Thoughts on National Character

An Article on the lost episode reconstructions

![]()

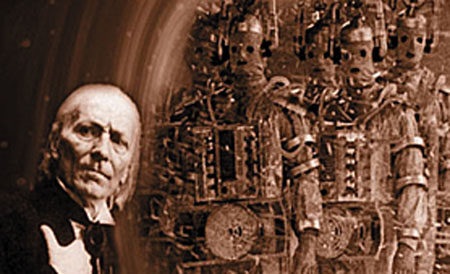

Reconstructing England's Time Lord

Between 1971 and 1978 the BBC burned 135 episodes of its long-running SF show Doctor Who. Since that time, only about twenty have been recovered. Rumors abound of missing episodes still existing in the hands of collectors, in television archives abroad, or in the hands of former BBC employees who rescued them from being junked, but no new finds have been made since 1993, when a four part story from the show's fifth season was found complete in the vaults of a TV station in Ghana.

The presumed non-existence of nearly one quarter of the series run has - uniquely among cult TV shows - given fans of the series a Cause, and while Who fandom has its share of the usual pointless conventions, cruises, fan fiction and the like, a small group of fans are using their time and talents to useful ends: the recovery, or, should recovery prove impossible, reconstruction of the missing episodes.

Created in 1963 by Sidney Newman (who at about the same time created another runaway hit, The Avengers) and originally starring character actor William Hartnell in the title role, Doctor Who is a science fiction soap opera geared to children, though from the very beginning it had an enthusiastic adult audience as well. A single story lasted between four and six weeks on average; with its cliffhanger structure, eccentric hero and a virtual parade of monsters it quickly became a Saturday night ritual on British television that lasted nearly thirty years.

It is a show that requires a certain amount of willing participation from its audience -- the low production values, unconvincing monsters and wandering scripts would try the patience of many -- but viewers who invest a spark of their own whimsy will find that the show fires on that spark and feeds it with its own eccentricity and a sense of healthy, gentle sedition.

That "willing participation" reached a new level in the early nineties with the discovery of a very complete series of "Telesnaps" - photographs of scenes from the missing episodes taken by professional photographer John Cura.

Cura, whose clients included actors, directors, and the BBC itself, made a business of setting his camera up in front of the television and snapping photos off the air. These were the days of live TV, and off-air photos were often the only record an actor or director had of their work. Many of Cura's Doctor Who photos were bound into volumes and stored at a remote BBC archive -- which is where they were found thirty years later.

Soundtracks of the missing episodes were already known to exist. Indeed, the BBC made commercial releases of this audio material at about the same time of the Telesnap discovery. It was only a matter of time before someone thought of combining the audios with the Telesnaps and existing video material (including film clips held by Australian censors) to "reconstruct" the missing episodes.

Working independently and, at first, unaware of each other, four fans (Richard Devlin, Robert Franks, Bruce Robinson and Michael Palmer) began reconstructing the shows on video between 1993 and 1995. At first their methods were primitive and the finished product reached an audience of as few as six people. Soon, though, computers, video editing software and cameras were brought into play, and the quality of the reconstructions improved. The four men later joined forces and under Robert Franks's supervision an internet-based distribution network was set up, with dubbing sites for the finished videos on two continents (the videos are free to anyone interested).

Rick Brindell, VP in charge of Marketing at Sterling & Sterling, a Long Island insurance agency, was a part of that distribution network from the start, but found the passive role he played in the project unsatisfying; last year he decided to try reconstructing a serial of his own.

"I actually had no video editing experience at all," Brindell says. "My first two attempts at The Macra Terror [a 1967 episode starring the late Patrick Troughton] failed as both times I had to rely on other people to do the 'work.' I did not have the equipment - video capture card, scanner, video editing software ... if I wanted to produce a recon, I would have to rely on myself alone. So I did some homework and went out and bought all the hardware and software I needed, and taught myself how to do it by trial and error."

Since then, under the name Loose Cannon Productions, Brindell has produced three more reconstructions and is working on a fourth. Reaction has been good, with the finished product reaching an audience of about 500 people and an enthusiastic reception.

Brindell spends between ten and twenty hours a week at his reconstruction work, "most of it after my wife has gone to bed. When I first started these projects my wife couldn't stand it as it takes up a lot of my free time. Now that I have gotten quite a bit of acclaim, she has realized that what I do is appreciated by fans everywhere. She is now very understanding."

Pre-production work, gathering the materials and planning their arrangement, takes up most of the time. "Then I scan the pictures and take the screen grabs with my 'snappy,' capture whatever clips there are and record the audio into the computer as a .wav file. I use Ulead's Media Pro video editing software to edit the episodes together frame by frame. This is very precise and tedious work. Many people have noted that I synch my clips with the audio extremely well, but it is made easy due to the software. Then I render the video editing program to an AVI file, which takes about 12 hours. Then I output to video tape."

Brindell's latest reconstruction, of 1965's The Myth Makers, required more than the usual degree of inventiveness -- and an element of Kismet. The story, a comedy, has The Doctor traveling back in time to ancient Greece and influencing history to the extent of suggesting and designing the Trojan Horse. Only seven photographs existed for the show, hardly enough to make a satisfying presentation. Screen grabs of the regular characters came from other episodes of the series, but the guest actors provided more difficulty. "I was able to get pictures of Agamemnon (Francis de Wolff) from a 1962 movie called Carry On Cleo. He actually wore the same costume as in Myth three years later. I was also able to get screen grabs of Max Adrian (King Priam) which came from the TV show Up Pompeii! and Frances White (Cassandra) from I, Claudius. Both were great finds due to the period costume. For the rest of the characters I had to use a different face to fit the voice as there were no good pictures for them. I used a variety of movies for scenery shots... the picture of the Greek camp came from Jason and the Argonauts. The picture of Troy came from Helen Of Troy. The crowd fight shot and the Greek fleet came from The Odyssey."

But the best find of all came as Brindell was finishing the reconstruction. "I had an email one day back in the beginning of July from a guy in England I did not know (Derek Handley). He told me that he was a friend of David Howe, who has written quite a few books on Doctor Who and who owns the actual Trojan Horse prop used in the production. He asked if I would like some pictures. I jumped all over that, believe me."

New video footage was taken of the horse, which stands just one meter high. "They decorated a picnic table with sand and a few branches and filmed the horse with a camcorder. Then they 'aged' the film to make it look 30 years old." In addition, new plans for the horse's construction were drawn up and photographed with a digital camera. "The 'actor' that played Hartnell's hands also had a replica Hartnell ring, to give it an authentic touch."

The finished product amounts to a new presentation and in some ways it's more interesting to see how Brindell has pieced together the filmclips, still photos and new material into a form that carries dramatic weight than it would have been to see the original episodes themselves. As with all Doctor Who, the reconstructions require some participation from the viewer but on the whole they are very successful at capturing the flavor of the series... and they allow fans of the show access to stories that would otherwise be known only from novelisations -- a poor substitute for a program that relies so heavily on the charisma of its actors.

Brindell believes that the BBC looks on the activities of the reconstructors with tacit indifference, and is unfazed by suggestions that his hard work might be rendered useless in coming years. "I do believe that some of the missing episodes exist somewhere," he says. "Probably sitting in someone's attic. Perhaps a TV exec died and the kids haven't gone through the personal possessions yet. However, I will not hold my breath. As far as I am concerned, I will never see them. This way I will not be disappointed. And now with the reconstructions, it's not as important."

To learn more about obtaining Doctor Who reconstructions, visit Rick's website at http://www.recons.com/From there you can link to Robert Franks's distribution site.