|

|

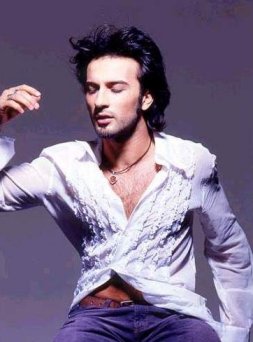

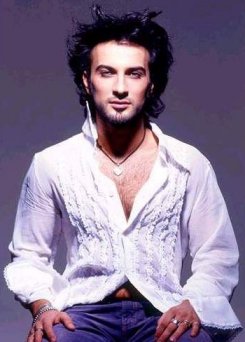

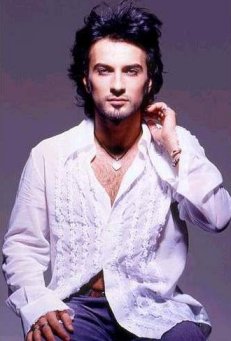

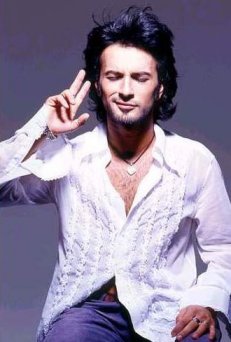

Pop Music's Young TurkTarkan's got the Look and the Moves -- and His Eye on the U.S.

This article was published in Washington Post newspaper (USA) on November 18, 2001.

The Middle Eastern Elvis: An English-language Tarkan album is planned for release next year, with a U.S. tour projected for early 2003. David Segal/Washington Post Staff Writer -ISTANBUL- The avuncular, bushy-browed founder of modern Turkey gazes from every coin and nearly every corner of this exotic and ancient city. Kemal Ataturk -- literally "father of the Turks" -- is beloved here for booting colonialists out of the country and dragging the frayed remnants of the Ottoman Empire into the 20th century. On the streets of Istanbul, his image is about as hard to avoid as kebabs and strong coffee. For decades, nobody in this country of 66 million laid claim to such a wide slice of the national psyche. But Ataturk now has some competition: a 29-year-old with day-old stubble who can tummy-flutter like a belly dancer. Turkey is gaga for Tarkan, the This summer Tarkan released his fourth album, "Karma," and it seemed to pour from every car radio and restaurant in the nation, echoing through resort towns along the Mediterranean coast and out of dozens of Istanbul's zooming Fiat taxis. Tarkan's bright green eyes beamed from billboards selling everything from Pepsi to Nokia phones, and he had a lock on the covers of every one of the celebrity glossies. For an American analogy, think Elvis circa 1957, the last time an entire country was besotted with -- or, among tradition-bound parents, outraged by -- a single performer. "He's got the whole market to himself," says Michael Lang, Tarkan's manager. "There is nobody else here." Now there's talk of bringing Tarkan to the United States. Ahmet Ertegun, the Turkish-born impresario who was a founder of Atlantic Records and helped guide the careers of Aretha Franklin, Otis Redding and Led Zeppelin, among others, has for years been looking for a backable Turkish artist and will soon begin collaborating with Tarkan on an English-language album. A rough schedule slates the album for release next year, with a U.S. tour in early 2003. "I saw him perform in Turkey and I thought he was one of the best live performers I've ever seen," Ertegun said in a recent phone interview. "He's a great dancer, he moves beautifully, and he has the magic that all big hit artists share, which is the ability to get an emotion across through a recording." But the attacks of Sept. 11 may disrupt the plans of Tarkan as well as a few dozen other Muslim performers planning U.S. tours. No other realm of the music business has been as devastated by terrorism as that of Middle East pop, a niche genre that was starting to get some traction in the United States. Advocates were betting that it could do for countries like Egypt what "Buena Vista Social Club," a collection of Havana jazz artists, had done for Cuba. The week of the attacks, a handful of Middle Eastern performers were getting ready to board planes for a long-scheduled and mostly sold-out 10-city tour of the States, including a stop in Washington. Among the performers: an Egyptian star named Hakim and an Iranian-born singer named Andy. Those shows were immediately canceled and it's unclear if they'll be rescheduled. "These are bands that play great dance music, but do people want to dance at a concert now, especially an Arab concert?" said Miles Copeland, the veteran manager who helped organize the tour. "A lot of people were excited about this. It's incredibly disappointing."

For the time being, Tarkan will focus on Turkey and the rest of Europe, where his super-emotive dance-pop, sung in Turkish and infused with Middle Eastern drums and guitars, is huge. The 1997 single "Simarik" wound up atop the French charts, and more than a million copies of Tarkan's last album were shipped to Denmark. He's the largest-selling non-Russian pop star in Russia. That makes him the first cultural export from Turkey to find a mass audience, which is why many here regard him as more than just a singer. He's considered the country's best shot at shattering a strangely enduring stereotype: Turkey as a land of mustachioed brutes. That caricature was pasted on by Hollywood courtesy of 1977's "Midnight Express," the gripping but brazenly racist account of a young American's escape from a Turkish prison. The film, based on a true story, set back the tourist industry here by about a decade, and the search for a pop-culture force powerful enough to present the modern, human face of this country -- the one tourists have been raving about for years -- has been underway ever since. Tarkan just might be that force. A few years ago the government even considered officially designating him the nation's "cultural ambassador," though there weren't enough pro-Tarkan votes in Parliament to pass the resolution. Tarkanmania has its limits, even here. The Turkish Elvis, it turns out, knows a thing or two about scandalizing the elderly. "I'm in a little depressing mood today," Tarkan says in nearly a whisper. "I was just in my bedroom all day, watching movies." It's early September, a week before the World Trade Center and Pentagon attacks, and Tarkan is sitting on a sofa set up on the mossy grounds of Rumeli Hisari, a 15th-century fortress poised on the banks of the Bosporus. In an hour, he'll play in the fortress's mid-size amphitheater. Tankers are floating downstream on a waterway that divides the European and Asian sides of Istanbul. The moon rises over the Asian mountains. This must be the most picturesque "backstage" on the planet. Tarkan turns out to be surprisingly small, about 5 1/2 feet in sneakers, and his teeth are glowingly white, his eyes a contact-lens shade of green. He's one of those remarkably adorable people who seem to flirt just by looking in your eyes and speaking softly. In a few minutes, he'll go through his pre-show routine, which includes a 30-minute massage and some voice exercises. For the moment, he's reclining on the sofa, sipping espresso and looking pooped. He spent the day in his apartment, in part because walking the streets is out of the question. On a recent visit to the capital city of Ankara, even normally staid bureaucrats mobbed him. "It gets worse and worse. I love it, but I have no life," he sighs in lightly accented English, smiling wearily and running a hand through his hair. "People grab me and kiss me. I like that, but it can be overwhelming." For a few weeks this summer, it was worse than overwhelming. In April, Turkish tabloids ran photos of Tarkan, stolen by a furniture mover, in the loving embrace of a man. Tarkan has firmly refused to comment, but the episode provoked gales of is-he-or-isn't-he speculation and an untidy debate in Turkey about the morality of homosexuality. One right-wing politician denounced him as an assault on the nation's morals, and there were predictions that Tarkan's career was over. Fans, however, were unmoved.

"You'll see from my audience tonight, they don't care," said Tarkan. "And I don't care what people think. This is my life. I know who I am. I stood up for my rights and my life. Instead of feeling guilty about anything, I felt mad. I feel better now." It has all made for irresistible fodder for magazines. One, Hafta Sonu, ran a cover story on Tarkan with the headline "Is Tarkan a Satanist?" The story picked apart the cover of his latest album, with a helpful annotation for anyone looking for clues to the artist's links to the Devil. "This is ridiculous," says Tarkan, when asked to translate some of the copy. "But maybe it sells magazines." Without a doubt it sells music, and the music -- an East-meets-West blend of Ottoman rhythms and Euro beats -- says a lot about Turkey, a country that has one foot in the modern world, one in the ancient, one eye on the Orient and the other set enviously on the West. The not-so-secret power of this nominally democratic country is the military, which ruthlessly separates mosque and state and has banned Muslim fundamentalist parties wherever they gain momentum. The tactics have been denounced as heavy-handed -- or worse. But whatever its shortcomings, Turkey's odd hybrid government has allowed it to tilt decisively toward the the West in matters both political (Turkey is the only Muslim country to send soldiers to Afghanistan) and cultural (there are far more tank tops than veils in Istanbul). You can trace this bias straight to Ataturk, the charismatic, hard-drinking soldier and statesman who was so dead set on modernizing Turkey that he outlawed the fez, the brimless red hat that facilitates Muslim head-to-the-ground prayer. For a while, wearing a fez in Turkey could get you shot; these days, they're found mostly in tourist gift shops. That is why Tarkan could happen here, but not in another country that's 90 percent Muslim. "We're opposed to Islamic fundamentalism," said Ahmet Ertegun, who spoke from a New York hospital where he is recovering from heart surgery. "It's not illegal to buy a drink in Turkey." For Ertegun, Tarkan is only the latest battle in a decades-long campaign to highlight Turkey's secular side, a cause that runs through Ertegun's veins. His father fought alongside Ataturk in the war of independence, and later moved to Washington to serve as Turkey's ambassador to the United States. The younger Ertegun -- who met Ataturk briefly as a child -- moved with his family to Washington as a teen, and would eventually relocate to Manhattan to form Atlantic Records, where he helped popularize rhythm and blues while his brother Nesuhi developed the label's jazz roster. But as he produced albums for Aretha, Ray Charles and the Drifters, he kept an eye out for a Turkish singer who could project, through music, the face of Turkey that his father and Ataturk promoted through diplomacy and law.

"All the countries in the world are trying to develop a kind of international image that makes them attractive to tourism, and music can do a lot in that regard," Ertegun says. "The bossa nova craze created an incredible amount of new tourism to Brazil. A country like Turkey is thought of as a faraway, difficult kind of place. Tarkan could help the country establish an image of a young, free-thinking democratic people." When Tarkan released his first album in 1993, he offered exactly what teens here had long wanted but couldn't find -- music that's a little bit oriental and a little bit rock-and-roll. He felt both familiar and foreign for good reason. Growing up, Tarkan digested plenty of Ottoman classical music thanks to his parents, and he'd fallen hard for artists as diverse as Abba and Elvis thanks to Germany, where he was born and lived until he was 13. Somewhere along the line, he learned the art of infuriating his detractors in a way that bonds him to his fans. By U.S. standards, the bar for outrageous behavior is set pretty low in Turkey, and Tarkan keeps stumbling right into it. In 1994, he brushed off a post-show interview request on live television by muttering the now-infamous line "Cisim var, agbi," which translates roughly to "I gotta pee, man," before sauntering off camera. In Turkey, where decent manners are required of the young, the comment was considered flippant and galling. Only when he performed traditional songs on another TV special did he endear himself again to the nation. A few years later he loudly refused to serve in the military, opting to live in New York rather than serve the 18 months required of every male adult, or face arrest. That's a no-no in a land with an emphatic sense of nationalism, and it prompted calls to strip Tarkan of his citizenship. While his contemporaries donned uniforms, he spent two years in Manhattan, learning English at Baruch College. He returned home only after the Turkish government, strapped for cash following the catastrophic 1998 earthquake, sliced the service time to 28 days for anyone willing to hand over the equivalent of USD$16,000. With a comet's trail of photographers to document the moment, Tarkan showed up at boot camp and spent a month in fatigues. "It was January and snowing like crazy," says Tarkan. "It was tough; the food was terrible." A longer tour of duty was out of the question. "Eighteen months of my life for nothing? I thought my own dreams were more important." The draft-dodging controversy didn't hurt Tarkan's sales, nor did the controversy about his love life. Tarkan's biggest problem, it turns out, is wide-scale piracy. For every album he's sold, says manager Lang, an illegal copy has been made and sold on the streets. "It's a mom-and-pop industry, the way the U.S. was in the '50s and '60s," says Lang, a man best known for promoting the first Woodstock concert in 1969. He first visited Turkey in the late '70s, fell in love with the place and has returned every few years. He heard Tarkan during a visit and decided he'd stumbled onto something huge. All that Lang lacks now is the proper machinery to manufacture fame. "You talk to anyone here about mechanicals" -- the royalties paid whenever a song is played -- "and they look at you funny," Lang says, standing near the Rumeli Hisari stage. He adds, "We need an RIAA," the U.S. record industry trade association that watches over copyrights. "An RIAA with guns."

In the coming weeks "Karma" will be released in 50 countries, including the United States. But the U.S. charts are generally inhospitable to anyone speaking a foreign language, and Tarkan isn't expected to make inroads here until that English-language album is released. Ertegun is hoping that producer Mutt Lange, who has worked with AC/DC and Shania Twain, will be interested. "I'm not worried" about anti-Muslim prejudice, he said. "If you have a hit song, it doesn't matter what country you're from. Music makes its own way." There's no telling what the 2,000 fans at Rumeli Hisari would do if they got their hands on Tarkan, but you sense he'd wind up in the hospital. The music throughout this 2 1/2-hour show comes from a 14-piece band, leaning heavily on a pair of synthesizers, a few Turkish drums and a plinky Middle Eastern guitar called the oud. Tarkan smiles, sings and slithers like a genie, with a special emphasis on his belly, which he bares with come-hither coquettishness at one point, pulling up his shirt and somehow quivering his stomach at about six quivers per second. A Ricky Martin comparison is inevitable; the difference is that Tarkan's moneymaker is his abs instead of his rear end. Love is his topic of choice. On "Kuzu, Kuzu" he begs forgiveness for his flings and promises to follow a lover around like a sheep: "Your absence is too hard / I couldn't get used to it / Bang bang this foolish head / On the walls / Throw it against the rocks for the joy of it / Then forgive me, come home." He sings his new hit single, twice, blows some kisses and disappears. As the crowd files out, the scene looks utterly Western; the audience is skewed toward teenage girls but filled with plenty of 40- and 50-year-olds. They leave, exhausted and smiling. "We believe, in the future, he'll be very famous," says Cem Sariza, a fan who is standing near the fortress gates at the end of the show. "He could the next Michael Jackson. We love him a lot."

Who is Tarkan? | His Music | How I knew about him | What's New | Links | Home © 2002 - El Palacio de Tarkan |

country's first international pop star.

country's first international pop star.