2

The

Project

Management

Context |

Projects and project management

operate in an environment broader than that of the

project itself. The project management team must

understand this broader context—managing the

day-to-day activities of the project is necessary for

success but not sufficient. This chapter describes key

aspects of the project management context not covered

elsewhere in this document. The topics included here are:

2.1 Project Phases and the Project Life

Cycle

2.2 Project Stakeholders

2.3 Organizational Influences

2.4 Key General Management Skills

2.5 Socioeconomic Influences

|

2.1

Project

Phases

and the

Project

Life Cycle |

Because projects are unique undertakings, they involve a

degree of uncertainty. Organizations performing projects

will usually divide each project into several project

phases to provide better management control and

appropriate links to the ongoing operations of the

performing organization. Collectively, the project phases

are known as the project life cycle.

2.1.1 Characteristics of Project Phases

Each project phase is marked by completion of

one or more deliverables. A deliverable is a

tangible, verifiable work product such as a feasibility

study, a detail design, or a working prototype. The

deliverables, and hence the phases, are part of a

generally sequential logic designed to ensure proper

definition of the product of the project.

The conclusion of a project phase is generally marked by

a review of both key deliverables and project performance

in order to (a) determine if the project should continue

into its next phase and (b) detect and correct errors

cost effectively. These phase-end reviews are often

called phase exits, stage gates, or kill

points. Each project phase normally includes a set of

defined work products designed to establish the desired

level of management control. The majority of these items

are related to the primary phase deliverable, and the

phases typically take their names from these items:

requirements, design, build, text, start-up, turnover,

and others as appropriate. Several representative project

life cycles are described in Section 2.1.3.

2.1.2 Characteristics of the Project Life

Cycle

The project life cycle serves to define the beginning

and the end of a project. For example, when an

organization identifies an opportunity that it would like

to respond to, it will often authorize a feasibility

study to decide if it should undertake a project. The

project life cycle definition will determine whether the

feasibility study is treated as the first project phase

or as a separate, stand-alone project.

The project life cycle

definition will also determine which transitional actions

at the end of the project are included and which are not.

In this manner, the project life cycle definition can be

used to link the project to the ongoing operations of the

performing organization. The phase sequence defined by

most project life cycles generally involves some form of

technology transfer or hand-off such as requirements to

design, construction to operations, or design to

manufacturing. Deliverables from the preceding phase are

usually approved before work starts on the next phase.

However, a subsequent phase is sometimes begun prior to

approval of the previous phase deliverables when the

risks involved are deemed acceptable. This practice of

overlapping phases is often called fast tracking.

Project life cycles generally define:

- What technical work

should be done in each phase (e.g., is the work

of the architect part of the definition phase or

part of the execution phase?).

- Who should be

involved in each phase (e.g., concurrent

engineering requires that the implementors be

involved with requirements and design).

Project life cycle

descriptions may be very general or very detailed. Highly

detailed descriptions may have numerous forms, charts,

and checklists to provide structure and consistency. Such

detailed approaches are often called project management

methodologies. Most project life cycle descriptions share

a number of common characteristics:

- Cost and staffing

levels are low at the start, higher towards the

end, and drop rapidly as the project draws to a

conclusion. This pattern is illustrated in Figure

2–1.

- The probability of

successfully completing the project is lowest,

and hence risk and uncertainty are highest, at

the start of the project. The probability of

successful completion generally gets

progressively higher as the project continues.

- The ability of the

stakeholders to influence the final

characteristics of the project product and the

final cost of the project is highest at the start

and gets progressively lower as the project

continues. A major contributor to this phenomenon

is that the cost of changes and error correction

generally increases as the project continues.

Care should be taken to

distinguish the project life cycle from the product

life cycle. For example, a project undertaken to

bring a new desktop computer to market is but one phase

or stage of the product life cycle.

Although many project life

cycles have similar phase names with similar work

products required, few are identical. Most have four or

five phases, but some have nine or more. Even within a

single application area there can be significant

variations—one organization’s software

development life cycle may have a single design phase

while another’s has separate phases for functional

and detail design.

Subprojects within projects may also have distinct

project life cycles. For example, an architectural firm

hired to design a new office building is first involved

in the owner’s definition phase when doing the

design and in the owner’s implementation phase when

supporting the construction effort. The architect’s

design project, however, will have its own series of

phases from conceptual development through definition and

implementation to closure. The architect may even treat

designing the facility and supporting the construction as

separate projects with their own distinct phases.

2.1.3 Representative Project Life Cycles

The following project life cycles have been

chosen to illustrate the diversity of approaches in use.

The examples shown are typical; they are neither

recommended nor preferred. In each case, the phase names

and major deliverables are those described by the author.

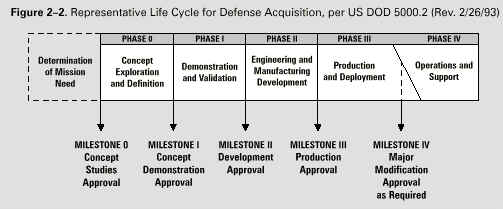

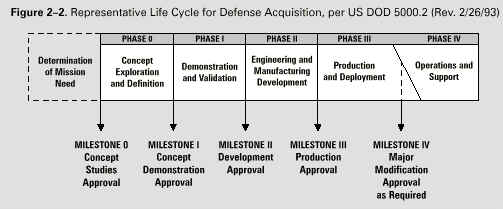

Defense acquisition. The U.S. Department of

Defense directive 5000.2, as revised February 1993,

describes a series of acquisition milestones and phases

as illustrated in Figure 2–2

- Determination of

Mission Need—ends with Concept Studies

Approval.

- Concept Exploration

and Definition—ends with Concept

Demonstration Approval.

- Demonstration and

Validation—ends with Development Approval.

- Engineering and

Manufacturing Development—ends with

Production Approval.

- Production and

Deployment—overlaps ongoing Operations and

Support.

Construction. Morris

[1] describes a construction project life cycle as

illustrated in Figure 2–3:

- Feasibility—project

formulation, feasibility studies, and strategy

design and approval. A go/no-go decision is made

at the end of this phase.

- Planning and

Design—base design, cost and schedule,

contract terms and conditions, and detailed

planning. Major contracts are let at the end of

this phase.

- Production—manufacturing,

delivery, civil works, installation, and testing.

The facility is substantially complete at the end

of this phase.

- Turnover and

Start-up—final testing and maintenance. The

facility is in full operation at the end of this

phase.

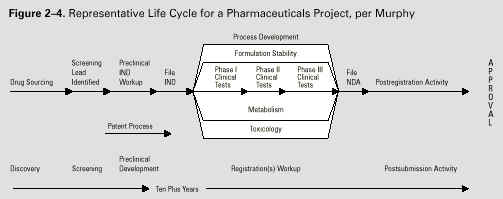

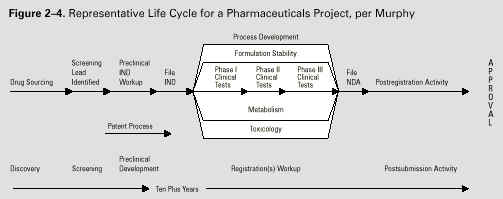

Pharmaceuticals. Murphy

[2] describes a project life cycle for pharmaceutical new

product development in the United States as illustrated

in Figure 2–4:

- Discovery and

Screening—includes basic and applied

research to identify candidates for preclinical

testing.

- Preclinical

Development—includes laboratory and animal

testing to determine safety and efficacy as well

as preparation and filing of an Investigational

New Drug (IND) application.

- Registration(s)

Workup—includes Clinical Phase I, II, and

III tests as well as preparation and filing of a

New Drug Application (NDA).

- Postsubmission

Activity—includes additional work as

required to support Food and Drug Administration

review of the NDA.

Software development. Muench,

et al. [3] describe a spiral model for software

development with four cycles and four quadrants as

illustrated in Figure 2–5:

- Proof-of-concept

cycle—capture business requirements, define

goals for proof-of-concept, produce conceptual

system design, design and construct the

proof-of-concept, produce acceptance test plans,

conduct risk analysis and make recommendations.

- First build

cycle—derive system requirements, define

goals for first build, produce logical system

design, design and construct the first build,

produce system test plans, evaluate the first

build and make recommendations.

- Second build

cycle—derive subsystem requirements, define

goals for second build, produce physical design,

construct the second build, produce system test

plans, evaluate the second build and make

recommendations.

- Final

cycle—complete unit requirements, final

design, construct final build, perform unit,

subsystem, system, and acceptance tests.

|

2.2

Project

Stakeholders |

Project

stakeholders are individuals and organizations who

are actively involved in the project, or whose interests

may be positively or negatively affected as a result of

project execution or successful project completion. The

project management team must identify the stakeholders,

determine what their needs and expectations are, and then

manage and influence those expectations to ensure a

successful project.

Stakeholder identification is often especially difficult.

For example, is an assembly line worker whose future

employment depends on the outcome of a new product design

project a stakeholder? Key stakeholders on every project

include:

- Project

manager—the individual responsible for

managing the project.

- Customer—the

individual or organization who will use the

project product.

- There may be multiple

layers of customers. For example, the customers

for a new pharmaceutical product may include the

doctors who prescribe it, the patients who take

it, and the insurers who pay for it.

- Performing

organization—the enterprise whose employees

are most directly involved in doing the work of

the project.

- Sponsor—the

individual or group within the performing

organization who provides the financial

resources, in cash or in kind, for the project.

In addition to these there

are many different names and categories of project

stakeholders—internal and external, owners and

funders, suppliers and contractors, team members and

their families, government agencies and media outlets,

individual citizens, temporary or permanent lobbying

organizations, and society at large. The naming or

grouping of stakeholders is primarily an aid to

identifying which individuals and organizations view

themselves as stakeholders. Stakeholder roles and

responsibilities may overlap, as when an engineering firm

provides financing for a plant it is designing. Managing

stakeholder expectations may be difficult because

stakeholders often have very different objectives that

may come into conflict. For example:

- The manager of a

department that has requested a new management

information system may desire low cost, the

system architect may emphasize technical

excellence, and the programming contractor may be

most interested in maximizing its profit.

- The vice president of

research at an electronics firm may define new

product success as state-of-the-art technology,

the vice president of manufacturing may define it

as world-class practices, and the vice president

of marketing may beprimarily concerned with the

number of new features.

- The owner of a real

estate development project may be focused on

timely performance, the local governing body may

desire to maximize tax revenue, an environmental

group may wish to minimize adverse environmental

impacts, and nearby residents may hope to

relocate the project.

In general, differences

between or among stakeholders should be resolved in favor

of the customer. This does not, however, mean that the

needs and expectations of other stakeholders can or

should be disregarded. Finding appropriate resolutions to

such differences can be one of the major challenges of

project management.

|

2.3

Organizational

Influences

|

Projects are typically

part of an organization larger than the

project—corporations, government agencies, health

care institutions, international bodies, professional

associations, and others. Even when the project is the

organization (joint ventures, partnering), the project

will still be influenced by the organization or

organizations that set it up. The following sections

describe key aspects of these larger organizational

structures that are likely to influence the project.

2.3.1 Organizational Systems

Project-based organizations are those whose

operations consist primarily of projects. These

organizations fall into two categories:

- Organizations that

derive their revenue primarily from performing

projects for others—architectural firms,

engineering firms, consultants, construction

contractors, government contractors, etc.

- Organizations that

have adopted management by projects (see

Section 1.3).

These organizations tend

to have management systems in place to facilitate project

management. For example, their financial systems are

often specifically designed for accounting, tracking, and

reporting on multiple simultaneous projects.

Non–project-based organizations—manufacturing

companies, financial service firms, etc.—seldom have

management systems designed to support project needs

efficiently and effectively. The absence of

project-oriented systems usually makes project management

more difficult. In some cases, non–project-based

organizations will have departments or other sub-units

that operate as project-based organizations with systems

to match.

The project management

team should be acutely aware of how the

organization’s systems affect the project. For

example, if the organization rewards its functional

managers for charging staff time to projects, the project

management team may need to implement controls to ensure

that assigned staff are being used effectively on the

project.

2.3.2 Organizational Cultures and Style

Most organizations have developed unique and

describable cultures. These cultures are reflected in

their shared values, norms, beliefs, and expectations; in

their policies and procedures; in their view of authority

relationships; and in numerous other factors.

Organizational cultures often have a direct influence on

the project. For example:

- A team proposing an

unusual or high-risk approach is more likely to

secure approval in an aggressive or

entrepreneurial organization.

- A project manager

with a highly participative style is apt to

encounter problems in a rigidly hierarchical

organization, while a project manager with an

authoritarian style will be equally challenged in

a participative organization.

2.3.3

Organizational Structure

The structure of the performing organization

often constrains the availability of or terms under which

resources become available to the project. Organizational

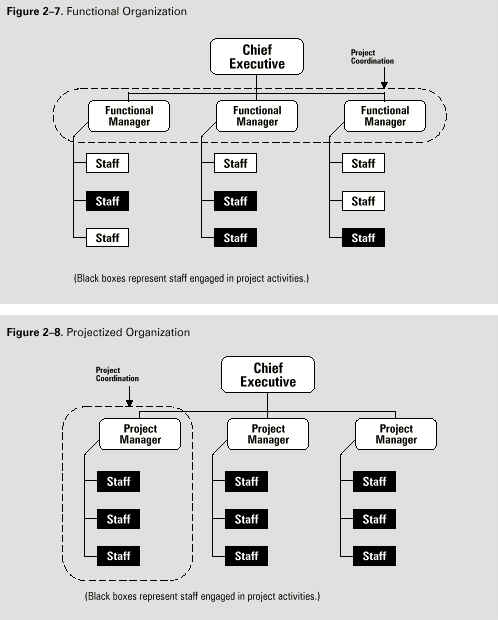

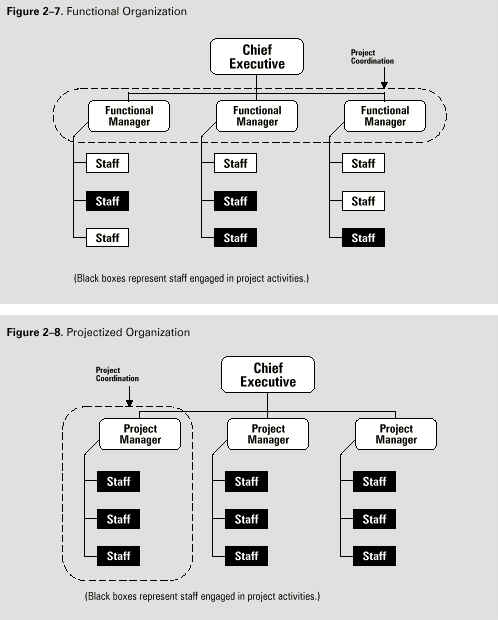

structures can be characterized as spanning a spectrum fromfunctional

to projectized, with a variety of matrix

structures in between.Figure 2–6 details key

project-related characteristics of the major types of

enterprise organizational structures. Project

organization is dis-cussed in Section 9.1, Organizational

Planning. The classic functional organization shown

in Figure 2–7 is a hierarchy where each

employee has one clear superior.

Staff are grouped by specialty, such as production,

marketing, engineering, and accounting at the top level,

with engineering further subdivided into mechanical and

electrical. Functional organizations still have projects,

but the perceived scope of the project is limited to the

boundaries of the function: the engineering department in

a functional organization will do its work independent of

the manufacturing or marketing departments. For example,

when a new product development is undertaken in a purely

functional organization, the design phase is often called

a "design project" and includes only

engineering department staff. If questions about

manufacturing arise, they are passed up the hierarchy to

the department head who consults with the head of the

manufacturing department. The engineering department head

then passes the answer back down the hierarchy to the

engineering project manager.

At the opposite end of the spectrum is the projectized

organization shown in Figure 2–8. In a

projectized organization, team members are often

collocated. Most of the organization’s resources are

involved in project work, and project managers have a

great deal of independence and authority. Projectized

organizations often have organizational units called

departments, but these groups either report directly to

the project manager or provide support services to the

various projects.

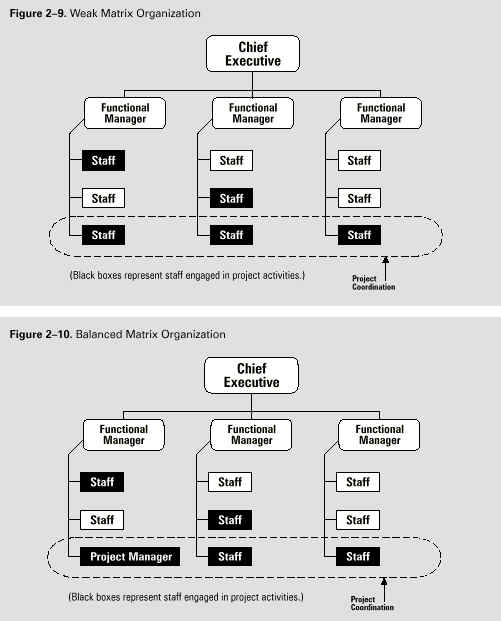

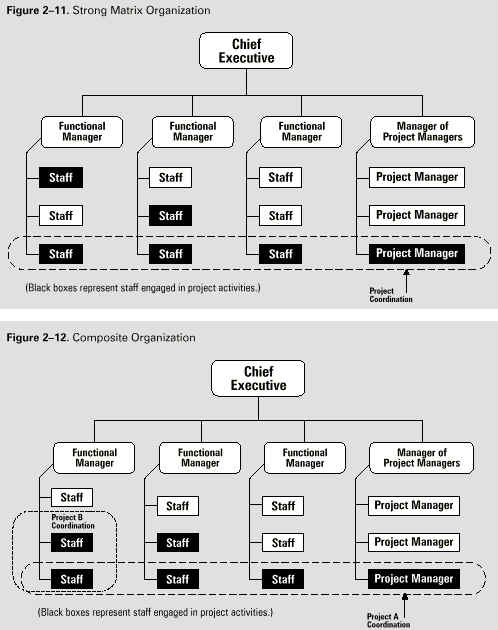

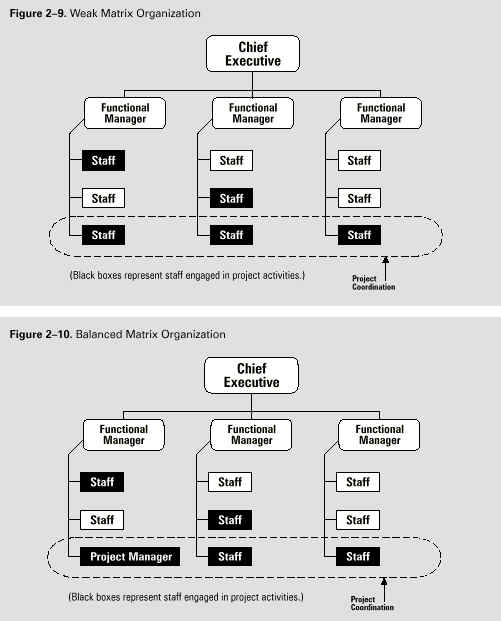

Matrix organizations as shown in Figures

2–9 through 2–11 are a blend of

functional and projectized characteristics. Weak matrices

maintain many of the characteristics of a functional

organization and the project manager role is more that of

a coordinator or expediter than that of a manager. In

similar fashion, strong matrices have many of the

characteristics of the projectized

organization—full-time project managers with

considerable authority and full-time project

administrative staff.

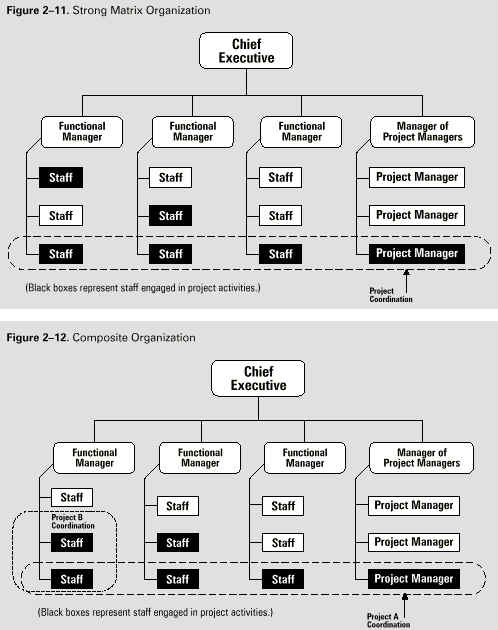

Most modern organizations involve all these structures at

various levels as shown in Figure 2–12. For

example, even a fundamentally functional organization may

create a special project team to handle a critical

project. Such a team may have many of the characteristics

of a project in a projectized organization: it may

include full-time staff from different functional

departments, it may develop its own set of operating

procedures, and it may operate outside the standard,

formalized reporting structure.

|

2.4

Key

General

Management

Skills

|

General management is a broad subject dealing

with every aspect of managing an ongoing enterprise.

Among other topics, it includes:

- Finance and

accounting, sales and marketing, research and

development, manufacturing and distribution.

- Strategic planning,

tactical planning, and operational planning.

- Organizational

structures, organizational behavior, personnel

administration, compensation, benefits, and

career paths.

- Managing work

relationships through motivation, delegation,

supervision, team building, conflict management,

and other techniques.

- Managing oneself

through personal time management, stress

management, and other techniques.

General management skills

provide much of the foundation for building project

management skills. They are often essential for the

project manager. On any given project, skill in any

number of general management areas may be required. This

section describes key general management skills that are highly

likely to affect most projects and that are not

covered elsewhere. These skills are well documented in

the general management literature and their application

is fundamentally the same on a project.

There are also many general management skills that are

relevant only on certain projects or in certain

application areas. For example, team member safety is

critical on virtually all construction projects and of

little concern on most software development projects.

2.4.1 Leading

Kotter [4] distinguishes between leading and managing

while emphasizing the need for both: one without the

other is likely to produce poor results. He says that

managing is primarily concerned with "consistently

producing key results expected by stakeholders,"

while leading involves:

- Establishing

direction—developing both a vision of the

future and strategies for producing the changes

needed to achieve that vision.

- Aligning

people—communicating the vision by words and

deeds to all those whose cooperation may be

needed to achieve the vision.

- Motivating and

inspiring—helping people energize themselves

to overcome political, bureaucratic, and resource

barriers to change.

On a project, particularly a larger project, the project

manager is generally expected to be the project’s

leader as well. Leadership is not, however, limited to

the project manager: it may be demonstrated by many

different individuals at many different times during the

project. Leadership must be demonstrated at all levels of

the project (project leadership, technical leadership,

team leadership).

2.4.2. Communicating

Communicating involves the exchange of

information. The sender is responsible for making the

information clear, unambiguous, and complete so that the

receiver can receive it correctly. The receiver is

responsible for making sure that the information is

received in its entirety and understood correctly.

Communicating has many dimensions:

- Written and oral,

listening and speaking.

- Internal (within the

project) and external (to the customer, the

media, the public, etc.).

- Formal (reports,

briefings, etc.) and informal (memos, ad hoc

conversations, etc.).

- Vertical (up and down

the organization) and horizontal (with peers).

The general management

skill of communicating is related to, but not the same

as, Project Communications Management (described in

Chapter 10). Communicating is the broader subject and

involves a substantial body of knowledge that is not

unique to the project context, for example:

- Sender-receiver

models—feedback loops, barriers to

communications, etc.

- Choice of

media—when to communicate in writing, when

to communicate orally, when to write an informal

memo, when to write a formal report, etc.

- Writing

style—active vs. passive voice, sentence

structure, word choice, etc.

- Presentation

techniques—body language, design of visual

aids, etc.

- Meeting management

techniques—preparing an agenda, dealing with

conflict, etc.

Project Communications

Management is the application of these broad concepts to

the specific needs of a project; for example, deciding

how, when, in what form, and to whom to report project

performance.

2.4.3 Negotiating

Negotiating involves conferring with

others in order to come to terms or reach an agreement.

Agreements may be negotiated directly or with assistance;

mediation and arbitration are two types of assisted

negotiation. Negotiations occur around many issues, at

many times, and at many levels of the project. During the

course of a typical project, project staff are likely to

negotiate for any or all of the following:

- Scope, cost, and

schedule objectives.

- Changes to scope,

cost, or schedule.

- Contract terms and

conditions.

- Assignments.

- Resources.

2.4.4 Problem

Solving

Problem solving involves a combination of

problem definition and decision making. It is concerned

with problems that have already occurred (as opposed to

risk management that addresses potential problems).

Problem definition requires distinguishing between

causes and symptoms. Problems may be internal (a key

employee is reassigned to another project) or external (a

permit required to begin work is delayed). Problems may

be technical (differences of opinion about the best way

to design a product), managerial (a functional group is

not producing according to plan), or interpersonal

(personality or style clashes).

Decision making includes analyzing the problem to

identify viable solutions, and then making a choice from

among them. Decisions can be made or obtained (from the

customer, from the team, or from a functional manager).

Once made, decisions must be implemented. Decisions also

have a time element to them—the "right"

decision may not be the "best" decision if it

is made too early or too late.

2.4.5 Influencing the Organization

Influencing the organization done." It

requires aninvolves the ability to "get things

understanding of both the formal and informal structures

of all the organizations involved—the performing

organization, the customer, contractors, and numerous

others as appropriate. Influencing the organization also

requires an understanding of the mechanics of power and

politics.

Both power and politics are used here in their positive

senses. Pfeffer [5] defines power as "the potential

ability to influence behavior, to change the course of

events, to overcome resistance, and to get people to do

things that they would not otherwise do." In similar

fashion, Eccles [6] says that "politics is about

getting collective action from a group of people who may

have quite different interests. It is about being willing

to use conflict and disorder creatively. The negative

sense, of course, derives from the fact that attempts to

reconcile these interests result in power struggles and

organizational games that can sometimes take on a

thoroughly unproductive life of their own."

|

2.5

Socio-

economic

Iinfluences |

Like general

management, socioeconomic influences include a

wide range of topics and issues. The project management

team must understand that current conditions and trends

in this area may have a major effect on their project: a

small change here can translate, usually with a time lag,

into cataclysmic upheavals in the project itself. Of the

many potential socioeconomic influences, several major

categories that frequently affect projects are described

briefly below.

2.5.1 Standards and Regulations

The International Organization for

Standardization (ISO) differentiates between standards

and regulations as follows [7]:

- A standard is

a "document approved by a recognized body,

that provides, for common and repeated use,

rules, guidelines, or characteristics for

products, processes or services with which

compliance is not mandatory." There are

numerous standards in use covering everything

from thermal stability of hydraulic fluids to the

size of computer diskettes.

- A regulation is

a "document which lays down product, process

or service char-acteristics, including the

applicable administrative provisions, with which

com-pliance is mandatory." Building codes

are an example of regulations.

Care must be used in

discussing standards and regulations since there is a

vast gray area between the two, for example:

- Standards often begin

as guidelines that describe a preferred approach,

and later, with widespread adoption, become de

facto regulations (e.g., the use of the

Critical Path Method for scheduling major

construction projects).

- Compliance may be

mandated at different levels (e.g., by a

government agency, by the management of the

performing organization, or by the

projectmanagement team).

For many projects, standards and regulations (by whatever

definition) are well known and project plans can reflect

their effects. In other cases, the influence is unknown

or uncertain and must be considered under Project Risk

Management.

2.5.2 Internationalization

As more and more organizations engage in work

which spans national boundaries, more and more projects

span national boundaries as well. In addition to the

traditional concerns of scope, cost, time, and quality,

the project management team must also consider the effect

of time zone differences, national and regional holidays,

travel requirements for face-to-face meetings, the

logistics of teleconferencing, and often volatile

political differences.

2.5.3 Cultural Influences

Culture is the "totality of socially

transmitted behavior patterns, arts, beliefs,

institutions, and all other products of human work and

thought" [8]. Every project must operate within a

context of one or more cultural norms. This area of

influence includes political, economic, demographic,

educational, ethical, ethnic, religious, and other areas

of practice, belief, and attitudes that affect the way

people and organizations interact.

|