8

Project

Quality

Management

|

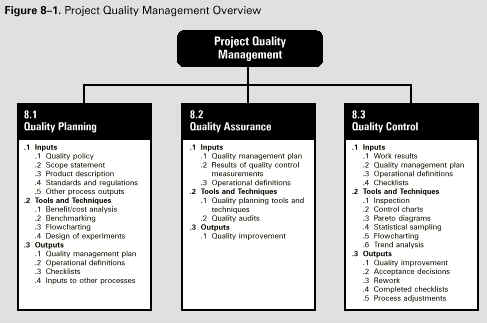

Project Quality Management includes

the processes required to ensure that the project will

satisfy the needs for which it was undertaken. It

includes "all activities of the overall management

function that determine the quality policy, objectives,

and responsibilities and implements them by means such as

quality planning, quality control, quality assurance, and

quality improvement, within the quality system" [1].

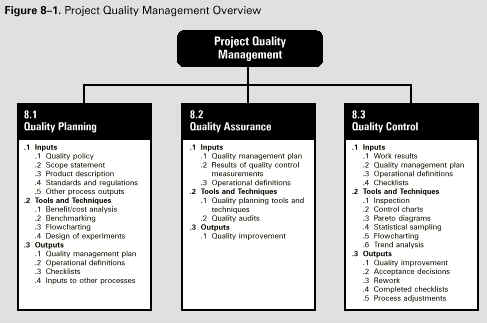

Figure 8–1 provides an overview of the

following major project quality management processes:

8.1 Quality Planning—identifying

which quality standards are relevant to the project and

determining how to satisfy them.

8.2 Quality Assurance—evaluating

overall project performance on a regular basis to provide

confidence that the project will satisfy the relevant

quality standards.

8.3 Quality Control—monitoring

specific project results to determine if they comply with

relevant quality standards and identifying ways to

eliminate causes of unsatisfactory performance.

These processes interact with each other and with the

processes in the other knowledge areas as well. Each

process may involve effort from one or more individuals

or groups of individuals based on the needs of the

project. Each process generally occurs at least once in

every project phase. Although the processes are presented

here as discrete elements with well-defined interfaces,

in practice they may overlap and interact in ways not

detailed here. Process interactions are discussed in

detail in Chapter 3, Project Management Processes.

The basic approach to quality management described in

this section is intended to be compatible with that of

the International Organization for Standardization (ISO)

as detailed in the ISO 9000 and 10000 series of standards

and guidelines. This generalized approach should also be

compatible with (a) proprietary ap-proaches to quality

management such as those recommended by Deming, Juran,

Crosby, and others, and (b) non-proprietary approaches

such as Total Quality Management (TQM), Continuous

Improvement, and others. Project quality management must

address both the management of the project and the

product of the project. Failure to meet quality

requirements in either dimension can have serious

negative consequences for any or all of the project

stake-holders. For example:

- Meeting

customer requirements by overworking the project

team may produce negative consequences in the

form of increased employee turnover.

- Meeting

project schedule objectives by rushing planned

quality inspections may produce negative

consequences when errors go undetected.

Quality is "the

totality of characteristics of an entity that bear on its

ability to satisfy stated or implied needs" [2]. A

critical aspect of quality management in the project

context is the necessity to turn implied needs into

stated needs through project scope management, which is

described in Chapter 5.

The project management team must be careful not to

confuse quality with grade. Grade is

"a category or rank given to entities having the

same functional use but different requirements for

quality" [3]. Low quality is always a problem; low

grade may not be. For example, a software product may be

of high quality (no obvious bugs, readable manual) and

low grade (a limited number of features), or of low

quality (many bugs, poorly organized user documentation)

and high grade (numerous features).

Determining and delivering the required levels of both

quality and grade are the responsibilities of the project

manager and the project management team. The project

management team should also be aware that modern quality

management complements modern project management. For

example, both disciplines recognize the importance of:

- Customer

satisfaction—understanding, managing, and

influencing needs so that customer expectations

are met or exceeded. This requires a combination

of conformance to specifications (the

project must produce what it said it would

produce) and fitness for use (the product

or service produced must satisfy real needs).

- Prevention over

inspection—the cost of avoiding mistakes is

always much less than the cost of correcting

them.

- Management

responsibility—success requires the participation

of all members of the team, but it remains

the responsibility of management to

provide the resources needed to succeed.

- Processes within

phases—the repeated plan-do-check-act cycle

described by Deming and others is highly similar

to the combination of phases and processes

discussed in Chapter 3, Project Management

Processes.

In addition, quality

improvement initiatives undertaken by the performing

organization (e.g., TQM, Continuous Improvement, and

others) can improve the quality of the project management

as well as the quality of the project product. However,

there is an important difference that the project

management team must be acutely aware of—the

temporary nature of the project means that investments in

product quality improvement, especially defect prevention

and appraisal, must often be borne by the performing

organization since the project may not last long enough

to reap the rewards.

|

8.1

Quality

Planning

|

Quality planning involves identifying which quality

standards are relevant to the project and determining how

to satisfy them. It is one of the key facilitating

processes during project planning (see Section 3.3.2,

Planning Processes) and should be performed regularly and

in parallel with the other project planning processes.

For example, the desired management quality may require

cost or schedule adjustments, or the desired product

quality may require a detailed risk analysis of an

identified problem. Prior to development of the ISO 9000

Series, the activities described here as quality

planning were widely discussed as part of quality

assurance.

The quality planning techniques discussed here are those

used most frequently on projects. There are many others

that may be useful on certain projects or in some

application areas. The project team should also be aware

of one of the fundamental tenets of modern quality

management—quality is planned in, not inspected in.

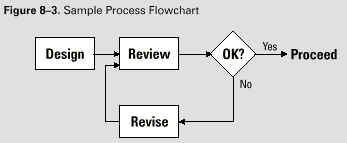

8.1.1 Inputs to

Quality Planning

.1 Quality policy. Quality

policy is "the overall intentions and direction of

an organization with regard to quality, as formally

expressed by top management" [4]. The quality policy

of the performing organization can often be adopted

"as is" for use by the project. However, if the

performing organization lacks a formal quality policy, or

if the project involves multiple performing organizations

(as with a joint venture), the project management team

will need to develop a quality policy for the project.

Regardless of the origin of the quality policy, the

project management team is responsible for ensuring that

the project stakeholders are fully aware of it (e.g.,

through appropriate information distribution, as

described in Section 10.2).

.2 Scope

statement. The scope statement

(described in Section 5.2.3.1) is a key input to quality

planning since it documents major project deliverables as

well as the project objectives which serve to define

important stakeholder requirements.

.3 Product description. Although

elements of the product description (described in Section

5.1.1.1) may be embodied in the scope statement, the

product description will often contain details of

technical issues and other concerns that may affect

quality planning.

.4 Standards and regulations. The

project management team must consider any

ap-plication-area-specific standards or regulations that

may affect the project. Section 2.5.1 discusses standards

and regulations.

.5 Other process outputs. In

addition to the scope statement and product description,

processes in other knowledge areas may produce outputs

that should be considered as part of quality planning.

For example, procurement planning (described in Section

12.1) may identify contractor quality requirements that

should be reflected in the overall quality management

plan.

8.1.2 Tools and Techniques for Quality Planning

.1 Benefit/cost analysis.

The quality planning process must consider

benefit/cost trade-offs, as described in Section 5.2.2.2.

The primary benefit of meeting quality requirements is

less rework, which means higher productivity, lower

costs, and increased stakeholder satisfaction. The

primary cost of meeting quality requirements is the

expense associated with project quality management

activities. It is axiomatic of the quality management

discipline that the benefits outweigh the costs.

.2 Benchmarking. Benchmarking

involves comparing actual or planned project practices to

those of other projects in order to generate ideas for

improvement and to provide a standard by which to measure

performance. The other projects may be within the

performing organization or outside of it, and may be

within the same application area or in another.

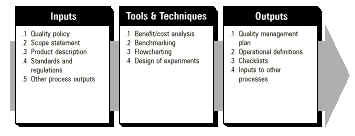

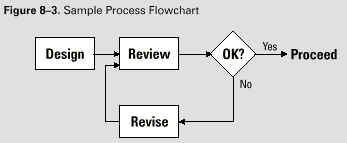

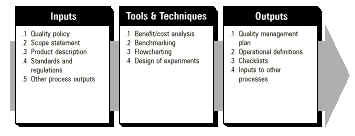

.3 Flowcharting. A flowchart is any

diagram which shows how various elements of a system

relate. Flowcharting techniques commonly used in quality

management include:

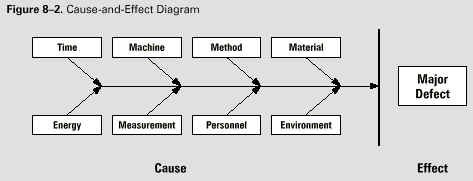

- Cause-and-effect

diagrams, also called Ishikawa diagrams or

fishbone diagrams, which illustrate how

various causes and subcauses relate to create

potential problems or effects. Figure 8–2

is an example of a generic cause-and-effect

diagram.

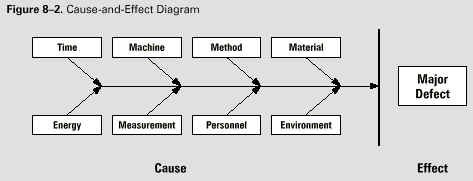

- System or process

flowcharts, which show how various elements

of a system interrelate.

Figure 8–3 is

an example of a process flowchart for design reviews.

Flowcharting can help the project team anticipate what

and where quality problems might occur and thus can help

to develop approaches to dealing with them.

.4 Design of experiments. Design

of experiments is an analytical technique which helps

identify which variables have the most influence on the

overall outcome. The technique is applied most frequently

to product of the project issues (e.g., automotive

designers might wish to determine which combination of

suspension and tires will produce the most desirable ride

characteristics at a reasonable cost).

However, it can also be applied to project management

issues such as cost and schedule trade-offs. For example,

senior engineers will cost more than junior engineers,

but can also be expected to complete the assigned work in

less time. An appropriately designed

"experiment" (in this case, computing project

costs and durations for various combinations of senior

and junior engineers) will often allow determination of

an optimal solution from a relatively limited number of

cases.

8.1.3 Outputs from Quality Planning

.1 Quality management plan.

The quality management plan should describe how

the project management team will implement its quality

policy. In ISO 9000 terminology, it should describe the project

quality system: "the organizational structure,

responsibilities, procedures, processes, and resources

needed to implement quality management" [5].

The quality management plan provides input to the overall

project plan (described in Section 4.1, Project Plan

Development) and must address quality control, quality

assurance, and quality improvement for the project. The

quality management plan may be formal or informal, highly

detailed, or broadly framed, based on the needs of the

project.

.2 Operational definitions. An

operational definition describes, in very specific terms,

what something is, and how it is measured by the quality

control process. For example, it is not enough to say

that meeting the planned schedule dates is a measure of

management quality; the project management team must also

indicate whether everyactivity must start on time, or

only finish on time; whether individual activities will

be measured or only certain deliverables, and if so,

which ones. Operational definitions are also called metrics

in some application areas.

.3 Checklists. A checklist is a

structured tool, usually industry- or activity-specific,

used to verify that a set of required steps has been

performed. Checklists may be simple or complex. They are

usually phrased as imperatives ("Do this!") or

interrogatories ("Have you done this?"). Many

organizations have standardized checklists available to

ensure consistency in frequently performed activities. In

some application areas, checklists are also available

from professional associations or commercial service

providers.

.4 Inputs to other processes. The

quality planning process may identify a need for further

activity in another area.

|

8.2

Quality

Assurance |

Quality assurance is all the planned and systematic

activities implemented within the quality system to

provide confidence that the project will satisfy the

relevant quality standards [6]. It should be performed

throughout the project. Prior to development of the ISO

9000 Series, the activities described under quality

planning were widely included as part of quality

assurance.

Quality assurance is often provided by a Quality

Assurance Department or similarly titled organizational

unit, but it does not have to be. Assurance may be

provided to the project management team and to the

management of the performing organization (internal

quality assurance) or it may be provided to the customer

and others not actively involved in the work of the

project (external quality assurance).

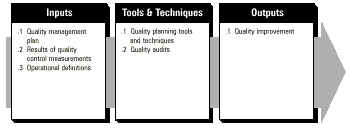

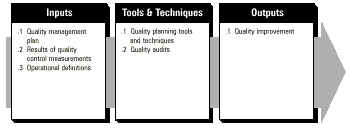

8.2.1 Inputs to

Quality Assurance

.1 Quality management plan.

The quality management plan is described in

Section 8.1.3.1.

.2 Results of quality control

measurements. Quality control

measurements are records of quality control testing and

measurement in a format for comparison and analysis.

.3 Operational definitions. Operational

definitions are described in Section 8.1.3.2.

8.2.2 Tools and Techniques for Quality

Assurance

.1 Quality planning tools and

techniques. The quality planning tools

and techniques described in Section 8.1.2 can be used for

quality assurance as well.

.2 Quality audits. A quality audit

is a structured review of other quality management

activities. The objective of a quality audit is to

identify lessons learned that can improve performance of

this project or of other projects within the performing

organization. Quality audits may be scheduled or random,

and they may be carried out by properly trained in-house

auditors or by third parties such as quality system

registration agencies.

8.2.3 Outputs from Quality Assurance

.1 Quality improvement.

Quality improvement includes taking action to

increase the effectiveness and efficiency of the project

to provide added benefits to the project stakeholders. In

most cases, implementing quality improvements will

require preparation of change requests or taking of

corrective action and will be handled according to

procedures for overall change control, as described in

Section 4.3.

|

8.3

Quality

Control |

Quality control

involves monitoring specific project results to determine

if they comply with relevant quality standards and

identifying ways to eliminate causes of un-satisfactory

results. It should be performed throughout the project.

Project results include both product results such

as deliverables and management results such as

cost and schedule performance. Quality control is often

performed by a Quality Control Department or similarly

titled organizational unit, but it does not have to be.

The project management team should have a working

knowledge of statistical quality control, especially

sampling and probability, to help them evaluate quality

control outputs. Among other subjects, they should know

the differences between:

- Prevention (keeping

errors out of the process) and inspection

(keeping errors out of the hands of the

customer).

- Attribute sampling

(the result conforms or it does not) and

variables sampling (the result is rated on a

continuous scale that measures the degree of

conformity).

- Special causes

(unusual events) and random causes (normal

process variation).

- Tolerances (the

result is acceptable if it falls within the range

specified by the tolerance) and control limits

(the process is in control if the result falls

within the control limits).

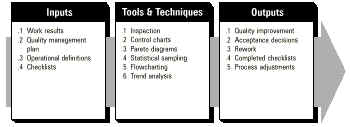

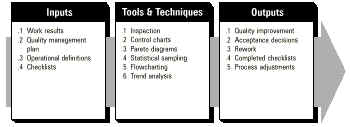

8.3.1 Inputs to

Quality Control

.1 Work results. Work

results (described in Section 4.2.3.1) include both process

results and product results. Information about

the planned or expected results (from the project plan)

should be available along with information about the

actual results.

.2 Quality management plan. The

quality management plan is described in Section 8.1.3.1.

.3 Operational definitions. Operational

definitions are described in Section 8.1.3.2.

.4 Checklists. Checklists

are described in Section 8.1.3.3.

8.3.2 Tools and

Techniques for Quality Control

.1 Inspection. Inspection

includes activities such as measuring, examining, and

testing undertaken to determine whether results conform

to requirements. Inspections may be conducted at any

level (e.g., the results of a single activity may be

inspected or the final product of the project may be

inspected). Inspections are variously called reviews,

product reviews, audits, and walk-throughs; in some

application areas, these terms have narrow and specific

meanings.

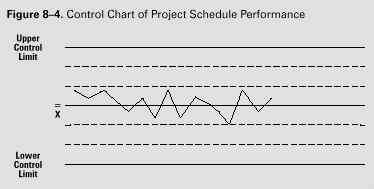

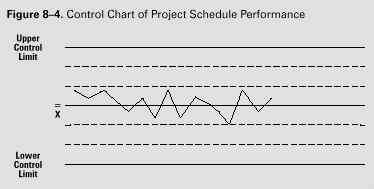

.2 Control charts. Control charts

are a graphic display of the results, over time, of a

process. They are used to determine if the process is

"in control" (e.g., are differences in the

results created by random variations or are unusual

events occurring whose causes must be identified and

corrected?). When a process is in control, the process

should not be adjusted. The process may be changed in

order to provide improvements but it should not be

adjusted when it is in control.

Control charts may be used to monitor any type of output

variable. Although used most frequently to track

repetitive activities such as manufactured lots, control

charts can also be used to monitor cost and schedule

variances, volume and frequency of scope changes, errors

in project documents, or other management results to help

determine if the "project management process"

is in control. Figure 8–4 is a control chart

of project schedule performance.

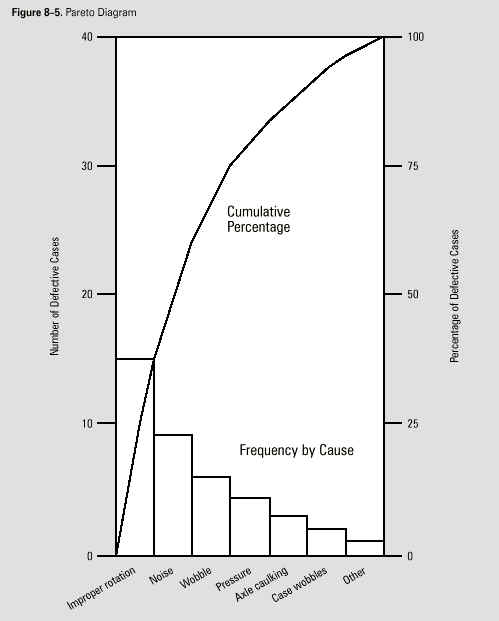

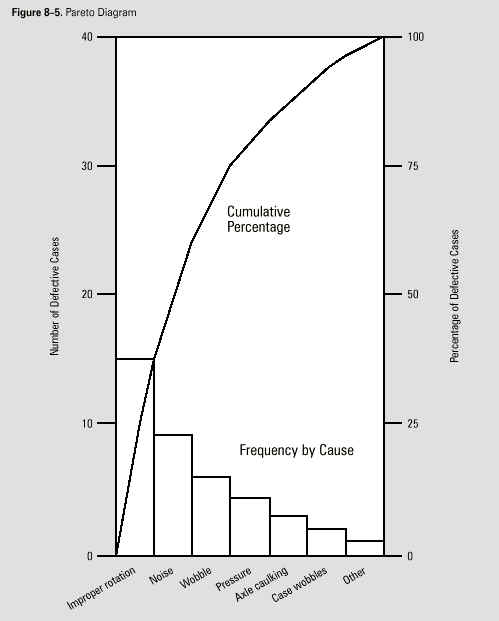

.3 Pareto diagrams. A

Pareto diagram is a histogram, ordered by frequency of

occurrence, that shows how many results were generated by

type or category of identified cause (see Figure

8–5). Rank ordering is used to guide corrective

action—the project team should take action to fix

the problems that are causing the greatest number of

defects first. Pareto diagrams are conceptually related

to Pareto’s Law, which holds that a relatively small

number of causes will typically produce a large majority

of the problems or defects.

.4 Statistical sampling. Statistical

sampling involves choosing part of a population of

interest for inspection (e.g., selecting ten engineering

drawings at random from a list of 75). Appropriate

sampling can often reduce the cost of quality control.

There is a substantial body of knowledge on statistical

sampling; in some application areas, it is necessary for

the project management team to be familiar with a variety

of sampling techniques.

.5 Flowcharting. Flowcharting

is described in Section 8.1.2.3. Flowcharting is used in

quality control to help analyze how problems occur.

.6 Trend analysis. Trend

analysis involves using mathematical techniques to

forecast future outcomes based on historical results.

Trend analysis is often used to monitor:

- Technical

performance—how many errors or defects have

been identified, how many remain uncorrected.

- Cost and schedule

performance—how many activities per period

were completed with significant variances.

8.3.3 Outputs from

Quality Control

.1 Quality improvement.

Quality improvement is described in Section

8.2.3.1.

.2 Acceptance decisions. The

items inspected will be either accepted or rejected.

Rejected items may require rework (described in Section

8.3.3.3).

.3 Rework. Rework is

action taken to bring a defective or non-conforming item

into compliance with requirements or specifications.

Rework, especially unanticipated rework, is a frequent

cause of project overruns in most application areas. The

project team should make every reasonable effort to

minimize rework.

.4 Completed checklists. See

Section 8.1.3.3. When checklists are used, the completed

checklists should become part of the project’s

records.

.5 Process adjustments. Process

adjustments involve immediate corrective or preventive

action as a result of quality control measurements. In

some cases, the process adjustment may need to be handled

according to procedures for overall change control, as

described in Section 4.3.

|