Bewitched by a Cause

Dick York Is Dying of Emphysema but He Lives to Help the Homeless

By BOB SECTER, Times Staff Writer

![]() ROCKFORD, Mich.--In the make-believe world that made Dick York famous, his troubles would have been magically swept away with the twitch of a nose or the wave of a wand.

ROCKFORD, Mich.--In the make-believe world that made Dick York famous, his troubles would have been magically swept away with the twitch of a nose or the wave of a wand.

![]() But no television sitcom medicine can cure what ails York, who played Darrin Stephens, the harried, mortal husband of the comely witch, Samantha, in the hit series "Bewitched" more than two decades ago.

But no television sitcom medicine can cure what ails York, who played Darrin Stephens, the harried, mortal husband of the comely witch, Samantha, in the hit series "Bewitched" more than two decades ago.

![]() He shook off an addiction to painkillers but could not shake the chronic agony of a crippling spine injury or the aftereffects of a multipack-a-day cigarette habit. Nor could he elude the bank and bill collectors, who foreclosed on his West Covina home and sapped his life savings.

He shook off an addiction to painkillers but could not shake the chronic agony of a crippling spine injury or the aftereffects of a multipack-a-day cigarette habit. Nor could he elude the bank and bill collectors, who foreclosed on his West Covina home and sapped his life savings.

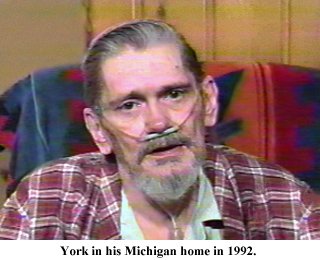

![]() These days, York is broke, bedridden and slowly dying of emphysema. He lives with his wife, Joan, on a $650-a-month Screen Actors Guild pension in the tiny red bungalow near Grand Rapids, Mich., that once beloged to in-laws.

These days, York is broke, bedridden and slowly dying of emphysema. He lives with his wife, Joan, on a $650-a-month Screen Actors Guild pension in the tiny red bungalow near Grand Rapids, Mich., that once beloged to in-laws.

![]() Still, this is not a sad story, because York is not a sad person or one to dwell in self-pity, Exuberant, excited, bursting with energy for someone whose slightest steps send him gasping for air, the 60-year-old actor has found one last part to play--the role of his life--as a one-man clearinghouse for aid to the homeless.

Still, this is not a sad story, because York is not a sad person or one to dwell in self-pity, Exuberant, excited, bursting with energy for someone whose slightest steps send him gasping for air, the 60-year-old actor has found one last part to play--the role of his life--as a one-man clearinghouse for aid to the homeless.

![]() Tethered to an oxygen tank and housebound for months, York spends hours on the phone each day chatting up radio talk show hosts, bureaucrats and just about anybody else who will listen to publicize the plight of street people and scrounge tons of clothes, food and bedding from government supplies.

Tethered to an oxygen tank and housebound for months, York spends hours on the phone each day chatting up radio talk show hosts, bureaucrats and just about anybody else who will listen to publicize the plight of street people and scrounge tons of clothes, food and bedding from government supplies.

![]() He may be an invalid in body, but not in spirit.

He may be an invalid in body, but not in spirit.

'Just My Body That's Dying'

![]() "I feel wonderful--it's just my body that's dying," he says with a raspy cackle and that slightly goofy Darrin Stephens grin stretched broad across his face. " ... You know, three whales get in trouble and people from all over volunteer to help. Wouldn't it be wonderful if one old has-been actor with a hose up his nose could help millions of people?"

"I feel wonderful--it's just my body that's dying," he says with a raspy cackle and that slightly goofy Darrin Stephens grin stretched broad across his face. " ... You know, three whales get in trouble and people from all over volunteer to help. Wouldn't it be wonderful if one old has-been actor with a hose up his nose could help millions of people?"

![]() Social workers from Detroit to Chicago say York has become a master at cutting bureaucratic mazes to scare up thousands of surplus military- and civilian-issue coats, cots, mattresses, sleeping bags, boots and other supplies long buried, and ripe for the taking, in government warehouses.

Social workers from Detroit to Chicago say York has become a master at cutting bureaucratic mazes to scare up thousands of surplus military- and civilian-issue coats, cots, mattresses, sleeping bags, boots and other supplies long buried, and ripe for the taking, in government warehouses.

![]() "But his greatest contribution is heightening awareness of this problem nationally," said James Nauta, a Salvation Army official based in Grand Rapids. "He's very ill but he finds his way around the country by phone. People listen. When he talks, they respond."

"But his greatest contribution is heightening awareness of this problem nationally," said James Nauta, a Salvation Army official based in Grand Rapids. "He's very ill but he finds his way around the country by phone. People listen. When he talks, they respond."

![]() Champion for the downtrodden is a part for which York was typecast. He was a child of the Depression whose family faced a constant struggle to stay off the streets.

Champion for the downtrodden is a part for which York was typecast. He was a child of the Depression whose family faced a constant struggle to stay off the streets.

![]() He was raised on Chicago's Near North Side in what now is a chic neighborhood of town homes and condominiums but then was mostly tenements. His parents often were out of work and broke. When they did not have the rent-- which was often--someone had to stay in the family flat at all times to prevent the landlord from locking everybody else out.

He was raised on Chicago's Near North Side in what now is a chic neighborhood of town homes and condominiums but then was mostly tenements. His parents often were out of work and broke. When they did not have the rent-- which was often--someone had to stay in the family flat at all times to prevent the landlord from locking everybody else out.

![]() As a boy, York saw his father struggle with other men for food discarded in a garbage can. When he was 11, an infant brother died but the family could not afford to bury him. So York and his father slipped into a graveyard at night and laid the youngster to rest in a coffin crafted from a shoe box.

As a boy, York saw his father struggle with other men for food discarded in a garbage can. When he was 11, an infant brother died but the family could not afford to bury him. So York and his father slipped into a graveyard at night and laid the youngster to rest in a coffin crafted from a shoe box.

![]() Despite such hardships, York remembers his childhood as a happy time, influenced most profoundly, odd to say, by something he read in a Tarzan adventure.

Despite such hardships, York remembers his childhood as a happy time, influenced most profoundly, odd to say, by something he read in a Tarzan adventure.

![]() "There's Tarzan captured in the land of the Fire Queen and ready to be sacrificed," York recalled. "He's tied up hand and foot and being carried up to the sacrificial altar. He's surrounded by 5,000 of these fierce beast-like characters and a knife is about to be plunged into is heart and somebody says to him, 'My God, Tarzan, why are you smiling?' And Tarzan says,'Because I'm alive.' "

"There's Tarzan captured in the land of the Fire Queen and ready to be sacrificed," York recalled. "He's tied up hand and foot and being carried up to the sacrificial altar. He's surrounded by 5,000 of these fierce beast-like characters and a knife is about to be plunged into is heart and somebody says to him, 'My God, Tarzan, why are you smiling?' And Tarzan says,'Because I'm alive.' "

![]() Besides a cheery personality, York also had a beautiful boy soprano singing voice. A nun at St. Mary of the Lake school sent him to a singing coach, who in turn sent him to the Jack and Jill players, a training school for young radio and stage actors. Through Jack and Jill, he performed in dramas and public service programs on local radio stations. By the time he was 15, York starred in his own network radio show, "That Brewster Boy," on CBS. That was the year he also met Joan, his wife-to-be, another child radio star.

Besides a cheery personality, York also had a beautiful boy soprano singing voice. A nun at St. Mary of the Lake school sent him to a singing coach, who in turn sent him to the Jack and Jill players, a training school for young radio and stage actors. Through Jack and Jill, he performed in dramas and public service programs on local radio stations. By the time he was 15, York starred in his own network radio show, "That Brewster Boy," on CBS. That was the year he also met Joan, his wife-to-be, another child radio star.

Life-Changing Role

![]()

![]() He did thousands of radio shows in Chicago and New York, graduating to television and Broadway, where his credits include "Tea and Sympathy" and "Bus Stop." He also had supporting parts in several films, most notably as the young schoolteacher hounded by religious fundamentalists in "Inherit the Wind" with Spencer Tracy, Fredric March and Gene Kelly.

He did thousands of radio shows in Chicago and New York, graduating to television and Broadway, where his credits include "Tea and Sympathy" and "Bus Stop." He also had supporting parts in several films, most notably as the young schoolteacher hounded by religious fundamentalists in "Inherit the Wind" with Spencer Tracy, Fredric March and Gene Kelly.

![]() A 1958 film, "They Came to Cordura" with Gary Cooper, proved, for York at least, to be his most memorable role. On the second to last day of shooting, York and several other actors were doing a scene that required them to lift a railroad handcar. At one point, the director yelled "cut" and everybody but York let go. The car fell on him and his spine was wrenched and the muscles around it torn.

A 1958 film, "They Came to Cordura" with Gary Cooper, proved, for York at least, to be his most memorable role. On the second to last day of shooting, York and several other actors were doing a scene that required them to lift a railroad handcar. At one point, the director yelled "cut" and everybody but York let go. The car fell on him and his spine was wrenched and the muscles around it torn.

![]() He worked through the pain rather than seek medical attention.

He worked through the pain rather than seek medical attention.

![]() He kept working for years, though the discs in his spine slowly crumbled. Over the years, he shrunk from more than 6-toot-i to 5-foot-10 or so and gradually became hunched.

He kept working for years, though the discs in his spine slowly crumbled. Over the years, he shrunk from more than 6-toot-i to 5-foot-10 or so and gradually became hunched.

![]() By the time "Bewitched" premiered in 1964, York took heavy doses of painkillers, sleeping pills, cortisone and other medicines--but only after he was done with each day's shoot and never while he was working, he is quick to stress.

By the time "Bewitched" premiered in 1964, York took heavy doses of painkillers, sleeping pills, cortisone and other medicines--but only after he was done with each day's shoot and never while he was working, he is quick to stress.

![]() Still, his dependence on drugs grew, and, in 1969, he went into convulsions on the set, woke up in the hospital and was replaced on the show by another actor. He never returned.

Still, his dependence on drugs grew, and, in 1969, he went into convulsions on the set, woke up in the hospital and was replaced on the show by another actor. He never returned.

![]() For the next 18 months, York stayed at home in bed in what he now admits was a drug-induced haze, as he tried to deaden his pain and heal his back. Finally, appalled by his stupor, he decided to go cold turkey. He moved in with his mother, who then lived in Buena Park, to spare his five children.

For the next 18 months, York stayed at home in bed in what he now admits was a drug-induced haze, as he tried to deaden his pain and heal his back. Finally, appalled by his stupor, he decided to go cold turkey. He moved in with his mother, who then lived in Buena Park, to spare his five children.

'Bagpipes Night and Day'

![]() "I had a band playing in my head, bagpipes night and day," York recalled. "It just went on and on and on and on and on.... The fans whisper to you and the walls whisper to you and you look at television and sometimes it flashes in a certain way that sends you into a fit and you know that your wife has put her hand in your mouth so you won't bite off your tongue. You can't sleep. You hallucinate. I used to make a tape recording of rain so I could listen to the rain lying in bed at night to drown out those damned bagpipes."

"I had a band playing in my head, bagpipes night and day," York recalled. "It just went on and on and on and on and on.... The fans whisper to you and the walls whisper to you and you look at television and sometimes it flashes in a certain way that sends you into a fit and you know that your wife has put her hand in your mouth so you won't bite off your tongue. You can't sleep. You hallucinate. I used to make a tape recording of rain so I could listen to the rain lying in bed at night to drown out those damned bagpipes."

![]() After six months, York was relieved when the hallucinations stopped and the ordinary pain returned.

After six months, York was relieved when the hallucinations stopped and the ordinary pain returned.

![]() Eventually, the Yorks took what was left of their savings and bought an apartment building in West Covina where they planned to live out their lives quietly.

Eventually, the Yorks took what was left of their savings and bought an apartment building in West Covina where they planned to live out their lives quietly.

![]() But when tenants had difficulty paying the rent, York, mindful of his own youth, could not bring himself to evict them. Short of cash himself, he missed mortgage payments and the bank foreclosed. The Yorks held on to their apartment by cleaning other units in the building they once owned. In 1976, the actor who once earned a six-figure salary got his first welfare check.

But when tenants had difficulty paying the rent, York, mindful of his own youth, could not bring himself to evict them. Short of cash himself, he missed mortgage payments and the bank foreclosed. The Yorks held on to their apartment by cleaning other units in the building they once owned. In 1976, the actor who once earned a six-figure salary got his first welfare check.

![]()

![]() When Joan's father died three years ago, the couple, whose children were now grown, flew to Rockford for the funeral. York's emphysema worsened; he collapsed in the yard of his in-laws' home. He never returned to California, but it was, in a sense, the start of his comeback.

When Joan's father died three years ago, the couple, whose children were now grown, flew to Rockford for the funeral. York's emphysema worsened; he collapsed in the yard of his in-laws' home. He never returned to California, but it was, in a sense, the start of his comeback.

![]() Not long after his attack, a friend asked him to record inspirational tapes for a young Chicago girl who had been in a coma for years. He did more and more tapes for other shut-ins, just pressing the button on his recorder and saying whatever came to mind.

Not long after his attack, a friend asked him to record inspirational tapes for a young Chicago girl who had been in a coma for years. He did more and more tapes for other shut-ins, just pressing the button on his recorder and saying whatever came to mind.

Efforts Began

![]() He read up on the McKinney Act, a federal law that was supposed to set up government surplus giveaway programs but was underused because of red tape. Then York, trading on his celebrity, started badgering bureaucrats and volunteers, first to find out what was in storage, then to figure how to shake it loose, and last, to transport it to shelters in need.

He read up on the McKinney Act, a federal law that was supposed to set up government surplus giveaway programs but was underused because of red tape. Then York, trading on his celebrity, started badgering bureaucrats and volunteers, first to find out what was in storage, then to figure how to shake it loose, and last, to transport it to shelters in need.

![]() Last year, he pried loose enough for 15,000 changes of clothes--second-hand pants, shirts, boots, socks, belts, field jackets and more--from Army surplus stocks in Illinois; he worked to get thousands of mattresses and blankets stored in Wisconsin. Through his calls, thousands of blankets and cots were moved from a federal facility in Lansing, Mich., for distribution to Detroit's homeless.

Last year, he pried loose enough for 15,000 changes of clothes--second-hand pants, shirts, boots, socks, belts, field jackets and more--from Army surplus stocks in Illinois; he worked to get thousands of mattresses and blankets stored in Wisconsin. Through his calls, thousands of blankets and cots were moved from a federal facility in Lansing, Mich., for distribution to Detroit's homeless.

![]() Sometimes, his efforts surprise not only the charities but York himself. Last year, he told a friend there was a desperate need by the homeless for underwear. In weeks, thousands of pairs of panty hose-- good for warmth regardless of the wearer's sex--showed up at the Dwelling Place, a Grand Rapids Shelter. Similarly, 5,000 cans of orange juice concentrate were delivered to the Salvation Army in Grand Rapids after York spread the word among friends and in interviews that shelter dwellers did not get enough vitamins. "I don't know how he does it," said Ron Still, an activist for the homeless in Reno, Nev., who has worked with York. "I don't question him. But more power to him." York calls his organization Acting for Life, but it consists of little more than a few friends across the country, a mail drop (P.O. Box 499, Rockford Mich. 49341), a telephone and the moxie of a dying man possessed.

Sometimes, his efforts surprise not only the charities but York himself. Last year, he told a friend there was a desperate need by the homeless for underwear. In weeks, thousands of pairs of panty hose-- good for warmth regardless of the wearer's sex--showed up at the Dwelling Place, a Grand Rapids Shelter. Similarly, 5,000 cans of orange juice concentrate were delivered to the Salvation Army in Grand Rapids after York spread the word among friends and in interviews that shelter dwellers did not get enough vitamins. "I don't know how he does it," said Ron Still, an activist for the homeless in Reno, Nev., who has worked with York. "I don't question him. But more power to him." York calls his organization Acting for Life, but it consists of little more than a few friends across the country, a mail drop (P.O. Box 499, Rockford Mich. 49341), a telephone and the moxie of a dying man possessed.

*Article dated 1992