There was such speed in her little body,

And such lightness in her footfall,

It is no wonder that her brown study

Astonishes us all.

Her wars were bruited in our high window.

We looked among orchard trees and beyond,

Where she took arms against her shadow,

Or harried unto the pond

The lazy geese, like a snow cloud

Dripping their snow on the green grass,

Tricking and stopping, sleepy and proud,

Who cried in goose, Alas,

For the tireless heart within the little

Lady with rod that made them rise

From their noon apple-dreams, and scuttle

Goose-fashion under the skies!

But now go the bells, and we are ready;

In one house we are sternly stopped

To say we are vexed at her brown study,

Lying so primly propped.

John Crowe Ransom, 1924

Shock and Resentment in Ransom's "Bells for John Whiteside's Daughter"

John Crowe Ransom is perhaps best known for "Bells for John Whiteside's Daughter," his frequently reprinted 1924 poem about the death of a very young girl. To be more accurate, "Bells" is less about the little girl's death itself than it is about the reactions of the speaker to that sudden death. The language of the first and last stanzas of the poem as well as the use of first person plural pronouns throughout the poem clearly emphasizes the speaker's shock and resentment that such a lively and vivacious "little lady" could be so suddenly taken out of the world. To put it another way, an important part of the experience presented in the poem is the sense that something is very wrong with a world in which such things are permitted to happen.

It is obvious that the opening stanza of the poem pointedly emphasizes the speaker's shocked reaction to the girl's death:

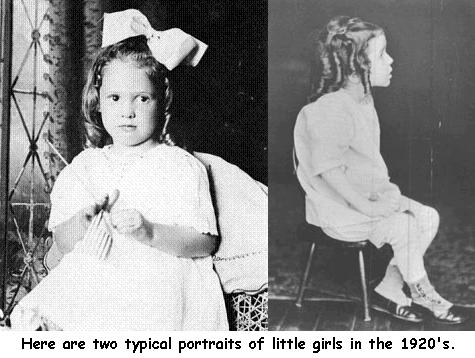

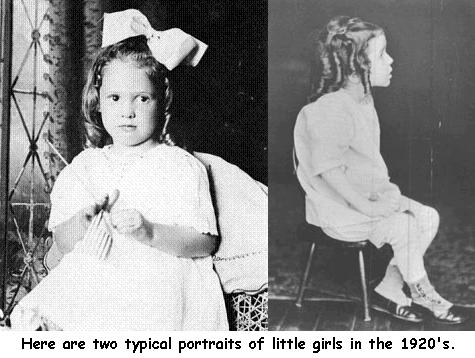

There was such speed in her little body,The speaker is amazed, surprised, and caught off guard by the girl's sudden passing; he is almost thunderstruck by the contrast between the speedy little girl and the "brown study" into which she has fallen. The root meaning of astonished is "thunderstruck"; and brown study -- a euphemism for death which means "a morose, serious, or heavy mood" -- certainly captures the shocking contrast between the light-hearted living child and the "primly propped" corpse laid out in the old-fashioned home burial style of the early 20th Century. Just days ago the child was chasing geese with a stick; today she is in a coffin in the parlor of her wealthy father's home. All the neighbors -- including the speaker -- are gathered at Whiteside's home, ready to take the child's body to the churchyard for burial. The shock and distress of the community is very evident.

And such lightness in her footfall,

It is no wonder that her brown study

Astonishes us all.

It is also obvious that the last stanza of the poem emphasizes the speaker's troubled reaction to abrupt and sudden death of the child:

But now go the bells, and we are ready;Vexed, of course, means "troubled, irritated, or even angry"; and, after reading the marvelous three stanza description of the little girl's "wars" against the geese, it does indeed seem vexing that such an innocent, charming and amusing child has been taken by death.

In one house we are sternly stopped

To say we are vexed at her brown study,

Lying so primly propped.

There is, therefore, a very clear emphasis on the shocked and angry reactions of the speaker. This is especially true because the use of "we," "us," and "our" throughout the poem makes the speaker into a sort of spokesman for the community at large. Indeed, the speaker is speaking for all of us: "we are vexed," "we are sternly stopped," and "her brown study astonishes us all." We may not be suffering the profound anguish of the little girl's parents, but we are all shocked and resentful every time the death of such a child as this occurs.

As the poem ends, the church bells are tolling. It is time for the procession to the church, for the religious services which traditionally attempt to offer consolation for such loss. And it is exactly at this moment that the spokesman/speaker of the poem points out that "we are sternly stopped" and that "we are vexed." In short, even as we are ready to go to the church, we are still shocked and resentful; yet if we are resentful, we must have a target for our resentment. Ransom is dignified and restrained in tone, but a very important part of his poem implies the question: What kind of God allows the death of such children?