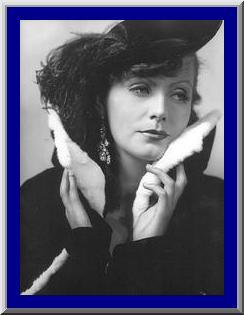

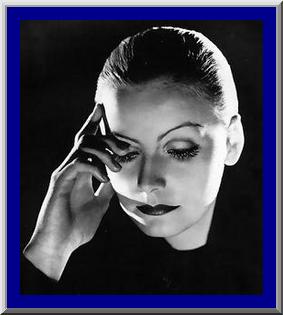

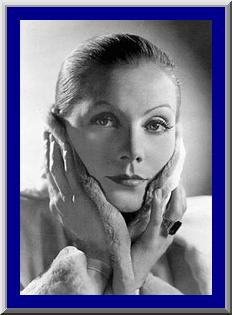

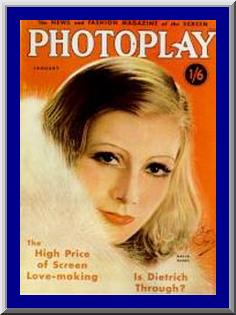

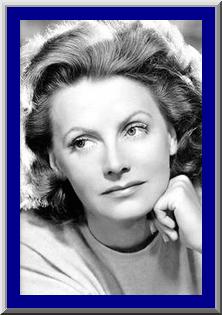

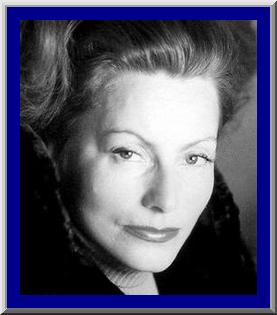

In 1923, Stiller cast Garbo in The Atonement of Gosta Berling, an overlong but internationally successful film which made her a minor star. The director became Garbo's mentor, glamorizing her image and changing her professional name to Garbo. On the strength of Gosta Berling, Garbo was cast in the important German film drama The Joyless Street in 1925, which was directed by G. W. Pabst. Hollywood's MGM studios, seeking to "raid" the European film industry and spirit away its top talents, then signed Maurice Stiller to a contract. MGM head Louis Mayer was unimpressed by Garbo's two starring roles, but Stiller insisted on bringing her to America, thus Mayer had to contract her as well. The actress spent most of 1925 posing for nonsensical publicity photos which endeavored to create a "mystery woman" image for her (a campaign that had worked for previous foreign film actresses like Pola Negri), but it was only after shooting commenced on Garbo's first American film, The Torrent (1926), that MGM realized it had a potential gold mine on its hands. As Maurice Stiller withered on the vine due to continual clashes with the MGM brass, Garbo's star ascended. But MGM refused to pay her commensurate to her worth, so Garbo threatened to walk out; the studio counter-threatened to have the actress deported, but in the end they buckled under and increased her salary. In 1927 Garbo co-starred with John Gilbert in Flesh and the Devil, and it became obvious that theirs was not a mere movie romance. The Garbo/Gilbert team went on to make an adaptation of Tolstoy's Anna Karenina titled Love. Its original title was Heat, but this was scrapped to avoid an embarrassing ad campaign which would have started with "John Gilbert and Greta Garbo in...". The couple planned to marry, but Garbo, in one of her frequent attacks of self-imposed solitude, did not show up for the wedding; over the years the actress would have other romantic involvements, but she never would marry. In 1930, MGM's concerns that Garbo's thick Swedish accent would not register well in talkies were abated by the success of Anna Christie, which was heralded with the famous ad tag "Garbo Talks." Some noted that the slogan could also have been "Garbo Acts," for the advent of talkies obliged the actress to drop the "mysterious temptress" characterization she'd used in silents in favor of more richly textured performances as worldly, somewhat melancholy women to whom the normal pleasures of love and contentment would always be just out of reach. In this vein, Garbo starred in Grand Hotel (1932), Queen Christina (1933), Anna Karenina (1935) and Camille (1936), which served to increase her worshipful fan following. Each vehicle also increased her star power. Garbo was allowed a latitude not afforded her contemporaries of that era. Other actresses coveted the attention and respect that Garbo had earned. The actress's legendary aloofness and desire to "be alone" (a phrase she used often in her films, once to comic effect in Ninotchka) added to her appeal, though less starry-eyed observers like radio comedians and animated-cartoon directors found Garbo a convenient target for satire and lampoon. Always more popular overseas than in the U.S., Garbo became less and less a moneymaker as the war clouds gathered in Europe; this was briefly stemmed by Ninotchka (1939), a bubbly comedy which was advertised Anna Christie style with "Garbo Laughs." But by 1940, it was clear that the valuable European market would soon be lost, as would Garbo's biggest following. The actress's last film, Two Faced Woman (1941), was a pedestrian domestic comedy that some observers believe was deliberately badly made by MGM in order to kill her career. Actually it wasn't any worse than several other comedies of its period, but for Garbo it was a distinct step downward. She retired from movies directly after Two Faced Woman, and though she came close to returning to films with Hitchcock's The Paradine Case (1947), she opted instead for total and permanent retirement. A millionaire many times over, Garbo had no need to act, nor any desire to conduct an active social life. She traveled frequently, but always incognito. This didn't stop photographers from ferreting her out. A solitary woman but not really a recluse, Garbo could frequently be spotted strolling the streets near her New York apartment; in fact, "Garbo sightings" became as much a topic of conversation in some icon-worshipping circles as "Elvis sightings" would be in the 1970s, the major difference being of course that Garbo was alive to be sighted. Even after her death in 1990, the legend of Greta Garbo was undiminished. Few of her fans talk of her in human terms; to her devotees, Greta Garbo was not so much Film Legend as Film Goddess.

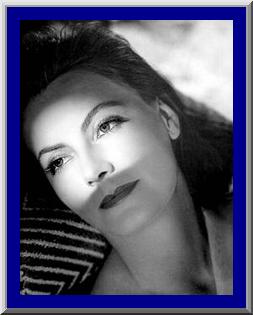

Greta Lovisa Gustafsson was born in Stockholm, Sweden on September 18, 1905. Garbo grew up in a rundown Stockholm district, the daughter of an itinerant laborer. She was 14 when her father died, leaving the family destitute. In school, Garbo did little to distinguish herself, and she was forced to leave school and go to work in a department store. Few who knew Swedish actress Greta Garbo in her formative years would have predicted the illustrious career that awaited her.

As a youth she photographed beautifully, but she had no film aspirations until she appeared in an advertising short at that same department store while she was still a teenager. Her first film, a 1921 publicity short financed by her employers, was titled How Not to Dress. Garbo followed this first movie appearance with Our Daily Bread, a one-reel commercial for a local bakery.

Then she played a bathing beauty in a 1922 two-reel comedy, Luffar Peter (Peter the Tramp). Billed under her own last name, Gustaffson, Garbo gained a couple of good trade reviews, and also enough confidence to seek out and win a scholarship to the Royal Dramatic Theatre. While studying acting, she was spotted by director Mauritz Stiller, who in the early '20s was Sweden's foremost filmmaker.