7

Project

Cost

Management |

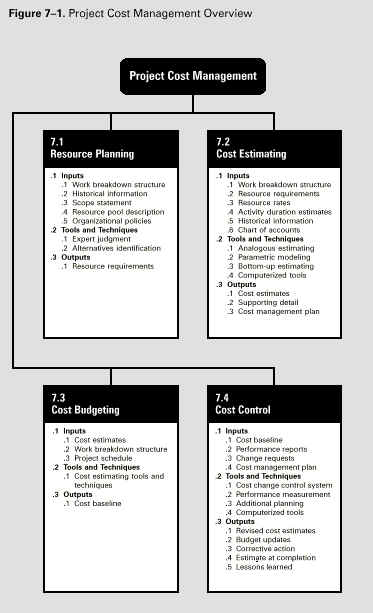

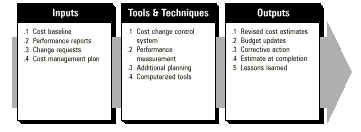

Project Cost Management includes

the processes required to ensure that the project is

completed within the approved budget. Figure 7–1 provides

an overview of the following major processes:

7.1 Resource Planning—determining

what resources (people, equipment, materials) and what

quantities of each should be used to perform project

activities.

7.2 Cost Estimating—developing an

approximation (estimate) of the costs of the resources

needed to complete project activities.

7.3 Cost Budgeting—allocating

the overall cost estimate to individual work items.

7.4 Cost Control—controlling

changes to the project budget.

These processes interact with each other and with the

processes in the other knowledge areas as well. Each

process may involve effort from one or more individuals

or groups of individuals based on the needs of the

project. Each process generally occurs at least once in

every project phase.

Although the processes are presented here as discrete

elements with well-defined interfaces, in practice they

may overlap and interact in ways not detailed here.

Process interactions are discussed in detail in Chapter

3. Project cost management is primarily concerned with

the cost of the resources needed to complete project

activities. However, project cost management should also

consider the effect of project decisions on the cost of

using the project product.

For example, limiting the number of design reviews may

reduce the cost of the project at the expense of an

increase in the customer’s operating costs. This

broader view of project cost management is often called life-cycle

costing. In many application areas predicting and

analyzing the prospective financial performance of the

project product is done outside the project. In others

(e.g., capital facilities projects), project cost

management also includes this work. When such predictions

and analysis are included, project cost management will

include additional processes and numerous general

management techniques such as return on investment,

discounted cash flow, payback analysis, and others.

Project cost management should consider the information

needs of the project stakeholders—different

stakeholders may measure project costs in different ways

and at different times. For example, the cost of a

procurement item may be measured when committed, ordered,

delivered, incurred, or recorded for accounting purposes.

When project costs are used as a component of a reward

and recognition system (reward and recognition systems

are discussed in Section 9.3.2.3), controllable and

uncontrollable costs should be estimated and budgeted

separately to ensure that rewards reflect actual

performance.

On some projects,

especially smaller ones, resource planning, cost

estimating, and cost budgeting are so tightly linked that

they are viewed as a single process (e.g., they may be

performed by a single individual over a relatively short

period of time). They are presented here as distinct

processes because the tools and techniques for each are

different.

|

7.1

Resource

Planning |

Resource planning

involves determining what physical resources (people,

equipment, materials) and what quantities of each should

be used to perform project activities. It must be closely

coordinated with cost estimating (described in Section

7.2). For example:

- A construction

project team will need to be familiar with local

building codes. Such knowledge is often readily

available at virtually no cost by using local

labor. However, if the local labor pool lacks

experience with unusual or specialized

construction techniques, the additional cost for

a consultant might be the most effective way to

secure knowledge of the local building codes.

- An automotive design

team should be familiar with the latest in

automated assembly techniques. The requisite

knowledge might be obtained by hiring a

consultant, by sending a designer to a seminar on

robotics, or by including someone from

manufacturing as a member of the team.

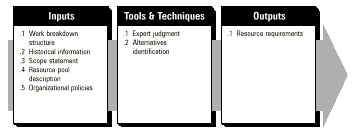

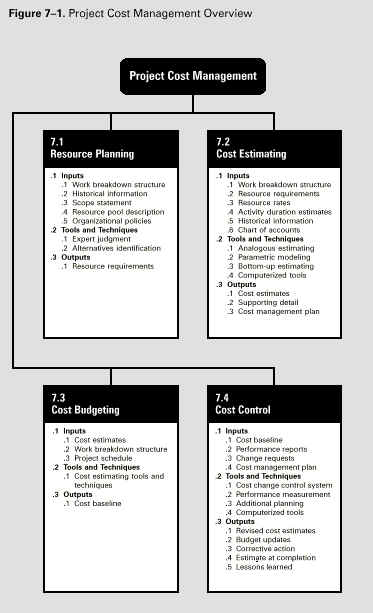

7.1.1 Inputs to

Resource Planning

.1 Work breakdown structure.

The work breakdown structure (WBS, described in

Section 5.3.3.1) identifies the project elements that

will need resources and thus is the primary input to

resource planning. Any relevant outputs from other

planning processes should be provided through the WBS to

ensure proper control.

.2 Historical information. Historical

information regarding what types of resources were

required for similar work on previous projects should be

used if available.

.3 Scope statement. The

scope statement (described in Section 5.2.3.1) contains

the project justification and the project objectives,

both of which should be considered explicitly during

resource planning.

.4 Resource pool description. Knowledge

of what resources (people, equipment, material) are

potentially available is necessary for resource planning.

The amount of detail and the level of specificity of the

resource pool description will vary. For example, during

the early phases of an engineering design project, the

pool may include "junior and senior engineers"

in large numbers. During later phases of the same

project, however, the pool may be limited to those

individuals who are knowledgeable about the project as a

result of having worked on the earlier phases.

.5 Organizational policies. The

policies of the performing organization regarding

staffing and the rental or purchase of supplies and

equipment must be considered during resource planning.

7.1.2

Tools and Techniques for Resource Planning

.1 Expert judgment. Expert

judgment will often be required to assess the inputs to

this process. Such expertise may be provided by any group

or individual with specialized knowledge or training and

is available from many sources including:

- Other

units within the performing organization.

- Consultants.

- Professional

and technical associations.

- Industry

groups.

.2

Alternatives identification. Alternatives

identification is discussed in Section 5.2.2.3.

7.1.3 Outputs from Resource Planning

.1 Resource requirements. The

output of the resource planning process is a description

of what types of resources are required and in what

quantities for each element of the work breakdown

structure. These resources will be obtained either

through staff acquisition (described in Section 9.2) or

procurement (described in Chapter 12).

|

7.2

Cost

Estimating |

Cost

estimating involves developing an approximation

(estimate) of the costs of the resources needed to

complete project activities. When a project is performed

under contract, care should be taken to distinguish cost

estimating from pricing. Cost estimating involves

developing an assessment of the likely quantitative

result—how much will it cost the performing

organization to provide the product or service involved.

Pricing is a business decision—how much will the

performing organization charge for the product or

service—that uses the cost estimate as but one

consideration of many.

Cost estimating includes identifying and considering

various costing alternatives. For example, in most

application areas, additional work during a design phase

is widely held to have the potential for reducing the

cost of the production phase. The cost estimating process

must consider whether the cost of the additional design

work will offset the expected savings.

Inputs

Tools & Techniques Outputs

7.2.1 Inputs to

Cost Estimating

.1 Work breakdown structure. The

WBS is described in Section 5.3.3.1. It will be used to

organize the cost estimates and to ensure that all

identified work has been estimated.

.2 Resource requirements. Resource

requirements are described in Section 7.1.3.1.

.3 Resource rates. The

individual or group preparing the estimates must know the

unit rates (e.g., staff cost per hour, bulk material cost

per cubic yard) for each resource in order to calculate

project costs. If actual rates are not known, the rates

themselves may have to be estimated.

.4 Activity duration estimates.

Activity duration estimates (described in Section

6.3) will affect cost estimates on any project where the

project budget includes an allowance for the cost of

financing (i.e., interest charges).

.5 Historical information. Information

on the cost of many categories of resources is often

available from one or more of the following sources:

- Project

files—one or more of the organizations

involved in the project may maintain records of

previous project results that are detailed enough

to aid in developing cost estimates. In some

application areas, individual team members may

maintain such records.

- Commercial cost

estimating databases—historical information

is often available commercially.

- Project team

knowledge—the individual members of the

project team may remember previous actuals or

estimates. While such recollections may be

useful, they are generally far less reliable than

documented results.

.6 Chart of accounts.

A chart of accounts describes the coding

structure used by the performing organization to report

financial information in its general ledger. Project cost

estimates must be assigned to the correct accounting

category.

7.2.2 Tools and Techniques for Cost Estimating

.1 Analogous estimating. Analogous

estimating, also called top-down estimating, means

using the actual cost of a previous, similar project as

the basis for estimating the cost of the current project.

It is frequently used to estimate total project costs

when there is a limited amount of detailed information

about the project (e.g., in the early phases). Analogous

estimating is a form of expert judgment (described in

Section 7.1.2.1).

Analogous estimating is generally less costly than other

techniques, but it is also generally less accurate. It is

most reliable when (a) the previous projects are similar

in fact and not just in appearance, and (b) the

individuals or groups preparing the estimates have the

needed expertise.

.2 Parametric modeling. Parametric

modeling involves using project characteristics

(parameters) in a mathematical model to predict project

costs. Models may be simple (residential home

construction will cost a certain amount per square foot

of living space) or complex (one model of software

development costs uses 13 separate adjustment factors

each of which has 5–7 points on it).

Both the cost and accuracy of parametric models varies

widely. They are most likely to be reliable when (a) the

historical information used to develop the model was

accurate, (b) the parameters used in the model are

readily quantifiable, and (c) the model is scalable

(i.e., it works as well for a very large project as for a

very small one).

.3 Bottom-up estimating. This

technique involves estimating the cost of individual work

items, then summarizing or rolling-up the individual

estimates to get a project total. The cost and accuracy

of bottom-up estimating is driven by the size of the

individual work items: smaller work items increase both

cost and accuracy. The project management team must weigh

the additional accuracy against the additional cost.

.4 Computerized tools. Computerized

tools such as project management software and

spreadsheets are widely used to assist with cost

estimating. Such products can simplify the use of the

tools described above and thereby facilitate rapid

consideration of many costing alternatives.

7.2.3 Outputs from Cost Estimating

.1 Cost estimates. Cost

estimates are quantitative assessments of the likely

costs of the resources required to complete project

activities. They may be presented in summary or in

detail. Costs must be estimated for all resources that

will be charged to the project. This includes, but is not

limited to, labor, materials, supplies, and special

categories such as an inflation allowance or cost

reserve.

Cost estimates are generally expressed in units of

currency (dollars, francs, yen, etc.) in order to

facilitate comparisons both within and across projects.

Other units such as staff hours or staff days may be

used, unless doing so will misstate project costs (e.g.,

by failing to differentiate among resources with very

different costs). In some cases, estimates will have to

be provided using multiple units of measure in order to

facilitate appropriate management control.

Cost estimates may benefit from being refined during the

course of the project to reflect the additional detail

available. In some application areas, there are

guidelines for when such refinements should be made and

what degree of accuracy is expected. For example, AACE

International has identified a progression of five types

of estimates of construction costs during engineering:

order of magnitude, conceptual, preliminary, definitive,

and control.

.2 Supporting detail. Supporting

detail for the cost estimates should include:

- A description of the

scope of work estimated. This is often provided

by a reference to the WBS.

- Documentation of the

basis for the estimate, i.e., how it was

developed.

- Documentation of any

assumptions made.

- An indication of the

range of possible results, for example, $10,000

± $1,000 to indicate that the item is expected

to cost between $9,000 and $11,000.

The amount and type of

additional detail varies by application area. Retaining

even rough notes may prove valuable by providing a better

understanding of how the estimate was developed.

.3 Cost management plan. The cost

management plan describes how cost variances will be

managed (e.g., different responses to major problems than

to minor ones). A cost management plan may be formal or

informal, highly detailed or broadly framed based on the

needs of the project stakeholders. It is a subsidiary

element of the overall project plan (discussed in Section

4.1.3.1).

|

7.4

Cost

Control |

Cost control is concerned with (a) influencing the

factors which create changes to the cost baseline to

ensure that changes are beneficial, (b) determining that

the cost baseline has changed, and (c) managing the

actual changes when and as they occur. Cost control

includes:

- Monitoring cost

performance to detect variances from plan.

- Ensuring that all

appropriate changes are recorded accurately in

the cost baseline.

- Preventing incorrect,

inappropriate, or unauthorized changes from being

included in the cost baseline.

- Informing appropriate

stakeholders of authorized changes.

Cost control includes searching out the "whys"

of both positive and negative variances. It must be

thoroughly integrated with the other control processes

(scope change control, schedule control, quality control,

and others as discussed in Section 4.3). For example,

inappropriate responses to cost variances can cause

quality or schedule problems or produce an unacceptable

level of risk later in the project.

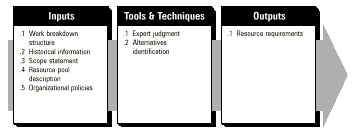

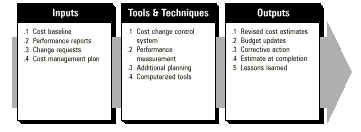

7.4.1 Inputs to

Cost Control

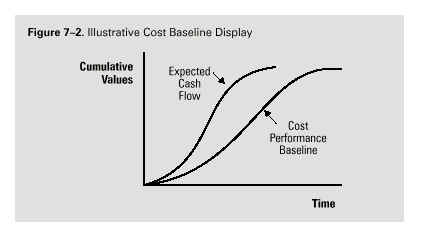

.1 Cost baseline. The cost

baseline is described in Section 7.3.3.1.

.2 Performance reports. Performance

reports (discussed in Section 10.3.3.1) provide

information on cost performance such as which budgets

have been met and which have not. Performance reports may

also alert the project team to issues which may cause

problems in the future.

.3 Change requests. Change

requests may occur in many forms—oral or written,

direct or indirect, externally or internally initiated,

and legally mandated or optional. Changes may require

increasing the budget or may allow decreasing it.

.4 Cost management plan. The

cost management plan is described in Section 7.2.3.3.

7.4.2 Tools and Techniques for Cost Control

.1 Cost change control system.

A cost change control system defines the

procedures by which the cost baseline may be changed. It

includes the paperwork, tracking systems, and approval

levels necessary for authorizing changes. The cost change

control system should be integrated with the overall

change control system discussed in Section 4.3.

.2 Performance measurement. Performance

measurement techniques, described in Section 10.3.2, help

to assess the magnitude of any variations which do occur.

Earned value analysis, described in Section 10.3.2.4, is

especially useful for cost control. An important part of

cost control is to determine what is causing the variance

and to decide if the variance requires corrective action.

.3 Additional planning. Few projects run exactly

according to plan. Prospective changes may require new or

revised cost estimates or analysis of alternative

approaches.

.4 Computerized tools. Computerized

tools such as project management software and

spreadsheets are often used to track planned costs vs.

actual costs, and to forecast the effects of cost

changes.

7.4.3 Outputs from Cost Control.

.1 Revised cost estimates. Revised

cost estimates are modifications to the cost information

used to manage the project. Appropriate stakeholders must

be notified as needed. Revised cost estimates may or may

not require adjustments to other aspects of the overall

project plan.

.2 Budget updates. Budget

updates are a special category of revised cost estimates.

Budget updates are changes to an approved cost baseline.

These numbers are generally revised only in response to

scope changes. In some cases, cost variances may be so

severe that "rebaselining" is needed in order

to provide a realistic measure of performance.

.3 Corrective action. Corrective

action is anything done to bring expected future project

performance into line with the project plan.

.4 Estimate at completion. An

estimate at completion (EAC) is a forecast of total

project costs based on project performance. The most

common forecasting techniques are some variation of:

- EAC = Actuals to date

plus the remaining project budget modified by a

performance factor, often the cost performance

index described in Section 10.3.2.4. This

approach is most often used when current

variances are seen as typical of future

variances.

- EAC = Actuals to date

plus a new estimate for all remaining work. This

approach is most often used when past performance

shows that the original estimating assumptions

were fundamentally flawed, or that they are no

longer relevant due to a change in conditions.

- EAC = Actuals to date

plus remaining budget. This approach is most

often used when current variances are seen as

atypical and the project management team’s

expectation is that similar variances will not

occur in the future. Each of the above approaches

may be the correct approach for any given work

item.

.5 Lessons learned. The

causes of variances, the reasoning behind the corrective

action chosen, and other types of lessons learned from

cost control should be documented so that they become

part of the historical database for both this project and

other projects of the performing organization.

|