FIRST GENERATION

1. Gabriel GRASSET was born in France.

He was married to Louise in 1753. Gabriel GRASSET and Louise had the following children:

+2 i. Emmanuel GRASSIE.

SECOND GENERATION

2. Emmanuel GRASSIE was born in 1750 in PEI.

He was married to Genevieve CHEVARY. Genevieve CHEVARY was born in 1761. She died on Nov 12 1850. She was

buried on Nov 14 1850 in L'Ardoise, N.S.. Emmanuel GRASSIE and Genevieve CHEVARY had the following children:

+3 i. Laza

THIRD GENERATION

3. Lazare GRASSIE was born in 1786 in L'Ardoise, N.S.. He died on Jul 15 1856 in L'Ardoise, N.S..

He was married to Archange MATHIAS on Jan 12 1841 in L'Ardoise, N.S.. Archange MATHIAS was born in 1798 in

L'Ardoise, N.S.. She died on Jun 20 1877 in L'Ardoise, N.S.. Lazare GRASSIE and Archange MATHIAS had the following

children:

+4 i. Fidile GRASSIE.

FOURTH GENERATION

4. Fidile GRASSIE was born in 1818 in L'Ardoise, N.S.. He died on Dec 31 1902 in L'Ardoise, N.S..

He was married to Mathilda LEROUX (daughter of Philip LEROUX and Marguerite SAMSON). Mathilda LEROUX was born

in 1817 in L'Ardoise, N.S.. She died on Dec 2 1905 in L'Ardoise, N.S.. Fidile GRASSIE and Mathilda LEROUX had the following

children:

+5 i. Hubert GRASSIE.

FIFTH GENERATION

5. Hubert GRASSIE was born on Nov 2 1841 in L'Ardoise, N.S.. He died on Sep 19 1914 in L'Ardoise, N.S..

He was married to Adele Alexandrine SAMSON (daughter of Benjamin SAMSON II and Colombe BOUCHER) in L'Ardoise,

N.S.. Adele Alexandrine SAMSON was born on Jun 29 1848 in L'Ardoise, N.S.. She died on Jun 24 1937 in L'Ardoise, N.S..

She was buried on Jun 27 1937 in Mt.Calvery Cemetery, La'Ardoise. Hubert GRASSIE and Adele Alexandrine SAMSON had

the following children:

+6 i. Benjamin GRACIE.

SIXTH GENERATION

6. Benjamin GRACIE (photo) was born on Jun 1 1877 in Gracieville,NS.

He was married to Ida DEVOE (daughter of Captain Simon DEVOE and Margaret WALSH). Ida DEVOE (photo)

was born in Alder Point,NS. She died in Alder Point,NS. Benjamin GRACIE and Ida DEVOE had the following children:

+7 i. Hubert GRACIE.

+7 i. Hubert GRACIE.

SEVENTH GENERATION

7. Hubert GRACIE (photo) was born in May 1909 in Alder Point,NS. He died on Oct 22 1996 in Bras D'Or, NS.

He was married to Elsie FOUGERE (daughter of Simon FOUGERE and Victoria GRACIE). Elsie FOUGERE (photo) was

born on May 14 1915 in New Victoria, NS. Hubert GRACIE and Elsie FOUGERE had the following children:

+8 i. Rita Mae GRACIE.

9 ii. Louise GRACIE (photo).

10 iii. John GRACIE (photo).

11 iv. Earl GRACIE (photo).

+12 v. Bernard GRACIE.

Diane Gracie

Jean Gracie

Elizabeth (Betty) Gracie

Marie Gracie

Albert Gracie

Donald Gracie

Michael (Mickey) Gracie

Wallace (Wally) Gracie

MAurice Gracie

Francis Gracie

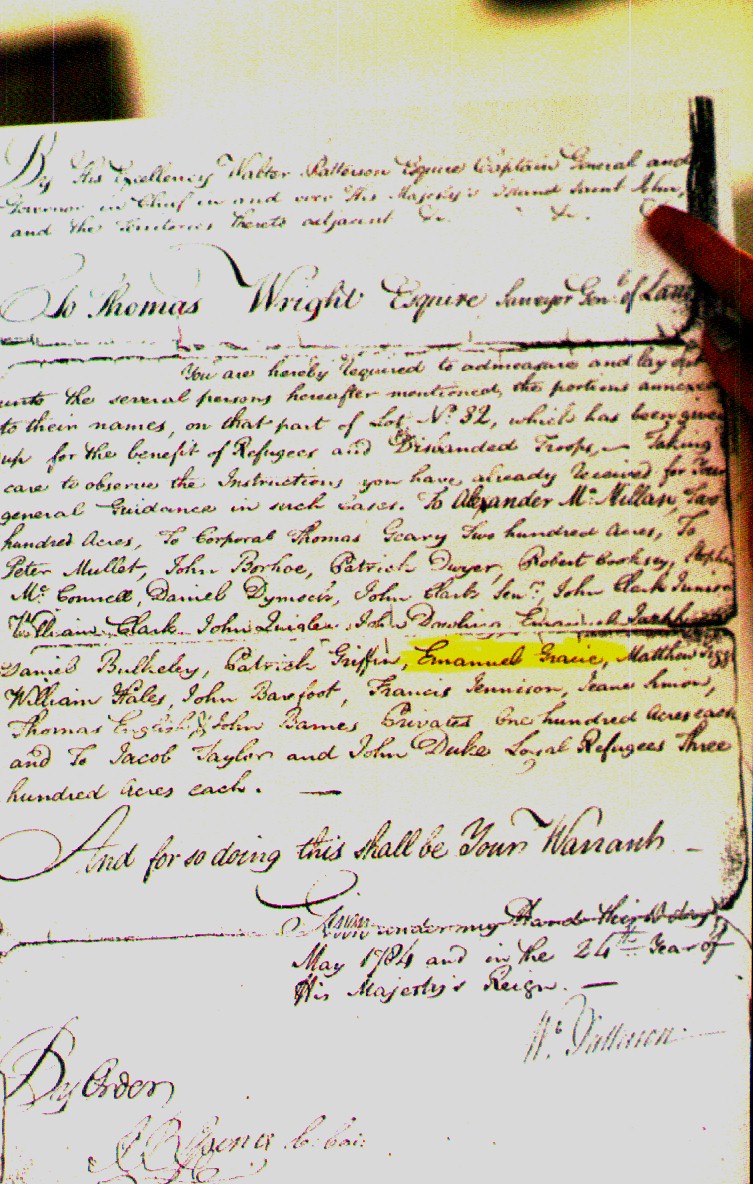

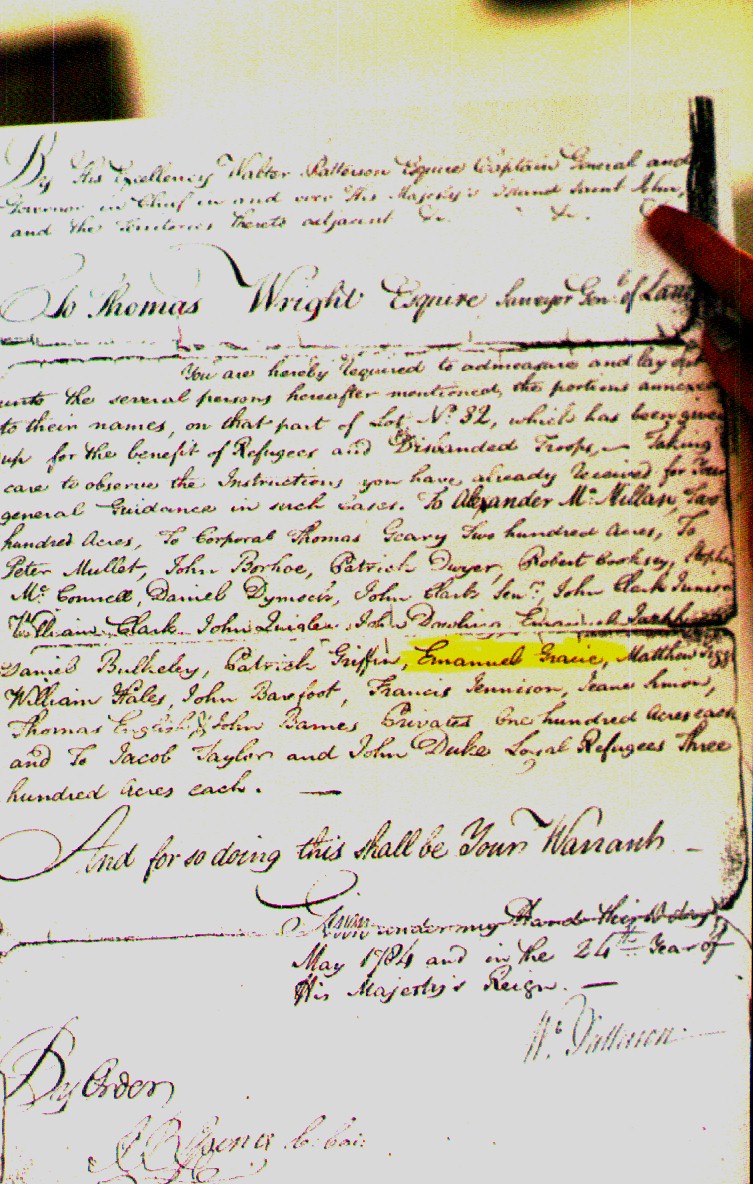

BELOW... COPY OF THE LAND GRANT, ISSUED TO EMMANUAL GRACIE

May, 1784 for 100 ACRES ON ST.JOHNS ISLAND ( P.E.ISLAND)

Captain Peter DeVaux (Pictured Above) MASTER MARINER 1832-1899 Peter was the son of Pierre and Colombe Landry who had come to the Little Bras d’Or from River Bourgeois in 1848; he married Charlotte Richard who was daughter of Francois-Regis and Angelique Dugas of that place. The ancestral home shown was built by Peter perhaps beginning in 1854, the year of his marriage. He initially bought land from his father-in-law, later increased his holdings in the area to several hundred acres with another hundred or so at St. Peter’s, Cape Breton. His beloved River Queen and several other schooners owned by him were built on that property along the Little Passage at Little Bras d’Or. In his forty years as a mariner the captain never lost a man to the sea.. As beautiful as anything man has made, built for strength and speed, yet strangely tender, were ships of sail. She was British built, Registry Number 74038, Port of Sydney; her designer, owner and skipper was Captain Peter deVaux, Acadian, Master Mariner. The River Queen was launched in the spring of 1876, fitted and ready for registration on the twenty-third of May. She was built in Bras d'Or at the family homestead, and slid from her ways into the Little Passage, about one hundred feet from the house which stands to this day. The registration papers indicate that Edmund Andrews was the builder, though his role was more likely that of overseer for insurance purposes, for family tradition has it that Peter and his sons built the schooner. Her papers show she was fifty-four feet long, had a beam of eighteen feet, depth of hold six feet seven inches, and her tonnage 32:26. According to a 1962 letter from Captain Peter's son Arthur I she was painted a "bottle green" above the water line, red-copper color below. Another source reported that she was built of lumber from the adjacent land of Captain Richard Richard (b. François-Regis Richard), Peter's father- in-Iaw. Son Arthur said the River Queen had a small cabin aft, with a stove to provide some comfort from the chill Atlantic winds of spring and fall. Her skipper had a canon concerning the fuel for this cast iron heat generator; though it was plentiful in the area, no coal. He stoked it with equally plentiful hardwood, and boasted the whitest sails in the fleet! Peter's role as a mariner was an evolution of circumstance. The degree to which he had become engaged in the fisheries would have been foreign to his ancestors at Beaubassin. Their means of livelihood centered around tillage rather than tillers, animal husbandry rather than codfishing. The bounty of the Fundy area lay behind the dyked marshes, the bounty of Cape Breton in the Atlantic. That is not to say the Fundy Acadians were not engaged in the fisheries, but as A. H. Clark says in his Acadia, "they were not of them to any great degree." The move of the family to Cape Breton late in the 18th century precluded significant agrarian pursuits, particularly with respect to the land in the Isle Madame area to which they had come; it provided no more than subsistence farming. The Arichat area did provide a training ground for the Atlantic fisheries and Peter, his father, siblings and cousins learned their lessons well, for after the move to the Bras d'Or area they owned some dozen schooners, sailed the Lakes and the Atlantic for over forty years, and never lost a man to the sea. The small schooners of Cape Breton, of which the Queen was one, were engaged in a variety of ways which included off-shore fishing, lobstering, freighting, and transportation of livestock. Peter was involved in all of these and according to his son Arthur he made at least one seal hunting voyage. He also remembers standing on the deck of the schooner with his father and Alexander Graham Bell while the two men discussed a freighting contract. Bell's summer home was at Baddeck on the Bras d'Or Lakes which, before the coming of the railroads, were the highways for those communities that dotted its shores. The larger schooners were one hundred feet or more in length, but they were relatively few in number compared to those between say forty and sixty feet, and the role played by the smaller vessels in the local economy was probably much greater. The River Queen made trips to Halifax through the St. Peter's Canal, which opened in 1869. She also visited ports in Prince Edward Island, at Arichat, other settlements along the southeast coast of mainland Nova Scotia and as well as the French islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon off the southeast coast of Newfoundland. A schooner of its size required a crew of but four or five, perhaps fewer when engaged in freighting on moderate seas, and Peter probably relied primarily on sons and nephews to man the Queen and his other schooners. Peter was no stranger to the harbour at Louisbourg, and on one occasion as her anchor was being raised for departure it caught on an old sea chest and brought it to the water's surface. Before it could be grasped it fell back to the sea. Great excitement ensued, for it was known that much booty, some of it gold, rested on the bottom of those waters, relics of the 18th century French presence there. One of the French vessels which sank in 1725 with all hands was Le Chameau and she was carrying considerable treasure for the payment of troops at Fort Louisbourg. The Queen's crew tried valiantly to re-capture the chest to no avail. Captain Peter marked the place with a buoy and returned three weeks later with a diver, but the buoy was gone. The story was told over and over again and a trip to this place always included efforts to again locate the object, with no further luck. In 1927 sons and nephews of Captain Peter made another try, spending many weeks searching for the wreck, repeating the effort the following summer, dragging and diving in the area. They gave up the search and never returned. In 1966 three young men, strangers to the original searchers, hit upon the wreck a short distance from where the earlier treasure hunters had worked. They were successful and recovered $700,000 in gold and silver coins. The Province of Nova Scotia got ten per cent, the deVaux family got not a sou. A great number of these small vessels engaged in a bit of smuggling from time to time, for whiskey could be bought at St. Pierre for a third of the cost in Cape Breton. Peter was not beyond indulging in the sport. One pleasant spring day his sister Sabine was entertaining two gentlemen who complimented her on the quality of the whiskey she served. She proudly told them that her brother had brought it from the French Islands and they, perhaps no less proudly, announced that they were revenue agents. Much to her dismay, they set out to where the Queen lay at anchor to confiscate the contraband. The good captain got word of the unintentional betrayal and moved to protect his illicit cargo. He discovered that the government agents had hired one Patrick O'Toole to guard the spirits aboard until such time as they could procure the transportation to remove the evidence needed for prosecution. Our grandfather engaged the Irishman in conversation suggesting he "have a nip before the whiskey was gone." As was the habit of this son of Erin, one drink led to another until O'Toole's value as a sentry was sharply reduced. The captain and his crew quickly moved the smuggled booty deep into the woods, much to the dismay of the guileful agents. Between 1853 and 1896 Captain Peter was the owner or part owner of four other schooners and for a period of five of those years was the part owner of one, the sole owner of two others. His first involvement, near the time of his marriage in 1854, was when he, his father Pierre, and his brother-in-law, Andre Dugas launched the 40' John William at Bras d'Or . Dugas held 22 of the 64 shares, Peter and his father 21 each; the vessel was named for the young sons of Andre and Pierre, respectively. The ownership of these ships was always divided into 64 shares, making possible a number of combinations of title, conveniently permitting one, the captain, to have a majority. In 1860 Peter and his father-in-Iaw Captain Richard launched the 45' Flying Robin, so named tradition tells us because at the time of its launch a robin nesting in the bow took flight. Richard owned 51 shares, Peter 13. In 1872 the 45’ River Bride was slipped into the Little Passage, Peter owning all 64 shares; now Captain, Master Mariner. Upon the occasion of his son William Peter's marriage, he was given 32 shares of the Bride. Chronologically, the next schooner was the River Queen, described above. The last vessel owned by Captain Peter was the James Henry built in 1876 and purchased by him in 1892, three months after the loss of his beloved Queen. The River Queen was indeed his pride, and apparently the pride of his family as well, for a poem was written about her a few years after her demise. I first saw it, folded and faded, in the top drawer of my father's bureau along with a few other treasures of his past. What the poem lacks in literary merit it has in length, a fact I no longer resent since it provides us with a bit more of both history and legend, thus fact and fancy. The inaccuracies can be attributed to the youth and enthusiasm of the young authors, son Abraham and one James Plant. The spirit of competition was high among these mariners and many of the vessels mentioned were owned by brothers, cousins, and other relatives. Two, other than the subject of the piece, belonged in whole or part to Peter himself . On the 2nd of December, 1891, Captain Peter, his son William, nephew Michael and one Frank Smart sailed from Bras d'Or bound for Prince Edward Island to pick up 100 sheep at five dollars a head for a local farmer. They had travelled about forty miles toward the northern tip of Cape Breton when winds approaching gale force hit them from the southeast. The River Queen's skipper decided to put in to the shelter afforded by Aspy Bay, anchoring in the small cove at White Point. Some damage had been done to the rigging, but it could be easily repaired and the journey continued after the wind calmed. With a southeast wind they could ride out the storm. Suddenly and without warning the wind, now at gale force, swung around to the northwest and the little schooner was caught on a lee shore, sails furled and no time to gain the relatively greater safety of the open ocean. Her anchors dragged or were lost and she was driven up on the beach at White Point. As twilight approached it became apparent that the ship was lost and the crew scrambled ashore. In the gathering darkness they watched as the angry surf pounded Captain Peter's cherished schooner to pieces. The five hundred dollars stored under the bunk disappeared in the swirling flotsam which had been the splendid River Queen. She was the largest of some twenty ships lost that night near Cape North. Even as night closed in, the men began their fifty-mile walk back to Bras d’Or. As the sun rose the next morning the weary, hungry, and thirsty crew stopped at the farm of a Scottish widow for water. As Captain Peter stood at the kitchen pump quenching his thirst he observed a cow in the yard. The people were obviously poor and the captain had no money, but he asked if she might spare some milk. The woman turned to her daughter and said in Gaelic “Give them the milk the mouse drowned in.” Our grandfather, who spoke both French and English, also had a more than passing acquaintance with the Scottish tongue; he led his men down the road to the south. From a 1963 interview with nephew Michael age 93, an eye-witness account: "The storm came up suddenly, it surprised us and tore the ship to pieces. On the coast was a sandy beach and we were swept onto it. If the coast had been rocky we would have been lost. Yes, she left her bones on Cape North." According to this man, who sailed many a day with our grandfather, his captain and uncle was a good sailor and a jolly skipper, "a good man to be with on the sea." Captain Peter must have smiled that day. Over one-hundred Decembers have visited that lonely beach at White Point and the flash of the snow white canvas of the River Queen was not again to be seen on the sparkling waters of the Bras d’Or Lakes, but her history and legend live on. Eight years later her jaunty and able captain followed her in death and he lies in a grave on the very shores of the very lakes they both knew so well and sailed so proudly. As I write these lines I see a long ago image of my grandmother in her fine smelling kitchen, her hand mixing a cake in an old tan and brown bowl and listen, with thirsty ear, for her lilting voice singing: