Liberty: Entirely machine made patches using a technology developed a the turn of the century. First a strip of base material is fed into a loom then colored thread worked into it completing the design. Usually constructed of thin cotton, silk or artificial silk. As I said, these are very thin patches. They are called Liberty Loan patches because they were made available as part of a final war loan promotion. Liberty Loan patches were made available for sale at stateside px's and overseas embarkation points at the end of the war.

Service Stripes, Overseas, State Side, Others

A pilot that served for two years in the US training other aviators would be entitled to have 4 silver service chevrons. As time has gone on these are now quite tarnished and can be mistaken as tarnished gold chevrons. The difference between a two year AEF Pilot and a two year State Side pilot is substantial.

Wound Stripes

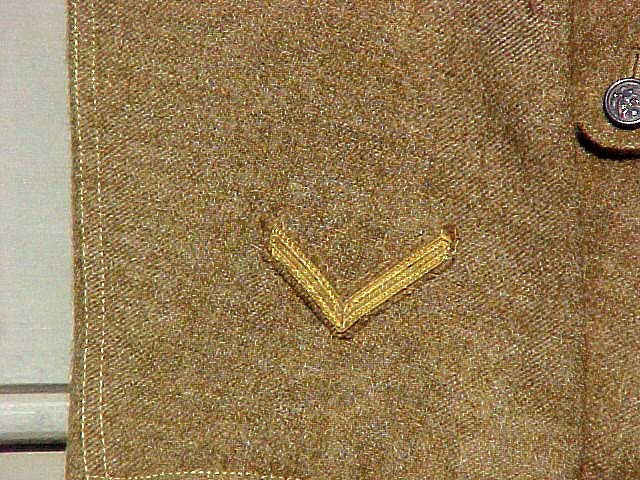

Rank Chevrons

Rank chevrons were worn on the right arm, mid way up the upper arm. They follow the standard Army rank designation, Cpl, Sgt., 1st Sgt. Etc.

At times the standard Army rank chevrons have the PFC badge incorporated as part of chevron. I suppose this was authorized, but not commonly practiced. There are also SGT chevrons with rating specialties embroidered in them as part of the badge. Once again these are not of the normal occurrence.

Be especially cautious of the aviation, tank or Chemical Warfare attachment on these chevrons. I have seen a lot of very new rating chevrons on rather worn uniforms. There are also batches of loose PFC rating badges floating around.

Honorable Discharge Chevron

This chevron indicated the wearer was honorably discharged from service. It is a red chevron worn normally point up in the mid to upper half of the left arm. I have also seen examples inverted like a "V" . These are often confused as a Pvt. Chevron but as I mentioned before there was no Private Chevron during WWI. These were placed on uniforms at the very end or even after completion of military service. Often they are missing or even found in a pocket never having been applied.

FakesI have been involved with collecting US WWI uniforms for nearly 15 years now and one thing that I am always asked is how to spot a fake. It is a serious subject of concern for all collectors. This has become particularly critical in that the outlay required to purchase WWI material has far exceeded the good old days where you could pick up a veterans complete trunk with all his souvenirs at a flea market for $50.00. Some of the more exotic groups have been bringing prices where an error in identifying a fake can hurt.

Fortunately in the WWI arena they are NOT faking the uniforms (US) yet. Unlike Civil War uniforms that are bringing such high dollars the work required to make a passable fake is just not worth it. However, with the popularity of the hobby it will most likely not be long till fakes begin to hit the market. Already there are reenactor's uniforms, better than 15 years old, have seen more battles than many originals.

Typically the common uniforms are not FAKED as such, they mostly fall to the age old scam of sweetening the deal. For sure some of the more exotic uniforms are now being assembled (faked) by very clever and knowledgeable con artists. Those I have seen prone to faking (because of the prices they bring) are US Air Service, 2nd Division USMC, Balloon Corps, Tankers, Gas and Flame Regiments, Chemical Corps, American Field Service, North Russia and Siberian troops.

There are several scenarios I consider when encountering a uniform or group that seems out of the ordinary.

1st is the uniform and/or group of materials associated with it is an outright forgery, put together by a dishonest scalawag bent on cheating the next owner.

2nd was this the product of a veteran that served but felt that he needed some post war changes to his original kit.

3rd does this uniform or group stand out because of things added to the group (embellishment). Does it consist of a conglomeration of kits put together to increase the desirability of the offering.

4th . Does the documentation and supporting information check out?

5th . Is this a true rarity.

The only way to begin to recognize original vs suspect (and some still slip through and gig even the most experienced collector) is to get your hands on and look at as many authentic uniforms as possible. Particularly focus on those with provenance.

The collector also needs to know their history. Become familiar with known authentic uniforms, types and arrangements of patches and decorations. What would have been authorized for specific units and so on. The story is detail, detail, detail, know what is correct and what wouldn't be logical for a uniform.

However, there are several schemes that are in practice to maximize the dollars from a otherwise ho-hum bunch of surplus WWI items. Usually the fall into one or more of the following arenas.

Faked or Reapplied Insignia

One of the most popular ways to beef up a uniform is to enhance or add the organizational insignia. It is up to the collector to make the decision if the insignia is original and if it is original to the uniform.

Some of the typical insignia scams are as follows

Faking the unit patch. The collector will soon realize that the unit patch or the specialty patch can make or break the desirability of any uniform. Tankers, 2nd Division, Aero Squadrons, 332 Inf., North Russian or Siberian Expedition patches all command major outlays if obtained on the open collector's market. Others do not command so much cash but always make a uniform more desirable if there is one present. The effort required add a patch may run from simply adding an original patch to a blank coat to meticulously manufacturing a fake highly desirable patch and then applying it. Not only are some of the rare patches being faked but patches that never were in existence are being invented.

Faking or Adding Collar Disks. The same is true for the collar disks. A uniform with the correct or rare collar disk is always more desirable than one with a mis-matched set, disks missing or fitted with the more common types. For several years now new made collar disks have been imported with no indicator that they are reproductions. As uniforms were discarded over the years collar disks were pulled off and have over time found their way into junk boxes and flea markets. Certain dealers specialize in supplying loose collar disks. When examining a uniform a collector must make the determination if the collar disks are period and if they are original to the uniform.

Re Assembling. When examining a uniform, the collector must make an assessment of its originality as an originally assembled unit. This is an important factor to consider, particularly if you are paying a premium for an original specimen of some rarity. In your assessment does the patch seem to be an original application. Does the collar disk look like it has been on the uniform for years. Do wound stripes seem original to the uniform. Are over seas stripes correct for the unit and do they look like they have been on the uniform for many years. The collector must make this determination prior to meeting the required purchase price.

Embellishments:

By far the most common practice. A rather generic coat, perhaps with some light mothing is married up with another gas mask, mess kit, helmet, some photos and a letter or two.. Sprinkle on some tales about it being out of the family and some third hand stories of adventures on the Western Front and shazamwe have a highly desirable intact group. The lot will now sell for considerable more than the individual parts due to its desirability as an intact surviving group belonging to one soldier.

This is not a big money maker for the run of the mill AEF soldier but make it an aviator, tanker or a North Russia group and embellishment makes the pot that much sweeter.

Creations:

Some what common if a supplier has a bundle of mundane material and one or two nice pieces. Usually done with high dollar items. The scam is to take one good piece add a bunch of junk and make it a really nice group.(With a corresponding REALLY nice price). For example, you have an aviator's wing non identified which is authentic. Put it on a uniform, add a nice First Army patch with a aviation rhondel. Sprinkle in a few common period photos (even non military). Add a period footlocker, gloves, souvenir post card album and boy "datsa nice bunch of stuff". It is now also selling for 2 to 3 times what the wing is worth and it is the only thing that has any worth. I have seen a wing worth say $1,000 coupled with $200 worth of other period material for nearly $3,000.

Defense:

The best defense by all means is to know your stuff. However below are a few questions that every one wanting to invest in a WWI uniform should ask themselves while considering a selection.

Is the insignia/patch authentic, is it original and is it original to the uniform. Stitching is not necessarily an indicator since authentic uniforms bear witness to a wide variety of stitching from crude to near embroidery. More important is the insignia indented in the cloth or sit on top? Is there a different odor? If there is insignia originally on a uniform it should have weathered the same as the rest of the group. Is it appropriate for the uniform.

Is the collar brass authentic. Does the collar brass match, particularly in color and ware. Are they appropriate for the uniform being examined. Does the screw post look like it has been undisturbed? Is the wool under the collar brass indented and match the impression left by the disk? I like to look for a little "Green" around the post and under the disk. If the uniform was worn and the sweat from the soldier's neck got under it may have a nice green corroded color.

Does the overall condition of the uniform and accompanying artifacts match. Even if every thing sat in a closet or was packed away in a trunk it should have had a uniform exposure to its surroundings. A brand new cap gas mask or cap with a worn uniform would lend suspicion to the groups integrity.

Does the dealer have a reputation (good or bad). This is paramount. Do not deal with known crooks, ask fellow collectors about a dealer's reputation. If a dealer that lacks integrity obtains a group it must be considered suspect. Do not sell to crooks, they will break up groups, enhance them and then use YOUR name to lend integrity to the group.

This may effect a return on your investment far into the future. A recent sell off of a known suspicious CW dealer brought the chickens home to roost. John Bracken, a dealer with a dubious reputation auctioned a load of material off at a well known NY auction house. Even though many of his items had was some would consider "Fool Proof" provenance the auction brought only pennies on the dollar because of his reputation. Folks were afraid to touch it and the auction realized tens of thousands less than the auction house predicted.

Blue Light: Does the uniform pass the blue light test. A black light may show up a translucent glow if the material in the uniform or patch is of current production. To be warned, this is not a full proof test and may lead the buyer to a false sense of security.

This sort of information cannot be obtained from collector's books, only by handling a lot of uniforms and noticing the dinky details.

=====================END=============================

Bibliography:

America's Munitions: 1917-1918. Report by Benedict Crowell, Ass.t Sec. Of War, Director of Munitions. Washington GPO, 1919.

Military Collector & Historian, Journal of the Company of Military Historians, Wash. DC. Vol XXXV #3 (Fall 1983). Vol. XXXV #2 (Summer 1983), Vol. XXXIV #4 (Winter 1982).

Insignia of the A.E.F., George O. Morgan, Mark Warren. Hill Printing Co. Keokuk, IA. 1986

World War One Collector's Handbook, Paul Schulz, Hayes Otoupalik, Dennis Gordon. Private Publication by the Authors, Missoula Montana,1979.

Manual for the Quarter Master Corps, U.S. Army Vol. I & II 1916, U.S. Government, Rev, 1917.