3

Project

Management

Processes |

Project management is an

integrative endeavor—an action, or failure to take

action, in one area will usually affect other areas. The

interactions may be straightforward and well-understood,

or they may be subtle and uncertain. For example, a scope

change will almost always affect project cost, but it may

or may not affect team morale or product quality.

These interactions often require trade-offs among project

objectives—performance in one area may be enhanced

only by sacrificing performance in another. Successful

project management requires actively managing these

interactions. To help in understanding the integrative

nature of project management, and to emphasize the

importance of integration, this document describes

project management in terms of its component processes

and their interactions. This chapter provides an

introduction to the concept of project management as a

number of interlinked processes and thus provides an

essential foundation for understanding the process

descriptions in Chapters 4 through 12. It includes the

following major sections:

3.1 Project Processes

3.2 Process Groups

3.3 Process Interactions

3.4 Customizing Process Interactions

|

3.2

Process

Groups |

Project management processes can be organized into five

groups of one or more processes each:

- Initiating

processes—recognizing that a project or

phase should begin and committing to do so.

- Planning

processes—devising and maintaining a

workable scheme to accomplish the business need

that the project was undertaken to address.

- Executing

processes—coordinating people and other

resources to carry out the plan.

- Controlling

processes—ensuring that project objectives

are met by monitoring and measuring progress and

taking corrective action when necessary.

- Closing

processes—formalizing acceptance of the

project or phase and bringing it to an orderly

end.

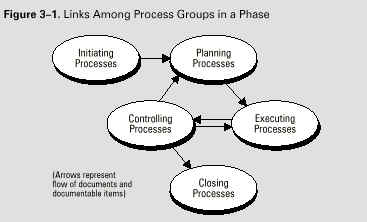

The process groups are

linked by the results they produce—the result or

outcome of one becomes an input to another. Among the

central process groups, the links are

iterated—planning provides executing with a

documented project plan early on, and then provides

documented updates to the plan as the project progresses.

These connections are illustrated in Figure 3–1.

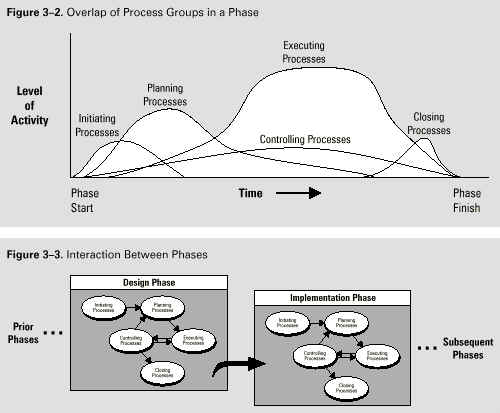

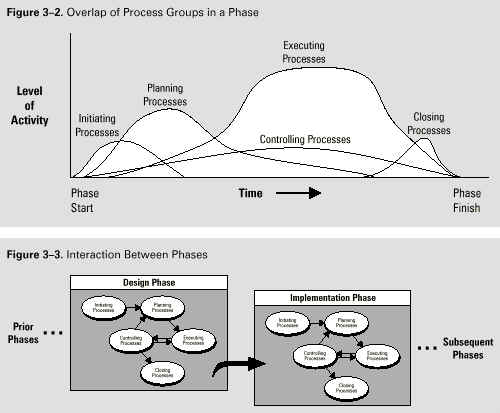

In addition, the project management process groups are

not discrete, one-time events; they are overlapping

activities which occur at varying levels of intensity

throughout each phase of the project. Figure 3–2 illustrates

how the process groups overlap and vary within a phase.

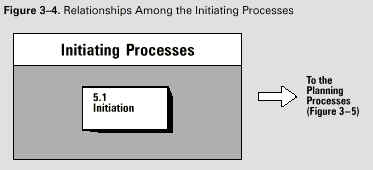

Finally, the process group interactions also cross phases

such that closing one phase provides an input to

initiating the next. For example, closing a design phase

requires customer acceptance of the design document.

Simultaneously, the design document defines the product

description for the ensuing implementation phase. This

interaction is illustrated in Figure 3–3.

Repeating the initiation processes at the start of each

phase helps to keep the project focused on the business

need it was undertaken to address. It should also help

ensure that the project is halted if the business need no

longer exists or if the project is unlikely to satisfy

that need. Business needs are discussed in more detail in

the introduction to Section 5.1, Initiation.

Although Figure

3–3 is drawn with discrete phases and discrete

processes, in an actual project there will be many

overlaps. The planning process, for example, must not

only provide details of the work to be done to bring the

current phase of the project to successful completion but

must also provide some preliminary description of work to

be done in later phases. This progressive detailing of

the project plan is often called rolling wave planning.

|

3.3

Process

Interactions |

Within each process

group, the individual processes are linked by their

inputs and outputs. By focusing on these links, we can

describe each process in terms of its:

- Inputs—documents

or documentable items that will be acted upon.

- Tools and

techniques—mechanisms applied to the inputs

to create the outputs.

- Outputs—documents

or documentable items that are a result of the

process.

The project management

processes common to most projects in most application

areas are listed here and described in detail in Chapters

4 through 12. The numbers in parentheses after the

process names identify the chapter and section where it

is described. The process interactions illustrated here

are also typical of most projects in most application

areas. Section 3.4 discusses customizing both process

descriptions and interactions.

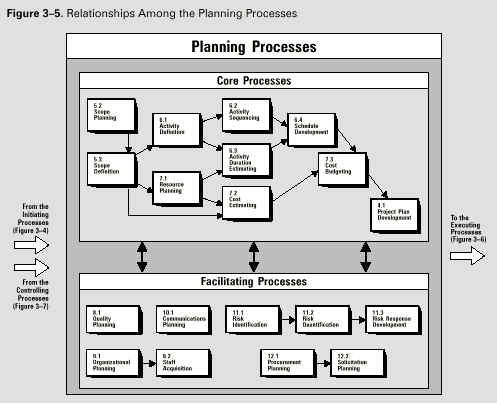

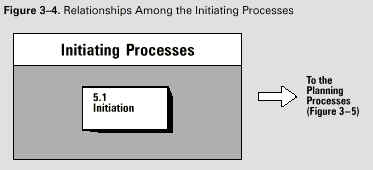

3.3.1 Initiating Processes

Figure 3–4 illustrates the single process in

this process group. Initiation (5.1)—committing the

organization to begin the next phase of the project.

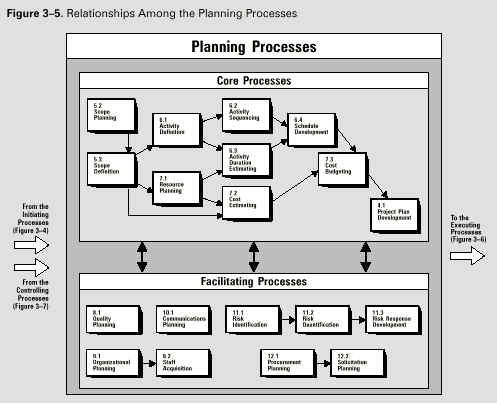

3.3.2 Planning Processes

Planning is of major importance to a project

because the project involves doing something which has

not been done before. As a result, there are relatively

more processes in this section. However, the number of

processes does not mean that project management is

primarily planning—the amount of planning performed

should be commensurate with the scope of the project and

the usefulness of the information developed.

The relationships among the project planning processes

are shown in Figure 3–5 (this chart is an

explosion of the ellipse labeled "planning

processes" in Figure 3–1). These

processes are subject to frequent iterations prior to

completing the plan. For example, if the initial

completion date is unacceptable, project resources, cost,

or even scope may need to be redefined. In addition,

planning is not an exact science—two different teams

could generate very different plans for the same project.

Core processes. Some planning processes have clear

dependencies that require them to be performed in

essentially the same order on most projects. For example,

activities must be defined before they can be scheduled

or costed. These core planning processes may be

iterated several times during any one phase of a project.

They include:

- Scope Planning

(5.2)—developing a written scope statement

as the basis for future project decisions.

- Scope Definition

(5.3)—subdividing the major project

deliverables into smaller, more manageable

components.

- Activity Definition

(6.1)—identifying the specific activities

that must be performed to produce the various

project deliverables.

- Activity Sequencing

(6.2)—identifying and documenting

interactivity dependencies.

- Activity Duration

Estimating (6.3)—estimating the number of

work periods which will be needed to complete

individual activities.

- Schedule Development

(6.4)—analyzing activity sequences, activity

durations, and resource requirements to create

the project schedule.

- Resource Planning

(7.1)—determining what resources (people,

equipment, materials) and what quantities of each

should be used to perform project activities.

- Cost Estimating

(7.2)—developing an approximation (estimate)

of the costs of the resources needed to complete

project activities.

- Cost Budgeting

(7.3)—allocating the overall cost estimate

to individual work items.

- Project Plan

Development (4.1)—taking the results of

other planning processes and putting them into a

consistent, coherent document.

Facilitating processes. Interactions among the

other planning processes are more dependent on the nature

of the project. For example, on some projects there may

be little or no identifiable risk until after most of the

planning has been done and the team recognizes that the

cost and schedule targets are extremely aggressive and

thus involve considerable risk. Although these facilitating

processes are performed intermittently and as needed

during project planning, they are not optional. They

include:

- Quality Planning

(8.1)—identifying which quality standards

are relevant to the project and determining how

to satisfy them.

- Organizational

Planning (9.1)—identifying, documenting, and

assigning project roles, responsibilities, and

reporting relationships.

- Staff Acquisition

(9.2)—getting the human resources needed

assigned to and working on the project.

- Communications

Planning (10.1)—determining the information

and communications needs of the stakeholders: who

needs what information, when will they need it,

and how will it be given to them.

- Risk Identification

(11.1)—determining which risks are likely to

affect the project and documenting the

characteristics of each.

- Risk Quantification

(11.2)—evaluating risks and risk

interactions to assess the range of possible

project outcomes.

- Risk Response

Development (11.3)—defining enhancement

steps for opportunities and responses to threats.

- Procurement Planning

(12.1)—determining what to procure and when.

- Solicitation Planning

(12.2)—documenting product requirements and

identifying potential sources.

3.3.3 Executing Processes

The executing processes include core processes

and facilitating processes as described in Section 3.3.2,

Planning Processes. Figure 3–6 illustrates

how the following processes interact:

- Project Plan

Execution (4.2)—carrying out the project

plan by performing the activities included

therein.

- Scope Verification

(5.4)—formalizing acceptance of the project

scope.

- Quality Assurance

(8.2)—evaluating overall project performance

on a regular basis to provide confidence that the

project will satisfy the relevant quality

standards.

- Team Development

(9.3)—developing individual and group skills

to enhance project performance.

- Information

Distribution (10.2)—making needed

information available to project stakeholders in

a timely manner.

- Solicitation

(12.3)—obtaining quotations, bids, offers,

or proposals as appropriate.

- Source Selection

(12.4)—choosing from among potential

sellers.

- Contract

Administration (12.5)—managing the

relationship with the seller.

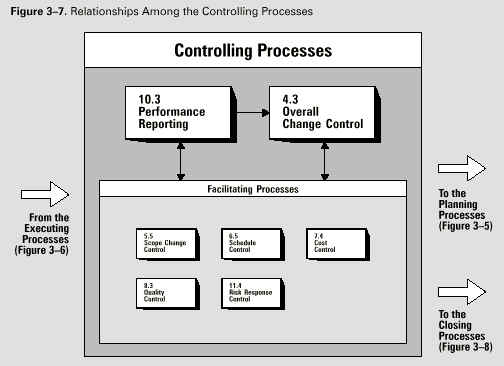

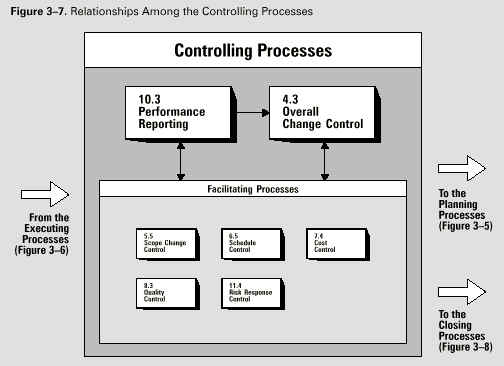

3.3.4 Controlling

Processes

Project performance must be measured regularly

to identify variances from the plan. Variances are fed

into the control processes in the various knowledge

areas. To the extent that significant variances are

observed (i.e., those that jeopardize the project

objectives), adjustments to the plan are made by

repeating the appropriate project planning processes. For

example, a missed activity finish date may require

adjustments to the current staffing plan, reliance on

overtime, or trade-offs between budget and schedule

objectives. Controlling also includes taking preventive

action in anticipation of possible problems.

The controlling process

group contains core processes and facilitating processes

as described in Section 3.3.2, Planning Processes. Figure

3–7 illustrates how the following processes

interact:

- Overall Change

Control (4.3)—coordinating changes across

the entire project.

- Scope Change Control

(5.5)—controlling changes to project scope.

- Schedule Control

(6.5)—controlling changes to the project

schedule.

- Cost Control

(7.4)—controlling changes to the project

budget.

- Quality Control

(8.3)—monitoring specific project results to

determine if they comply with relevant quality

standards and identifying ways to eliminate

causes of unsatisfactory performance.

- Performance Reporting

(10.3)—collecting and disseminating

performance information. This includes status

reporting, progress measurement, and forecasting.

- Risk Response Control

(11.4)—responding to changes in risk over

the course of the project.

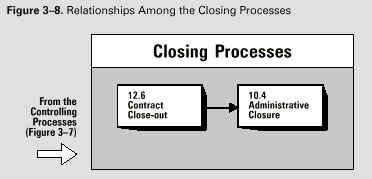

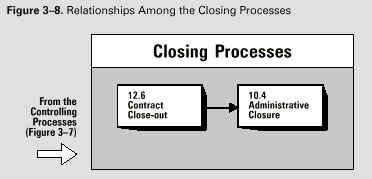

3.3.5 Closing

Processes

Figure 3–8 illustrates how the

following processes interact:

- Administrative

Closure (10.4)—generating, gathering, and

disseminating information to formalize phase or

project completion.

- Contract Close-out

(12.6)—completion and settlement of the

contract, including resolution of any open items.

|

3.4

Customizing

Process

Interactions

|

The processes identified and the interactions

illustrated in Section 3.3 meet the test of general

acceptance—they apply to most projects most of the

time. However, not all of the processes will be needed on

all projects, and not all of the interactions will apply

to all projects. For example:

- An organization that

makes extensive use of contractors may explicitly

describe where in the planning process each

procurement process occurs.

- The absence of a

process does not mean that it should not be

performed. The project management team should

identify and manage all the processes that are

needed to ensure a successful project.

- Projects which are

dependent on unique resources (commercial

software de-velopment, biopharmaceuticals, etc.)

may define roles and responsibilities priorto

scope definition since what can be done may be a

function of who will beavailable to do it.

- Some process outputs

may be predefined as constraints. For example,

managementmay specify a target completion date

rather than allowing it to be determined by the

planning process.

- Larger projects may

need relatively more detail. For example, risk

identification might be further subdivided to

focus separately on identifying cost risks,

schedule risks, technical risks, and quality

risks.

- On subprojects and

smaller projects, relatively little effort will

be spent on processes whose outputs have been

defined at the project level (e.g., a

subcontractor may ignore risks explicitly assumed

by the prime contractor) or on processes that

provide only marginal utility (there may be no

formal communicationsplan on a four-person

project).

When there is a need to

make a change, the change should be clearly identified,

carefully evaluated, and actively managed.

|