| INTRODUCTION | LIVER |

| BONEMARROW | PANCREAS |

| KIDNEY | HEART & LUNG |

HEART TRANSPLANTATION MAIN INDICATION FOR HEART TRANSPLANTATION:Advanced terminal cardiac disease classified as NewYork Heart Association (NYHA) 4, with no alternative conventional medical or surgical treatment, and with a mortality rate higher than 90% per year if transplatation is not carried out is an indication for heart transplantation.Most cases referred for transplantation have an ischaemic or dilated cardiomyopathy.Rarer causes include post-viral and hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy.The patient needs careful evaluation and proper pre-operative assessment to determine the suitability for transplantation and counselling to prepare for the demands of life after transplantation.Younger patients tend to benefit more.In the recent years the indication for transplantation have broadened.Unfortunately, the limiting factor on the number of transplantations performed per year is the availability of donor hearts.

ABSOLUTE CONTRA-INDICATIONS TO TRANSPLANTATION:

RELATIVE CONTRA-INDICATIONS TO TRANSPLANTATION:

Donor selection is critically important if early post-operative problems are to be avoided.Potential donors will be certified as brain dead if two separate brainstem function tests show no activity.Most donors have had head injuries or an intracerebral haemorrhage.Injuries to other organs may be present, but if the heart shows no evidence of injury then it may be used.Haemodynamic instability can occur at any time in these patients, and skilled intervention with judicious use of inotropes, ventilation and diuretics may be required to keep the patient stable until the organs are harvested.

IDEAL CRITERIA FOR DONORS:

DONOR OPERATION:

The donor operation is usually performed in conjunction with other transplant teams.The liver and kidneys require some preliminary dissection before the removal of the heart.The heart is exposed by a median sternotomy and the cavae are dissected from the pericardial reflections to expose more of their length.Heparin is given and the aorta cannulated with a perfusion catheter.The aorta is clamped and the inferior vena cava divided to allow venous blood to escape into the chest.Cold cardioplegic solution is infused under pressure into the aortic root and the heart arrests in diastole.A pulmonary vein is then divided to allow blood in the left atrium to escape. Once the cardioplegic solution is infused, the pulmonary veins are divided followed by the pulmonary artery.The aorta is then divided just below the crossclamp, leaving only the superior vena cava to be divided.This is divided as high as possible to avoid damage to the sino-atrial node.Care should be taken that all central venous cannulas are withdrawn to avoid possible embolism in the donor heart.The heart is then stored in cardioplegic solution and transported in ice to the recipient hospital.

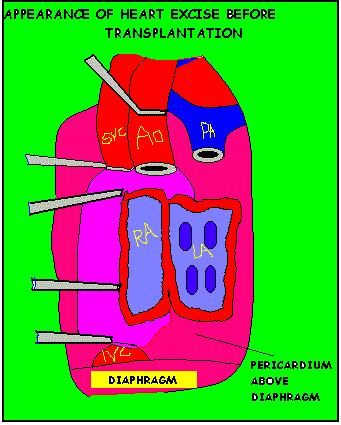

THE RECIPIENT OPERATION:Once it is clear that the donor heart is satisfactory then the recipient operation is started.The heart is approached through a median sternotomy and heparin is given intravenously.The cavae are cannulated separately and the aorta is cannulated just proximal to the innominate artery.Cardiopulmonary bypass is not started until the donor heart is in the operating room.The recipient heart is excised leaving a generous cuff of atria and interatrial septum.The donor heart is trimmed appropriately and suturing begins with the left atria, the right atria, the pulmonary artery and finally the aorta.The heart is then de-aired and the crossclamp released.Ventricular activity usually starts spontaneously but occasionally temporary pacing is required.The heart is allowed to beat on bypass until rewarming is complete and hemostasis is achieved.Ventilation is commenced and cardiopulmonary bypass is slowly weaned until the donor heart is supporting the circulation.

POST-OPERATIVE CARE:In common with all forms of allogenic transplantation, the normal host response is to mount an immune response to the donor organ.To combat this problem, regimens of immunosuppressive therapy have been developed.Intravenous methylprednisolone and azathioprine are given at the time of operation and these are converted to the oral forms once the patient is able to tolerate oral or nasogastric fluids.Cyclosporin A is added if the renal function is satisfactory.Cyclosporin A is nephrotoxic and regular trough levels are required to avoid excessive toxicity.Treatment with azathioprine can result in liver dyscrasias and neutropenia.The incidence of rejection is greatest in the first year post-transplantation.The only reliable way of monitoring the presence or absence of rejection is by endo-myocardial biopsy.This is an invasive procedure requiring cannulation of a major vein and taking small biopsies of the ventricular septum from the rigth ventricle.The presence of a lymphocytic infiltrate suggests rejection and myocyte necrosis implies severe rejection.A pulse of intravenous steroids is usually given as first-line treatment but other therapies include anti-lymphocyte globulin and the monoclonal antibody preparation OKT3.Most rejection episodes resolve with treatment but occsionally the rejection is refractory to treatment and the allograft fails.Another important cause of morbidity and mortality in these patients is infections.Immunosuppression lowers the host's resistance to infection and opportunist infections may occur.The most common site for infection is the chest.Antibiotics should not be commenced until a full infection screen (throat swabs, midstream urine, sputum and venous blood cultures) has been taken.Viral, protozoal and fungal infections may also occur.Late complications include accelerated graft vascular disease and systemic malignancy.

RESULTS:The perioperative mortality rate is about 10% but patients surviving to leave hospital may have a 90% 1-year survival.This falls to 70% at 5 yrs and 60% at 10 yrs.Patients surviving more than 1 yr usually have a good exercise capacity and are able to return to work.

FUTURE PROSPECTS:Heart transplantation is limited by donor availability.Increasing donor pool by widening donor criteria and increasing public awareness have helped, but demands exceed supply.The use of xenografts is one possibility but ethical, logistic and rejection problems mean that this prospect is a long way off.Artificial hearts have a role to play in supporting the circulation until a heart becomes available for transplantation but they do not seem practical for long term use.

LUNG TRANSPLANTATION Lung transplantation for end-stage lung disease has been a therapeutic option since the 1980's.Several transplant options are available for carefully selected patients:

PROSPECTSIn late 1995, the Registry of International society for Heart and Lung transplant reported a cumulative total of 1708 heart-lung transplants.Unilateral and bilateral lung transplants both have 1-year survivals of 67% and 3-year survivals of about 50%. Heart-Lung recipient survivals are 56% at 1-year and less than 20% at 10-years. Among the unilateral transplant recipients, disease sub-categories appear to affect early survival, with emphysema patients enjoying the best 1-year survival, approximately 75%, and pulmonary fibrosis patients experiencing the worst, at just over 60%.Data on survival of living-related lobar transplants are not yet available.

INDICATIONSEmphysema, either smoking induced or secondary to alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, has been the single largest indication for lung transplantation.This disease accounts for almost 60% of all single lung-transplants, more than 30% of all bilateral lung-transplants, and 9% of heart-lung transplants.Other major indications for single lung transplantation include: Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, primary pulmonary hypertension, and a variety of other rarer diseases.The major diagnoses among heart lung recipients are primary and secondary pulmonary hypertension (60% of recipients) and cystic fibrosis (15% of recipients). With the widespread use of isolated unilateral and bilateral transplants, the indications for heart-lung transplantation have become very circumscribed, so that most of these patients now have either concomitant left ventricular disease and end-stage lung disease or irreparable congenital heart disease with Eisenmenger's syndrome. Patients recieving living related lobar donations have been either childern or young adults, and most have suffered from cystic fibrosis.In majority of living related donations, the recipients has recieved two lower lobes- one transplanted on the right, one on the left- taken from two separate donors.

RECIPIENT SELECTIONBecause donor lungs are the scarcest of the common solid organs transplanted, patients with end-stage lung disease undergo extensive evaluation to select the best potential candidates.In general, good candidates have severe, progressive lung disease with a projected life span of less than 2 yrs.They must not be active smokers; the length of time of smoking abstinence required prior to consideration for transplant varies among programs but is usually atleast 6 months.In addition they should have no other systemic disease with significant end-organ damage that would impact on the post-transplant outcome.This includes significant coronary artery disease, renal insufficiency, hepatic disease, severe osteoporosis, or significant neurologic impairment.Other comorbid conditions such as previous malignancy, systemic illnesses, and chronic unresolved infections outside the lung may also preclude lung transplant.Considerations that are thought, though not proven, to enhance outcomes include ambulatory status, adequate nutrition, demonstrated motivation/compliance, and psychological stability.In the early years of lung transplantation, patients with prior thoracic surgery were felt to have an unacceptably high risk of post-operative haemorrhage, and patients on glucocorticoids were felt to be at high risk of anastomotic healing complications.With improvements in surgical technique and refinements in early post-operative immunosuppressive management, potential candidates are now rarely rejected for either of these reasons provided the surgery has not been multiple or extensive and the glucocorticoid dose is less than 20 mg/d.Many programs use age cutoffs between 55 and 65 years in selecting potential recipients.While these age limits are arbitrary, international registry data confirm that recipients older than age 60 have poorer survivals. It is often difficult in the case of specific pulmonary diseases to determine when patients are within the transplant "window" - that is, have disease advanced enough to fit within the category of "end-stage" yet are not so ill that they will not survive the rigorous transplant operation or die during the long pre-transplant waiting period.However, experience in evaluating patients and published longitudinal data has identified useful criteria for identifying appropriate candidates (FIG I).Emphysema patients and patients with Eisenmenger's physiology are most difficult groups in which to predict life expectancy; patients with severe limitations even in activities of daily living may still have survivals at 3 to 5 years that are comparable to patients who have undergone transplantation.Thus, in many centres, the selection of emphysema candidates for transplantation involves not only projected survivals but also quality-of-life issues.Selecting patients with Eisenmenger's physiology is even more difficult.Survivals of patients waiting for atleast a year for transplantation have been as good or better than 1-year survival of similar transplanted patients.Clearly, this group of patients does not behave in the same way as primary pulmonary hypertensive patients, and more specific selection criteria are needed. There are regional variations in waiting times for transplantation, and minor differences in the listing criteria for individual centres will reflect anticipated length of wait. SELECTION OF TRANSPLANT PROCEDUREThe only diseases that currently mandate a specific procedure are:

In essentially all other diseases, single-lung transplantation can be performed with acceptable early and midterm results.Bilateral lung transplantation may be performed if there is difficulty in post-operative management, especially in pulmonary hypertension, significant bullous disease in emphysema, young age, surgeon preference, or as dictated by individual patient considerations.It is not yet known whether unilateral and bilateral lung transplant recipients will have similar long-term survivals and functional outcomes.However, most transplant physicians agree that maximizing donor organ resource by performing unilateral transplants whenever possible is currently optimum policy.

FUNCTIONAL OUTCOMESA variety of tests have been used to evaluate lung transplant outcomes including arterial blood gases, perfusion scans, pulmonary function studies, compliance measurements, and exercise studies.Arterial blood gases in both unilateral and bilateral lung recipients improve markedly by 3 months posttransplant.In both types of recipients, PCo2 normalizes; in bilateral transplants, PO2 also normalizes.Unilateral transplant recipients may continue to have mild hypoxemia but rarely require supplemental oxygen.Perfusion studies in unilateral transplant recipients have shown that by 3 months posttransplant the donor lung recieves approximately 80% of the perfusion; this may be higher if the underlying diagnosis is pulmonary hypertension.Pulmonary function studies in patients recieving either one or two lungs reach their maximum by between 3 and 12 months post-operatively.Unilateral lung recipients who had a preoperative diagnosis of parenchymal lung disease reach 60 to 65% of the maximum predicted values of FVC and FEV1.Bilateral lung recipients can reach normal predicted values but often have mild restriction.A moderate amount of restriction has been reported in heart-lung recipients, but this may reflect a policy of selecting relatively small donor lungs.Nongraded exercise tolerance (6 min walk test) is similar for all lung recipient groups and ranges between 600 and 700m per 6 min.Bilateral lung transplant recipients perform better on graded exercise studies (eg- modified Bruce protocol) than do unilateral transplant patients, but both groups achieve only 40 to 60% of predicted maximums.The reason for this exercise limitation, particularly in bilateral lung transplant recipients, is not clear.In most cases, the exercise limitation does not impact upon normal daily living, and patients report significant improvement in quality of life following lung transplantation.For some years the transplantation of either a single lung or both lungs separate from the heart was fraught with difficulty, mainly because of poor healing of the devascularized bronchial/tracheal anastomosis.Recently this has been corrected by employing either an omental or vascularized intercostal muscle wrap technique.Alternatively micro-vascular anastomosis of the bronchial arteries to the internal mammary artery may be performed.The rest of the procedure entails the removal of the lung, clamping the appropriate vessels and re-anastomosis using standard vascular techniques.'Cardio-pulmonary bypass' may only be necessary for some cases of single lung transplantation.In the case of double lung transplantation, bypass is obviously required, and again a cuff of atrium is left attached to the lungs to allow easy anastomosis to the recipient left atrium.However, partly for this reason,en bloc double lung transplantation is now rarely performed, having been replaced by bilateral single lung transplantation at the one operation so that cardio-pulmonary bypass may be avoided; in addition, there are fewer air-way anastomotic problems.Patient and graft survival remains inferior to cardiac transplantation, about 50% of patients surviving the first year.However, advances in lung preservation and better patient selection are expected to improve these figures in future.

POST-TRANSPLANTATION MANAGEMENT ISSUESACUTE REJECTIONMore than 75 percent of lung transplant recipients will experience atleast one episode of acute rejection.Most episodes occur within the first 3 months, but acute rejection can occur upto several years posttransplant.Patients usually present primarily with dyspnoea but can also have cough, fever, and malaise.Findings include rales, hypoxemia, deteriorating FVC and FEV1, and as the process advances, perihilar infiltrates on the chest x-ray and leukocytosis.Often, however, if the patient presents early, the x-ray is unremarkable.The diagnosis is best made by transbronchial biopsy, which is sensitive and specific, and, especially in the early post-transplant period, it helps to rule out infections such as CMV (cytomegalovirus), which has a similar presentation.Most episodes respond to high-dose intravenous methyl-prednisolone.Upto 20% of asymptomatic patients will have atleast one episode of acute rejection on surveillance transbronchial biopsy during the first two years post-transplant.It is not clear whether asymptomatic rejection requires therapy, since its impact on outcome is unknown.This uncertainty has led to varying practices among institutions concerning the use of surveillance bronchoscopy, which can be quite expensive.

BRONCHIOLITIS OBLITERANSBronchiolitis obliterans is the primary manifestation of chronic rejection in lung transplants.Some degree of bronchiolitis obliterans occurs in upto 50% of patients who survive atleast 5 years and is the cause of death in more than one-fourth of long-term survivors.The only factors that clearly have been shown to predispose patients to the development of bronchiolitis obliterans are the number and severity of acute rejection episodes.The onset, usually 6 months post-transplant, is often subacute, with gradual onset of shortness of breath, viral type symptoms, or malaise.It can be asymptomatic and detected incidentally by the insiduous development of airflow obstruction on pulmonary function testing.Histology by transbronchial biopsy can confirm the diagnosis but is generally not very sensitive;therefore, a typical clinical picture with airflow obstruction in the absence of any other etiology is now considered sufficient to document bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome.Patients developing this syndrome may have rapidly progressive loss of lung function, but more often they have a gradual progressive fall in FEV1 over months or years or have a sudden drop in FEV1 with subsequent stabilization.Unfortunately treatment, which is with augmented immunosuppression, is rarely successful in reversing obstructive changes but may slow the loss of function for variable periods of time.

INFECTIONSInfections are second only to rejection as a cause of morbidity in the lung transplant population and are the most common cause of mortality, accounting for a third of all deaths occuring both during and after the first 3 months post-operatively.Infections are more common in the lung transplant recipient than in any other solid organ recipient.The transplanted lung may be uniquely vulnerable to infection because of imparied muco-ciliary clearance, loss of cough reflex, and other poorly defined local factors.In addition, the donor lungs are often colonized with organisms that are transmitted directly to the recipient.SOme series have reported that atleast 60% of lung recipients experience an infectious episode requiring treatment.Most of the infections are pulmonary, either pneumonia or bronchitis, and most are bacterial or viral, though recently fungal infections, especially with Aspergillus, have been increasingly reported.Bacterial infections are caused most often by gram-negative bacilli or staphylococcal organisms.CMV infection with pneumonitis, as with all solid organ transplants, remains a significant threat, especially in the highest risk group in which the donor is CMV serology-positive and the recipient is CMV serology-negative.Elaborate systems of antimicrobial prophylaxis, employed now by most centres, along with increased experience of transplant physicians appear to have been effective in reducing the morbidity from viral, bacterial and pneumocystitis carinii organisms.Antifungal prophylaxis is also sometimes used since invasive fungal infections have a high mortality rate.The two particularly high-risk periods for infection are in the first 3-months postoperatively and late after transplant if the patient develops bronchiolitis obliterans.In the early post-transplant period, it may be very difficult to distinguish infection from rejection, and bronchoscopy with transbronchial biopsies and appropriate cultures are often required to make a diagnosis.Late after transplant, many patients with bronchiolitis obliterans have an increased risk of bacterial infections.These patients often develop bronchiectasis, become chronically colonized with Pseudomonas organisms, and experience repeated episodes of Pseudomonas bronchitis or pneumonia.

AIR-WAY COMPLICATIONSCareful examination of post-transplant airways in the first few post-operative weeks reveals many small dehiscences, but approximately 15% of lung transplant recipients experience airway stenosis requiring either dilatation, laser resection, or stenting.Other airway problems include impairment of the mucociliary clearance and the development of bronchial hyperreactivity by many patients.These changes may be due to denervation, ischaemia, and low-grade chronic airway inflammation.IMMUNO-SUPPRESSIVE COMPLICATIONSThese are common in lung transplant recipients.Nephrotoxicity, hypertension, and hyperlipidaemia occur in the majority of patients treated with current immunosuppressive regimens: however, fewer than 5% develop renal failure requiring dialysis or renal transplant.Neurotoxicity, including strokes, coma, severe headaches, and seizures, occurs in upto 20% of patients, as does osteoporosis with vertebral compressions or other fractures.Lymphoproliferative disorders occur within the first year in approximately 5% of lung transplant recipients;many of these appear to be related to infection with the Epstein-Barr virus.Late after transplant, there is an increased incidence of many types of carcinoma and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.

RECURRENCE OF UNDERLYING DISEASERecently, several episodes of recurrence of the underlying disease have been reported in patients undergoing lung transplantation.Several transplant centres have reported the recurrence of sarcoidosis in transplanted lungs, usually as a histologic diagnosis and not clinically apparent.There have also been case reports of recurrent lymphangioleiomyomatosis, giant cell interstitial pneumonitis, and panbronchiolitis.Presumably, alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency-related emphysema will recur in susceptible patients if they survive long enough, but this has not yet been reported; alpha-1-antitrypsin replacement therapy is not universally employed in these patients.It must be made clear to all lung transplant recipients that permanent abstinence from smoking is necessary.The abnormal electric potentials characteristic of cystic fibrosis epithelium do not develop in the normal lungs transplanted into cystic fibrosis patients.

HEART-LUNG TRANSPLANTATIONIn someways the operation is technically simpler than heart transplantation, because after excision of the recipient heart and lungs the vascular anastomoses are confined to the right atrium (using a cuff of recipient atrium) and the aorta.However, the removal of the recipient lungs is often a tedious and difficult dissection because of dense and highly vascular adhesions which form in many types of lung pathology.In addition, the final anastomosis is between recipient and donor trachea, which has the greatest tendency to breakdown as a result of late ischaemia.To help heal the anastomosis, many surgeons mobilise a vascularized pedicle of tissue, either intercostal muscle or omentum from the abdomen, and wrap it around the suture line.One interesting variant of the heart-lung transplantation procedure has been to use the excised heart, which is relatively healthy in some patients, for eg-those patients with cystic fibrosis, for transplantation into another recipient in need of a heart alone- a so called 'domino' operation.

MANAGEMENT AFTER THORACIC ORGAN TRANSPLANTATIONThe immediate post-operative recovery after heart transplantation and/or lung transplantation is largely determined by the predonation status of the organs, provided prolonged cold ischaemia is avoided. Poor function equates with early mortality, unless a new donor can be found.Later problems arise from rejection, which is best diagnosed early using routine transjugular endomyocardial biopsies for the heart.Unfortunately the lungs are more prone to rejection (often in the absence of a rejection in a heart graft) and trans bronchial lung biopsies must be performed when rejection is suspected.In, both cases anti-rejection treatment must be judicious yet early, to avoid both severe rejection which may well be fatal or over immunosuppression which often ends in fatal respiratory infection.CMV infection is a particular problem afterlung transplantation and matching of CMV status is important to minimize the risks.In the long term, chronic rejection remains a problem for both heart and lung grafts, with the development of diffuse coronary artery narrowing termed 'accelerated graft atherosclerosis' and fibrosing bronchiolitis.Both these conditions may be forms of chronic rejection and recent evidence has suggested that mathcing of the grafts may alleviate these problems.Advances in predonation typing and organ preservation are being actively sought to allow increased opportunity for tissue type matching. |

| BACK TO TOP |

| NEXT PAGE.... |

|