"Chief" William John Compton

by

Ray Hodgson, San Pedro, California

"Chief" William John Compton was born in Michigan in 1862 and died suddedy on Monday, May 16, 1938, of a heart attack. He was adopted by a Sioux Indian tribe and spent his early boyhood days roaming the plains of Nebraska and the Dakotas, where he learned, first hand, the use of the bow he loved so well. Ho came to California 28 years ago and has devoted much of his time to lecturing on archery. He lectured at San Francisco and at Chaffee Junior College, Ontario. He was an outstanding instructor in archery and was a life member of the San Pedro Archery Club. He was the last surviving member of the three adventurous bow men, spoken of in Doc Pope's book as Chief and Doc and Art.

The Story of Ishi, the Yana Indian

by

W. J. "CHIEF" COMPTON

Along in the nineteen hundreds stockmen were puzzled by the disappearance of grain from cabins in the mountains of Tehama county, California, placed there for saddle horses used for rounding up stock in the vicinity of Deer Creek.

The thing that puzzled the cowboys the most was that the thieves never took any of the food brought to the cabins for their own use, although they often found the canned goods and other food scattered all around the place; but the rolled barley for the saddle horses was always taken whenever a cabin was broken into.

The shecpmen suffered loss at the same time by having

sheep die suddenly.

In making a post mortem examination they discovered obsidian arrow heads

in the dead sheep. The ranchers were sure, upon this discovery, that the

maurauding had been done by an Indian, or Indians. But there were no wild

Indians in that part of the country, or anywhere else, that they knew of.

For years this sort of thing had been going on when the ranchers

in and around Deer Creek decided to put in a big ditch for irrigation purposes,

the water was to be taken out of the upper reaches of Deer Creek. In the

course of time the surveyors were on the job running the line through the

chaparral where the ditch was to go and it so happened one evening, at

the close of the day's work, that four or five of the crew started for

their camp which was on the opposite side of Deer Creek.

For years this sort of thing had been going on when the ranchers

in and around Deer Creek decided to put in a big ditch for irrigation purposes,

the water was to be taken out of the upper reaches of Deer Creek. In the

course of time the surveyors were on the job running the line through the

chaparral where the ditch was to go and it so happened one evening, at

the close of the day's work, that four or five of the crew started for

their camp which was on the opposite side of Deer Creek.

When they arrived at the creek bank they discovered that the creek was unusually high, and, as they had approached it at a point that was strange to them, they were discussing the feasibility of the particular spot for a crossing. They were on horses and as they entered the water the splashing and clattering of their horses was drowned by the roaring of the high waters of the creek.

As they followed the riffle where the water was the shallowest, they were going on an angle and had just passed an elbow in the creek bank which had obscured their vision as to what was immediately beyond this projection. The riffle led them within a few feet of this shoulder. When they advanced into the water so thcy could see what was behind the turn in the bank, they saw a naked Indian with a spear in his hand watching for salmon trout. He discovered them at the same instant and he ran at them, salmon spear poised for a throw.

The horsemen scattered and scrambled across the creek anywhere. They rode into camp and told the others about seeing the wild Indian, but, as the as the days ran into weeks and no Indian was seen again, the camp commenced to doubt the story of those who claimed to have seen a naked Indian fishing with a salmon spear.

About one year after they found him fishing in the creek, they encountered him again in a most peculiar manner. Two men from this same surveying crew, one of whom was with the party when they found him the first time, were riding along on horses when the one who had been present at the first encounter suddenly exclaimed that they were in the vicinity of the spot where they discovered the wild Indian. His companion greeted the information with a laugh and said. "You fellows must have had some kind of a pipe dream about that Indian as no one except you fellows has ever seen him. Where is he now?"

Just as he asked the question an arrow zipped through the interrogator's hat. There were no more questions regarding his whereabouts. They were both of the same mind instantly: that without doubt they had found out where he was-for the moment at least. Having decided this very quickly and positively, they departed from that vicinity, pronto, in a cloud of dust, headed for camp.

When they told the story, the hunt was on to find the bowman

that had loosed the almost fatal shaft. The whole crew turned out for the

hunt as they were all convinced that there were wild Indians around and

uncomfortably close by. So they started to search all the big thick patches

of chaparral, and they found the camp in the thickest of this growth. Just

a brush wickiup, the corner posts of which were scarcely larger than a

man's thumb. The roof was brush with bark laid on top. There was

also a deep wide hole in the ground that they would fill with snow in the

winter to furnish water for the camp.

When they told the story, the hunt was on to find the bowman

that had loosed the almost fatal shaft. The whole crew turned out for the

hunt as they were all convinced that there were wild Indians around and

uncomfortably close by. So they started to search all the big thick patches

of chaparral, and they found the camp in the thickest of this growth. Just

a brush wickiup, the corner posts of which were scarcely larger than a

man's thumb. The roof was brush with bark laid on top. There was

also a deep wide hole in the ground that they would fill with snow in the

winter to furnish water for the camp.

At the time of discovery by the ditch crew only a very old woman was at home and she was in bed sick. They knew that this old woman was not the person who had sped the arrow through the hat of one of their number a few hours before, so they knew that there was at least one bowman missing; but could not know how many more. After picking up everything in sight that was loose at both ends they departed. The next day they returned, their numbers greatly augmented. But, on this second visit, they found the old woman gone. The others, they knew, had returned and carried her away.

When the souvenir collectors fully realized that there was nothing between them and the complete destruction of the camp, joy oozed from every pore as they proceeded to demolish everything and tie in bundles the fragments for easy transportation to their homes. Where the Indians had gone they could not even guess at in their departure they left no trail.

Several months after this the butchers in a slaughter house near Oroville heard a dog barking furiously in the yard outside the buildling. Going outside to investigate they found a naked Indian. When asked who he was and what he wanted, thev discovered that he did not understand what they were saying. They sent for some Digger Indians who they knew to do the talking but with no better results. They then tried out the linguistic powers of a Pititc but it also failed. Something had to be done if they were to find out anything about their strange visitor.

All this time the Indian thought they were planning to kill him. At this juncture some one thought of phoning the University of California at Berkley to see if that institution could help them out of their dilemma. The university sent a Mr. Waterman, a student of dead languages.

Well, in due time, Waterman arrived, and just before the Yana tongue became a dead one as the Indian by this time was all but scared to death. Waterman tried out different Indian languages but this wild Indian knew none of them. Then he thought to try the Yana tongue on him. That brought results quickly. There was a small pine table in the room. Waterman placed his hand on this and said the word for pine in Yana. The word was "sawe enie." Immediately, Ishi came alive and wanted to know of Waterman if he was a Yana, or Yahe, as he called himself. Waterman told him that he was. In less than three weeks time, Waterman apparently was speaking Ishi's mother tongue fluently.

Arrangenents were made with the University of California and Affiliated Colleges to bring Ishi to the Affiliated Colleges at San Francisco. It was here that Dr. Saxton Pope, Arthur Young, and I became acquainted with him. We found him to be a man right from the stone age. In spite of the handicap we were all in agreement that he, a savage, was the gentlest human being either of us had ever met.

We hunted game with him and he was always the best of companion. He was with us over five years and in that length of time we never saw him out of humor. When he hunted small game he would make calls to lure them within shooting distance that were quite effective at times. He would imitate the cry of a rabbit in distress which, he said, would bring a wild cat or lynx to him if there were one within hearing distance.

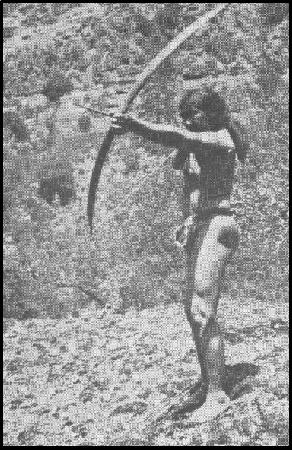

He shot well up to forty yards. The how he used was short

and would pull about fifty-five pounds. He shot the same bow for hunting

and target. At target he was a poor shot. It was something foreign to his

life time practice with the bow. His fletching job was good but he preferred

the tail feathers of the turkey to the quill feathers. Why he had this

preference we never found out. Probably some superstition. He made his

arrow heads of obsidian- the workmanship was superb, perfect in form and

extremely sharp. They would penetrate flesh as easily as the sharpest steel.

In making these heads, he used a piece of buck- horn about five inches

long, tapered down to about one-sixteenth of an inch across, and square

in form. He held the obsidian in his hand and pressed it against the small

squared end of the buckhorn and twisted. In this crude manner he chipped

away the excess material, producing the most perfect stone or obsidian

arrow heads I have ever seen. His bow strings were made of sinew.

His bow was made of mountain juniper if he had it. If not he would condescend to use yew. He said yew wood was only fit for the use of women. We could understand his attitude towards women. his knowledge of women being gained through association with his aunt and his sister, his uncle teaching him all the old superstitions regarding the weaker sex. But how he got the idea that juniper was better bow wood than yew we never found out. Some more superstition, I suppose, he said to us, "Never allow a woman to touch your bow, as it will not shoot well if they do."

His uncle told him that before the white man came game was very plentiful. They hunted in large parties of twenty to fifty or more. A portion took a stand, well concealed, while the remainder of the party drove the game within shooting distance of those on stand. Of course, all this was told him by his uncle, as there were only his uncle, aunt, and sister of the Yana tribe living since Ishi was four years old. When visiting in Dr. Pope's home he would act as though he never saw Mrs. Pope at all; the idea being that it was very impolite for a man to notice another man's woman.

The thing that astonished Ishi the most of all the astonishing things he saw when he came to San Francisco was the disapearance of a window shade when it rolled up. That completely stunned him. Another thing that excited him out of his natural calm, also pleased him greatly, was to see himself in pictures. When he showed up at the slaughterhouse in Oroville, his hair had been burned off close to the scalp as a sign of mourning. They took several pictures of him at this time wearing short hair and always when be would see himself in one of these pictures it would please him beyond words.

Ishi enjoyed the best of health to within one year of his death, when he commenced to show signs of tuber culosis. Everything was done for him that human hands and minds could do; but nothing could be done to arrest the disease, and we bade farewell to Ishi on June the 16th, 1916. His words were "I go, you stay," and thus passed on one of the most noble of the redmen. A true friend and a noble character. Everyone loved him that knew him.

We-Young, Pope and I, saw to it it that he was left alone by the religious sects, and that he was allowed to die in the faith of his people. We buried him in the Italian cemetery in San Francisco-the last of the Yana Indians.