete Reference File" from 2002. The Elevators were

unique in many ways; they combined intellectual elements and rock'n'roll

elements in a manner that only Dylan and Velvet Underground have matched.

The most important thing to realize about the Elevators is that to them it

wasn't a "game", or a "career" -- the fire-breathing

psychedelia heard on their records is how they lived their lives, every

day. They believed 100% in what they were doing; not in some goofy

flower-power way, but via an elaborate, intellectual paradigm which was

developed by their lyricist and jug player, Tommy Hall. I think Tommy Hall

is one of the most brilliant people to ever get involved with rock'n'roll

-- it's just pure luck that he chose rock music, rather than becoming a

high-brow poet, or philosophy graduate student. Putting him in the same

band as an outstanding vocalist and songwriter like Roky, and a terrific

lead guitarist like Stacy Sutherland, was one of the luckiest combinations

of the 1960s. I've always liked the Elevators, but it was after getting

into psychedelic drugs that I started examining them more closely, and the

more you found out about them, the more amazing the story became. At the

same time, most of what had been written over the years was goofy and

incorrect, mainly silly rock'n'roll "myths" about Roky. So I saw

the need of getting the Elevators story straight and remove some of the

lies and hype, and that was my motivation for writing that book. I have a

CD-Rom of the whole Elevators book available for sale via my website, by

the way.

Q: It seems that your love for psychedelism gets

wider than the 60s frontiers and that you enjoy also some other kinds of

music such as goa / trance ? is that right ? What are the other scenes,

from the past and of today, that interest you ? We know that you've been

deeply into the mid-80s Swedish garage explosion, but do you still keep an

eye on the current underground garage scene ? Or the current acid-folk

revivalists (Espers, Josephine Foster, Jose Gonzales, etc) ?

A: Although I was involved in two retro-music "scenes", the neo-garage wave of the mid-1980s and the modern psych wave on the Xotic Mind label of the early 1990s, I'm somewhat skeptical of "scenes". My theory is that truly great, contemporary music does NOT come out of a scene, but out of unknown artists and bands working by themselves, in a vacuum. Take a look at the first Bevis Frond album, "Miasma", which I'd rate as one of the very best modern psych LPs from anywhere. At the time, there was no Bevis or Woronzov "scene", it was just Nick Salomon putting together a private press release of things he'd been working on at home. Many years of living, writing and DIY stubborness went into it, and for that reason it sounds very real. Bevis would make some more pretty good LPs, but the whole "scene" that sprung up around the band and the label produced almost nothing else of value -- it was just the same old neo-psych with overblown guitar solos. I think this is the way it works -- the truly great albums being made right now do not come from "hip" bands that belong to a "scene", but to loner visionaries sitting in basements and thinking up things noone else has. Bobb Trimble's "Harvest Of Dreams" from 1982 is another example -- not only does it blow all modern psych to smithereens, but it's actually as good as the original late 60s psych stuff. And Bobb wasn't "neo" anything, he didn't look hip or know the right people, he was just an unknown small-town guy trying to capture what was in his mind. I've been through so many hyped up underground neo/retro scenes, and so much of it is just lame, the same old desire to become a rock star and not having to work a real job. I never liked the Fuzztones much, if you know what I mean. As for current psychedelia, an album that has caught some attention of late is the Valley Of Ashes, a 3-LP set from a rural commune US band who play basement drone psychedelia, and are far removed from any urban hipster rock clubs. So again, that's kind of typical -- the Valley Of Ashes hits a spot that the underground trend bands miss. However, I'm sure there are some pretty good neo/retro bands out there in garage, psych and folk-land. If anything is truly worthwhile, it will survive, and I will put it in the 7th Edition of the Acid Archives book in 2016 (ha-ha).

Q: On your website and blog you mention Goa Trance

on occasion...?

A: Yeah, I love Goa, or Psychedelic Trance. For me, that is the most

relevant form of modern psychedelia. Dance music really became influential

around 1988-89, and after that I believe a lot of the most talented young

people have moved into techno, ambient, hip-hop, drum & bass etc,

rather than to "rock" music. What happened with Goa is that the

circle was finally closed; the kids who started out with ecstasy and acid

house went on to LSD, and began making dance music that was geared towards

acid trips, more than Ecstasy trips. So it was acidheads making music for

acid trips, which is precisely what you had in the late 1960s. I recognize

a lot of the moods and ideas in PsyTrance from original 60s psychedelia --

it's upbeat and positive, it's mysterious, it's very drug liberal, it's

creative, it aims for beauty and bliss. The original 1980s Detroit techno

was nihilistic, minimalist and bleak, and the mid-1990s Goa Trance was

almost the perfect opposite of that. Acid house was OK, but like old

school disco it's music that works much better on a club dance-floor. At

home it may sound monotonous and simplistic. Goa Trance on the other hand

sounds very good at home, the louder, the better. I have something like 40

original comps of Goa Psytrance from 1994-97, and the average quality of

the music is very high. I sort of stopped following neo-garage in the late

1980s, but I'm very glad to see that the scene is still happening, and

obviously big bands like the White Stripes wouldn't have existed without

the first garage retro wave. Neo-garage is now a permanent genre within

rock music, which I think is great. I must admit I'm not well informed of

the contemporary folk scene. I know the names, but I haven't heard much of

it yet. It seems interesting, and the pagan element gives an intellectual

aspect that is respectworthy.

Q: Can you enlighten us about the everyday life of a specialist of your

kind ? It seems that you have a regular job, married with 2 kids, and have

many other interests in life apart music. Now, how does an apparently

normal guy as you become a specialist of your kind ? And how do you

manage to combine a pricey and timeconsuming hobby such as record addiction

and family life?

A: I decided early on that I would try to separate my main interest

(music) from my professional career (as an IT consultant). The reason for

this was partly that it's very hard to make good money in the field of

underground music, and I got tired of being short on money when I was a

college student. The main reason though, was seeing the guys who worked

professionally with music, such as record dealers. There were some record

stores that I visited every week as a teenager, and I got to know the guys

working there, and who were almost exactly like what you find in the

"High Fidelity" book and movie. I assumed that these guys had

once loved music as much as I did, but after working with it every day for

20 years, they seemed burned out and bitter and gave the impression they

hated almost all the records they were handling. It was pretty funny, but

also a little scary, and I made a conscious decision when I was 18-19 NOT

to become like that. This plan has worked out pretty well for me, although

I must admit I spend a lot of time at my "white collar" job

thinking about music and records, checking eBay auctions, corresponding

with people in the US and around Europe and so on. In recent years, I've

been able to cut back on my "square" work-hours a bit, and spend

more time on music and writing, which is great. Achieving this balance has

hopefully kept me a bit more sane than the guys who decide that record

collecting is their life -- because it can never be a full life. As for

the family situation, my wife is a great music fan, and our tastes overlap

in many areas (such as Bobby Fuller, the Kinks and Velvet Underground),

although she can't stand some of the weirder stuff, like Yahowha 13. So I

have a good pair of Sennheiser headphones for that kind of records! My

music acquisitions are about equally divided between original pressings

from the 1960s-1970s, CD/vinyl reissues, and CD-R trades. I don't download

or fileshare at all, I don't really like the concept and prefer something

I can put my hands on, instead of just a digital cloud. CD-R trading has

been important for the Acid Archives book, because many of the albums are

so obscure that you can look for years to find just 1 copy. I like

old-school CD-R trading between two guys, like people used to trade tapes

earlier. I think that is a great way to check out music, and it's not

something that may damage the artist or record labels, unlike file-sharing.

Regarding rare originals, I have a want list that I'm working on, and I

buy maybe 4-5 really rare and valuable albums per year. I'm actually

buying more originals now than I did 5 years ago -- working on the book

made me remember how fun it was to hunt down vinyl originals as a

teenager.

Patrick The Lama in his acid-free disguise

Q: What are the latest records that really impressed

you ? What's on your turntable currently ?

A: Some current favorites include the recent, first-ever legit reissue of

Mighty Baby's "Jug Of Love", the best Dead-style "rural

rock" LP ever from England. I've loved this LP for many years, and

it's great to see it finally getting the attention it deserves. Everyone

knows Mighty Baby's debut LP but "Jug Of Love" is even better in

my ears. I'm writing a review of this for the next Ugly Things issue.

Another one I'm planning to review is Wildfire, an outstanding

guitar-psych/hardrock LP from Southern California 1970, which wasn't even

known to exist until the 1990s. It's now out on a legit CD reissue from

the band, who I was in contact with last year. Like so many old

underground bands, they're amazed that people today even know who they

are. The Wildfire LP is one of the 10 best ever in its genre. Apart from

this, I've been listening to a lot of 1950s jazz lately, the westcoast

cool-jazz which I think is great. Gerry Mulligan, Stan Getz, Dave Brubeck,

things like that. Jazz doesn't have to be this advanced free-form avant

stuff that developed in the 1960s -- prior to that jazz meant something

else, which is a sophisticated, easily accessible music that has aged very

well. I'm also listening to crooners, which is great for Christmas. Nat

King Cole's "Classic Collection" is probably the single record

I've played most times the last month.

Q: What other psych resources on the web would you

recommend, apart Psychedelica and the garage punk forums ?

A: The knowledge and connections are spread out across a number of useful

forums and websites. I spend a lot of time at eBay and popsike.com.

There's a forum called Soulstrut which is huge and covers much more than

just "record collector" fields -- there's DJ's and crate diggers

and writers and all kinds of people. It's a good place for the typical

white European "rock" record collector to get into what's going

on in 2007, while still keeping a connection to his field of

specialization. There's a British folk forum called "New Bruton

Town" which is pretty cool. There's a Yahoo forum for "West

Coast Psychedelia" that has a lot of knowledgable people. Everything

is kind of spread out and fragmented, but I think that's good -- it helps

keeping it alive and changing, in the typical Internet way.

END

A French language version of this interview has been published in the Dig

It! magazine, issue #49, Spring 2007. Here is Dig

It! magazine