Dulce et Decorum Est

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of gas-shells dropping softly behind.

Gas! Gas! Quick, boys! -- An ecstasy of fumbling,

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time;

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound'ring like a man in fire or lime. . .

Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams, before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil's sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues, --

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children desperate for some ardent glory,

The old lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

Wilfred Owen (1893-1918)

During World War One

Wilfred Owen was killed trying to lead his company of British infantrymen across an irrigation canal

in Belgium which was guarded by a German machine gun nest. Earlier in the war he had led men in

battle, had been seriously wounded and had spent a considerable period of time in hospital. Quite

frankly, long before his death, he had earned the right to speak about the nature of war and to feel

contempt for the romanticized versions of war's reality that one heard from politicians and that one

read on recruitment posters. Owen, however, was a poet in the traditional mold and he spoke in

poetic terms: he wanted to re-create a significant experience in his life and let that experience speak

for itself. His experience of war was roughly divided into equal parts of horror and anger, and "

Dulce et Decorum Est," his most famous poem, is more or less equally divided between his efforts

to re-create those same two emotions. Nearly a century later we can still "get the point."

During World War One

Wilfred Owen was killed trying to lead his company of British infantrymen across an irrigation canal

in Belgium which was guarded by a German machine gun nest. Earlier in the war he had led men in

battle, had been seriously wounded and had spent a considerable period of time in hospital. Quite

frankly, long before his death, he had earned the right to speak about the nature of war and to feel

contempt for the romanticized versions of war's reality that one heard from politicians and that one

read on recruitment posters. Owen, however, was a poet in the traditional mold and he spoke in

poetic terms: he wanted to re-create a significant experience in his life and let that experience speak

for itself. His experience of war was roughly divided into equal parts of horror and anger, and "

Dulce et Decorum Est," his most famous poem, is more or less equally divided between his efforts

to re-create those same two emotions. Nearly a century later we can still "get the point."

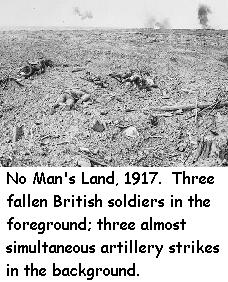

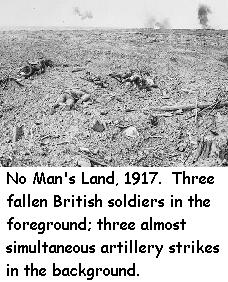

By 1916 the war was a stalemate --

long lines of trenches on both sides, separated by a nightmarish "no man's land"; and then came the

use of poison gases such as chlorine. It was horror on top of horror. Anyone who breathed in a

lungful of that green ("as under a green sea") gas was almost certainly doomed to a horrible death.

Inside the lungs, the gas would react with the moist tissues forming hydrochloric and other acids,

and these acids in turn would eat away at the delicate tissue of the lungs. Owen had seen such such

casualties before. Almost no one survived, and it was truly a horrible way to die.

By 1916 the war was a stalemate --

long lines of trenches on both sides, separated by a nightmarish "no man's land"; and then came the

use of poison gases such as chlorine. It was horror on top of horror. Anyone who breathed in a

lungful of that green ("as under a green sea") gas was almost certainly doomed to a horrible death.

Inside the lungs, the gas would react with the moist tissues forming hydrochloric and other acids,

and these acids in turn would eat away at the delicate tissue of the lungs. Owen had seen such such

casualties before. Almost no one survived, and it was truly a horrible way to die.

Owen's imagery graphically re-creates

his sense of horror. Some of the men have lost their boots, but their bare feet are so covered with

blood that they appear "blood-shod." The victim of the gas attack is described as "flound'ring like a

man in fire or lime," that is, flopping on the ground in agony like a fish out of water. The poor man

is "guttering, choking, drowning." All that can be done for the man is to put him on a cart and wheel

him off the battlefield:

Owen's imagery graphically re-creates

his sense of horror. Some of the men have lost their boots, but their bare feet are so covered with

blood that they appear "blood-shod." The victim of the gas attack is described as "flound'ring like a

man in fire or lime," that is, flopping on the ground in agony like a fish out of water. The poor man

is "guttering, choking, drowning." All that can be done for the man is to put him on a cart and wheel

him off the battlefield:

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs.

For the reader who visualizes the imagery of the poem, Owen is almost too graphic. One can see

too well --and hear too well -- the dying soldier strangling on his own blood.

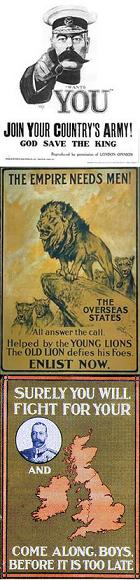

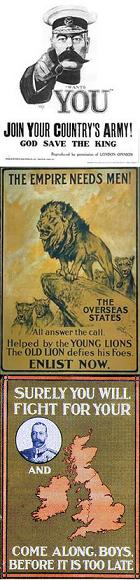

Inevitably the horror leads to anger

against those who have painted the war in the heroic and romanticized terms of recruitment posters.

Owen has seen too much of the horror of war to be impressed by the rhetoric and romantic imagery

of the military recruiters who tell the youngsters back home -- those "children ardent for some

desperate glory" -- the same "old lie" that has been told since at least the time of the Romans:

Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori. (It is sweet and fitting to die for one's country.) The

bitterness of tone when Owen calls such a person "my friend" seems clear; it is the tone of outrage

and anger provoked by having seen so much horror in the war:

Inevitably the horror leads to anger

against those who have painted the war in the heroic and romanticized terms of recruitment posters.

Owen has seen too much of the horror of war to be impressed by the rhetoric and romantic imagery

of the military recruiters who tell the youngsters back home -- those "children ardent for some

desperate glory" -- the same "old lie" that has been told since at least the time of the Romans:

Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori. (It is sweet and fitting to die for one's country.) The

bitterness of tone when Owen calls such a person "my friend" seems clear; it is the tone of outrage

and anger provoked by having seen so much horror in the war:

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs. . .

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

The reader can feel Owen's sense of anger just as keenly as his sense of horror.

Although the Latin phrase from

ancient Rome suggests that those who lead us into wars and who manage the affairs of war have

always glorified war and have always encouraged the young to view war as a great heroic adventure,

the horror and anger in Owen's poem are palpable and real. We can imagine the "smothering"

nightmares of the speaker who was helpless to save his comrade, and we can sympathize with the

poet's contempt for recruitment poster rhetoric. Nearly ninety years have passed since the events

depicted in the poem, but Owen brings it all back to mind as if what happened in the poem was a

story in the daily news.

Although the Latin phrase from

ancient Rome suggests that those who lead us into wars and who manage the affairs of war have

always glorified war and have always encouraged the young to view war as a great heroic adventure,

the horror and anger in Owen's poem are palpable and real. We can imagine the "smothering"

nightmares of the speaker who was helpless to save his comrade, and we can sympathize with the

poet's contempt for recruitment poster rhetoric. Nearly ninety years have passed since the events

depicted in the poem, but Owen brings it all back to mind as if what happened in the poem was a

story in the daily news.

There are no absolute truths about war. Speak well of

the courage and sacrifice of the soldier, and someone will charge you with glorifying war; speak

angrily of the folly, the horrors, the terrors and waste of war, and someone else will accuse you of

cowardice; speak convincingly against the necessity of whatever war your generation is fighting, and

still others will accuse you of treason; speak convincingly of the absolute necessity of your

generation's war; and voices will scream that you are a war-monger or an imperialist; speak sadly of

your friends who died, and there are some who will call you weak; speak accurately of war's actual

costs in blood and treasure, and you will certainly be called insensitive and cold-blooded; choose to see your enemy as demonic, and you are called simplistic and naive; choose to

see some right upon your enemy's side, and you could end up before a firing squad. And -- God

help us! -- tell stirring tales of battles and victories over a satanic opponent, and the many will listen

attentively and praise your tales. Robert E. Lee once said, "It is well war is so terrible; else we should grow too fond of it." Clearly he was right! -- This is how I remember my father's standard speech about war. He was a young man during World War Two.

Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori. An excellent translation of this Latin phrase is: "It is beautiful and fitting to die for your country."

"Men! Your job is not to die for your country! Your job is to make some other poor son-of-a-bitch die for his country." -- General George S. Patton, United States Army General during World War Two

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

During World War One

Wilfred Owen was killed trying to lead his company of British infantrymen across an irrigation canal

in Belgium which was guarded by a German machine gun nest. Earlier in the war he had led men in

battle, had been seriously wounded and had spent a considerable period of time in hospital. Quite

frankly, long before his death, he had earned the right to speak about the nature of war and to feel

contempt for the romanticized versions of war's reality that one heard from politicians and that one

read on recruitment posters. Owen, however, was a poet in the traditional mold and he spoke in

poetic terms: he wanted to re-create a significant experience in his life and let that experience speak

for itself. His experience of war was roughly divided into equal parts of horror and anger, and "

Dulce et Decorum Est," his most famous poem, is more or less equally divided between his efforts

to re-create those same two emotions. Nearly a century later we can still "get the point."

During World War One

Wilfred Owen was killed trying to lead his company of British infantrymen across an irrigation canal

in Belgium which was guarded by a German machine gun nest. Earlier in the war he had led men in

battle, had been seriously wounded and had spent a considerable period of time in hospital. Quite

frankly, long before his death, he had earned the right to speak about the nature of war and to feel

contempt for the romanticized versions of war's reality that one heard from politicians and that one

read on recruitment posters. Owen, however, was a poet in the traditional mold and he spoke in

poetic terms: he wanted to re-create a significant experience in his life and let that experience speak

for itself. His experience of war was roughly divided into equal parts of horror and anger, and "

Dulce et Decorum Est," his most famous poem, is more or less equally divided between his efforts

to re-create those same two emotions. Nearly a century later we can still "get the point."