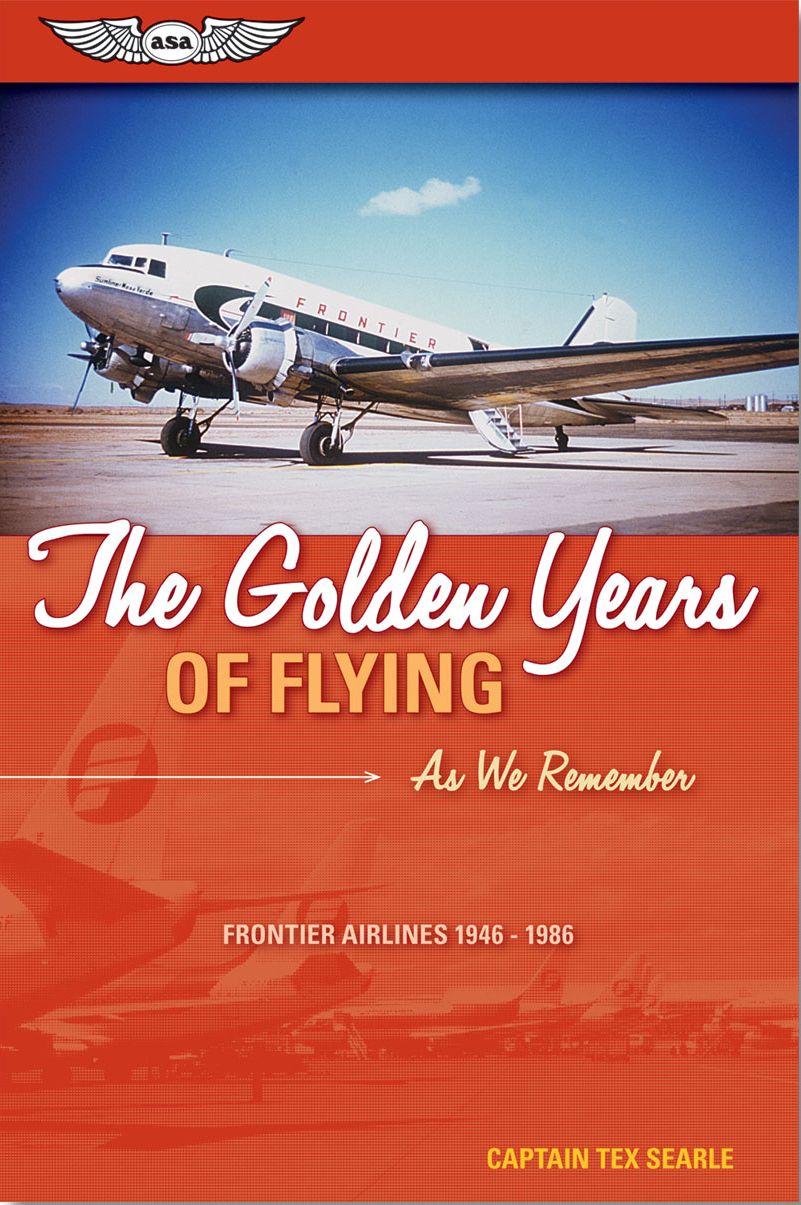

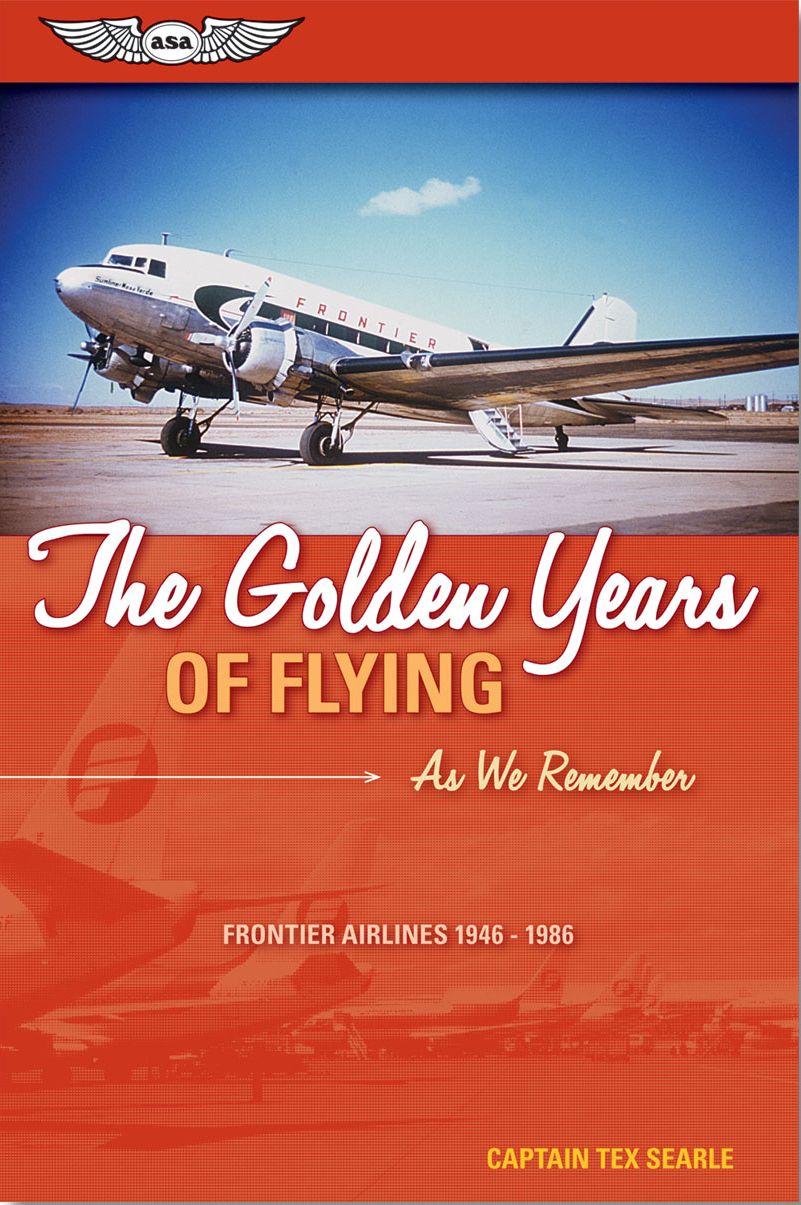

EXCERPTED FROM “THE GOLDEN YEARS OF FLYING”

By Old Frontier Airlines Captain Tex Searle with his kind permission

and his publisher Aviation Supplies & Academics (copyright

2009).

His grand memoir is for sale at Amazon.com and ASA

|

THE SMOKE DETECTOR Captain Graham began his airline career in April of 1948 as a steward for Monarch Airlines based in Denver. Before the merger in 1950, stewards were assigned on all three of Frontier’s predecessor airlines until Challenger began hiring stewardesses in July of 1948. Besides cabin duties the stewards had the added responsibility of entering compartment A (baggage-mail-cargo aft of cabin) during flight to check and rearrange the mail sacks for the various stops, similar to what the old railroad mail agents used to do. Graham still laughs about a particular trip when he was serving as steward. At the time the DC-3 was at max climb performance to reach 13,000 feet in order to clear the Uncompahgre Plateau when I hurried aft to sort out the mail sacks before compartment A (commonly known as comp-A) became cold-soaked from the frigid temperatures awaiting us at the higher altitudes. When I turned the handle on the door to return to the warm inviting cabin, it wouldn’t open. I thought about the long flight at 13,000 feet with no heat, and all the unattended. passengers. I anxiously twisted the handle and pushed on the door to no avail. Not wanting to bust the door off its hinges for fear of scaring the passengers, (that’s my story, and I’m sticking to it) I lit up a cigarette and pondered my predicament while sitting on the mail sacks. My attention was drawn to the smoke detector that would signal to the flight deck crew of smoke or fire in comp-A, and a plan soon evolved to end my imprisonment. Taking a long drag I inhaled deeply, then blew smoke into the detector. Not long after, a wild-eyed copilot yanked the door open to stare at me as I calmly sat on the mail sacks and smoked my cigarette. His first words, “Graham! what in hell are you doing?” Later, the passengers informed me that when the call light lit up and there was no response, the cockpit door flew open and a wild eyed copilot rushed past them straight to the rear of the aircraft and, after some exerted effort, flung the door open. After I got the copilot calmed down and explained what had happened, his eyes gradually retained a glassy expression that seemed to say, “Why does this happen to me?” Shaking his head he returned to the cockpit. I can assure you that fire in flight is one of the most serious emergencies a crew can experience. Happily, this was a planned, false emergency, but the response was excellent. Captain Graham served as a combat air crewman in a navy patrol bomber during WWII. He used his GI education benefits to become an airline pilot. Well qualified, he was soon cleared to fly the right seat and not long after was promoted to captain and experienced a career full of the joys and trials of flying the Rocky Mountains. Captain Graham gave many hundreds of hours to help improve our chances to maintain the safest airline record in the world-wide history of civil aviation as the chairman of the Air Line Pilots Association safety committee. In 1983 Graham was forced to leave at the retirement age of sixty after a thirty-five-year career with Monarch/Frontier. But after spending so many years in the front office of the DC-3s and the jets that replaced them, he couldn’t give it up; so he continued on for another nine and one-half years flying for Fed X and UPS and delivered mail for contract carriers. He served as a charter pilot and hauled freight and flew fire patrol. Many times he flew into the back country on medical evacuation missions. Now retired, this captain who has just about done it all resides in Colorado. I NEVER GOT TIRED OF THAT Captain George Graham describes from his notes of ingrained memories flying the difficult and challenging routes throughout the mountain empire. Many times we earned every cent of our pay; and then there were flights that had us sitting on top of the world viewing large scrolls of magnificent landscapes unfolding before us. I never got tired of that. The Grand ‘Ole Lady had you down there where you could see everything close up sitting in the best seats in the house. The jets are nice but they’ll never come close to the DC-3 in offering breathtaking views of nature at its best. In those days the passengers had their noses pressed to the windows. Now days they read a book. How well I remember the years when we took off from Denver into the early dawn on the first leg of trip 31. When departing Pueblo, (it seems like only yesterday), we had to convince the DC-3 to make a max climb effort to clear the backbone of the Continental Divide. In the cool mountain air we skimmed through the eminent Monarch Pass (the airline’s namesake) while we continually surveyed the high terrain with suspicion. Our adrenaline kept us alert to counter any assault this pass was notorious for. Counting seven peaks north we could see the lofty Mt. Elbert, the highest peak in Colorado at 14,431 feet. I was never without awe watching these numerous peaks slide by my side window. After exiting Monarch pass at its western extremity I would ease the throttles back to begin a slow let-down to lower elevations in an attempt to give our passengers ears more time to adjust. Proceeding on to the small airport at Gunnison, navigating was only a matter of maneuvering between the high, steep slopes of the canyon. From Gunnison we continued through Montrose, Colorado to Grand Junction, our turn around terminus. On the return trip from Grand Junction, if the mountain passes east of Gunnison had become obscured in clouds, the flight was forced to divert to what was known as the long way around. This alternate route provided H-markers for flying in inclement weather while making an end run through southern Colorado until we could turn northeast towards Denver. After clearing the high Chama pass, our course brought us to the Fort Garland H-marker which provided an invisible pathway into the confines of the towering La Veta pass. Flying by the gauges, we had to carefully crank the coffee-grinder to tune in the La Veta H-marker. During the twenty-four-mile flight between Fort Garland and La Veta, our undivided attention was directed at the instruments, and we continually made sure our directional gyros and the azimuth for the ADF pointers were aligned with the compass as we maneuvered the DC-3 through the narrow divide obscured in clouds. If there was thunderstorm activity in the area, the precipitation would cause our ADF needles to become useless as they hunted and rotated about the azimuth face. We then reverted to the old manual loop form of navigation to guide us through the pass. While flying the aircraft in turbulence with one hand, I would use the other hand to rotate the manual loop antenna to track the aural-null signals between the two H-markers. We have experienced cross-winds in that pass that would cause a crab into the wind as much as thirty degrees or more to maintain our track, and with magnetic disturbances that caused our compass to swing, we never had time to be scared but I’ll say one thing, “The pass was resplendent when we could observe the high panorama, but grossly offensive when mother nature had pulled a curtain across the entrance. Free from the environment of the Rocky Mountains the ol’ gal would put her head down as we headed for the home stretch. |

|

|

We are FLamily

|